Abstract

Objective

The primary objective was to analyze the initial tacrolimus concentrations achieved in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients using the institutional dosing strategy of 1 mg IV daily initiated on day +5. The secondary objectives were to ascertain the tacrolimus dose, days of therapy, and dose changes necessary to achieve a therapeutic concentration, and to identify patient-specific factors that influence therapeutic dose. The relationships between the number of pre-therapeutic days and incidence of graft-versus-host disease and graft failure were delineated.

Methods

A retrospective chart review included adult allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell patients who received tacrolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in 2012. Descriptive statistics, linear and logistic regression, and graphical analyses were utilized.

Results

Ninety-nine patients met the inclusion criteria. The first concentration was subtherapeutic (<10 ng/ml) in 97 patients (98%). The median number of days of tacrolimus needed to achieve a therapeutic trough was 10 with a median of two dose changes. The median therapeutic dose was 1.6 mg IV daily. Approximately 75% of patients became therapeutic on ≤2 mg IV tacrolimus daily. No relationship was found between therapeutic dose and any patient-specific factor tested, including weight. No relationship was found between the number of days of therapy required to achieve a therapeutic trough and incidence of graft-versus-host disease or graft failure.

Conclusion

An initial flat tacrolimus dose of 1 mg IV daily is a suboptimal approach to achieve therapeutic levels at this institution. A dose of 1.6 mg or 2 mg IV daily is a reasonable alternative to the current institutional practice.

Keywords: Tacrolimus, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, immunosuppression, graft-versus-host disease, graft failure

Introduction

Allogeneic blood or bone marrow hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (alloHSCT) is a potentially curative therapeutic option for patients diagnosed with hematologic diseases, such as leukemia, lymphoma and myelodysplastic syndrome. Following either a myeloablative or nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, patients may receive stem cells from an HLA-matched sibling, HLA-matched unrelated donor, umbilical cord blood, or a partially HLA-mismatched (haploidentical) related donor.1 Regardless of the conditioning regimen used or the source of the donated stem cells, post-transplant immunosuppression is necessary to limit the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and graft rejection, which are caused by excessive alloreactivity by donor2 and host3 T cells, respectively. Immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, sirolimus, cyclosporine, methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil are effective at decreasing the incidence and severity of these complications; however, these drugs also put the patient at risk for developing serious infections, toxicities and secondary malignancies.4 GVHD is a leading cause of transplant-related morbidity and mortality. The incidence of acute GVHD (aGVHD) reaches 40–60% in patients transplanted from HLA-identical sibling donors and 75% in patients receiving stem cells from HLA-matched unrelated donors.5 Chronic GVHD (cGVHD) occurs in 40–70% of patients and is responsible for 20–25% of late deaths following alloHSCT.6,7 The incidence of graft failure is up to 25% in recipients of nonmyeloablative alloHSCT compared to 3% in recipients of myeloablative transplants.8

Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that has inhibitory effects on T cell activation and has shown efficacy in preventing and treating aGVHD as well as reversing or stabilizing cGVHD.9 It is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 and 3A5 in the liver and gut and eliminated through biliary excretion. In the blood, it is highly bound to erythrocytes, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein and albumin.4 The pharmacokinetic profile of tacrolimus is similar at steady state when comparing oral, continuous infusion, or 4 h intermittent infusion regimens.10 Blood concentrations are increased by concomitant administration with CYP3A4 enzyme inhibitors such as azole antifungals, erythromycin and amiodarone. CYP3A4 enzyme inducers such as phenobarbital, phenytoin and carbamazepine decrease tacrolimus levels in the blood.11 Appendix 1 lists medications known to interact with tacrolimus. Increased monitoring is necessary and tacrolimus dose adjustment should be made as needed. Tacrolimus has a narrow therapeutic window and an appreciable degree of pharmacokinetic variability.4 Studies in solid organ transplant patients have identified numerous factors which alter the kinetics, including patient age and race, hematocrit and albumin levels, diurnal rhythm, food administration, steroid dosage, diarrhea and metabolizing enzyme expression.12 HSCT-related morbidities such as declining renal function, sinusoidal obstructive syndrome and GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract or liver may also impact pharmacokinetics.4 Calcineurin inhibitors are nephrotoxic and can also cause tremors, headaches, diarrhea, hypertension, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and nausea.13

