Abstract

Calciphylaxis is a rare but devastating condition that has continued to challenge the medical community since its early descriptions in the scientific literature many decades ago. It is predominantly seen in chronic kidney failure patients treated with dialysis (uremic calciphylaxis) but is also described in patients with earlier stages of chronic kidney disease and with normal renal function. In this In Practice feature, we review the available medical literature regarding risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of both uremic and non-uremic calciphylaxis. High quality evidence for the evaluation and management of calciphylaxis is lacking at this time due to its rare incidence, poorly understood pathogenesis, and the relative paucity of collaborative research efforts. We hereby provide a summary of recommendations developed by the Massachusetts General Hospital's Multi-disciplinary Calciphylaxis Team for calciphylaxis patients.

Keywords: Calcific uremic arteriolopathy, calciphylaxis, risk factors, sodium thiosulfate, warfarin

Introduction

Calciphylaxis is a rare and highly morbid condition that has continued to challenge the medical community since its early descriptions.1-4 Calciphylaxis predominantly affects chronic kidney failure patients treated by dialysis.5,6 However, calciphylaxis is not limited to patients treated by dialysis and also occurs in patients with normal kidney function and in those with earlier stages of chronic kidney disease (referred to as non-uremic calciphylaxis).7-10 Both uremic and non-uremic calciphylaxis are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The morbidity is related to severe pain, non-healing wounds, recurrent hospitalizations, and to adverse effects of treatments. The one-year mortality in calciphylaxis patients is reported at 45-80% with ulcerated lesions associated with higher mortality compared to non-ulcerated lesions and sepsis being the leading cause of death.11-13 Mortality rates in chronic hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis were almost 3 times higher than for chronic hemodialysis patients without calciphylaxis in the United States Renal Data System.14 Some studies also report that the incidence of calciphylaxis is increasing in dialysis population; however, whether this is truly an increase in incidence or enhanced awareness remains unclear.11,14,15

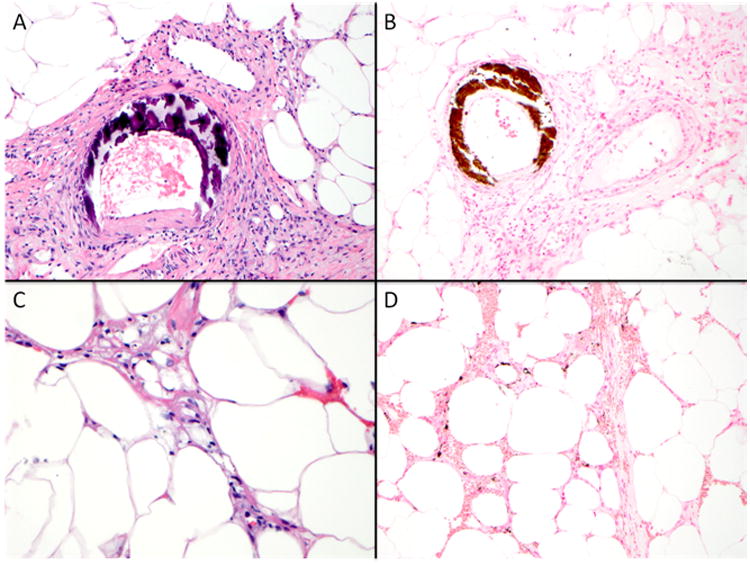

Calciphylaxis clinically presents with severe painful skin lesions (livedo reticularis, reticulate purpura, violaceous plaques, or indurated nodules) that demonstrate poor healing and are frequently complicated by blistering and ulcerations with superimposed infections (Figure 1).7,16,17 Ulcerated lesions commonly demonstrate black eschar. Although, skin manifestations dominate the clinical presentation, patients have been reported to have vascular calcifications in skeletal muscle, brain, lungs, intestines, eyes, and mesentery.18-24 In this regard, calciphylaxis can be considered as a continuum of a systemic process leading to arterial calcification in many vascular beds.25 Histologically, calciphylaxis is characterized by calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia of small dermal and subcutaneous arteries and arterioles leading to ischemia and intense septal panniculitis (Figure 2).26-28 Calcification most commonly involves the medial layer of small arteries and arterioles; however, involvement of the intimal layer and the interstitium of subcutaneous adipose tissue has been reported.17 Calcification is considered to be an early and essential process in calciphylaxis plaque development and it is hypothesized that the vascular calcification leads to vascular endothelial dysfunction and injury.29-31 Despite the well characterized clinical and histological descriptions of calciphylaxis, its exact pathogenesis remains unclear and there is limited data regarding the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for this devastating condition.

Figure 1. Morphology of calciphylaxis lesions.

Figure 2. Histopathology of calciphylaxis.

Course basophilic medial calcification of small arteries as demonstrated by Hematoxylin & Eosin stain (400×) and highlighted by von Kossa histochemical stain (200×) (Panel A-B). Septal panniculitis and subcutaneous fat necrosis with presence of subtle finely granular basophilic calcium deposits (400×, Hematoxylin & Eosin, Panel C). A von Kossa histochemical stain aids in the detection of interstitial calcium deposits, which may not be identified on routine histologic sections (200×, Panel D).

In this In Practice feature, we review the available medical literature regarding risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of calciphylaxis. We would like to stress upon the readers that the rare incidence of calciphylaxis combined with its poorly understood pathogenesis, and relative paucity of collaborative research efforts have imposed significant limitations for development of high quality evidence for calciphylaxis. We provide a summary of recommendations to evaluate and manage calciphylaxis patients developed by the Massachusetts General Hospital's Multi-disciplinary Calciphylaxis Team. The molecular basis of vascular calcification and hypotheses for calciphylaxis pathogenesis are outside the scope of this review and we refer the readers to excellent articles on this topic by Dr. Weenig,32 Dr. Hayden,33 and Dr. Moe.25

Historical Perspectives and Terminology

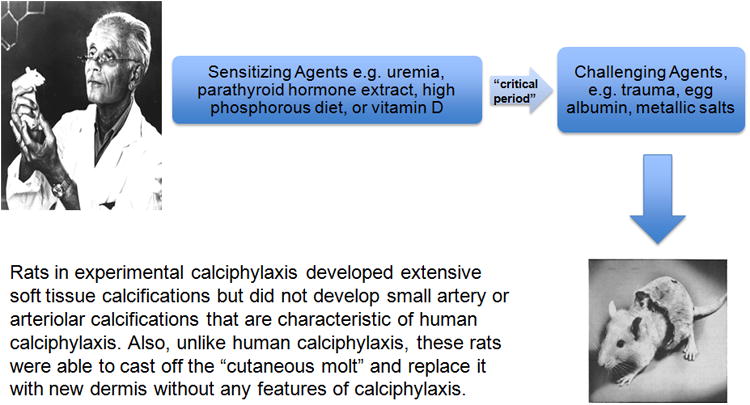

Professor Hans Selye and his colleagues coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961.1,34-36 Selye conducted laboratory experiments in rats to induce generalized subcutaneous soft tissue calcification by applying a 2-step process interrupted by a “critical time” period: 1) “Sensitization” by agents such as parathyroid extract, high dose vitamin D, high phosphorous diet, or induction of renal failure followed by, 2) Application of a “challenging agent” such as local trauma, egg albumin, or metallic salts (Figure 3). Development of cutaneous calcification in this animal model was thought to be an adaptive or phylactic reaction and was referred to as calciphylaxis (portmanteau of calcification and phylaxis).

