Abstract

Consent is a legal requirement of medical practice and not a procedural formality. Getting a mere signature on a form is no consent. If a patient is rushed into signing consent, without giving sufficient information, the consent may be invalid, despite the signature. Often medical professionals either ignore or are ignorant of the requirements of a valid consent and its legal implications. Instances where either consent was not taken or when an invalid consent was obtained have been a subject matter of judicial scrutiny in several medical malpractice cases. This article highlights the essential principles of consent and the Indian law related to it along with some citations, so that medical practitioners are not only able to safeguard themselves against litigations and unnecessary harassment but can act rightfully.

Keywords: Doctor-patient relationship, Indian law, informed consent

INTRODUCTION

Legally, two or more persons are said to consent when they agree upon the same thing in the same sense.[1] Consent must be obtained prior to conducting any medical procedure on a patient. It may be expressed or implied by patient's demeanour. A patient who comes to a doctor for treatment implies that he is agreeable to general physical (not intimate) examination.[2] Express consent (verbal/written) is specifically stated by the patient. Express verbal consent may be obtained for relatively minor examinations or procedures, in the presence of a witness.[3] Express written consent must be obtained for all major diagnostic, anaesthesia and surgical procedures as it is the most undisputable form of consent.

ESSENTIAL PRINCIPLES OF A VALID CONSENT AND THE INDIAN LAW

A doctor must take the consent of the patient before commencing a treatment/procedure

Except in emergencies, informed consent should be obtained sometime prior to the procedure so that the patient does not feel pressurised or rushed to sign. On the day of surgery, the patient may be under extreme mental stress or under influence of pre-medicant drugs which may hamper his decision-making ability. Consent remains valid for an indefinite period, provided there is no change in patient condition or proposed intervention.[4] It should be confirmed at the time of surgery.[4]

Consent must be taken from the patient himself

The doctor before performing any procedure must obtain patient's consent.[5] No one can consent on behalf of a competent adult. In Dr. Ramcharan Thiagarajan Facs versus Medical Council of India case,[6] disciplinary action was awarded to the surgeon for not taking a proper informed consent for the entire procedure of kidney and pancreas transplant surgery from the patient. In some situations, beside patient consent, it is desirable to take additional consent of spouse. In sterilisation procedures, according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India guidelines, consent of spouse is not required.[7] The Medical Council of India (clause 7.16) however states that in case an operation carries the risk of sterility, the consent of both husband and wife is needed.[8] It is advisable to take consent of spouse when the treatment or procedure may adversely affect or limit sex functions, or result in death of an unborn child.[9] In case of minor, consent of person with parental responsibility should be taken.[10] In an emergency, the person in charge of the child at that time can consent in absence of parents or guardians (loco parentis).[11] In a medical emergency, life-saving treatment can be given even in absence of consent.

Refusing treatment in life-threatening situations due to non-availability of consent may hold the doctor guilty, unless there is a documented refusal to treatment by the patient. In Dr. TT Thomas versus Smt. Elisa and Ors case,[12] the doctor was held guilty of negligence for not operating on a patient with life-threatening emergency condition, as there was no documented refusal to treatment.

The patient should have the capacity and competence to consent

A person is competent to contract[13] if (i) he has attained the age of majority,[14] (ii) is of sound mind[15] and (iii) is not disqualified from contracting by any law to which he is subject. The legal age for giving a valid consent in India is 18 years.[14] A child >12 years can give a valid consent for physical/medical examination (Indian Penal Code, section 89).[3] Prior to performing any procedure on a child <18 years, it is advisable to take consent of a person with parental responsibility so that its validity is not questioned. If patient is incompetent, then consent can be taken from a surrogate/proxy decision maker who is the next of kin (spouse/adult child/parent/sibling/lawful guardian).[11]

Consent should be free and voluntary

Consent is said to be free[16] when it is not caused by coercion,[17] undue influence,[18] fraud,[19] misrepresentation,[20] or mistake.[21,22,23]

Consent should be informed

Consent should be on the basis of adequate information concerning the nature of the treatment procedure.[5] Consent should be informed and based on intelligent understanding. The doctor must disclose information regarding patient condition, prognosis, treatment benefits, adverse effects, available alternatives, risk of refusing treatment and the approximate treatment cost. He should encourage questions and answer all queries.[2]

If the possibility of a risk, including the risk of death, due to performance of a procedure or its refusal is remote or only theoretical, it need not be explained.[5] Exceptions to physician's duty to disclose include[24] : (i) Patient refusal to be informed; this should be documented. (ii) If the doctor feels that providing information to a patient who is anxious or disturbed would not be processed rationally by him and is likely to psychologically harm him, the information may be withheld from him (therapeutic privilege); he should then communicate with patient's close relative, family doctor or both.