Many centers begin alloHSCT patients on tacrolimus at 0.03 mg/kg/day by continuous intravenous (IV) infusion beginning 24 h prior to transplant. The package insert indicates that the dose should be based on lean body weight; however, there is controversy over whether actual, ideal, or adjusted body weight may be more appropriate.4,9,13 A 1999 consensus conference concluded that the appropriate dose of tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis was 0.03 mg/kg/day based on lean body weight, often in combination with methotrexate. The use of lean body weight was a departure from actual body weight, which is commonly used to dose cyclosporine. Conference participants agreed on a target range for whole blood concentrations of 10–20 ng/mL, with the first blood level measured between 24 and 48 h after initiation of the infusion.13

At our center, the standard GVHD prophylaxis strategy for myeloablative haploidentical alloHSCT recipients and all nonmyeloablative transplants, irrespective of HLA match status, is post-transplant cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg IBW on days +3 and +4, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 15 mg/kg/dose ABW (rounded to the nearest tablet size if oral, max of 3 gm/day) three times daily on days +5 through +35, and tacrolimus 1 mg IV daily on days +5 through +180. Tacrolimus is administered as a 4 h intermittent infusion (rather than continuous infusion to facilitate outpatient transplants) and is adjusted to achieve a target serum concentration of 10–15 ng/ml.14 Tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil are initiated at least 24 h after the completion of post-transplant cyclophosphamide to avoid impairing cyclophosphamide-induced tolerance.14 Once patients achieve therapeutic trough levels and are able to tolerate oral medications, tacrolimus is converted to an equivalent oral dose (1:3–4) divided every 12 h. This flat tacrolimus dose was implemented at this center over 10 years ago based on clinical experience and continues to be the institutional standard of practice due to demonstrated outcomes.14,15,16 The rates of grades II–IV aGVHD and cGHVD with this prophylaxis regimen have been shown to be 34% and 5%, respectively. Graft rejection has been observed in 13% of patients receiving this regimen following haploidentical nonmyeloablative alloHSCT.14

The primary objective of this study was to collect and analyze the initial tacrolimus serum concentrations achieved using a starting dose of 1 mg IV daily. Secondary objectives included ascertaining the dose, duration of therapy and number of dose changes necessary to achieve a therapeutic steady state concentration, and identifying patient-specific factors that influence the therapeutic tacrolimus dose. Furthermore, the number of days of therapy needed to achieve a therapeutic blood concentration and the incidence of both GVHD and graft failure were assessed to determine if a relationship existed.

Methods

A retrospective chart review included adult patients who received tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis following alloHSCT from 1 January 2012 through 31 December 2012 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Each tacrolimus blood concentration measured from transplant day +5 at tacrolimus initiation, until the patients achieved their first therapeutic trough level (10–15 ng/ml) was captured. If a supratherapeutic level (>15 ng/ml) was measured prior to achieving a trough in the therapeutic range, that level was recorded and data collection continued until a therapeutic level was achieved. A trough was defined as a concentration measured at least 18 h after the previous dose. If multiple troughs were measured on the same day, only the correctly timed level per this definition was considered.

The flat tacrolimus dose (in mg) needed to achieve a tacrolimus trough concentration of 10–15 ng/ml was defined as the therapeutic dose. The therapeutic dose as also recorded as a weight-based dose using actual (ABW), 20% adjusted (AdjBW) for patients with a BMI ≥30, ideal (IBW) and lean body weight (LBW) by dividing the aforementioned therapeutic dose by these respective body weights. The number of days of tacrolimus therapy needed to achieve a therapeutic tacrolimus level was defined as the number of days from the day of tacrolimus initiation until the day of the first therapeutic trough. Laboratory data collected on the day of tacrolimus initiation (alloHSCT day +5) and the day of the first therapeutic trough value included serum creatinine, albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. If lab values were not reported on the day of interest, laboratory values drawn within 48 h of the day of interest were recorded. Concomitant use of at least one dose of interacting medications known to affect tacrolimus concentrations (Appendix 1) from the day tacrolimus was initiated until the first therapeutic level was achieved was noted. Demographic information including age, gender, race, height, ABW, IBW, LBW and AdjBW, indication for transplant, HLA status (matched versus haploidentical), and pre-transplant preparation chemotherapy regimen were captured. Outpatient clinic notes were reviewed, and presence of a GVHD diagnosis by days +60 and +180 was recorded. Peripheral blood and/or bone marrow T-cell chimerism results were reviewed to assess for graft failure at day +60. Patients with detected donor DNA ≤5% were considered to have graft rejection.