Figure 3. Professor Selye's experimental calciphylaxis model.

Within a few years after these experimental descriptions of calciphylaxis by Selye, 2 case reports were published that described patients with renal failure who developed widespread subcutaneous calcifications.2,4 The presence of renal failure leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism was considered as a “sensitizing agent” by authors of these reports and they speculated that iron therapy or local trauma may have served as “challenging agents.” The authors astutely drew parallels between these human presentations and Selye's experimental model, and diagnosed these patients as having calciphylaxis. Subsequent reports of a similar nature in the medical literature used the term calciphylaxis, a practice that continues even today.

It is important to understand the key differences between experimental calciphylaxis in Selye's experimental model and human calciphylaxis. First and foremost, the animals in experimental calciphylaxis did not develop small artery or arteriolar calcifications although extensive soft tissue calcifications were present. Secondly, the animals in experimental calciphylaxis were able to cast off the calcified skin molt and replace it with new dermis that did not have any features of calciphylaxis (Figure 3). Thirdly, experimental calciphylaxis was prevented by administration of glucocorticosteroids, a fact that contradicts the available data in human calciphylaxis.9,12,37

The differences between experimental calciphylaxis and human calciphylaxis, as well as a widely accepted recognition that calciphylaxis is not a hypersensitivity reaction, has led some authors to propose descriptive terms such as calcific uremic arteriolopathy for human calciphylaxis.17,38,39 Although descriptive terms incorporate pathological implications in a truer sense than calciphylaxis, it is important to take into account the ubiquitous use of calciphylaxis term in the medical community. Thus, our preference is to use the term calciphylaxis when referring to calciphylaxis patients on dialysis and non-uremic calciphylaxis to refer to patients with normal kidney function and those with earlier stages of CKD.9

Risk Factors

Many case reports, case series, and observational studies have been published to understand risk-associations for calciphylaxis and in recent years there has been a significant increase in publications on calciphylaxis (Figure S1). Table 1 provides a summary of case-control studies conducted to understand the risk factors for calciphylaxis. It is important to recognize that the study populations in terms of case and control definitions have been heterogeneous and these studies suffer from limitations of small sample size, single center experience, and selection bias. Furthermore, like any other epidemiological study, these investigations do not determine causality.

Table 1. Summary of case-control studies evaluating risk factors for uremic calciphylaxis.

| study | population | Main findings | comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigwekar et al15 | Cases: n=62; 100% on hemodialysis; biopsy confirmation in 100%; all cases were hospitalized at the time of calciphylaxis diagnosis Controls: n=124, hospitalized hemodialysis patients matched for gender and timing of hospitalization |

|

|

| Weenig et al12 | Cases: n=49; 84% on hemodialysis and 16% on peritoneal dialysis; biopsy confirmation in 86% Controls: n=98, matched for age and gender |

|

|

| Fine et al11 | Cases: n=36; 78% on peritoneal dialysis and 22% on hemodialysis; biopsy confirmation in 11% Controls: n=72, matched for duration of dialysis |

|

|

| Hayashi et al59 | Cases: n=28; 100% on hemodialysis; unclear in how many cases biopsy confirmation was obtained Controls: n=56, matched for age and duration of dialysis |

|

|

| Mazhar et al58 | Cases: n=19; 95% on hemodialysis and one patient had a functioning renal allograft; biopsy confirmation in 84% Controls: n=54, matched for the date of initiation of hemodialysis |

|

|

| Ahmed et al46 | Cases: n=10; 80% on hemodialysis, 20% on peritoneal dialysis; biopsy confirmation in 100% Controls: n=180, dialysis patients |

|

|

| Angelis et al56 | Cases: n=10; 100% on hemodialysis; unclear in how many cases biopsy confirmation was obtained Controls: n=232, chronic hemodialysis patients from the same center |

|

|

| Bleyer et al41 | Cases: n=9; 67% on hemodialysis and 22% on peritoneal dialysis; biopsy confirmation in 100% Controls: n=347, chronic hemodialysis patients from the same center |

|

|

| Zacharias et al60 | Cases: n=8; 100% on peritoneal dialysis; biopsy confirmation in 12.5 % Controls: n=37, matched for dialysis modality and length of time on dialysis |

|

|

Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral Bone Disease (CKD-MBD) axis abnormalities

Hyperphosphatemia, elevated calcium phosphorous product, hypocalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, and vitamin D deficiency are prevalent in dialysis patients.40 Calciphylaxis has been traditionally considered as a manifestation of severely dysregulated calcium-phosphorous metabolism in dialysis patients due to the high prevalence of mineral bone abnormalities, the frequent use of pro-calcification treatments (such as calcium salts and vitamin D), and the original description of parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D as sensitizing agents in Selye's model.39 However, it is important to take into account that despite the high prevalence of mineral bone abnormalities in dialysis patients, calciphylaxis is a rare disease and a number of reports in the literature describe dialysis patients who developed calciphylaxis despite the absence of significant mineral bone laboratory abnormalities.5,41 Relatively normal or even low serum calcium and serum phosphorous levels are possible at the time of calciphylaxis diagnosis due to tissue deposition of these divalent ions underlining the importance of longitudinal data review.31,42 Furthermore, serum parathyroid hormone levels below 100 pg/mL may be indicative of adynamic bone disease, an independent risk factor for vascular calcification.43

In our opinion, although the role of dysregulated calcium- phosphorous metabolism as a risk factor for calciphylaxis cannot be overlooked and requires further investigation in larger observation studies, it is not the sole risk factor for calciphylaxis.

Demographic factors

Calciphylaxis is most commonly reported in patients in the 5th decade of life; however it has also been described in patients significantly younger including children.44,45 Calciphylaxis is more commonly seen in women compared to men with a 2:1 female predominance.12,15,46 Calciphylaxis in our experience and as reported in the literature is also more common in whites compared to non-whites.12,15,41,46 The biological explanation for these observations is unclear.

Co-morbid conditions

Diabetes mellitus is a frequently reported co-morbidity in patients with calciphylaxis.11,47 However, no data are available regarding whether diabetes control or duration affects calciphylaxis risk.

Obesity is reported as a risk factor for proximal calciphylaxis (involving trunk, thighs, breasts, etc); although reasons for predilection for adipose tissue involvement remain speculative.41 The fibroelastic septa that anchor the skin to the body provide scaffolding for dermal arterioles. Obesity, due to expansion of the subcutaneous compartment by adipose tissue, subjects these septa and arterioles to increased tensile stress, further reducing the blood flow in already calcified arterioles in dialysis patients.31 Whether obesity is a risk factor for distal calciphylaxis (e.g. forearms, hands, feet, etc.) remains unknown.

