Abstract

The NCCN Guidelines for Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) comprise a heterogeneous group of myeloid disorders with a highly variable disease course that depends largely on risk factors. Risk evaluation is therefore a critical component of decision-making in the treatment of MDS. The development of newer treatments and the refinement of current treatment modalities are designed to improve patient outcomes and reduce side effects. These NCCN Guidelines Insights focus on the recent updates to the guidelines, which include the incorporation of a revised prognostic scoring system, addition of molecular abnormalities associated with MDS, and refinement of treatment options involving a discussion of cost of care.

Overview

Refinements to the method of prognosis and stratification of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and to the treatment regimens are indicated by the revisions to the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Myelodysplastic Syndromes.1 Previously, the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) and WHO Prognostic Scoring System (WPSS), which are based on morphology, cytogenetics, and the presence of cytopenias in patients with MDS, were the most frequently used.2,3 Recently, in a joint multinational study, termed the IWG-PM project, the IPSS was revised (IPSS-R)4 and has shown improved prognostic capability. This has initiated a transition from earlier scoring systems to the IPSS-R.

Conventional karyotyping remains the keystone for diagnosis of MDS5,6; however, refined cytogenetic categories have been given greater weight in the IPSS-R,7 adding credence to the importance of developing diagnostic tests that determine genetic abnormalities. Additionally, these advances can aid in the design of future clinical trials.

The NCCN Guidelines are updated at least once per year, which is necessary to provide the most up-to-date treatments for clinical practice. One recent discussion regarding cancer treatment as a whole is the incorporation of risk/benefit and financial cost strategies. Although evaluation of the risks and benefits of individual treatments has always factored into patient care, a greater number of treatment protocols are now available across which clinicians must evaluate the advantage to patient outcome, possibility of adverse events, effect on quality of life, and degree of patient financial burden before determining the appropriate treatment. The financial impact of treating patients with MDS according to the NCCN Guidelines has been reported.8 The latest full version of these guidelines is available on the NCCN Web site (NCCN.org).

Universal Implementation of the IPSS-R

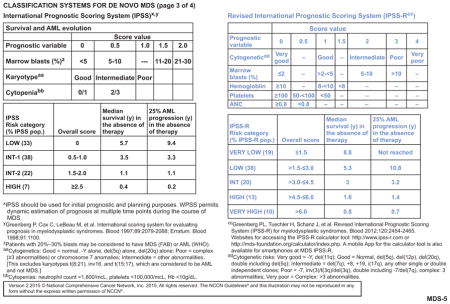

The IPSS-R was derived from analysis of a large dataset including 7012 patients from multiple international institutions. The IPSS-R defines 5 risk groups (very low, low, intermediate, high, and very high), versus the 4 groups in the IPSS, and provides more detailed cytogenetic abnormalities and subgroups (see MDS-5, page 263). Specifically, 16 cytogenetic abnormalities versus the previous 6 are identified, and the cytogenetic subgroups are refined to comprise 5 versus 3 risk groups.4,7 The newer classification separates the original designation of “marrow blasts <5%” into 2 subgroups, defined as “marrow blasts ≤2%” and “marrow blasts >2% to <5%.” Furthermore, the IPSS-R includes a depth of cytopenias measurement, defined with cutoffs for hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, and neutrophil counts. Age, performance status, serum ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase, and β2-microglobulin provide additional differentiating features related to survival but not for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) evolution. It should be noted that age is a more significant prognostic factor among lower-risk groups compared with higher-risk groups.4

Several retrospective studies have demonstrated the validity of the IPSS-R. In a database analysis of patients with MDS from a single institution (N=1088), median overall survival (OS) according to IPSS-R risk categories was 90 months for very low, 54 months for low, 34 months for intermediate, 21 months for high, and 13 months for very high (P<.005).9 The median follow-up in this study was 70 months. The IPSS-R was also predictive of survival outcomes among patients who received therapy with hypomethylating agents (n=618). A significant survival benefit with azacitidine was shown only for the high and very high IPSS-R risk groups compared with patients not receiving azacitidine (median survival, 25 vs 18 months; P<.028; median survival, 15 vs 9 months; P=.005, respectively). Significantly longer OS with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was only observed for patients at high risk (median survival, 40 vs 19 months without HSCT; P<.005) and very-high risk (median survival, 31 vs 12 months without HSCT; P<.005).9

