Abstract

The sickle hemoglobin (HbS) point mutation has independently undergone evolutionary selection at least five times in the world because of its overwhelming malarial protective effects in the heterozygous state. In 1949, homozygous Hb S or sickle cell disease (SCD) became the first inherited condition identified at the molecular level; however, since then, both SCD and heterozygous Hb S, sickle cell trait (SCT), have endured a long and complicated history. Hasty adoption of early mass screening programs for SCD, recent implementation of targeted screening mandates for SCT in athletics, and concerns about stigmatization have evoked considerable controversy regarding research and policy decisions for SCT. Although SCT is a largely protective condition in the context of malaria, clinical sequelae, such as exercise-related injury, renal complications, and venous thromboembolism can occur in affected carriers. The historical background of SCD and SCT has provided lessons about how research should be conducted in the modern era to minimize stigmatization, optimize study conclusions, and inform genetic counseling and policy decisions for SCT.

Historical perspective

Discovery and the heterozygote advantage

Sickle cell disease (SCD) holds the distinction of being the first inherited disease identified at the molecular level. In a landmark 1949 Science publication, Linus Pauling and colleagues outlined a series of elegant experiments that confirmed an intrinsic dissimilarity in the hemoglobin from patients with sickle cell anemia based on electrophoretic mobility patterns, a distinction that had long been hypothesized—based on the known changes in erythrocyte shape that occurred preferentially in deoxygenated venous, rather than oxygenated arterial, beds—but had been notoriously difficult to prove.1 This discovery led to the designation of sickle cell anemia as a “molecular disease”, a term coined by Pauling to describe the phenomenon of a clinical disease caused by a single dysfunctional protein.2 The molecular underpinnings of SCD fascinated scientists of the time, as it had been noted that the heterozygote state, sickle cell trait (SCT), appeared to persist in some populations at a perplexingly high rate given the degree of early mortality of homozygosity (SCD). Prevalences as high as 20%–40% had been described in certain African tribes, Mediterranean populations, and Indian aboriginal groups, and the overlap of the SCT allele frequency patterns and malarial endemicity soon led A.C. Allison to the theory that sickle hemoglobin (HbS) must confer a selective advantage of malarial resistance in the carrier state.3 This hypothesis had been similarly applied by J.B.S. Haldane to explain the persistence of another hemoglobinopathy, β-thalassemia trait, around the same time.4

Since the 1940s and 1950s, considerable research, including epidemiologic studies, experimental protocols, and mathematical models, has been conducted to substantiate the malaria theory of SCT. A recent systematic review using 44 high quality observational studies found a consistently strong protective advantage of SCT on meta-analysis for severe P. falciparum malaria [odds ratio (OR) 0.09; confidence interval (CI) 0.06–0.12)], cerebral malaria (OR 0.07; CI 0.04–0.14), and uncomplicated malaria (OR 0.30; CI 0.20–0.45).5 Rates of asymptomatic P. falciparum parasitemia, however, did not appear to differ between SCT carriers and non-carriers,5 suggesting that sickle hemoglobin does not protect against infection itself, but rather to progression to clinical malaria and its associated childhood mortality. Although the precise mechanism by which SCT confers malarial resistance is unknown, mechanistic models do conform to this epidemiologic observation; experimental studies suggest that SCT’s main protective effects involve enhanced immunity, increased clearance of infected erythrocytes, and reduced parasite growth rather than decreased infectivity.5

Early research efforts

Early research attempts to characterize other potential long-term clinical effects of SCT were greatly limited by nonstandardization of diagnostic approaches for SCT. Although solubility testing and electrophoretic techniques for identifying sickle hemoglobin were first described in 1949,1,6 misclassification of individuals with SCT and SCD occurred routinely due to use of differing diagnostic protocols, incomplete proficiency of laboratory techniques, and unreliability of testing.7 This resulted in a confusing series of early case reports in which SCD-like complications were ascribed to individuals with SCT, including multi-organ failure, cerebral infarct, and acute chest syndrome.8 However, despite intermittent conjecture in the medical literature about the potential complications of SCT at the time, it took until the 1970s for systematic research into the laboratory screening techniques and clinical sequelae of sickling disorders to be prioritized.

