Abstract

Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) are promising therapeutic agents for treating traumatic brain injury (TBI). Using computational and medicinal methods, the structure-activity relationship of a class of acyl-2-aminobenzimidazoles (1-26) is reported. The new compounds are designed based on the chemical structure of 3,3’-difluorobenzaldazine (DFB), a known mGluR5 PAM. Ligand design and prediction of binding affinities of the new compounds have been performed using the site identification by ligand competitive saturation (SILCS) method. Binding affinities of the compounds to the transmembrane domain of mGluR5 have been evaluated using nitric oxide (NO) production assay, while the safety of the compounds is tested. One new compound found in this study, compound 22, showed promising activity with an IC50 value of 6.4 μM, which is ~20 fold more potent than that of DFB. Compound 22 represents a new lead for possible development as a treatment for TBI and related neurodegenerative conditions.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Metabotropic glutamate receptor, Neuroprotection, Computer-aided drug design, Positive allosteric modulator

Graphic Abstract

1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) represents a serious public health problem, with >1.7 million new cases and >50,000 deaths annually in the United States.1 TBI induces biochemical and cellular changes that contribute to delayed tissue damage.2-5 Such secondary injury begins within seconds to minutes after trauma and may continue for months to years;6,7 it involves a complex cascade of biochemical and metabolic changes that contribute to chronic functional deficits.8

As key mediators of CNS inflammation, microglia play a complex role in the brain response to injury.9 After TBI, microglia become activated undergoing morphological changes,10 followed by proliferation and migration toward the site of injury.11 Activated microglia can result in increased phagocytosis, up-regulation of antigen-presenting capabilities, and secretion of pro-inflammatory molecules (e.g., TNFα and IL1β1), reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS).12 After TBI, numerous studies have shown that activation of microglia can contribute to neuronal cell death.13 Numerous microglial-related genes are activated rapidly after TBI,14-16 and some show persistent elevated expression for months.15,17 More recently, we have shown persistent microglial activation associated with markers of oxidative stress and progressive neurodegeneration 12 months after TBI in mice.13

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are family III G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are classified into three subgroups (subgroup 1: mGluR1 and -5, subgroup 2: mGluR2 and -3, subgroup 3: mGluR4, -6, -7 and -8) based on pharmacological profiles and signal transduction pathways. Among subgroup 1 receptors, mGluR5 is commonly found in neurons and astrocytes. It has been shown that mGluR5, but not mGluR1, is highly expressed in microglial cells.15 Activation of mGluR5 using single dose treatment of the orthosteric mGluR5 agonist CHPG can markedly inhibit microglial activation, even when administered as late as one month after experimental trauma.13 mGluR5 agonists can also block the neurotoxic effects of activated microglia in vitro and in vivo.13,18,19 In sum, the experimental evidence demonstrated that mGluR5 is a promising neuroprotective drug target for TBI. However, available selective orthosteric mGluR5 agonists show little penetration through the blood brain barrier (BBB). In contract positive allosteric modulators are effective systemically. Recently we have shown that early systemic administration of an mGluR5 PAM can limit both posttraumatic neuroinflammation and related tissue loss and behavioral dysfunction.19

The structure of mGluR5 includes a large (~560 amino acids) N-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) that is linked, through a cysteine rich domain, to a seven-helical transmembrane (TM) domain. Numerous mGluR5 agonists targeting the LBD are known, although none has shown high selectivity, largely due to the high sequence similarity in the LBD of the three sub-families of mGluRs.8 Moreover, the mGluR LBD share sequence similarity with other receptors such as calcium-sensing receptors and the pheromone receptors,9 leucine/isoleucine/valine-binding protein (ILVBP), ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)B receptors.20 As a consequence, the development of potent, selective, and clinically useful agonists of mGluR5 has been challenging.9

To overcome this limitation, an alternative strategy is to synthesize positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of mGluR5 by targeting the seven-helical trans-membrane (TM) region of the receptor. PAMs offer an excellent opportunity to target mGluR5 as they have greater potential for specificity versus the other mGluR proteins and have a higher potential for CNS penetration as compared to LBD binders, which typically require the presence of charged amino and carboxylate groups. To date, various PAMs of mGluR5 have been reported such as DFB,21 CPPHA,22,23 CDPPB,12,13 ADX-47273,24 MPEP-based pyrimidines,25 and nicotinamides.26 While PAMs of mGluR5 have shown promising in vivo efficacy for TBI,19 and have been used clinically in brain disorders such as anxiety and psychotics,27 none has been used for the treatment of TBI.

Recently, we have evaluated a collection of mGluR5 PAMs for their neuroprotective activities.28 Our results indicated that DFB demonstrated the most promising activities, with the potency of 136 μM (IC50 for NO production).28 However, this PAM, along with other tested PAMs, has limitations due to poor solubility, significant neuron toxicity, and modest efficacy. These drawbacks limit their potential clinical applicability for TBI. Here we test the hypothesis that novel neuroprotective agent with improved potency may be developed by mimicking the chemical structure of DFB, using a combination of computer-aided drug design (CADD), synthetic chemistry and biological evaluations.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. CADD

DFB has an azo moiety that is light sensitive, making it a poor candidate for further development into a therapeutic agent. To develop more drug-like compounds we undertook CADD analysis of the PAM binding region of the TM of mGluR5. CADD analysis involved the site identification by ligand competitive saturation (SILCS) approach on a homology model of the TM of mGluR5 derived from the mGluR1 crystal structure (PDB: 4OR2).29 We note that prior to the availability of this crystal structure, the β2-adrenergic receptor (PDB: 3NYA) was used as a template for the homology modeling and our initial SILCS analysis was based on that model. Although the details of the spatial distribution of the SILCS FragMaps and the binding poses of the ligands are different between the homology models of mGluR5 derived from β2-adrenergic and mGluR1, ligand interactions with L743 and W784, identified to be important for activation30 were preserved across both the systems. Presented below is the analysis from SILCS simulations with the mGluR5 model derived from the mGluR1 structure.