Eligible patients included adult inpatients and out-patients seen in the Inpatient/Outpatient (IPOP) bone marrow transplant clinic who were initiated on tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis following alloHSCT from 1 January 2012 through 31 December 2012. Patients admitted for treatment of active GVHD and patients in whom tacrolimus therapy was discontinued or converted to oral therapy prior to achieving a therapeutic concentration were excluded.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the baseline demographics of the patient population. The initial serum tacrolimus levels achieved were characterized using descriptive statistics for the first tacrolimus level using the standard dose of 1 mg IV daily. Results were reported using both continuous (median, interquartile range) and categorical (subtherapeutic, therapeutic, and supratherapeutic) formats. The tacrolimus dose per kilogram of ABW, IBW, LBW and AdjBW necessary to achieve a therapeutic steady state concentration was characterized using descriptive statistics (median, interquartile range) as were the number of days of tacrolimus therapy and number of dose changes needed to achieve a therapeutic trough. To identify patient-specific factors influencing the tacrolimus dose needed to achieve a therapeutic serum concentration, simple linear regression was used. If factors were found to be statistically significant, they were to be analyzed using a multivariate linear regression to adjust for confounding. The alternative body weight with the strongest regression coefficient was considered to be the most appropriate dosing weight and was to be included in the multivariate linear regression model. Logistic regression was used to relate the diagnosis of GVHD and graft failure with the number of days needed to achieve a therapeutic tacrolimus blood concentration. Stata® Statistical Analysis and Statistical Software was used to perform data analysis. Graphical analyses were used to further explore the collected data.

Results

A total of 99 patients met the criteria for inclusion in this study (Table 1). The majority of patients were Caucasian (n =83, 84%) males (n =66, 67%) with a median age of 58 years (IQR = 19). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) were the most common diagnoses, comprising 36% (n =36) and 31% (n =31) of the study population, respectively. The majority of patients received a non-myeloablative conditioning regimen (n =74, 75%) as part of a haploidentical alloHSCT (n =94, 95%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Age, yrs | |

| Range | 21–74 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 58 (19) |

| Gender, n(%) | |

| Male | 66 (67%) |

| Female | 33 (33%) |

| Race, n(%) | |

| Caucasian | 83 (84%) |

| African American | 13 (13%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 2 (2%) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (1%) |

| BMI | |

| Range | 18.13–41.70 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 27.25 (7) |

| Obese, n(%) | |

| BMI ≥30 | 29 (29%) |

| Diagnosis, n(%) | |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 36 (36%) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 31 (31%) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 8 (8%) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 6 (6%) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 6 (6%) |

| Non-malignant disorders | 4 (4%) |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 4 (4%) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 (4%) |

