Abstract

Background: The Texas Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration project (TX CORD) uses a systems-oriented approach to address obesity that includes individual and family interventions, community-level action, as well as environmental and policy initiatives. Given that randomization is seldom possible in community-level intervention studies, TX CORD uses a quasi-experimental design. Comparable intervention and comparison study sites are needed to address internal validity bias.

Methods: TX CORD was designed to be implemented in low-income, ethnically diverse communities in Austin and Houston, Texas. A three-stage Geographical Information System (GIS) methodology was used to establish and ascertain the comparability of the intervention and comparison study sites. Census tract (stage 1) and school (stage 2) data were used to identify spatially exclusive geographic areas that were comparable. In stage 3, study sites were compared on demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status (SES), food assets, and physical activity (PA) assets. Student's t-test was used to examine significant differences between the selected sites.

Results: The methodology that was used resulted in the selection of catchment areas with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics that fit the target population: ethnically diverse population; lower-median household income; and lower home ownership rates. Additionally, the intervention and comparison sites were statistically comparable on demographic and SES variables, as well as food assets and PA assets.

Conclusions: This GIS approach can provide researchers, program evaluators, and policy makers with useful tools for both research and practice. Area-level information that allows for robust understanding of communities can enhance analytical procedures in community health research and offer significant contributions in terms of community assessment and engagement.

Introduction

With multiple levels of influence contributing to the staggering rates of childhood obesity, the NIH and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) have recommended a systems-oriented approach to tackle the disease.1 A clearly structured and appropriately designed systems-oriented approach should include individual and family interventions,2 along with community-level action through educational, environmental, and policy initiatives.3,4 This recommendation is in line with promising outcomes seen as a result of recent obesity interventions that employed multifaceted strategies with an emphasis on the role of community support.5–7 There is an increasing call for researchers and policy makers to explore opportunities that allow for the implementation of systems-oriented initiatives in communities. Moreover, the importance of the experimental evaluation of these systems-oriented approaches on childhood obesity has also been highlighted.8

The CDC Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (CORD) program, which is being implemented in several communities nationwide, was designed to assess a systems-oriented approach for the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity. The CORD systems-oriented obesity prevention model addresses the drivers of obesity within multiple sectors, including primary healthcare clinics, early care and education, elementary schools, and community organizations. It also operates at multiple levels, including the child, family, organizations, and community environment. It provides connectivity and feedback between the multiple sectors and levels. The overall aim of the CORD project is to implement evidence-based healthcare and community strategies that support 2- to 12-year-old children's healthy eating and active living and help to inform obesity reimbursement in a Medicaid-eligible population. The TX CORD project, which includes both primary and secondary intervention strategies, is one of the three CORD sites nationwide. The community primary prevention program follows a quasi-experimental design where obesity prevention and treatment efforts are reinforced and promoted in healthcare and school settings for children ages 2–12 years and their families. The secondary prevention program follows a randomized, controlled trial design where participating children are randomized to either a 12-month family-based, community-focused obesity treatment or a standard of care.

For the TX CORD project, as with many community-wide intervention studies, randomization was not feasible, so a quasi-experimental design was used. In quasi-experimental designs, it is necessary to manage threats to internal validity, such as selection bias.9 Selection bias can occur in multilevel studies through the selection of the ecological units themselves.10 To control for selection bias in the TX CORD study, it was necessary to ensure that the area-level obesity-related characteristics of the communities for both treatment and comparison participants were similar at baseline. In community-based interventions, there could also be threats to external validity with the study population not representing the target population. The utility of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to control for both sampling and external validity biases is apparent in the spatial analyses capabilities of the GIS technology.

GIS software allows researchers to organize, process, and display spatial data—data connected to a specific and known location on the earth's surface, such as a point (the location of a grocery store), line (a particular street), or polygon (a census tract). One of the most useful applications of GIS for researchers is to facilitate the incorporation of environmental variables into a data set. GIS can be used to select study areas based on predetermined characteristics of interest, as Parmenter and colleagues did.11 GIS can also help with the selection of comparable study areas and reduce selection bias in quasi-experimental (ecological) studies such as TX CORD. For this purpose, two specific GIS tasks are employable: (1) display existing data spatially, by identifying a particular geographic entity (e.g., all census tracts in Austin, Texas) and assigning variables of interest (e.g., the median household income) to the spatial entity, and (2) generate new data through the use of various proximity analyses protocols (e.g., the number of grocery stores in a census tract). Subsequent to these spatial analyses, geographic entities (e.g., census tracts) that have similar variables (e.g., stores) can be spatially identified and grouped as comparable entities.

A variety of factors at the community level contribute to the risk of childhood obesity in the United States.4 For community-based obesity prevention studies, data on the demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status (SES), food assets, and physical activity (PA) assets need to be considered as part of the sampling strategy. GIS allows for spatial analyses of these data beyond what is possible with analyses of textual data.