SILCS is a method that maps the functional group affinity patterns of a protein.31 The method accounts for both protein flexibility and desolvation contributions by running molecular dynamics (MD) of the protein in an aqueous solution of the small solute molecules representative of different chemical functional groups.32 To sample the partially occluded ligand binding pocket of the mGluR5, we applied an extension of the SILCS method that involves an iterative GCMC/MD methodology.33 From the simulations, discretized probability distributions of the fragment atoms that are normalized by their bulk values are obtained and then converted to free energies based on a Boltzmann distribution, yielding Grid Free Energy (GFE) FragMaps. The maps thus represent the 3D free energy distribution of functional group binding at the LBP and may be used both qualitatively and quantitatively to direct ligand design. In the current work, eight representative solutes with different chemical functionalities: benzene, propane, acetaldehyde, methanol, formamide, imidazole, acetate and methylammonium were chosen to probe the ligand binding pocket of mGluR5. Benzene and propane serve as probes for nonpolar functionalities. Methanol, formamide, imidazole and acetaldehyde are neutral molecules that participate in hydrogen bonding. The positively charged methylammonium and negatively charged acetate molecules serve as probes for charged donor and acceptors, respectively. The voxel occupancies of the eleven atom types were merged in the following manner to create the following five generic FragMap types: (1) generic nonpolar, APOLAR (benzene and propane carbons); (2) generic neutral hydrogen bond donor, HBDON (methanol, formamide and imidazole polar hydrogens); (3) generic neutral hydrogen bond acceptor, HBACC (methanol, formamide, and acetaldehyde oxygen and imidazole unprotonated nitrogen) (4) positive donor, POS (methylammonium polar hydrogens); and (5) negative acceptor, NEG (acetate oxygens).

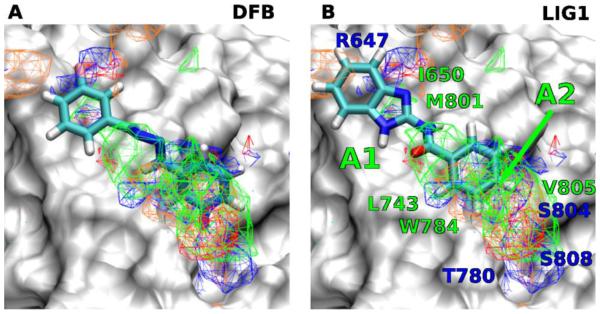

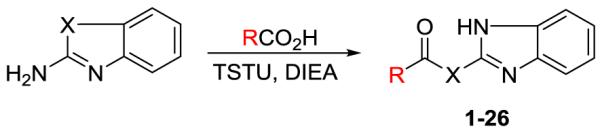

Favorable FragMap affinities were found near residues R647, L743, T780 and W784, previously identified through mutational studies to be important for ligand binding and activity.30 Presented in Figure 1A is DFB docked into the PAM binding site using Autodock-Vina34 directed by the SILCS FragMaps. The phenyl moiety overlaps with the APOLAR FragMaps in the proximity of L743, W784 and V805 (marked A2 in Figure 1B) indicating this region of the model to be important for binding.

Figure 1.

FragMaps overlaid on the PAM binding site of mGluR5 with ligands A) DFB, B) Compound 1. Receptor atoms occluding the view of the binding pocket were removed to facilitate visualization. The color for nonpolar (APOLAR), neutral donor (HBDON), neutral acceptor (HBACC), negative acceptor (NEG) and positive donor (POS) FragMaps are green, blue, red, orange and cyan, respectively. APOLAR, HBACC and HBDON FragMaps are set to a cutoff of −0.5 kcal/mol, while NEG and POS are set to −1.2 kcal/mol. Distinct FragMap affinities that overlap with the functional groups of the ligands are indicated by arrows colored the same as the FragMaps.

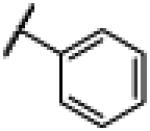

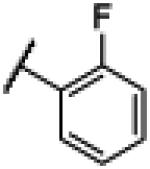

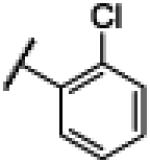

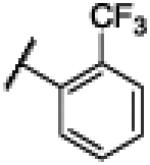

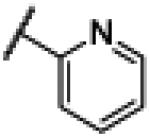

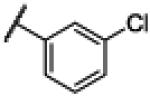

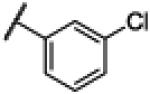

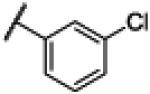

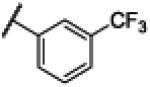

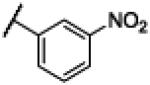

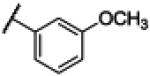

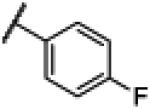

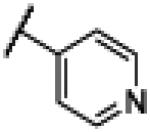

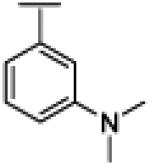

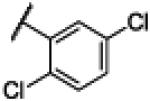

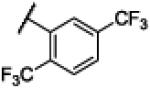

This information motivated the design of a novel benzoyl-2-benzimidazole scaffold (1) to mimic DFB (Scheme 1) and bind in the PAM region of the TM. The azo linker of DFB is of importance in keeping the extended planar configuration of the agonist, however, the azo group is light-sensitive and synthetically problematic. We hypothesize that drug-like, photo-stable compounds can be achieved by substituting the azo linker of DFB with an amide group that are commonly used by natural and synthetic drugs (Scheme 1). The carbonyl group of the amide linker can form an intramolecular H-bonding interaction with the nitrogen atom of the benzimidazole NH, and therefore, keep the overall extended planar configuration of compound 1 similar to that of DFB. In addition, the NH group of the amide linker could also provide hydrogen bond interaction with the backbone of the TM of mGluR5 such as M801, which might further improve the potency of inhibitor. Docking of 1 into the SILCS FragMaps was then performed with the resulting orientation shown in Figure 1B. A collection of 25 derivatives of 1 were then designed and synthesized based on LogP values and overlap with FragMaps in the region of the hydrophobic cavity and the donor and acceptor FragMaps in the proximity of T780, S804 and S808 (Table 1). It is noted that we designed a collection of compounds with a range of logP values with the goal of achieving new compounds with improved aqueous solubility. The TM domain-targeting PAMs commonly have high logP values, which limited the solubility of the resulting PAMs. To address this issue, we synthesized and tested molecules that represent a wide range of logP values. APOLAR FragMaps extended beyond the region of compound 1 occupied by the phenyl ring, suggesting the addition of non-polar functionality to the ring would increase affinity of the ligand to the PAM pocket. In addition, both NEG and HBACC maps are present in that region suggesting the addition of hydrogen bond acceptors to the ring, such as nitro groups or conversion of the phenyl to a pyridine moiety.

