Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus possesses a multitude of mechanisms by which it can obtain iron during growth under iron starvation conditions. It expresses an effective heme acquisition system (the iron-regulated surface determinant system), it produces two carboxylate-type siderophores staphyloferrin A and staphyloferrin B (SB), and it expresses transporters for many other siderophores that it does not synthesize. The ferric uptake regulator protein regulates expression of genes encoding all of these systems. Mechanisms of fine-tuning expression of iron-regulated genes, beyond simple iron regulation via ferric uptake regulator, have not been uncovered in this organism. Here, we identify the ninth gene of the sbn operon, sbnI, as encoding a ParB/Spo0J-like protein that is required for expression of genes in the sbn operon from sbnD onward. Expression of sbnD–I is drastically decreased in an sbnI mutant, and the mutant does not synthesize detectable SB during early phases of growth. Thus, SB-mediated iron acquisition is impaired in an sbnI mutant strain. We show that the protein forms dimers and tetramers in solution and binds to DNA within the sbnC coding region. Moreover, we show that SbnI binds heme and that heme-bound SbnI does not bind DNA. Finally, we show that providing exogenous heme to S. aureus growing in an iron-free medium results in delayed synthesis of SB. This is the first study in S. aureus that identifies a DNA-binding regulatory protein that senses heme to control gene expression for siderophore synthesis.

Keywords: bacterial transcription, biosynthesis, iron metabolism, siderophore, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a formidable human pathogen capable of causing a wide range of opportunistic infections, including endocarditis, meningitis, and osteomyelitis, and it is currently the most frequent cause of bloodstream infections in Canada and the United States (1–5). Like the vast majority of all characterized organisms, with the exception of some lactobacilli and spirochetes (6, 7), S. aureus requires the use of iron to survive. Iron in a human host, however, is typically not free as it is bound within host proteins that serve essential host functions, and at the same time, it limits the amount of readily available iron to invading microbes (8, 9). This process of iron limitation is referred to as host nutritional immunity and is an obstacle to the survival of microbes, including S. aureus.

To overcome this obstacle, S. aureus has evolved multiple sophisticated iron uptake mechanisms (10, 11). Because the predominant source of iron in the human body is iron bound to heme, representing greater than 70% of all intracellular iron, heme is an important source of iron during S. aureus infection (12). S. aureus acquires heme from hemoglobin using proteins of the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) pathway (13). This well characterized pathway involves a series of cell wall-anchored proteins, lipoproteins, membrane permeases, and cytosolic proteins. Together, these proteins function to bind hemoglobin, extract heme from hemoglobin, mobilize heme through the thick peptidoglycan layer to a membrane ABC transporter, and degrade heme once it enters the cytoplasm (10, 11, 14–16).

Representing less that 0.1% of iron in the body, an important extracellular source of iron is that which is bound by host glycoproteins transferrin and lactoferrin (9). Through the use of small iron-chelating molecules, referred to as siderophores, S. aureus is capable of removing iron from these glycoproteins and delivering it to the bacterial cell (10, 11). There are two predominant classes of siderophore synthesis pathways as follows: non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-dependent and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-independent siderophore (NIS)3 syntheses (17). Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase siderophore synthesis has been well characterized for many siderophores, such as enterobactin (18). S. aureus produces two citrate-based siderophores: staphyloferrin A (SA) and staphyloferrin B (SB). As NIS siderophores, SA and SB are synthesized not in a stepwise fashion using large multidomain/modular proteins but instead are constructed through use of synthetase enzymes that form siderophores by sequential condensation reactions of alternating subunits of dicarboxylic acid with amino-alcohols, alcohols, and diamines (19–22).

The biosynthetic enzymes and efflux protein for SA are encoded from within the sfa (also known as sfna) locus (22, 23), where genes sfaA, sfaB, and sfaC form an operon, and sfaD is divergently transcribed to sfaA. SfaB and SfaD are NIS type A-like synthetases that facilitate the condensation of d-ornithine with two molecules of citrate (22). SfaC is a pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent amino acid racemase, and SfaA is an efflux pump that secretes SA into the extracellular milieu (22, 24).

The 9-gene sbn gene cluster encodes for SB biosynthesis and efflux, and these genes have been implicated in virulence in both the mouse bacteremic and the rat infective endocarditis models of S. aureus infection (25, 26). SbnA and SbnB perform the first step in SB synthesis with the formation of the precursor molecules l-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (l-Dap) and α-ketoglutarate from O-phospho-l-serine and l-glutamate (21). SbnG acts as a citrate synthase to convert acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate into citrate (27, 28). l-Dap, citrate, and α-ketoglutarate are the constituents of SB. The siderophore synthetase enzymes SbnC, SbnE, and SbnF facilitate condensation reactions with these precursors to build the SB molecule, whereas SbnH is a decarboxylase that converts one of the two l-Dap molecules within SB into ethylenediamine (19). The function of the terminal gene product in the sbn operon, SbnI, is previously uncharacterized, and thus the foundation of this study was to determine the function of SbnI in the cell.

The regulation of genes that encode for proteins implicated in iron metabolism in S. aureus is controlled by the ferric uptake regulator (Fur), a transcriptional regulator found in many Gram-positive and -negative bacteria (29). Functioning as a dimer and with the use of metal cofactors, Fur binds to an AT-rich 19-bp palindromic consensus sequence referred to as the Fur box, located in the promoter region of regulated genes. Fur bound to the Fur box results in limited transcription of downstream genes (29, 30).

In the absence of Fur repression during growth in iron-starved conditions, some bacteria adopt additional regulatory mechanisms for fine-tuning gene expression of iron-regulated genes. In Ralstonia solanacearum, a soil-borne pathogen that also utilizes staphyloferrin B for iron acquisition, the synthesis of SB is negatively regulated by Fur in high iron concentrations and is also negatively regulated in low iron concentrations by PhcA (31). PhcA is an environmentally responsive transcription factor that responds to the presence of the autoinducer 3-hydroxypalmitic acid methyl ester, a molecule produced as a result of quorum sensing (31, 32). Thus PhcA is able to afford R. solanacearum as an additional level of control for siderophore synthesis that works in response to environmental cues. In S. aureus, however, it is unclear as to what regulates the expression of many genes implicated in iron metabolism when cells are growing in limited iron supply.

In this study, we report a novel heme-responsive regulatory protein, SbnI, that controls expression of the genes in the sbn operon and thus controls siderophore-mediated iron uptake. The sbnI mutant had an SB-dependent growth defect in iron-limited media, because of delayed and reduced production of SB, due to significantly decreased transcript levels for genes sbnDEFGH in the mutant. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrated that SbnI binds DNA upstream of a newly identified promoter within the sbnC coding region. Moreover, we show that SbnI is capable of binding to heme and heme binding inhibits DNA binding. We propose a model whereby SbnI is required for transcription throughout the SB biosynthetic operon and senses intracellular heme as a means to reduce SB synthesis in favor of heme acquisition. This model supports the observations of Skaar et al. (12) who reported that heme is the preferred iron source for S. aureus.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Media

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed and described in Table 1. Strains were stored in 15% glycerol stocks at −80 °C and, prior to use, were streaked onto tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Difco) agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic. Solid media were prepared with addition of 1.5% w/v Bacto agar (Difco). Concentrations of antibiotics used were as follows: 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 100 μg/ml ampicillin for Escherichia coli selection, 4 μg/ml tetracycline, 5 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 3 μg/ml erythromycin for S. aureus selection. E. coli strains were grown in Luria Broth (Difco), and S. aureus strains were grown in TSB or either Chelex-100-treated Tris minimal succinate (cTMS) or Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) (Gibco) medium for growth under iron restrictions. All solutions and media were made using water purified with the Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

The following abbreviations are used: ApR, ampicillin resistance; CmR, chloramphenicol resistance; EryR, erythromycin resistance; KmR, kanamycin resistance; TetR, tetracycline resistance; AUAP, abridged universal anchor primer; UAP, universal anchor primer.

| Bacterial strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides | Description | Source or Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F-Ф80 dLacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 nupG gyrA96 glnV44 thi-1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) λ−supE44 relA1 deoR Δ (lacZYA-argF)U169 | Promega |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB (rB− mB+)λ (DE3 [lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 sam7 nin5]) | Novagen |