Screening initiatives

National screening efforts

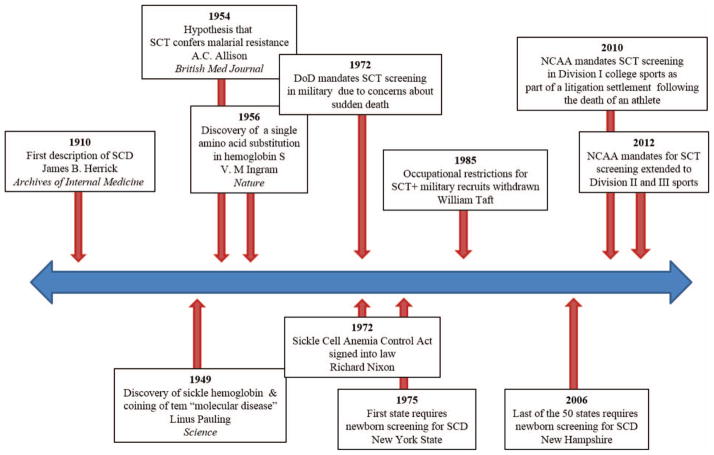

Throughout history, more widespread research efforts into SCT and SCD have been fueled by political agenda, theoretical concerns about safety of affected individuals, and litigation. A timeline of major sickle hemoglobin discoveries and SCT screening mandates is shown in Figure 1. In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed into law the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act, putting forth provisions for SCD which included screening and counseling programs for SCD and SCT, information and educational activities, and research.9 As a result of this legislation, SCD became the first genetic disorder to receive targeted federal recognition and funding.10 Initiatives, such as the launch of a multicenter longitudinal SCD cohort, the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease (CSSCD),11 to study the natural history of SCD and the development of national screening programs for SCD, were a direct consequence of these federal efforts.10 However, initial implementation of screening programs was hasty and flawed, and required major overhaul before the newborn screening program (NBS) was ultimately adopted by all 50 states, spanning from 1975 to 2006. A federal consensus recommendation for universal newborn screening for SCD was not established until 1987, in large part because of a lack of data about the benefits of early detection.10,12 It was not until the landmark Prophylactic Penicillin Study (PROPS)—designed based on epidemiologic observations from the CSSCD of high pneumococcal mortality rates in children—was terminated early after demonstrating the overwhelming efficacy of penicillin prophylaxis, that the NBS gained widespread acceptance.13

Figure 1. Timeline of major discoveries in sickle hemoglobin and sickle cell trait screening mandates.

DoD indicates Department of Defense; and NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Screening in the military

As interest in screening, education, and research in sickling disorders peaked, so did concerns about potential complications of SCT. In 1972, the Department of Defense was enlisted to develop guidelines for SCT testing among its recruits based on published case reports of sudden death and exertional rhabdomyolysis occurring at high altitude among military personnel with SCT.14,15 Initial policies were aimed at universal SCT screening for all Army, Air Force, and Navy recruits with mandatory restrictions for SCT carriers for extreme-altitude activities, such as flight and diving duties.15 By 1985, however, occupational restrictions for SCT carriers were withdrawn because of a lack of evidence for adverse events. Although a subsequent 1987 New England Journal of Medicine article suggested an increased unadjusted risk of sudden death among military recruits with SCT during basic training,16 mandatory duty restriction protocols have not been reinstituted. This continued policy is based, in part, on unpublished data that the adoption of universal preventative measures, such as heat acclimation, hydration, and early detection of exertional injury successfully reduces risk of military occupational death independent of SCT status.17 Currently, SCT screening in the United States Armed Forces is variably performed based on branch-specific requirements. Although the Army ceased universal SCT screening in 1996, the Navy, Air Force, and Marines do still use standard screening protocols for SCT at enrollment. In addition, counseling and notification procedures for positive SCT findings differ widely between branches, with some requiring that individuals with SCT wear identifying tags during training.18

Screening in athletics

More recently, after a nearly 30 year hiatus, SCT testing has again garnered national attention, this time in the context of screening for college athletics. In 2010, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) approved mandatory opt-out SCT testing for its Division I athletes. The policy was adopted as part of a litigation settlement following the death of a 19-year-old freshman during intense football training caused by exertional rhabdomyolysis in the setting of an unknown diagnosis of SCT.19 In 2012, the NCAA later extended its SCT screening mandate to Division II and III athletes in direct response to lawsuits regarding continued SCT-associated deaths.20 Despite requiring SCT screening, the NCAA has not adopted a uniform policy regarding genetic counseling and utilization of positive test results.17,19,20

Screening techniques

By the early 1970s, several screening techniques for SCT had been developed; however, misinterpretation of SCT screening results was common given lack of standardization, inadequate training, and underuse of confirmatory testing. In 1972, as a direct result of the institution of the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act, a Hemoglobinopathy Reference Laboratory was created at the Centers of Disease Control (CDC) to standardize laboratory techniques and interpretation for SCT screening among the newborn screening programs.10 Although the last edition of the reference manual was published in 1984, the Reference Laboratory provided a framework for evaluating test proficiency and for ensuring accuracy of SCT screening results and interpretation.10