Area-level demographic and SES characteristics have been shown to affect obesity-related behaviors and obesity rates.2,12–16 The community food environment represents public places where food can be obtained (convenience, specialty and grocery stores, restaurants, and so on).4,17 The availability and proximity of different food outlet types in the community may affect dietary behavior and, consequently, influence patterns of obesity in the community. Compared to eating at home, people eating at restaurants typically consume more calories and fewer fruits, vegetables, and fiber18–20 and, consequently, gain more weight.21,22 Lower-SES environments have been shown to have a higher density of fast food outlets,23 which, in turn, is associated with higher energy and fat intake.18 The availability of supermarkets has been associated with a better-quality diet24 and lower prevalence of obesity and overweight in both adults25 and adolescents.26

PA assets in the community may also affect obesity risk. PA assets are places in the built environment that are designed to support active lifestyle. They include parks, trails, playgrounds, and recreational facilities.4 A review of the literature concluded that living near recreational areas, playgrounds, and parks was related to children's total PA levels.27 Another study found that fewer recreational facilities in lower-SES and high-minority areas are potentially related to decreased PA and increased overweight.28,29

The aim of this article is to describe how GIS approaches were used to select the intervention and comparison catchment areas for the TX CORD project. The data described above were used to delineate the catchment areas from which TX CORD participants were recruited (i.e., demographic characteristics, SES, food assets, and PA assets). These methods have the potential to provide program evaluators, researchers, and policy makers with objective tools that are useful for strategic planning in both research and practice.

Methods

TX CORD is a childhood obesity prevention demonstration project designed to be implemented in low-income, ethnically diverse catchment areas in Austin and Houston. The determination of the comparability between the intervention and comparison catchment areas was conducted in three stages. In stage I, census tract data were used to identify spatially exclusive geographic areas that would comprise the intervention and comparison catchment areas. In stage II, relevant school-level data were used to select candidate schools within the established catchment areas. In stage III, statistical testing was used to compare the attendance zones of the candidate schools in the intervention area with those in the comparison area.

Stage I: Establishing the Study Catchment Areas

Various steps were taken toward establishing comparable catchment areas that were based on objective area-level measures of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Census tract data were used to create a composite index for racial/ethnic diversity and SES for both Austin and Houston. The boundaries of the TX CORD catchment areas were based on this composite index.

Data and data sources

The variables included the percentage of population that was non-Hispanic black, percentage Hispanic, the percentage of people older than 25 years with no more than a 12th-grade education, the percentage of families within 185% of the poverty line with children under the age of 18 years, and percentage of homes valued less than $100,000 (see Table 1).30

Table 1.

A Depiction of the Process That Was Used To Process the Area-Level (Census Tract) Variables That Were Sourced from the US Census Bureau

| Variables (US Census Bureau 2005–2009; ACS)30 | No. of variables | Score (quintile) |

|---|---|---|

| Percent African American/black | (1) | 1–5 |

| Percent Hispanic | (2) | 1–5 |

| Percent of >25 year olds with no more than 12th-grade education | (3) | 1–5 |

| Percent under 185% poverty; families with <18 year olds | (4) | 1–5 |

| Percent of houses with value less than 100K | (5) | 1–5 |

| Composite index (score) | 5–25 |

Data processing

Using ArcGIS Software 10.1 (Esri Corporation, Redlands, CA), data on the selected variables were joined with the census tract map of each city. Scores (from 1 to 5) were assigned to each census tract based on its position in the quintile distribution of each variable (Table 1). The scores on the variables for each census tract were tallied (minimum=5 and maximum=25) into a new variable that was labeled as the composite index score. Thereafter, the composite index score was grouped into quintiles, resulting in the following categories: 5.0–9.0 (quintile 1); 9.1–14.0 (quintile 2); 14.1–18.0 (quintile 3); 18.1–20.0 (quintile 4); and 20.1–25.0 (quintile 5). Thus, the census tracts with high minority population and low income will fall in quintile 5. These data-processing steps were conducted separately for the TX CORD study cities (Austin, Texas, and Houston, Texas).

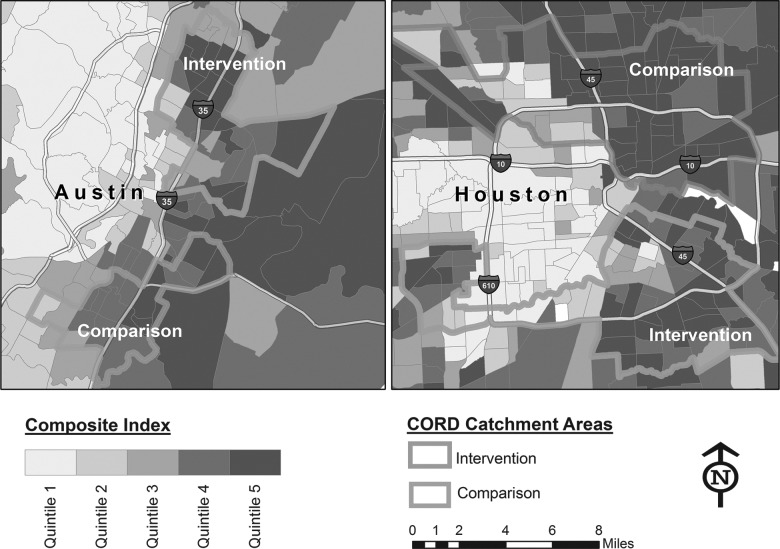

The catchment area boundaries were drawn around a collection of contiguous census tracts that fell in the higher quintiles of our index. Figure 1 shows a thematic map that depicts these categories as a spectrum of color from light brown (lowest quintile) through dark brown (highest quintile). Using these steps, a pair of comparable catchment areas (intervention and comparison) was selected for each study city.

Figure 1.

Maps of TX CORD cities (Austin, Texas, and Houston, Texas), showing the boundaries of the intervention and comparison catchment areas—drawn as a continuous line (green=intervention and blue=comparison) around contiguous census tracts that fall in the higher quintiles of the composite index.

Stage II: Selecting Candidate Schools from Intervention and Comparison Catchment Areas

The objective for this stage was to select study schools that would be comparable between the intervention and comparison areas and generalizable to the target population. Schools were selected because the TX CORD intervention included a school-based obesity prevention program to be implemented in elementary schools.

