Abstract

Objective

To characterize work-related asthma by gender.

Methods

We analyzed state-based sentinel surveillance data on confirmed work-related asthma cases collected from California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey during 1993–2008. We used Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact Test statistics to compare select characteristics between females and males.

Results

Of the 8239 confirmed work-related asthma cases, 60% were female. When compared to males with work-related asthma, females with work-related asthma were more likely to be identified through workers’ compensation (14.8% versus 10.6%) and less likely to be identified through hospital data (14.2% versus 16.9%). Moreover, when compared to males, females were more likely to have work-aggravated asthma (24.4% versus 13.5%) and less likely to have new-onset asthma (48.0% versus 56.5%). Females were also more likely than males with work-related asthma to work in healthcare and social assistance (28.7% versus 5.2%), educational services (11.8% versus 4.2%), and retail trade (5.0% versus 3.9%) industries and in office and administrative support (20.0% versus 4.0%), healthcare practitioners and technical (13.4% versus 1.6%), and education training and library (6.2% versus 1.3%) occupations. Agent groups most frequently associated with work-related asthma were miscellaneous chemicals (20.3%), cleaning materials (15.3%), and indoor air pollutants (14.9%) in females and miscellaneous chemicals (15.7%), mineral and inorganic dusts (13.2%), and pyrolysis products (12.7%) in males.

Conclusions

Among adults with work-related asthma, males and females differ in terms of workplace exposures, occupations, and industries. Physicians should consider these gender differences when diagnosing and treating asthma in working adults.

Keywords: Gender differences, occupational asthma, reactive airways dysfunction syndrome, surveillance, work-related asthma, work-aggravated asthma

Introduction

Asthma, a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, affects over 18.7 million adults in the United States [1]. The prevalence of current asthma is higher in adult females (9.7%) when compared to adult males (5.7%) [1]. In addition, females with asthma have more severe and more frequent asthma symptoms, increased activity limitation due to asthma, poorer asthma-related quality of life, and increased healthcare utilization when compared to males [2,3].

Work-related asthma, a subset of asthma, includes newonset asthma (asthma caused by workplace exposures to sensitizers or irritants) and work-aggravated asthma (preexisting asthma worsened by workplace exposures) [4]. An estimated 7% to 51% (median = 17.6%) of adult asthma is caused by occupational exposures such as vapors, gas, dust, and fumes [5] and approximately 13% to 58% (median = 21.5%) of adult asthma is worsened by workplace exposures [6]. Studies with separate estimates of the occupational attributable risk for asthma for males and females found a higher median occupational attributable risk for females (11.5%, range 3.9–20.0%) than for males (9.1%, range 6.0–29.0%) [7–12]. However, other studies have shown that occupational exposures are associated with a higher risk for adult-onset asthma in males than in females [13–15]. Although gender differences in work-related asthma may be due to differences in many factors, including workplace exposures, most work-related asthma surveillance data are not stratified by gender, an issue that was raised in 2007 during the Third Jack Pepys Workshop on Asthma in the Workplace [16].

Males and females tend to have different jobs, different responsibilities within the same occupation, different exposures, and varying exposure levels [17]. For example, males are more likely to work in construction and females are more likely to work in health-related occupations [18]. The characteristics of exposure, even within the same job, and the impact of the exposure on health may also differ by gender [15,19]. Dumas and colleagues found that the frequency and intensity of exposure to cleaning products in hospital workers was higher among females than males [19]. Moreover, in snow crab processing, female workers were significantly more likely than male workers to be exposed to allergens and to receive a diagnosis of work-related asthma [17]. In swine processing operations, asthma was more prevalent among atopic female swine workers than in atopic male swine workers [20].

While gender differences in adult asthma have been well characterized, information on gender differences in work-related asthma in the United States is limited. The objective of this study was to characterize gender differences in work-related asthma using state-based sentinel surveillance data from 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2008 from California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey.

Methods

For this study, we used 1993–2008 state-based sentinel work-related asthma surveillance program (formerly referred to as the Sentinel Event Notification System for Occupational Risks, or SENSOR) data from California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey [4]. For surveillance purposes, confirmation of work-related asthma requires a healthcare professional’s diagnosis consistent with asthma, and an association between symptoms of asthma and work [4]. Surveillance systems in each state identify potential cases of work-related asthma using a combination of healthcare professional reports and workers’ compensation, emergency department, hospital discharge, and poison control center data. Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey actively solicit healthcare professional reports while California uses an existing passive healthcare professional-based occupational injury and illness reporting system.

After receiving a report, states attempted to reach individuals with potential work-related asthma for telephone interviews to collect additional information on the interviewee’s demographics, asthma symptoms in relation to work, industry and occupation, and asthma-related exposures. Confirmed cases of work-related asthma were classified as new-onset asthma, work-aggravated asthma, or confirmed but unclassified work-related asthma. New-onset asthma was further classified into occupational asthma or reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (RADS); a condition induced by a onetime, high-level irritant exposure at work, with symptoms that occur within 24 hours and persist for at least three months. Further details of the classification schemes have been previously described [4]. Information on industry and occupation was coded using the 2002 North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) and the 2000 Bureau of Census Occupation Codes (COC), respectively. To determine if there were occupational gender differences within the same industry, we examined gender differences in major occupation groups within major industry groups reported. For simplicity, we only examined gender differences in the ten most common major occupation and industry groups reported.

For this analysis, we examined up to three reported putative agents associated with work-related asthma for each individual. Agents were coded using the Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics (AOEC) exposure codes [21]. Because of the large number of reported putative agents associated with work-related asthma, we grouped them using AOEC categories that contain agents of similar use or chemical nature. We calculated percentages of individuals associated with at least one agent in a specific agent category using the total number of individuals with work-related asthma separately for females and males. For simplicity, this manuscript only reports on the ten most frequently reported exposures by AOEC agent categories. We used SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for analyses. To compare select characteristics between females and males, chi-square and Fisher’s Exact Test statistics were used and considered statistically significant at p value < 0.05.

Results

During 1993–2008, a total of 8239 confirmed cases of work-related asthma were identified through the state-based sentinel surveillance systems in California, Massachusetts, Michigan and New Jersey (Table 1). Two individuals had missing information on gender and were excluded from further analysis. The primary source of case ascertainment was healthcare professional reports (70.3%). Most individuals were classified as having new-onset asthma (51.3%), non-Hispanic (59.7%) and female (60.4%). Approximately one quarter of individuals (27.0%) worked in the manufacturing industry (e.g. fabricated metal product manufacturing, medical equipment and supplies manufacturing, and perishable prepared food manufacturing) and nearly one fifth of individuals (19.2%) worked in a production occupation (e.g. engine and other machine assemblers, bakers, cabinet makers) when their work-related asthma began.

Table 1.

