Abstract

Despite the plethora of weight loss programs available in the US, the prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) among US adults continues to rise at least, in part, due to the high probability of weight regain following weight loss. Thus, the development and evaluation of novel interventions designed to improve weight maintenance is clearly needed. Virtual reality environments offer a promising platform for delivering weight maintenance interventions as they provide rapid feedback, learner experimentation, real-time personalized task selection and exploration. Utilizing virtual reality during weight maintenance allows individuals to engage in repeated experiential learning, practice skills, and participate in real-life scenarios without reallife repercussions, which may diminish weight regain. We will conduct an 18-month effectiveness trial (6 months weight loss, 12 months weight maintenance) in 202 overweight/obese adults (BMI 25–44.9 kg/m2). Participants who achieve ≥ 5% weight loss following a 6 month weight loss intervention delivered by phone conference call will be randomized to weight maintenance interventions delivered by conference call or conducted in a virtual environment (Second Life®). The primary aim of the study is to compare weight change during maintenance between the phone conference call and virtual groups. Secondarily, potential mediators of weight change including energy and macronutrient intake, physical activity, consumption of fruits and vegetables, self-efficacy for both physical activity and diet, and attendance and completion of experiential learning assignments will also be assessed.

Keywords: Virtual reality, Second Life, Weight loss, Weight maintenance, Conference call, Portion Controlled Meals

INTRODUCTION*

Numerous combinations of energy restriction and exercise have shown moderate short-term success in producing clinically significant (≥5%) [1] weight loss [2–4]. However, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among US adults continues at approximately 74.5% [5], due in part to the inability of individuals who lose weight to maintain weight loss. In general, 50% of individuals who initially lose weight will regain more than 45–75% of the weight lost within 12 to 30 months following treatment [2, 6–10]. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Survey indicated that only 17% of US adults who have ever been overweight have maintained weight loss long-term (i.e. losing 10% of body weight and maintaining that weight for at least 1 yr). [11]. Thus, there is a critical need to explore novel interventions designed to improve weight maintenance.

Current clinical guidelines recommend behaviorally based programs, which include energy restriction and physical activity to produce clinically relevant weight loss of 5% or more of total body weight (≥ 5%) [2–4, 12]. However, the delivery of traditional in-person behavioral weight management programs is labor intensive and presents numerous burdens for participants including scheduling/logistics, time and cost required to travel to and from a program site, childcare costs, etc. [13–15]. Thus, strategies such as the use of telephone or computer-based programs, may offer an attractive alternative for many individuals seeking weight management.

We have previously demonstrated significant and equivalent 6-month weight loss (~ 13%) between identical group behavioral weight loss interventions delivered in the traditional in-person clinic format or by phone conference call. However, during weight maintenance (12 months) both groups regained ~40% of the lost weight [16, 17]. We have also developed a weight management program delivered in Second Life (Second Life® (SL), Linden Labs, San Francisco, CA) [18], a popular, free, web-based virtual reality environment, where participants create virtual representations of themselves called “avatars” which can interact with other avatars in the virtual world. Although used by numerous government agencies (e.g. NASA, CDC) and industry (e.g. IBM, Dell, Nissan) for education and training [19, 20], research on the use of SL for health behavior change is in its infancy [20–22].

The potential for improved weight maintenance using virtual reality environments, such as SL, is well supported by education and behavior change theory [23]. A weight maintenance program delivered in SL allows participants to engage in repeated experiential learning with real-time informative feedback, practice skills, and participate in real-life scenarios without real-life consequences [24]. We demonstrated the potential of our SL intervention in a 9 month pilot trial that compared weight loss (3 months) and weight maintenance (6 months) between groups randomly assigned to weight loss by in-person clinic and maintenance using SL, or SL for both weight loss and maintenance [18]. Results indicated similar weight loss in both groups (~10%); however, during weight maintenance, the in-person clinic/SL group regained 13.6% of lost weight while the SL/SL group lost an additional 3.7%. Therefore, to further evaluate the effectiveness of SL for weight maintenance, we will conduct an 18-month trial in overweight/obese adults. Participants losing ≥ 5% of baseline weight in response to a 6 month behavioral weight loss program, delivered by phone conference call, will be randomly assigned to a 12 month weight maintenance intervention delivered either by conference call or in SL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

