Abstract

The oncogenic transcription factor FOXM1 is overexpressed in the majority of human cancers, and it is a potential target for anticancer therapy. We identified proteasome inhibitors as the first type of drugs that target FOXM1 in cancer cells. Here we found that HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847 and heat shock also suppress FOXM1. The common effector, which was induced after treatment with proteasome and HSP90 inhibitors or heat shock, was the molecular chaperone HSP70. We show that HSP70 binds to FOXM1 following proteotoxic stress and that HSP70 inhibits FOXM1 DNA-binding ability. Inhibition of FOXM1 transcriptional autoregulation by HSP70 leads to the suppression of FOXM1 protein expression. In addition, HSP70 suppression elevates FOXM1 expression, and simultaneous inhibition of FOXM1 and HSP70 increases the sensitivity of human cancer cells to anticancer drug-induced apoptosis. Overall, we determined the unique and novel mechanism of FOXM1 suppression by proteasome inhibitors.

Keywords: 70-kD heat shock protein (Hsp70), anticancer drug, cell death, gene expression, protein-protein interaction, FOXM1

Introduction

Forkhead Box M1 (FOXM1) is an oncogenic transcription factor that is also a well recognized cell cycle regulator (1). FOXM1 expression is eliminated from quiescent or differentiated cells, but it is highly expressed in proliferating and malignant cells (1). It is also well documented that FOXM1 is overexpressed in broad types of human cancers and it contributes to several aspects of cancer development (2, 3). Consequently, it is not surprising that FOXM1 has evolved as a potential target of anticancer therapy (4).

Our group identified the thiazole antibiotics Siomycin A (5) and thiostrepton (6) as the first chemical inhibitors of FOXM1. Investigation of their mechanism of action revealed that they are proteasome inhibitors (7). Bona fide proteasome inhibitors, including MG132 and bortezomib, have also been found to hinder the transcriptional activity and expression of FOXM1 (7), suggesting that FOXM1 is one of the general targets of these drugs. Proteasome inhibitors stabilize the expression of cellular proteins. Therefore, suppression of FOXM1 is counterintuitive and has not been well understood. As an explanation for this effect, we put forward the hypothesis that a negative regulator of FOXM1 (NRFM)2 is stabilized by proteasome inhibitors (8), which directly or indirectly inhibits FOXM1 transcriptional activity (9). Here we determined that the NRFM is HSP70. Because a positive autoregulation loop is required for FOXM1 expression (9), HSP70 (NRFM) also represses FOXM1 mRNA and protein expression after treatment with proteasome inhibitors.

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are stress proteins that are mainly expressed in response to different cellular and environmental insults. HSPs are divided by their molecular weight into the subfamilies HSP110, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, and small HSPs. Besides their major function of aiding protein folding as molecular chaperones, HSPs also play important roles in cell signaling, protein trafficking, and blocking cell death (10–13). Elevated levels of HSPs are linked not only to cytoprotection but to neurodegenerative disorders and cancer (10, 12). Among the several members of the HSP70 family, HSC70 is constitutively expressed under non-stressful conditions as well, whereas the expression of stress-inducible HSP70 is mainly detectable following different types of stress (11, 12). Overexpression of anti-apoptotic HSP70 is often seen in human cancers. Therefore, targeting HSP70 has emerged as a tempting approach to improve anticancer therapy (12). However, our current findings suggest that caution should be employed with the incorporation of HSP70 inhibitors into chemotherapeutic drug combinations for the treatment of cancer because they lead to the induction of oncogenic transcription factor FOXM1.

In this study, we identified HSP70 as the negative regulator of FOXM1 after proteotoxic stress. We demonstrate that treatment with proteasome and HSP90 inhibitors or heat shock results in decreased FOXM1 and increased HSP70 protein expression. We also show that following proteotoxic stress FOXM1 and HSP70 bind to each other. We concluded that HSP70 negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of FOXM1 by interfering with the DNA-binding ability of FOXM1. Because of FOXM1 autoregulation, HSP70 also inhibits FOXM1 expression. In addition, we demonstrate that the combination of FOXM1 and HSP70 inhibitors increases the sensitivity of human cancer cells to cell death. Our results reveal a novel regulatory function of HSP70 after proteotoxic stress.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Chemical Compounds

DU145 prostate, MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell lines (ATCC), and U2OS osteosarcoma and osteosarcoma-derived C3 (14) and C3-luc cells (5) were grown in DMEM (Cellgro). The MDA-MB-231 (ATCC) breast and RPMI 8266 multiple myeloma cancer cell lines were grown in RPMI medium (Cellgro). The media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Bortezomib (Velcade, Millennium Pharmaceuticals), thiostrepton (Sigma), PF-4942847 (Pfizer), 9-aminoacridine (9AA, Fluka) and quercetin (Sigma) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Fisher Scientific), and doxycycline (LKT Laboratories) was dissolved in PBS.