Calciphylaxis has been reported in patients with autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome, temporal arteritis, and rheumatoid arthritis raising the possibility of a potential role for autoimmunity in its development.48 Furthermore, treatments used to manage autoimmune conditions such as corticosteroids, methotrexate, and ultraviolet light have been implicated as potential triggers for calciphylaxis.48,49

Hypercoagulable conditions may predispose patients to calciphylaxis. There are case reports of calciphylaxis in patients with both hereditary and acquired thrombophilic conditions such as protein C and protein S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, cryofibrinogenemia, and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome.50-53 However, arguments against the potential causative role of hypercoagulable conditions have also been made. In a case control study of 49 uremic calciphylaxis patients and 98 control patients on dialysis, no significant difference between cases and controls for protein C activity, protein S antigen, or antithrombin III activity were noted.12 Thrombi formation in venules that are frequently noted in patients with thrombophilic conditions are not seen in calciphylaxis patients.54 Despite these arguments, evaluation for thrombophilic conditions in calciphylaxis patients should be considered since it has important treatment implications.

Infectious, autoimmune, and alcoholic hepatitis have been reported as risk factors for calciphylaxis.12,55 Calciphylaxis in the setting of liver disease is thought to be mediated via either inflammation or acquired thrombophilia from protein C or protein S deficiency.

Longer dialysis vintage of over 6-7 years has been reported as a risk factor for calciphylaxis.56 However, like most risk factors associated with calciphylaxis, this relationship has been inconsistent across studies and there are reports in the literature of patients with significantly shorter dialysis vintage developing calciphylaxis.15,57 In a large cohort of uremic calciphylaxis patients, median dialysis vintage was 3.1 years.47

Hypoalbuminemia in dialysis patients can result from a variety of conditions including poor nutrition and inflammation. Multiple case-control studies report lower albumin levels in calciphylaxis patients when compared to dialysis patients without calciphylaxis.15,41,58,59 However, methodological limitations of these studies restrict conclusions regarding whether hypoalbuminemia is pathogenic, or whether it is merely a marker of malnutrition or chronic inflammation, or whether it is a result of calciphylaxis itself.

Medications

Calcium supplements, calcium-based phosphate binders, active vitamin D, warfarin, corticosteroids, iron therapy, and trauma related to subcutaneous insulin or heparin injections have been associated with increased calciphylaxis risk.11,12,15,59-62

Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, has been used for many years as an anticoagulant due to its properties to inhibit the carboxylation and activation of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. Recent reports indicate that endogenous inhibitors of vascular calcification such as Matrix Gla Protein are also vitamin K-dependent for their activation.63 Patients on warfarin therapy may not be able to inhibit vascular calcification due to a reduction in the active forms of these proteins. The studies investigating the association of warfarin use and calciphylaxis suffer from the same methodological limitations as those described above for other risk factors and have been inconsistent. However, the warfarin-calciphylaxis association is intriguing as it provides a unique opportunity to understand the biological role of vitamin K in calciphylaxis. A pilot clinical trial to investigate the role of vitamin K in calciphylaxis is currently underway (NCT02278692).

Diagnosis and Evaluation

A high index of clinical suspicion is required for early and accurate diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Table 2 provides a summary of clinical mimics of calciphylaxis.

Table 2. Clinical mimics of calciphylaxis.

| Features of clinical mimic | Features of calciphylaxis | |

|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerotic vascular disease | Symptoms of claudication, weak peripheral pulses, distal distribution, abnormal ankle-brachial index | Can be proximal or distal distribution, severe pain, dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy |

| Cholesterol embolization | Usually in acral distribution, may have features associated with renal or gastrointestinal ischemia, cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy | Can be proximal or distal distribution, dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy |

| Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis | Brawny plaques, thickened skin, history of exposure to gadolinium, moderate intensity pain, marked increase in spindle cells and fibrosis on skin biopsy | Severe pain, dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy |

| Oxalate vasculopathy | Acral distribution, history of calcium oxalate stones, birefringent, yellowish-brown, polarizable crystalline material deposition in the dermis and arteriolar wall on skin biopsy | Can be proximal or distal distribution, calcium deposits non-polarizable |

| Purpura fulminans | Usually seen in the settings such as septic shock or disseminated intravascular coagulation, diffuse body distribution, rapid progression, clinical features of shock | Unlikely to have diffuse whole body distribution, absence of serological features of disseminated intravascular coagulation, dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy |

| Vasculitis | Systemic features of vasculitis, serological test abnormalities (e.g. cryoglobulins), no dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy, unlikely to have full-thickness necrosis or large areas of involvement | Absence of systemic features and serological abnormalities of vasculitis (unless autoimmune disease is a trigger for calciphylaxis), black eschar, dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy |

| Warfarin necrosis | Typically seen within the first 10 days of warfarin initiation, manifestation of paradoxical hypercoagulable state created by a transient imbalance in the procoagulant and anticoagulant pathways warfarin discontinuation associated with clinical improvement in majority of cases | Warfarin exposure of prolonged duration when calciphylaxis associated with warfarin therapy, black eschar, dermal arteriolar calcification on skin biopsy |

Clinical Features

Clinical characteristics of calciphylaxis skin lesions can be variable (Figure 1). Intense pain associated with cutaneous lesions and palpation of firm calcified subcutaneous tissue is suggestive of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients and in patients with other risk factors for calciphylaxis.16,17

A detailed history focused on the proposed risk factors should be obtained. A thorough physical examination should be performed to identify additional skin lesions. In patients on warfarin therapy, distinction should be made between warfarin necrosis and calciphylaxis (Table 2). 64

Skin biopsy

Definitive diagnosis of calciphylaxis requires a skin biopsy and should be considered whenever the calciphylaxis diagnosis is entertained. The following issues related to skin biopsy need attention: 1) Discussion of risks and benefits of skin biopsy is essential. Possible risks include ulceration, superimposed infection, propagation of new lesions, bleeding, and induction of necrosis. Benefits include exclusion of other conditions that can mimic calciphylaxis (Table 2),17 2) In the hands of an experienced dermatologist or surgeon the potential yield can be maximized, 3) A punch or telescoping biopsy (4-5 mm deep) from the lesion margin or deep incisional wedge skin biopsy are likely to have the best yield.65 In our experience, a punch biopsy is safer and is a preferred approach over an incisional biopsy. In general, biopsy at the center of the ulcer or of necrotic area is of low diagnostic yield.

The characteristic histological features of calciphylaxis include calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia of small dermal and subcutaneous arteries and arterioles leading to cutaneous ischemia and intense septal panniculitis (Figure 2).26-28 Detection of micro-calcification often requires special stains such as von Kossa or Alizarin red. Performing both von Kossa and Alizarin red stains may increase the detection of calcium deposits over individual stain alone and should be considered when the clinical suspicion is high but calcium deposits are not readily apparent on routine histological sections.28 The exact sequence of events in calciphylaxis pathogenesis remains to be determined but the arteriolar calcification is likely the first event, followed by thrombosis, and skin ischemia.29,30

Radiological tests and biomarkers

Non-invasive imaging tools (e.g. plain X-rays, nuclear bone scans) and circulating fetuin A levels have been reported to aid in the diagnosis of calciphylaxis.66-69 However, none of these tools have been systematically evaluated and are not recommended for clinical use at this time.