Another multicenter study reviewed patients with MDS who received either best supportive care only (n=1314), induction chemotherapy (n=214), or allogeneic transplant (n=167) to compare the prognostic value of the IPSS-R with the IPSS, WPSS, and Duesseldorf score.10 The IPSS-R could clearly distinguish risk categories and was better than the 3 other scoring systems for identifying patient survival and risk of AML evolution. The distribution of patients among the IPSS-R groups was similar to that of the cohort in the original design of the IPSS-R. Overall, patients who had worse prognosis and were formerly categorized as lower risk by the IPSS could be identified as higher risk by the IPSS-R. Similarly, the IPSS-R ascribed to lower-risk category patients who had a more favorable prognosis than was predicted by the IPSS.10

As part of a larger study to identify predictive factors for patients receiving allogeneic HSCT, Della Porta et al11 evaluated the ability of the IPSS-R to predict relapse and lower OS after transplant in 519 patients with MDS or oligoblastic AML. In a multivariate model, the IPSS-R significantly affected OS (hazard ratio [HR], 1.41; P<.001) and the probability of relapse (HR, 1.81; P<.001). The IPSS-R also showed the ability to identify posttransplantation outcomes. The study used the Akaike criterion and determined that the IPSS-R was more indicative of prognosis than the IPSS, especially during early-stage disease.11 One of the known limitations of the IPSS was the poor stratification of posttransplant outcome in patients with early-stage disease.12 This study has shown improvement of the IPSS-R over the IPSS in risk-stratifying this group.11

Additional studies have confirmed the value of the IPSS-R in treated and untreated patients.9–11,13–18 Because more accurate risk stratification by the IPSS-R compared with the IPSS and WPSS has been demonstrated,16 the IPSS-R categorization is preferred. Although implementation of the IPSS-R has already occurred in many institutions, it has not fully transitioned into community practice, the drug approval process, or transplant decision applications. Community hospitals may find calculating the IPSS-R to be complex, particularly the inclusion of cytogenetic abnormalities; however, online calculators (http://advanced.ipss-r.com) and SmartPhone apps are available for the IPSS-R to facilitate its use. A difficulty in universally adopting the IPSS-R to the drug approval process is that it could influence how drugs are used if they were originally approved under the IPSS. Lastly, the complication with applying the IPSS-R to the decision algorithms in terms of when to recommend transplant was discussed. These algorithms are currently based on the IPSS or WPSS.19,20 Although institutions are predicted to switch over to the IPSS-R as more data become available, a paucity of data remains regarding transplant. Recently, data were presented on the potential utility of using the IPSS-R for decision analysis of stem cell transplantation.21 The IPSS-R is currently being evaluated in therapy-related MDS, and preliminary data suggest that with additional modifications, the IPSS-R may be applicable to this distinct population of patients with MDS.22 Taken together, the NCCN Panel decided that it was premature to eliminate other scoring systems from the algorithm; however, the IPSS-R should be substituted when possible because of its greater accuracy.