Immunoblot Analysis

Treated cells were harvested and lysed by using IP buffer (20 mm HEPES, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 100 mm NaF, 10 mm Na4P2O7, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 0.2 mm PMSF supplemented with a protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Applied Sciences)). Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad protein assay. Isolated proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). Immunoblotting was carried out with antibodies specific for FOXM1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; the rabbit polyclonal antibody against FOXM1 has been described previously (15)), HSP70 3a3 and 2A4 (gifts from Dr. Morimoto), cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (Sigma).

Plasmids, siRNAs, and Transfection

The FOXM1 expression plasmid was a gift from the late Dr. Robert H. Costa, and the HSP70 expression plasmid was purchased from Addgene (plasmid 15215, Ref. 16). Control (universal negative control 1) siRNAs and siRNAs specific to HSP70 (17–19) and FOXM1 (GGACCACUUUCCCUACUUUUU) were synthesized by Sigma. Transient transfections were carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the recommendation of the manufacturer. Cells were processed as described in the figure legends after transfection.

IP

Cells were harvested, lysed in IP buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, and protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. Between 200 and 400 μg of lysates in a 500-μl volume were precleared by incubation with 1 μg of rabbit IgG and 30 μl of protein A-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) on a rotary mixer for 30 min at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged for 1 min at 1000 rpm, and the clarified lysates were transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes. 2 μg of FOXM1 antibody and 30 μl of protein A-agarose were added, and the samples were incubated on a rotary mixer overnight at 4 °C. The agarose beads were washed four times with IP buffer containing protease inhibitors and centrifuged for 1 min at 1000 rpm at 4 °C each time. The beads were then resuspended in 100 μl of 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad), boiled, and centrifuged, and then the supernatant was separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted with FOXM1- and HSP70-specific antibodies.

Flow Cytometry: Propidium Iodide Staining

Cells were treated as indicated and harvested by trypsinization. Then cells were washed in PBS and fixed in ice-cold 95% ethanol. Following fixation, cells were stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) (Invitrogen) in PBS/RNase A/Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature and analyzed by flow cytometry.

ChIP

ChIP was performed as described in Ref. 20 with the following modifications. A total of 8 × 106 U2OS-derived C3 cells were used per IP. The input corresponded to 1/50 part of the IP. 5 μg of FOXM1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was bound to 30 μl of Dynabead protein G (Invitrogen) and added to each IP. The amount of DNA from the IP and from the input in the PCR reaction corresponded to 500 pg/μl. Quantitative PCR reactions contained 2.5 μl of SYBR Green Mix (Bio-Rad), 1.25 μl of 4 μm primer pair mixture, and 1.25 μl of the DNA template. The following primers were used to amplify the indicated human gene promoter fragments: AURKB forward, 5′-AGATGGCTGGTGTTCCAATGTAGC-3′; AURKB reverse,5′-TTCTTTCCGTTGCTCAGACTCCCA-3′; CDC25B forward, 5′-TGGGCGTGATACTTAATTCGCCTC-3′; CDC25B reverse, 5′-AGGCTCTAAACGGTGGAACTAGGA-3′; FOXM1_1forward, 5′-CACTATGCCCAGCCCACATTTGTT-3′; FOXM1_1 reverse, 5′-AGGCCCTGAAGATACAATGGCAGA-3′; FOXM1_2 forward, 5′-AGCCCGGAATGCCGAGACAA-3′; FOXM1_2 reverse, 5′-GTTCCGCTGTTTGAAATTGGCG; FOXM1_3 forward, 5′-GCTATCCCATCCATTTCTGTAGCC-3′; and FOXM1_3 reverse, 5′-GCAGACAGAAGCAATTCAAAGGGC-3′. The quantitative PCR was run on a Bio-Rad CFX thermocycler using the following quantitative PCR protocol: 98 °C for 1:30 min, 98 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 30 s, cycle 39 times steps 2–4, 95 °C for 30 s, and melt curve 55–95 °C in 0.5 °C increments for 30 s. The baseline threshold was set up manually 15.90 for each plate. Enrichment was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method, and results are presented as percent of input.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post test or unpaired t test. p values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