The “adequate information” must be furnished by the doctor (or a member of his team) who treats the patient.[5]

Information imparted should enable the patient to make a balanced judgment as to whether he should submit himself to the particular treatment or not.[5]

Consent should be procedure specific

Consent given only for a diagnostic procedure, cannot be considered as consent for the therapeutic treatment.[5] Consent given for a specific treatment procedure will not be valid for conducting some other procedure.[5] In Samira Kohli versus Dr. Prabha Manchanda and Anr case,[5] the doctor was held negligent for performing an additional procedure on the patient without taking her prior consent. An additional procedure may be performed without consent only if it is necessary to save the life or preserve the health of the patient and it would be unreasonable to delay, until patient regains consciousness and takes a decision.[5]

A common consent for diagnostic and operative procedures may be taken where they are contemplated.[5]

Consent obtained during the course of surgery is not acceptable

In Dr. Janaki S Kumar and Anr versus Mrs. Sarafunnisa case,[25] in an allegation of performing sterilisation without consent, it was contended that consent was obtained during the course of surgery. The commission held that the patient under anaesthesia could neither understand the risk involved nor could she give a valid consent.

Consent for blood transfusion

When blood transfusion is anticipated, a specific written consent should be taken,[24] exception being an emergency situation where blood transfusion is needed to save life and consent cannot be attempted.[26] In M. Chinnaiyan versus Sri. Gokulam Hospital and Anr case,[27] court awarded compensation as patient was transfused blood in the absence of specific consent for blood transfusion.

Consent for examining or observing a patient for educational purpose

Prior to examining or observing patients for educational purpose, their consent must be taken.[28]

Blanket consent is not valid

Consent should be procedure specific. An all-encompassing consent to the effect ‘I authorize so and so to carry out any test/procedure/surgery in the course of my treatment’ is not valid.[29]

Fresh consent should be taken for a repeat procedure

A fresh written informed consent must be obtained prior to every surgical procedure that includes re-exploration procedure. In Dr. Shailesh Shah versus Aphraim Jayanand Rathod case,[30] the surgeon was found deficient in service and was liable for compensation as he had performed a re-exploration surgery without a written consent from the patient.

Surgical consent is not sufficient to cover anaesthesia care

The surgeons are incapable to discuss the risks associated with anaesthesia. Informed consent for anaesthesia must be taken by the anaesthesia provider as only he can impart anaesthesia related necessary information and explain the risks involved. It may be documented by the anaesthesiologist on the surgical consent form by a handwritten note, or on a separate anaesthesia consent form.[31]

Patient has the right to refuse treatment

Competent patients have the legal and moral right to refuse treatment, even in life-threatening emergency situations.[31] In such cases informed refusal must be obtained and documented, over the patient's witnessed signature.[32] It may be advisable that two doctors document the reason for non-performance of life-saving surgery or treatment as express refusal by the patient or the authorised representative and inform the hospital administrator about the same.

To detain an adult patient against his will in a hospital is unlawful.[9] If a patient demands discharge from hospital against medical advice, this should be recorded, and his signature obtained.[9]

Unilaterally executed consents are void

Consent signed only by the patient and not by the doctor is not valid.[33]

Witnessed consents are legally more dependable

The role of a witness is even more important in instances when the patient is illiterate, and one needs to take his/her thumb impression.[34]

Consent should be properly documented

Video-recording of the informed consent process may also be done but with a prior consent for the same. This should be documented. It is commonly done for organ transplant procedures. If consent form is not signed by the patient or is amended without his signed authorisation, it can be claimed that the procedure was not consented to.[10]

Patient is free to withdraw his consent anytime

When consent is withdrawn during the performance of a procedure, the procedure should be stopped. The doctor may address to patient's concerns and may continue the treatment only if the patient agrees. If stopping a procedure at that point puts patient's life in danger, the doctor may continue with the procedure till such a risk no longer exists.[10]

Consent for illegal procedures is invalid

There can be no valid consent for operations or procedures which are illegal.[24] Consent for an illegal act such as criminal abortion is invalid.[9]

Consent is no defence in cases of professional negligence.[9]

HOW TO OBTAIN A VALID CONSENT AND CONSENT FORMAT

Always maintain good communication with your patient and provide adequate information to enable him make a rational decision.[35] It is preferable to take consent in patient's vernacular language. It may be better to make him write down his consent in the presence of a witness.[34] It is desirable to use short and simple sentences and non-medical terminology that is written/typed legibly.[36] Patient information sheets (PIS) depicting procedure related information, including pre-operative and post-operative pre-cautions in patient's understandable local language with pictorial representation may facilitate the informed consent process. These may help in providing consistently accurate information to the patients.[35] PIS should be handed over to the patients after explaining the contents. Even videos may be used as an aid in increasing patient understanding.[37]