Currently, the most common screening techniques include sickle solubility testing, hemoglobin electrophoresis, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and isoelectric focusing (IEF), each with their own advantages and limitations. The sickle solubility test is a low-cost assay that relies on the relative insolubility of HbS in the presence of a reducing agent, such as sodium dithionite, by detecting turbidity or crystal formation from lysis of HbS-containing erythrocytes. Because it only detects the presence or absence of sickle hemoglobin, the solubility test cannot differentiate individuals with SCD and SCT and can be falsely negative in infants with high hemoglobin F or in individuals with very low percentage HbS (<10%), making confirmatory testing essential. Solubility testing is currently used as the first-line technique for SCT screening in the NCAA.19

Hemoglobin electrophoresis, HPLC, and IEF are methods used either for primary identification of SCT or as confirmatory tests. These techniques can provide discrimination and relative quantification of hemoglobins, allowing for differentiation of SCT from SCD syndromes. Hemoglobin electrophoresis, an inexpensive and frequently used technique, uses the principles of gel electrophoresis to separate hemoglobin molecules by size and charge. Comigration of certain rare hemoglobin variants with HbS may obscure the diagnosis with standard electrophoresis; therefore, the use of different gels such as citrate agar or cellulose acetate or IEF methods are often required for further hemoglobin discrimination. IEF is a highly sensitive, discriminatory pH-based electrophoresis technique that identifies hemoglobins by their isoelectric point. Because of its high-throughput capabilities and low-cost, IEF is the primary method used in most newborn screening programs.10 HPLC and capillary electrophoresis have also been adopted for hemoglobinopathy screening by many reference laboratories, owing to their ability to more precisely quantify hemoglobin components.

Molecular protocols for hemoglobinopathies are often used in the research setting to identify SCT carriers using banked DNA samples, especially in studies where hemoglobin electrophoresis samples have not been collected. These methods are also used by a limited number of laboratories to clarify SCT screening results in rare cases.10 Recent rapid advances in technology have allowed for detection of SCT from DNA through exome sequencing, direct genotyping for the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that encodes the sickle mutation (rs334), and even genetic imputation using data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS).21,22

Stigmatization of the heterozygote

The β-globin gene point mutation resulting in sickle hemoglobin has independently undergone evolutionary selection at least 5 times in the world because of its overwhelming malarial protective effects.23 High prevalence areas include Africa, the Middle East, and Indian subcontinent, with SCT affecting up to 300 million individuals worldwide. In the United States, recent statistics demonstrate that incidence of SCT among screened newborns is 73.1 cases per 1000 in African Americans, 6.9 cases per 1000 in Hispanics, and 3.0 per 1000 in whites.24 However, despite the diversity of populations affected, SCD has been historically labeled a “black” disease, a designation that has simultaneously propagated racial stigmatization and a desire to help an underserved community. Nixon’s language within National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act highlighted this tension: “This disease is especially pernicious because it strikes only blacks and no one else… these actions make it clear, I believe, the urgency with which this country is working to alleviate and arrest the suffering from this disease.”9

Stigmatization of mass screening

Stigmatization of genetic diseases can occur as a result of racial discrimination, community fear or mistrust, incomplete knowledge, or concern for the social implications of having a disease (Table 1).25 Stigmatization of SCT carrier status first occurred at a national level in the early 1970s as a result of federally-initiated mass SCT screening efforts. Despite the initial intention to ensure comprehensive genetic and pregnancy counseling, individuals were often not informed or were incompletely educated about their SCT carrier status, resulting in confusion about health risks and mistrust of the underlying intentions for screening. Many blacks felt forced to undergo testing and experienced employment, health insurance, and marriage discrimination.26 SCT screening at the time was compared by some to the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.20 Today, despite the more protocolized newborn screening program (NBS) in the United States, genetic counseling and follow-up for individuals who test positive for SCT remains poor secondary to wide variability in state policies regarding notification. Recent studies suggest that only 16% of polled individuals are aware of their own SCT status,27 with only 37% of parents reporting having received direct notification of the SCT status of their children.28 In this context, SCT screening has been labeled a “neglected opportunity” in its failure to deliver early genetic and reproductive counseling, community empowerment, and greater patient involvement in healthcare decisions.29

Table 1.

Reasons for stigmatization and strategies to mitigate stigmatization among sickle cell trait (SCT) carriers

| Reasons for stigmatization | Strategies to mitigate stigmatization |

|---|---|

| Racial discrimination | Education regarding population prevalence of SCT and its evolutionary advantage Public education about SCT and SCD Avoidance of racially-targeted screening programs Avoidance of labeling terms such as “SCT carrier”, “sickle disease” or “sickler”, instead focusing on education about SCT itself |

| Community fear/mistrust | Assurance of privacy/confidentiality Transparency of screening protocols Accurate SCT testing and confirmatory techniques Community/patient empowerment |

| Incomplete knowledge | Provider education about SCT and differences from SCD Genetic and reproductive counseling for SCT carriers High-quality research initiatives |

| Concern for social or occupational implications | Identification of a clear goal for SCT testing Prescreening counseling Assurance of privacy/confidentiality |