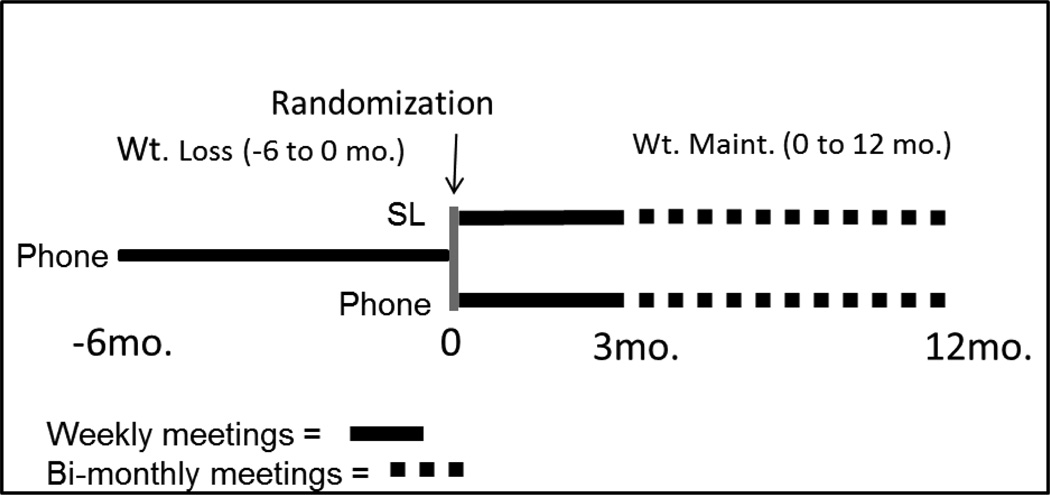

Study design (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Study Design

This study will be conducted between October 2013 and August 2016. This 18 month trial will consist of 2 phases; weight loss (−6 to 0 months) and weight maintenance (0 to 12 months). The weight loss intervention will include weekly behavioral sessions delivered by phone conference call. During weight maintenance both phone and SL sessions will be conducted weekly during the first 3 months, and twice per month during the final 9 months. All behavioral sessions will be ~ 60 minutes in duration. Our primary aim is to compare between group differences in weight change during weight maintenance. Secondarily we will assess potential mediators of weight change and conduct a qualitative and quantitative process analysis to monitor quality control, determine if the interventions were delivered as intended, assess challenges and barriers to intervention compliance, participant satisfaction, and potential competing factors that may have contaminated or diminished the effectiveness of the intervention. Trial outcomes will be assessed prior to weight loss (−6 months), following weight loss (0 months), at the mid-point (6 months) and following weight maintenance (12 months).

Recruitment goals and procedures

To provide adequate statistical power to evaluate our primary aim we will recruit 202 overweight/obese adults, at least 50% female and 20% minorities, who will be compensated for their participation. Potential participants will be recruited from Lawrence, Kansas and the Kansas City metropolitan area via newspaper advertisements, flyers, broadcast emails, word-of-mouth, and from the waiting list for our on-going weight management clinic. Interested individuals will be asked to complete a brief web-based initial eligibility screener that solicits information on height and weight, chronic diseases, medications, current physical activity (PA) levels and recent weight fluctuations. Individuals meeting the screening criteria will be invited to an orientation session where the study will be further explained, additional eligibility screeners will be completed, final eligibility will be assessed, and informed consent will be obtained. Approval for this trial has been obtained from the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center-Kansas City.

Participant eligibility

Primary care physician clearance will be required for all participants. To improve generalizability, individuals receiving treatment for prevalent chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, or with risk factors such as hypertension, tobacco use, lipid abnormalities etc. will be allowed to participate with physician approval. Inclusion criteria: 1) Body mass index (BMI) of 25.0 to 44.9 kg/m2. BMI range was restricted because individuals with a BMI < 25 kg/m2 are not classified as overweight and individuals with a BMI ≥ 45 kg/m2 require more aggressive weight loss interventions than we propose (e.g. surgery, medications, etc.). 2) Age 21 to 65 years. This age group represents individuals that are generally in the work force and likely to seek structured weight management and those who are the users of SL [25]. The lower age limit (21 yrs.) eliminates children and teens, who require different behavioral approaches for weight management. 3) Access to a computer with internet availability capable of running the SL program. 4) Ability to speak and read English. Exclusion criteria: 1) Serious medical risk such as type 1 diabetes, active cancer, recent cardiac event (i.e. heart attack, angioplasty, etc.) as determined by healthy history questionnaire and physician consent form. 2) Current treatment for psychological problems, or taking psychotropic medications. In our experience, individuals meeting these criteria typically are problematic due to time conflicts with other treatments and medications which induce weight change. Addressing psychological problems is beyond the scope of this study. 3) Eating disorders as determined by a score of ≥20 on the Eating Attitudes Test [26]. These individuals require counseling which is outside the scope of this study. 4) Adherence to specialized diet regimes i.e., multiple food allergies, vegetarian, macrobiotic, etc. 5) Pregnant during the previous 6 months, lactating, or planned pregnancy in the following 18 months. 6) Participation in a research project involving weight loss or exercise in the previous 6 months. 7) Participation in a regular exercise program (i.e., >500 kcal/week of planned activity) as estimated by questionnaire [27]). 8) Weight fluctuations > ± 2.27 kg over the 3 months prior to intake. 9) Inability to shop for groceries and prepare meals (e.g., military, college students with cafeteria meal plans, etc.). 10) Unwilling to be randomized to phone or SL groups following weight loss.

Randomization

Our primary aim is to compare weight change during weight maintenance between identical interventions delivered by conference call or in SL. Therefore, only participants who achieved ≥ 5% weight loss will be eligible to continue the weight maintenance phase. Based on our previous weight loss trials, we expect that 97%–99% of participants will meet the 5% criteria and ~70% will achieve >10% weight loss at 6 months [28–30]. Our randomization procedure was designed to preserve behavioral meeting days and times across the 18-month trial, which in our experience is an important consideration for minimizing participant attrition. At baseline, participants will be asked to agree to attend behavioral sessions at either 5:30 or 7:00 PM on a specific day of the week over 18 months. Participants will be stratified by sex and randomized by the trial statistician, in a 1:1 allocation, to either 5:30 or 7:00 time slots which will be associated with either the phone or SL groups. Results of the randomization will not be revealed to participants or health educators until completion of the weight loss phase (6 months). Investigators and data collection staff will remain blinded to the study condition across the 18 month intervention.