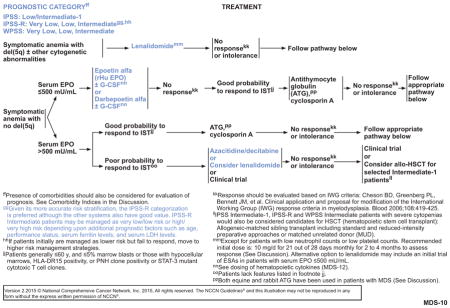

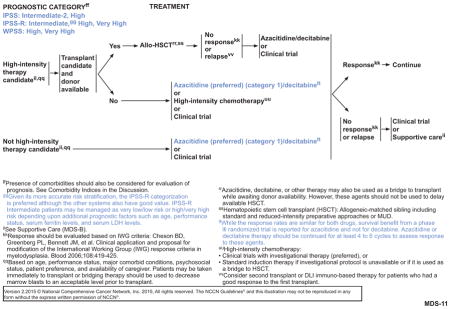

During this transition period, before more uniform prognostic risk stratification is accepted by the field, keeping multiple prognostic scoring systems in the algorithms seems prudent. Therefore, each algorithm page that refers to treatment pathways based on prognostic category indicates category designations for IPSS, IPSS-R, and WPSS (see MDS-10 and MDS-11, pages 265 and 266, respectively). The algorithms address certain recommendations in the footnotes. For cases in which a patient is managed as lower risk but fails to experience response, the recommendation is to then move to a higher-risk management strategy.

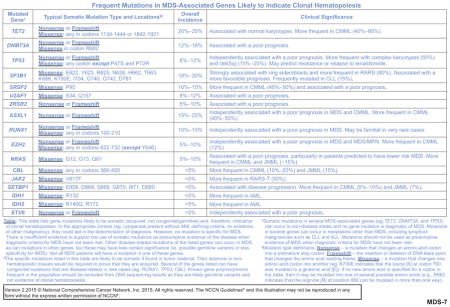

Appropriate Incorporation of Frequent Mutations in Patient Evaluation

In recent years, several gene mutations have been identified among patients with MDS that may, partly, contribute to the clinical heterogeneity of the disease course, and thereby influence prognosis. A large variety of gene mutations will be present in most patients with newly diagnosed MDS, including most patients with normal cytogenetics. The NCCN Panel does not recommend molecular testing to establish a diagnosis of MDS. Comparable abnormalities have been described in apparently normal individuals. Also, in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of MDS using standard diagnostic criteria only, a limited number of the abnormalities have established prognostic significance. Several studies examining large numbers of MDS marrow or peripheral blood samples have identified more than 40 recurrently mutated genes, with more than 80% of patients harboring at least 1 mutation.23–26 Frequent mutations in MDS-associated genes that are likely to be indicative of clonal hematopoiesis are listed in the NCCN Guidelines (see MDS-7, page 264). These genes can be categorized into several groups: (1) transcription factors (TP53, RUNX1, ETV6); (2) epigenetic regulators and chromatin-remodeling factors (TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1/2); (3) pre-mRNA splicing factors (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, ZRSR2); and (4) signaling molecules (NRAS, CBL, JAK2, SETBP1).

The most frequently mutated genes were TET2, SF3B1, ASXL1, DNMT3A, SRSF2, RUNX1, TP53, U2AF1, EZH2, ZRSR2, STAG2, CBL, and NRAS, although no single mutated gene was found in more than a third of patients. Several of these gene mutations are associated with adverse clinical features, such as complex karyotypes (TP53), excess bone marrow blast proportion (RUNX1, NRAS, and TP53), and severe thrombocytopenia (RUNX1, NRAS, and TP53). Despite associations with clinical features considered by prognostic scoring systems, mutations in several genes hold independent prognostic value. Mutations of TP53, EZH2, ETV6, RUNX1, and ASXL1 have been shown to predict decreased OS in multivariable models adjusted for IPSS or IPSS-R risk groups in several studies of distinct cohorts.23,26 Within IPSS risk groups, a mutation in 1 or more of these genes identifies patients whose survival risk resembles that of patients in the next highest IPSS risk group (eg, the survival curve for INT-1–risk patients with an adverse gene mutation was similar to that of patients assigned to the INT-2–risk group by the IPSS).23 When applied to patients stratified by the IPSS-R, the presence of a mutation in 1 or more of these 5 genes was associated with shorter OS for patients in the low- and intermediate-risk groups.26 Thus, the combined analysis of these gene mutations and the IPSS or IPSS-R may improve on the risk stratification provided by these prognostic models alone. Mutations of ASXL1 have also been shown to carry independent adverse prognostic significance in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.27,28 Other mutated genes have been associated with decreased OS, including DNMT3A, U2AF1, SRSF2, CBL, PRPF8, SETBP1, and KRAS.23,26,29–32 Mutations of SF3B1 have been associated with a more favorable prognosis, but this may not be an independent risk factor.26,33