Data and data sources

Here, the following school-level variables were used: school enrollment numbers, percent non-Hispanic black, percent Hispanic, percent non-Hispanic white, (race/ethnicity), and percent free and reduced lunch participation (economic disadvantage), which are annually collected and publicly available. Children in Texas public schools between grades 3 and 12, and who are enrolled in a physical education class, are required to participate in FITNESSGRAM® (The Cooper Institute, Dallas, TX) testing.31,32 FITNESSGRAM was selected for assessing student physical fitness in Texas following the passing of Senate Bill 530.24 in 2007. The FITNESSGRAM is a field test of physical fitness parameters, including cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, abdominal and back muscular strength and endurance, upper-body muscular strength and endurance, and lower-back/hamstring flexibility.33 The current study used data on percentage of students that met both FITNESSGRAM BMI and Cardiorespiratory Fitness Zone Standards. All school-level data were sourced from the Texas Education Agency (www.tea.state.tx.us).

Data processing

Data were assembled for all the elementary schools located inside the catchment boundaries that were established in stage I. Comparing the schools to one another, a set of similar schools were selected from the intervention and comparison catchment areas, using the criteria that potential study schools would contain a predominantly minority student body (≥80%) and have high participation rate in the free and reduced lunch program (≥90%). Using this approach, 33 candidate elementary schools were selected from the intervention catchments areas in Austin and Houston, while 15 candidate schools were selected from the comparison catchment areas in both cities. The geographic and population profiles of the TX CORD study areas are presented in Table 2.34

Table 2.

Geographic and Population Profiles of TX CORD Catchment Areas

| Intervention | Comparison | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All census tractsa | Attendance zonesb | All Census Tractsa | Attendance zonesb | |||||

| No. of units | Population | No. of units | Population | No. of units | Population | No. of units | Population | |

| Houston, TX | 79 | 327,667 | 15 | 117,729 | 64 | 254,939 | 10 | 71,579 |

| Austin, TX | 36 | 155,959 | 18 | 106,958 | 24 | 114,189 | 5 | 30,966 |

| Totals | 115 | 483,626 | 33 | 224,687 | 88 | 369,128 | 15 | 102,545 |

Data for (1) all census tracts in each of the four demarcated catchment areas and (2) the candidate schools attendance zones in each of the four demarcated catchment areas. 2010 US decennial census.34

All census tract data (no. of units and population) were sourced from the Esri Business Analyst suite (BA), using the US Census data engine in BA. Reported data are exactly the same information that is available on the census website.

School attendance zones boundaries (no. of units) were sourced from the Austin Independent School District and Houston Independent School District. Attendance zones boundaries are not standard US Census geographies. Population data for attendance zones were derived from an interpolation process in BA that is based on 2010 census data.

TX CORD, The Texas Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration project.

Stage III: Comparisons of Candidate Schools' Neighborhood Characteristics

Here, the objective was to compare the neighborhood characteristics of the candidate schools in the intervention catchment area with those in the comparison catchment area. The data for these comparisons were collected in the attendance zones of the candidate elementary schools. In Texas, school attendance zones are established by each school district as the geographic areas from which children are assigned to schools. Schools generally draw their student population from households located within their particular attendance zone, unless the school hosts a magnet program or special academy.

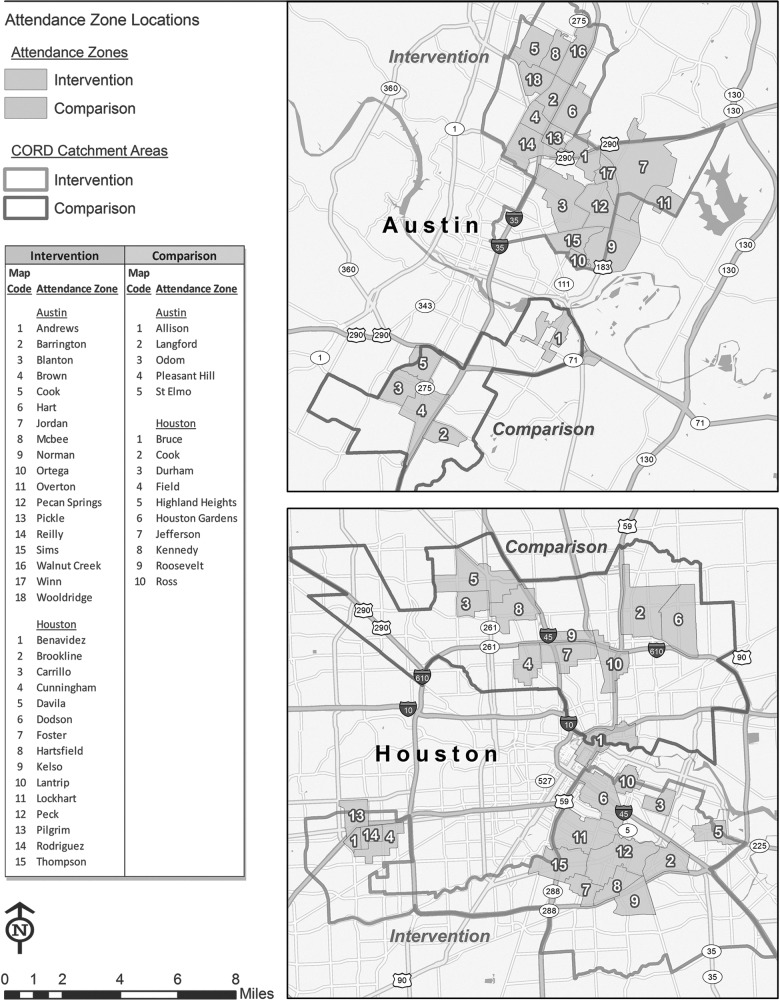

There were 33 attendance zones and 15 attendance zones in the intervention and comparison catchment areas, respectively. Figure 2 shows these school attendance zones inside the demarcated catchment areas. Four classes of neighborhood characteristics were examined: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) SES; (3) food assets; and (4) PA assets. Although food and PA assets are potentially modifiable environmental characteristics, they were included in the current analysis in order to identify baseline differences between the intervention and comparison areas, while using the school attendance zone as unit of analysis.