Laboratory evaluation

Laboratory evaluation should be conducted to further evaluate potential risk factors: 1) Renal function evaluation- serum blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (urinalysis, urine protein: creatinine ratio, and 24 hour urine collection for creatinine clearance to be considered for non-dialysis patients), 2) Mineral bone parameters evaluation- serum calcium, phosphorous, alkaline phosphatase, intact parathyroid hormone, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 3) Liver evaluation-serum transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and albumin, 4) Infection evaluation-complete blood count with differential (in all cases), and blood cultures (if leukocytosis or fever present), 5) Coagulation evaluation- prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, and partial thromboplastin time, 6) Inflammation evaluation- serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein and albumin, 7) Hypercoagulation evaluation- protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, and antiphospholipid antibody, and 8) Evaluation for autoimmune disease and malignancy as guided by the clinical suspicion.

Treatment

In our experience, a multi-disciplinary and multi-interventional approach involving input from the following disciplines is important: nephrology, dermatology, dermatopathology, wound or burn center, nutrition, and pain management. Input should be obtained as soon as the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is suspected to formulate a comprehensive and consistent management plan.

Multiple interventions have been described in the management of calciphylaxis;70 however, the overall quality of evidence is poor and data mostly come from retrospective cohort studies, case series, and case reports. At present, there is no published data from a randomized controlled trial that addresses any of the proposed interventions. Treatment recommendations are largely an expert opinion based on the clinical experience and available observational published data. A summary of our approach to calciphylaxis treatment is provided in Box 1 and is described below.

Box 1. Summary of treatment approach for uremic calciphylaxis.

Wound management

-Wound care team should be involved for recommendations regarding selection of dressings, chemical debriding agents, frequency of dressing changes, and negative pressure wound therapy.

-Surgical wound debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

-Hyperbaric oxygen therapy can be considered as a second line treatment if wounds not improving. Claustrophobia, access to treatment, and cost can be significant limiting factors of this therapy.70

-Antibiotic administration should be guided by clinical appearance of lesions and accompanying systemic features.

Pain management

-Often narcotic analgesics are required to control severe pain associated with calciphylaxis.

-Fentanyl may be preferred over morphine to minimize potential hypotension episodes associated with morphine.131

Sodium thiosulfate

-Intravenous sodium thiosulfate at doses ranging from 12.5 to 25 grams in the last 30 minutes of each hemodialysis session for patients on 3 times a week dialysis schedule.47 For patients with other hemodialysis prescriptions dose adjustments are needed according to published algorithms.114

-Nausea, metabolic acidosis, hypotension, and volume overload are potential adverse effects.47,70

-Intra-lesional sodium thiosulfate has been described to aid in the resolution of calciphylaxis lesions.117

Management of mineral bone disease

-Serum calcium and phosphorous levels should be maintained in the normal range and serum parathyroid hormone level should be maintained between 150-300 ng/mL.

-Calcium supplements, high dialysate calcium bath, vitamin D preparations should be avoided and instead cinacalcet to be considered to treat secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with calciphylaxis. Surgical parathyroidectomy is indicated in patients with refractory hyperparathyroidism.

-Excessive suppression of parathyroid hormone should be avoided.99

Dialysis prescription

Nutrition management

-Nutrition consult to address protein energy malnutrition should be obtained.

Management of other risk factors

-Risk vs. benefit discussion is needed to decide whether to continue warfarin and iron compounds in patients with calciphylaxis

Wound management

Wound or burn center and dermatology teams should be consulted for recommendations regarding dressings and need for surgical debridement.71,72 The goals of wound care are to control exudate, prevent infection, facilitate wound healing, and to keep the wound bed free of necrosed devitalized tissue.

Surgical wound debridement is a controversial procedure for calciphylaxis.72,73 In our experience, surgical debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis as evidence suggest wounds with non-infected, stable, and dry eschar with limited tissue involvement are better managed with chemical debridement than surgical debridement.74,75 The aim of surgical debridement involves removal of necrosed tissue (without interfering with the adjacent healthy tissue) to facilitate wound healing. This is best achieved by surgeons who are highly experienced in managing complex wounds. A retrospective analysis of 63 calciphylaxis cases from Mayo Clinic showed a 1-year survival rate of 61.6% for patients who underwent surgical debridement compared to 27.4% for those who did not, though the patients were not matched for disease severity or systemic illness.12 Deep ulcer shaving combined with split-thickness skin transplantation has been described in the management of distal calciphylaxis.76

Considering that the primary cause of mortality is sepsis, infected calciphylaxis lesions may require surgical debridement. Typically, serial wound debridement combined with negative pressure wound therapy to facilitate healthy granulation bed formation that can then be closed with a split thickness skin graft is what we consider at our center. Back grafting of the donor site with widely meshed skin (4:1) as described for burn management may facilitate donor site healing and prevent Koebner response at donor sites.77 The surgical debridement of necrotic eschar caused by calciphylaxis, when not infected, often depends on the involved tissue burden. Large necrotic areas may not heal with conservative treatment and may present a higher infectious risk.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been proposed in calciphylaxis wound management.78-80 In our experience, claustrophobia, access to treatment, and cost can be significant limiting factors for hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and we recommend this as a second line therapy to facilitate healing of recalcitrant calciphylaxis wounds.70 Sterile maggot therapy with larvae of the greenbottle fly, Lucilia sericata, has also been described as a second line therapy for calciphylaxis but experience is limited to case reports.81,82

Although antibiotics are not routinely indicated in calciphylaxis, we recommend a low threshold for antibiotic initiation, as guided by the clinical appearance of lesions and accompanying systemic features.

Pain management

Pain management is one of the most challenging aspects of calciphylaxis and many patients report severe pain despite administration of potent analgesics.83 The exact etiology of pain is unclear and is thought to be ischemic in origin but there may be a neuropathic component associated with nerve inflammation.84 Opioid analgesics are typically required to control severe pain, but morphine, codeine, and hydrocodone should be avoided in dialysis patients due to accumulation of neurotoxic metabolites.85,86 Oxycodone and hydromorphone can be used in patients with renal insufficiency but require close monitoring for side effects.85,86 Limited experience suggests multimodal analgesia combining opioids with non-opioid adjuvants, such as neuropathic agents, and ketamine, may improve symptomatic management of calciphylaxis.84 Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be limited in patients with renal dysfunction. Because of severity, and complexity of pain in this population, pain medicine and palliative care teams play a critical role in calciphylaxis management.

Modification of risk factors

CKD-MBD axis abnormalities

In our opinion, serum calcium and phosphorous levels should be maintained in the normal range and serum parathyroid hormone level should be maintained between 150-300 ng/mL. Calcium supplements and high dialysate calcium bath should be avoided and limited evidence supports administration of non-calcium based binders over calcium-based binders for management of hyperphosphatemia in patients with calciphylaxis.60,87-90 Cinacalcet is preferred to treat secondary hyperparathyroidism over vitamin D analogues in patients with calciphylaxis who have hypercalcemia and/or hyperphosphatemia.91-93 In the Evaluation of Cinacalcet Hydrochloride Therapy to Lower Cardiovascular Events (EVOLVE) trial that randomized 3,883 dialysis patients to either cinacalcet or placebo, a reduced risk of calciphylaxis was observed in the cinacalcet arm (6 vs. 18 events, P=0.009);94 however, the low event rate limits ability to draw conclusions regarding cinacalcet's benefit. Furthermore, whether cinacalcet treatment after calciphylaxis diagnosis alters the disease course remains unclear. We prefer cinacalcet over surgical parathyroidectomy considering potential risks of surgical wound infection, hungry bone syndrome, and adynamic bone disease associated with surgical parathyroidectomy.95 Furthermore, data on survival after surgical parathyroidectomy in calciphylaxis patients are retrospective and inconclusive.96-98 In all cases of calciphylaxis, excessive suppression of parathyroid hormone especially below 100 ng/mL should be avoided.99