Mutations of TP53 are strongly associated with complex and monosomal karyotypes. However, approximately 50% of patients with a complex karyotype have no detectable TP53 abnormality and have an OS comparable to that of patients with noncomplex karyotypes. Therefore, TP53 mutation status may be useful for refining the prognosis of these patients typically considered to have higher-risk disease.23,34 Patients with del(5q), either as an isolated abnormality or often as part of a complex karyotype, have a higher rate of concomitant TP53 mutations.35,36 These mutations are associated with diminished response or relapse after treatment with lenalidomide.37,38 In these cases, TP53 mutations may be secondary events and are often present in small subclones that can expand during treatment. More sensitive techniques may be required to identify the presence of subclonal, low-abundance TP53 mutations before treatment.

Although several recurring genetic mutations have been identified in studies of patients with MDS and may be useful for assessing prognosis, their possible utility in diagnosing MDS has not been established. Some mutations may prove useful after further analysis, but many of the same mutations have been identified in elderly patients who do not have MDS,39 and thus their use for diagnosis is not currently recommended.

As noted in the algorithms, for patients categorized as intermediate risk by the IPSS-R, prognostic factors may affect treatment. This may be seen in patients who are initially treated on a lower-risk scale but do not experience a response to treatment. The presence of these mutations may direct the clinician to a higher-risk treatment strategy (see MDS-10, page 265). Other patients who may benefit from mutational analysis are those who experience no response to hypomethylating agents and move to a clinical trial. These tests may be useful in determining an appropriate clinical trial that targets the specific lesion.

Significant discussion occurred regarding how to appropriately include mutations into the NCCN Guidelines. Although mutational analysis is not recommended for use in routine clinical circumstances, additional testing could be useful in some clinical situations, as described earlier. For these circumstances in which the identification of mutations would be clinically beneficial, the panel recommends the use of sites established for molecular analysis.

Cost-Effective Care

Patients with MDS require evaluation for short-term and long-term disease-related and treatment-related side effects, with continuous monitoring for disease progression or the development of complications, such as infections. Several therapeutic options are available for patients with MDS, depending on their specific clinical features as outlined in the NCCN Guidelines. The NCCN Guidelines for MDS should be consulted regarding criteria for treatment selection. However, occasionally clinicians must choose among these options based on individual patient factors. In these situations, it may also be appropriate to be aware of and consider cost-effective care. Optimization of treatment may often result in a concurrent reduction in cost.

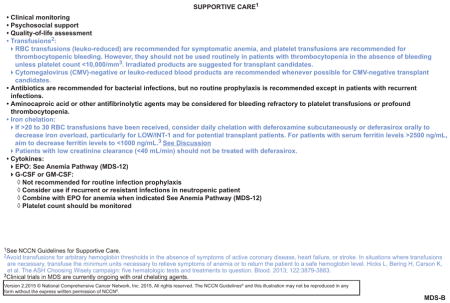

One treatment that has received more recent analysis is the evaluation of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion practices in patients who develop symptomatic anemia. The recommendation to keep transfusions to the minimal amount of units necessary to relieve symptoms or restore normal hemoglobin levels was highlighted in an article from the ASH Choosing Wisely Campaign.40 Similar verbiage has been added to the 2015 NCCN Guidelines for MDS (see MDS-B, page 267).41–43 Furthermore, there are inherent risks associated with transfusions, including transfusion-related reactions, transfusion-associated circulatory overload, bacterial contamination and viral infections, and iron overload. Iron overload is a particular concern for patients with MDS who receive frequent transfusions over several years. In these patients, iron overload may occur, causing an excess of iron deposition in the liver, heart, skin, and endocrine organs, resulting in potential complications and the need to consider iron chelation medications to prevent or stabilize such adverse events (see MDS-B, page 267).