Figure 2.

Maps of TX CORD cities (Austin, Texas, and Houston, Texas), showing the attendance zones of the candidate schools. All the candidate schools, and their attendance zones, were selected from inside the catchment areas that were demarcated in stage I.

Data and data sources

More details on the demographic and socioeconomic data that were used are provided in Supplementary Table 1 (see online supplementary material at www.liebertpub.com/chi). Demographic data included race/ethnicity, age, and gender. Socioeconomic data included education, household types, and income. Food assets data included the density of convenience stores, grocery stores, full service restaurants, and fast food restaurants. Using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes, fast food restaurants were selected from the full service restaurant list (NAICS: 7221). Specifically chosen were the fast food restaurants that were listed as the “2010 Top 50 Limited-Service Restaurants” by QSR Magazine (www.qsrmagazine.com), which provides information on the limited-service restaurant industry. In addition to the QSR list, and based on local knowledge of Texas limited-service restaurants, other regionally significant establishments were added to the fast food category. For grocery stores, businesses were included that had NAICS codes beginning with 44511. This included food markets, grocers, and supermarkets, but excluded convenience stores. For PA assets, data gathered included sports and recreational centers (health and fitness clubs, public and private pools, tennis courts, skating rinks, and so on) and park areas. Sports and recreational centers were identified using the NAICS codes beginning with 71394. More details on the NAICS codes that were used are provided in Supplementary Table 2 (see online supplementary material at www.liebertpub.com/chi). Density of park area was calculated as the proportion of the attendance zone land area that is covered by parks.

Most of the data were sourced from the Esri Business Analyst application package (Esri Corporation). Business Analyst contains a variety of spatially referenced data sets on commercial and retail interests necessary for robust assessment of the built environment. Esri extracts its business data from a comprehensive list of businesses licensed from Infogroup®. This business list contains data on more than 12 million US businesses—including the business location, franchise code, industry classification code, and the sales volume among other attributes. Business Analyst also contains demographic and income data that were originally collected by the US Census Bureau (Census 2010). In addition to Esri data repositories, regional data were also sourced from various local GIS clearinghouses, including governmental offices at the state (Texas), local council of governments, and city offices. Specific information on data sources can be found in Supplementary Table 1 (see online supplementary material at www.liebertpub.com/chi).

Data processing

The ArcGIS Software 10.1 (Esri Corporation) and the Esri Business Analyst Desktop Software (data included) were used for the spatial integration and analysis of the relevant data. The attendance zone served as the spatial unit of analysis (i.e., the unit at which relevant data were aggregated). To collect the relevant data on each attendance zone, GIS file (shapefile) of the TX CORD schools' attendance zones was incorporated into the Business Analyst suite, analyzing each site (Austin/Houston) separately. The “get reports” function in Business Analyst was used to extract the relevant demographic characteristics and SES data for each attendance zone. For all the food assets and PA assets in each attendance zone (except parks), the attendance zone layer was spatially joined to the specific feature layer (e.g., grocery stores) in ArcGIS. Thereafter, the GIS program generated a count of the selected feature for each attendance zone. The intersect function in ArcGIS was used to calculate the park area for each attendance zone. Here, the attendance zones shapefile was overlaid on a city-wide shapefile of park areas. Thereafter, the intersect tool in ArcGIS was used to extract park areas that coincided with attendance zones. A new shapefile resulted from this exercise, which provided the total land area (square miles) of parks in each attendance zone.

Statistical Analysis

The Stata statistical software (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses. Series of two-sample t-tests were performed to determine whether there was a significant difference on each of the selected neighborhood characteristics between the attendance zones in the intervention versus those in the comparison catchment areas. For this analysis, the candidate attendance zones in both (Austin and Houston) intervention catchment areas were assembled into one group, and those in the comparison catchment areas for both cities were assembled into a separate group. Second, using the two-sample t-test, we compared the neighborhood characteristics of all the candidate attendance zones (intervention and comparison) in Austin with those in Houston. A type I error level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Results

Overall, the majority of the residents in the candidate attendance zones were Hispanic (54%) and included slightly more males (52%) than females. The median age was 31 years, with approximately 20% of children under the age of 18. The adult educational attainment was generally low, with 27% high school graduates and 36% less than a high school education. The majority of households were composed of families (86%) with more “both-parents” (56%) than “single-parent” (44%) present. The median household income was $31,315. Full service restaurants had the highest density of all the food outlets, at 9.0 per square mile, and grocery stores were 3.0 per square mile. Fitness club and recreational facility availability was 0.3 per square mile, and 0.05% of land area was covered by parks.