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | rk−mk+ accepts foreign DNA | 47 |

| RN6390 | Prophage-cured wild-type strain | 48 |

| H306 | RN6390 sirA::Km; KmR | 25 |

| H984 | RN6390 sbnI::Tet; TetR | This study |

| H1312 | H984/pSbnI; sbnI mutant complemented with sbnI | This study |

| H1313 | H187 containing pCN51 | This study |

| H1317 | H984 containing pCN51 | This study |

| H1324 | RN6390 sbn; TetR | 23 |

| H1448 | RN6390 hts::Tet; TetR | 23 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28a(+) | Overexpression vector for His6-tagged proteins; KmR | Novagen |

| pCN51 | Cadmium-inducible expression vector; EryR | 49 |

| psbnI (pAB1) | pCN51-sbnI; pCN51 vector for expression of sbnI; EryR | This study |

| pGylux | Promoterless E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector for luminescence, ApR, CmR | 33 |

| pCM326 | 1479-bp sbnA/B cloned into pGylux; ApR, CmR (fragment A) | This study |

| pCM328 | 2322-bp sbnA/B/C cloned into pGylux; ApR, CmR (fragment B) | This study |

| pCM330 | 2389-bp sbnC/D cloned into pGylux; ApR, CmR (fragment C) | This study |

| pCM332 | 2395-bp sbnD/E cloned into pGylux; ApR, CmR (fragment D) | This study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Cloning of sbnI from S. aureus for pET28a(+) | GC AGC CAT ATG AAT CAT ATT GCT GAA CAT TTA A (forward) | |

| TTG TGT CTC GAG TCA TCA TAT TTC CCT CAA CAT (reverse) | ||

| Cloning of sbnI from S. aureus for complementing vector (psbnI) | TTG AGC GGA TCC CTT AAG CCA TCC ACA TCC TG (forward) | |

| TTG CGC GAA TTC TCG CTA TCA ATA CCG TAA ATC (reverse) | ||

| Cloning of fragment A | GCC TCC CGGGTCAATAAAATATTTATGATTTACATGC (forward) | |

| GACTCCCGGGAACTTGCTTCCATAACTGCAATT (reverse) | ||

| Cloning of fragment B | GACTCCCGGGTAATTTAGGCATTGCGTTG (forward) | |

| GACTCCCGGGCTGCAACCATTAAAGG (reverse) | ||

| Cloning of fragment C | GACTCCCGGGTGTCTGAACATTGCAG (forward) | |

| GACTCCCGGGAAATGAACGGCGAATAC (reverse) | ||

| Cloning of fragment D | GACTCCCGGGACTGACAGTACTTGT (forward) | |

| GACTCCCGGGCCTGTGTTACTAAAC (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnA | ACTTCTGGTAATTTAGGCATTGCG (forward) | |

| TGCATCAGGTTCTTCAACCATTTC (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnB | CCTGAAAATGGACACATCGC (forward) | |

| CAAAATAATGACGCCACTTGC (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnC | ATGAATGGGAAGTGGCTCG (forward) | |

| GCTAATGGATGAAATGGACGAT (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnD | CGTAGAAATACAGTTGTGGAGTGG (forward) | |

| AAATAAGCATACCGCCAAACC (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnE | CGAATCCATTAGGGCAAACAG (forward) | |

| CTTAACATCGGTGAATCAGGC (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnF | TTTTATGCGATGGAAGGG (forward) | |

| CGTCGTTTCTACTTTATCTTTGTCG (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnG | TCATTAAAGTGTTGGATATGGGTGC (forward) | |

| TTAGCCATCTCCATTGCATCAAG (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: sbnH | CGCTCGCAATGCCAAAGATTC (forward) | |

| TAACGCCTATGCCACCACCAAG (reverse) | ||

| RT-PCR: rpoB | AGAGAAAGACGGCACTGAAAACAC (forward) | |

| ATAACGACCCACGCTTGCTAAG (reverse) | ||

| GSP1 | GAAAGCTGATGTGCTGTTAG | |

| GSP2 | GAGCCCGGGTCTAGACGCATACTTGAAGACGACAG | |

| AUAP | GATACCCGGGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC | |

| UAP | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACGGGIIGGGIIGGGIIG | |

Bacterial Growth Curves

Bacteria were cultured on TSB agar, and then several single isolated colonies were picked and inoculated into 2 ml of cTMS (flask/volume ratio of 10:1) and grown for ∼8 h at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. The bacteria were then harvested, resuspended in fresh cTMS medium, and inoculated into 5 ml of cTMS medium (flask/volume ratio 10:1) to a starting A600 equivalent of 0.005.

Western Blotting

Rabbit polyclonal antisera recognized SbnI were generated by ProSci (Poway, CA) using the custom antibody production package number 1.

Cells were grown to an A600 of 1.0, and 3 × 109 colony-forming units were harvested and resuspended in 0.1 ml of lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm glucose, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 5 μg of lysostaphin, 1× Laemmli buffer (60 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromphenol blue)) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then boiled for 10 min before being run through a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane following standard protocols. Primary anti-SbnI polyclonal antiserum was used at a dilution of 1:1000, and secondary antiserum (anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to IRDye 800; Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used at a 1:20,000 dilution. Membranes were scanned on a Li-Cor Odyssey Infrared Imager (Li-Cor Biosciences) and visualized using Odyssey Version 3.0 software.

RNA Isolation and qPCR

S. aureus RN6390 and H984 (RN6390 sbnI) were grown in quadruplicate cultures in 2 ml of cTMS medium for 8 h. Cultures were then harvested and subcultured at A600 0.005 in 10 ml of cTMS and grown to mid-exponential phase (A600 ∼1.0). Cells equating to an A600 of 3.0 were harvested for each culture, and RNA extraction was performed by E.Z.N.A® total RNA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions with the addition of 0.25 μg/ml lysostaphin to the lysis solution. RNA purity was determined by agarose gel, and RNA concentration was determined by NanoDrop® ND-1000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. cDNA preparation was performed using 500 ng of total cellular RNA reverse-transcribed using SuperscriptTM II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For each qPCR, 1 μg of cDNA was amplified in a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Life Science) using the iScript One-Step RT-PCR kit with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad). Gene expression for each sample was quantified in relation to rpoB expression. A standard curve was generated for each gene examined.

Disc Diffusion Assays

Concentrated spent culture supernatants were prepared from 10-ml cultures of S. aureus RN6390. Culture supernatants were taken at 10, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 36 h after inoculation. Growth was assessed via A600, and culture densities between replicates and strains were normalized for each time point. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the supernatant was lyophilized for 12 h. Lyophilized supernatant was resuspended in 0.5 ml of sterile double-distilled H2O. S. aureus cells, the htsA mutant strain or the sirA mutant strain, were seeded into TMS agar containing 10 μm EDDHA to achieve 1 × 104 cells per ml. For each replicate, 10 μl of concentrated supernatant were applied to sterile paper discs that were then placed onto the plates containing the seeded reporter strains, and growth about the disc was measured after 24 and 48 h of incubation at 37 °C.

Identification of Promoters

Four DNA fragments, spanning the sbn operon from sbnA to sbnE, were cloned into the promoterless shuttle vector pGylux (33) as follows: fragment A of 1479 bp (pCM326); fragment B of 2322 bp (pCM328); fragment C of 2389 bp (pCM330); and fragment D (pCM332) of 2395 bp. To measure luciferase activity, individual colonies from S. aureus carrying these plasmids were inoculated into TMS medium and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Cells were subsequently inoculated into cTMS with or without 1 μm FeCl3 at an A600 0.1 and incubated for 8 h. At that time, the A600 and luminescence were measured on a SynergyH4 Hybrid Reader (Biotek). Luminescence values were expressed as cps/A600.

Identification of a Transcription Start Site

To identify an initiation of transcription, we used rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). The original mRNA was prepared from S. aureus RN6360 grown in cTMS, as per the protocol described for qPCR. First strand cDNA was synthesized by incubating for 50 min at 42 °C the following: 1 μg of RNA, 1 μm gene-specific primer 1 (GSP1), 50 μm dNTP, and 20 units of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The mRNA was removed by treating the synthesized cDNA with RNase mix (0.5 units of RNaseH and 50 units of RNaseT1) for 30 min at 37 °C. After purification of the cDNA with the BioArray cDNA purification kit (ENZO Life Sciences), it was C-tailed with 20 units of terminal transferase (Roche Diagnostics) and 0.5 mm dCTP as recommended by the supplier. The first PCR was performed using the universal anchor primer (Invitrogen) that will anneal to the C-tailed cDNA and an sbnC-specific primer GSP2. The second PCR (177 bp) was performed using the first PCR as a template, a primer that will anneal to the abridged universal anchor primer (Invitrogen) and the same specific primer GSP2. GSP2 and abridged universal anchor primer contain SmaI restriction endonuclease sites that were later used for cloning the second PCR product into pGEM7. The pGEM7 clones were later sequenced to determine the initiation of transcription.

Protein Expression and Purification

Recombinant SbnI protein was overexpressed and purified essentially as described previously (34). In brief, cells were grown to mid-log phase at 37 °C with aeration before the addition of 0.4 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; the cells were then grown for an additional 16 h at room temperature with shaking before harvesting. Cells were resuspended in 50 mm Hepes, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.4, prior to lysis at 25,000 p.s.i. in a Cell-Disruptor (Constants Systems Ltd.). Cell debris was pelleted by 15 min of centrifugation at 3000 rpm in a Beckman Coulter Allegra® 6R benchtop centrifuge that was followed by ultracentrifugation at 50,000 rpm in a Beckman Coulter Optima® L-900K ultracentrifuge for 45 min. The lysate was filtered with a 0.45-μm nylon filter (VWR) and then applied to a 1-ml HisTrap column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A (50 mm Hepes, 1 mm DTT, and 10 mm imidazole, pH 7.4). The His6-SbnI was eluted with a 0–80% concentration of buffer B (50 mm Hepes, 1 mm DTT, and 500 mm imidazole, pH 7.4). Protein was dialyzed in 50 mm Hepes, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.4, at 4 °C. Protein purification was determined by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined through the Bradford assay using the Bio-Rad protein assay dye (Bradford) reagent concentrate (5×), and samples were read at A595; a standard curve was made for each concentration determination with 1 mg/ml BSA.