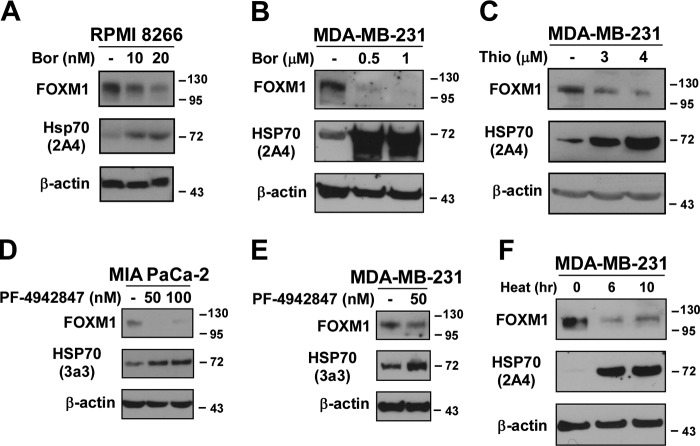

FOXM1 Protein Expression Is Suppressed, whereas HSP70 Protein Expression Is Elevated following Proteotoxic Stress

We have found previously that FOXM1 is down-regulated (7), whereas it is known that HSP70 is up-regulated after treatment with proteasome inhibitors (21). To confirm this observation, multiple myeloma (RPMI 8266) and breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) were treated with the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib or thiostrepton (Fig. 1, A–C). We found that following treatment with the proteasome inhibitors FOXM1 suppression correlated with HSP70 up-regulation. Because inhibition of HSP90 leads to the up-regulation of HSP70 (12), we wanted to determine whether treatment with HSP90 inhibitors also represses FOXM1. MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated with the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847, and FOXM1 was detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 1, D and E). We found that a decrease in FOXM1 expression was indeed linked to an increase in HSP70 expression following treatment with the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847. In agreement with previous studies, we also confirmed that the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847 is not a proteasome inhibitor (data not shown). Therefore, it induces HSP70 (Fig. 1, D and E) by a mechanism different from proteasome inhibitors. Because both proteasome inhibitors and the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847 up-regulated HSP70 and suppressed FOXM1, it suggests that after proteotoxic stress the down-regulation of FOXM1 by HSP70 is a universal mechanism. Additionally, when breast (MDA-MB-231) cancer cells were subjected to heat shock, we also observed that the induction of HSP70 correlated with the suppression of FOXM1 (Fig. 1F). These data suggest that HSP70 might negatively regulate FOXM1 during proteotoxic stress.

FIGURE 1.

Treatment with proteasome and HSP90 inhibitors or heat shock leads to the down-regulation of FOXM1 and the up-regulation of HSP70. A–C, RPMI 8266 multiple myeloma and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib (Bor) or thiostrepton (Thio) as indicated. Twenty-four hours after treatment, cells were harvested, and immunoblotting was carried out with antibodies against FOXM1 and HSP70. β-Actin was used as the loading control. D and E, MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847. Cells were harvested 24 h after treatment, and the protein levels of FOXM1 and HSP70 were assessed by immunoblotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. F, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were subjected to heat shock at 42 °C for the indicated time points. Following treatment, cells were harvested, and immunoblotting was performed for FOXM1, HSP70, and β-actin as the loading control.