Intervention-Conceptual framework

Similar to many current weight management programs, the interventions will be grounded in social cognitive theory, problem-solving theory, and the relapse prevention model [31–35]. Key elements, incorporated in both the phone and SL interventions, include goal-setting, self-monitoring, direct reinforcement, interaction with health educators, and social support.

Standardized protocols

Our primary aim is to compare differences in weight change during weight maintenance between interventions delivered either by phone conference call or in SL. Therefore, the diets and PA protocols, behavioral lesson topics, experiential learning assignments and attention, i.e. meeting and assessment schedules, and meeting duration (60 min), will be identical for both groups. Participants will receive a notebook, which will include descriptions of the diet and PA protocols, recipes, meeting schedule, outlines, handouts related to diet and physical activity, worksheets and assignments for behavioral lessons, as well as health educator contact information.

Diet-Weight loss (−6 to 0 months)

Energy intake will be reduced to ~1,200 to 1,500 kcal/day using a combination of commercially available portion controlled meals (PCMs; HMR Weight Management Services Corp., Boston MA), fruits and vegetables (F/V), and non-caloric beverages. Participants will consume a minimum daily total of 3 shakes at ~100 kcal each, 2 entrées between 200 and 270 kcal each, and at least 5 one-cup servings of F/V. Non-caloric beverages such as diet soda, coffee, etc. will be allowed ad libitum. The use of PCMs reduces the energy and fat content of meals, provides participants with information regarding appropriate portion sizes, and standardizes weight loss, which reduces bias for subsequent comparison of the two delivery systems (phone vs. SL) for weight maintenance. PCMs will be enhanced with F/V and non-caloric beverages, which will require grocery shopping and meal preparation. The combination of PCMs and F/V provides all necessary nutrients specified by the Dietary Reference Intakes [36]. Participants who fail to achieve ≥ 5% weight loss at 6 months will not be eligible to continue and will be referred to our ongoing weight management programs or to other community resources for weight management. We targeted a minimum of 5% (~5–7kg) weight loss from baseline to 6 months as this level of weight loss is associated with reduced risk for chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and others [37–40]. Participants achieving a BMI of ≤ 22 kg/m2 prior to completion of weight loss will be transitioned to the weight maintenance diet, described below, prior to randomization.

Diet–Weight maintenance (0–12 months)

There are numerous approaches for dietary recommendations for weight maintenance. We were influenced by the Institute of Medicine dietary recommendations for weight maintenance [41], over 25 years experience with research trials and clinical weight management, and the desire to evaluate a practical and generalizable approach. Therefore, we will recommend a daily energy intake of estimated resting metabolic rate (RMR) * 1.4 to account for activities of daily living [42]. This recommendation theoretically results in a negative energy balance when the energy expenditure associated with prescribed PA is considered. However, we anticipate compensatory changes in components of energy balance such as increases in energy intake and/or decreases in components of total daily energy expenditure as the literature indicates most individuals regain weight subsequent to weight loss [2, 6–10]. Thus, we believe our approach will maximize the potential for weight maintenance and provides a reasonable compromise between scientific rigor, practicality, and generalizability. Participants will receive a meal plan with suggested servings of grains, proteins, fruits, vegetables, dairy, and fats, based on their energy requirements and the United States Department of Agriculture/Department of Health and Human Services Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 [43]. Participants will be encouraged (not required) to continue consuming a minimum of 14 PCMs per week and a minimum of 35 servings of F/V per week. We will provide participants with a list of commercially available low energy and low fat PCMs or they may purchase PCMs used during weight loss.

Weight loss/maintenance PA (−6 to 12 months)

Participants in both the phone and SL groups will be asked to perform moderate-to-vigorous PA (walking, jogging, biking, etc.), in a minimum of 10 minute bouts, across the 18-month trial. PA minutes will progress gradually from 45 minutes/week in week 1 (3 days × 15 minutes/day) to 300 minutes/week at the beginning of week 11 (5 days × 60 minutes/day) and remain at 300 minutes/week for the remainder of the intervention. Participants will also be asked to obtain at least 10,000 steps a day to prevent decreases in non-exercise physical activity. Pedometers will be provided to all participants. Participants will be asked to self-monitor PA by reporting daily minutes of PA and steps.

Health educators

Health educators will have backgrounds in nutrition, exercise physiology or behavioral counseling. All health educators will receive on-going training across the 18-month intervention to improve and maintain teaching skills, and to remain current with the latest weight management research. Training will include monthly visits from the program coordinator who will observe/listen to class presentations and provide suggestions for improvement, weekly staff meetings where lesson topics are discussed and presentations critiqued, and attendance at seminars and professional meetings. The potential for health educator bias will be minimized by randomly assigning educators to deliver one phone and one SL clinic concurrently. To assure standardized delivery of both intervention arms, all sessions will be audio recorded. The content of 20% of the recorded sessions will be compared with a checklist of required content. Health educators failing to deliver ≥ 80% of the required content will receive additional training to assure standardized delivery of the two interventions.