Oligomerization Analysis

Size exclusion chromatography was performed using a Superdex 200 10/30 GL column (Amersham Biosciences) coupled to an FPLC system (Pharmacia). The column was equilibrated with 300 mm ammonium formate buffer, pH 7.4. SbnI samples, in 300 mm ammonium formate, were run in a 500-μl volume injected into the column and eluted at a flow rate of 200 μl/min. Protein was followed by absorption measurements at 280 nm. The column was calibrated with blue dextran (void volume), β-amylase from sweet potato (200 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase from yeast (150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), carbonic anhydrase from bovine erythrocytes (29 kDa), and cytochrome c from horse heart (12.4 kDa).

Recombinant SbnI was dialyzed in 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4, and 100 mm NaCl prior to sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation analysis. For analysis of SbnI in reducing agent, buffer also contained 10 mm DTT added post-dialysis. The dialysis buffer was retained for use in the reference sector for all runs. Analytical ultracentrifugation was carried out in a Beckman XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge with a four-hole An-60Ti rotor and double-sector cells with Epon charcoal centerpieces. Centrifugation was carried out at 5 °C. A total of 60 absorbance measurements were taken at 280 nm at 5-min intervals at 0.002-cm radial steps and averaged over three readings. The rotor speeds were 35,000 rpm for SbnI in 100 mm NaCl and 45,000 rpm for SbnI in 20 mm DTT. Data were analyzed using non-linear regression in Sedfit software and fit to a c(s) distribution to determine sedimentation coefficients corrected to 20 °C and in H2O. All data were fit to a root mean square deviation equal to or less than 0.007.

DNA Binding Assays

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed with purified SbnI and double-stranded, fluorescently labeled DNA. The DNA probe was amplified through PCR with IRDye® 700-labeled custom primers purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT®). Protein and DNA were incubated in a 25-μl volume that contained 120 ng of fluorescently labeled DNA, 50 mm Hepes, 240 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 15.2 μg/ml poly[d(I-C)], and SbnI, at room temperature for 45 min. Samples were separated on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels in TBE buffer (10 mm Tris, 89 mm Tris borate, 2 mm EDTA, pH 8.3) at 120 V for 1.5 h. Competition EMSAs used 120 ng of labeled sbnC probe and 1200 ng of either unlabeled sbnC or rpoB probe. For EMSAs containing heme, a 4 mm heme stock was diluted to 250 μm in 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, just prior to use. For preparation of heme stock, see below.

Heme Titrations

Heme stocks were prepared as follows. Bovine heme (Sigma) was resuspended to 5 mm in 0.1 nN NaOH (i.e. 0.00326 g/ml) and vortexed vigorously until in solution. The solution was sterilized by filtration through a 0.2-micron filter. A series of dilutions were prepared in 0.1 n NaOH, and scanning UV-Vis spectra were taken on the solution. The post-filtration concentration was determined on this solution using the molar extinction coefficient for hemin in 0.1 n NaOH of 58,400 cm−1 m−1 at 385 nm (35). Heme solution was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. Heme stocks were diluted just prior to use in the buffer or media appropriate to the experiment.

Heme titrations, using UV-Vis spectroscopy, were performed using 1 μm SbnI and increasing concentrations of heme. SbnI was in 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature with heme concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 2 μm, with a 0.2 μm increase after each reading. Heme stocks (2.5 mm) were prepared from hemin chloride (Sigma) by adding NaOH, which were further diluted with 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4, to a working concentration of 200 μm. UV-Vis spectra were recorded using Cary 50 Bio UV-Vis spectrophotometer with background correction for buffer and for each heme concentration. Triplicate samples were recorded.

ESI-MS was performed by using 50 μm recombinant SbnI, stored in 300 mm ammonium formate and 10 mm DTT, pH 7.4, and titrated with molar equivalents of heme. Heme was prepared in a 1 mm stock by dissolving 10 mg of hemin in concentrated NH4OH neutralized with 10 mm ammonium formate, pH 6. The average incubation time for SbnI and heme was 3 min. Spectral data were recorded with Bruker Micro-TOF II (Bruker Daltonics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) operated in the positive ion mode set for soft ionization. Scan parameters were set for 500–4000 m/z, and the spectra were collected for 1 min, minimum, and deconvoluted using the maximum entropy license for the Bruker Compass data analysis software.

Results

Requirement of Iron-regulated SbnI for SB Production in S. aureus

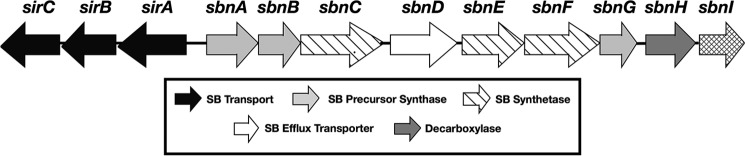

SB can be synthesized entirely in vitro using purified sbn-derived enzymes (19–21, 27). Indeed, SB can be synthesized from the activities of SbnA, SbnB, SbnC, SbnE, SbnF, SbnG, and SbnH when provided with O-phospho-l-serine, glutamate, oxaloacetate, and acetyl-CoA as substrates (19–21, 27). Despite its product seemingly having no essential enzymatic role in SB synthesis, sbnI, the ninth gene in the sbn operon (Fig. 1), is conserved in S. aureus strains, along with the rest of the sbn operon. This suggests it may play an important role in SB biosynthesis. Searches of the protein databases revealed that the protein shared limited sequence similarity with the DNA partitioning proteins ParB and Spo0J.

FIGURE 1.

sir-sbn locus schematic. The sbnI gene is situated as the 9th and terminal gene of the operon.

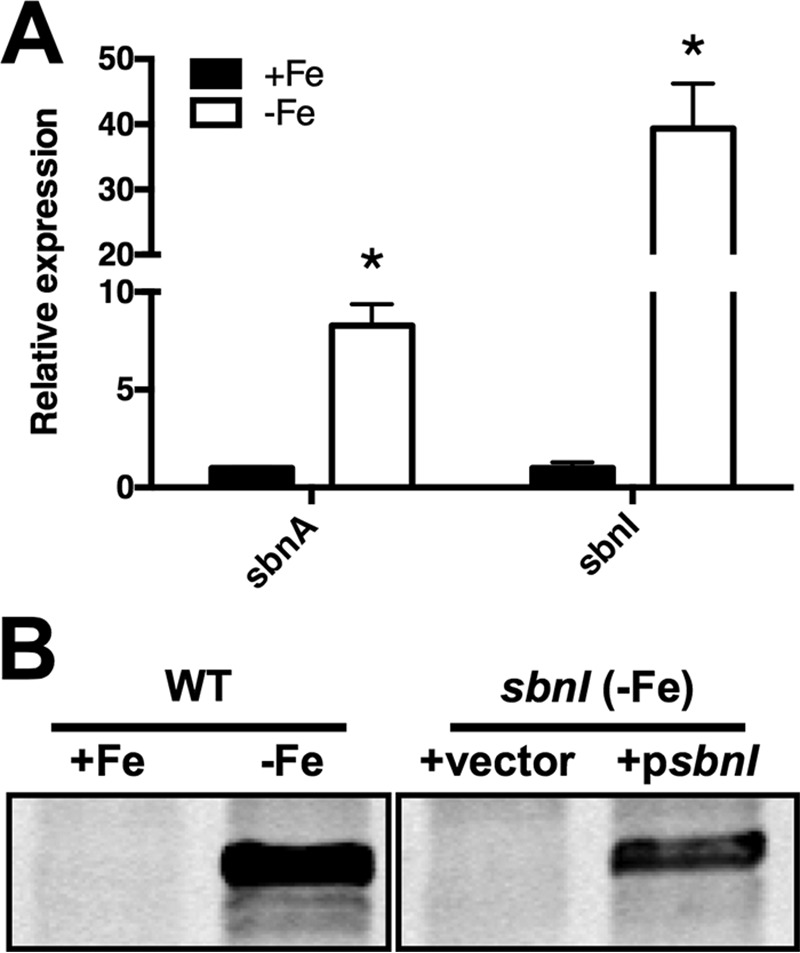

To assess the functional role, if any, of SbnI in SB synthesis, we knocked out sbnI by insertion of a tetracycline-resistance cassette into the middle of the gene. As part of our initial studies into the functional role of SbnI, we first confirmed its expression profile in WT S. aureus. A canonical Fur box was situated upstream of sbnA, and as such, expression of the genes within the operon is regulated by iron levels. qPCR was used to confirm that expression of the predicted terminal gene of the operon, sbnI, is similarly regulated by iron levels (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis, using anti-SbnI antisera, corroborated the qPCR findings, demonstrating that SbnI protein expression was controlled by iron (Fig. 2B). Western blots also confirmed that the sbnI insertion mutant (H984) lacked detectable expression of SbnI (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Expression of sbnI is regulated by iron. A, qPCR data showing significant increase in gene expression of sbnA and sbnI in WT RN6390 when grown in iron-restricted media versus iron-replete medium (*, p < 0.01). All strains were grown in cTMS with (+Fe, solid bars) or without (−Fe, clear bars) 50 μm FeCl3. Gene expression of strains grown in iron-replete medium is used as comparator and is arbitrarily set to 1. Statistics were performed using Student's unpaired t test. B, Western blot with α-SbnI antisera demonstrating iron-regulated control of SbnI. WT RN6390 cells were grown in cTMS medium with (+Fe) or without (−Fe) addition of 50 μm FeCl3 (left panel). Immunoblotting also confirmed the lack of expression of SbnI in the sbnI mutant strain carrying pCN51 (vehicle control; vector), and complementation of expression in the mutant carrying psbnI (carries sbnI gene).