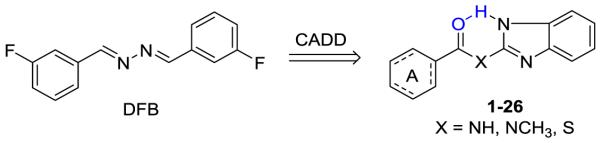

Scheme 1.

Design of compounds 1-26 based on the chemical structure of DFB.

Table 1.

Comparison of structure features, calculated properties, potency and cell viability of compounds 1-26

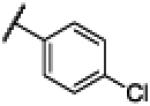

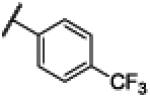

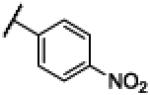

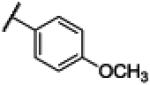

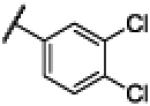

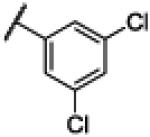

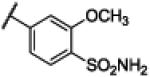

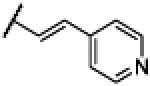

| entry | cmpd | R | X | LogPa | LGFE (kcal/mol) |

IC50c

(μM) |

Viabilityc,d

(μM) |

Selective Index (viability/IC50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DFB | −21.15 | 136 | 500 | 3.68 | |||

| 2 | 1 |

|

NH | 2.76 | −21.57 | 160 | 1000d | 6.17 |

| 3 | 2 |

|

NH | 2.65 | −21.37 | 36 | 1000d | 28.0 |

| 4 | 3 |

|

NH | 3.35 | −20.28 | 110 | 300 | 2.67 |

| 5 | 4 |

|

NH | 3.33 | −19.36 | 88 | 1000d | 11.3 |

| 6 | 5 |

|

NH | 1.44 | −19.04 | N.D.b | N.D.b | N.D.b |

| 7 | 6 |

|

NH | 3.35 | −19.14 | 29 | 1000d | 34.6 |

| 8 | 7 |

|

NCH3 | 3.33 | −24.49 | 210 | 1000d | 4.85 |

| 9 | 8 |

|

S | 3.70 | −21.63 | 160 | 1000d | 6.36 |

| 10 | 9 |

|

NH | 3.33 | −23.9 | 12 | 200 | 17.2 |

| 11 | 10 |

|

NH | 2.63 | −18.22 | 29 | 1000d | 34.6 |

| 12 | 11 |

|

NH | 2.70 | −15.85 | 120 | 1000d | 8.06 |

| 13 | 12 |

|

NH | 2.65 | −19.84 | 15 | 1000d | 67.1 |

| 14 | 13 |

|

NH | 3.35 | −22.38 | 25 | 1000d | 40.4 |

| 15 | 14 |

|

NH | 3.33 | −23.06 | 59 | 1000d | 16.9 |

| 16 | 15 |

|

NH | 2.63 | −19.41 | 33 | 300 | 9.20 |

| 17 | 16 |

|

NH | 2.70 | −17.71 | 100 | 1000d | 10.1 |

| 18 | 17 |

|

NH | 1.44 | −18.26 | 49 | 1000d | 20.2 |

| 19 | 18 |

|

NH | 2.78 | −17.87 | 20 | 300 | 14.7 |

| 20 | 19 |

|

NH | 3.97 | −22.89 | 12 | 100 | 8.33 |

| 21 | 20 |

|

NH | 4.33 | −19.86 | 34 | 60 | 1.74 |

| 22 | 21 |

|

NH | 3.90 | −23.89 | 9.8 | 100 | 10.2 |

| 23 | 22 |

|

NH | 3.97 | −24.23 | 6.4 | 800 | 125 |

| 24 | 23 |

|

NH | 1.05 | −14.74 | 150 | 1000d | 6.59 |

| 25 | 24 |

|

NH | 2.19 | −20.20 | 22 | 1000d | 44.8 |

| 26 | 25 |

|

NH | 3.14 | −23.31 | 42 | 1000d | 24.1 |

| 27 | 26 |

|

NH | 1.89 | −21.52 | 15 | 60 | 3.97 |

It was calculated using ACD/Labs Suite 5.0.

It was not determined due to the poor solubility of the compound.

The listed result was the average of three independent experiments.

The highest concentration of the tested compound at which no obvious cytotoxicity was observed.

Quantitative predictions of the binding of DFB, compound 1, and its derivatives in the pocket were then performed using Ligand Grid Free Energy (LGFE) scoring 32. LGFE is based on the overlap of atoms in the ligand functional moieties with their respective GFE FragMap types and was calculated as a Boltzmann average over 50,000 steps of MC sampling of each of the ligands in the field of FragMaps (Table 1). Two binding orientations were considered: 1) the benzimidazole moiety overlapping with the apolar A1 density (Figure 1B) and 2) with a 180 degree rotation of the ligand leading to benzimidazole overlapping with the A2 density, with individual MC sampling performed starting from each orientation. In addition, individual MC sampling was also performed for the two possible rotamers of the ortho- and meta-substituted compounds. When multiple starting conformations were used, the LGFE scores were based on the Boltzmann weighted average over all MC runs. Presented in Table 1 are the resulting LGFE scores. Notably, a number of the designed compounds were predicted to have improved affinity over 1, while others were predicted to be worse binders, indicating that the design strategy would yield improved analogs. Given the commercial availability of the substituted benzoic acids required for synthesis of 2-26 as well as the need to sample a range of logP values that would also play a role in the biological activity we undertook synthesis of all the compounds in Table 1 and subsequent biological evaluation.

2.2. Chemistry

As shown in Scheme 2, substituted benzoic acid reacted with 2-aminobenzimidazole, N-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-amine, or 1H-benzo[d]imidazole-2-thiol, in the presence of (O-(N-succinimidyl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyl uranium tetrafluoroborate) (TSTU) and diisopropylethyl amine (DIEA) to generate compounds 1-26 in good to excellent yields. The synthesized and purified compounds were the purified and subjected to biological evaluation.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 1-26.

