Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between sacroiliac joint (SIJ) contrast dispersal patterns during SIJ corticosteroid injection and pain relief at 2 and 8 weeks after the procedure. The association between the number of positive provocative SIJ physical examination maneuvers (minimum of one in all patients undergoing SIJ injection) and the patient’s response to the intervention was also assessed.

Design

Retrospective chart review.

Setting

Academic outpatient musculoskeletal practice.

Patients

Fifty-four subjects who underwent therapeutic SIJ corticosteroid injection were screened for inclusion; 49 subjects were included in the final analysis.

Methods

A retrospective review of electronic medical records identified patients who underwent SIJ corticosteroid injection. Fluoroscopic contrast flow patterns were categorized as type I (intra-articular injection with cephalad extension within the SIJ) or type II (intra-articular injection with poor cephalad extension). Self-reported numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) values at the time of injection and 2 and 8 weeks after the procedure were recorded. The number of positive provocative SIJ physical examination maneuvers at the time of the initial evaluation was also recorded.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the effect of contrast patterns (type I or type II) on change in NPRS values at 2 weeks and 8 weeks after the injection. The secondary outcome measure was the association between the number of positive provocative SIJ physical examination maneuvers and decrease in the level of pain after the procedure.

Results

At 2 weeks after the procedure, type I subjects demonstrated a significantly lower mean NPRS value compared with type II subjects (2.8 ± 1.4 versus 3.8 ± 1.6, respectively, P =.02). No statistically significant difference was observed at 8 weeks after the procedure. NPRS values were significantly reduced both at 2 weeks and 8 weeks, compared with baseline, in both subjects identified as having type I flow and those with type II flow (P < .0001 for all within-group comparisons).

Conclusions

Fluoroscopically guided corticosteroid injections into the SIJ joint are effective in decreasing NPRS values in patients with SIJ-mediated pain. Delivery of corticosteroid to the superior portion of the SIJ leads to a greater reduction in pain at 2 weeks, but not at 8 weeks. Patients with at least one positive provocative maneuver should benefit from an intra-articular corticosteroid injection.

Introduction

In 1905 Goldthwaite and Osgood first reported that the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) can be a source of low back and leg pain [1]. Today, SIJ pain affects 15%–30% of patients with chronic nonradicular low back pain [2]. This condition can be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge because of overlap in symptomatology with the hip joint and other causes of low back pain.

Clinically, patients with SIJ pain present with discomfort and tenderness at the sacral sulci. Often pain is referred to the posterolateral thigh, buttocks, low lumbar region, and/or groin [3–8], and in some cases it may mimic sciatica [9]. History is often notable for trauma such as a motor vehicle collision, fall onto the buttocks, or repetitive motion injury resulting from running, lifting, or altered gait [10,11]. Painful palpation of the ipsilateral sacral sulcus or provocative SIJ maneuvers such as FABER (flexion, abduction, and external rotation; Patrick’s test), Gaenslen’s test, thigh thrust, gapping, and sacral thrust are routinely performed during physical examination to help localize the source of pain. It has been shown that 3 or more positive provocative tests have a sensitivity of 82%–94% and a specificity of 57%–79% for SIJ pain [2,12–15]. Even when a thorough history and physical examination are performed, some investigators have proposed that a diagnostic injection of local anesthetic may be the only way to accurately diagnose pain originating from the sacroiliac joint [16].

Initial treatment of SIJ pain consists of ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy. Patients who fail to improve with these conservative measures often undergo SIJ intra-articular (IA) corticosteroid injections for diagnosis and pain relief [17]. Evidence for the therapeutic effectiveness of SIJ corticosteroid injections is mixed: individual studies have shown some benefit [18,19], whereas systematic reviews have found limited [20,21] to moderate [22] evidence to support their use.

A lack of strong evidence for the efficacy of SIJ corticosteroid injections may be due to inaccurate placement of the medication. Recently, patterns of contrast dispersal demonstrated on fluoroscopy have been shown to predict immediate, short-term (2 weeks), and intermediate-term (2 months) pain reduction in patients receiving transforaminal epidural steroid injections [23]. To our knowledge, no similar investigations have been published regarding the SIJ.

The purpose of this study is to (1) determine the relationship between contrast dispersal pattern during SIJ arthrography and pain relief at 2 and 8 weeks after the procedure and (2) determine if an association exists between the number of positive provocative SIJ maneuvers and the patient’s response to the corticosteroid injection.