For comparisons between the intervention and comparison attendance zones across both cities, only 6 of 47 variables were statistically significant. The percentage of Asian and Pacific Islander was 2.3% in the intervention area, but 0.8% in the comparison area (p=0.006). There were age-related differences in percentages of children ages 0–4, with 1.7% greater in the intervention group (p=0.021) and 4.3% fewer adults ages 35–64 (p=0.001) in the intervention group. The difference in housing tenure (p=0.034) was 38.1% for owner-occupied housing in the intervention catchment versus 49.1% in the comparison catchment. There were 4.5% fewer adults with only a high school education in the intervention area, compared to the comparison area (p=0.014). All other variables showed no significant differences between intervention and comparison catchment areas (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparing TX CORD Candidate School Attendance Zones in the Intervention Catchments with Those in the Comparison Catchment Areasa

| Intervention (n=33)b | Comparison (n=15)b | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Total population | 224,687 | (3075.30) | 102,545 | (3340.00) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 14.9 | (13.20) | 20.9 | (19.70) | 0.215 | |

| Black | 24.5 | (24.98) | 24.7 | (27.04) | 0.978 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.3 | (1.90) | 0.8 | (0.64) | 0.006 | ** |

| Other race | 1.3 | (0.56) | 1.3 | (0.59) | 0.732 | |

| Hispanic origin (any race) | 51.1 | (26.62) | 47.1 | (22.38) | 0.614 | |

| Minority population | 85.9 | (10.94) | 78.6 | (19.34) | 0.099 | |

| Age, years (%) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 9.3 | (2.37) | 7.6 | (1.88) | 0.021 | * |

| 5–19 | 21.5 | (4.09) | 19.7 | (4.71) | 0.184 | |

| 20–34 | 28.9 | (6.20) | 26.4 | (8.30) | 0.247 | |

| 35–64 | 32.5 | (2.97) | 36.8 | (4.70) | 0.001 | ** |

| ≥65 | 7.8 | (4.02) | 9.5 | (4.31) | 0.175 | |

| Gender distribution (%) | ||||||

| Male | 51.5 | (3.30) | 52.2 | (7.41) | 0.645 | |

| Female | 48.5 | (3.30) | 47.8 | (7.41) | 0.645 | |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Education of those over 25 (%) | ||||||

| Total population over 25 years | 92,577 | 129,743 | ||||

| <HS | 36.7 | (14.88) | 35.8 | (12.24) | 0.842 | |

| HS grad | 25.3 | (5.74) | 29.8 | (5.41) | 0.014 | * |

| Some college and associates | 20.8 | (6.84) | 20.6 | (6.44) | 0.934 | |

| Bachelors or grad | 17.2 | (9.91) | 13.8 | (9.09) | 0.261 | |

| Household types (%) | ||||||

| Households with 1 person | 27.3 | (8.02) | 28.7 | (8.59) | 0.588 | |

| Households with 2+people | ||||||

| Family households | 85.8 | (6.64) | 86.4 | (7.77) | 0.810 | |

| Both parents | 54.9 | (7.75) | 57.6 | (10.04) | 0.302 | |

| With own children | 51.7 | (11.81) | 45.7 | (8.53) | 0.084 | |

| Single parent | 45.1 | (7.75) | 42.3 | (10.07) | 0.298 | |

| With own children | 48.9 | (8.83) | 44.8 | (7.86) | 0.242 | |

| Nonfamily households | 14.2 | (6.64) | 13.6 | (7.77) | 0.810 | |

| Family household size (%) | ||||||

| ≤4 persons | 72.8 | (7.47) | 75.6 | (8.13) | 0.252 | |

| >4 persons | 27.2 | (7.47) | 24.4 | (8.13) | 0.252 | |

| Households by tenure (%) | ||||||

| Owner occupied | 38.1 | (17.24) | 49.1 | (13.48) | 0.034 | * |

| Renter occupied | 61.9 | (17.24) | 50.9 | (13.48) | 0.034 | * |

| Income | ||||||

| Households by annual income (%) | ||||||

| <$25,000 | 38.2 | (12.04) | 40.0 | (15.69) | 0.662 | |

| $25,000–34,999 | 15.1 | (3.42) | 16.6 | (7.87) | 0.338 | |

| $35,000–49,999 | 17.6 | (4.30) | 15.6 | (3.73) | 0.133 | |

| $50,000–74,999 | 15.5 | (4.52) | 14.8 | (4.77) | 0.603 | |

| $75,000 and greater | 15.0 | (6.24) | 16.7 | (8.41) | 0.440 | |

| Average household income ($) | 44,440 | (8934.35) | 46,019 | (12,351.57) | 0.618 | |

| Median household income ($) | 32,967 | (7523.90) | 27,683 | (15,635.20) | 0.119 | |

| Food assets | ||||||

| Population density (n) | ||||||

| People per square mile | 7246.1 | (6795.20) | 4958.1 | (2431.00) | 0.180 | |

| Convenience stores (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 3.4 | (2.84) | 2.3 | (1.95) | 0.169 | |

| Total count per square mile | 2.3 | (2.23) | 1.1 | (1.07) | 0.061 | |

| Grocery stores (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 4.1 | (3.09) | 4.6 | (2.62) | 0.578 | |

| Total count per square mile | 3.3 | (4.40) | 2.0 | (1.24) | 0.293 | |

| Full service restaurants (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 14.6 | (12.30) | 14.7 | (10.77) | 0.988 | |

| Total count per square mile | 9.9 | (8.40) | 7.4 | (7.70) | 0.323 | |

| Fast food restaurants (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 6.2 | (5.97) | 4.7 | (4.84) | 0.407 | |

| Total count per square mile | 3.9 | (3.52) | 2.2 | (2.25) | 0.103 | |

| PA assets | ||||||

| Fitness clubs and recreational centers (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 0.6 | (1.21) | 0.5 | (0.99) | 0.903 | |

| Total count per square mile | 0.5 | (1.25) | 0.2 | (0.51) | 0.508 | |

| Park area (%) | ||||||

| Percent land area (square mile) covered by parks | 6.1 | (9.05) | 2.5 | (1.87) | 0.137 | |

Definitions and data sources are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (see online supplementary material at www.liebertpub.com/chi).