| HLA status, n(%) | |

| HLA-haploidentical | 94 (95%) |

| HLA-matched | 5 (5%) |

| Type of transplant, n(%) | |

| Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical | 70 (71%) |

| Nonmyeloablative HLA-matched | 5 (5%) |

| Myeloablative HLA-haploidentical | 24 (24%) |

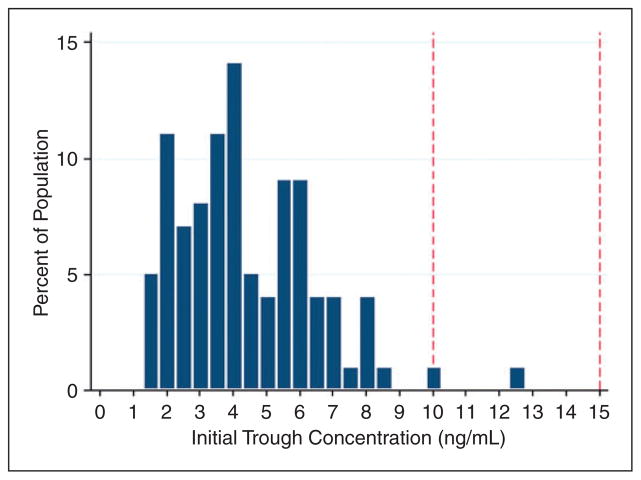

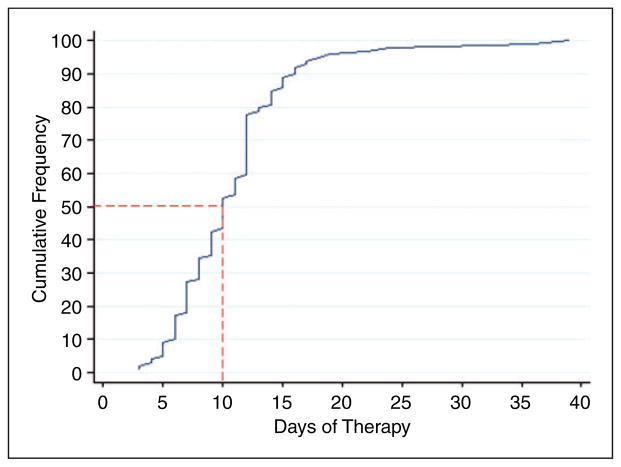

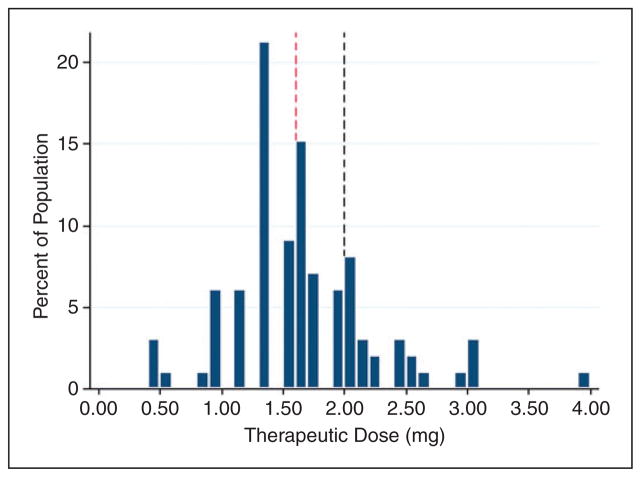

An initial tacrolimus trough serum concentration was drawn on a median of transplant day +7 (IQR =1), or after two doses of tacrolimus 1 mg IV daily. At the time their first level was drawn, 97 patients (98%) were subtherapeutic with a median initial trough of 4.0 ng/ml (IQR =2.8) (Figure 1). Patients required a median of 10 days (IQR =5) of IV tacrolimus, with a median of two dose changes (IQR =2), in order to achieve a therapeutic trough (Figure 2). None of the patients had a supratherapeutic trough recorded prior to achievement of a therapeutic trough. Patients became therapeutic on a median IV tacrolimus dose of 1.6 mg (IQR =0.06) daily (Figure 3), with a cumulative percentile of 75% of the population reaching a therapeutic concentration at a dose of 2 mg IV daily.

Figure 1.

Initial serum concentrations achieved using current tacrolimus dosing strategy. Plasma trough concentrations achieved after a median of two doses of IV tacrolimus. The target plasma concentration range of 10–15 ng/ml is outlined by the red dashed lines.

Figure 2.

Days of IV therapy required to achieve a therapeutic level. The red dashed lines indicate the median number of days of tacrolimus IV therapy necessary prior to achieving a therapeutic trough.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic dose requirement. The median therapeutic dose is indicated by the red dashed line (1.6 mg IV). The dose necessary for 75% of patients to achieve a therapeutic trough concentration (2 mg IV) is indicated by the black dashed line.