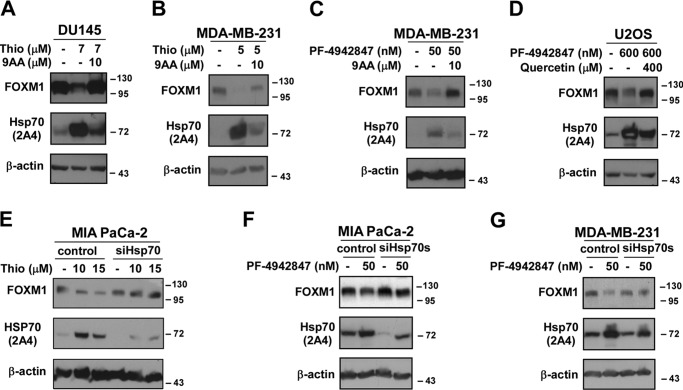

Inhibition of HSP70 Alleviates FOXM1 Suppression during Proteotoxic Stress

To evaluate the role of HSP70 in the negative regulation of FOXM1 during proteotoxic stress, we inhibited HSP70 using drugs and RNAi. Prostate (DU145), breast (MDA-MB-231), and osteosarcoma (U2OS) cells were treated with thiostrepton or PF-4942847 in the presence and absence of the HSP70 inhibitors 9AA or quercetin, which are commonly used to inhibit HSP70 (10–12, 24). Western blotting showed that inhibition of HSP70 led to the restoration of FOXM1 protein level to basal level following treatment with the proteasome inhibitor thiostrepton or the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847 (Fig. 2, A–D). Because both 9AA and quercetin are not specific inhibitors of HSP70, we also utilized RNAi against HSP70. Similarly to the pharmacological inhibitors of HSP70, RNAi-mediated knockdown of HSP70 in pancreatic and breast cancer cells restored the protein expression of FOXM1 after thiostrepton or PF-4942847 treatment (Fig. 2, E–G). These data suggest that HSP70 suppresses FOXM1 during proteotoxic stress.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of HSP70 restores the protein expression of FOXM1. A–D, DU145 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thiostrepton (Thio) in combination with the HSP70 inhibitor 9AA. MDA-MB-231 and U2OS cells were treated with the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847 along with the HSP70 inhibitor 9AA or quercetin, respectively. Twenty-four hours after treatment, cell lysates were immunoblotted for FOXM1, HSP70, and β-actin as the loading control. E–G, MIA PaCa-2 and MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with control and HSP70 siRNAs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of thiostrepton or the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847. Immunoblot analysis was performed for FOXM1, HSP70, and β-actin as the loading control.

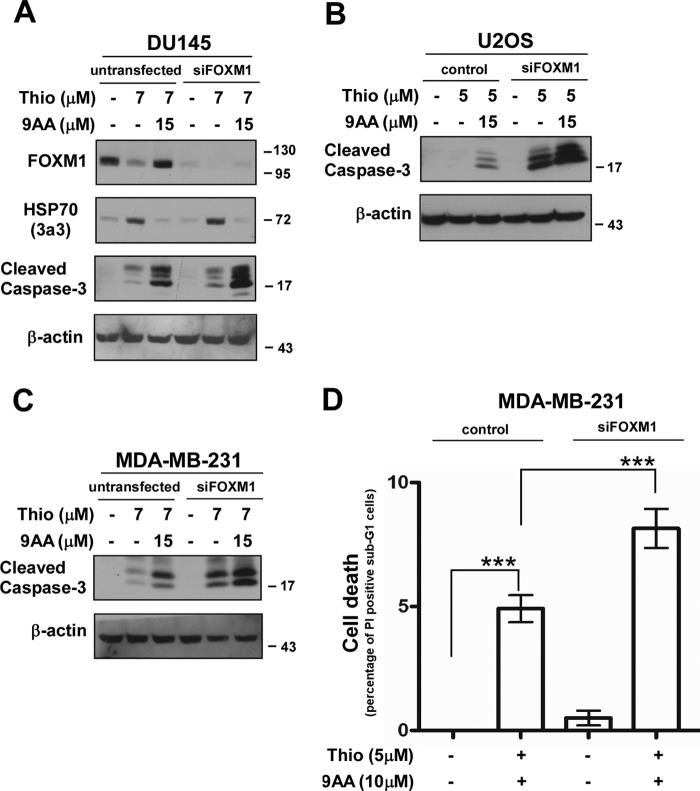

Inhibition of HSP70 in Combination with Suppression of FOXM1 Promotes Apoptosis of Human Cancer Cells

HSP70 can block both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways at different levels. Consequently, inhibition of HSP70 is believed to counteract its anti-apoptotic functions and make cells more sensitive to cell death (10–12). However, according to our current findings, HSP70 inhibition leads to the up-regulation of FOXM1 (Fig. 2). FOXM1 is also known to confer resistance to apoptosis induced by various drugs, including proteasome inhibitors, Herceptin, paclitaxel, cisplatin, and epirubicin (25–28). Consequently, FOXM1 suppression increased the sensitivity of cancer cells to different cell death-inducing stimuli (3, 4).

We were interested whether concurrent inhibition of FOXM1 and HSP70 make cancer cells more prone to cell death. Transient FOXM1 knockdown cells were treated with thiostrepton in the presence or absence of the HSP70 inhibitor 9AA. Apoptosis was assessed by immunoblotting for cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 3, A–C) and by flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining (Fig. 3D). In agreement with earlier studies (10–12), we also observed that HSP70 inhibition sensitized cancer cells to cell death, in this case to thiostrepton-mediated apoptosis. But cancer cells with FOXM1 knockdown in the presence of the HSP70 inhibitor 9AA were more sensitive to cell death induced by thiostrepton (Fig. 3). These data suggest that simultaneous suppression of FOXM1 and HSP70 could be greatly beneficial for cancer treatment to circumvent any drug-related resistance.

FIGURE 3.