2.3. Inhibition of NO production

The immortalized murine BV2 microglial cell line is a commonly used for mGluR5 PAM screening to investigate microglial mGluR5 receptor activation.18 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated microglial activation was used in present study and the inhibitory potency of compounds 1-26 as PAMs of mGluR5 was evaluated by the nitric oxide (NO) production assay. In addition, cell viability was measured to assess cytotoxicity of these compounds using the CytoTox96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Table 1). N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzamide 1 showed similar inhibitory potency to that of DFB28 in the NO production assay, with improved cell viability (entry 2). No significant improvement was detected for compounds with an ortho-substituent (entries 3-5). The potency of compound 5 was not obtained due to the low solubility of this compound (entry 6). N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-chlorobenzamide 6 showed a 4.7-fold increase in potency compared to DFB, as well as good cell viability (entry 7). Methylation of the amide NH group (entry 8) or substitution of the NH with an S atom (entry 9) of compound 6 let to compounds with significantly decreased potency. Other groups at the meta-position were also visited. The trifluoromethyl analog 9 indicated an 11.7-fold increase in potency compared to DFB; however, this compound was cytotoxic at higher concentrations (entry 10). The potency and cell viability of compound 10 were the same to those of compound 6, while for electro-donating methoxy group-containing compound 11, the potency dropped significantly (entry 12). For para-substituted analogs (entries 13-17), we found that the ones with electro-withdrawing substituents (e.g., F, Cl, NO2 and CF3) indicated good potency and cell viability, while decreased inhibitory activity was observed when methoxy group was employed at the same position. Although N-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)nicotinamide 17 (entry 18) and N-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-(dimethylamino)benzamide 18 (entry 19) showed improved aqueous solubility, no improvement in potency was observed for these compounds. Various di-substituted analogs were also tested (entries 20-24). Compared to DFB, N-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2,5-dichlorobenzamide 19, N-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2,5-di-(trifluoromethyl) benzamide 20 and N-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3,4-dichlorobenzamide 21 (entry 22) indicated 11-fold, 4.0-fold and 14-fold increase in potency, respectively. However, the cell viability of these compounds was lower. The 3,5-dichloro analog, compound 22, indicated the highest potency (IC50 = 6.4 μM) of the class, and low cytotoxic effects (entry 23). N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-methoxy-4-sulfamoylbenzamide 23 showed poor potency (entry 24). (E)-N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamide 24, employing an extended structure, showed good potency and good cell viability (entry 25). Replacement of the aromatic ring with a cyclohexyl group yielded a weaker compound 25 (entry 26). The cyclobutyl analog 26 showed good potency however, it was largely due to the toxicity of the compound to the cells (entry 27).

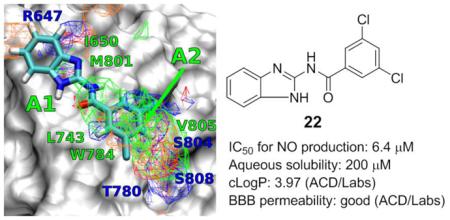

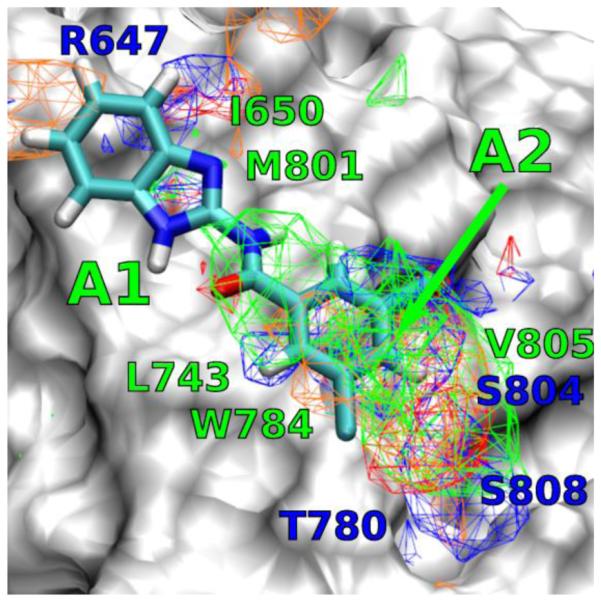

The binding mode of compound 22 has been studied using Autodock-Vina directed by the SILCS FragMaps.34 It is shown in Figure 3 that compound 22 fits snugly into the DFB binding site, and overlaps with the different FragMap. Compound 22 adopts an extended flat configuration through an intramolecular H-bonding between the carbonyl O and the imidazole NH. The benzimidazole moiety of compound 22 occupies the apolar cavity formed between residues L710 of TM4 and V739, V740 and P742 of TM5 (marked A1 in Figure 3). The 3,5-dichlorophenyl moiety occupies the second apolar cavity defined by residues L743 of TM5, W784 of TM6 and V805 of TM7 (marked A2 in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Docking result for the binding mode of compound 22 in the DFB site.

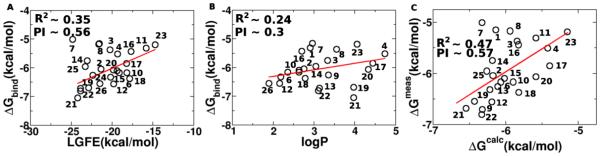

Given the availability of the biological data, further analysis of the utility of the SILCS LGFE data was undertaken. Conversion of the IC50 values to binding free energies (ΔGbind=kBTlog(IC50), kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature) allows for correlation analysis and calculation of the predictive index (PI)35 with respect to the LGFE scores. Based on all compounds in Table 1 this analysis results in PI ~ 0.4 and R2 ~ 0.15. However, of the analogs two, 7 and 8, contain variations of the 5-membered ring structure and are poorly predicted by the LGFE scores; removing them from the correlation analysis yields PI ~ 0.56 and R2 ~ 0.35, with results shown on Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

Correlation plots between A) LGFE, B) logP and ΔGbind calculated from IC50. C) Multiple regression analysis between ΔGbind and both LGFE and logP is used to calculate ΔGcalc. Note, 7 and 8 are not included in the R2 and PI calculations in A) and C).

Potential confounding factors in the experimental data needs to be considered in correlations between ΔGbind and the LGFE scores. This includes the precision of the experimental data itself as well as possible contributions associated with the compounds reaching their site of action. With mGluR5 PAMs, the site of action is in the transmembrane region, suggesting that interactions of the compounds with the membrane may contribute to their ability to access the binding site. Such processes can be impacted by the hydrophobicity of the compounds. While in the present study the inclusion of logP in the design strategy is used as a predictor of BBB crossing, it can also be used to determine if hydrophobicity makes a contribution to the obtained experimental results. ΔGbind was correlated with logP with an R2 ~ 0.24. Accordingly, a multiple regression analysis between ΔGbind and both LGFE and logP yielded good correlations with R2~0.33 and a PI of 0.45. Exclusion of 7 and 8 from this regression analysis yields an R2~0.47 and a PI of 0.57. Thus, the FragMaps were of utility with respect to both qualitatively directing ligand design they also yield a reasonable level of quantitative predictability in combination with hydrophobicity contributions.