Management of other risk factors

At present there are limited to no data to support whether discontinuation or minimization of potential triggers such as warfarin, trauma related to subcutaneous injections (e.g. insulin), and iron compounds leads to improvement in calciphylaxis outcomes.47 However, considering the morbidity and mortality associated with calciphylaxis and available epidemiological data that link these factors to calciphylaxis development, we recommend careful risk-benefit analyses for continuing therapies such as warfarin and iron. Particularly regarding warfarin, since alternate anticoagulation options are highly limited in dialysis patients, the decision regarding warfarin is not an easy one when a hypercoagulable condition is identified as a calciphylaxis risk factor or when the patient has other indications for anticoagulation. For insulin or subcutaneous heparin injections, rotating injection sites and avoiding trauma at lesion sites is recommended. For patients who are on immunosuppressive therapies that delay wound healing, appropriate alternate immunosuppressive agents that do not affect wound healing should be used.

Dialysis modality and dialysis prescription

Dialysis prescription should be optimized to achieve the recommended K/DOQI goals of dialysis adequacy.100 Intensifying dialysis by increasing duration or frequency has been described.71 In the absence of confirmatory data to support, we do not routinely recommend intensification of dialysis beyond the goals of dialysis adequacy.

In the literature, peritoneal dialysis is described to confer higher calciphylaxis risk when compared to hemodialysis;11,101 however, experience at our center is not consistent with this observation and we do not routinely transition patients from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis for calciphylaxis management.

Nutrition management

We recommend a nutrition consult to address malnutrition that is frequently present in calciphylaxis patients. If patients are not able to improve dietary intake then consideration should be given to nutrition via gastric tube and parenteral nutrition;54,102 however, evidence to support these interventions is lacking.

Sodium thiosulfate

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate is probably the most common intervention used to treat calciphylaxis (off-label indication).47,75,103-105 It is a reducing agent that forms water-soluble complexes with many metals and minerals. Its use in calciphylaxis was first reported over 10 years ago in a case report.106 However, there is no prospective trial data on this agent.

We conducted a multi-center retrospective cohort study on this topic in collaboration with the investigators from Fresenius Medical Care North America. We systematically evaluated the safety of intravenous sodium thiosulfate in 172 hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis.47 Data regarding effects on calciphylaxis lesions were obtained by surveying clinicians managing these patients and were available for 53 patients. Sodium thiosulfate was most frequently administered as 25 g intravenously in 100 ml of normal saline given over the last half-hour of each hemodialysis session and this is the currently recommended dose for an average 70 kg person who is on three times a week hemodialysis. Overall, intravenous sodium thiosulfate was well tolerated in this study. Notable side effects include nausea, vomiting, metabolic acidosis, hypotension, and volume overload.47,107-109 These side effects sometimes warrant dose modification or discontinuation. In our study, among surveyed patients, calciphylaxis improved in over 70% of patients (resolution or improvement); however, survey bias and other limitations of any retrospective study of this nature need to be acknowledged and at present, the best conclusion regarding sodium thiosulfate efficacy is that it remains unclear.110 This is further complicated by an elusive mechanism of action of sodium thiosulfate as recent investigations question the previously believed calcium-chelating properties of sodium thiosulfate and instead point toward direct vascular calcification inhibitory effects, antioxidant, and vasodilatory properties.111-113 It is also unclear what the optimal duration of sodium thiosulfate treatment is. In our experience, improvement in pain within 1-2 weeks after initiation of sodium thiosulfate is an important predictor of long-term response.

A few additional issues regarding sodium thiosulfate deserve mention. First, its dose needs adjustment if the patient is on more frequent dialysis or on continuous renal replacement therapies (Table 2).114 For patients who weigh less than 60 kg, we suggest reducing the dose to 12.5 gram to reduce the incidence of adverse events. Intra-peritoneal administration of sodium thiosulfate should be avoided due to risks of chemical peritonitis.115,116 Intra-lesional sodium thiosulfate has also been described to aid in the resolution of calciphylaxis lesions.117

Other treatments

A number of other treatments have been described in case reports and small case series that may have a potential role in the treatment of calciphylaxis. These include bisphosphonates, low-dose tissue plasminogen activator infusion, LDL-apheresis, vitamin K, and kidney transplantation.51,118-125 In our opinion, these modalities may be considered on a case-by-case basis taking into account the cost, availability, and patient-related factors with clear understanding of the limitations of the available data.

Non-uremic calciphylaxis

In a systematic review of 36 non-uremic calciphylaxis cases, primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancies, autoimmune disease, diabetes mellitus, and alcoholic liver disease were the most notable associated co-morbidities.9 Although none of the patients in this review had chronic renal failure requiring dialysis, reported renal function varied with 42% of patients with serum creatinine ≤1.2 mg/dL, 6 % with serum creatinine 1.3-1.5 mg/dL, 14% with 1.6-2.5 mg/dL, and 8% with 2.6-3.0 mg/dL. In 30% of the cases, authors did not report serum creatinine. In this systematic review, warfarin and corticosteroid use was present in 25% and 61% of cases respectively. In addition, case reports describe non-uremic calciphylaxis as a complication of Hodgkin's lymphoma, teriparatide therapy, gastric bypass surgery, and hypoparathyroidism.10,37,126-128

Skin lesions of non-uremic calciphylaxis have similar morphology as uremic calciphylaxis and have been described in both proximal and distal distributions. Same diagnostic and evaluation considerations discussed for uremic calciphylaxis apply to non-uremic calciphylaxis.

Data on treatment of non-uremic calciphylaxis are very limited. Successful resolution of non-uremic calciphylaxis with intravenous and intra-lesional sodium thiosulfate and bisphosphonate has been described.117,129,130 At our center, we treat non-uremic calciphylaxis patients with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 12.5 or 25 grams administered 4 to 5 days of the week in isolation or in conjunction with weekly intralesional sodium thiosulfate. The optimal treatment duration remains unclear.

Case resolution

The patient described at the beginning of this article underwent a systematic assessment for calciphylaxis risk factors. The potential risk factors were female gender, diabetes mellitus, long dialysis vintage, and low serum albumin. She was seen by a multi-disciplinary calciphylaxis team and underwent aggressive wound care, pain management, treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and optimization of her nutrition status. She had initial improvement in calciphylaxis lesions over the first 3 months but subsequently developed new ulcerated calciphylaxis lesions and died from septic shock.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Number of publications in PubMed on calciphylaxis or calcific uremic arteriolopathy between 1961 and 2013

Table 3. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate dosing recommendations based on pharmacokinetic simulations (adapted from Singh et al114).

| Number of hemodialysis sessions per week | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | Continuous renal replacement therapy | Continuous renal replacement therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood flow rate (ml/min) | 400 | 250 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 100 | 100 |

| Dialysis flow rate (ml/min) | 800 | 500 | 800 | 800 | 800 | 800 | 35 | 50 |

| Hemodialysis session duration (hours) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2.5 | 8 | 2 | Continuous | Continuous |

| Sodium thiosulfate dose per hemodialysis session (g) | 25 | 24 | 22 | 18 | 24 | 16 | 24, daily | 35, daily |

| Weekly sodium thiosulfate dose (g) | 75 | 72 | 88 | 90 | 120 | 96 | 168 | 245 |

Case presentation.