Simultaneous suppression of FOXM1 and HSP70 sensitizes human cancer cells to programmed cell death. A–C, transient FOXM1 knockdown cells and their control counterparts were treated with thiostrepton (Thio) in the presence or absence of the HSP70 inhibitor 9AA. Twenty-four hours after treatment, cell lysates were immunoblotted for FOXM1, HSP70, cleaved caspase-3, and β-actin as the loading control. D, MDA-MB-231 control and transient FOXM1 knockdown breast cancer cells were treated as indicated for 24 h. Cell death was determined by flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining. The graph shows quantification as the percentage of propidium iodide-positive sub-G1 cells compared with propidium iodide-positive sub-G1 control cells ± S.D. of a representative triplicate experiment. ***, p < 0.0001.

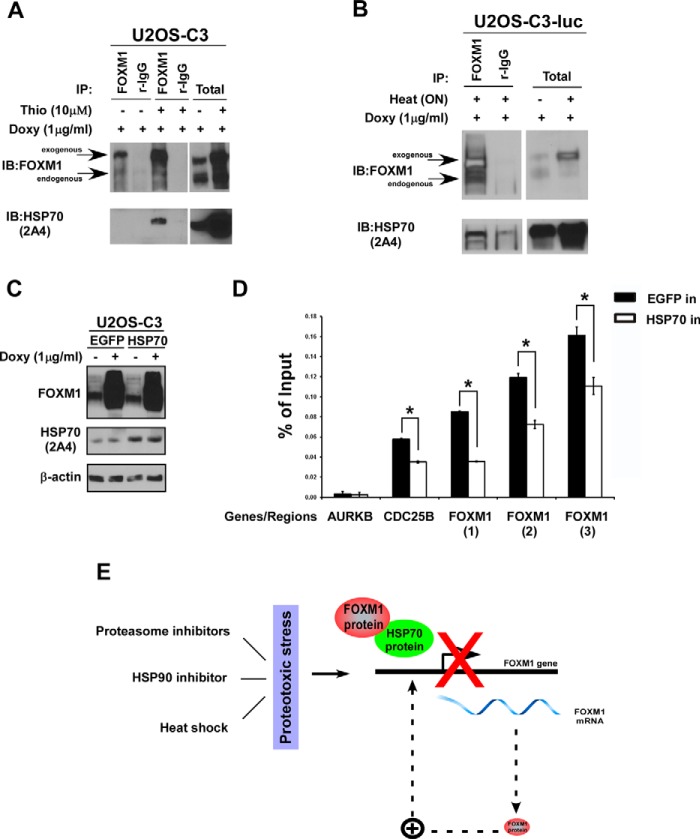

FOXM1 and HSP70 Interact with Each Other following Proteotoxic Stress

Because treatment with both thiostrepton and heat shock resulted in a low level of endogenous FOXM1 protein (Fig. 1), we took advantage of the tetracycline/doxycycline-inducible system to obtain high levels of exogenous FOXM1 (5), which is not affected by either stressor (data not shown). U2OS osteosarcoma-derived, tetracycline/doxycycline-inducible C3 cells (14) were treated with doxycycline and thiostrepton and immunoprecipitated with a FOXM1-specific antibody. Analysis of the TCA-acetone-purified immunoprecipitates by mass spectrometry suggested that FOXM1 interacts with HSP70 (data not shown).

To further confirm the binding between FOXM1 and HSP70, the U2OS-C3 (14) and U2OS-C3-luc cell lines (5) were treated with doxycycline and the proteasome inhibitor thiostrepton (Fig. 4A) or heat shock (Fig. 4B), respectively. Immunoprecipitations were performed with a FOXM1-specific antibody followed by immunoblotting for FOXM1 and HSP70. HSP70 co-immunoprecipitated with FOXM1 in both thiostrepton- and heat shock-treated cells (Fig. 4, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

HSP70 binds to FOXM1 and negatively regulates FOXM1 by interfering with the DNA-binding ability of FOXM1. A and B, C3 and C3-luc cells were induced with doxycycline (Doxy) and treated with thiostrepton (Thio) for 24 h or subjected to heat shock at 42 °C overnight. After treatment, the cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with the FOXM1 antibody or control rabbit IgG. Immunoblotting (IB) was performed with anti-FOXM1 and HSP70 antibodies. C, the C3 cell line was transiently transfected with the control enhanced GFP and the HSP70 expression plasmids. Doxycycline was added to the culture medium 48 h after transfection for an additional 24 h. Cells were harvested, and immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against FOXM1 and HSP70. β-actin was used as the loading control. D, the C3 cell line was transiently transfected with the control enhanced GFP (EGFP) and the HSP70 expression plasmids. Doxycycline was added to the culture medium 48 h after transfection for an additional 24 h. Cells were processed for the ChIP experiments as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The graph shows the mean ± S.E. of three independent ChIP experiments. *, p < 0.05. E, during proteotoxic stress, HSP70 expression increases, and it binds to FOXM1 and inhibits FOXM1 binding to its own regulatory elements, disrupting the autoregulation of FOXM1, which leads to the down-regulation of both FOXM1 mRNA and protein expression. Consequently, HSP70 acts as a negative regulator of FOXM1 after proteotoxic stress.