Student's t-test.

The number candidate schools attendance zones in each group.

p≤0.05; **p≤0.01.

TX CORD, The Texas Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration project; HS, high school; grad, graduate; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

For the comparisons between Austin and Houston attendance zones (notwithstanding catchment type), 22 of 47 separate variables showed statistically significant differences. These include the percentage of residents who were white non-Hispanic (p=0.019), black (p=0.004), and other race (American Indian, other race, or two or more races; p=0.001). In addition, the racial/ethnic minority population was 8.9% higher in Houston (p=0.029). There were 10.6% more residents in Houston with less than a high school education (p=0.007) and 7.9% fewer residents in Houston with some college or an associate's degree (p<0.001). All of the income variables were significantly different between the two cities. In addition, the density of convenience stores per square mile (p=0.0319), as well as the grocery store density per population (p=0.020) and per square mile (p=0.030), showed significant differences. The population distributions in age groups 0–4 years (p=0.016), 35–64 years (p=0.029), and greater than 65 years (p=0.019) were different between the two cities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparing TX CORD Candidate School Attendance Zones in Austin, Texas, with Those in Houston, Texasa

| Austin (n=23)b | Houston (n=25)b | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Total population | 137,924 | (2203.24) | 189,308 | (3664.70) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 22.2 | (14.75) | 11.8 | (14.87) | 0.019 | ** |

| Black | 13.8 | (13.18) | 34.5 | (29.75) | 0.004 | ** |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.7 | (1.07) | 2.0 | (2.21) | 0.610 | |

| Other race | 1.6 | (0.41) | 1.1 | (0.58) | 0.001 | ** |

| Hispanic origin (any race) | 52.3 | (19.77) | 47.6 | (29.57) | 0.526 | |

| Minority population | 79.0 | (12.41) | 87.9 | (14.83) | 0.029 | * |

| Age, years (%) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 9.6 | (1.95) | 8.0 | (2.45) | 0.016 | * |

| 5–19 | 21.2 | (4.64) | 20.8 | (4.10) | 0.725 | |

| 20–34 | 29.8 | (5.30) | 26.5 | (7.95) | 0.104 | |

| 35–64 | 32.5 | (3.08) | 35.1 | (4.52) | 0.029 | * |

| ≥65 | 6.9 | (3.01) | 9.7 | (4.65) | 0.019 | * |

| Gender distribution (%) | ||||||

| Male | 51.6 | (2.26) | 51.9 | (6.48) | 0.843 | |

| Female | 48.4 | (2.26) | 48.1 | (6.48) | 0.843 | |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Education of those over 25 (%) | ||||||

| Total population over 25 years | 92,577 | 129,743 | ||||

| <HS | 30.9 | (11.32) | 41.5 | (14.47) | 0.007 | ** |

| HS grad | 26.0 | (4.16) | 27.3 | (7.28) | 0.459 | |

| Some college and associates | 24.8 | (5.50) | 16.9 | (5.26) | 0.000 | ** |

| Bachelors or grad | 18.2 | (7.77) | 14.2 | (11.00) | 0.160 | |

| Gender distribution (%) | ||||||

| Male | 51.6 | (2.26) | 51.9 | (6.48) | 0.843 | |

| Female | 48.4 | (2.26) | 48.1 | (6.48) | 0.843 | |

| Household types (%) | ||||||

| Households with 1 person | 26.2 | (7.02) | 29.2 | (8.93) | 0.193 | |

| Households with 2+people | ||||||

| Family households | 83.9 | (7.32) | 88.0 | (6.05) | 0.039 | * |

| Both parents | 57.1 | (6.12) | 54.5 | (10.21) | 0.280 | |

| With own children | 52.9 | (10.22) | 46.9 | (11.41) | 0.061 | |

| Single parent | 42.9 | (6.12) | 45.5 | (10.24) | 0.284 | |

| With own children | 52.5 | (6.26) | 43.7 | (8.34) | 0.000 | ** |

| Nonfamily Households | 16.1 | (7.32) | 12.0 | (6.05) | 0.039 | * |

| Family household size (%) | ||||||

| ≤4 persons | 72.7 | (8.24) | 74.6 | (7.24) | 0.407 | |

| >4 persons | 27.3 | (8.24) | 25.4 | (7.24) | 0.407 | |

| Households by tenure (%) | ||||||

| Owner occupied | 40.6 | (13.04) | 42.4 | (19.92) | 0.702 | |

| Renter occupied | 59.4 | (13.04) | 57.6 | (19.92) | 0.702 | |

| Income | ||||||

| Households by annual income (%) | ||||||

| <$25,000 | 30.1 | (8.40) | 46.8 | (11.62) | 0.000 | ** |

| $25,000–34,999 | 17.1 | (6.67) | 14.1 | (2.72) | 0.043 | * |

| $35,000–49,999 | 19.4 | (3.81) | 14.7 | (3.20) | 0.000 | ** |

| $50,000–74,999 | 18.8 | (2.16) | 12.0 | (3.73) | 0.000 | ** |

| $75,000 and greater | 18.1 | (4.70) | 13.1 | (7.83) | 0.010 | ** |

| Average household income ($) | 48,894 | (6270.24) | 41,289 | (11,471.20) | 0.007 | ** |

