Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) of unknown primary site (UP) account for approximately 4% of HNSCCs.1 These cases have historically been subclinical tumors arising from the nasopharynx, hypopharynx, or oropharynx. In the era of human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive HNSCCs, the presence of HPV in cervical malignancy of UP has been strongly associated with oropharyngeal primary tumors.2 Tumors that are HPV–positive are typically small and arise from cryptic lingual and palatine lymphoid tissues, rendering primary tumor detection challenging.3 The traditional diagnostic paradigm for finding the primary tumor consists of a physical examination, fiber-optic laryngoscopy, and imaging. If these techniques are unsuccessful, operative examination under anesthesia is warranted, including direct laryngoscopy with “blind” biopsies directed at the nasopharynx, hypopharynx, oropharynx, larynx, and palatine and lingual tonsillectomy. Failure to identify the primary tumor site subsequently necessitates radiation of Waldeyer’s ring and concurrent chemotherapy. This report shows that transcervical ultrasound (US) can be used to localize oropharyngeal tumors. The study was reviewed and approved by the Greater Baltimore Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Case Report

A 60-year-old white man, a former smoker and occasional drinker, presented with a 1-month history of enlarging left neck mass. By report, there was no evidence of a primary site clinically. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the neck mass revealed nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Examination under anesthesia with direct laryngoscopy with biopsies of the base of tongue (BOT), nasopharynx, and bilateral palatine tonsillectomies failed to reveal the primary site.

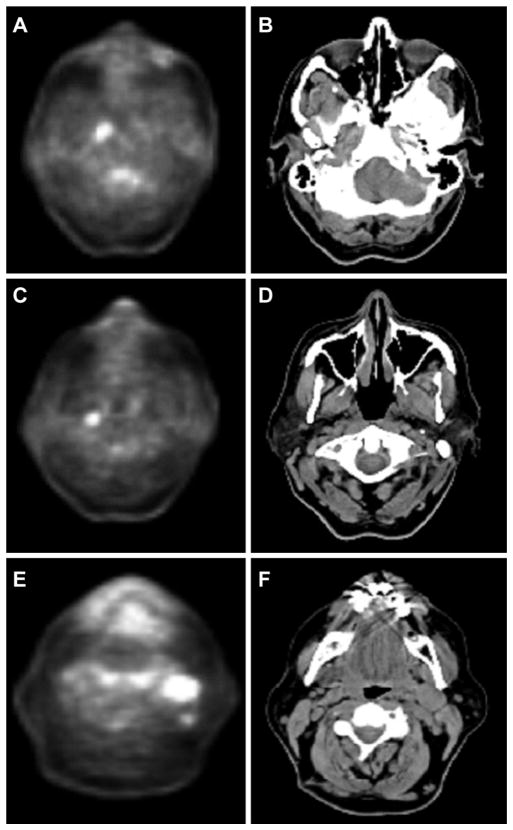

The patient presented to our clinic for secondary evaluation with a 2-cm left level II cervical lymph node. There was no evidence of a primary tumor on physical or fiber-optic examinations. Review of the FNA confirmed the cytologic diagnosis of p16-positive squamous cell carcinoma. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/ CT) revealed small foci of uptake without CT abnormality in the right nasopharynx (standardized uptake value [SUV] 5.6) and retropharynx (SUV 4.3) and 2 enlarged left level II lymph nodes measuring 1.7 × 2.3 cm and 1.2 × 0.7 cm with SUVs of 7.5 and 4.1, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) findings. Hypermetabolic focus in the right nasopharynx (A) and hypopharynx (C). (B, D) CT without corresponding abnormalities. (E, F) Enlarged cervical nodes in left level II.