Select characteristics of work-related asthma by gender — California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey, 1993–2008.

| Total | Females | Males | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % | p Valuea |

| Total | 8237 | 100.0 | 4973 | 100.0 | 3264 | 100.0 | |

| State | |||||||

| California | 4638 | 56.3 | 2945 | 59.2 | 1693 | 51.9 | <0.0001 |

| Massachusetts | 787 | 9.6 | 502 | 10.1 | 285 | 8.7 | 0.0396 |

| Michigan | 2341 | 28.4 | 1265 | 25.4 | 1076 | 33.0 | <0.0001 |

| New Jersey | 471 | 5.7 | 261 | 5.3 | 210 | 6.4 | 0.023 |

| Reporting Source | |||||||

| Healthcare professional report | 5788 | 70.3 | 3470 | 69.8 | 2318 | 71.0 | 0.228 |

| Hospital datab | 1257 | 15.3 | 706 | 14.2 | 551 | 16.9 | 0.001 |

| Workers’ compensation | 1083 | 13.2 | 738 | 14.8 | 345 | 10.6 | <0.0001 |

| Co-worker | 17 | 0.2 | 11 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.2 | 0.715 |

| Poison control centers | 66 | 0.8 | 37 | 0.7 | 29 | 0.9 | 0.472 |

| Otherc | 26 | 0.3 | 11 | 0.2 | 15 | 0.5 | 0.059 |

| Work-Related Asthma Classification | |||||||

| Work-aggravated asthmad | 1654 | 20.1 | 1213 | 24.4 | 441 | 13.5 | <0.0001 |

| New-onset asthmae | 4229 | 51.3 | 2386 | 48.0 | 1843 | 56.5 | <0.0001 |

| Occupational asthma | 3620 | 43.9 | 2061 | 41.5 | 1559 | 47.8 | 0.002 |

| Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (RADS) | 609 | 7.4 | 325 | 6.5 | 284 | 8.7 | 0.004 |

| Confirmed, but unclassifiablef | 2354 | 28.6 | 1374 | 27.6 | 980 | 30.0 | 0.467 |

| Age | |||||||

| 16–24 | 670 | 8.1 | 311 | 6.3 | 359 | 11.0 | <0.0001 |

| 25–34 | 1572 | 19.1 | 850 | 17.1 | 722 | 22.1 | <0.0001 |

| 35–44 | 2369 | 28.8 | 1467 | 29.5 | 902 | 27.6 | 0.068 |

| 45–54 | 2329 | 28.3 | 1537 | 30.9 | 792 | 24.3 | <0.0001 |

| 55–64 | 1130 | 13.7 | 712 | 14.3 | 418 | 12.8 | 0.051 |

| ≥65 | 111 | 1.4 | 65 | 1.3 | 46 | 1.4 | 0.694 |

| Unknown | 56 | 0.7 | 31 | 0.6 | 25 | 0.8 | 0.441 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 4008 | 48.7 | 2410 | 48.5 | 1598 | 49.0 | 0.659 |

| Black | 864 | 10.5 | 594 | 11.9 | 270 | 8.3 | <0.0001 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 104 | 1.3 | 62 | 1.3 | 42 | 1.3 | 0.874 |

| Asian | 160 | 1.9 | 112 | 2.3 | 48 | 1.5 | 0.012 |

| Other/mixed race | 388 | 4.7 | 235 | 4.7 | 153 | 4.7 | 0.937 |

| Unknown | 2713 | 32.9 | 1560 | 31.4 | 1153 | 35.3 | 0.0002 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 602 | 7.8 | 349 | 7.5 | 253 | 8.2 | 0.223 |

| Non-Hispanic | 4635 | 59.7 | 2915 | 62.2 | 1720 | 55.8 | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 2530 | 32.6 | 1420 | 30.3 | 1110 | 36.0 | <0.0001 |

| Major Industry (NAICS 2002) | |||||||

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing (11) | 156 | 1.9 | 49 | 1.0 | 107 | 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Mining (21) | 14 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.3 | 0.015 |

| Utilities (22) | 84 | 1.0 | 40 | 0.8 | 44 | 1.4 | 0.016 |

| Construction (23) | 275 | 3.3 | 37 | 0.7 | 238 | 7.3 | <0.0001 |

| Manufacturing (31–33) | 2222 | 27.0 | 955 | 19.2 | 1267 | 38.8 | <0.0001 |

| Wholesale trade (42) | 134 | 1.6 | 57 | 1.2 | 77 | 2.4 | <0.0001 |

| Retail trade (44–45) | 374 | 4.6 | 247 | 5.0 | 127 | 3.9 | 0.022 |

| Transportation and warehousing (48–49) | 297 | 3.6 | 137 | 2.8 | 160 | 4.9 | <0.0001 |

| Information (51) | 146 | 1.8 | 112 | 2.3 | 34 | 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| Finance and insurance (52) | 140 | 1.7 | 126 | 2.5 | 14 | 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Real estate, rental, and leasing (53) | 59 | 0.7 | 31 | 0.6 | 28 | 0.9 | 0.217 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services (54) | 159 | 1.9 | 113 | 2.3 | 46 | 1.4 | 0.005 |

| Management of companies and enterprises (55) | 2 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.522 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services (56) | 255 | 3.1 | 117 | 2.4 | 138 | 4.2 | <0.0001 |

| Educational services (61) | 723 | 8.8 | 586 | 11.8 | 137 | 4.2 | <0.0001 |

| Healthcare and social assistance (62) | 1597 | 19.4 | 1427 | 28.7 | 170 | 5.2 | <0.0001 |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation (71) | 117 | 1.4 | 70 | 1.4 | 47 | 1.4 | 0.903 |

| Accommodation and food services (72) | 206 | 2.5 | 136 | 2.7 | 70 | 2.1 | 0.093 |

| Other services (except public administration) (81) | 181 | 2.2 | 91 | 1.8 | 90 | 2.8 | 0.005 |

| Public administration (92) | 882 | 10.7 | 527 | 10.6 | 355 | 10.9 | 0.689 |

| Unknown | 214 | 2.6 | 109 | 2.2 | 105 | 3.2 | 0.004 |

| Major Occupation (COC 2000) | |||||||

| Management (001–043) | 253 | 3.1 | 189 | 3.8 | 64 | 2.0 | <0.0001 |

| Business and financial operations (050–095) | 121 | 1.5 | 108 | 2.2 | 13 | 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Computer and mathematical (100–124) | 56 | 0.7 | 40 | 0.8 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.090 |

| Architecture and engineering (130–156) | 76 | 0.9 | 28 | 0.6 | 48 | 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Life, physical and social services (160–196) | 135 | 1.6 | 91 | 1.8 | 44 | 1.4 | 0.092 |

| Community and social services (200–206) | 105 | 1.3 | 88 | 1.8 | 17 | 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Legal (210–215) | 20 | 0.2 | 17 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.024 |

| Education training and library (220–255) | 349 | 4.2 | 307 | 6.2 | 42 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media (260–296) | 29 | 0.4 | 18 | 0.4 | 11 | 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| Healthcare practitioners and technical (300–354) | 719 | 8.7 | 668 | 13.4 | 51 | 1.6 | <0.0001 |

| Healthcare support (360–365) | 271 | 3.3 | 250 | 5.0 | 21 | 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Protective service (370–395) | 410 | 5.0 | 147 | 3.0 | 263 | 8.1 | <0.0001 |

| Food preparation and serving related (400–416) | 177 | 2.2 | 121 | 2.4 | 56 | 1.7 | 0.028 |

| Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance (420–425) | 428 | 5.2 | 220 | 4.4 | 208 | 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| Personal care and service (430–465) | 111 | 1.4 | 94 | 1.9 | 17 | 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Sales and related (470–496) | 219 | 2.7 | 165 | 3.3 | 54 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| Office and administrative support (500–593) | 1122 | 13.6 | 993 | 20.0 | 129 | 4.0 | <0.0001 |

| Farming, fishing, and forestry (600–613) | 81 | 1.0 | 32 | 0.6 | 49 | 1.5 | 0.0001 |

| Construction and extraction (620–694) | 331 | 4.0 | 34 | 0.7 | 297 | 9.1 | <0.0001 |

| Installation repair and maintenance (700–762) | 246 | 3.0 | 31 | 0.6 | 215 | 6.6 | <0.0001 |

| Production (770–896) | 1585 | 19.2 | 679 | 13.7 | 906 | 27.8 | <0.0001 |

| Transportation and material moving (900–975) | 564 | 6.9 | 205 | 4.1 | 359 | 11.0 | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 829 | 10.1 | 448 | 9.0 | 381 | 11.7 | <0.0001 |

COC, Census Occupation Classification; NAICS, North American Industrial Classification System (The numbers in parentheses signify NAICS 2002 codes or COC 2000 codes).

p Value for gender differences.

Includes hospital discharge and emergency department data.

Cases identified through death certificates, self-report, reports from the Mine Safety and Health Administration, and reports from Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Pre-existing asthma aggravated by exposure or condition at work.

Includes cases of reactive airways dysfunction syndrome and occupational asthma.

Confirmed cases of work-related asthma that lack the necessary information to determine if they are new-onset asthma or work-aggravated asthma.

Numbers may not add up to total because of missing values.

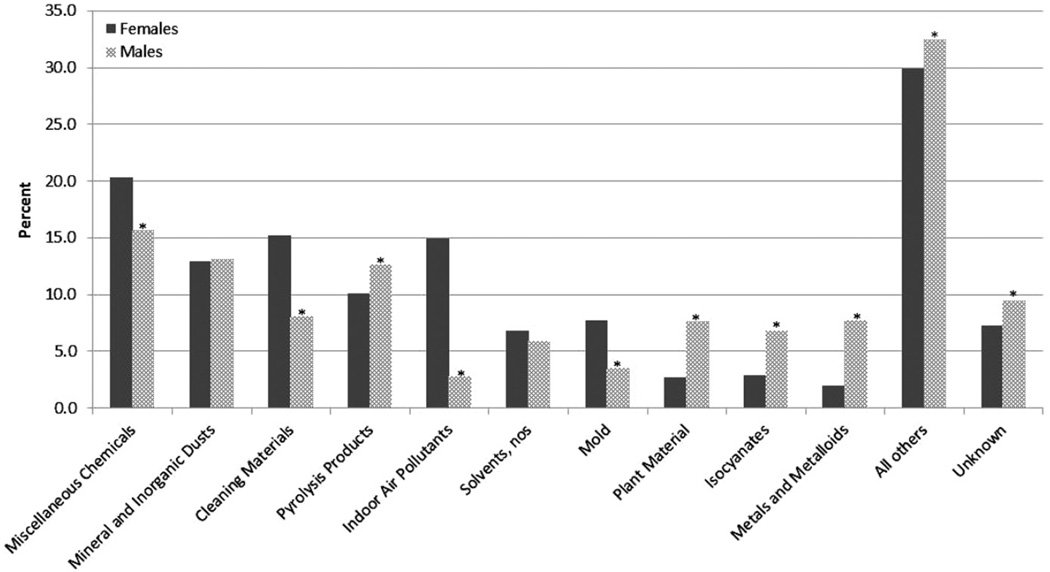

The most frequently reported AOEC agent categories and the most frequent individual agents within each category are shown in Table 2. A total of 10 722 putative agents associated with work-related asthma were reported; 5097 (61.9% of 8237) individuals reported only one agent, 1778 (21.6% of 8237) individuals reported two agents, 694 (8.4% of 8237) individuals reported three agents, and for 670 (8.1%) individuals agents were not known. The three most common reported agent categories were miscellaneous chemicals (18.5%), mineral and inorganic dusts (13.0%), and cleaning materials (12.5%) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Ten most frequent major AOEC agent categories reported and examples by gender.

| Category | Total | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miscellaneous Chemicals | |||

| Chemicals, NOS | Chemicals, NOS | Chemicals, NOS | |

| Perfume, NOS | Perfume, NOS | Pesticides, NOS | |

| Glues, NOS | Glues, NOS | Glues, NOS | |

| Pesticides, NOS | Pesticides, NOS | Fire extinguisher discharge | |

| Odors | Odors | Printing chemicals, NOS | |

| Cleaning Materials | |||

| Cleaning materials, NOS | Cleaning materials, NOS | Cleaning materials, NOS | |

| Bleach | Bleach | Bleach | |

| Floor stripping cleaners | Floor stripping cleaners | Ammonium hydroxide, NOS | |

| Cleaners, disinfectants, NOS | Cleaners, disinfectants, NOS | Floor stripping cleaners | |

| Carpet cleaners | Carpet cleaners | Cleaning mixtures (excluding bleach plus acid or ammonia) | |

| Mineral and Inorganic Dusts | |||

| Dust, NOS | Dust, NOS | Dust, NOS | |

| Man-made mineral fibers, NOS | Man-made mineral fibers, NOS | Man-made mineral fibers, NOS | |

| Asbestos, NOS | Asbestos, NOS | Cement dust | |

| Cement dust | Carbon black | Asbestos, NOS | |

| Silica, crystalline, NOS | Cement dust | Silica, crystalline, NOS | |

| Pyrolysis products | |||

| Smoke, NOS | Smoke, NOS | Smoke, NOS | |

| Diesel Exhaust | Cigarette smoke | Diesel exhaust | |

| Cigarette smoke | Diesel exhaust | Plastic smoke | |

| Plastic smoke | Plastic smoke | Exhaust, NOS | |

| Exhaust, NOS | Exhaust, NOS | Cigarette smoke | |

| Indoor air pollutants | |||

| Air pollutants, indoor | Air pollutants, indoor | Air pollutants, indoor | |

| Indoor air pollutants from building | Indoor air pollutants from building | Indoor air pollutants from building | |

| Solvents, NOS | |||

| Paint, NOS | Paint, NOS | Paint, NOS | |

| Solvents, NOS | Solvents, NOS | Solvents, NOS | |

| Paint, oil-based | Paint, oil-based | Paint, oil-based | |

| Thinner | Thinner | Thinner | |

| Lacquer | Lacquer | Lacquer | |

| Mold | |||

| Mold, NOS | Mold, NOS | Mold, NOS | |

| Aspergillus | Aspergillus | Aspergillus | |

| Stachybotrys | Stachybotrys | Stachybotrys | |

| Pennicillium | Pennicillium | Pennicillium | |

| Plant material | |||

| Plant material, NOS | Capsicum | Wood dust, NOS | |

| Wood dust, NOS | Plant material, NOS | Plant material, NOS | |

| Capsicum | Wood dust, NOS | Flour, NOS | |

| Flour, NOS | Paper dust | Pollen | |

| Paper dust | Pollen | Paper dust | |

| Isocyanates | |||

| Diisocyanates, NOS | Diisocyanates, NOS | Diisocyanates, NOS | |

| Toluene diisocyanate | Toluene diisocyanate | Methylene bisphenyl diisocyanate | |