Phone conference intervention

During baseline assessments participants will be provided with written information explaining the basic logistics of the conference calls, which will be conducted using the Maestro conferencing system (Oakland, CA). Participants will be asked to dial a toll-free number 5 minutes prior to the scheduled meeting time and then enter a unique identifying code number that allows them to “enter” the meeting. In the interest of safety, participants will be asked to not call in situations where their attention is compromised, such as while driving, operating machinery, etc. Specific procedures relative to the conduct of the conference call, such as how to request to speak, courtesy to group members, reporting, confidentiality etc. will be discussed during the first phone session. Each session will include a check-in question to generate discussion regarding diet and PA, a review of compliance with the diet and PA protocols, a lesson on a weight management topic, and an experiential learning assignment that requires problem solving or the practice of behavioral weight management strategies to be completed prior to the next meeting. For example, assignments may include grocery shopping/meal planning to meet specific caloric or nutritional guidelines, eating in social situations or during holidays, food label reading, trying a new form of PA etc. Assignments will be discussed at the subsequent meeting, and the health educator will provide feedback. Midway between scheduled meetings, participants will be asked to report compliance to the diet and PA prescriptions and place orders for PCMs, which will be required during weight loss and optional during weight maintenance, using a web based entry system. Food orders will be delivered to participants’ residences by UPS within 3–4 days after placing the order.

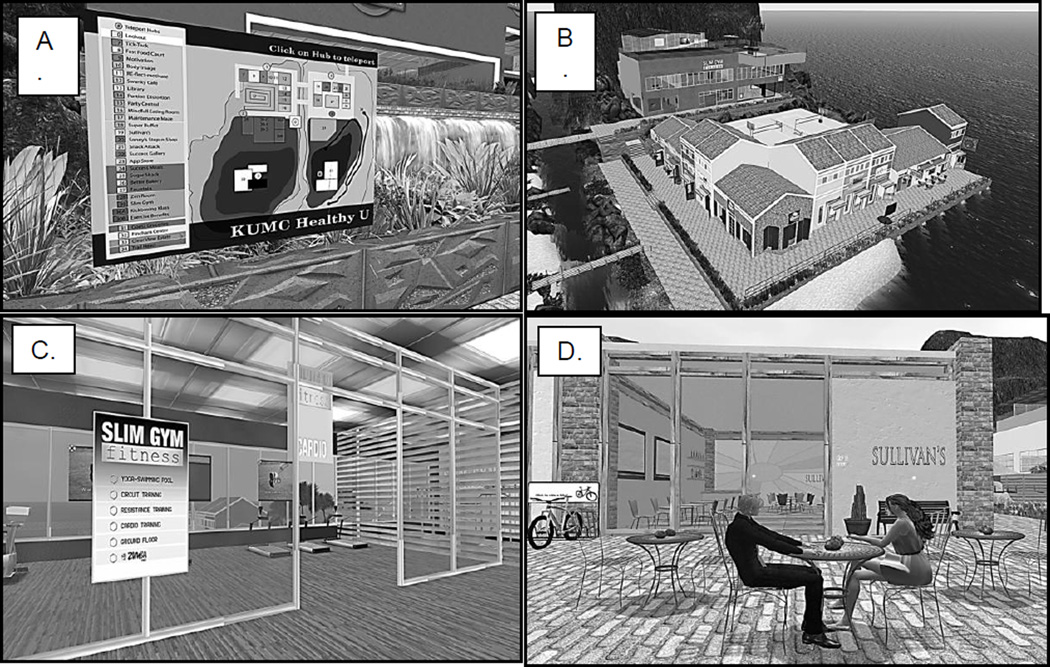

SL intervention

Participants randomized to the SL group for weight maintenance will be asked to register with SL, complete the on-line tutorial which explains the basic principles of working in SL, and create their avatar (virtual representation of themselves) prior to attending a 2-hour in-person session, conducted by research staff. This 2-hour session will teach participants how to navigate in SL and how to communicate with fellow group members and health educators via audio head-set provided by the study or chat using the computer keyboard. The SL group meetings will be conducted on a virtual “island” that is owned and maintained by the Department of Teaching and Learning Technology at the University of Kansas Medical Center. The “Healthy U” island is a beach resort that contains components known to be important for weight management. It includes a conference room for group meetings and numerous areas where learning experiences with real-time feedback can be conducted. These areas include a grocery store, restaurant, fitness center, walking trail, home with a stocked kitchen, buffet line, holiday party environment, etc. (Figure 2) Participants will be asked to log on to SL at least 5 minutes prior to the scheduled meeting time, where they will automatically be routed to a teleport map which provides access to all areas of the weight management center. To attend the group meeting they will select the conference room from the teleport map. As previously described, the meeting content and format will be identical for both the phone and SL groups. However, the SL and phone conference interventions differ in several important aspects. SL allows for both PowerPoint™ and videos to be incorporated in the educational sessions which is not possible on the group phone conference call. Participants in the SL group can complete assignments, designed to provide practice and reinforce behavioral strategies taught during group meetings, on their own schedule and repeat assignments as frequently as they choose, while receiving immediate feedback on their performance. This is in contrast to the phone group where assignments are completed in real life, and feedback is delayed until the following clinic meeting. For example, participants will be asked to go to the grocery store and select foods for a breakfast, lunch and dinner that satisfy specific energy and macronutrient requirements. Participants in the phone group would need to travel to an actual store to complete this assignment and would not receive feedback regarding their performance until the next scheduled group meeting. In contrast, SL participants could compete this assignment at the virtual grocery store, receive immediate feedback on their performance, and easily repeat the assignment if desired. Additionally, participants in the SL group can readily meet each other in SL outside of class time to develop a community of support, as opposed to the phone group where meeting outside of class time is more difficult due to distance, travel, child care, time restrictions, and scheduling.