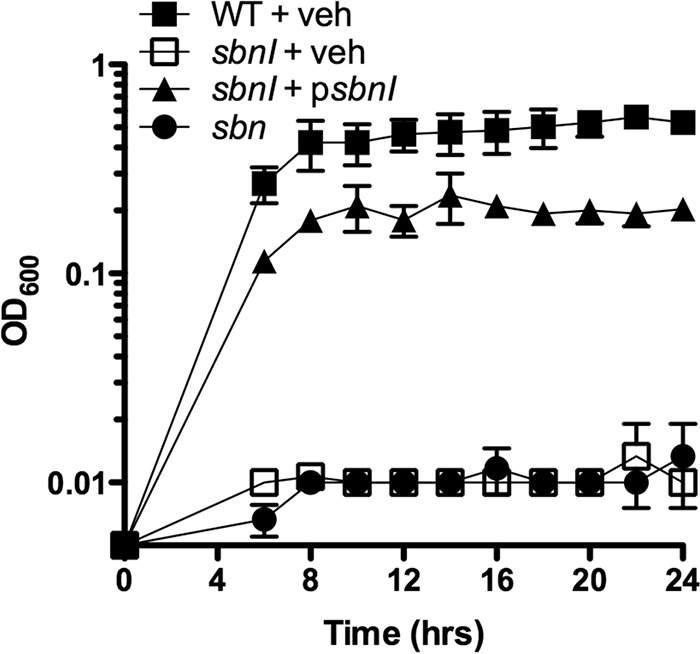

With the confirmed sbnI::Tet mutant strain, H984, growth kinetics were recorded, comparing the relative growth of the WT, H984, H984 + psbnI, and the Δsbn (i.e. complete operon knock-out) strains grown in RPMI 1640 medium, an iron-restricted, chemically defined medium. In this medium, and in comparison with the WT and complemented strains, H984 had a severe growth defect, similar to the growth defect observed for strain H1342, the Δsbn strain (Fig. 3). Because our previous work has shown that production of SA is repressed in RPMI 1640 medium (28), these results suggested that SbnI was critical for SB-mediated iron acquisition.

FIGURE 3.

Growth kinetics of S. aureus strains in RMPI 1640 medium. RN6390 and derivatives were grown in RMPI 1640 medium incorporating 0.2 μm EDDHA to further enhance iron restriction. Vehicle control (veh) was empty pCN51.

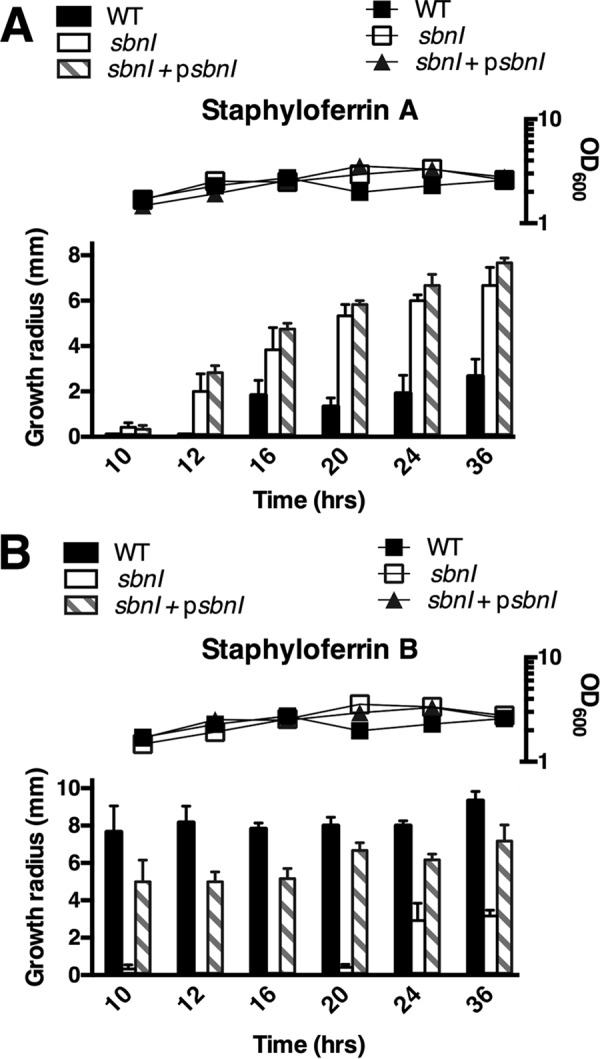

Because WT S. aureus strains have the ability to produce both SA and SB under conditions of iron starvation, and because their activity can be readily detected in bioassay experiments (20, 21, 27, 28), a disc diffusion bioassay was performed to examine SB production in RN6390 (WT), H984, and the complemented strain (H984 + psbnI). For these experiments, bacteria were grown in cTMS medium which, as opposed to RPMI 1640 medium, does not result in inhibition of SA or SB. As shown in Fig. 4, in this medium the growth was comparable among the three strains tested, throughout the duration of the experiment. Spent culture supernatants were taken at six designated time points, hours 10, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 36 post-inoculation. The supernatants were then applied onto sterile paper discs on agar seeded with the sirA or htsA mutant strains. The sirA strain is unable to uptake SB and thus relies on SA uptake for growth, whereas the htsA strain is unable to uptake SA, and thus its growth is reliant on SB. The data demonstrated that, compared with WT RN6390, H984 seemed to make detectable quantities of SA sooner in the growth cycle (Fig. 4A). However, more striking, and in agreement with data in Fig. 3, although RN6390 produced detectable quantities of SB by 10 h, we were unable to detect SB from the supernatants of H984 until at least the 24-h time point. This defect was complemented by supplying sbnI in trans (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that SbnI plays a critical role in the synthesis of SB, particularly at early time points, and that the absence of SbnI does not hinder SA production, but rather it may result in increased production of SA.

FIGURE 4.

Disc diffusion assay demonstrating requirement of sbnI for SB production. RN6390 and derivatives were grown in cTMS medium with 0.1 μm EDDHA. Triplicate spent culture supernatants were analyzed at indicated time points post-inoculation. Supernatants were concentrated and resuspended in sterile distilled H2O and placed onto sterile paper discs subsequently placed on cTMS agar seeded with either the sirA (A) or the htsA (B) strain. Growth around the disc was an indication of the presence of SA (A) or SB (B). All strains were grown in cTMS medium in which growth, as measured by OD600 (right y axis), was found to be comparable.

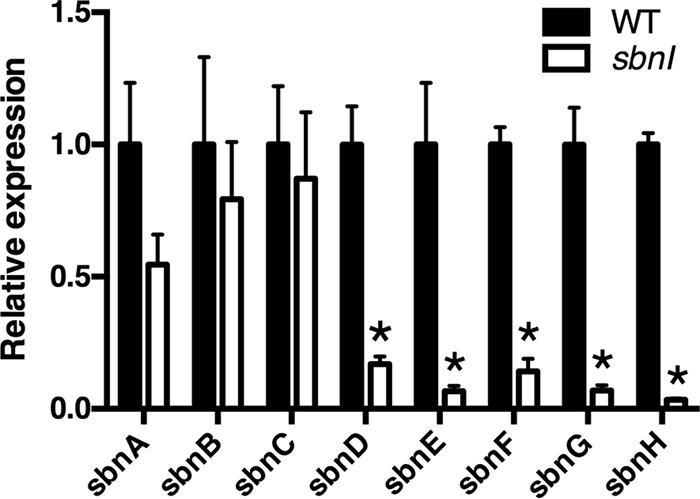

Expression of the SB Biosynthetic and Efflux Genes Requires SbnI

In accordance with the idea that SbnI affected synthesis of SB, despite having no clear enzymatic function in the biosynthetic pathway (20, 21, 27), and given that SbnI shares low sequence similarity to the DNA-binding proteins ParB and Spo0J, we theorized that SbnI may function as a regulatory protein that impacted expression of SB biosynthetic genes. To evaluate this, RNA levels were measured for each of the genes throughout the sbn operon, comparing levels in WT to those in H984. Strikingly, these experiments revealed a dramatic drop (90–99% decrease) in RNA transcripts for genes sbnD through sbnH in H984 compared with RN6390 (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Mutation of sbnI results in altered expression throughout the sbn operon. RN6390 and its sbnI::Tet derivative were grown in cTMS with 0.1 μm EDDHA, a medium in which growth was comparable between the two strains. qPCR was used to measure RNA levels for each gene, where WT gene expression was set to 1. Statistics were performed using the Students unpaired t test. *, p < 0.005.