With the narrow PAM binding site flanked by the transmembrane helices, and the planar geometry of 1 and its derivatives, two binding poses of the molecules were considered, as described above. Dichlorobenzenes, 21 and 22 have good overlap with the A2 FragMap density in the binding pose 1 leading to their favorable LGFE scoring compared to large polar substituents, such as 23, that corresponded to larger IC50 values. On the other hand, although 7 has a favorable LGFE score owing to good overlaps of the −N-CH3 modification of the ring with the A1 APOLAR affinities, this correlated poorly with its high IC50, indicating that the change in the ring structure impacts binding in a manner not adequately modeled. Compound 1 and some of its ortho- and meta-substituted derivatives, such as 2 and 19, scored comparably in both the poses, indicating that these ligands are likely to occupy the binding pockets in both possible orientations. Ligands 15, 16, 21 and 24 scored better in pose 1 than in pose 2, owing to poorer overlaps with the FragMap densities near A1. Improved structures of the mGluR5 TM region, versus the presently used homology models, are anticipated to further improve the predictability of the SILCS based modeling.

3. Conclusion

Acyl-2-aminobenzimidazole is a privileged scaffold that has found application in various therapeutic agents including inhibitors of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 (IRAK4)36, inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase,37 and anti-fungal agents38. Here Acyl-2-aminobenzimidazole derivatives inhibited LPS stimulated NO production, likely through actions at mGluR 5. Further structural optimization of Acyl-2-aminobenzimidazole may result in analogs with higher affinity and better clinical therapeutic properties.

4. Experimental section

All 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on spectrometers operating at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm, and coupling constants J are given in hertz. Proton chemical shifts are reported relative to residual solvent peak (CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm, CD3OD at 3.31 ppm, and DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm). The following abbreviations are used for signal multiplicity: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br = broad, quin = quintet, sept = septet, dt = doublet of triplets. Carbon chemical shifts are reported relative to solvent peaks (CDCl3 at 77.0 ppm and DMSO-d6 at 39.51 ppm). Column chromatography purifications were conducted on silica gel 60 Å (40−63 μm, Sorbent Technologies, catalog #40930). Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on glass sheets precoated with silica gel (60UV254, Sorbent Technologies, catalog −2115126), and visualized by UV light (λ = 254 nm), iodine (in silica gel), and/or phosphomolybdic acid (PAM, 10% in ethanol). Mass spectra were recorded using electrospray as the ionization technique. All reactions were run under an inert atmosphere (nitrogen) with oven-dried glassware using standard techniques. All reactions were stirred magnetically. DMF, DCM, CH3CN and THF were dried by LabContour Solvent Purification System. Commercial reagents were used as received unless otherwise specified. All new compounds have shown >95% purity based on NMR characterization.

4.1. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzamide (1)

To a mixture of benzoic acid (122 mg, 1.0 mmol), 1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-amine (133 mg, 1.0 mmol), TSTU (450 mg, 1.5 mmol), and DIPEA (260 μL, 1.5 mmol) was added DMF (4.0 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight and concentrated. To the residue was added CH2Cl2 (5.0 mL), followed by sonication for 2 min. The resulting yellow slurry was filtered and the solid was washed using DCM (3 × 10 mL) to give crude product, which was further purified by flash chromatography to yield compound 1 as a pale white solid (70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.14-7.16 (m, 2H), 7.46-7.48 (m, 2H), 7.52-7.62 (m, 2H), 7.60-7.62 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 8.15-8.17 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 12.27 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 113.8, 122.0, 128.7, 128.8, 134.8, 149.3, 168.8; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H12N3O 238.0, found 238.0.

4.2. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2–fluorobenzamide (2)

Compound 2 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.23 (m, 3H), 7.34 (m, 1H), 7.44 (m, 2H), 7.58 (m, 1H), 8.11 (m, 1H), 11.14 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 114.1, 116.6, 116.8, 121.9 (2C), 124.8, 130.8, 133.4, 133.5, 135.2, 148.1, 158.7, 161.2, 165.9; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11FN3O 256.0, found 256.0.

4.3. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2–chlorobenzamide (3)

Compound 3 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (62%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.11-7.14 (m, 2H), 7.41-7.45 (m, 3H), 7.48-7.55 (m, 2H), 7.64-7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 12.37 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 114.3, 121.9, 127.6, 129.8, 130.2, 130.7, 131.9, 135.7, 136.2, 147.6, 167.6; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11ClN3O 272.0, found 272.0.

4.4. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (4)

Compound 4 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (61%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.13-7.14 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 7.46-7.47 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 7.71-7.85 (m, 4H), 12.38 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 114.1, 122.0 (2C), 126.8, 129.4 (2C), 130.8 (2C), 132.9 (2C), 135.2, 136.1, 148.1, 168.9; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H11F3N3O 306.0, found 306.0.

4.5. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)picolinamide (5)

Compound 5 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (54%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.09-7.11 (m, 2H), 7.46-7.48 (m, 2H), 7.69-7.72 (m, 1H), 8.06-8.10 (m, 1H), 8.21 (m, 1H), 8.72-8.74 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 112.8, 121.7, 122.6 (2C), 122.8 (2C), 131.8, 144.1, 150.6 (2C), 150.9, 151.7, 170.2; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C13H11N4O 239.0, found 239.0.

4.6. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-chlorobenzamide (6)

Compound 6 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.16-7.18 (m, 2H), 7.45-7.47 (m, 2H), 7.52-7.55 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.62-7.63 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.10-8.12 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 12.45 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 112.8, 122.2, 127.2, 128.3, 130.4, 131.4, 132.4, 133.2, 138.3, 150.8, 169.2; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11ClN3O 272.0, found 272.0.

4.7. 3-Chloro-N-(1-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzamide (7)

Compound 7 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.78 (br s, 1H), 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.41-7.57 (m, 5H), 7.25-7.29 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 173.9, 152.0, 139.1, 130.3, 130.0, 129.8, 128.7, 126.7, 122.8, 112.1, 109.6, 28.3. ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H13ClN3O 286.0, found 286.0.