Stigmatization in athletics

The recent NCAA screening mandate has again sparked controversy regarding stigmatization of SCT carriers. The policy has evoked criticism because of its reactionary implementation in response to litigation, use of solubility rather than electrophoresis testing, and concerns that SCT-positive athlete will be denied participation in high-exertion activities, similar to the restrictions initially imposed in the military.17,19 Several organizations, such as the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA), oppose mandatory testing of athletes, citing that universal precautions to prevent exercise-related injury should be adopted instead.17 Despite concerns that athletes who test positive for SCT would perceive discrimination, a recent study of 249 NCAA athletes found that most either disagreed (38.4%) or were unsure (50.8%) whether SCT would result in loss of playing time, suggesting that most participants did not perceive a risk of activity restriction.20 However, a high level of personal health concern about having SCT was endorsed by majority (81.7%), with the highest concern existing among black athletes.20 In contrast, a 2011 study of 370 sports medicine physicians revealed that many recommend exercise modifications for athletes who test positive for SCT, particularly for high-risk environmental conditions, such as altitude or intense training. Furthermore, 63% of providers expressed concern about possible discrimination in sports participation based on SCT status.30 Importantly, coach attitudes have not yet been assessed, therefore true practice patterns remain unknown.

Modern revival of research

The historical context of SCT has provided the medical community with much guidance on the method by which research can, and should, be conducted in the modern era to optimize study design, minimize stigmatization, and inform genetic counseling and follow-up recommendations (Table 2). Both the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and CDC have identified SCT as a research priority, calling for more goal-directed, rigorous approaches to SCT research.31,32 To date, research efforts in SCT have been marred by poor design, small sample size, lack of adjustment for confounders, and the use of low-sensitivity or low-specificity SCT diagnostic procedures. Large-scale, epidemiologic approaches, including well-designed case-control or longitudinal cohort studies, are considered the cornerstone of research in SCT as they can provide a measure of age of onset, time course, effect size, and disease-modifying factors. Translational studies to elucidate the pathophysiology of complications related to SCT can then be applied based on these epidemiologic observations, and future interventional trials for disease-modifying treatments or interventions can be developed. Need for well-designed research is especially pressing in the context of exercise-related complications given its important clinical, social, and policy impact.31,32

Table 2.

Importance of research and characteristics of high-quality epidemiologic studies in SCT

| Importance of research | Characteristics of high-quality studies |

|---|---|

| Quantify absolute and relative risks of complications | Cross-collaboration between hematologists and specialists/experts in the outcome of interest |

| Inform genetic counseling in context of newborn & athletic screening | Adequately-powered study (sufficient sample size of participants and/or outcome endpoints) |

| Guide policy decisions for SCT | Appropriate assessment of genotype with hemoglobin electrophoresis or DNA analysis |

| Inform follow-up guidelines for SCT carriers | Inclusion of an appropriate control group |

| Contribute to health disparities research | Validated outcome measures |

| Increase research initiatives and advocacy in sickle cell-related disorders | Measures and adjustments for all relevant confounders |

| Identify potential interventions such as early screening, treatments, or universal precautions |

The paradigm of high-quality research guiding policy and recommendations has been demonstrated throughout the history of sickling disorders, as in the previously-described CSSCD and PROPS studies that critically informed newborn screening recommendations, and universal precaution studies that influenced military SCT screening policies.13,17 Although concerns exist that ongoing research will lead SCT to be erroneously defined as a “disease” or intensify underlying stigmatization, these historical examples show that high-quality research has the potential to induce the opposite effect by accurately defining absolute and relative risk of complications and addressing critical questions. As a result, well-designed SCT studies can provide evidence-based knowledge to help identify true complications, dispel rumors about false or speculative associations, and ensure that policy decisions are based on accurate data. For example, in 2008, a study found that 37% of renal transplant centers test for and exclude SCT carriers from live kidney donation based solely on scant evidence that SCT was associated with an increased risk of renal abnormalities, such as isosthenuria and hematuria.,33 although outcomes of SCT recipients and donors have not been formally studied. Furthermore, in the context of newborn screening, national survey data suggests that pediatricians and primary care providers either do not provide or feel ill-equipped to provide genetic counseling for parents whose infants screen positive for SCT because of incomplete knowledge and lack of evidence-based recommendations.34 Because genetic testing for SCT is already being performed in several contexts, targeted research into the complications of SCT would ensure that genotypic data is fully and appropriately used in medical decision-making.

Clinical complications in SCT

Although a systematic review of clinical complications of SCT has yet to be conducted, several comprehensive reviews of SCT have been recently published outlining the scientific evidence of complications.35–37 The purpose of this section is to highlight the important and high policy impact epidemiologic studies in SCT and to identify unanswered questions in need of future research (Table 3).