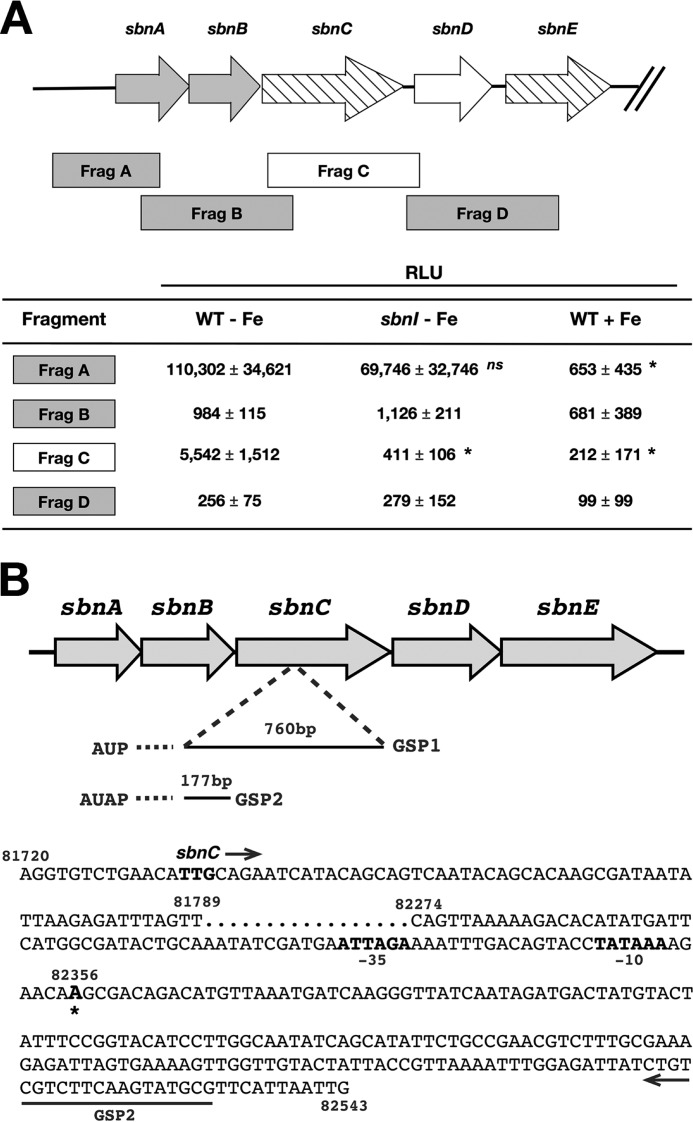

Identification of an Internal Promoter in the sbn Operon

Because SbnI had a drastic effect on the expression of genes downstream of sbnC, we theorized that SbnI may be regulating expression of genes downstream of sbnC by regulating the activity of a promoter internal to the operon. In an attempt to demonstrate this, we cloned several DNA fragments spanning the region from sbnA through sbnE upstream of the promoterless luciferase genes in the vector pGylux (Fig. 6A). The constructs were then introduced into strains RN6390 and H984, and the bacteria were grown in cTMS medium with or without added iron. As expected, these experiments showed that there was robust promoter activity in the fragment carrying the promoter region upstream of sbnA, and this activity was ∼40% decreased in H984 (Fig. 6A), in agreement with the qPCR data in Fig. 5. Furthermore, in agreement with the presence of a canonical Fur box upstream of sbnA, the activity from the sbnA promoter was significantly (p < 0.01) attenuated when the cells were grown in medium containing iron versus in the same medium but lacking iron (Fig. 6A). In addition to DNA fragment A, carrying the sbnA promoter region, we observed that DNA fragment C also demonstrated fairly strong promoter activity that was also significantly (p < 0.01) regulated by iron levels in the growth medium. Moreover, this activity was abrogated in H984, indicating that it was SbnI-dependent. This phenotype was complemented in H984 carrying sbnI in trans (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Identification of a promoter within the sbnC coding region. A, DNA fragments, spanning genes sbnA–E, were cloned into the pGylux vector, and luciferase activity was measured. Activity was expressed at cps/A600. Statistical analyses were performed for each respective fragment, comparing the luciferase activity of either the sbnI strain without iron (sbnI − Fe) to WT without iron (WT − Fe) or WT with iron (WT + Fe) to WT without iron (WT − Fe). Statistics were performed using Student's unpaired t test; *, p < 0.01, ns = not significant. B, identification of initiation of transcription. Using the 5′RACE method, A81175 (based on S. aureus Newman genome sequence) was identified as the +1 site and is located 625-bp downstream of the sbnC start codon. Two PCR products of ∼760 bp (AUP/GSP1) and 117 bp (abridged universal anchor primer/GSP2) were generated, and the 117-bp product was cloned into pGEM7 and sequenced. The locations of the primer GSP2 and the −10 and −35 sites are indicated.

RACE was performed for fragment C to elucidate the transcription start site present within the fragment. The experiment was repeated on multiple biological samples for robustness and demonstrated the presence of a confirmed transcription start site at position A82356 (based on genome S. aureus Newman), which is located 625 bp downstream of the start of the sbnC coding region (Fig. 6B).

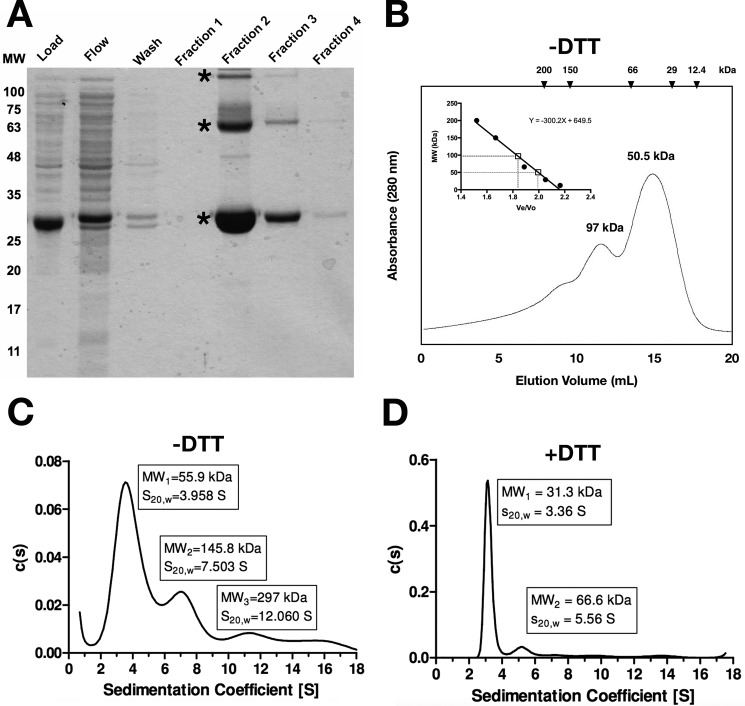

SbnI Forms Dimers and Is Able to Bind DNA Region Upstream of sbnD

Based on data demonstrating the SbnI-dependent regulation of an internal promoter within the sbn operon, we next were interested in investigating whether SbnI controlled gene expression through direct binding to nucleic acids. However, because DNA-binding proteins frequently form dimers or oligomers, we investigated this property. His6-tagged SbnI was purified by metal affinity chromatography (Fig. 7A) and used to evaluate the oligomerization status of the protein in solution. Size exclusion chromatography and sedimentation velocity-analytical ultracentrifugation determined that SbnI forms dimers and tetramers in non-reducing conditions but primarily monomers with limited dimer conformation under reducing conditions (i.e. in the presence of 10 mm DTT) (Fig. 7, B–D).

FIGURE 7.

SbnI forms dimers and tetramers in solution. A, purification of recombinant His6-SbnI. Various samples during the purification process are run through a polyacrylamide gel, starting with pre-column (load), flow-through (flow), wash fraction (wash), and elution fractions 1–4. The identity of the three bands labeled with an asterisk was confirmed as SbnI using MALDI. B, size exclusion chromatography of SbnI. Chromatogram represents size exclusion data of SbnI run in 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4, at flow rate of 0.2 ml/min across Superdex 200 FPLC column. Elution volumes of known protein standards are shown at the top and are used to generate a standard curve (inset). C and D, sedimentation velocity-analytical ultracentrifugation was performed on SbnI run in 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl. C, 10 mm DTT was included.

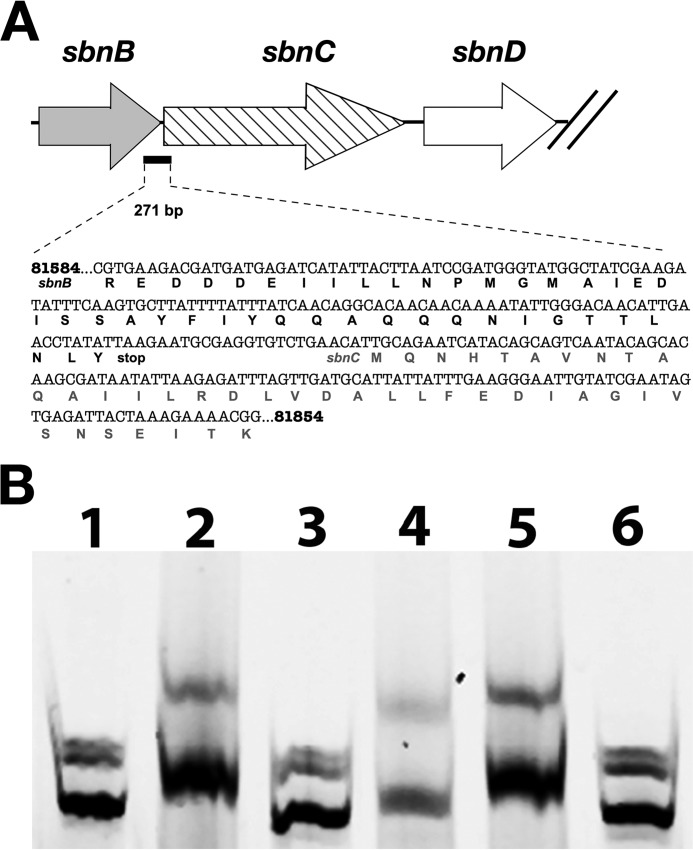

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed with purified His6-SbnI, in non-reducing conditions so as to promote oligomerization of the protein. Based on the luciferase assay and RACE data suggesting an internal promoter in the sbnC region, we sought to find a DNA fragment upstream of sbnD that could be bound by SbnI. Multiple EMSAs were performed using 250–300-bp fragments located within and upstream of the region identified as fragment C in Fig. 6. A 271-bp probe located 772 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site internal to the sbnC coding region was identified as a binding site for SbnI (Fig. 8). The inability of denatured protein (SbnI incubated for 10 min at 100 °C) and His6-SbnG to bind this DNA fragment (Fig. 8, lanes 3 and 6, respectively) confirmed binding specificity of SbnI for this fragment, ruling out the possibility of nonspecific interactions with the IRDye-700 molecule. Binding specificity to this probe was confirmed by showing that excess unlabeled sbnC DNA fragment, but not excess nonspecific (i.e. rpoB) unlabeled DNA, could interfere with the binding of SbnI to the labeled fragment.