| Median household income ($) | 34,910 | (11,880.80) | 28,009 | (8770.26) | 0.026 | * |

| Food assets | ||||||

| Population density (n) | ||||||

| People per square mile | 5322.6 | (2445.16) | 7880.5 | (7673.61) | 0.133 | |

| Convenience Stores (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 2.5 | (2.08) | 3.7 | (2.97) | 0.112 | |

| Total count per square mile | 1.3 | (1.30) | 2.5 | (2.36) | 0.032 | * |

| Grocery stores (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 3.3 | (2.32) | 5.2 | (3.17) | 0.020 | * |

| Total count per square mile | 1.7 | (1.20) | 4.0 | (4.83) | 0.030 | * |

| Full service restaurants (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 15.4 | (13.08) | 13.9 | (10.53) | 0.675 | |

| Total count per square mile | 8.0 | (6.64) | 10.2 | (9.40) | 0.347 | |

| Fast food restaurants (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 6.1 | (5.16) | 5.3 | (6.11) | 0.640 | |

| Total count per square mile | 3.1 | (2.84) | 3.5 | (3.63) | 0.673 | |

| PA assets | ||||||

| Fitness clubs and recreational centers (n) | ||||||

| Total count per 10,000 people | 0.5 | (1.23) | 0.6 | (1.07) | 0.936 | |

| Total count per square mile | 0.2 | (0.41) | 0.6 | (1.42) | 0.169 | |

| Park area (%) | ||||||

| Percent land area (square mile) covered by parks | 5.8 | (7.23) | 4.2 | (8.21) | 0.453 | |

Definitions and data sources are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (see online supplementary material at www.liebertpub.com/chi).

Student's t-test.

The number candidate schools attendance zones in each group.

p≤0.05; **p≤0.01.

TX CORD, The Texas Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration project; HS, high school; grad, graduate; PA, physical activity; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

GIS was used to describe and compare neighborhood-level characteristics in order to select comparable study areas for the TX-CORD project. There were minimal differences between the neighborhood characteristics of the intervention and comparison elementary school attendance zones. However, inherent differences between Houston and Austin were highlighted when the cities were compared on the selected variables. The cities have different race/ethnicity and income distributions as well as food and PA assets. The process used in selecting catchment areas in both cities minimized these differences across the intervention and comparison catchment areas.

The CORD project was required to study low-income, underserved populations, including children eligible for Medicaid. Not surprisingly, the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the catchment areas differed from the general profiles of Austin and Houston. When compared to the overall city of Austin, the Austin catchment areas have a larger Hispanic population, lower median household income, and lower home ownership rates. Also, the Houston catchment areas have had larger Hispanic and Black populations, lower median household income, and lower home ownership rates, when compared to the city of Houston. These differences are expected, given that we were attempting to target our programs to a Medicaid-eligible population within each city.

The GIS approaches that were used have several potentially significant implications for community health research and practice.

Analytical Procedures in Community Health Research

Specifically for obesity-focused community research, the assessment of demographic characteristics, SES, food assets, and PA assets provides relevant knowledge on the community-level attributes that are related to obesity, or to obesity-related behaviors. Consequently, in evaluating the impact of community-wide interventions (as is being done in the TX CORD), observed differences in these community-level attributes, using the described GIS approach, can be incorporated into the impact evaluation process through their use in analytical protocols as covariates.

Community Health Improvement through Practice

GIS approaches can provide robust and detailed area-level information on communities where practitioners work. Practitioners can use this information (e.g., those aggregated at the school attendance zone level) to analyze the population from which they draw students. For instance, identifying racial and ethnic backgrounds, along with other relevant SES information of communities from which students are drawn, may provide practitioners with the opportunity to employ culturally appropriate techniques or appropriately resourced curriculums in the delivery of health services. Likewise, community stakeholders, including residents and practitioners, can use this method to objectively identify the community-level characteristics of a particular area, and through that knowledge, be able to more appropriately address the needs within the population where health services are being provided.

Community Assessment and Engagement

Inherently, the GIS approaches that we undertook are a form of community assessment. The outcome of these approaches can be used to initiate an engaged and interactive forum for conversations with community stakeholders. For instance, practitioners (e.g., TX CORD project managers) can use the findings on food assets and PA assets for a particular community to enrich their conversations with partners and leaders in the community in order to help community stakeholders obtain resources. For example, a nonprofit that focuses on eliminating food deserts in the community can use food and PA analysis maps to identify high-risk, target areas that would benefit from their engagement and involvement. The spatial analyses provide information that promote efficient and effective use of funding. Community stakeholders may be able to channel community resources into initiatives that would have resulted from being furnished with such community assessment findings. Furthermore, the visual aspect of GIS also has many practical uses in public health, such as in translational and community-based participatory research. Mapping data can help generate hypotheses, identify patterns, and aid in communications with funders, participants, and the general public. In the same vein, the IOM has called for the use of more data “dashboards” and visual representation of information that can be interactive and display data in easily understood formats.35 Seeing where things are happening on the ground can be a powerful tool to enhance individual and collective understanding.