Table 3.

Important clinical complications of sickle cell trait and areas for future epidemiologic research

| Complication | Unanswered questions in SCT |

|---|---|

| Exercise-related injury | Risk of non-fatal exercise complications, such as exertional rhabdomyolysis Modifying factors for exertion-related sudden death (eg, altitude, climate, intensity of activity) Efficacy of universal precautions in athletics |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | Risk of progression to end-stage renal disease Modifying factors for CKD (eg, age, diabetes, hypertension) Efficacy of treatments, such as ACE-I, on disease progression Renal transplant donor and recipient outcomes |

| Venous thromboembolism (VTE) | Risk of arterial events (eg, myocardial infarction, stroke) Interaction of hormonal contraception/pregnancy on VTE risk Risk of recurrent VTE |

| Pregnancy-related complications | Risk of fetal complications, such as fetal loss, prematurity, and low birth weight Risk of maternal complications, such as VTE, pre-eclampsia, and maternal infection (eg, amniotic infection, pyelonephritis, endometritis) |

Exercise-related injury

Of the potential SCT-related complications, exertional injury has garnered the most attention over the past 5 years in response to the NCAA screening mandates in college athletes. SCT-related exercise injury broadly includes the complications of unexplained sudden death, exertional rhabdomyolysis, and heat-associated collapse.38 Although research in this area has been primarily limited to case reports given the rarity of events, few large-scale epidemiologic studies have been performed. The first notable study, published in the New England Journal Medicine, retrospectively reviewed records of 2.1 million military personnel from 1977–1981 and found that of 28 unexplained sudden deaths, 12 occurred in individuals with SCT, resulting in a relative risk (RR) of death that was 39.8 (CI 17–90) times higher among recruits with SCT compared to those without.16 On subgroup analysis, a similarly increased RR was not found for non-sudden death or sudden death explained by pre-existing conditions such as structural heart disease, epilepsy, intracranial bleeding, asthma, medications, or drug abuse. In the setting of athletics, a more recent retrospective review of 273 deaths in the NCAA from 2004–2008 found that the majority of deaths (72%) occurred among football players, of which 12 were categorized as exertion-related, defined as associated with cardiac disease, heat illness, or SCT. Of these deaths, 5 occurred in athletes with SCT, resulting in an estimated absolute risk of death of 1 in 1486 among football players with SCT and RR of 29 (no CI reported) comparing individuals with and without SCT.39 Both studies noted that the absolute number of SCT deaths was small and that all SCT-related mortality occurred with intensive exercise; in the military context, SCT deaths were found to be due to exertional cardiac arrest, heat stroke, or rhabdomyolysis and in the athletic context, all SCT deaths occurred in Division I football athletes during practice or conditioning.16,39

Although these studies suggest an increased risk of exercise-related death in individuals with SCT, their study designs were limited by lack of adjustment for confounders, such as intensity of exercise and underlying comorbidities, and by their inability to assess for modifying factors for sudden death, such as climate and altitude. Future efforts should be aimed at clarifying the context in which SCT-related deaths occur, defining the epidemiology and genetic predispositions for exertional rhabdomyolysis, and formally investigating the utility of universal precautions in preventing overall and SCT-specific exercise-related injury in athletics.17,31,32,35

Renal disease

Renal abnormalities are among the most common manifestations of SCT. The prevalence of hematuria has been noted to be higher among SCT carriers compared to those with normal hemoglobin,40 and the urinary concentrating ability among individuals with SCT has been demonstrated to be associated, in a dose-dependent manner, with sickle hemoglobin percentage.41 In addition, renal medullary carcinoma, a rare aggressive cancer, appears to occur almost exclusively in patients with SCT based on numerous pathology case series.37 However, research into the long-term functional consequences of SCT on kidney function, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD), has only recently been performed. The largest of these studies, published in 2014 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA),21 evaluated the association of SCT with CKD and albuminuria using a pooled analysis of 15 975 self-identified African Americans, of whom 1248 had SCT, from 5 prospective population-based cohorts, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC), Jackson Heart Study (JHS), Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and Coronary Artery Risk Development In Young Adults (CARDIA).21 Of 2233 individuals in the study with CKD, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 239 were found to be SCT carriers, resulting in pooled adjusted OR of 1.57 (CI 1.34–1.84) for CKD comparing individuals with and without SCT. A similar association was found for albuminuria (OR 1.86; CI 1.49–2.31) and decline in eGFR over time (OR 1.32; CI 1.07–1.61); however, an association of SCT and ESRD could not be verified given lack of power.21 These findings were similar among all 5 studies, despite the inherent differences in demographics of each cohort.