Figure 2.

Screen captures of the “Healthy U” island. A.) Map of the island B.) Arial view of the resort including restaurants, grocery store, food markets, and the gym C.) The entrance to the gym D.) Two avatars outside of Sullivan’s restaurant.

Self-monitoring

Self-monitoring is an important predictor of adherence and treatment outcomes in weight management [44]. Therefore, participants in both the phone and SL groups will be asked to monitor body weight, the number of PCM’s and F/Vs consumed, minutes of PA, pedometer steps, and completion of homework assignments. Participants will submit self-monitoring data via a web-based data-entry page twice-weekly (mid-week, end of week) during the first 9 months and weekly thereafter. The health educators will use these data to stimulate discussion and facilitate problem solving during group meetings. Data on PCM use, F/V consumption, and homework assignments completed will be used in the mediation analysis described in the statistical analysis section.

Outcome Assessments (Table 1)

Table 1.

Outcome assessment schedule.

| Variable | Baseline (−6 mos.) |

Completion of weight loss (0 mos.) |

Midpoint of weight maintenance (6 mos.) |

Completion of weight maintenance (12 mos.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics a | X | X | X | X | |

| PA (7-day accelerometer) | X | X | X | X | |

| Energy/macronutrient intake (3-day food record) | X | X | X | X | |

| Self-efficacy for diet and PA (Questionnaires) | X | X | X | X | |

| Problem solving (Questionnaire) | X | X | X | X | |

| Self-monitoring (weight, PCMs, FV, PA) | Continuous | ||||

| Attendance/assignment tracking | Continuous | ||||

| Process evaluation | Continuous | ||||

Height, weight, waist circumference, body mass index.

Abbreviations: PA = Physical activity, PCMs = Portion controlled meals, F/V = Fruits and vegetables.

With the exception of PA, which will be assessed by accelerometry during free-living activity, outcome data for both intervention groups will be collected in our lab by trained staff at baseline (−6 months), following weight loss (0 months), and at the midpoint (6 months) and completion of weight maintenance (12 months).

Anthropometrics (weight, height, waist circumference)

Body weight (Belfour Inc., Model #PS6600, Saukville, WI) will be assessed between the hours of 6am and 10am following a 12 hour fast in a standard hospital gown, after attempting to void. Two measures within ±0.1 kg will be recorded and averaged. Standing height will be measured in duplicate to the nearest ± 0.1 cm using a wall-mounted stadiometer (Perspective Enterprises, Model PE-WM-60-84). BMI will be calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Waist circumference, as a surrogate for abdominal adiposity, will be assessed in triplicate (within ±2.0 cm) using the procedures described by Lohman et al [45]. The average of the 2 closest measurements will be used for analysis.

PA

Participants will wear an ActiGraph Model GT3X+ (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL) at the waist over the non-dominant hip for 7 consecutive days. Data collection intervals will be 1-minute, with a minimum of 12 hours constituting a valid day. The ActiGraph has been shown to provide valid assessments of PA during both laboratory (treadmill walking/running) [46, 47] and daily living activities [48–51]. The main outcome will be the average ActiGraph counts/minute over the 7-day period. Matthews et al. [52] have shown that a 7-day monitoring period provides measures of both PA and inactivity with a reliability of 90%. In addition, we will also assess the average number of min/day over 7 days spent at various activity levels using the cut-points used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey as described by Troiano et al. [53]. A SAS data reduction program will be used to complete the analyses described.

Energy and macronutrient intake

Prior to each scheduled outcome assessment visit, participants will be contacted by research staff and provided with both verbal and written instructions for completing a 3-day food record (2 weekdays, 1 weekend day). The food records will be reviewed by a registered dietitian at the assessment visit, and any necessary clarifications will be obtained. Food record data will be entered into the Nutrient Data System for Research (NDS-R; version 2014, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) for the determination of energy and macronutrient intake. All staff performing NDS-R data entry will be trained and must demonstrate reliability on computer coding (i.e. error rate < 10%) prior to entering study data.

Potential mediators

As a secondary aim, we are interested in the extent to which any effects of either the phone or SL interventions might be explained by potential mediators including PA, energy intake, consumption of PCMs and F/V, self-efficacy for both PA and diet, problem solving ability, attendance at group meetings, and completion of experiential learning assignments. Protocols for the assessment of PA, energy intake and consumption of PCMs and F/V have been described previously. Self-efficacy for PA will be assessed using the 5-item exercise self-efficacy scale [54]. Participants will rate their confidence level (1 = not confident at all to 7 = very confident) to engage in PA in a number of different situations including scheduling time for exercise, resisting lapse, etc. Self-efficacy for weight loss will be assessed using the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire [55], which has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of the potential to overeat in tempting situations [55, 56]. Participants will rate their level of confidence on a 10-point Likert-scale with higher values indicating greater confidence to resist overeating. Problem-solving abilities will be assessed using the Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised, short form (SPSI-R:S). The SPSI-R:S is a 25-item instrument with five component scales to assess problem-solving styles and solution generation [57]. Improvements in problem-solving skills assessed by the SPSI-R have been shown to partially mediate the association between treatment adherence and weight loss in response to a 6-month lifestyle intervention [58]. Both the Maestro conferencing system and SL provide automated tracking of individual participant’s meeting attendance, including meeting date and time spent in each meeting. In the phone group, completion of experiential learning assignments will be assessed by self-report. In the SL group, time spent on the island, completion of assignments, as well as all interactions between participants and components of the virtual weight management center, will be captured electronically and stored in an analyzable format on a secure server. A web service will run on a university web server which listens for communications sent from SL servers triggered by participants interacting with programs running on the “Healthy U” island. This web service will collect and store the data received on a secured file server. Data capture triggers, which detect participant’s interaction, are located throughout the virtual weight management center e.g. the conference room, grocery store, fitness center, and are also associated with all experiential learning assignments. Activating a trigger automatically sends data including location (e.g. restaurant, grocery store etc.) and/or activity (e.g. eating in a restaurant, grocery shopping assignments), avatar name, date, start time, and end time to the server in a format suitable for statistical analysis.