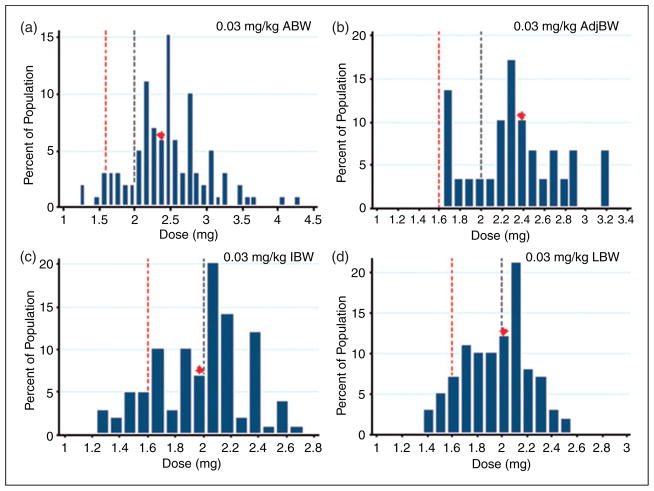

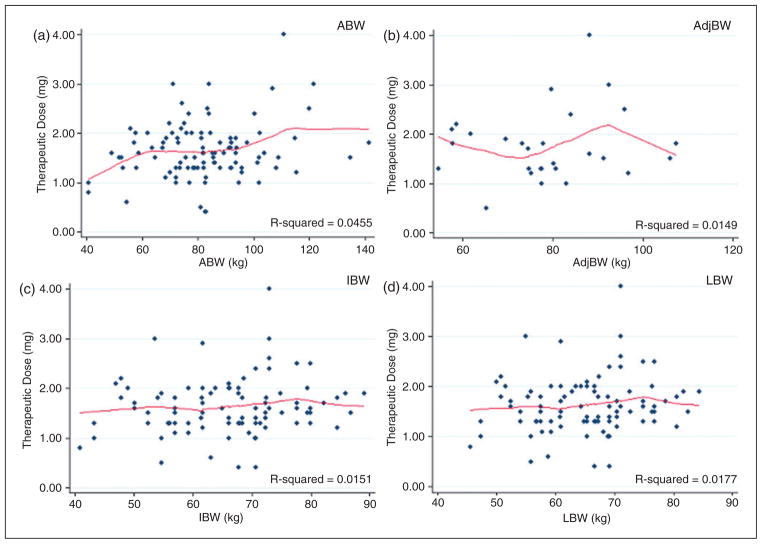

Because most centers initiate patients on a weight-based dose, projected initial tacrolimus doses using 0.03 mg/kg were calculated for each body weight of interest as a point of reference (Figure 4). If measured as a weight-based dose, the median therapeutic dose required by this study group was 0.019 mg/kg ABW (IQR =0.011), 0.023 mg/kg IBW (IQR =0.029), 0.023 mg/kg LBW (IQR =0.011), or 0.023 mg/kg 20% AdjBW (IQR =0.016). However, there was no association between ABW, IBW, LBW, or AdjBW with therapeutic dose in this patient population (Figure 5). None of the patient-specific factors tested, including total bilirubin, serum creatinine, albumin, race, gender, or concomitant azole therapy were found to correlate with the tacrolimus dose needed to reach a therapeutic blood concentration (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Projected weight-based initial dosing. Projected initial tacrolimus doses for the patients in the current study had they been initiated on a weight-based dose. (a) Projected doses based on ABW, (b) AdjBW, (c) IBW and (d) LBW, respectively. Regardless of the weight basis used, all patients would have been initiated on a dose >1 mg IV. The median projected dose is indicated by the red diamond. The highest median initial dose was calculated using AdjBW (b). The red dashed line indicates the median therapeutic dose determined by the current study (1.6 mg IV) and the black dashed line indicates the dose that resulted in a therapeutic trough concentration for at least 75% of patients studied.

Figure 5.

Relationship between weight and therapeutic dose requirement. Linear regression analyses for each body weight assessed versus therapeutic dose are shown with the corresponding regression coefficient. (a) The relationship between therapeutic dose with ABW, (b) AdjBW, (c) IBW and (d) LBW, respectively. Regardless of the weight basis tested, no relationship was seen between weight and therapeutic dose.