| Methylene bisphenyl diisocyanate | Methylene bisphenyl diisocyanate | Toluene diisocyanate | |

| Hexamethylene diisocyanate | Hexamethylene diisocyanate | Hexamethylene diisocyanate | |

| Naphthalene diisocyanate | Naphthalene diisocyanate | Naphthalene diisocyanate | |

| Metals and metalloids | |||

| Welding, NOS | Welding, NOS | Welding, NOS | |

| Metal dust, NOS | Soldering flux, NOS | Metal dust, NOS | |

| Cobalt compounds | Soldering, NOS | Cobalt compounds | |

| Welding fumes, stainless steel | Cobalt compounds | Welding fumes, stainless steel | |

| Nickel compounds | Welding fumes, stainless steel | Soluble halogenated platinum compounds, NOS | |

AOEC, Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics. NOS, not otherwise specified.

AOEC exposure categories as of September, 2012. See AOEC exposure code lookup (http://www.aoecdata.org/) for more information.

Figure 1.

Major AOEC agent categories for reported exposures associated with work-related asthma by gender—California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey, 1993–2008. AOEC, Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics. *p Value for gender differences <0.05. AOEC exposure categories as of September, 2012. See AOEC exposure code lookup (http://www.aoecdata.org/) for more information. Each case may be associated with up to three putative agents. A total of 10 722 putative agents associated with work-related asthma were reported. In 670 cases (8.1%) agents were not identified. Percentages are based on the number of females (4973) and males (3264). All other major AOEC exposure categories include aldehydes and acetals; aromatic hydrocarbons; animal materials; ergonomics; miscellaneous inorganic compounds; halogens (inorganic); physical factors; epoxy compounds; hydrocarbons, not otherwise specified; polymers; acids, bases, and oxidizing agents; aliphatic and alicyclic hydrocarbons; esters; halogenated aliphatic hydrocarbons; ketones; aliphatic and alicyclic amines; alcohols; aliphatic and miscellaneous nitrogen compounds; organophosphate pesticides/carbamate pesticides; phenols and phenolic compounds; glycol ethers; microorganisms, not including mold; glycols; organic sulfur compounds; aliphatic carboxylic acids; cyanides and nitriles; ethers; halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons; aromatic nitro and amino compounds; organochlorine insecticides.

When compared to males, significantly higher proportions of females were ascertained through workers’ compensation (14.8% versus 10.6%), had work-aggravated asthma (24.4% versus 13.5%), were 45–54 years old (30.9% versus 24.3%), black (11.9% versus 8.3%), Asian (2.3% versus 1.5%), and non-Hispanic (62.2% versus 55.8%) (Table 1). Significantly lower proportions of females were ascertained through hospital data (14.2% versus 16.9%), had new-onset asthma (48.0% versus 56.5%), and were 16–24 years old (6.3% versus 11.0%) and 25–34 years old (17.1% versus 22.1%) when compared to males.

Females also differed from males in the industries and occupations they worked in when their work-related asthma began. By industry, when compared to males, significantly higher proportions of females worked in healthcare and social assistance (28.7% versus 5.2%), educational services (11.8% versus 4.2%), and retail trade (5.0% versus 3.9%) industries and significantly lower proportions worked in manufacturing (19.2% versus 38.8%), transportation and warehousing (2.8% versus 4.9%), construction (0.7% versus 7.3%), administrative support and waste management (2.4% versus 4.2%), and other services (except public administration) (1.8% versus 2.8%) industries. By occupation, when compared to males, significantly higher proportions of females worked in office and administrative support (20.0% versus 4.0%), healthcare practitioners and technical (13.4% versus 1.6%), education training and library (6.2% versus 1.3%), healthcare support (5.0% versus 0.6%), and management (3.8% versus 2.0%) occupations and significantly lower proportions worked in production (13.7% versus 27.8%), transportation and material moving (4.1% versus 11.0%), building and grounds cleaning and maintenance (4.4% versus 6.4%), protective service (3.0% versus 8.1%), and construction and extraction (0.7% versus 9.1%) occupations (Table 1). Within industries, occupations associated with work-related asthma differed by gender (Table 3). For example, within the construction industry, females were more likely to work in office and administrative support occupations (21.6% versus 0.4%) and less likely to work in construction and extraction occupations (27.0% versus 68.1%) than males. In addition, within the educational services industry, females were more likely to work in education, training and library occupations (47.4% versus 26.3%) and less likely to work in building and grounds, cleaning, and maintenance occupations (6.7% versus 38.7%) than males. Examples of occupations within each industry group are shown in Appendix 1.

Table 3.

Occupation distribution among industry groups for females and males with work-related asthma — California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey, 1993–2008.

| Top Ten Major Occupation Groups (COC 2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Ten Major Industry Groups (NAICS 2002) |

Production (770–896) % |

Office and administrative support (500–593) % |

Healthcare practitioners and technical (300–354) % |

Transportation and material moving (900–975) % |

Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance (420–425) % |

Protective service (370–395) % |

Education training and library (220–255) % |

Construction and extraction (620–694) % |

Healthcare support (360–365) % |

Management (001–043) % |

All other major occupation categoriesa % |

Unknown % |

|

| Manufacturing (31–33) n = 2222 | F | 62.6b | 7.3b | 0.6b | 9.6 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5b | 0 | 1.8 | 8.3b | 6.9 |

| M | 58.4 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 10.1 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 4.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 12.2 | 9.2 | |

| Healthcare and social assistance (62) n = 1597 | F | 0.8b | 17.9b | 42.1b | 0.1 | 3.9b | 0.5b | 0.6 | 0.9b | 15.6b | 2.8 | 8.9b | 6.0 |

| M | 4.1 | 3.5 | 25.3 | 1.2 | 12.9 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 15.3 | 7.1 | |

| Public administration (92) n = 882 | F | 1.1b | 39.9b | 3.8b | 1.1b | 1.0b | 18.4b | 1.5 | 0.2b | 1.0b | 5.5b | 17.1b | 9.5 |

| M | 3.4 | 6.5 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 53.2 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 10.4 | 9.6 | |

| Educational services (61) n = 723 | F | 0.2 | 13.5b | 3.2 | 1.2 | 6.7b | 0.7b | 47.4b | 0.2b | 1.0 | 4.6 | 14.5 | 6.8 |

| M | 0.7 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 38.7 | 5.1 | 26.3 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 2.9 | 9.5 | 7.3 | |

| Retail trade (44–45) n = 374 | F | 4.5 | 16.2b | 1.2 | 9.7 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 0 | 0b | 0.4 | 0.4 | 51.8b | 12.6 |

| M | 7.1 | 8.7 | 0.8 | 14.2 | 6.3 | 1.6 | 0 | 3.9 | 0 | 0 | 39.4 | 18.1 | |

| Transportation and warehousing (48–49) n = 297 | F | 1.5 | 27.7b | 1.5 | 33.6b | 2.9 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 16.1 | 10.2 |