Process evaluation

A mixed-method process evaluation will be conducted to determine if the interventions were implemented as originally designed, assess participant satisfaction with the interventions, and potential competing factors which might contaminate or diminish the intervention effects. Intervention implementation will be assessed using information on diet (PCMs, F/V), PA (pedometer steps), meeting attendance, lesson content, and learning assignment completion. Assessments for these variables were described previously. Participant satisfaction, challenges and barriers to compliance with the intervention, and potential competing factors will be assessed by individual semi-structured interviews conducted at the conclusion of the trial (12 months) or immediately following drop-out.

Statistics

Sample size/power

Our primary aim is to compare between group differences (SL vs. phone conference call) in weight change during weight maintenance (0 to 12 months). Based on the results from our SL pilot trial [18], we hypothesize that both groups will regain weight, with significantly less regain in the SL compared with the phone group. Data from our trial using phone conference calls for weight loss and maintenance suggests that the phone group will regain approximately ~5.5 kg during the 12 months maintenance intervention with a standard deviation of ~6 kg [59]. Preliminary data from our SL pilot trial suggests no mean weight regain over 6 months of maintenance with a similar standard deviation (~6 kg) [18]. However, to be conservative in our sample size estimates we assumed a weight regain at 12 months of 2.5 kg with a standard deviation of 6 kg in the SL group. Likewise, we have been very conservative and have allowed for attrition rates of 10% during weight loss (drops + failure to achieve 5% weight loss) and 30% during weight maintenance. Estimated attrition rates were based on our experience with previous trials [16, 17, 30]. Power calculations, generated using nQuery Advisor®, indicated 64 evaluable participants per group (total n = 128) provides 80% power assuming a type I error rate of 5%. Therefore, based on our assumptions for attrition, 101 participants per group (total n = 202) will be needed to enroll in this trial.

Analysis plan: Primary outcomes

We will conduct both an intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis for our primary aim. Weight regain post weight loss (weight at 12 months minus weight at 0 months) between intervention groups will be compared using a two-sample t-test. Secondarily, a linear mixed model will be utilized to longitudinally compare the weight change at 6 and 12 months (weight at month 6 – weight at month 0 and weight at month 12 – weight at month 0, respectively) between the two groups assuming an autoregressive correlation structure over time. Similar analyses will be completed for each of the secondary endpoints including PA (accelerometry), energy and macronutrient intake, F/V, self-efficacy for diet and PA, attendance and completion of experiential learning assignments. Baseline variables including age, sex, BMI, and waist circumference will be included as covariates in the linear mixed models to assess their potential moderating effect on both primary and secondary outcomes.

Analysis plan: Secondary outcome

We are interested in the extent to which any effects of either the phone or SL interventions on weight regain during weight maintenance might be explained by potential mediators including PA, energy intake, consumption of PCMs and F/V, self-efficacy for both PA and diet, problem solving ability, attendance at group meetings, and completion of experiential learning assignments. Mediation will be examined using techniques based on the work of Baron and Kenny [60] and further developed by MacKinnon [61] and Brown [62]. The criteria for mediation are: 1) a significant difference between SL and phone groups for change in weight (0 to 12 months); 2) a significant difference between SL and phone groups for change in mediators (0 to 12 months); 3) a significant association between change in mediators and change in weight (0 to 12 months); and 4) intervention effects must be attenuated by the presence of the mediator in the statistical model. Analyses for criteria 1 and 2 are described above. Criterion 3 will be evaluated by constructing a sequence of independent linear mixed models to determine if potential mediators are associated with our primary outcome (weight change 0 to 12 months). Criterion 4 will be evaluated only for potential mediators satisfying criterion 3. A linear mixed model will be created with the potential mediator and intervention condition (SL vs. phone) and weight change 0 to 12 months. An attenuation in the association between intervention condition and weight change 0 to 12 months, with the potential mediator included or excluded from the model, indicates some level of mediation. These steps will enable us to determine if full mediation or partial mediation is present. Full mediation would occur if inclusion of the mediation variable drops the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable to zero. Partial mediation implies that there is not only a significant relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable, but also some direct relationship between the independent and dependent variable. There is also the possibility that potential mediators may be important only for one, but not both, treatment groups, or a potential mediator may have extremely different effects depending on treatment group. This possibility will be evaluated by examining the interaction between treatment group and the potential mediator. A significant interaction indicates no mediation. Thus, this potential mediator will be examined within rather than across treatment requiring separate models for each treatment condition.