Table 2.

Impact of patient-specific factors on therapeutic dose.

| Factor | R-squared |

|---|---|

| Age | 0.0268 |

| Gender | 0.0002 |

| Race | 0.0206 |

| Body mass index | 0.0445 |

| Indication for chemotherapy | 0.0104 |

| HLA status | 0.0000 |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.0430 |

| Serum creatinine, transplant day +5 | 0.0073 |

| Albumin, transplant day +5 | 0.0231 |

| Total bilirubin, transplant day +5 | 0.0003 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, transplant day +5 | 0.0113 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, transplant day +5 | 0.0075 |

| Concomitant azole therapy | 0.0070 |

Note: Patient-specific factors analyzed for association with therapeutic dose and the corresponding regression coefficient.

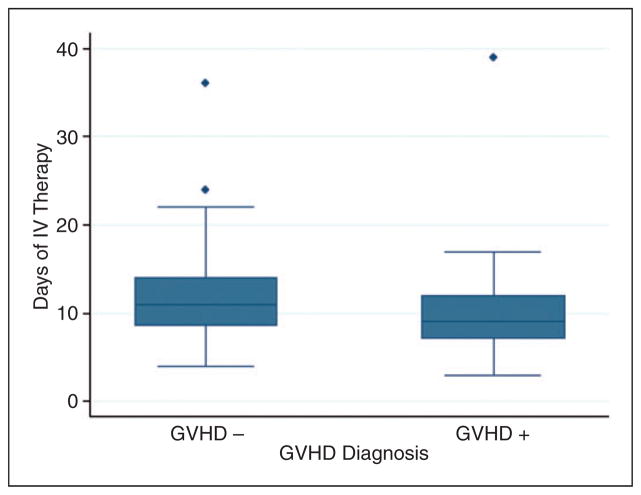

A cumulative total of 38 patients (40%) had documented GVHD within the first 180 days post-transplant. Active GVHD was noted by day 60 in 21 patients (21%) and day 180 in 17 patients (17%). This study did not show a relationship between the number of days of tacrolimus therapy needed to reach a therapeutic concentration and the incidence of GVHD during the first 180 days post-transplant (Figure 6). Of note, 20 patients (20%) passed away or were lost to follow-up prior to day 180 omitting them from the GVHD analysis. One patient (1%) had documented graft failure at day +60. Two patients passed away prior to day +60 and were omitted from the graft failure analysis.

Figure 6.

Development of GVHD. Number of days of IV therapy necessary to achieve a therapeutic trough concentration in patients diagnosed with GVHD (GVHD +) within the first 180 days post-alloHSCT compared to the days of IV therapy necessary in patients not diagnosed with GVHD (GVHD −).

Discussion

The current practice to initiate all patients on tacrolimus 1 mg IV daily as a 4 h infusion on transplant day +5 leads to 98% of patients having subtherapeutic troughs at the time of their initial measurement according to our institution’s target range of 10–15 ng/ml. Notably, the institution’s target range was increased from 5–15 ng/ml to 10–15 ng/ml prior to the study period in order to increase successful engraftments. Participants of a 1999 consensus conference agreed on a target trough range of 10–20 ng/ml, further demonstrating a wide range of therapeutic values amongst institutions.17

Many centers throughout the United States initiate tacrolimus using a weight-based dose. A starting dose of 0.03 mg/kg is commonly utilized in outcomes studies in the literature; however, data supporting this dosing practice are limited.4,8,11,18 This recommended dose is higher than the median calculated weight-based dose required by patients in this study. Interestingly, no relationship between weight and therapeutic tacrolimus dose was detected (Figure 5). In addition to weight, no patient-specific factors were linked with dose requirement, including age, gender, race, BMI, diagnosis, conditioning chemotherapy regimen, HLA match status, serum creatinine, albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and concomitant azole antifungal therapy.