FIGURE 8.

Identification of a DNA-binding site for SbnI. A, schematic identifying the location of a 271-bp DNA fragment that was used for the EMSA experiment illustrated in B. The base numbering is from genome sequence for S. aureus strain Newman. B, electrophoretic mobility shift assay demonstrating SbnI binding to DNA fragment shown in A. Each sample contained 120 ng of fluorescently labeled, 270-bp dsDNA, as well as the following: lane 1, DNA alone; lane 2, 25 μm SbnI; lane 3, 25 μm denatured SbnI; lane 4, 25 μm SbnI with 100:1 unlabeled sbnC probe to labeled probe; lane 5, 25 μm SbnI with 100:1 unlabeled rpoB probe to labeled probe; lane 6, 25 μm SbnG.

SbnI Binds Heme

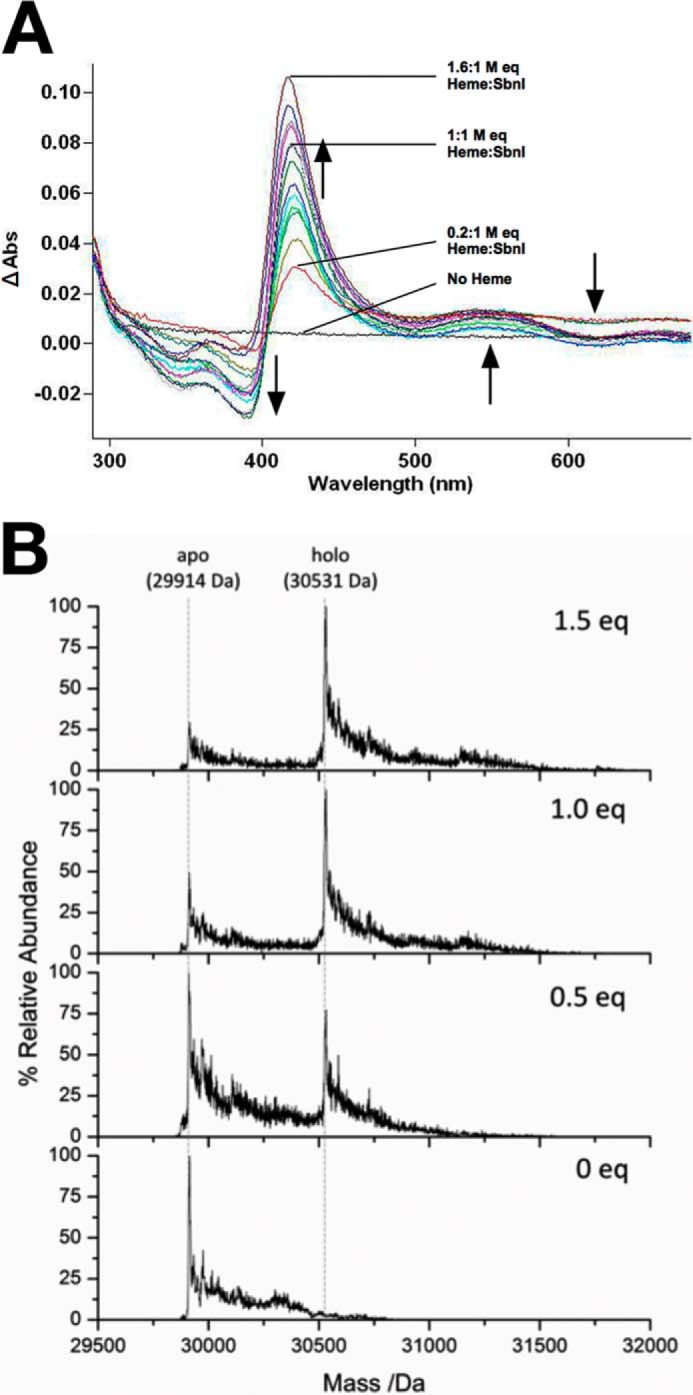

The iron response regulator (Irr) protein of Bradyrhizobium spp. is a DNA-binding transcription factor regulating gene expression. The protein binds heme, which results in substantially decreased affinity for DNA (36, 37). This interaction is aided by an HXH motif located central to the Irr protein (38). Because SbnI contains the sequence HIHEH (i.e. tandem HXH motif) at its extreme N terminus, we investigated the possibility that, in similar fashion to Irr, SbnI was capable of an interaction with heme. Heme titration experiments were performed using both UV-Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 9A) and ESI-MS (Fig. 9B), and both techniques demonstrated that SbnI was indeed capable of binding to heme, with saturation occurring at approximately a 1.5:1 heme to protein ratio.

FIGURE 9.

SbnI binds heme. A, UV-visible difference absorbance spectra recorded following addition of increasing concentrations of heme to 1 μm SbnI in 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4. The absorption spectra were measured at 22 °C. The shift in spectral maxima coincident with the absorption spectrum of the protein-bound heme with increasing heme concentrations is indicated by arrows. The concentration of the heme at the end of the titration was 1.6 μm, where the increase in Soret peak is due to nonspecific heme stacking, as SbnI optimally binds heme at a 1:1 molar ratio heme/SbnI, as indicated by ESI-MS data shown in B. B, deconvoluted electrospray ionization mass spectral data of SbnI in 300 mm ammonium formate, pH 7.4, and 2 mm DTT as a function of increasing heme stoichiometry (0 mol eq (bottom) to 1.5 mol eq added heme (top)). The heme solution was freshly prepared prior to the measurement. The apo-SbnI has a mass of 29,914 Da. Heme binding to the holo-SbnI results in a new mass at 30,531 Da. The relative abundance of the apo-SbnI decreases as the heme concentration increases. The holo-SbnI with a single heme bound (mass 30,531 Da) is the major species even with excess heme (top).

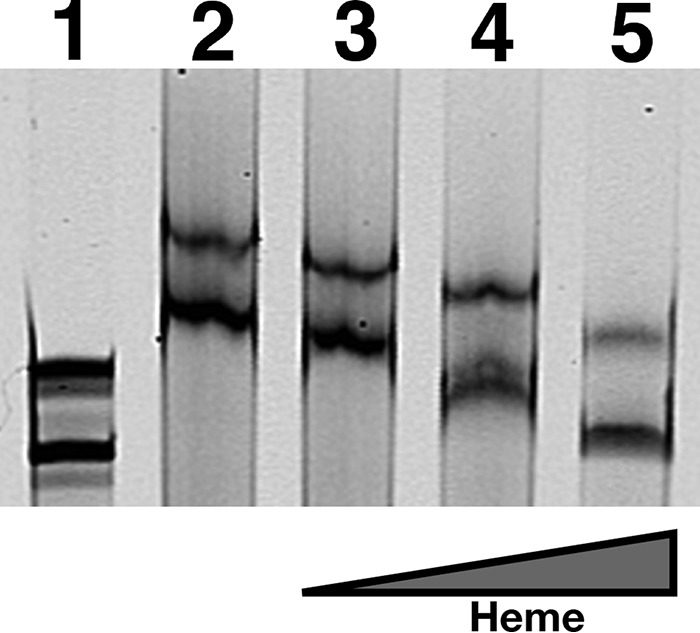

Heme Obviates the SbnI-DNA Interaction

Given that SbnI is capable of binding both DNA and heme, we next sought to determine whether the interaction of SbnI with heme would alter its DNA binding properties, as it does with the Irr protein (37). To examine this, EMSAs were repeated using SbnI protein that was pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of heme. As shown in Fig. 10, the ability of SbnI to bind the sbnC DNA fragment was diminished with increasing concentrations of heme. Moreover, at a 1:1 molar ratio of protein to heme, DNA binding was completely inhibited (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Heme decreases affinity of SbnI for DNA. EMSA was performed as described for Fig. 8. Each sample contained 120 ng of the fluorescently labeled, double-stranded sbnC probe. Lane 1, DNA alone; lane 2, 25 μm SbnI; lane 3, 25 μm SbnI with 0.2:1 molar equivalent of heme to SbnI; lane 4, 25 μm SbnI with 0.5:1 eq of heme to SbnI; lane 5, 25 μm SbnI with 1:1 eq of heme to SbnI.