Some limitations of the current study include potential inaccuracies in the data used, having been derived from various secondary sources. Also, given that attendance zones are not consistent with standard census geography, data aggregated at that geographic unit are estimates derived from an interpolation process in the Business Analyst Suite (Esri) and may therefore be inaccurate, although the same process is used in other instances, across industry, and by various entities (government, industry, and academia). Nevertheless, elementary school catchment areas are more likely to be neighborhood based and are usually more homogeneous than middle or high school catchment areas. The unequal sample sizes between the intervention and comparison sites is noteworthy; as a potential source of confounding. However, the problem of unequal sample sizes may not matter under moderate degrees of imbalance,36 as is the case in the current analysis. Last, it is important to note that there could still be other factors, observed or unobserved, that could cause selection bias in the analysis, despite the procedures that we have reported on in the current work. This matching process greatly reduces the risk of blatant selection bias, but it does not eliminate the threat completely.

Conclusion

Neighborhood characteristics of the intervention and comparison catchment areas were comparable (based on elementary school attendance zones) on the majority of examined variables, and this reflects the effectiveness of the methodology that was used to demarcate the TX CORD catchment boundaries. The approaches employed highlight the usefulness of the GIS techniques in community health research and practice for obesity prevention studies. Future studies could expand on the current work by examining other PA asset variables (e.g., bike lanes and sidewalks) to provide for a more robust comparison of the neighborhood-level built environment asset in other project settings that are similar to the TX CORD. Last, we expect that future advances in the prevention of childhood obesity will benefit from the use of spatial analyses approaches that provide researchers with thematic understanding of the complex interactions of the environmental determinants of childhood obesity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by cooperative agreement RFA-DP-11-007 from the CDC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. Additional support was provided by the Michael and Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living. This work is a publication of the USDA (USDA/ARS) Children's Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, and had been funded, in part, with federal funds from the USDA/ARS under Cooperative Agreement No. 58-6250-0-008. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement from the U.S. government.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.McGuire S. Institute of Medicine. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: Solving the weight of the nation. National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock EP, O'Connor EA, Williams SB, et al. Effectiveness of weight management programs in children and adolescents AHRQ publication no. 08-E014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang TT, Drewnowski A, Kumanyika SK, et al. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: Solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q 2009;87:123–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape up Somerville first year results. Obesity 2007;15:1325–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoelscher DM, Springer AE, Ranjit N, et al. Reductions in child obesity among disadvantaged school children with community involvement: The Travis County CATCH Trial. Obesity 2010;18:S36–S44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanigorski AM, Bell AC, Kremer PJ, et al. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in children through community capacity-building: Results of a quasi-experimental intervention program, Be Active Eat Well. Int J Obes (Lond.) 2008;32:1060–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, Levy D, et al. Changing the future of obesity: Science, policy, and action. Lancet 2011;378:838–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blakely TA, Woodward AJ. Ecological effects in multi-level studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:367–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parmenter BM, McMillan T, Cubbin C, et al. Developing geospatial data management, recruitment, and analysis techniques for physical activity research. J Urban Reg Inf Syst Assoc 2008;20:13–19 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoelscher DM, Day RS, Lee ES, et al. Measuring the prevalence of overweight in Texas schoolchildren. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1002–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—Gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:6–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen I, Boyce WF, Simpson K, et al. Influence of individual-and area-level measures of socioeconomic status on obesity, unhealthy eating, and physical inactivity in Canadian adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee RE, Cubbin C. Neighborhood context and youth cardiovascular health behaviors. Am J Public Health 2002;92:428–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Poverty areas residence and changes in physical activity level: Evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1709–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman T, Cushing RA, Jackson RJ. Contributions of built environment to childhood obesity. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, et al. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: Associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:1823–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satia JA, Galanko JA, Siega-Riz AM. Eating at fast-food restaurants is associated with dietary intake, demographic, psychosocial and behavioural factors among African Americans in North Carolina. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:1089–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt M, Affenito SG, Striegel-Moore R, et al. Fast-food intake and diet quality in black and white girls: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute growth and health study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:626–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA Study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet 2005;365:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson OM, Ballew C, Resnicow K, et al. Food purchased away from home as a predictor of change in BMI z-score among girls. Int J Obes 2003;28:282–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reidpath DD, Burns C, Garrard J, et al. An ecological study of the relationship between social and environmental determinants of obesity. Health Place 2002;8:141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, et al. Associations of the local food environment with diet quality: A comparison of assessments based on surveys and Geographic Information Systems. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:917–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morland K, Wing S, Roux AD. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents' diets: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1761–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell LM, Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Availability of physical activity–related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: A national study. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1676–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davison KK, Lawson CT. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children's physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2006;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, et al. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics 2006;117:417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinrich KM, Lee RE, Suminski RR, et al. Associations between the built environment and physical activity in public housing residents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Census Bureau. ACS 2005–2009 (5-year estimates). Available at www.census.gov/acs/www Last accessed November12, 2011

- 31.Kelder SH. Dissemination of a coordinated school health program to meet Texas Senate Bill 19 requirements. Presented at the 131st Annual Meeting; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrow JR, Jr., Martin SB, Welk GJ, et al. Overview of the Texas Youth Fitness Study. Res Q Exerc Sport 2010;81:S1–S5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corbin CB, Pangrazi RP. FITNESGRAM/ACTIVITYGRAM: An introduction. In: Welk GJ, Meredith MD. (eds), FITNESSGRAM® /ACTIVITYGRAM® Reference Guide. The Cooper Institute: Dallas, TX, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States Census Bureau. 2010 Census. U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Available at www.census.gov/2010census/data Last accessed February15, 2013

- 35.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Evaluating Obesity Prevention Efforts: A Plan for Measuring Progress. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Belle G. Statistical Rules Of Thumb, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2008 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.