Materials and Methods

Patients

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a retrospective chart review was performed. Patients who underwent SIJ injections between September 2012 and October 2013 were identified, and data were extracted from the electronic medical record.

These patients initially presented with pain in the buttock or posterior thigh that was believed to be somatically derived from the SIJ. Patients were scheduled for SIJ injection if they had pain over the posterior superior iliac spine and one or more positive provocative SIJ maneuvers. Based on investigators’ preference and clinical practice, all patients had results for FABER (Patrick’s test) [24], sacral thrust [25], and Gaenslen’s test [25] recorded in the chart. Patients without any positive provocative tests were not scheduled for a procedure and thus not included in the study, given that when all provocation SIJ tests are negative, symptomatic SIJ disease is less likely and therefore may be ruled out [12]. Patients also were excluded from the study if they had findings suggestive of another source of axial back pain, as well as radiation of symptoms past the knee, less than 5/5 strength in the lower extremity, diminished reflexes, signs of myelopathy, and positive neural tension signs including straight leg raise and/or slump test. Patients undergoing any additional injection for painful symptoms within 3 months of the initial injection and those with a self-reported history of peripheral neuropathy or other neuromuscular disorders were also excluded. Patients younger than 18 years, prisoners, and those with worker’s compensation or legal claims pending because of injury were also excluded from the final analysis.

Chart Review

A retrospective chart review was performed to identify all patients undergoing SIJ injection between September 2012 and October 2013 who met the aforementioned criteria. Baseline demographic data collected included age, gender, duration of symptoms, history of prior SIJ injection, and history of lumbar spinal fusion. In addition, response (either positive or negative) to 3 SIJ provocative maneuvers (sacral thrust, FABER, and Gaenslen’s test) and preinjection numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) scores ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain) were obtained. NPRS values at 2 and 8 weeks after the injection were also recorded.

Injection

All SIJ corticosteroid injections were performed by a single physician trained via fellowship in pain medicine (JRS) using a posterior approach with a standard single-beam C-arm fluoroscope. Anterior-posterior, contralateral oblique, and lateral views were used to guide needle placement. Once the needle tip was believed to be in the IA position, 0.5 mL of iohexol (Omnipaque 180, GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) was injected. Anterior-posterior images with live fluoroscopy were saved to the picture archiving and communication system. A uniform dose of 1 mL of 2% preservative-free lidocaine hydrochloride (AAP Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL) combined with 1 mL of triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL (Bristol-Meyers Squibb Co, New Brunswick, NJ) was injected. The needle was removed, a sterile dressing was applied, and the patient was transferred to the recovery area for 15 minutes of monitoring.

Arthrogram Classification

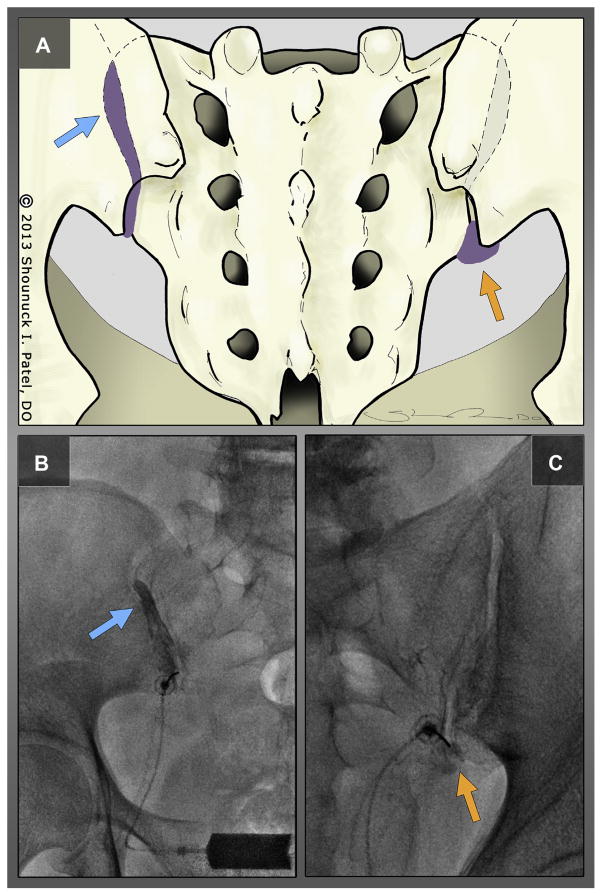

De-identified fluoroscopic images of contrast injection for each subject were analyzed in random order independently by 2 authors (PMS and JRS) and categorized by contrast dispersal pattern into 1 of 2 types (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

(A) Posterior view of a sacroiliac joint showing type I (blue arrow) and type II (orange arrow) contrast flow patterns with characteristic fluoroscopic images of type I flow, (B) depicting excellent cephalad extension of contrast within the sacroiliac joint (blue arrow) and type II flow, and (C) with poor cephalad flow and collection of contrast material in the inferior recess (arrow).