HSP70 Inhibits DNA-binding of FOXM1 to Its Own Regulatory Elements

In preliminary experiments, HSP70 inhibited the transactivation of a specific reporter by exogenous FOXM1 (data not shown). Because FOXM1 is involved in a positive autoregulatory loop in which it induces its own transcription, inhibition of FOXM1 transcriptional activity also leads to the down-regulation of its mRNA and protein levels (5, 9). Next we investigated the mechanism by which HSP70 inhibits the transcriptional activity of FOXM1. ChIP experiments were performed to determine whether HSP70 interferes with the binding of FOXM1 to its own regulatory elements and to the Cdc25B target gene promoter. A promoter region outside of the FOXM1 binding site of the direct transcriptional target Aurora B kinase was used as the negative control. The C3 cell line with stable expression of the doxycycline-inducible FOXM1-GFP fusion protein (14) was transiently transfected with the control enhanced GFP and the HSP70 expression plasmids. Forty-eight hours after transfection, FOXM1 expression was increased by doxycycline addition for 24 h, after which cells were processed for ChIP. These quantitative ChIP assays revealed that HSP70 reduces up to 2-fold the ability of FOXM1 to bind to its regulatory elements (Fig. 4D), whereas the level of exogenous FOXM1 was not affected (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that HSP70 interacts with FOXM1 and inhibits its DNA-binding activity.

Discussion

The oncogenic transcription factor FOXM1 is one of the most overexpressed genes in cancer (29), and it contributes to several aspects of oncogenesis (3), including metastasis in pancreatic (30) and liver cancer (31). Therapeutic targeting of FOXM1 is discussed widely in the literature, and a few years ago we identified proteasome inhibitors as the first chemical inhibitors of FOXM1 (5, 7). However, the mechanisms of FOXM1 suppression by proteasome inhibitors were not well understood. We previously proposed a hypothetical model for the suppression of FOXM1 by proteasome inhibitors. Proteasome inhibitors stabilize a negative regulator of FOXM1 (NRFM), which, in turn, inhibits the activity of FOXM1 as a transcription factor (8, 32). In this study, we identified the molecular chaperone HSP70 as the NRFM after proteotoxic stress (Fig. 4E). We determined that increased HSP70 protein expression correlates with decreased FOXM1 protein expression after exposure to proteotoxic stress (Fig. 1) and that inhibition of HSP70 up-regulates FOXM1 expression (Fig. 2). We demonstrated that HSP70 binds to FOXM1 (Fig. 4, A and B) and it inhibits FOXM1 DNA-binding to its promoter elements (Fig. 4D). As we have shown before, FOXM1 is involved in a positive feedback loop and activates its own transcription (9), so inhibition of FOXM1 transcriptional activity by HSP70 also leads to a decrease in its expression after proteotoxic stress (Figs. 1 and 4E). Recently, Cheng et al. (33) confirmed the importance of FOXM1 autoregulation for cancer development (34). They showed that the tumor suppressor SPDEF competed with FOXM1 for the FOXM1 binding site responsible for the autoregulation of FOXM1. Furthermore, SPDEF inhibited FOXM1 expression and consequently cancer development in a mouse model of prostate cancer (33). These data suggest that the autoregulation of FOXM1 might be required for cancer development and could be a promising target for anticancer treatment.

Suppression of FOXM1 (22, 23) and accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates (35) are two of the accepted hallmarks of proteasome inhibition. Here we confirm that HSP90 inhibitors are not proteasome inhibitors because they do not induce the accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates (data not shown). However, they target FOXM1 (Fig. 1, D and E), suggesting that they belong to a novel class of FOXM1 inhibitors. Both proteasome and HSP90 inhibitors up-regulate HSP70 and suppress FOXM1, supporting the idea that HSP70 is the universal NRFM that inhibits FOXM1 after proteotoxic stress.