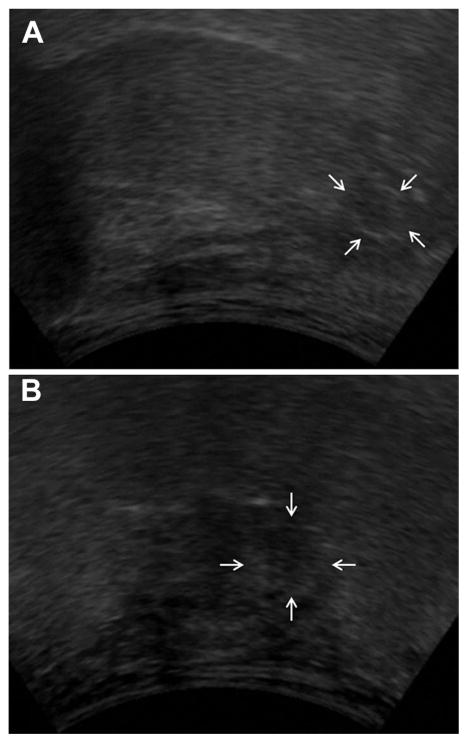

A transcervical US was performed, demonstrating a hypoechoic heterogeneous lesion deep in the left BOT approaching the vallecula (Figure 2). The 1.2-cm (superior-inferior), 1.2-cm (anterior-posterior), and 1.3-cm (medial-lateral) mass was ill defined and purely endophytic. On parasagittal view, the lesion appeared to be approximately 9.2 mm from the mucosal surface of the BOT apex and 3.5 mm from the mucosal surface of the vallecula.

Figure 2.

Transcervical ultrasound of the tongue base. A slightly hypoechoic heterogeneous lesion was found within the deep tongue base. (A) Coronal view (30° from hyoid, B).

Direct laryngoscopy was again inconclusive. Directed deep biopsies based on the preoperative US revealed at least squamous cell carcinoma in situ. The patient was treated with cisplatin, concurrent with standard fractionation external beam radiation. Posttreatment PET/CT revealed no evidence of disease, and the patient is free of disease at 2 years.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the successful application of preoperative transcervical US to visualize a BOT malignancy and to help direct biopsies in a patient who would otherwise have been treated as having HNSCC of UP. Ultrasonography is low risk, inexpensive, and repeatable, and it can be performed easily in an office setting. Alternative approaches for this patient would be to perform lingual tonsillectomy for diagnostic purposes or to treat the entire pharyngeal axis with radiation for UP.1 Lingual tonsillectomy has inherent risks of anesthesia, bleeding, dysphagia, pain, and delay in definitive radiotherapy. In this case, it is also possible that a lingual tonsillectomy may not have detected this deep-seated tumor. The UP tumor treatment includes the entire pharyngeal axis and unnecessarily exposes the constrictor muscles and mucosa to radiation, thereby increasing the risk of acute and chronic side effects while also underdosing a potentially targetable and curable cancer.

In this case, US enabled identification of the primary lesion when PET/CT failed to reveal any abnormality in the oropharynx. Similarly, there was no asymmetry or mass on CT. Instead, the US revealed a small endophytic lesion deep in the tongue base without any clinically appreciable overlying mucosal changes or palpable abnormality. Indeed, this BOT lesion was identified despite previously performed blind biopsies. Ultrasound-guided transcervical FNA biopsy of the tongue base is feasible,4 and the use of US to search for the primary site of UP HNSCC has been previously reported.5 Oropharyngeal US may have utility in the evaluation of UP and oropharyngeal HNSCCs, but further investigation is necessary.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Wojciech K. Mydlarz, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, revising, final approval; Jia Liu, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, final approval; Ray Blanco, data analysis, manuscript revision, final approval; Carole Fakhry, acquisition, analysis, manuscript conception, design, drafting, revising, final approval.

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: None.

References

- 1.Strojan P, Ferlito A, Medina JE, et al. Contemporary management of lymph node metastases from an unknown primary to the neck: I. A review of diagnostic approaches. Head Neck. 2013;35:123–132. doi: 10.1002/hed.21898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillison ML, D’Souza G, Westra W, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–420. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meacham RK, Boughter JD, Jr, Sebelik ME. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the tongue base: a cadaver feasibility study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:864–869. doi: 10.1177/0194599812446677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fakhry C, Agrawal N, Califano J, et al. The use of ultrasound in the search for the primary site of unknown primary head and neck squamous cell cancers. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]