Type I—IA flow with cephalad extension of contrast dispersion outlining the superior aspect of the sacroiliac joint.

Type II—IA flow with poor cephalad extension of contrast within the sacroiliac joint that fails to reach the most superior portion.

The images were also inspected for any evidence of extra-articular flow. Any discrepancies in categorization were resolved through consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (including mean, standard deviation, median, range, frequency, and percent) were calculated to characterize the type I and II cohorts. The 2-sample t-test, χ2 test, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare age, gender, and symptom duration, respectively, between the type I and II cohorts.

Primary Outcome: Injection Patterns

The paired t-test was used to compare the mean NPRS value between (1) preinjection (baseline) and 2 weeks after the procedure and between (2) preinjection (baseline) and 8 weeks after the procedure in the type I and II cohorts, separately. The 2-sample t-test was used to compare the mean NPRS value between the type I and II cohorts at baseline, 2 weeks after the procedure, and 8 weeks after the procedure. The 2-sample t-test was also used to compare mean change (with change defined as baseline to 2 weeks and baseline to 8 weeks) between the type I and II cohorts. Analysis of covariance was also used to compare the mean NPRS value between the 2 cohorts at 2 and 8 weeks, controlling for baseline NPRS value (eg, to confirm the 2-sample t-test results). Based on recent work to define data-driven standardized clinically relevant changes in pain scale scores, a successful outcome was defined by a decrease in the numerical rating scale by at least 1.8 points [26,27] and was determined for each of the 2 groups. The percentage of subjects in each group achieving successful outcome (at 2 weeks and 8 weeks) was compared using the χ2 test.

Secondary Outcome: Provocative Maneuvers

The paired t-test was used to compare the mean NPRS value between (1) preinjection (baseline) and 2 weeks after the procedure and between (2) preinjection (baseline) and 8 weeks after the procedure in subjects with 1, 2, or 3 positive provocative SIJ maneuvers, separately (both types were combined for this analysis).

All P values are 2-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the .05 α level. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons because of the exploratory (ie, hypothesis-generating) nature of the study and the small sample size available in each of the cohorts. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to assess the precision of the obtained estimates. All analyses were performed in SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

We identified 54 subjects who underwent SIJ injection during the specified period. Five of these patients were excluded from the final analysis: 1 who had undergone a prior SIJ injection within 3 months, 1 because of contrast allergy (contrast was not used at the time of the procedure), 2 because of poor-quality images that could not be accurately classified as type I or type II, and 1 for which there was no image available in the electronic record for review. None of the images showed evidence of extravasation of contrast material outside the joint, either through rents in the mid portion of the joint capsule or through a disrupted inferior capsular recess. A total of 49 injections, all of which were unilateral, ultimately underwent classification as type I or II and were included in the final analysis (Table 1). The investigators agreed on flow pattern for 45 of the 49 independently reviewed procedures and reached a consensus on the remaining 4 procedures after reviewing the imaging together.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data

| Type I (N = 27) | Type II (N = 22) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 56.4 ± 15.3 | 51.0 ± 19.4 | .28 |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 5 (18.5) | 7 (31.8) | .28 |

| Female | 22 (81.5) | 15 (68.2) | |

| Duration of symptoms, wk, median (range) | 10 (4–17) | 8 (4–16) | .10 |

| Pain at baseline, mean ± SD | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 1.9 | .67 |

SD = standard deviation.

Fifty-five percent (27/49) had type I flow and 45% had type II flow. Subjects with type I flow had a mean age of 56.4 ± 15.3 years (range: 26–82) versus 41.0 ± 19.4 years (range: 20–89) for subjects with type II flow (P = .28). Type I and II subjects were similar with respect to female gender (81.5% versus 68.2%, respectively, P = .28), and were similar with respect to duration of painful symptoms (median = 10 weeks [range: 4–17] versus median = 8 weeks [range: 4–16], respectively; P = .10). Baseline NPRS values in subjects with type I and type II flow patterns were similar (6.6 ± 1.9 versus 6.3 ± 1.9, respectively; P = .67; Table 1). In addition, one patient with type II flow had a history of L4–L5 spinal fusion. Three patients (2 type I and 1 type II) had repeat injections performed >8 weeks after the initial procedure because of persistent painful symptoms.