Under normal conditions, HSP70 accumulates after stress to protect cells from adverse effects, therefore promoting cell survival. However, high levels of HSP70 are also often found in different types of cancer, providing protection against cell death and resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Therefore, HSP70 appeared as one of the important targets to improve the outcomes of anticancer therapy, and the search for inhibitors of HSP70 has been on the rise (12). However, this work calls for caution in respect to the prospective administration of HSP70 inhibitors to cancer patients in the future. We showed that inhibition of HSP70 leads to the up-regulation of the oncogenic transcription factor FOXM1 (Fig. 2) and that FOXM1 knockdown cancer cells in the presence of the HSP70 inhibitor 9AA became more sensitive to apoptosis (Fig. 3). Consequently, these findings strongly support the combination of novel types of FOXM1 and HSP70 inhibitors to avoid detrimental effects and to achieve a more effective therapeutic strategy for the successful treatment of cancer.

Several parallels exist between FOXM1 and HSP70. Both are overexpressed and considered to be oncogenic in different types of cancer, and their elevated expression is associated with a poor prognosis for cancer patients. Increased expression of both makes cancer cells resistant to cell death and chemotherapeutic drugs, and both have emerged as attractive targets of anticancer therapy (3, 4, 12, 36). Altogether, according to the existing literature, both FOXM1 and HSP70 are oncogenes. Also, the authors of a recent review on HSP70 argued that HSP70 might contribute to cancer development by regulating multiple signaling pathways, such as HIF1-α and NF-κB (36). However, according to our findings, by inhibiting the FOXM1 oncogene, HSP70 can also act as a tumor suppressor. Taken together, our current data suggest that HSP70 belongs to the group of proteins with “antagonistic duality” (37), including c-myc and p21, which depending on the circumstances may act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors.

Author Contributions

M. H. performed all experiments and participated in the writing of the paper. R. V. and E. B. performed the ChIP assay. A. L. G. conceived the project, supervised all experiments, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard I. Morimoto for the HSP70 antibodies and Pfizer for the HSP90 inhibitor PF-4942847. We also thank Dr. Angela L. Tyner and Dr. Bradley J. Merrill for discussions and William F. Richter for technical support. The HSP70 expression plasmid was obtained from Dr. Lois Greene via Addgene.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 5R01CA138409 (to A. L. G.) and 5 T32 DK007788-14 (to M. H.) and a bridge funding grant from the University of Illinois at Chicago (to A. L. G.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- NRFM

- negative regulator of FOXM1

- HSP

- heat shock protein

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- 9AA

- 9-aminoacridine.