| M | 4.4 | 10.0 | 0 | 60.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0 | 10.6 | 9.4 | |

| Construction (23) n = 275 | F | 8.1 | 21.6b | 0 | 8.1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 27.0b | 0 | 2.7 | 16.2 | 13.5 |

| M | 8.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 4.2 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 68.1 | 0 | 1.7 | 9.2 | 5.9 | |

| Administrative and support, waste, management and remediation services (56) n = 255 | F | 9.4 | 25.6b | 0.9 | 5.1b | 23.9 | 9.4 | 0 | 0b | 0 | 3.4 | 10.3 | 12.0 |

| M | 14.5 | 5.1 | 0 | 21.7 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 0 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.7 | 10.1 | 14.5 | |

| Accommodation and food services (72) n = 206 | F | 1.5 | 8.1b | 0 | 1.5 | 25.7b | 0.7 | 0 | 0b | 0 | 9.6 | 47.1 | 5.9 |

| M | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 12.9 | 1.4 | 0 | 4.3 | 0 | 7.1 | 58.6 | 8.6 | |

| Other services (except public administration) (81) n = 181 | F | 11.0b | 26.4b | 0 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 0 | 1.1 | 0b | 2.2 | 1.1b | 44.0 | 8.8 |

| M | 28.9 | 0 | 0 | 4.4 | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 5.6 | 0 | 7.8 | 38.9 | 6.7 | |

| All other major industry categoriesc n = 1011 | F | 3.2b | 36.3b | 2.2b | 1.8b | 3.3b | 3.8b | 1.3b | 0.7b | 1.5 | 8.6 | 28.3 | 9.1b |

| M | 12.0 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 11.3 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 0 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 5.4 | 31.0 | 13.8 | |

| Unknown n = 214 | F | 4.6 | 7.3b | 2.8 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0b | 0 | 0.9 | 8.3 | 66.1 |

| M | 10.5 | 1.0 | 0 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 | 65.7 | |

COC, Census Occupation Codes; F, females; M, males; NAICS, North American Industrial Classification System (The numbers in parentheses signify NAICS 2002 codes or COC 2000 codes); Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

All other major occupation categories include business and financial operations (050–095); computer and mathematical (100–124); architecture and engineering (130–156); life, physical, and social services (160–196); community and social services (200–206); legal (210–215); arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media (260–296); food preparation and serving related (400–416); personal care and service (430–465); sales and related (470–496); farming, forestry, and fishing (600–613); installation, repair, and maintenance (700–762); military, rank not specified (983).

p Value for gender differences <0.05.

All other major industry categories include agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (11); mining (21); utilities (22); wholesale trade (42); information (51); finance and insurance (52); real estate and rental and leasing (53); professional, scientific, and technical services (54); management of companies and enterprises (55); arts, entertainment, and recreation (71).

Females and males also significantly differed in the exposures associated with their work-related asthma. Females were significantly more likely than males to have reported exposure to miscellaneous chemicals (20.3% versus 15.7%), cleaning materials (15.3% versus 8.2%), indoor air pollutants (14.9% versus 2.8%), and mold (7.8% versus 3.6%) (Figure 1). Females were significantly less likely than males to report pyrolysis products (10.1% versus 12.7%), plant materials (2.7% versus 7.7%), isocyanates (2.9% versus 6.9%), and metals and metalloids (2.0% versus 7.8%) (Figure 1).

Discussion

In this study of individuals with confirmed work-related asthma from four state-based sentinel surveillance programs, approximately 60% were female. These findings are similar to findings from Washington State where 57.1% of individuals with work-related asthma were females [22] and slightly higher than findings from the New York State Occupational Health Clinic Network where 53.7% of individuals with work-related asthma were females [23]. Moreover, these findings are consistent with 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey findings from these four states that an estimated 62.9%–65.3% of adults with current asthma are females [24]. Additionally, data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey indicate that the proportion of asthma that is diagnosed as work-related asthma by a healthcare professional does not significantly differ by gender [25,26]. Accordingly, the proportion of individuals with work-related asthma that are female may reflect the gender distribution in adult asthma.

Multiple reasons have been hypothesized why among adults with asthma females make up a higher proportion than males. First, sex hormones may influence biological differences in pulmonary and immunological factors associated with asthma [27]. Furthermore, the diagnosis of asthma depends both on the diagnostic practices of healthcare professionals and the healthcare seeking behavior of individuals, particularly those with milder forms of asthma (presumably individuals with more severe asthma have less discretion on whether or not to seek medical care). For example, Schatz and Camargo have reported that females are more likely to have outpatient visits for their asthma than males [28]. Additionally, females with asthma describe more symptoms than males with asthma despite having better or comparable pulmonary function [29,30]. Also, studies 25–30 years ago, found that among adults with similar respiratory symptoms and smoking status, females were more likely to be diagnosed with asthma and chronic bronchitis while males were more likely to be diagnosed with emphysema, suggesting physician bias in diagnostic practices during that time period [31].

In addition to possible gender differences in asthma identification, a review article by Camp et al. suggests that a number of other factors may lead to gender differences in the development of occupational lung diseases including work-related asthma [32]. First, even though males and females may have the same job title, they can have different job tasks that lead to variation in types and levels of exposure. For example, male cleaners may be assigned to mopping floors while female cleaners are assigned to clean toilets [32,33]. Second, in workplaces in which respirators are worn, but fit testing is not done (as required when necessary to prevent overexposure, by OSHA 1910.134 Respiratory Protection Standard), respirators may not fit females’ faces, which may lead to increased exposure in females [32,34]. Third, structural differences in adult male and female lungs such as lung size, airway caliber, vital capacity, and expiratory flow rates may impact the volume of inhaled agent per breath and the deposition of the inhaled agent in the lung [32,35].

We found that among individuals with work-related asthma, females were more likely to have work-aggravated asthma and less likely to have new-onset asthma than males. Our findings are consistent with findings from surveillance systems in the United Kingdom [36,37], Canada [38], and France [39] that found that males had more new-onset asthma than females. Lemiere and colleagues found that among adults in an asthma tertiary care center in Quebec, both subjects with work-aggravated-asthma and those with work-related new-onset asthma were less likely to be in females (43% and 34%, respectively) compared to subjects with non-work-related asthma among whom 58% were females [40]. In addition, in a study of health maintenance organization members with asthma in Massachusetts, Henneberger and colleagues found that those with workplace exacerbation of asthma were less likely to be females than those without workplace exacerbation of asthma (55% versus 73%, respectively) [41]. This differs from our findings where 73.3% of individuals with work-aggravated asthma, 56.4% of individuals with work-related new-onset asthma, and 58.4% of individuals with confirmed but unclassified work-related asthma were female (data not shown). The differences may be explained by differences in study populations and methods.