4.8. N-(Benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-chlorobenzamide (8)

Compound 8 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (70%).. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.97 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (dd, J = 19.4, 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (dd, J = 14.6, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.1, 158.1, 134.6, 132.5, 130.7, 130.2, 129.9, 127.7, 126.6, 124.2, 122.2, 121.13. ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H10N2OS 255.0, found 255.0.

4.9. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (9)

Compound 9 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (67%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.61 (br s, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.39-7.42 (d, J = 7.2, 1H), 7.93-7.95 (d, J = 7.2, 2H), 7.74-7.78 (m, 1H), 7.45 (s, 2H), 7.19 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ. 112.8, 122.7, 125.3, 128.3, 130.0, 132.0, 132.7, 138.0, 151.7, 170.0; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H11F3N3O 306.0, found 306.0.

4.10. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3–nitrobenzamide (10)

Compound 10 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (56%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.19-7.21 (m, 2H), 7.43-7.45 (m, 2H), 7.77-7.81 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.38-8.40 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.54-8.56 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 8.97 (s, 1H), 12.63 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 112.4, 122.9, 123.5, 126.1, 130.3, 130.9, 135.0, 139.3, 148.1, 152.6, 170.3; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11N4O3 283.0, found 283.0.

4.11. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3–methoxybenzamide (11)

Compound 11 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (73%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.85 (s, 3H), 7.13-7.17 (m, 3H), 7.45 (m, 3H), 7.70 (s, 2H), 12.25 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 55.7, 113.4, 113.8, 118.5, 121.1, 121.9, 129.9, 134.9, 136.1, 149.2, 159.6, 168.3; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H13N3O2 268.0, found 268.0.

4.12. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-4-fluorobenzamide (12)

Compound 12 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.13 (m, 2H), 7.34 (m, 2H), 7.44 (m, 2H), 8.22 (m, 2H), 11.25 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ113.4 (2C), 115.8 (2C), 122.1, 131.4 (2C), 132.0, 133.9, 150.0, 163.5, 165.9, 168.6; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11FN3O 256, found 256.0.

4.13. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-4–chlorobenzamide (13)

Compound 13 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (57%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.14-7.16 (m, 2H), 7.44-7.46 (m, 2H), 7.58-7.56 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 8.14-8.16 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 12.50 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 113.2, 122.3, 128.7, 130.7, 133.3, 134.8, 137.0, 150.6, 169.3; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11ClN3O 272.0, found 272.0.

4.14. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl) benzamide (14)

Compound 14 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (62%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.18 (s, 2H), 7.50 (s, 2H), 7.86 (s, 2H), 8.37 (s, 2H), 12.59 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 112.9, 122.6, 125.6, 126.1, 129.6, 130.5, 131.4, 132.1, 135.0, 140.6, 151.5, 166.6, 170.1; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H11F3N3O 306.0, found 306.0.

4.15. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-4-nitrobenzamide (15)

Compound 15 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.19-7.21 (m, 2H), 7.43-7.45 (m, 2H), 7.77-7.81 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.38-8.40 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.54-8.56 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 8.97 (s, 1H), 12.63 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 112.4, 122.9, 123.5, 126.1, 130.3, 130.9, 135.0, 139.3, 148.1, 152.6, 170.3; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H11N4O3 283.0, found 283.0.

4.16. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-4-methoxybenzamide (16)

Compound 16 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (57%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.05-7.07 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (m, 2H), 7.45 (m, 2H), 8.12-8.14 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 12.18 (br s 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 55.8, 113.9 (2C), 114.1 (2C), 121.6 (2C), 130.7 (2C), 135.5, 162.8, 167.4; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H13N3O2 268.0, found 268.0.

4.17. N-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)nicotinamide (17)

Compound 17 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (61%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.25 (br s, 2H), 8.75-8.74 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.01-7.99 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 7.45-7.44 (m, 2H), 7.20-7.19 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 170.2, 151.7, 150.9, 144.1, 131.8, 122.8, 122.6, 112.8. ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C13H11N4O 239.0, found 239.0.

4.18. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-(dimethylamino)benzamide (18)

Compound 18 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (64%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.98 (s, 6H), 6.93-6.95 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11-7.12 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.39-7.41 (m, 2H), 7.48 ( m, 3H), 12.19 ( s, 2H ); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 39.3, 112.0, 114.2, 116.4, 121.7, 129.4, 134.5, 148.4, 150.7, 168.1; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C16H17N4O 281.1, found 281.1.

4.19. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2,5-dichlorobenzamide (19)

Compound 16 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (62%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.46-7.47 (m, 2H), 7.59 (s, 2H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 12.4 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 110.5, 113.9, 119.2, 122.2, 124.3, 126.4, 129.6, 129.7, 131.4, 132.0, 134.4, 138.4, 148.6, 167.6; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H10Cl2N3O 306.0, found 306.0.

4.20. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2,5-di-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide 20

Compound 20 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.24(s, 1H), 8.07(s, 2H), 7.45-7.47(m, 2H), 7.17-7.19(m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 169.7, 150.0, 143.3, 139.0, 132.9, 128.3, 127.2, 126.8, 126.6, 125.0, 122.6, 119.3, 113.4, 110.4. ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C16H10F6N3O 374.0, found 374.0.

4.21. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3,4-dichlorobenzamide (21)

Compound 21 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.28-7.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.59-7.61 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.98 (s, 2H), 8.68 (s, 2H), 12.83 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 125.3, 125.5, 129.1, 130.9, 136.9, 137.3, 153.9, 167.6; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H10Cl2N3O 306.0, found 306.0.

4.22. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3,5-dichlorobenzamide (22)

Compound 22 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (69%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.19-7.21 (m, 2H), 7.45-7.43 (m, 2H), 7.80 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 2H), 12.58 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 112.5, 123.0, 127.5, 130.8, 134.5, 141.2, 152.4, 169.5; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H10Cl2N3O 306.0, found 306.0.

4.23. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-methoxy-4-sulfamoylbenzamide (23)

Compound 23 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (63%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.01 (s, 3H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.22 (s, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (m, 1H), 7.84 (m, 1H), 7.90 (s, 1H), 12.46 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 56.6, 112.4 (2C), 113.3, 120.4 (2C), 122.3 (2C), 128.0, 133.2, 134.0, 140.8, 150.4, 156.2, 168.9, ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H15N4O4 347.0, found 347.0.