At 2 weeks after the procedure, type I subjects demonstrated a statistically significant lower mean NPRS value compared with type II subjects (2.8 ± 1.4 versus 3.8 ± 1.6, respectively; P = .02). At 8 weeks after the procedure, type I and II subjects demonstrated similar mean NPRS values (4.0 ± 1.6 versus 4.3 ± 2.0, respectively; P = .64; Table 2). Change from baseline to 2 weeks was significantly greater among type I subjects compared with type II subjects (mean change = −3.7 ± 2.4 versus −2.5 ± 1.2, respectively; P = .02), whereas change from baseline to 8 weeks was not different between type I and II subjects (mean change = −2.5 ± 1.9 versus −2.0 ± 1.6, respectively; P = .36). Analysis of covariance analyses (at 2 weeks and 8 weeks) comparing mean NPRS between type I and II subjects, adjusted for baseline NPRS, revealed similar findings (P = .01 at 2 weeks and P = .43 at 8 weeks, with type I subjects only demonstrating lower adjusted mean NPRS values than type II subjects at 2 weeks). Nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests confirmed the same findings (data not shown).

Table 2.

Mean numeric pain rating scale comparison between type I and type II groups at 2 weeks and 8 weeks after the injection

| Type I | Type II | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | −1.00 (−1.87, −0.14) | .02 |

| 8 weeks | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | −0.24 (−1.25, 0.78) | .64 |

CI = confidence interval.

From 2-sample t-test.

Successful outcome (ie, an NPRS decrease of 1.8 points or greater) after 2 weeks was found in 85.2% of the subjects in the type I group versus 81.8% of the subjects in the type II group (P = .75). Similarly, no difference in successful outcome between type I and type II subjects was observed at 8 weeks (66.7% versus 63.6%, respectively, P = .83; Table 3).

Table 3.

Successful outcome (determined by decrease of ≥1.8 on the numeric pain rating scale)

| Type I (N = 27) N (%) |

Type II (N = 22) N (%) |

P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 23 (85.2) | 18 (81.8) | .75 |

| 8 weeks | 18 (66.7) | 14 (63.6) | .83 |

From χ2 test.

NPRS values were reduced at 2 weeks, compared with baseline, in both subjects identified as having type I flow (2.8 ± 1.4 versus 6.6 ± 1.9, respectively; P <.0001) and subjects with type II flow (3.8 ± 1.6 versus 6.3 ± 1.9, respectively; P < .0001). Similarly, NPRS values were reduced at 8 weeks compared with baseline in both subjects identified as having type I flow (4.0 ± 1.6 versus 6.6 ± 1.9, respectively; P <.0001) and those with type II flow (4.3 ± 2.0 versus 6.3 ± 1.9, respectively; P < .0001; Table 4).

Table 4.

Change in numeric pain rating scale from baseline in type I and type II groups

| Baseline | 2 Weeks | P Value* (Baseline vs 2 Weeks) | 8 Weeks | P Value (Baseline vs 8 Weeks) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | <.0001 | 4.0 ± 1.6 | <.0001 |

| Type II | 6.3 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | <.0001 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | <.0001 |

From paired t-test.

All 49 subjects had documented results of sacral thrust, FABER, and Gaenslen’s maneuvers. Thirty-seven percent (18/49) had 1 positive provocative maneuver, 37% (18/49) had 2 positive maneuvers, and 26% (13/49) had 3 positive maneuvers (Table 5). Mean NPRS values were reduced from baseline in all 3 maneuver groups both at 2 weeks and 8 weeks after the injection (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pain relief from sacroiliac joint based on number of provocative maneuvers

| No. of positive tests | N | Pain at Baseline | Pain at 2 Weeks | P Value (Baseline vs 2 Weeks) | Pain at 8 Weeks | P Value (Baseline vs 8 Weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 3.4 ± 1.4 | <.0001 | 4.8 ± 1.5 | .001 |

| 2 | 18 | 6.8 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.5 | <.0001 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | <.0001 |

| 3 | 13 | 6.5 ± 2.6 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | <.0001 | 3.6 ± 2.0 | <.0001 |

Discussion

The SIJ is a source of mechanical, nonradicular low back pain in 15%–30% of cases [2], and when it is severe, it contributes to significant functional impairments. Targeted delivery of anti-inflammatory medication using image-guided injections into the SIJ has emerged as a common treatment modality; however, the data for the efficacy of these injections has been mixed between individual studies [18,19] and systematic reviews [20–22].