DISCUSSION

There is a need for the development and evaluation of effective alternative strategies for maintaining weight loss that diminish or eliminate barriers and/or enhance the traditional in-person approach. The internet has become a popular platform for delivering behavioral, health-related interventions as they may offer a cost-effective alternative to traditional in-person interventions, with the potential to reach large numbers of individuals while reducing barriers to participation (e.g. travel, child care costs etc.), and providing anonymity. [55–57]. Internet based virtual reality platforms, such as SL, may be an effective approach for weight maintenance, as there is evidence to suggest that skills and behaviors acquired in virtual environments transfer to the “real world”[63]. However, the effectiveness of weight maintenance interventions delivered in SL has not been established.

This paper describes the rationale and design for a randomized trial to compare a behavioral weight maintenance intervention (12 months) delivered by phone conference call or in the SL virtual environment. Several conceptual aspects of intervention delivery in SL suggest that this approach may be effective for weight maintenance. Behavior change in SL is supported by an interactive, secure experiential learning environment that closely mirrors the physical world. The SL learning environment provides rapid dynamic feedback, learner experimentation, real-time personalized task selection, the opportunity for repeated exploration and practice of new behaviors, and social support, all of which may improve participant confidence and acquisition of weight management skills. For example, in SL participants in their virtual representation (avatar) can engage in activities such as such as grocery shopping for low calorie foods, selecting foods at a restaurant or holiday party etc. without real life consequences.

Strengths of this trial include: 1) a design specific to evaluating two potentially effective strategies for the delivery of a weight management intervention which introduces a new technology (SL) for half of the sample during weight maintenance; 2) Both technologies evaluated are readily available and accessible. Phone use is ubiquitous in the US and ~77% of US households have a computer with internet connection and another 9% of households have internet access at other locations [64]. Thus, if successful, the interventions could be widely disseminated; 3) the use of PCMs to standardize the method of weight loss to reduce potential bias for subsequent comparison of the two delivery systems (phone vs. SL) for weight maintenance; 4) Adequate statistical power for evaluation of our primary aim; 5) inclusion of both mediation and process analyses.

Overall, strategies are needed to improve the success rates of weight maintenance after weight loss. If successful this study will provide a novel technique, using remote education and readily available technology, to improve weight maintenance after a weight loss intervention.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their time spent to developing this project Jeffery Honas, Christie Gomez, Felicia Steger, Sonny Painter, Kendra Spaeth, and Dinesh Pal Mudaranthakam.

Funding: National Institutes of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01- DK094833) We acknowledge HMR Weight Management Services Corp. for providing the pre-packaged meals.

Clinical trials registration: NCT01841372

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations

VR- Virtual reality

PA- Physical Activity

SL-Second Life

PCM- Portion Controlled Meals

F/V- Fruits and Vegetables

SCT- Social Cognitive Theory

Contributor Information

JR Goetz, Email: jgoetz@kumc.edu.

CA Gibson, Email: cgibson@kumc.edu.

MS Mayo, Email: mmayo@kumc.edu.

RA Washburn, Email: rwashburn@ku.edu.

Y Lee, Email: yjlee@ku.edu.

LT Ptomey, Email: lptomey@kumc.edu.