Data from a French voluntary reporting system of occupational and chest physicians has shown that the occupations associated with new-onset asthma differ by gender [39]. Consistent with our results, Ameille and colleagues found that females with new-onset asthma were more likely than males to be healthcare workers when their asthma started (26.4% versus 1.1%, respectively) [39]. We also found that occupations differed by gender within all major industries for individuals with work-related asthma. This is consistent with a 2013 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on women in the labor force which indicates that the share of females working in specific occupations varies largely within the United States. For example, females account for 98% of preschool and kindergarten teachers, 74% of cashiers, 43% of bus drivers and 2% of carpenters. Similarly, the proportion of females working in specific industries varies largely within the United States. For example, females account for 79% of workers in the health care and social assistance industry, 49% of workers in the retail trade industry, 25% of workers in the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industry, and 9% of workers in the construction industry [42].

The reported exposures associated with work-related asthma also differed by gender. In this study of individuals with work-related asthma, females were significantly more likely than males to report that miscellaneous chemicals, cleaning materials, indoor air pollutants, and mold were associated with their work-related asthma. Dimich-Ward et al. found that the risk of asthma and asthma symptoms by gender differed based on the type of occupational exposure (organic/inorganic dusts) and on industry and occupation of the worker [43]. The authors found that males exposed to organic dusts in their jobs had greater risk of asthma symptoms than female coworkers. Among workers exposed to inorganic dusts, the risk of asthma was higher for females than males. The results by Dimich-Ward et al. suggest that the associations between gender, occupation, exposure, and work-related asthma are complex and need to be explored [43].

The strengths and limitations of the state-based sentinel surveillance data have been described elsewhere [4]. Due to under-recognition and under-reporting of work-related asthma by healthcare professionals, the findings from the state-based sentinel surveillance systems are not necessarily representative of the underlying burden of work-related asthma. Asthma-like symptoms in patients might be inadequately diagnosed or the connection between asthma symptoms and the workplace may not be made. In Michigan, it has been reported that only 1.3% of physicians report cases to the state-based sentinel surveillance system [44]. However, even with under-reporting, the state-based sentinel surveillance system for work-related asthma has the ability to capture in-depth industry, occupation, and workplace exposure information. We were unable to draw any conclusions regarding whether the gender differences in industry and occupation in this population of individuals with work-related asthma reflected gender differences in industry and occupation in the general populations in these four states. Factors such as gender differences in asthma prevalence, access to medical care, medical care seeking behaviors, and reporting of work-related asthma to state health departments may all impact the ascertainment of work-related asthma cases by state health departments. Future studies should examine gender differences in the incidence of work-related asthma. Information presented here is limited to four states with sentinel work-related asthma surveillance capabilities. These four states have very different industry and occupation profiles and are not necessarily representative of other states or the entire country.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study done in the United States that describes industries, occupations, and workplace exposures associated with work-related asthma by gender. While we cannot establish that work is responsible for the higher prevalence of asthma among females, our study adds to the increasing evidence that work impacts females with asthma and that gender differences impact work-related asthma. Gender differences in workplace exposures, occupations, and industries of workers may contribute to differential risk of work-related asthma. Healthcare professionals should be cognizant that unlike the classic occupational lung diseases such as asbestosis and silicosis, which are more common in males, work-related asthma is more commonly identified in females. Moreover, healthcare professionals need to consider gender differences in workplace exposure, occupations, and industries when diagnosing and treating adults with asthma.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karen R. Cummings, New York State Department of Health and Jeanne E. Moorman, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their helpful comments.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Funding to support this project was provided through cooperative agreements from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health U60-OH-008468 (California), U60-OH-008490 (Massachusetts), U60-OH-008466 (Michigan), and U60-OH0008485 (New Jersey).

Appendix 1

Examples of industry and occupation combinations among adults with work-related asthma — California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey, 1993–2008.

| Top Ten Major Occupation Groups (COC 2000) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Ten Major Industry Groups (NAICS 2002) | Production (770–896) | Office and administrative support (500–593) | Healthcare practitioners and technical (300–354) | Transportation and material moving (900–975) | Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance (420–425) | Protective service (370–395) | Education training and library (220–255) | Construction and extraction (620–694) | Healthcare support (360–365) | Management (001–043) | All other major occupation categoriesa |

| Manufacturing (31–33) n = 2,222 | Motor vehicle parts manufacturing (336 300) | Motor vehicle parts manufacturing (336 300) | Spring manufacturing (332 612) | Motor vehicle parts manufacturing (336 300) | Motor vehicle parts manufacturing (336 300) | Chemical manufacturing 325 000 | Semiconductor and related device manufacturing 334 413 | Motor vehicle parts manufacturing (336 300) | Pharmaceutical preparation manufacturing 325 412 | Guided missile and space vehicle manufacturing 336 414 | Pharmaceutical preparation manufacturing 325 412 |

| Miscellaneous assemblers and fabricators (775) | Shipping receiving and traffic clerk (561) | Registered nurse (313) | Hand packers and packagers (963) | Janitors and building cleaners (422) | Security guards and gaming surveillance officer (392) | Other teachers and instructors (234) | Pipelayers, plumbers, pipefitters, and steamfitters (644) | Medical assistant and other healthcare support (365) | Managers (043) | Chemical technician (192) | |

| Healthcare and social assistance (62) n = 1,597 | Nursing care facilities (623 110) | Medical and surgical hospitals (622 110) | Ambulatory health care services (621 000) | Ambulance services (621 910) | Medical and surgical hospitals (622 110) | Vocational rehabilitation services (624 310) | Child day care services (624 410) | Vocational rehabilitation services (624 310) | Medical and surgical hospitals (622 110) | Medical and surgical hospitals (622 110) | Other individual and family services (624 190) |

| Laundry worker (830) | Secretaries and administrative (570) | Registered nurse (313) | Taxi drivers and chauffeurs (914) | Janitors and building cleaners (422) | Fire fighter (374) | Preschool and kindergarten teachers (230) | Construction laborer (626) | Medical assistant and other healthcare support (365) | Medical and health services managers (035) | Social worker (201) | |

| Public administration (92) n = 882 | Administration of air and water resource and solid waste management programs (924 110) | Public finance activities (921 130) | Administration of public health programs (923 120) | Regulation and administration of transportation program (926 120) | Other general government support (921 190) | Fire protection (922 160) | Correctional institutions (922 140) | National security (928 110) | Correctional institutions (922 140) | Other general government support (921 190) | Legislative bodies (922 120) |

| Water and liquid waste treatment plant and systems operator (862) | Office clerk (586) | Registered nurse (313) | Bus driver (912) | Janitors and building cleaners (422) | Fire fighter (374) | Other teachers and instructors (234) | Electrician (635) | Dental assistant (364) | Managers (043) | Other life, physical and social science technicians (196) | |

| Educational services (61) n = 723 | Junior colleges (611 210) | Colleges, universities, and professional schools (611 310) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) | Colleges, universities, and professional schools (611 310) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) | Colleges, universities, and professional schools (611 310) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) | Elementary and secondary schools (611 110) |

| Photographic process workers and processing machine operators (883) | Secretaries and administrative (570) | Registered nurse (313) | Bus driver (912) | Janitors and building cleaners (422) | Police and sheriff’s patrol officers (385) | Elementary and middle school teachers (231) | Painters, construction and maintenance (642) | Nursing psychiatric and home health aides (360) | Education administrators (023) | Child care workers (460) | |