The standard method to attempt to decrease RBC transfusions in symptomatic anemic patients with MDS without del(5q) is the use of recombinant erythropoietin.1 Dosing and response prediction (ie, relatively low serum recombinant erythropoietin, clinical risk status) are important considerations for use of this drug. The cost-effectiveness can also be evaluated among hematopoietic cytokines, specifically epoetin alpha (EPO) and darbepoetin for the treatment of symptomatic anemia. Based on the 2009 NCCN Guidelines for MDS, the annual cost of EPO ranged from $26,076 to $52,176 compared with the cost of darbepoetin, which ranged from $41,904 to $87,300.8 The variability in cost reflects the spectrum of acceptable dosages. However, further studies have compared lower doses of darbepoetin with EPO and have shown that 200 mcg of darbepoetin every 2 weeks has equivalent effectiveness as 40,000 U of EPO.44,45 Using these values instead of a range, the cost of EPO would be approximately $18,824 compared with the cost of darbepoetin, which is estimated to be $15,132. Therefore, dosage is a significant consideration when comparing the cost. Furthermore, darbepoetin can be administered less frequently than EPO, providing a significant value in terms of quality of life. Because both of these drugs may be coadministered with a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, the cost of the additional cytokine does not ultimately affect the comparison of these hematopoietic cytokines.

Another option for reducing RBC transfusions in patients with MDS is the use of lenalidomide. The FDA has approved lenalidomide for the treatment of transfusion-dependent anemia in patients with del(5q) classified as having low- or INT-1–risk MDS (see MDS-10, page 265). Clinical trial data have shown that lenalidomide treatment can result in transfusion independence in a substantial proportion of these patients (≈60%–70%).46,47 Studies have shown the relative safety of lenalidomide in these patients and improved quality of life outcomes in randomized clinical trials.48,49 Thus, lower-risk patients with del(5q) chromosomal abnormalities and symptomatic anemia should receive lenalidomide. However, lenalidomide should be avoided in those with a clinically significant decrease in neutrophil or platelet counts.50

Although the cost of lenalidomide is higher than other treatment regimens, the expense is partially offset by the reduction in the number of transfusions and the duration of transfusion independence. The estimated annual cost for lenalidomide when given 21 days per month is $66,204, based on the 2009 NCCN Guidelines.8 A publication evaluating the cost-effectiveness of lenalidomide versus best supportive care from Goss et al51 also showed a similar cost for lenalidomide of $63,385. In this study, the cost of best supportive care was approximately $54,940 annually. Factors that were included in the overall cost were the annual primary cost of the intervention, annual cost of transfusions when on the intervention, and annual cost of drug-related complications. Additionally, comparison for health outcomes showed that 67.0% of patients given lenalidomide were transfusion-free versus only 8.9% of patients receiving best supportive care. Although not quantifiable from a financial benefit, quality of life is generally greater with lenalidomide treatment because of a fewer number of treatments and the oral bioavailability of lenalidomide.

Another treatment cost associated with RBC transfusion includes the use of iron chelation drugs. The NCCN MDS Panel recommends consideration of deferoxamine subcutaneously for 5 to 7 days per week or daily deferasirox orally to decrease iron overload (aiming for a target ferritin level <1000 ng/mL) in the following IPSS low- or INT-1–risk patients: (1) those who have received or are anticipated to receive more than 20 RBC transfusions, particularly for lower-risk patients; (2) those for whom ongoing RBC transfusions are anticipated; and (3) those with serum ferritin levels greater than 2500 ng/mL (see MDS-B, page 267). Although both iron chelators are a category 2A recommendation, choosing between the 2 options may involve several factors. The prescribing information for deferasirox contains a black box warning pertaining to the increased risks for renal or hepatic impairment/failure and gastrointestinal bleeding in certain patients.52 It is recommended that patients on deferasirox therapy be closely monitored via measurement of serum creatinine and/or creatinine clearance and liver function tests before initiation of therapy, and regularly thereafter. The oral availability of this formulation makes it easier to administer than deferoxamine for most patients in terms of patient compliance. The subcutaneous administration of deferoxamine is more time-intensive and entails indirect costs associated with administration of the drug. The direct cost of deferasirox annually was estimated to be $46,008 per year compared with deferoxamine, which was estimated at $21,048 per year.8 However, although deferasirox has a higher direct cost, the associated indirect costs must be evaluated to determine overall financial burden. In a study from the United Kingdom, deferasirox was evaluated to be more cost-effective than deferoxamine in patients with lower-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS based on the cost of the drug, cost of administration and monitoring, and quality-of-life outcomes, with the last serving as the key driver for improved quality-adjusted life-years.53 Taken together, both iron chelators have advantages and disadvantages that must be considered for each patient before a treatment is determined.