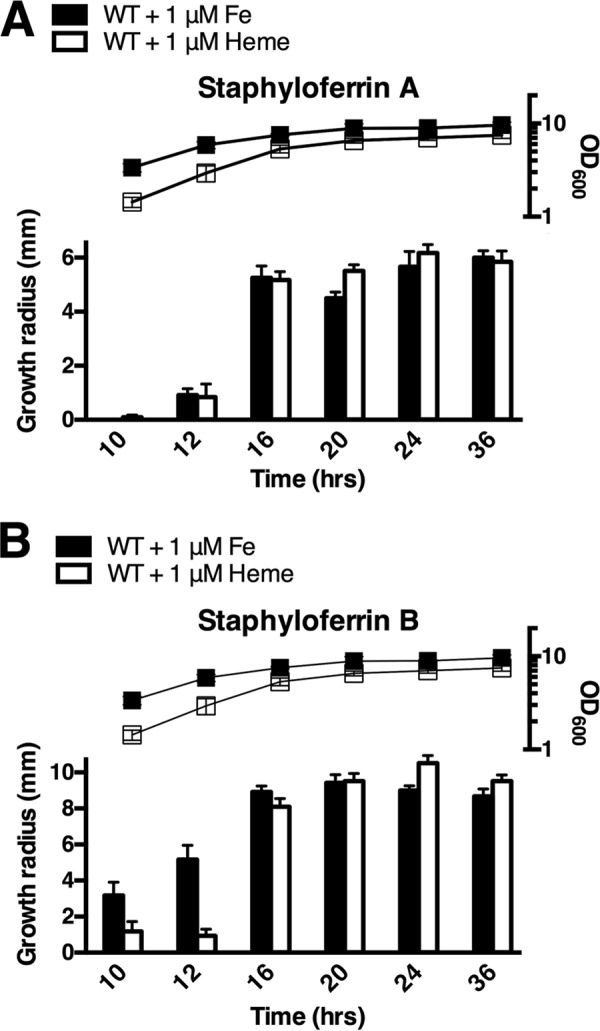

Extracellular Heme Controls SB Synthesis

Although previous studies have demonstrated that S. aureus preferentially uses heme as an iron source (12), no studies have yet investigated the effect of heme on the synthesis of siderophores. Moreover, our data showing that SbnI is required for SB synthesis, and that heme obviated the DNA-binding ability of SbnI, led us to investigate how exogenously supplied heme may affect SB production.

To investigate the effects of heme on SA and SB production, a disc diffusion assay was performed to determine the relative amounts of each siderophore produced during growth of WT RN6390 in cTMS medium with either 1 μm FeCl3 (WT + Fe) or 1 μm heme (WT + heme). As described previously, the spent culture supernatants were spotted onto cTMS agar seeded with either sir or hts mutants to examine for the presence of SA or SB, respectively. As shown in Fig. 11A, the relative amounts of SA were comparable between supernatants from cultures grown in equivalent concentrations of FeCl3 versus heme. However, in agreement with the results described above, spent supernatants from cultures grown in heme, versus FeCl3, showed decreased amounts of SB during the early stages of growth, until at least the 16-h time point, a point when cultures were entering stationary phase. As opposed to the global suppressive ability of iron on iron-regulated genes, in a Fur-dependent fashion, our results indicate that heme specifically suppresses the synthesis of SB. We suggest that this regulation functions through heme's ability to inhibit DNA binding of SbnI, whose function is required for transcription of genes within the sbn operon (i.e. SB biosynthesis/secretion genes).

FIGURE 11.

Heme reduces staphyloferrin B production. Disc diffusion assay was performed as described previously, and all strains were grown in cTMS with either the addition of 1 μm FeCl3 or 1 μm heme. A, growth radius from SA secretion was comparable between WT + heme and WT + Fe for all time points. B, disc diffusion assay demonstrating reduced amount of SB in culture supernatants at 10 and 12 h of growth from WT grown in 1 μm heme when compared with WT grown in 1 μm FeCl3. Optical density of cultures at the various time points is plotted above the disc diffusion assay results (right y axis).

Discussion

The capacity of S. aureus to establish an infection is reliant on its ability to acquire iron from the host. The expression of many genes encoding proteins involved in iron metabolism is “iron-regulated” through the activity of the global regulatory protein, Fur. Fur-mediated regulation of gene expression is widespread in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (29, 30). Indeed, expression of the sbn operon is repressed by Fur during growth in iron-replete media. However, S. aureus is unlikely to encounter iron-replete conditions during infection of the host, given that the host actively sequesters iron from pathogens (39, 40). Moreover, because S. aureus possesses multiple iron acquisition strategies, all regulated at a minimum by Fur, additional mechanisms are likely to exist for fine-tuning the response of S. aureus to the availability of different iron chelates during iron starvation conditions. This is especially true in light of previous work demonstrating that S. aureus prefers to utilize heme as an iron source (12). Our identification of SbnI as a transcriptional regulator of sbn operon expression, in response to heme, is the first such identification of a molecular mechanism underpinning a manner by which S. aureus “senses” heme to control siderophore synthesis. The model provides some mechanistic insight in support of the observations of Skaar et al. (12), who reported that heme is the preferred iron source of S. aureus.

In this study, we show that SbnI is a regulatory protein with DNA and heme binding capabilities. SbnI regulates transcript levels of genes in the sbn operon, particularly genes including sbnD and downstream of sbnD. Thus, under iron starvation conditions, SbnI is required to allow expression of the gene encoding the SB efflux pump, SbnD, and essential biosynthetic genes, sbnE–H. This ultimately serves to increase production of SB but also to ensure that, once SB synthesis has been initiated by the activity of SbnA and SbnB enzymes (19–21), the efflux pump is expressed. This ultimately ensures that SB, and potentially its intermediates, does not accumulate in the cytoplasm. Regulatory control of efflux versus biosynthesis has been documented for the biosynthesis/efflux of the antibiotic actinorhodin in Streptomyces coelicolor (41). Ensuring expression of the efflux pump prior to synthesis of the end product ultimately serves to “protect” the cell from an overabundance of cytosolic antibiotics. SB is a high affinity iron chelator that, if located in high abundance in the cell cytosol, could negatively impact cellular function by binding to intracellular iron. Thus, the SbnI-dependent up-regulation of sbnD and downstream genes may serve to ensure expression of the efflux pump prior to complete synthesis of the SB molecule. The early steps of SB synthesis, which result in the formation of l-Dap by SbnA and SbnB (20, 21), may also be important for SbnI function, and we are currently investigating the possibility that SB intermediates, including l-Dap, work as co-regulators by binding with SbnI.

This is the first study to investigate the importance of SbnI in siderophore synthesis, and our data clearly implicate a role for SbnI in transcriptional control from regions within the sbn operon. The mechanisms underlying the function of SbnI in DNA binding and transcriptional control are areas of interest. The similarity of SbnI with ParB/Spo0J may provide some insight. The Spo0J protein has been demonstrated to bind DNA at disparate locations and, along with its ability to self-associate, can cause DNA bending within higher order nucleoprotein complexes (42). In the case of SbnI, there may be additional locations throughout the sbn operon that SbnI may bind in forming regulatory complexes that control transcription. These, along with the identification of exact nucleotide-binding sequences for SbnI, are priorities for our ongoing studies.

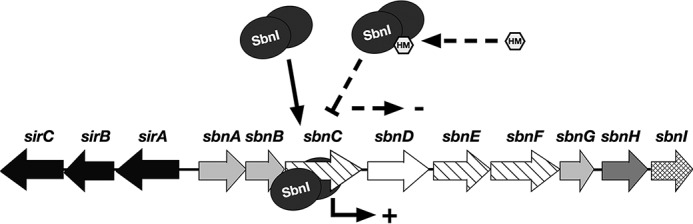

Along with demonstrating that SbnI is a regulatory protein of SB efflux and biosynthesis, we suggest that SbnI controls production of SB in response to heme because in this study we showed that SbnI is capable of binding to heme, and when complexed with heme it is unable to interact with nucleic acid, at least the region we identified within the sbnC coding region. In this manner, SbnI may represent a novel mechanism by which S. aureus regulates siderophore synthesis and utilization in response to the presence of heme (Fig. 12), perhaps as a sophisticated method to transition from SB-mediated iron uptake to heme-mediated iron uptake. In support of this hypothesis, we were able to demonstrate that providing extracellular heme to S. aureus resulted in a decrease in SB production but not SA production. Although we favor the hypothesis that this effect is mediated through SbnI, our data cannot as of yet conclusively support this contention. When provided exogenous heme, it is difficult to determine how much of the heme is taken into the cell and remains intact and capable of binding to proteins like SbnI. Moreover, it is still unknown the role that intracellular heme biosynthesis plays in regulating metabolic processes such as siderophore biosynthesis. Ultimately, the ability to sense intracellular heme may be a mechanism whereby S. aureus conserves energy by not utilizing siderophore-mediated iron uptake unnecessarily when heme can be used as the primary iron source. Should heme no longer be accessible as an iron source, we hypothesize that “active” SbnI would allow transcription of downstream sbn genes and that pre-formed l-Dap in the cell would allow for a rapid transition to SB-mediated iron uptake. The fine-tuning of SB and heme uptake systems in S. aureus is of interest because both sbn and isd genes have been implicated in virulence in S. aureus models of infection (16, 25, 26, 43–46).

FIGURE 12.

Proposed model of SbnI-mediated gene regulation in response to heme. In conditions of low iron and low heme, SbnI dimer binds to DNA within the sbnC coding region and promotes expression of genes sbnD–H. Under conditions of low iron and high heme, heme binds to SbnI, preventing binding of SbnI to DNA and thereby resulting in decreased expression of genes sbnD–H.