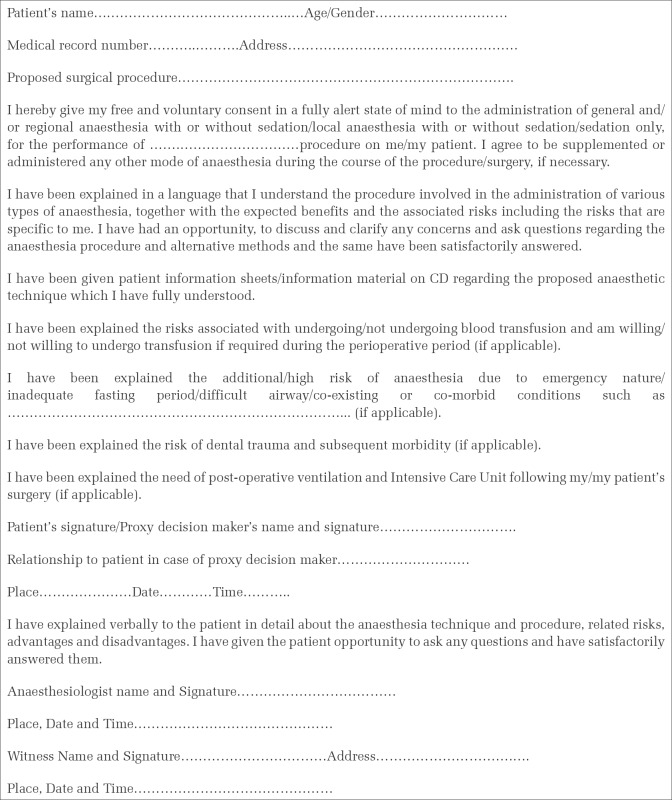

Though there is no standard consent format, it may include the following [e.g., Figure 1]:[38]

Figure 1.

Anaesthesia informed consent form

Date and time

Patient related: Name, age and signature of the patient/proxy decision maker

Doctor related: Name, registration number and signature of the doctor

Witness: Name and signature of witness

Disease-related: Diagnosis along with co-morbidities if any

Surgical procedure related: Type of surgery (elective/emergency), nature of surgery with antecedent risks and benefits, alternative treatment available, adverse consequences of refusing treatment

Anaesthesia related: Type of anaesthesia (general and/or regional, local anaesthesia, sedation) including risks

Blood transfusion: Requirement and related risks

Special risks: Need for post-operative ventilation, intensive care, etc

Document the fact that patient and relatives were allowed to ask questions, and their queries were answered to their satisfaction.

CONSENT IN RELATION TO PUBLICATION

A registered medical practitioner is not permitted to publish photographs or case reports of his/her patients without their consent, in any medical or another journal in a manner by which their identity could be revealed. However, in case the identity is not disclosed, consent is not needed (clause 7.17).[8]

CONSENT IN RELATION TO MEDICAL RESEARCH

Consent taken from the patient for the drug trial or research should be as per the Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines[39]; otherwise it shall be construed as misconduct (clause 7.22).[8]

COMMON FALLACIES IN THE CONSENT PROCESS

The anaesthesiologist must ensure that consent is given maximum importance, and all the legal formalities are followed before agreeing to provide the services. Following are some frequent mistakes and omissions that can cost him/her dearly in the event of a mishap:

Procedure is considered trivial, and consent is not taken

Consent of relative is taken instead of the patient, even when patient is a competent adult.

Consenting person is minor, intoxicated or of unsound mind

Blanket consent is taken.

It is not procedure specific

Consent for blood transfusion is not obtained.

Fresh consent is not taken for a repeat procedure

Procedure related necessary information is not given

Even if the information given, it is not documented

Consent lacks the signature of the treating doctor

Consent is not witnessed

Alterations or additions are made in the consent form without patient's signed authorisation.

SUMMARY

It is not only ethical to impart correct and necessary information to a patient prior to conducting any medical procedure, but it is also important legally. This communication should be documented. Even professional indemnity insurance may not cover for lapses in obtaining a valid consent, considering it to be an intentional assault.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contribution and irreplaceable advice extended to us during the preparation of this article by Mr. M Wadhwani, Advocate.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Indian Contract Act, Sec 13; 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act,1872.-2386 .