Less robust epidemiologic studies evaluating the association of SCT and ESRD, have yielded conflicting results. Two cross-sectional studies have found the prevalence of SCT to be higher than the expected population prevalence among African Americans on dialysis; the first investigated 188 patients from four dialysis centers, noting a SCT prevalence of 14.9% compared to the local newborn screening prevalence of 7.1% in that region (p < 0.001),42 and the second, using an African American hemodialysis cohort of 5319 individuals, found a prevalence of SCT of 10.2%, which was higher than general newborn screening estimates.43 Using a case-control design of 2081 African Americans with ESRD and 1177 controls without kidney disease, the adjusted odds of SCT were not higher among those with ESRD compared to those without (OR 1.05 [CI 0.79–1.40]).44 These studies have been criticized for their purely descriptive analysis, lack of appropriate or adequately-sized control groups, and inability to account for all applicable confounders.

The association of SCT and CKD is clear, although its age of risk-onset and risk of progression to ESRD has not been established. Furthermore, the modifying effect of SCT on the development of diabetic, hypertensive, and apolipoprotein L1 gene (APOL1) risk variant-associated nephropathy on SCT-related CKD has yet to be evaluated. In addition, studies investigating the effect of treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,45 which have been shown to have benefit in delaying the progression of albuminuria in SCD, are needed. Because SCT screening is already variably being performed in renal transplant donor evaluations,33 future research efforts should also be dedicated to evaluating renal transplant donor and recipient outcomes in SCT.

Venous thromboembolism

An increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in individuals with SCT has long been hypothesized. The first major large-scale effort, a 1979 New England Journal of Medicine Veterans Administration database study of hospitalized African Americans, found that 108 of 4900 (2.2%) patients with SCT were diagnosed with pulmonary embolism (PE) compared to 276 of 18 292 (1.5%) of patients with normal hemoglobin (p < 0.001).40 Of the hospital records obtainable for physician review, the prevalence of coexisting “thrombophlebitis” also appeared to be higher among SCT carriers compared with controls (34% vs 12%; p < 0.001).40 Although suggestive of an association, these analyses were unadjusted and were limited by diagnostic methodologies available at the time.

More recently, 2 studies have more conclusively demonstrated a moderately increased risk of VTE among individuals with SCT compared to controls with hemoglobin AA, with both studies interestingly finding that the high total VTE risk is almost entirely due to an increased risk of PE rather than deep vein thrombosis (DVT).46,47 The first of these studies, a case-control of 515 self-identified hospitalized African Americans with recently diagnosed VTE and 555 outpatient controls, demonstrated that cases with VTE had 1.8-fold (CI 1.1–2.8) increased adjusted odds of having SCT compared with controls. The odds of having SCT among those with PE was much higher (OR 3.9; 2.2–6.9) compared with DVT (OR 1.1; 0.65–1.9).46 A similar association was demonstrated in a recent prospective study of 4028 self-reported African American participants in the ARIC study. After a median follow-up of 22 years, individuals with SCT had an increased adjusted risk of developing a first VTE [hazard ratio (HR) 1.50; CI 0.96–2.36, which was almost completely explained by the risk of PE (HR 2.05; CI 1.12–3.76) compared to DVT (HR 1.15; CI 0.58–2.27) on subgroup analysis.47

Although underlying hypercoagulability with SCT has been hypothesized, thus far epidemiologic evidence has only consistently supported an association of SCT with venous thrombosis rather than arterial events. Future well-designed, large-scale studies are required to clarify the risk of arterial events, if present, in individuals with SCT. In terms of VTE, studies to define the recurrence rate in SCT-related VTE are much needed. Few reports have also suggested that SCT may modify the risk of VTE in the setting of hormonal contraception and pregnancy48,49; however, further research is urgently needed to elucidate this relationship.

Pregnancy-related complications

Several studies have investigated the association of SCT with pregnancy complications; however, thus far, the research in this area has been limited by poor study design or insufficient sample size. A single retrospective analysis of 24 882 pregnant females demonstrated a trend toward an increased unadjusted risk of VTE for SCT carriers during pregnancy (RR 2.7; 0.6–13]), although these results were based on only 2 VTE events.49 The authors of this report note that an adequately-powered study for VTE, which is a rare outcome, would require a sample size of >100 000 pregnancies.

Although several small cohort studies have found an increased unadjusted prevalence of pregnancy complications, such as miscarriage, preeclampsia, prematurity, low birth weight, and maternal infection in SCT,50–53 numerous additional cohort investigations, all with larger sample sizes and adjustment for confounders, have failed to demonstrate an increased risk of poor pregnancy outcomes among SCT carriers.54–56 Of the pregnancy-associated complications, asymptomatic bacteriuria has shown the most consistent associations with SCT in the literature.55,57

The association between SCT and both maternal and fetal pregnancy-related complications remains unclear. Well-designed case-control studies or large-scale, multi-institutional epidemiologic efforts are needed to clarify pregnancy risks in SCT carriers.