Author Contributions

D. E. H. conceived and coordinated the study. T. B. P. and M. J. S. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in Fig. 9. H. A. L. and C. L. M. performed experiments. H. A. L. and D. E. H. wrote the paper. All authors analyzed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. C. Beasley, H. Zhang, R. Young, and L.-A. Briere for providing reagents and/or expertise to this study. We also thank Michael E. P. Murphy for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to D. E. H.) and by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council (to M. J. S.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

- NIS

- non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-independent siderophore

- SA

- staphyloferrin A

- SB

- staphyloferrin B

- Fur

- ferric uptake regulator

- l-Dap

- l-2,3-diamino-propionic acid

- qPCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- cTMS

- Chelex-100-treated Tris minimal succinate

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA end

- UV-Vis

- UV-visible

- EDDHA

- ethylenediamine-N,N′-bis(2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid.

References

- 1.Mediavilla J. R., Chen L., Mathema B., and Kreiswirth B. N. (2012) Global epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 588–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichol K. A., Adam H. J., Hussain Z., Mulvey M. R., McCracken M., Mataseje L. F., Thompson K., Kost S., Lagacé-Wiens P. R., Hoban D. J., Zhanel G. G., and Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Alliance (CARA). (2011) Comparison of community-associated and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canada: results of the CANWARD 2007–2009 study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 69, 320–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garnier F., Tristan A., François B., Etienne J., Delage-Corre M., Martin C., Liassine N., Wannet W., Denis F., and Ploy M. C. (2006) Pneumonia and new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 498–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreillon P., Que Y. A., and Bayer A. S. (2002) Pathogenesis of streptococcal and staphylococcal endocarditis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 16, 297–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson A. P., Pearson A., and Duckworth G. (2005) Surveillance and epidemiology of MRSA bacteraemia in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56, 455–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Posey J. E., and Gherardini F. C. (2000) Lack of a role for iron in the Lyme disease pathogen. Science 288, 1651–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imbert M., and Blondeau R. (1998) On the iron requirement of lactobacilli grown in chemically defined medium. Curr. Microbiol. 37, 64–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratledge C., and Dover L. G. (2000) Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 881–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hentze M. W., Muckenthaler M. U., and Andrews N. C. (2004) Balancing acts: molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 117, 285–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammer N. D., and Skaar E. P. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus iron acquisition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 129–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheldon J. R., and Heinrichs D. E. (2015) Recent developments in understanding the iron acquisition strategies of Gram-positive pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 592–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skaar E. P., Humayun M., Bae T., DeBord K. L., and Schneewind O. (2004) Iron-source preference of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Science 305, 1626–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazmanian S. K., Skaar E. P., Gaspar A. H., Humayun M., Gornicki P., Jelenska J., Joachmiak A., Missiakas D. M., and Schneewind O. (2003) Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 299, 906–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muryoi N., Tiedemann M. T., Pluym M., Cheung J., Heinrichs D. E., and Stillman M. J. (2008) Demonstration of the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) heme transfer pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28125–28136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grigg J. C., Ukpabi G., Gaudin C. F., and Murphy M. E. (2010) Structural biology of heme binding in the Staphylococcus aureus Isd system. J. Inorg. Biochem. 104, 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pishchany G., Sheldon J. R., Dickson C. F., Alam M. T., Read T. D., Gell D. A., Heinrichs D. E., and Skaar E. P. (2014) IsdB-dependent hemoglobin binding is required for acquisition of heme by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 1764–1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Challis G. L. (2005) A widely distributed bacterial pathway for siderophore biosynthesis independent of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. ChemBioChem. 6, 601–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raymond K. N., Dertz E. A., and Kim S. S. (2003) Enterobactin: an archetype for microbial iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3584–3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung J., Beasley F. C., Liu S., Lajoie G. A., and Heinrichs D. E. (2009) Molecular characterization of staphyloferrin B biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 594–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beasley F. C., Cheung J., and Heinrichs D. E. (2011) Mutation of l-2,3-diaminopropionic acid synthase genes blocks staphyloferrin B synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 11, 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobylarz M. J., Grigg J. C., Takayama S. J., Rai D. K., Heinrichs D. E., and Murphy M. E. (2014) Synthesis of l-2,3-diaminopropionic acid, a siderophore, and antibiotic precursor. Chem. Biol. 21, 379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotton J. L., Tao J., and Balibar C. J. (2009) Identification and characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus gene cluster coding for staphyloferrin A. Biochemistry 48, 1025–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beasley F. C., Vinés E. D., Grigg J. C., Zheng Q., Liu S., Lajoie G. A., Murphy M. E., and Heinrichs D. E. (2009) Characterization of staphyloferrin A biosynthetic and transport mutants in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 947–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannauer M., Sheldon J. R., and Heinrichs D. E. (2015) Involvement of major facilitator superfamily proteins SfaA and SbnD in staphyloferrin secretion in Staphylococcus aureus. FEBS Lett. 589, 730–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dale S. E., Doherty-Kirby A., Lajoie G., and Heinrichs D. E. (2004) Role of siderophore biosynthesis in virulence of Staphylococcus aureus: identification and characterization of genes involved in production of a siderophore. Infect. Immun. 72, 29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanses F., Roux C., Dunman P. M., Salzberger B., and Lee J. C. (2014) Staphylococcus aureus gene expression in a rat model of infective endocarditis. Genome Med. 6, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung J., Murphy M. E., and Heinrichs D. E. (2012) Discovery of an iron-regulated citrate synthase in Staphylococcus aureus. Chem. Biol. 19, 1568–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldon J. R., Marolda C. L., and Heinrichs D. E. (2014) TCA cycle activity in Staphylococcus aureus is essential for iron-regulated synthesis of staphyloferrin A, but not staphyloferrin B: the benefit of a second citrate synthase. Mol. Microbiol. 92, 824–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews S. C., Robinson A. K., and Rodríguez-Quiñones F. (2003) Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 215–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fillat M. F. (2014) The fur (ferric uptake regulator) superfamily: diversity and versatility of key transcriptional regulators. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 546, 41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhatt G., and Denny T. P. (2004) Ralstonia solanacearum iron scavenging by the siderophore staphyloferrin B is controlled by PhcA, the global virulence regulator. J. Bacteriol. 186, 7896–7904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flavier A. B., Ganova-Raeva L. M., Schell M. A., and Denny T. P. (1997) Hierarchical autoinduction in Ralstonia solanacearum: control of acyl-homoserine lactone production by a novel autoregulatory system responsive to 3-hydroxypalmitic acid methyl ester. J. Bacteriol. 179, 7089–7097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mesak L. R., Yim G., and Davies J. (2009) Improved lux reporters for use in Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid 61, 182–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper J. D., Hannauer M., Marolda C. L., Briere L. A., and Heinrichs D. E. (2014) Identification of a positively charged platform in Staphylococcus aureus HtsA that is essential for ferric staphyloferrin A transport. Biochemistry 53, 5060–5069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dumont M. E., Corin A. F., and Campbell G. A. (1994) Noncovalent binding of heme induces a compact apocytochrome c structure. Biochemistry 33, 7368–7378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamza I., Chauhan S., Hassett R., and O'Brian M. R. (1998) The bacterial Irr protein is required for coordination of heme biosynthesis with iron availability. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21669–21674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singleton C., White G. F., Todd J. D., Marritt S. J., Cheesman M. R., Johnston A. W., and Le Brun N. E. (2010) Heme-responsive DNA binding by the global iron regulator Irr from Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16023–16031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J., Ishimori K., and O'Brian M. R. (2005) Two heme binding sites are involved in the regulated degradation of the bacterial iron response regulator (Irr) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7671–7676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cassat J. E., and Skaar E. P. (2013) Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 13, 509–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nairz M., Haschka D., Demetz E., and Weiss G. (2014) Iron at the interface of immunity and infection. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tahlan K., Ahn S. K., Sing A., Bodnaruk T. D., Willems A. R., Davidson A. R., and Nodwell J. R. (2007) Initiation of actinorhodin export in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 951–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graham T. G., Wang X., Song D., Etson C. M., van Oijen A. M., Rudner D. Z., and Loparo J. J. (2014) ParB spreading requires DNA bridging. Genes Dev. 28, 1228–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reniere M. L., and Skaar E. P. (2008) Staphylococcus aureus haem oxygenases are differentially regulated by iron and haem. Mol. Microbiol. 69, 1304–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visai L., Yanagisawa N., Josefsson E., Tarkowski A., Pezzali I., Rooijakkers S. H., Foster T. J., and Speziale P. (2009) Immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus conferred by iron-regulated surface determinant protein IsdH. Microbiology. 155, 667–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torres V. J., Pishchany G., Humayun M., Schneewind O., and Skaar E. P. (2006) Staphylococcus aureus IsdB is a hemoglobin receptor required for heme iron utilization. J. Bacteriol. 188, 8421–8429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng A. G., Kim H. K., Burts M. L., Krausz T., Schneewind O., and Missiakas D. M. (2009) Genetic requirements for Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and persistence in host tissues. FASEB J. 23, 3393–3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreiswirth B. N., Löfdahl S., Betley M. J., O'Reilly M., Schlievert P. M., Bergdoll M. S., and Novick R. P. (1983) The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305, 709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peng H. L., Novick R. P., Kreiswirth B., Kornblum J., and Schlievert P. (1988) Cloning, characterization and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 170, 4365–4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charpentier E., Anton A. I., Barry P., Alfonso B., Fang Y., and Novick R. P. (2004) Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for Gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 6076–6085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]