JE Donnelly, Email: jdonnelly@ku.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1855–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foreyt JP, Goodrick GK. Evidence for success of behavior modification in weight loss and control. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:689–701. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Racette S, Schoeller D, Kushner R, Neil K, Herling-Iaffaldano K. Effects of aerobic exercise and dietary carbohydrate on energy expenditure and body composition during weight reduction in obese women. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1994;61:486–494. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meckling KA, O'Sullivan C, Saari D. Comparison of a low-fat diet to a low-carbohydrate diet on weight loss, body composition, and risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease in free-living, overweight men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2717–2723. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Jama. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barte JC, Ter Bogt NC, Bogers RP, Teixeira PJ, Blissmer B, Mori TA, et al. Maintenance of weight loss after lifestyle interventions for overweight and obesity, a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toubro S, Astrup A. Randomised comparison of diets for maintaining obese subjects' weight after major weight loss: ad lib, low fat, high carbohydrate diet vs fixed energy intake. BMJ. 1997;314:29–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7073.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Kettel Khan L, Gillespie C, Serdula MK. Weight regain in U.S. adults who experienced substantial weight loss, 1999–2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelan S, Wing RR, Loria CM, YK, Lewis CE. Prevlance and predictors of weight-loss maintenance in a biracial cohort: Results from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borg P, Kukkonen-Harjula L, Fogelholm M, Pasanen M. Effects of walking or resistance training on weight loss maintenance in obese, middle-aged men: a randomized trial. International journal of obesity (2005) 2002;26:676–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraschnewski JL, Boan K, Esposito J, Sherwood NE, Lehman EB, Kephart DK, et al. Long-term weight loss maintenance in the United States. International journal of obesity (2005) 2010;34:1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63:2985–3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Phelan S, Sarwer DB, Sanderson RS. Obese patients' perceptions of treatment outcomes and the factors that influence them. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2133–2139. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perri MG, Nezu PAM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2001;69:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foreyt J, Poston W. The challenge of diet, exercise and lifestyle modification in the management of the obese diabetic patient. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:S5–S11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnelly JE, Goetz J, Gibson C, Sullivan DK, Lee R, Smith BK, et al. Equivalent weight loss for weight management programs delivered by phone and clinic. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2013;21:1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/oby.20334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambourne K, Washburn RA, Gibson C, Sullivan DK, Goetz J, Lee R, et al. Weight management by phone conference call: a comparison with a traditional face-to-face clinic. Rationale and design for a randomized equivalence trial. Contemporary clinical trials. 2012;33:1044–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan DK, Goetz JR, Gibson CA, Washburn RA, Smith BK, Lee J, et al. Improving weight maintenance using virtual reality (Second Life) Journal of nutrition education and behavior. 2013;45:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith S. Second Life Mixed Reality Broadcasts: A Timeline of Practical Experiments at the NASA CoLab Island. Journal For Virtual Worlds Research. 2008;1 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulos MNK, Hetherington L, Wheeler S. Second Life: an overview of the potential of 3-D virtual worlds in medical and health education. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2007;24:233–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston JD. In: Innovation in Weight Loss Intervention Programs: An Examination of a 3D Virtual World Approach. Anne PM, Celeste D, editors. 2012. pp. 2890–2899. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beard L, Wilson K, Morra D, Keelan J. A survey of health-related activities on second life. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1999;67:132–138. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messinger PR, Stroulia E, Lyons K, Bone M, Niu RH, Smirnov K, et al. Virtual worlds -- past, present, and future: New directions in social computing. Decis Support Syst. 2009;47:204–228. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982;12:871–878. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor H, Jacobs D, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon A, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31:741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zemel MB, Donnelly JE, Smith BK, Sullivan DK, Richards J, Morgan-Hanusa D, et al. Effects of dairy intake on weight maintenance. Nutr Metab. 2008;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeCheminant JD, Gibson CA, Sullivan DK, Hall S, Washburn R, Vernon MC, et al. Comparison of a low carbohydrate and low fat diet for weight maintenance in overweight or obese adults enrolled in a clinical weight management program. Nutr J. 2007;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donnelly JE, Smith BK, Dunn L, Mayo MS, Jacobsen DJ, Stewart EE, et al. Comparison of a phone vs clinic approach to achieve 10% weight loss. International journal of obesity (2005) 2007;31:1270–1276. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psych Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marlatt G, Gordon J. Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prochaska JO, Marcus BH. The transtheoretical model: applications to exercise. Exercise Adherence II. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psych. 1994;13(1):39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intake for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. Washington: National Academic Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, Lee IM, Appel LJ, Smith West D, et al. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase II. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Applegate WB, Ettinger WH, Jr, Kostis JB, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (tone) JAMA. 1998;279:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intake for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. Washington: National Academic Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mifflin MD, St Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, Koh YO. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1990;51:241–247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. [Accessed 5/1/2011];2010 http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/dietaryguidelines.htm.

- 44.Sarwer DB, Wadden TA. The treatment of obesity: what's new, what's recommended. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:483–493. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998:777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brage S, Wedderkopp N, Franks PW, Anderson LB, Froberg K. Reexamination of validity and reliability of CSA monitor in walking and running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1447–1454. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000079078.62035.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sirard J, Melanson E, Li L, Freedson P. Field evaluation of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. physical activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:695–700. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200003000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendelman D, Miller K, Baggett C, Debold E, Freedson P. Validity of accelerometry for the assessment of moderate intensity physical activity in the field. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(Suppl):S442–S449. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Bassett DR, Jr, O'Brien WL, King GA, Ainsworth BE. Estimation of energy expenditure using CSA accelerometers at hip and wrist sites. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S450–S456. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bassett D, Ainsworth BE, Swartz A, Strath SJ, O'Brien WL, King GA. Validity of four motion sensors in measuring moderate intensity physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S471–S480. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matthews CE, Ainsworth BE, Thompson RW, Bassett DRJ. Sources of variance in daily physical activity levels as measured by an accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1376–1381. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd K, Masse LC, Tilert T, MacDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1992;63:60–66. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10607557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark M, Abrams DB, Niaura RS. Self-efficacy in weight management. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1991;59:739–744. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glynn SM, Ruderman AJ. The development and validation of an Eating Self-Efficacy Scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1986;10:403–420. [Google Scholar]

- 57.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised: Technical Manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murawski ME, Milsom VA, Ross KM, Rickel KA, DeBraganza N, Gibbons LM, et al. Problem solving, treatment adherence, and weight-loss outcome among women participating in lifestyle treatment for obesity. Eat Behav. 2009;10:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donnelly JE, Goetz J, Gibson C, Sullivan DK, Lee R, Smith BK, et al. Equivalent weight loss for weight management programs delivered by phone and clinic. Obesity. 2013;21:1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/oby.20334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention and intervention research. NIDA Res Monogr. 1994;139:127–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown RL. Assessing specific mediational effects in complex theoretical models. Structural Equation Modeling. 1997;4:142–156. [Google Scholar]

- 63.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 2010. NHLBI Working Group: Virtual Reality Technologies for Research and Education in Obesity and Diabetes Executive Summary. [retrieved October 2011]; from http://wwwnhlbinihgov/meetings/workshops/vrhtm.

- 64.U.S. Department of Commerce: National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Digital Nation: 21st Century America's Progress Toward Universal Broadband Internet Access [Google Scholar]