| Retail trade (44–45) n = 374 | Supermarkets and other grocery stores (445 110) | Supermarkets and other grocery stores (445 110) | Pharmacies and drug stores (446 110) | Supermarkets and other grocery stores (445 110) | Supermarkets and other grocery stores (445 110) | Department stores (452 111) | Home centers (444 110) | Pharmacies and drug stores (446 110) | Specialty food stores (445 200) | Furniture stores (442 110) | |

| Butchers and other meat poultry and fish processing workers (781) | Stock clerks and order fillers (562) | Emergency medical technicians and paramedics (340) | Laborers and freight stock and material movers (962) | Janitors and building cleaners (422) | Security guards and gaming surveillance officer (392) | Construction laborers (626) | Medical assistant and other healthcare support (365) | Property real estate and community association managers (041) | Retail salesperson (476) | ||

| Transportation and warehousing (48–49) n = 297 | Other warehousing and storage (493 190) | Postal services (491 110) | Other nonscheduled air transportation (481 219) | Urban transit systems (485 110) | Support activities for transportation (488 000) | Motor vehicle towing (488 410) | Freight transportation arrangement (488 510) | All other transit and ground passenger transportation (485 999) | General warehousing and storage (493 110) | Urban transit systems (485 110) | |

| Extruding forming pressing and compacting machine setters, operators, and tenders (874) | Postal service mail sorters, processors, and processing machine operators (556) | Miscellaneous health technologists and technicians (353) | Bus driver (912) | First line supervisors/managers of housekeeping and janitorial workers (420) | Private detectives and investigators (391) | Sheet metal workers (652) | Nursing psychiatric and home health aides (360) | Lodging manager (034) | Bus and truck mechanics and diesel engine specialists (721) | ||

| Construction (23) n = 275 | Other specialty trade contractors (238 990) | Highway street and bridge construction (237 310) | Painting and wall covering contractors (238 320) | Highway street and bridge construction (237 310) | Highway street and bridge construction (237 310) | Masonry contractor (238 140) | Plumbing heating and air-conditioning contractor (238 220) | ||||

| Welding, soldering, and brazing workers (814) | Secretaries and administrative (570) | Material moving workers (975) | Grounds maintenance workers (425) | Construction laborers (626) | Construction manager (022) | Heating air-air conditioning and refrigeration mechanics and installers (731) | |||||

| Administrative and support, waste, management and remediation services (56) n = 255 | Carpet and upholstery cleaning services (561 740) | Administrative and support services (561 000) | Employment placement agencies (561 310) | Solid waste collection (562 111) | Janitorial services (561 720) | Investigation, guard, and armored car service (561 610) | Employment placement agencies (561 310) | All other business support services (561 499) | Administrative and support services (561 000) | ||

| Laundry worker (830) | Office clerk (586 | Registered nurse (313) | Driver/sales workers and truck drivers (913) | First line supervisors/managers of housekeeping and janitorial workers (420) | Security guards and gaming surveillance officer (392) | Construction laborers (626) | Marketing and sales managers (005) | Other life physical and social science technicians (196) | |||

| Accommodation and food services (72) n = 206 | Food services and drinking places (722 000) | Hotels (except casino hotels) and motels (721 110) | Hotels (except casino hotels) and motels (721 110) | Hotels (except casino hotels) and motels (721 110) | Travel accommodation (721 100) | Hotels (except casino hotels) and motels (721 110) | Full service restaurant (7221 10) | Full service restaurant (722 110) | |||

| Bakers (780) | Hotel motel and resort desk clerks (530) | Service station attendants (936) | Maids and housekeeping cleaners (423) | Lifeguards and other protective service worker (395) | Painters construction and maintenance (642) | Food service managers (031) | Food preparation and serving related workers (416) | ||||

| Other services (except public administration) (81) n = 181 | Photofinishing (812 920) | Religious organizations (813 110) | All other automotive repair and maintenance (811 198) | Private households (814 110) | Beauty salons (812 112) | Labor unions and similar labor organizations (813 930) | Other personal care services (812 199) | General automotive repair (811 111) | Beauty salons (812 112) | ||

| Production workers, all others (896) | Secretaries and administrative assistants (570) | Driver/sales workers and truck drivers (913) | Maids and housekeeping cleaners (423) | Other teachers and instructors (234) | Brickmasons, block-masons, and stonemasons (622) | Massage therapist (363) | Managers (043) | Hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists (451) | |||

| All other major industry categoriesb n = 1,011 | Other electric power generation (221 119) | Electric power distribution (221 122) | Medical, dental, and hospital equipment and supplies merchant wholesalers (423 450) | Wholesale trade (420 000) | Lessors of residential buildings and dwellings (531 110) | Fitness and recreational sports center (713 940) | Libraries and archives (519 120) | Lessors of residential buildings and dwellings (531 110) | Research and development in physical engineering and life sciences (541 710) | Dairy cattle and milk production (112 120) | Grape vineyards (111 332) |

| Power plant operators distributors and dispatchers (860) | Customer service representatives (524) | Registered nurse (313) | Laborers and freight stock and material movers (962) | First line supervisors/managers of housekeeping and janitorial workers (420) | Lifeguards and other protective service worker (395) | Librarians (243) | Painters construction and maintenance (642) | Medical assistant and other healthcare support (365) | Farmers and ranchers (021) | Miscellaneous agricultural workers (605) | |

COC, Census Occupation Codes; NAICS, North American Industrial Classification System (The numbers in parentheses signify NAICS 2002 codes or COC 2000 codes).

All other major occupation categories include business and financial operations (050–095); computer and mathematical (100–124); architecture and engineering (130–156); life, physical, and social services (160–196); community and social services (200–206); legal (210–215); arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media (260–296); food preparation and serving related (400–416); personal care and service (430–465); sales and related (470–496); farming, forestry, and fishing (600–613); installation, repair, and maintenance (700–762); military, rank not specified (983).