A 62-year-old obese Caucasian woman is evaluated for an extremely tender right thigh skin lesion. She has a long-standing history of end-stage renal disease from uncontrolled diabetes mellitus requiring chronic hemodialysis. A skin biopsy demonstrated dermal arteriolar calcification and mural thrombosis associated with septal panniculitis consistent with a diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Her laboratory data are as follows: serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), 160 pg/mL (160 ng/L); serum calcium, 8.1 mg/dL (2.03 mmol/L); serum phosphorus, 3.9 mg/dL (1.26 mmol/L); serum albumin, 3.2 gm/dL (4.64 umol/L). Which risk factors and treatment strategies should be considered for further evaluation and management?

Acknowledgments

Support: Sagar U. Nigwekar is supported by the National Kidney Foundation's Young Investigator Award, the Fund for Medical Discovery Award from the Massachusetts General Hospital's Executive Committee on Research (R00000000007190), and by the American Heart Association's Mentored Clinical and Population Research Award (15CRP22900008).

Disclosures: Sagar U. Nigwekar reports receiving lecture honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis and is a prior recipient of Nephrology Fellowship Award from Sanofi-Aventis. Ravi I. Thadhani is a consultant to Fresenius Medical Care North America and has received a research grant from Abbott Laboratories.

References

- 1.Selye H, Gentile G, Prioreschi P. Cutaneous molt induced by calciphylaxis in the rat. Science. 1961;134(3493):1876–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3493.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees JK, Coles GA. Calciphylaxis in man. British medical journal. 1969;2(5658):670–672. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5658.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skalnik J, Vasku J, Urbanek E. Calciphylaxis and cerebral atrophy in man. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1970;69:172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson DC, Stewart WK, Piercy DM. Calcifying panniculitis with fat and skin necrosis in a case of uraemia with autonomous hyperparathyroidism. Lancet. 1968;2(7563):323–325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budisavljevic MN, Cheek D, Ploth DW. Calciphylaxis in chronic renal failure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1996;7(7):978–982. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V77978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. Journal of nephrology. 2011;24(2):142–148. doi: 10.5301/jn.2011.6366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012;27(4):1314–1318. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nigwekar SU. An unusual case of nonhealing leg ulcer in a diabetic patient. Southern medical journal. 2007;100(8):851–852. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3180f6100c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, Hix JK. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008;3(4):1139–1143. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00530108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allegretti AS, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, Nigwekar SU. Calciphylaxis: a rare but fatal delayed complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014;64(2):274–277. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney international. 2002;61(6):2210–2217. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007;56(4):569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1995;33(6):954–962. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigwekar SU, Solid CA, Ankers E, et al. Quantifying a rare disease in administrative data: the example of calciphylaxis. Journal of general internal medicine. 2014;29(Suppl 3):724–731. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigwekar SU, Bhan I, Turchin A, et al. Statin use and calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a matched case-control study. American journal of nephrology. 2013;37(4):325–332. doi: 10.1159/000348806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewster UC. Dermatological disease in patients with CKD. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2008;51(2):331–344. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dauden E, Onate MJ. Calciphylaxis. Dermatologic clinics. 2008;26(4):557–568. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edelstein CL, Wickham MK, Kirby PA. Systemic calciphylaxis presenting as a painful, proximal myopathy. Postgraduate medical journal. 1992;68(797):209–211. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.68.797.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo T, Tsukamoto Y, Tamura M, et al. Acute respiratory failure due to “pulmonary calciphylaxis” in a maintenance haemodialysis patient. Nephron. 2001;87(1):75–79. doi: 10.1159/000045887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsamakis G, Lukovits TG, Gorelick PB. Calcific cerebral embolism in systemic calciphylaxis. Neurology. 1998;51(1):295–297. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. Journal of clinical neuromuscular disease. 2014;15(3):108–111. doi: 10.1097/CND.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols B, Saadat P, Vadmal MS. Fatal systemic nonuremic calciphylaxis in a patient with primary autoimmune myelofibrosis. International journal of dermatology. 2011;50(7):870–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuthill MH, Stratton J, Warrens AN. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy presenting with small and large bowel involvement. Journal of nephrology. 2006;19(1):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korzets A, Marashek I, Schwartz A, Rosenblatt I, Herman M, Ori Y. Ischemic optic neuropathy in dialyzed patients: a previously unrecognized manifestation of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004;44(6):e93–97. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moe SM, Chen NX. Calciphylaxis and vascular calcification: a continuum of extra-skeletal osteogenesis. Pediatric nephrology. 2003;18(10):969–975. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, Berghold A, Aberer E. Calcinosis cutis: part I. Diagnostic pathway. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;65(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.038. quiz 13-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Essary LR, Wick MR. Cutaneous calciphylaxis. An underrecognized clinicopathologic entity. American journal of clinical pathology. 2000;113(2):280–287. doi: 10.1309/AGLF-X21H-Y37W-50KL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mochel MC, Arakaki RY, Wang G, Kroshinsky D, Hoang MP. Cutaneous calciphylaxis: a retrospective histopathologic evaluation. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2013;35(5):582–586. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31827c7f5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Au S, Crawford RI. Three-dimensional analysis of a calciphylaxis plaque: clues to pathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002;47(1):53–57. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden MR, Kolb LG, Khanna R. Calciphylaxis and the cardiometabolic syndrome. Journal of the cardiometabolic syndrome. 2006;1(1):76–79. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-3118.2006.05459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, MacDonald AS. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2000;35(4):588–597. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weenig RH. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;58(3):458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sowers KM, Hayden MR. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2010;3(2):109–121. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selye H, Dieudonne JM. Calcification of the parathyroids induced by calciphylaxis. Experientia. 1961;17:496–497. doi: 10.1007/BF02158617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selye H, Gentile G, Jean P. An experimental model of “dermatomyositis” induced by calciphylaxis. Canadian Medical Association journal. 1961;85:770–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selye H, Grasso S, Dieudonne JM. On the role of adjuvants in calciphylaxis. Review of allergy. 1961;15:461–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2014;25(4):1411–1414. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2580-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB, et al. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998;32(3):384–391. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Llach F. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): an evolving entity? American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998;32(3):514–518. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nigwekar SU, Tamez H, Thadhani RI. Vitamin D and chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disease (CKD-MBD) BoneKEy reports. 2014;3:498. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bleyer AJ, Choi M, Igwemezie B, de la Torre E, White WL. A case control study of proximal calciphylaxis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998;32(3):376–383. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janigan DT, Perey B, Marrie TJ, Chiasson PM, Hirsch D. Skin necrosis: an unusual complication of hyperphosphatemia during total parenteral nutrition therapy. JPEN Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 1997;21(1):50–52. doi: 10.1177/014860719702100150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.London GM, Marty C, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, Metivier F, de Vernejoul MC. Arterial calcifications and bone histomorphometry in end-stage renal disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2004;15(7):1943–1951. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000129337.50739.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Araya CE, Fennell RS, Neiberger RE, Dharnidharka VR. Sodium thiosulfate treatment for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in children and young adults. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2006;1(6):1161–1166. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01520506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng J, Gohara M, Lazova R, Antaya RJ. Fatal childhood calciphylaxis in a 10-year-old and literature review. Pediatric dermatology. 