A flat initial tacrolimus dose may be the optimal approach in the hematopoietic stem cell transplant population given the lack of correlation between weight and therapeutic dose observed in this study. This dose must balance achieving therapeutic troughs quickly while limiting toxic side effects (e.g. nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity and hyperkalemia). One proposed dosing strategy would be to initiate all patients on the median therapeutic dose of 1.6 mg IV daily. This dose is expected to allow half of the patients at this center to achieve the therapeutic range of 10–15 ng/ml at the time of their first steady state blood concentration on transplant day +8. A second proposed dosing strategy is to initiate all patients on a flat dose of 2 mg IV daily. This dose is expected to allow roughly 75% of patients to achieve a therapeutic trough by transplant day +8. While it is not possible to accurately predict the number of patients who may become supratherapeutic on these proposed initial doses, both are less than or equal to the median initial projected dose for each body weight (actual, lean, ideal, or adjusted) tested, suggesting safety and tolerability (Figure 4). The results of this study are hypothesis-generating. As of February 2015, the institutional standard of practice was changed to initiate tacrolimus at a flat dose of 1.6 mg IV daily over 4 h. Further studies will be conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of initiating tacrolimus at a higher flat dose.

While this study failed to identify a link between the duration of time spent below the therapeutic range and the incidence of GVHD, other studies have indicated a relationship, particularly in unrelated donor transplants.5 Additional factors, including patient adherence and other immunosuppression agents used, should be considered when evaluating the incidence of GVHD. Importantly, the small sample size in this study limited the ability to assess this relationship with certainty. Further studies of this relationship are warranted.

This study was also unable to identify a relationship between the number of days of therapy needed to reach a therapeutic trough with the incidence of graft failure as only one patient was determined to have rejection at day +60. This patient received a myeloablative haploidentical alloHSCT and required eight days of IV tacrolimus prior to achievement of a therapeutic trough. Further studies of this relationship are also warranted given the small sample size studied.

Results of this study are limited by its retrospective design. Additionally, there was limited demographic diversity within the study population and some patients expired or were lost to follow-up prior to day +180, omitting them from the GVHD incidence analysis. Finally, results may be limited to patients receiving the combination of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide for GVHD prophylaxis, or to patients undergoing nonmyeloablative haploidentical conditioning regimens as these patients made up the majority the study population.

Results of this study warrant further investigation into tacrolimus dosing strategies in alloHSCT patients. A multicenter, retrospective review would overcome some of the limitations of this study and help to elucidate relationships between patient-specific factors and therapeutic tacrolimus dose. Such a study would, however, be complicated by non-standardized target troughs and dosing practices amongst institutions.

Conclusion

An initial flat tacrolimus dose of 1 mg IV daily is a suboptimal dosing strategy in terms of initial plasma concentration achieved and duration of therapy required to reach a therapeutic trough in alloHSCT patients at this institution. No patient-specific factors were found to correlate with therapeutic dose. Because weight was not found to correlate with therapeutic dose, the results of this study support initiating patients on a flat dose. An initial dose of tacrolimus 1.6 mg IV or 2 mg IV daily are reasonable alternatives to the current institutional standard of practice and warrant further studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Haley Gibbs, PharmD, BCPS and Kenneth Shermock, PharmD, PhD (The Johns Hopkins Hospital) for their assistance with statistical analysis.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix 1. Medications used in alloHSCT known to interact with tacrolimus

| Mechanism | Drug | Onset | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs known to increase tacrolimus blood concentrations | |||

| Major | |||

| 3A4 inhibition | Voriconazole | Not specified | Decrease dose to 1/3 |

| Fluconazole | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Itraconazole | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Posaconazole | Not specified | Decrease dose to 1/3 | |

| Clarithromycin | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Atazanavir | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Omeprazole | Not specified | Avoid co-administration, reduce dose as needed | |

| Esomeprazole | Not specified | Avoid co-administration, reduce dose as needed | |

| Erythromycin | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Telaprevir | Rapid | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Nelfinavir | Not specified | Avoid co-administration, reduce dose as needed | |

| Telithromycin | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Amiodarone | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Nilotinib | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| 3A4 and P-gp inhibition | Darunavir | Not specified | Decrease dose to 50% |

| Ranolazine | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Moderate | |||

| 3A4 inhibition | Nifedipine | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed |

| Clotrimazole | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Theophylline | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Amprenavir | Delayed | Monitor closely | |

| Ketoconazole | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Diltiazem | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Lansoprazole | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Felodipine | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Indinavir | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Deavirdine | Delayed | Monitor closely | |

| Cisapride | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Ethinyl estradiol | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Nicardipine | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Bromocriptine | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Dexlansoprazole | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Verapamil | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Cimetidine | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Metronidazole | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Improved gastric motility | Metoclopramide | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed |

| Reduced metabolism | Methylprednisolone | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed |

| Unknown | Tigecycline | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed |

| Danazol | Delayed | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Teduglutide | Not specified | Decrease dose as needed | |

| Bosentan | Not specified | Use caution | |

| Tinidazole | Not specified | Use caution | |

| Drugs known to decrease tacrolimus blood concentrations | |||

| Major | |||

| 3A4 induction | St. Johns’ Wort | Delayed | Discontinue supplement |

| Phenytoin | Delayed | Increase dose as needed | |

| Phenobarbital | Delayed | Increase dose as needed; switch to a non-CYP inducing anticonvulsant or lower dose | |

| Efavirenz | Not specified | Increase dose as needed | |

| Primidone | Not specified | Avoid co-administration | |

| Etravirine | Not specified | Increase dose as needed | |

| Carbamazepine | Delayed | Increase dose as needed | |

| Rifabutin | Delayed | Increase dose as needed | |

| 3A4 and P-gp induction | Rifampin | Delayed | Increase dose as needed |

| Unknown | Sirolimus | Delayed | Avoid co-administration, increase dose as needed |

| Caspofungin | Not specified | Increase dose as needed | |

| Moderate | |||

| 3A4 induction | Rifapentine | Delayed | Increase dose as needed |

| Nevirapine | Not specified | Increase dose as needed | |

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Zuckerman T, Rowe JM. Alternative donor transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia: which source and when? Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:152–161. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328017f64d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kernan NA, Collins NH, Juliano L, et al. Clonable T lymphocytes in T cell-depleted bone marrow transplants correlate with development of graft-v-host disease. Blood. 1986;68:770–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernan NA, Flomenberg N, Dupont B, et al. Graft rejection in recipients of T-cell-depleted HLA- nonidentical marrow transplants for leukemia. Identification of hostderived antidonor allocytotoxic T lymphocytes. Transplantation. 1987;43:842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallin JE, Friberg LE, Fasth A, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: new initial dosage suggestions and a model-based dosage adjustment tool. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31:457–466. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181aab02b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies JK, Lowdell MW. New advances in acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. Transfus Med. 2013;13:387–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2003.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SJ, Klein JP, Barrett AJ, et al. Severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease: association with treatment-related mortality and relapse. Blood. 2002;100:406–414. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the bone marrow transplant survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110:3784–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBlanc K, Remberger M, Uzunel M, et al. A comparison of nonmyeloablative and reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:1014–1020. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000129809.09718.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fay JW, Wingard JR, Antin JH. FK506 (Tacrolimus) monotherapy for prevention of graft-versus-host disease after histocompatible sibling allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;87:3514–3519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boswell GW, Bekersky I, Fay J, et al. Tacrolimus pharmacokinetics in BMT patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:23–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson P, Uberti J, Davis W, et al. Tacrolimus: a new agent for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:217–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staatz CE, Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:623–653. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingard JR, Nash RA, Przepiorka D, et al. Relationship of tacrolimus (FK506) whole blood concentrations and efficacy and safety after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1998;4:157–163. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.1998.v4.pm9923414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Symons HF, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell PV, Luznik L, Jones RJ, et al. Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation from partially HLA-mismatched related donors using posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8:377–386. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12171484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasamon Y, Luznik L, Leffell MS, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przepiorka D, Devine SM, Fay JW, et al. Practical considerations in the use of tacrolimus for allogeneic marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1053–1056. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanik G, Levine JE, Ratanatharathorn V, et al. Tacrolimus (FK506) and methotrexate as prophylaxis for acute graft-versus-host disease in pediatric allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:161–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]