All other major industry categories include agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (11); mining (21); utilities (22); wholesale trade (42); information (51); finance and insurance (52); real estate and rental and leasing (53); professional, scientific, and technical services (54); management of companies and enterprises (55); arts, entertainment, and recreation (71).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, Zahran HS, King ME, Johnson CA, Liu X. Vital Health Stat. USA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. National Surveillance of Asthma: United States, 2001–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhodes L, Moorman JE, Redd SC. Sex differences in asthma prevalence and other disease characteristics in eight states. J Asthma. 2005;42:777–782. doi: 10.1080/02770900500308387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCallister JW, Mastronarde JG. Sex differences in asthma. J Asthma. 2008;45:853–861. doi: 10.1080/02770900802444187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jajosky RA, Harrison R, Reinisch F, Flattery J, Chan J, Tumpowsky C, Davis L, et al. Surveillance of work-related asthma in selected U.S. states using surveillance guidelines for state health departments – California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey, 1993–1995. MMWR. 1999;48:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toren K, Blanc PD. Asthma caused by occupational exposures is common – a systematic analysis of estimates of the population-attributable fraction. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henneberger PK, Redlich CA, Callahan DB, Harber P, Lemiere C, Martin J, Tarlo SM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society Statement: work-exacerbated asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:368–378. doi: 10.1164/rccm.812011ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reijula K, Haahtela T, Klaukka T, Rantanen J. Incidence of occupational asthma and persistent asthma in young adults has increased in Finland. Chest. 1996;110:50–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kogevinas M, Antó JM, Sunyer J, Tobias A, Kromhout H, Burney P. A population-based study on occupational asthma in Europe and other industrialized countries. Lancet. 1999;353:1750–1754. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz I, Moshe S, Sosna J, Baum GL, Fink G, Shemer J. The occurrence, recrudescence, and worsening of asthma in a population of young adults. Chest. 1999;116:614–618. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karjalainen A, Kurppa K, Martikainen R, Klaukka T, Karjalainen J. Work is related to a substantial portion of adult-onset asthma incidence in the Finnish population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:565–568. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2012146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toren K, Balder B, Brisman J, Lindholm N, Lowhagen O, Palmqvist M, Tunsater A. The risk of asthma in relation to occupational exposures: a case control study from a Swedish city. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:496–501. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13349699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forastiere F, Balmes J, Scarinci M, Tager IB. Occupation, asthma, and chronic respiratory symptoms in a community sample of older women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1864–1870. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9712081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toren K, Ekerljung L, Kim J-L, Hillstrom J, Wennergren G, Ronmark E, Lötvall J, et al. Adult-onset asthma in west Sweden – incidence, sex differences and impact of occupational exposures. Respir Med. 2011;105:1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maestrelli P, Schlunssen V, Mason P, Sigsgaard T. Contribution of host factors and workplace exposure to the outcome of occupational asthma. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:88–96. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00004811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karjalainen A, Kurppa K, Martikainen R, Karjalainen J, Klaukka T. Exploration of asthma risk by occupation – extended analysis of an incidence study of the Finnish population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28:49–57. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarlo SM, Malo JL. An official ATS proceedings: asthma in the workplace: the third jack pepys workshop on asthma in the workplace: answered and unanswered questions. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:339–349. doi: 10.1513/pats.200810-119ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howse D, Gautrin D, Neis B, Cartier A, Horth-Susin L, Jong M, Swanson MC. Gender and snow crab occupational asthma in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Environ Res. 2006;101:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McHugh MK, Symanski E, Pompeii LA, Delclos GL. Prevalence of asthma by industry and occupation in the U.S. working population. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:463–475. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumas O, Donnay C, Heederik DJ, Hery M, Choudat D, Kauffmann F, LeMoual N. Occupational exposure to cleaning products and asthma in hospital workers. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:883–889. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dosman JA, Chenard L, Rennie DC, Senthilselvan A. Reciprocal association between atopy and respiratory symptoms in fully employed female, but not male, workers in swine operations. J Agromedicine. 2009;14:270–276. doi: 10.1080/10599240902772738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics. Exposure Code Lookup. [last accessed 15 May 2013];2012 http://www.aoecdata.org/ExpCodeLookup.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson NJ, Reeb-Whitaker CK, Bonauto DK, Rauser E. Work-related asthma in Washington state. J Asthma. 2011;48:773–782. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.604881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher AM, London MA, Gelberg KH, Grey AJ. Characteristics of patients with work-related asthma seen in the New York State Occupational Health Clinics. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000245920.87676.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System WEAT: Web Enabled Analysis Tool. [last accessed 9 December 2013]; http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/s_broker/weatsql.exe/weat/index.hsql.

- 25.Flattery J, Davis L, Rosenman KD, Harrison R, Lyon Callo S, Filios M. The proportion of self-reported asthma associated with work in three States: California, Massachusetts, and Michigan, 2001. J Asthma. 2006;43:213–218. doi: 10.1080/02770900600566967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knoeller GE, Mazurek JM, Moorman JE. Work-related asthma among adults with current asthma: Evidence from the Asthma Callback Survey, 33 states and District of Columbia, 2006–2007. Pub Health Rep. 2011;126:603–611. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melgert BN, Ray A, Hylkema MN, Timens W, Postma DS. Are there reasons why adults asthma is more common in females? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schatz M, Camargo CA. The relationship of sex to asthma prevalence, health care utilization, and medications in a large managed care organization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:553–558. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Haselkorn T, Chipps BE, Miller DP, Wenzel SE. Gender differences in IgE-mediated allergic asthma in the epidemiology and natural history of asthma: outcomes and treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Asthma. 2006;43:179–184. doi: 10.1080/02770900600566405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCallister JW, Holbrook JT, Wei CY, Parsons JP, Benninger CG, Dixon AE, Gerald LB, et al. Sex differences in asthma symptom profiles and control in the American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. Respir Med. 2013;107:1491–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodge R, Cline MG, Burrows B. Comparisons of asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis diagnoses in a general population sample. Am Rev Respir Disease. 1986;133:981–986. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camp PG, Dimich-Ward H, Kennedy SM. Women and occupational lung disease: sex differences and gender influences on research and disease outcomes. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messing K, Doniol-Shaw G, Haentjens C. Sugar and spice and everything nice: health effects of the sexual division of labor among train cleaners. Int J Health Serv. 1993;23:133–146. doi: 10.2190/AAAF-4XWM-XULT-WCTE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Occupational Safety and Health Standards: Personal Protective Equipment: 1910.134 Respiratory Protection. [last accessed 7 February 2013]; https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=standards&p_id=12716.

- 35.DeMarco R, Locatelli F, Sunyer J, Burney P. Differences in incidence of reported asthma related to age in men and women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:68–74. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9907008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Stefano F, Siriruttanapruk S, McCoach J, Di Gioacchino M, Burge P. Occupational asthma in a highly industrialized region of UK: report from a local surveillance scheme. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;36:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald JC, Keynes HL, Meredith SK. Reported incidence of occupational asthma in the United Kingdom, 1989–97. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:823–829. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.12.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provencher S, Labreche FP, De Guire L. Physician based surveillance system for occupational respiratory diseases: the experience of PROPULSE, Quebec, Canada. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:272–276. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.4.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ameille J, Pauli G, Calastreng-Crinquand A, Vervloet D, Iwatsubo Y, Popin E, Bayeux-Dunglas MC, et al. Reported incidence of occupational asthma in France, 1996–99: the ONAP programme. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:136–141. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemiere C, Boulet LP, Chaboillez S, Forget A, Chiry S, Villeneuve H, Prince P, et al. Work-exacerbated asthma and occupational asthma: do they really differ? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henneberger PK, Derk SJ, Sama SR, Boylstein RJ, Hoffman CD, Preusse PA, Rosiello RA, et al. The frequency of workplace exacerbation among health maintenance organisation members with asthma. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:551–557. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.024786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Report 1040. Washington, DC: BLS Reports; 2013. Feb, Women in the labor force: a databook. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimich-Ward H, Beking K, DyBuncio A, Chan-Yeung M, Du W, Karlen B, Camp PG, et al. Occupational exposure influences on gender differences in respiratory health. Lung. 2012;190:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenman KD, Reilly MJ, Schill DP, Valiante D, Flattery J, Harrison R, Reinisch F, et al. Cleaning products and work-related asthma. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:556–563. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000058347.05741.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]