Conclusion

Because screening for SCT is currently being performed, and is mandated, in several contexts, high-quality research efforts are needed to inform genetic counseling and policy decisions. The historical context of SCD and SCT can provide guidance on how research can best be performed to minimize stigmatization. Well-designed large-scale epidemiologic studies should be pursued to answer critical questions in SCT.

Learning Objectives.

To summarize the historical context of research and screening initiatives in sickle cell trait (SCT)

To review common screening techniques for SCT in practice and research settings

To outline the importance and characteristics of high-quality epidemiologic research in SCT

To describe the major clinical complications of SCT and highlight areas for future research

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants K08HL125100 (R.P.N.) and K01HL108832 (C.H.).

Footnotes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors have received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

- 1.Pauling L, Itano HA. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science. 1949;109(2835):443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gormley M. The first “molecular disease”: a story of Linus Pauling, the intellectual patron. Endeavour. 2007;31(2):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.endeavour.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison AC. The distribution of the sickle-cell trait in East Africa and elsewhere, and its apparent relationship to the incidence of subtertian malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1954;48(4):312–318. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(54)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lederberg J. JBS Haldane (1949) on infectious disease and evolution. Genetics. 1999;153(1):1–3. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor SM, Parobek CM, Fairhurst RM. Haemoglobinopathies and the clinical epidemiology of malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(6):457–468. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itano HA, Pauling L. A rapid diagnostic test for sickle cell anemia. Blood. 1949;4(1):66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt RM, Brosious EM. Evaluation of proficiency in the performance of tests for abnormal hemoglobins. Am J Clin Pathol. 1974;62(5):664–669. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/62.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenk EA. Sickle Cell trait and superior longitudinal sinus thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1964;60:465–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-60-3-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The American Presidency Project. [Accessed April 29, 2015];Richard Nixon, Statement on Signing the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act. 1972 May 16; ( http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=3413)