Another treatment option that has been evaluated for cost-effectiveness involves the use of hypomethylating agents. Currently, azacitidine and decitabine are considered to be therapeutically similar, although the improved survival of higher-risk patients treated with azacitidine compared with control patients in a phase III trial supports the preferred use of azacitidine in this setting (see MDS-10 and MDS-11, pages 265 and 266, respectively).54–57 Azacitidine can be administered subcutaneously or intravenously compared with decitabine, which requires an intravenous infusion with clinic or hospital admission. Studies have shown that indirect costs for decitabine are higher (if the azacitidine is given subcutaneously), further adding to the expense.58 Indirect costs were calculated to include hospitalization, management of side effects, physician visits, and use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.58 Selection of the hypomethylating agent azacitidine may result in a lower expense but equivalent benefit if azacitidine is given subcutaneously.8,58

Comparison between cancer treatments must evaluate whether any one treatment confers a benefit in survival or quality of life compared with another. If a benefit is observed, it should be weighed against the treatment cost. As discussed earlier, this does not necessarily mean a patient will be accepting a poorer prognosis or less valuable treatment. Historically, the NCCN Guidelines have excluded cost of a treatment from their deliberations on recommendations in order to provide an unbiased set of treatment options. However, this means that options in the current guidelines that are considered equivalent based on patient outcomes may not be equivalent when cost is a factor. Future iterations of the guidelines may involve cost evaluation, but until then, clinicians should be advised to consider cost, not in exchange for reduced care, but rather to prevent any undue financial burden to the patient.

Conclusions

The yearly revision of the NCCN Guidelines is a reflection of the rate at which cancer research advances treatment. However, the advances must be conveyed to clinicians and patients to allow integration into practice, and to enable patients to advocate regarding their own care. The most recent update has highlighted advances in the prognostic and diagnostic aspects of MDS. Treatment options have also been updated and modified to provide improved patient care. Future directions must endeavor to address the increasing cost of care. With the current state of health care, strategies to improve clinical treatment should also incorporate economic strategies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by an educational grant from Eisai; a contribution from Exelixis Inc.; educational grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech BioOncology, Merck, Novartis Oncology, Novocure; and by an independent educational grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Footnotes

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment.

The NCCN Guidelines® Insights highlight important changes to the NCCN Guidelines® recommendations from previous versions. Colored markings in the algorithm show changes and the discussion aims to further the understanding of these changes by summarizing salient portions of the NCCN Guideline Panel discussion, including the literature reviewed.

These NCCN Guidelines Insights do not represent the full NCCN Guidelines; further, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding the content, use, or application of the NCCN Guidelines and NCCN Guidelines Insights and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way.

The full and most current version of these NCCN Guidelines are available at NCCN.org.

© National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2015, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate. Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Individuals Who Provided Content Development and/or Authorship Assistance:

Peter L. Greenberg, MD, Panel Chair, has disclosed the following relationships with commercial interests: grant/research support from GlaxoSmithKline, KaloBios, Inc., and Onconova Therapeutics, Inc., and scientific advisor for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Rafael Bejar, MD, PhD, Panel Member, has disclosed that is a consultant for Celgene Corporation and Genoptix. He also holds intellectual property rights from Genoptix.

Dorothy A. Shead, MS, Director, Patient & Clinical Information Operations, NCCN, has disclosed that she has no relevant financial relationships.

Courtney Smith, PhD, Oncology Scientist/Medical Writer, NCCN, has disclosed that she has no relevant financial relationships.

References

- 1.Greenberg PL, Stone RM, Bejar R, et al. [Accessed February 6, 2015];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Myelodysplastic Syndromes, Version 2.2015. Available at: NCCN.org.