The lack of strong evidence for IA SIJ corticosteroid injections may be due in part to (1) imprecise placement of the therapeutic agent or (2) difficulty in establishing the correct diagnosis. Accurate placement of medication within the SIJ is successful without fluoroscopy in only 12% of patients [28]; however, when fluoroscopy is utilized, the procedure has been reported to be 97% successful [29]. Given this outcome, image guidance is often used [30].

Some practitioners use fluoroscopic guidance to confirm proper positining of the needle tip within the SIJ but do not routinely use contrast enhancement to confirm IA placement of the injectate. While placement of the needle tip deep to the posterior SIJ capsule can be confirmed with imaging (fluoroscopy or ultrasound), true IA delivery of medication can only be confirmed with the use of contrast material. The extent of flow of contrast material defines the potential distribution of the therapeutic agent. If contrast material does not flow to all portions of the joint, one must consider the reasons for flow restriction. The restriction may be due to the direction of the needle, trauma-induced changes to the joint surface, a mass, or a narrowed joint space. If flow is restricted for a reason other than direction or placement of the needle, the same mechanism may prevent the anti-inflammatory agent from reaching all affected portions of the joint, which could have therapeutic implications.

Recently Paidin et al [23] have shown that contrast dispersal patterns can predict clinical outcomes in patients receiving epidural corticosteroid injections in the lumbar spine for painful radicular symptoms. We have adapted this concept to the SIJ and have shown in this retrospective review that 2-week outcomes differ based on contrast pattern in fluoroscopically guided SIJ corticosteroid injections, whereas 8-week outcomes do not differ. Patients with cephalad extension of contrast material (type I flow) have greater reductions in pain at 2 weeks but not at 8 weeks compared with patients in whom there is no cephalad flow (type II flow). Furthermore, successful outcomes at both 2 weeks and 8 weeks after the injection occur similarly among type I and II patients. These results imply that spending additional time repositioning the needle during the procedure to obtain more cephalad flow does not necessarily improve pain reduction at 8 weeks after the procedure. Injection of the therapeutic agent once IA spread of contrast material is observed, regardless of how far cephalad it extends, is sufficient to achieve similar results up to 8 weeks after the procedure. The reason patients with type I flow achieve greater pain relief at 2 weeks but not at 8 weeks cannot be determined from the data collected in this study. However, this result may be interpreted to suggest that the observed short-term (2-week) therapeutic benefit of SIJ corticosteroid injections is dependent on complete coverage of affected joint surfaces, whereas longer-term (8-week) effects depend on other unknown factors. Further studies are required to test this hypothesis and better understand the mechanism underlying this finding.

All subjects in the present study had at least one positive provocative SIJ maneuver. The results suggest that when SIJ pain is appropriately diagnosed with SIJ maneuvers, patients do receive short-term reduction in pain from therapeutic SIJ injection. Previous studies have shown sensitivities greater than 80% and specificity near 60% for SIJ pain with 3 positive provocative tests [2,12–15]; however, these results focused on diagnostic accuracy rather than short-term response to injection.

Limitations

This small retrospective study analyzed pain scores in patients who underwent SIJ corticosteroid injection. The study did not include a control group to compare conservative to interventional treatment in these patients. Although the investigators who classified flow patterns were blinded to the patient being evaluated, one of these investigators was also the physician who performed the injections and may have associated certain details of the case with patient outcomes, thus potentially introducing bias. Furthermore, although the data from this study suggested that patients with one or more positive provocative maneuvers received benefit from an injection, analysis was not performed to compare short-term efficacy between groups. Yet another limitation is the lack of a comparison group in which the SIJ corticosteroid injections were performed without injection of contrast material. However, the data from such a group would likely be heterogeneous, given a mixture of contrast dispersal patterns. In this theoretical “noncontrast” group, drawing any meaningful conclusions would prove to be difficult.

Conclusions

Fluoroscopically guided corticosteroid injections into the SIJ joint are effective in decreasing NPRS values up to 8 weeks after the procedure in patients with SIJ-mediated pain. Based on the results of this study, delivery of a corticosteroid to the superior aspect of the SIJ (type I flow) leads to a greater reduction in pain at 2 weeks when compared with type II injections. Patients with at least one positive provocative maneuver should benefit from an IA corticosteroid injection.