- 2.Sharma G, Tandon V, Chandra PS. Legal sanctity of consent for surgical procedures in India. Indian J Neurosurg. 2012;1:139–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao NG. Textbook of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2010. Ethics of medical practice; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson OA, Wearne IM. Informed consent for elective surgery - what is best practice? J R Soc Med. 2007;100:97–100. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samira Kohli vs. Dr. Prabha Manchanda and Anr on 16 January, 2008. Civil Appeal No. 1949 of 2004. (2008) 2 SCC 1; AIR 2008 SC 1385. [Accessed on 2014 May 9]. Available from: http://www.indiankanoon.org/doc/438423/

- 6.Dr. Ramcharan Thiagarajan Facs vs Medical Council of India on 3 April, 2014. Karnataka High Court. Writ Petition No. 11207/2013 (GM-RES) [Accessed on 2014 July 11]. Available from: http://www.indiankanoon.com/doc/10293098/

- 7.Standards for Female Sterilization (1.4.4), Standards for Male Sterilization (2.4.4) Standards for Female and Male Sterilization Services. Research Studies and Standards Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. 2006. Oct, [Accessed on 2014 Mar 16]. Available from: http://www.nrhmtn.gov.in/modules/Guidelines%20for%20Standard%20for%20 female%20 & %20 male%20sterilization%20services.pdf .

- 8.Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations, 2002. Published in Part-III, Section 4 of the Gazette of India, dated 6th April, 2002, Amended up to December. 2010.

- 9.Reddy KS, Murty OP. The Essentials of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology. 32nd ed. Hyderabad: K Suguna Devi; 2013. Medical law and ethics; pp. 22–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herring J. Medical Law and Ethics. 4th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2012. Consent to treatment; pp. 149–220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora V. Role of consent in medical practice. [Accessed on 2014 Mar 21];J Evol Med Dent Sci 2013. 2:1225–9. Available from: http://www.jemds.com/data_pdf/vijay%20arora-ROLE%20OF%20CONSENT%20IN%20MEDICAL.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dr. TT Thomas vs Smt Elisa and Ors on 11 August, 1986. Kerala High Court. AIR 1987 Ker 52: 1986 Ker LT 1026 (DB) [Accessed on 2014 Jun 2]. Available from: http://www.indiankanoon.org/doc/600254/

- 13.Indian Contract Act, Sec 11. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872.-2384 .

- 14.Indian Majority Act. 1875. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://admis.hp.nic.in/himpol/Citizen/LawLib/C0141.htm .

- 15.Indian Contract Act, Sec 12. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872.-2385 .

- 16.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 14. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872.-2387 .

- 17.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 15. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872-2388 .

- 18.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 16. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872-5173 .

- 19.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 17. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872-2390 .

- 20.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 18. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1270593/

- 21.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 20. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872-5178 .

- 22.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 21. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872-2395 .

- 23.The Indian Contract Act, Sec 22. 1872. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indianlawcases.com/Act-Indian.Contract.Act.,1872-5180 .

- 24.Kannan JK, Mathiharan K. Legal and ethical aspects of medical practice. In: Modi A, editor. Textbook of Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology. 24th ed. Nagpur: Lexis Nexis Butterworths Wadhwa; 2012. pp. 61–118. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dr. Janaki S Kumar and Anr vs Mrs. Sarafunnisa on 21 June, 1999. Kerala State Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission, Thiruvananthapuram. Appeal No. 850 of 1998. (1999) I CPJ 66.

- 26.Kekre NS. Medical law and the physician. Indian J Urol. 2008;24:135–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.40602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.M. Chinnaiyan vs. Sri. Gokulam Hospital and Anr on 25 September, 2006. III (2007) CPJ 228 NC. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.indiankanoon.org/doc/1919829/

- 28.Doyal L. Closing the gap between professional teaching and practice. BMJ. 2001;322:685. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satyanarayana Rao KH. Informed consent: An ethical obligation or legal compulsion? J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2008;1:33–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.41159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dr Shailesh Shah vs Aphraim Jayanand Rathod. National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission New Delhi, FA No. 597 of 1995. From the order dated 8 Nov, 1995 in complaint No. 31/94, State Commission Gujarat. [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.ncdrc.nic.in/fa59795.html .

- 31.Waisel DB. Legal aspects of anesthesia care. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Young WL, editors. Miller's Anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia USA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. pp. 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tewari A, Garg S. Informed consent and anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:311–2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bastia BK, Kuruvilla A, Saralaya KM. Validity of consent-A review of statutes. Indian J Med Sci. 2005;59:74–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bastia BK. Consent to treatment: Practice vis-à-vis principle. Indian J Med Ethics. 2008;5:113–4. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2008.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalantri SP. Informed consent and the anaesthesiologist. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:94–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaushik JS, Narang M, Agarwal N. Informed consent in pediatric practice. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:1039–46. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tompsett E, Afifi R, Tawfeek S. Can video aids increase the validity of patient consent? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:680–2. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.698329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh D. Singh D. Informed vs. Valid consent: Legislation and responsibilities. [Accessed on 2014 Aug 21];Indian J Neurotrauma. 2008 5:105–8. Available from: http://www.medind.nic.in/icf/t08/i2/icft08i2p105.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants. New Delhi: Published by: Director General Indian Council of Medical Research; 2006. [Accessed on 2014 Mar 3]. eral Ethical Issues; pp. 21–33. Available from: http://www.icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf . [Google Scholar]