- 10.Benson JM, Therrell BL., Jr History and current status of newborn screening for hemoglobinopathies. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34(2):134–144. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaston M, Rosse WF. The cooperative study of sickle cell disease: review of study design and objectives. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1982;4(2):197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Consensus conference. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies. 1987;258(9):1205–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaston MH, Verter JI, Woods G, et al. Prophylaxis with oral penicillin in children with sickle cell anemia: a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(25):1593–1599. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606193142501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones SR, Binder RA, Donowho EM., Jr Sudden death in sickle-cell trait. N Engl J Med. 1970;282(6):323–325. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197002052820607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodine CE, Uddin DE. Medical aspects of sickle hemoglobin in military personnel. J Natl Med Assoc. 1977;69(1):29–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kark JA, Posey DM, Schumacher HR, Ruehle CJ. Sickle-cell trait as a risk factor for sudden death in physical training. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(13):781–787. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709243171301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson AA. Sickle cell trait testing and athletic participation: a solution in search of a problem? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:632–637. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell BL. Sickle cell trait and sudden death: bringing it home. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(3):300–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonham VL, Dover GJ, Brody LC. Screening student athletes for sickle cell trait: a social and clinical experiment. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(11):997–999. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1007639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence RH, Shah GH. Athletes’ perceptions of National Collegiate Athletic Association-mandated sickle cell trait screening: insight for academic institutions and college health professionals. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(5):343–350. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.902840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naik RP, Derebail VK, Grams ME, et al. Association of sickle cell trait with chronic kidney disease and albuminuria in African Americans. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2115–2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auer PL, Johnsen JM, Johnson AD, et al. Imputation of exome sequence variants into population- based samples and blood-cell-trait-associated loci in African Americans: NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(5):794–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elion J, Berg PE, Lapoumeroulie C, et al. DNA sequence variation in a negative control region 5′ to the beta-globin gene correlates with the phenotypic expression of the beta s mutation. Blood. 1992;79(3):787–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ojodu J, Hulihan MM, Pope SN, Grant AM Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Incidence of sickle cell trait: United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(49):1155–1158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markel H. The stigma of disease: implications of genetic screening. Am J Med. 1992;93(2):209–215. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90052-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culliton BJ. Sickle cell anemia: national program raises problems as well as hopes. Science. 1972;178(4058):283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4058.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treadwell MJ, McClough L, Vichinsky E. Using qualitative and quantitative strategies to evaluate knowledge and perceptions about sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(5):704–710. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavanagh PL, Wang CJ, Therrell BL, Sprinz PG, Bauchner H. Communication of positive newborn screening results for sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait: variation across states. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148C(1):15–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor C, Kavanagh P, Zuckerman B. Sickle cell trait: neglected opportunities in the era of genomic medicine. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1495–1496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acharya K, Benjamin HJ, Clayton EW, Ross LF. Attitudes and beliefs of sports medicine providers to sickle cell trait screening of student athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(6):480–485. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31822e8634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant AM, Parker CS, Jordan LB, et al. Public health implications of sickle cell trait: a report of the CDC meeting. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(6 Suppl 4):S435–S439. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldsmith JC, Bonham VL, Joiner CH, Kato GJ, Noonan AS, Steinberg MH. Framing the research agenda for sickle cell trait: building on the current understanding of clinical events and their potential implications. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(3):340–346. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reese PP, Hoo AC, Magee CC. Screening for sickle trait among potential live kidney donors: policies and practices in US transplant centers. Transpl Int. 2008;21(4):328–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kemper AR, Uren RL, Moseley KL, Clark SJ. Primary care physicians’ attitudes regarding follow-up care for children with positive newborn screening results. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1836–1841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Key NS, Connes P, Derebail VK. Negative health implications of sickle cell trait in high income countries: from the football field to the laboratory. Br J Haematol. 2015;170(1):5–14. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Key NS, Derebail VK. Sickle-cell trait: novel clinical significance. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:418–422. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsaras G, Owusu-Ansah A, Boateng FO, Amoateng-Adjepong Y. Complications associated with sickle cell trait: a brief narrative review. Am J Med. 2009;122(6):507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connor FG, Bergeron MF, Cantrell J, et al. ACSM and CHAMP summit on sickle cell trait: mitigating risks for warfighters and athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(11):2045–2056. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31826851c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Klossner D, Asif IM. Sickle cell trait associated with a RR of death of 37 times in National Collegiate Athletic Association football athletes: a database with 2 million athlete-years as the denominator. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):325–330. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heller P, Best WR, Nelson RB, Becktel J. Clinical implications of sickle-cell trait and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in hospitalized black male patients. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(18):1001–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905033001801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta AK, Kirchner KA, Nicholson R, et al. Effects of alpha-thalassemia and sickle polymerization tendency on the urine-concentrating defect of individuals with sickle cell trait. J Clin Invest. 1991;88(6):1963–1968. doi: 10.1172/JCI115521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Derebail VK, Nachman PH, Key NS, Ansede H, Falk RJ, Kshirsagar AV. High prevalence of sickle cell trait in African Americans with ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):413–417. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derebail VK, Lacson EK, Jr, Kshirsagar AV, et al. Sickle Trait in African-American Hemodialysis Patients and Higher Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Dose. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(4):819–826. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013060575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hicks PJ, Langefeld CD, Lu L, et al. Sickle cell trait is not independently associated with susceptibility to end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2011;80(12):1339–1343. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Falk RJ, Scheinman J, Phillips G, Orringer E, Johnson A, Jennette JC. Prevalence and pathologic features of sickle cell nephropathy and response to inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(14):910–915. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204023261402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Austin H, Key NS, Benson JM, et al. Sickle cell trait and the risk of venous thromboembolism among blacks. Blood. 2007;110(3):908–912. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Folsom AR, Tang W, Roetker NS, et al. Prospective study of sickle cell trait and venous thromboembolism incidence. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(1):2–9. doi: 10.1111/jth.12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Austin H, Lally C, Benson JM, Whitsett C, Hooper WC, Key NS. Hormonal contraception, sickle cell trait, and risk for venous thromboembolism among African American women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):620, e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Porter B, Key NS, Jauk VC, Adam S, Biggio J, Tita A. Impact of sickle hemoglobinopathies on pregnancy-related venous thromboembolism. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(9):805–809. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor MY, Wyatt-Ashmead J, Gray J, Bofill JA, Martin R, Morrison JC. Pregnancy loss after first-trimester viability in women with sickle cell trait: time for a reappraisal? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(6):1604–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rimer BA. Sickle-cell trait and pregnancy: a review of a community hospital experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;123(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larrabee KD, Monga M. Women with sickle cell trait are at increased risk for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(2):425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown S, Merkow A, Wiener M, Khajezadeh J. Low birth weight in babies born to mothers with sickle cell trait. JAMA. 1972;221(12):1404–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan TL, Seed P, Oteng-Ntim E. Birthweights in sickle cell trait pregnancies. BJOG. 2008;115(9):1116–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tita AT, Biggio JR. Fetal loss and sickle cell trait: a valid association? [corrected] Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.11.010. author reply e18–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stamilio DM, Sehdev HM, Macones GA. Pregnant women with the sickle cell trait are not at increased risk for developing preeclampsia. Am J Perinatol. 2003;20(1):41–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baill IC, Witter FR. Sickle trait and its association with birthweight and urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1990;33(1):19–21. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(90)90649-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]