- 2.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. Erratum in Blood 1998;2091:1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malcovati L, Germing U, Kuendgen A, et al. Time-dependent prognostic scoring system for predicting survival and leukemic evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3503–3510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R) for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:2454–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Wang XQ, Xu XP, Lin GW. Cytogenetic evolution correlates with poor prognosis in myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Souza Fernandez T, Ornellas MH, Otero de Carvalho L, et al. Chromosomal alterations associated with evolution from myelodysplastic syndrome to acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2000;24:839–848. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(00)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schanz J, Tuchler H, Sole F, et al. New comprehensive cytogenetic scoring system for primary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia after MDS derived from an international database merge. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:820–829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg PL, Cosler LE, Ferro SA, Lyman GH. The costs of drugs used to treat myelodysplastic syndromes following National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:942–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra A, Corrales-Yepez M, Ali NA, et al. Validation of the revised International Prognostic Scoring System in treated patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:566–570. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neukirchen J, Lauseker M, Blum S, et al. Validation of the revised international prognostic scoring system (IPSS-R) in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: a multicenter study. Leuk Res. 2014;38:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Della Porta MG, Alessandrino EP, Bacigalupo A, et al. Predictive factors for the outcome of allogeneic transplantation in patients with MDS stratified according to the revised IPSS-R. Blood. 2014;123:2333–2342. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-542720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alessandrino EP, Della Porta MG, Bacigalupo A, et al. WHO classification and WPSS predict posttransplantation outcome in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: a study from the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) Blood. 2008;112:895–902. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ades L, Lamarque M, Raynaud S, et al. Revised-IPSS (IPSS-R) is a powerful tool to evaluate the outcome of mds patient treated with azacitidine (AZA): the Groupe Francophone Des Myelodysplasies (GFM) experience [abstract] Blood. 2012;120:Abstract 422. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-453555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cermak J, Mikulenkova D, Brezinova J, Michalova K. A reclassification of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) patients of RAEB-1 subgroup according to IPSS-R improves discrimination of high risk patients and better predicts overall survival. A retrospective analysis of 49 patients [abstract] Blood. 2012;120:Abstract 4957. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messa E, Gioia D, Evangelista A, et al. High predictive value of the revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R): an external analysis of 646 patients from a multiregional Italian MDS registry [abstract] Blood. 2012;120:Abstract 1702. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voso MT, Fenu S, Latagliata R, et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) predicts survival and leukemic evolution of myelodysplastic syndromes significantly better than IPSS and WHO Prognostic Scoring System: validation by the Gruppo Romano Mielodisplasie Italian Regional Database. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2671–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valcarcel D, Sanz G, Ortega M, et al. Identification of poor risk patients in low and intermediate-1 (Int-1) IPSS MDS with the new IPSS-R index and comparison with other prognostic indexes. A study by the Spanish Group of MDS (GESMD) [abstract] Blood. 2012;120:Abstract 702. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warlick ED, Hirsch BA, Nguyen PL, et al. Comparison of IPSS and IPSS-R scoring in a population based myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) study [abstract] Blood. 2012;120:Abstract 3841. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malcovati L, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Bowen D, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary myelodysplastic syndromes in adults: recommendations from the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2013;122:2943–2964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-492884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroger N. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for elderly patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2012;119:5632–5639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-380162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.della Porta MG, Alessandrino EP, Jackson CH, et al. Decision analysis of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome stratified according to the revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R) [abstract] Blood. 2014;124:Abstract 531. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ok CY, Hasserjian RP, Fox PS, et al. Application of the international prognostic scoring system-revised in therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:185–189. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bejar R, Stevenson KE, Caughey BA, et al. Validation of a prognostic model and the impact of mutations in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3376–3382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Malcovati L, et al. Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2013;122:3616–3627. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-518886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28:241–247. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itzykson R, Kosmider O, Renneville A, et al. Prognostic score including gene mutations in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2428–2436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patnaik MM, Itzykson R, Lasho TL, et al. ASXL1 and SETBP1 mutations and their prognostic contribution in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a two-center study of 466 patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:2206–2212. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter MJ, Ding L, Shen D, et al. Recurrent DNMT3A mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2011;25:1153–1158. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graubert TA, Shen D, Ding L, et al. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:53–57. doi: 10.1038/ng.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thol F, Kade S, Schlarmann C, et al. Frequency and prognostic impact of mutations in SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;119:3578–3584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-399337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makishima H, Yoshida K, Nguyen N, et al. Somatic SETBP1 mutations in myeloid malignancies. Nat Genet. 2013;45:942–946. doi: 10.1038/ng.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Hodnefield JM, et al. SF3B1 mutations are prevalent in myelodysplastic syndromes with ring sideroblasts but do not hold independent prognostic value. Blood. 2012;119:569–572. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bejar R, Papaemmanuil E, Haferlach T, et al. TP53 mutation status divides MDS patients with complex karyotypes into distinct prognostic risk groups: analysis of combined datasets from the International Working Group for MDS-Molecular Prognosis Committee [abstract] Blood. 2014;124:Abstract 532. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebaa A, Ades L, Baran-Marzack F, et al. Incidence of 17p deletions and TP53 mutation in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia with 5q deletion. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:1086–1092. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jadersten M, Saft L, Smith A, et al. TP53 mutations in low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q) predict disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1971–1979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallo M, Del Rey M, Ibanez M, et al. Response to lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q): influence of cytogenetics and mutations. Br J Haematol. 2013;162:74–86. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jadersten M, Saft L, Pellagatti A, et al. Clonal heterogeneity in the 5q-syndrome: p53 expressing progenitors prevail during lenalidomide treatment and expand at disease progression. Haematologica. 2009;94:1762–1766. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Blood. 2013;122:3879–3883. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-518423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Napolitano LM, Kurek S, Luchette FA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care. J Trauma. 2009;67:1439–1442. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ba7074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Retter A, Wyncoll D, Pearse R, et al. Guidelines on the management of anaemia and red cell transfusion in adult critically ill patients. Br J Haematol. 2013;160:445–464. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patton J, Reeves T, Wallace J. Effectiveness of darbepoetin alfa versus epoetin alfa in patients with chemotherapy-induced anemia treated in clinical practice. Oncologist. 2004;9:451–458. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-4-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patton JF, Sullivan T, Mun Y, et al. A retrospective cohort study to assess the impact of therapeutic substitution of darbepoetin alfa for epoetin alfa in anemic patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Support Oncol. 2005;3:419–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.List AF. Emerging data on IMiDs in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Semin Oncol. 2005;32:S31–35. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1456–1465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Revicki DA, Brandenburg NA, Muus P, et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes of lenalidomide in transfusion-dependent patients with low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with a chromosome 5q deletion: results from a randomized clinical trial. Leuk Res. 2013;37:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliva EN, Latagliata R, Lagana C, et al. Lenalidomide in International Prognostic Scoring System low and intermediate-1 risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q): an Italian phase II trial of health-related quality of life, safety and efficacy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2458–2465. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.778406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giagounidis A, Mufti GJ, Mittelman M, et al. Outcomes in RBC transfusion-dependent patients with low-/intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with isolated deletion 5q treated with lenalidomide: a subset analysis from the MDS-004 study. Eur J Haematol. 2014;93:429–438. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goss TF, Szende A, Schaefer C, et al. Cost effectiveness of lenalidomide in the treatment of transfusion-dependent myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States. Cancer Control. 2006;13(Suppl):17–25. doi: 10.1177/107327480601304s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Exjade [prescribing information] Stein, Switzerland: Novartis Pharma Stein AG; 2013. [Accessed January 23, 2015]. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021882s019lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tolley K, Oliver N, Miranda E, et al. Cost effectiveness of deferasirox compared to desferrioxamine in the treatment of iron overload in lower-risk, transfusion-dependent myelodysplastic syndrome patients. J Med Econ. 2010;13:559–570. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.516203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silverman LR, McKenzie DR, Peterson BL, et al. Further analysis of trials with azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: studies 8421, 8921, and 9221 by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3895–3903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:52–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kogan AJ, Dunn JD. Myelodysplastic syndromes: health care management considerations. Manag Care. 2009;18:25–28. discussion 28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]