4.24. (E)-N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamide (24)

Compound 24 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.03-7.10 (m, 3H), 7.47-7.52 (m, 3H), 7.80-7.75 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 8.05-80.6 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.85 (s, H), 11.87 (br s, 1H), 12.16 (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 121.6 (2C), 123.1, 124.6 (2C), 130.7, 134.7 (2C), 139.1, 147.1, 149.9 (2C), 151.3 (2C), 164.4; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C15H13N4O 265.0, found 265.0.

4.25. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)cyclohexanecarboxamide (25)

Compound 25 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (66%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1,21 (m, 4H), 1.60 (m, 2H), 1.78 (m, 2H), 1,92 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 2.55 (m, 1H), 7.20 (m, 2H), 7.56 (m, 2H), 11.27 (br s, 1H), 12.30 (br s,1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.5, 25.8, 29.3, 44.2, 111.9, 127.3, 121.3, 147.2, 175.9; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C14H18N3O 244.1, found 244.1.

4.26. N-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)cyclobutanecarboxamide (26)

Compound 26 was synthesized using a similar procedure described for compound 1 (60%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.85 (m, 1H), 1.97 (m, 1H), 2.14 (m, 2H), 2.26 (m, 2H), 3.39 (m, 1H), 7.06 (s, 2H), 7.42 (s, 2H) 11.35 (br s, 1H), 12.05 (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.9, , 29.6, 45.3, 116.0, 121.0, 126.0, 151.1, 179.1; ESMS (M + H+) calcd for C12H14N3O 216.0, found 216.0.

5. Computer-aided Drug Design

5.1. Protein Preparation

Homology modeling of TM region of the LBD of mGluR5 was performed using MODELLER39 using the crystal structure of mGluR1 (PDB:4OR2)29 as the template. Residues P580-K828 of mGluR5 were aligned with S593-A840 of mGluR1. A total of 200 models were generated and ranked using the Discrete Optimized Protein Energy (DOPE) method40 and the highest ranking model was using as the starting structure for the SILCS simulations. The TM region of the mGluR5 model was inserted into a rectangular POPC membrane containing ~90 lipids with 10% cholesterol using the CHARMM-GUI41; the remainder of the system was filled with ~0.15 M NaCl aqueous solution based on the TIP3P water model42 to neutralize the system. Subsequent calculations were performed with CHARMM using the CHARMM36 protein and lipid force field. 3000 steps of minimization were run to remove bad contacts: of these 1500 steps were with SD43 and the remainder with adopted basis Newton-Raphson (ABNR) algorithms44. During minimization, positions of the protein backbone were harmonically restrained using a force constant of 10 kcal/mol/Å2 on the non-hydrogen atoms while the side chain non-hydrogen atoms were restrained with a force constant of 5 kcal/mol/Å2. Influx of water molecules into the hydrophobic core of the TM region was prevented using a harmonic restraining potential of 2.5 kcal/mol/Å along the x,y planes at a +/−11 Å of the z axis from the center of the receptor. The same force was also used to keep the heads and tails of the lipids in place, and configurations of the lipids were maintained with harmonic dihedral restraints with a force constant of 250 kcal/mol/rad2. The same restraints were used during the 375 ps of equilibration with a 1 fs time-step, but the restraint forces were gradually reduced as described previously.45 The first 50ps of equilibration was performed using Langevin dynamics with a friction coefficient of 3 ps−1. The remaining 325 ps of the equilibration used constant pressure-temperature (NPT) dynamics using the Langevin Piston integrator46. Covalent bonds involving hydrogens were fixed at the equilibrium length by the SHAKE algorithm47. Lennard-Jones (LJ) interactions were smoothed from 10 to 12 Å by a force switching function and the non-bonded pair list was generated out to 14 Å and updated heuristically. Electrostatic interactions were calculated by the particle-mesh Ewald48 summation method with a real space cutoff of 12 Å.

To the equilibrated system, the solutes, each at 0.25 M were added. The system was again minimized for an additional 1000 steps with the SD43 algorithm. A short equilibration was performed for 250 ps using the leapfrog version of the Verlet integrator.49 This phase of minimization and equilibration in the presence of the SILCS solutes was performed in GROMACS50, with the same CHARMM force fields51,52 as described above; and applying harmonic potential restraints with a force constant of 2.4 kcal/mol/Å2 on the protein non-hydrogen atoms. As detailed previously31,53, to prevent aggregation/ion pairing of hydrophobic and charged solutes, thereby promoting faster convergence, a repulsive energy term was introduced only between benzene:benzene, benzene:propane, propane:propane, acetate:acetate, acetate:methylammonium, and methylammonium:methylammonium molecular pairs. This was achieved by adding a massless particle to the center of mass of benzene and the central carbon of propane, acetate, and methylammonium. Each such particle does not interact with any other atom in the system but with other particles on the hydrophobic or charged molecules through the Lennard-Jones (LJ) force field term with parameters (ε = 0.01 kcal/mol; Rmin =12.0 Å).

5.2. SILCS-GCMC/MD

Ten GCMC/MD simulations were run 33. Each of these 10 simulations constituted 100 cycles of GCMC and MD, with each cycle involving 100,000 steps of GCMC and 0.5 ns of MD, yielding a cumulative 100 million steps of GCMC and 500 ns of MD over the 10 simulations. The GCMC procedure is described in detail in our previous work33. During GCMC, solutes and water are exchanged between their gas-phase reservoirs and a cubic region with 20 Å per side encompassing the PAM binding pocket of the mGluR5. The excess chemical potential (μex) supplied to drive fragment exchanges is periodically fluctuated over every 3 cycles, such that the average μex over the 100 cycles is approximately close to the hydration free energies as described before 33. The configuration at the end of the GCMC is used as the starting configuration in the MD. Before the production, a 500 step SD minimization and a 100 ps equilibration is run as described above for the protein preparation simulations. Production runs were performed with the leapfrog integrator with a time step of 2 fs. The Nose−Hoover method 54,55 was used to maintain the temperature at 298 K with the protein and the remainder of the system separately coupled to the heat bath. Pressure was maintained at 1 bar using the Parrinello−Rahman 56 barostat. The time constant used for temperature and pressure coupling was uniformly 1 ps. The LINCS 57 algorithm was used to constrain water geometries and all covalent bonds involving a hydrogen atom. vdW interactions were switched off smoothly in the range of 10±12 Å, and the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method 48 was used to treat long-range electrostatics with a real space cut off of 12 Å, with the order of B-spline interpolation set to 4 and the maximum grid spacing set to be 1.2 Å. Long-range dispersion correction to the energy and pressure was applied. Weak restraints were applied only on the backbone Cα carbon atoms with a force constant (k in 1/2 kδx2) of 0.12 kcal/mol/Å. This was done to prevent the rotation of the protein in the simulation box and potential denaturation due to the presence of small molecules in the aqueous solution. The last conformation from the production MD is used as the starting conformation of the next GCMC cycle.