2006;23(3):266–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed S, O'Neill KD, Hood AF, Evan AP, Moe SM. Calciphylaxis is associated with hyperphosphatemia and increased osteopontin expression by vascular smooth muscle cells. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2001;37(6):1267–1276. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.24533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nigwekar SU, Brunelli SM, Meade D, Wang W, Hymes J, Lacson E., Jr Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8(7):1162–1170. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09880912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JL, Naguwa SM, Cheema G, Gershwin ME. Recognizing calcific uremic arteriolopathy in autoimmune disease: an emerging mimicker of vasculitis. Autoimmunity reviews. 2008;7(8):638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James LR, Lajoie G, Prajapati D, Gan BS, Bargman JM. Calciphylaxis precipitated by ultraviolet light in a patient with end-stage renal disease secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1999;34(5):932–936. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris RJ, Cropley TG. Possible role of hypercoagulability in calciphylaxis: review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64(2):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sewell LD, Weenig RH, Davis MD, McEvoy MT, Pittelkow MR. Low-dose tissue plasminogen activator for calciphylaxis. Archives of dermatology. 2004;140(9):1045–1048. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.9.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez-Mijares R, Guzman-Zamudio JL, Payan-Lopez J, Rodriguez-Fernandez A, Gomez-Fernandez P, Almaraz-Jimenez M. Calciphylaxis in a haemodialysis patient: functional protein S deficiency? Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 1996;11(9):1856–1859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sankarasubbaiyan S, Scott G, Holley JL. Cryofibrinogenemia: an addition to the differential diagnosis of calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998;32(3):494–498. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Seminars in dialysis. 2002;15(3):172–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2002.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slough S, Servilla KS, Harford AM, Konstantinov KN, Harris A, Tzamaloukas AH. Association between calciphylaxis and inflammation in two patients on chronic dialysis. Advances in peritoneal dialysis Conference on Peritoneal Dialysis. 2006;22:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Angelis M, Wong LL, Myers SA, Wong LM. Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: a prevalence study. Surgery. 1997;122(6):1083–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90212-9. discussion 1089-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sprague SM. Painful skin ulcers in a hemodialysis patient. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9(1):166–173. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mazhar AR, Johnson RJ, Gillen D, et al. Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Kidney international. 2001;60(1):324–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayashi M, Takamatsu I, Kanno Y, et al. A case-control study of calciphylaxis in Japanese end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012;27(4):1580–1584. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zacharias JM, Fontaine B, Fine A. Calcium use increases risk of calciphylaxis: a case-control study. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 1999;19(3):248–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruggian JC, Maesaka JK, Fishbane S. Proximal calciphylaxis in four insulin-requiring diabetic hemodialysis patients. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1996;28(3):409–414. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90499-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farah M, Crawford RI, Levin A, Chan Yan C. Calciphylaxis in the current era: emerging ‘ironic’ features? Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011;26(1):191–195. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Danziger J. Vitamin K-dependent proteins, warfarin, and vascular calcification. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008;3(5):1504–1510. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00770208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nazarian RM, Van Cott EM, Zembowicz A, Duncan LM. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009;61(2):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ng AT, Peng DH. Calciphylaxis. Dermatologic therapy. 2011;24(2):256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2011.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schafer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, et al. The serum protein alpha 2-Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112(3):357–366. doi: 10.1172/JCI17202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shmidt E, Murthy NS, Knudsen JM, et al. Net-like pattern of calcification on plain soft-tissue radiographs in patients with calciphylaxis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;67(6):1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han MM, Pang J, Shinkai K, Franc B, Hawkins R, Aparici CM. Calciphylaxis and bone scintigraphy: case report with histological confirmation and review of the literature. Annals of nuclear medicine. 2007;21(4):235–238. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norris B, Vaysman V, Line BR. Bone scintigraphy of calciphylaxis: a syndrome of vascular calcification and skin necrosis. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2005;30(11):725–727. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000182215.97219.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vedvyas C, Winterfield LS, Vleugels RA. Calciphylaxis: a systematic review of existing and emerging therapies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;67(6):e253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baldwin C, Farah M, Leung M, et al. Multi-intervention management of calciphylaxis: a report of 7 cases. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;58(6):988–991. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar--to debride or not to debride? Ostomy/wound management. 2004;50(4):64–66. 68–70. discussion 71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bechara FG, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Should we perform surgical debridement in calciphylaxis? Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery et al. 2009;35(3):554–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sato T, Ichioka S. How should we manage multiple skin ulcers associated with calciphylaxis? The Journal of dermatology. 2012;39(11):966–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zitt E, Konig M, Vychytil A, et al. Use of sodium thiosulphate in a multi-interventional setting for the treatment of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2013;28(5):1232–1240. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wollina U, Helm C, Hansel G, et al. Deep ulcer shaving combined with split-skin transplantation in distal calciphylaxis. The international journal of lower extremity wounds. 2008;7(2):102–107. doi: 10.1177/1534734608317891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barnett A, Berkowitz RL, Mills R, Vistnes LM. Comparison of synthetic adhesive moisture vapor permeable and fine mesh gauze dressings for split-thickness skin graft donor sites. American journal of surgery. 1983;145(3):379–381. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Basile C, Montanaro A, Masi M, Pati G, De Maio P, Gismondi A. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series. Journal of nephrology. 2002;15(6):676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deng Y, Xie G, Li C, et al. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy ameliorated by hyperbaric oxygen therapy in high-altitude area. Renal failure. 2014;36(7):1139–1141. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2014.917672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Podymow T, Wherrett C, Burns KD. Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2001;16(11):2176–2180. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.11.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tittelbach J, Graefe T, Wollina U. Painful ulcers in calciphylaxis - combined treatment with maggot therapy and oral pentoxyfillin. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2001;12(4):211–214. doi: 10.1080/09546630152696035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Picazo M, Bover J, de la Fuente J, Sans R, Cuxart M, Matas M. Sterile maggots as adjuvant procedure for local treatment in a patient with proximal calciphylaxis. Nefrologia : publicacion oficial de la Sociedad Espanola Nefrologia. 2005;25(5):559–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davison SN. The prevalence and management of chronic pain in end-stage renal disease. Journal of palliative medicine. 2007;10(6):1277–1287. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polizzotto MN, Bryan T, Ashby MA, Martin P. Symptomatic management of calciphylaxis: a case series and review of the literature. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2006;32(2):186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nayak-Rao S. Achieving effective pain relief in patients with chronic kidney disease: a review of analgesics in renal failure. Journal of nephrology. 2011;24(1):35–40. doi: 10.5301/jn.2010.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dean M. Opioids in renal failure and dialysis patients. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2004;28(5):497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chan MR, Ghandour F, Murali NS, Washburn M, Astor BC. Pilot Study of the Effect of Lanthanum Carbonate (Fosrenol(R)) In Patients with Calciphylaxis: A Wisconsin Network for Health Research (WiNHR) Study. Journal of nephrology & therapeutics. 2014;4(3):1000162. doi: 10.4172/2161-0959.1000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fine A, Fontaine B. Calciphylaxis: the beginning of the end? Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 2008;28(3):268–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moorthi RN, Moe SM. CKD-mineral and bone disorder: core curriculum 2011. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;58(6):1022–1036. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Russell R, Brookshire MA, Zekonis M, Moe SM. Distal calcific uremic arteriolopathy in a hemodialysis patient responds to lowering of Ca × P product and aggressive wound care. Clinical nephrology. 2002;58(3):238–243. doi: 10.5414/cnp58238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pallure V, Comte C, Leray-Mouragues H, Dereure O. Cinacalcet as first-line treatment for calciphylaxis. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2008;88(1):62–63. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mohammed IA, Sekar V, Bubtana AJ, Mitra S, Hutchison AJ. Proximal calciphylaxis treated with calcimimetic ‘Cinacalcet’. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2008;23(1):387–389. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Velasco N, MacGregor MS, Innes A, MacKay IG. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with cinacalcet-an alternative to parathyroidectomy? Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2006;21(7):1999–2004. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Perkovic V, Neal B. Trials in kidney disease--time to EVOLVE. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(26):2541–2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1212368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Headley CM. Hungry bone syndrome following parathyroidectomy. ANNA journal/American Nephrology Nurses' Association. 1998;25(3):283–289. quiz 290-281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lal G, Nowell AG, Liao J, Sugg SL, Weigel RJ, Howe JR. Determinants of survival in patients with calciphylaxis: a multivariate analysis. Surgery. 2009;146(6):1028–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kriskovich MD, Holman JM, Haller JR. Calciphylaxis: is there a role for parathyroidectomy? The Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):603–607. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kang AS, McCarthy JT, Rowland C, Farley DR, van Heerden JA. Is calciphylaxis best treated surgically or medically? Surgery. 2000;128(6):967–971. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.110429. discussion 971-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ackermann F, Levy A, Daugas E, et al. Sodium thiosulfate as first-line treatment for calciphylaxis. Archives of dermatology. 2007;143(10):1336–1337. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.10.1336. author reply 1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hemodialysis Adequacy Work G. Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S2–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.New N, Mohandas J, John GT, et al. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy in peritoneal dialysis populations. International journal of nephrology. 2011;2011:982854. doi: 10.4061/2011/982854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Don BR, Chin AI. A strategy for the treatment of calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) employing a combination of therapies. Clinical nephrology. 2003;59(6):463–470. doi: 10.5414/cnp59463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hayden MR, Goldsmith DJ. Sodium thiosulfate: new hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Seminars in dialysis. 2010;23(3):258–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Noureddine L, Landis M, Patel N, Moe SM. Efficacy of sodium thiosulfate for the treatment for calciphylaxis. Clinical nephrology. 2011;75(6):485–490. doi: 10.5414/cnp75485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sood AR, Wazny LD, Raymond CB, et al. Sodium thiosulfate-based treatment in calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a consecutive case series. Clinical nephrology. 2011;75(1):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004;43(6):1104–1108. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Selk N, Rodby RA. Unexpectedly severe metabolic acidosis associated with sodium thiosulfate therapy in a patient with calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Seminars in dialysis. 2011;24(1):85–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mao M, Lee S, Kashani K, Albright R, Qian Q. Severe anion gap acidosis associated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate administration. Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 2013;9(3):274–277. doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schlieper G, Brandenburg V, Ketteler M, Floege J. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2009;5(9):539–543. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O'Neill WC. Sodium thiosulfate: mythical treatment for a mysterious disease? Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8(7):1068–1069. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04990513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.O'Neill WC, Hardcastle KI. The chemistry of thiosulfate and vascular calcification. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012;27(2):521–526. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pasch A, Schaffner T, Huynh-Do U, Frey BM, Frey FJ, Farese S. Sodium thiosulfate prevents vascular calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney international. 2008;74(11):1444–1453. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen NX, O'Neill K, Akl NK, Moe SM. Adipocyte induced arterial calcification is prevented with sodium thiosulfate. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2014;449(1):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Singh RP, Derendorf H, Ross EA. Simulation-based sodium thiosulfate dosing strategies for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2011;6(5):1155–1159. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09671010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gupta DR, Sangha H, Khanna R. Chemical peritonitis after intraperitoneal sodium thiosulfate. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 2012;32(2):220–222. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sherman C. Chemical peritonitis after intraperitoneal sodium thiosulfate. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 2013;33(1):104. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Strazzula L, Nigwekar SU, Steele D, et al. Intralesional sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis. JAMA dermatology. 2013;149(8):946–949. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.el-Azhary RA, Arthur AK, Davis MD, et al. Retrospective analysis of tissue plasminogen activator as an adjuvant treatment for calciphylaxis. JAMA dermatology. 2013;149(1):63–67. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Iwagami M, Mochida Y, Ishioka K, et al. LDL-apheresis dramatically improves generalized calciphylaxis in a patient undergoing hemodialysis. Clinical nephrology. 2014;81(3):198–202. doi: 10.5414/CN107482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Levy R. Potential treatment of calciphylaxis with vitamin K(2): Comment on the article by Jacobs-Kosmin and DeHoratius. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2007;57(8):1575–1576. doi: 10.1002/art.23107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Musso CG, Enz PA, Guelman R, et al. Non-ulcerating calcific uremic arteriolopathy skin lesion treated successfully with intravenous ibandronate. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 2006;26(6):717–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2006;48(1):151–154. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Torregrosa JV, Duran CE, Barros X, et al. Successful treatment of calcific uraemic arteriolopathy with bisphosphonates. Nefrologia : publicacion oficial de la Sociedad Espanola Nefrologia. 2012;32(3):329–334. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2012.Jan.11137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Torregrosa JV, Sanchez-Escuredo A, Barros X, Blasco M, Campistol JM. Clinical management of calcific uremic arteriolopathy before and after therapeutic inclusion of bisphosphonates. Clinical nephrology. 2013 doi: 10.5414/CN107923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bhat S, Hegde S, Bellovich K, El-Ghoroury M. Complete resolution of calciphylaxis after kidney transplantation. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013;62(1):132–134. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sibai H, Ishak RS, Halawi R, et al. Non-uremic calcific arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma: a previously unreported association. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(7):e88–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dominguez AR, Goldman SE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis treated with teriparatide. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014;70(2):e41–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Erdel BL, Juneja R, Evans-Molina C. A case of calciphylaxis in a patient with hypoparathyroidism and normal renal function. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2014;20(6):e102–105. doi: 10.4158/EP13509.CR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ning MS, Dahir KM, Castellanos EH, McGirt LY. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of non-uremic calciphylaxis. The Journal of dermatology. 2013;40(8):649–652. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Almafragi A, Vandorpe J, Dujardin K. Calciphylaxis in a cardiac patient without renal disease. Acta cardiologica. 2009;64(1):91–93. doi: 10.2143/AC.64.1.2034368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rogers NM, Teubner DJ, Coates PT. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: advances in pathogenesis and treatment. Seminars in dialysis. 2007;20(2):150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy Work G. Clinical practice guidelines for peritoneal dialysis adequacy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S98–129. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Number of publications in PubMed on calciphylaxis or calcific uremic arteriolopathy between 1961 and 2013