References

- 1.Laoukili J., Stahl M., and Medema R. H. (2007) FoxM1: at the crossroads of ageing and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1775, 92–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang P., Freedman M. L., Liu J. S., and Liu X. S. (2015) Inference of transcriptional regulation in cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7731–7736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halasi M., and Gartel A. L. (2013) FOX(M1) News: it is cancer. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 12, 245–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halasi M., and Gartel A. L. (2013) Targeting FOXM1 in cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85, 644–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radhakrishnan S. K., Bhat U. G., Hughes D. E., Wang I. C., Costa R. H., and Gartel A. L. (2006) Identification of a chemical inhibitor of the oncogenic transcription factor Forkhead Box M1. Cancer Res. 66, 9731–9735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat U. G., Zipfel P. A., Tyler D. S., and Gartel A. L. (2008) Novel anticancer compounds induce apoptosis in melanoma cells. Cell Cycle 7, 1851–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhat U. G., Halasi M., and Gartel A.L. (2009) FoxM1 is a general target for proteasome inhibitors. PLoS ONE 4, e6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gartel A. L. (2010) A new target for proteasome inhibitors: FoxM1. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 19, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halasi M., and Gartel A. L. (2009) A novel mode of FoxM1 regulation: positive auto-regulatory loop. Cell Cycle 8, 1966–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers M. V., and Workman P. (2007) Inhibitors of the heat shock response: biology and pharmacology. FEBS Lett. 581, 3758–3769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aghdassi A., Phillips P., Dudeja V., Dhaulakhandi D., Sharif R., Dawra R., Lerch M. M., and Saluja A. (2007) Heat shock protein 70 increases tumorigenicity and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 67, 616–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goloudina A. R., Demidov O. N., and Garrido C. (2012) Inhibition of HSP70: a challenging anti-cancer strategy. Cancer Lett. 325, 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer M. P. (2013) Hsp70 chaperone dynamics and molecular mechanism. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 38, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalinichenko V. V., Major M. L., Wang X., Petrovic V., Kuechle J., Yoder H. M., Dennewitz M. B., Shin B., Datta A., Raychaudhuri P., and Costa R. H. (2004) Foxm1b transcription factor is essential for development of hepatocellular carcinomas and is negatively regulated by the p19ARF tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 18, 830–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Major M. L., Lepe R., and Costa R. H. (2004) Forkhead box M1B transcriptional activity requires binding of Cdk-cyclin complexes for phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of p300/CBP coactivators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2649–2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fribley A., Zeng Q., and Wang C. Y. (2004) Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 induces apoptosis through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress-reactive oxygen species in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9695–9704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeil J. A., Zermati Y., Vandekerckhove J., Cathelin S., Kersual J., Dussiot M., Coulon S., Moura I. C., Zeuner A., Kirkegaard-Sørensen T., Varet B., Solary E., Garrido C., and Hermine O. (2007) Hsp70 regulates erythropoiesis by preventing caspase-3-mediated cleavage of GATA-1. Nature. 445, 102–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matokanovic M., Barisic K., Filipovic-Grcic J., and Maysinger D. (2013) Hsp70 silencing with siRNA in nanocarriers enhances cancer cell death induced by the inhibitor of Hsp90. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 50, 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohde M., Daugaard M., Jensen M. H., Helin K., Nylandsted J., and Jäättelä M. (2005) Members of the heat-shock protein 70 family promote cancer cell growth by distinct mechanisms. Genes Dev. 19, 570–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beshiri M. L., Islam A., DeWaal D. C., Richter W. F., Love J., Lopez-Bigas N., and Benevolenskaya E. V. (2010) Genome-wide analysis using ChIP to identify isoform-specific gene targets. J. Vis. Exp. 41, pii:2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossin L., Etienne S., Gaborit N., Pinzano A., Cournil-Henrionnet C., Gerard C., Payan E., Netter P., Terlain B., and Gillet P. (2004) Induction of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) by proteasome inhibitor MG 132 protects articular chondrocytes from cellular death in vitro and in vivo. Biorheology 41, 521–534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford L. J., Walker B., and Irvine A. E. (2011) Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 5, 101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halasi M., Wang M., Chavan T. S., Gaponenko V., Hay N., and Gartel A. L. (2013) ROS inhibitor N-acetyl-l-cysteine antagonizes the activity of proteasome inhibitors. Biochem. J. 454, 201–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neznanov N., Gorbachev A. V., Neznanova L., Komarov A. P., Gurova K. V., Gasparian A. V., Banerjee A. K., Almasan A., Fairchild R. L., and Gudkov A. V. (2009) Anti-malaria drug blocks proteotoxic stress response: anti-cancer implications. Cell Cycle 8, 3960–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandit B., and Gartel A. L. (2011) FoxM1 knockdown sensitizes human cancer cells to proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis but not to autophagy. Cell Cycle 10, 3269–3273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carr J. R., Park H. J., Wang Z., Kiefer M. M., and Raychaudhuri P. (2010) FoxM1 mediates resistance to Herceptin and paclitaxel. Cancer Res. 70, 5054–5063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok J. M., Peck B., Monteiro L. J., Schwenen H. D., Millour J., Coombes R. C., Myatt S. S., and Lam E. W. (2010) FOXM1 confers acquired cisplatin resistance in breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 24–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millour J., de Olano N., Horimoto Y., Monteiro L. J., Langer J. K., Aligue R., Hajji N., and Lam E. W. (2011) ATM and p53 regulate FOXM1 expression via E2F in breast cancer epirubicin treatment and resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 1046–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilarsky C., Wenzig M., Specht T., Saeger H. D., and Grützmann R. (2004) Identification and validation of commonly overexpressed genes in solid tumors by comparison of microarray data. Neoplasia 6, 744–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao B., Wang Z., Ali S., Kong D., Banerjee S., Ahmad A., Li Y., Azmi A. S., Miele L., and Sarkar F. H. (2011) Over-expression of FoxM1 leads to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell phenotype in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 112, 2296–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Raychaudhuri P., and Park H. J. (2011) FoxM1: A master regulator of tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 71, 4329–4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gartel A. L. (2011) Thiostrepton, proteasome inhibitors and FOXM1. Cell Cycle 10, 4341–4342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng X. H., Black M., Ustiyan V., Le T., Fulford L., Sridharan A., Medvedovic M., Kalinichenko V. V., Whitsett J. A., and Kalin T. V. (2014) SPDEF inhibits prostate carcinogenesis by disrupting a positive feedback loop in regulation of the Foxm1 oncogene. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gartel A. L. (2015) Targeting FOXM1 auto-regulation in cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16, 185–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myung J., Kim K. B., and Crews C. M. (2001) The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and proteasome inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 21, 245–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman M. Y., and Gabai V. L. (2015) Hsp70 in cancer: back to the future. Oncogene 34, 4153–4161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gartel A. L. (2009) p21(WAF1/CIP1) and cancer: a shifting paradigm? Biofactors 35, 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]