Contributor Information

Paul M. Scholten, Weill Cornell Medical Center, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Baker Pavilion, 16th Floor, 525 E 68th St, New York, NY 10065. Disclosure: nothing to disclose.

Shounuck I. Patel, Rutgers University–New Jersey Medical School/Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation, Newark, NJ. Disclosure: nothing to disclose.

Paul J. Christos, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY. Disclosures related to this publication: grant, Clinical Translational Science Center #UL1-TR000457-06 (money to institution); fees for participation in review activities, Weill Cornell Biostatistics Core (money to institution).

Jaspal R. Singh, Weill Cornell Medical Center, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Baker Pavilion, 16th Floor, 525 E 68th St, New York, NY 10065. Disclosure: nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Goldthwait JE, Osgood RB. A consideration of the pelvic articulations from an anatomical, pathological and clinical standpoint. Boston Med Surg J. 1905;152:593–601. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen SP, Chen Y, Neufeld NJ. Sacroiliac joint pain: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. [Accessed October 28, 2014];Expert Rev Neurother. 2013 13:99–116. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.148. Available at: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=23253394&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: Pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique: Part I: Asymptomatic volunteers. Spine. 1994;19:1475–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortin JD, Aprill CN, Ponthieux B, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: Pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique: Part II: Clinical evaluation. Spine. 1994;19:1483–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung JH, Kim HI, Shin DA, et al. Usefulness of pain distribution pattern assessment in decision-making for the patients with lumbar zygapophyseal and sacroiliac joint arthropathy. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:1048–1054. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.6.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laplante BL, Ketchum JM, Saullo TR, DePalma MJ. Multivariable analysis of the relationship between pain referral patterns and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slipman CW, Jackson HB, Lipetz JS, Chan KT, Lenrow D, Vresilovic EJ. Sacroiliac joint pain referral zones. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:334–338. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Wurff P, Buijs EJ, Groen GJ. Intensity mapping of pain referral areas in sacroiliac joint pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buijs E, Visser L, Groen G. Sciatica and the sacroiliac joint: A forgotten concept. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:713–716. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aydin SM, Gharibo CG, Mehnert M, Stitik TP. The role of radiofrequency ablation for sacroiliac joint pain: A meta-analysis. PM R. 2010;2:842–851. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou LH, Slipman CW, Bhagia SM, et al. Inciting events initiating injection-proven sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Med. 2004;5:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: Validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Manual Therapy. 2005;10:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuber KJ. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2007;51:30–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Systematic review of tests to identify the disc, SIJ or facet joint as the source of low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1539–1550. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0391-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez RSGM. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: A systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10:354–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen M, Pauza K, McLarty J, Bogduk N. The value of medical history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 1996;21:2594–2602. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zochling J. ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:442–452. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luukkainen RK, Wennerstrand PV, Kautiainen HH, Sanila MT, Asikainen EL. Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondylarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maugars Y, Mathis C, Berthelot JM, Charlier C, Prost A. Assessment of the efficacy of sacroiliac corticosteroid injections in spondylarthropathies: A double-blind study. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:767–770. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.8.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen H, Manchikanti L, Simopoulos TT, et al. A systematic evaluation of the therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E247–E278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. Chapter 4 European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:s192–s300. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie-Brown AM, Shah RV, Sehgal N, Everett CR. A systematic review of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2005;8:115–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paidin M, Hansen P, McFadden M, Kendall R. Contrast dispersal patterns as a predictor of clinical outcome with transforaminal epidural steroid injection for lumbar radiculopathy. PM R. 2011;3:1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson HS, Brox JI, Robinson R, Bjelland E, Solem S, Telje T. The reliability of selected motion- and pain provocation tests for the sacroiliac joint. Manual Therapy. 2007;12:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laslett M, Williams M. The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology. Spine. 1994;19:1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199405310-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostelo RWJG, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: Towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine. 2008;33:90–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen HC. Is fluoroscopy necessary for sacroiliac joint injections? Pain Physician. 2003;6:155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dussault RG, Kaplan PA, Anderson MW. Fluoroscopy-guided sacroiliac joint injections. Radiology. 2000;214:273–277. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja28273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg JM, Quint TJ, de Rosayro AM. Computerized tomographic localization of clinically-guided sacroiliac joint injections. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:18–21. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]