6. Microglial Cell Cultures, Drugs Treatment, Nitric Oxide, and Cell Viability Assay

The immortalized murine BV2 microglial cells were grown and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The potency of compounds 1-26 as PAMs of mGluR5 was evaluated by the NO assay following the NO production using the Griess Reagent Assay (Invitrogen). All compounds reconstituted in 0.02% dimethylsulfoxide (final concentration) was applied to microglia for 1 h before lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 50 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) stimulation. After 24 h incubation with the compounds and LPS, the nitrite in the culture supernatant was measured as an indicator of nitric oxide production using the Griess reagent assay (G7921, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability was measured using the CytoTox96 NonRadioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. We used CHPG as the positive control for inhibition of NO production as previously described.18

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UMB Pilot & Exploratory Interdisciplinary Research (IDR), NIH grant CA107331 and Maryland Industrial Partnerships Award 5212. The authors acknowledge computer time and resources from the Computer Aided Drug Design (CADD) Center at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: ADM Jr., is cofounder and CSO of SilcsBio LLC.

References

- 1.Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, McCrea M, Cantu RC, Randolph C, Jordan BD. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:719. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/57.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panter SS, Faden AI. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;136:165. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90040-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popovich PG, Guan Z, McGaughy V, Fisher L, Hickey WF, Basso DM. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002;61:623. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.7.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keane RW, Davis AR, Dietrich WD. J. Neurotrauma. 2006;23:335. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hausmann ON. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:369. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall ED, Springer JE. NeuroRx. 2004;1:80. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Prog. Brain Res. 2007;161:125. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)61009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl) 2002;103:607. doi: 10.1007/s00401-001-0510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spranger M, Fontana A. Neuroscientist. 1996;2:293. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilhardt F. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:17. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Gan WB. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:752. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aloisi F. Glia. 2001;36:165. doi: 10.1002/glia.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrnes KR, Loane DJ, Stoica BA, Zhang J, Faden AI. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebicke-Haerter PJ. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005;81:327. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrnes KR, Garay J, Di Giovanni S, De Biase A, Knoblach SM, Hoffman EP, Movsesyan V, Faden AI. Glia. 2006;53:420. doi: 10.1002/glia.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenzlinger PM, Hans VH, Joller-Jemelka HI, Trentz O, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Kossmann T. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:479. doi: 10.1089/089771501300227288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Biase A, Knoblach SM, Di Giovanni S, Fan C, Molon A, Hoffman EP, Faden AI. Physiol. Genomics. 2005;22:368. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00081.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loane DJ, Stoica BA, Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Byrnes KR, Faden AI. J Biol. Chem. 2009;284:15629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806139200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loane DJ, Stoica BA, Tchantchou F, Kumar A, Barrett JP, Akintola T, Xue F, Conn PJ, Faden AI. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11:857. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0298-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conn PJ, Pin J-P. Ann. Rev. Pharm. Tox. 1997;37:205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Brien JA, Lemaire W, Chen T-B, Chang RSL, Jacobson MA, Ha SN, Lindsley CW, Schaffhauser HJ, Sur C, Pettibone DJ, Conn PJ, Williams DL. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:731. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien JA, Lemaire W, Wittmann M, Jacobson MA, Ha SN, Wisnoski DD, Lindsley CW, Schaffhauser HJ, Rowe B, Sur C, Duggan ME, Pettibone DJ, Conn PJ, Williams DL. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;309:568. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Z, Wisnoski DD, O’Brien JA, Lemaire W, Williams Jr DL, Jacobson MA, Wittman M, Ha SN, Schaffhauser H, Sur C, Pettibone DJ, Duggan ME, Conn PJ, Hartman GD, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Letts. 2007;17:1386. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engers DW, Rodriguez AL, Williams R, Hammond AS, Venable D, Oluwatola O, Sulikowski GA, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:505. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma S, Kedrowski J, Rook JM, Smith RL, Jones CK, Rodriguez AL, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4103. doi: 10.1021/jm900654c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritzén A, Sindet R, Hentzer M, Svendsen N, Brodbeck RM, Bundgaard C. Bioorg. Med. Chem.Lett. 2009;19:3275. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez AL, Grier MD, Jones CK, Herman EJ, Kane AS, Smith RL, Williams R, Zhou Y, Marlo JE, Days EL, Blatt TN, Jadhav S, Menon UN, Vinson PN, Rook JM, Stauffer SR, Niswender CM, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD, Conn PJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;78:1105. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue F, Stoica BA, Hanscom M, Kabadi SV, Faden AI. CNS & Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2014;13:558. doi: 10.2174/18715273113126660199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu H, Wang C, Gregory KJ, Han GW, Cho HP, Xia Y, Niswender CM, Katritch V, Meiler J, Cherezov V, Conn PJ. Science. 2014;344:58. doi: 10.1126/science.1249489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malherbe P, Kratochwil N, Zenner M-T, Piussi J, Diener C, Kratzeisen C, Fischer C, Porter RHP. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:823. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guvench O, MacKerell AD. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raman EP, Yu W, Lakkaraju SK, MacKerell AD., Jr J. Chem. Info. Model. 2013;53:3384. doi: 10.1021/ci4005628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakkaraju SK, Raman EP, Yu W, MacKerell AD. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014:10. doi: 10.1021/ct500201y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trott O, Olson AJ. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearlman DA, Charifson PS. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:3417. doi: 10.1021/jm0100279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powers JP, Li S, Jaen JC, Liu J, Walker NP, Wang Z, Wesche H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:2842. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JH, An MH, Choi EH, Choo HYP, Han G. Heterocycles. 2006;70:571. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilyugin VS, Sapozhnikov YE, Sapozhnikova NA. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2004;74:738. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiser A, Do RKG, Šali A. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen M. y., Sali A. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2507. doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jo S, Lim JB, Klauda JB, Im W. Biophys. J. 2009;97:50. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durell SR, Brooks BR, Ben-Naim A. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:2198. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levitt M, Lifson S. J. Mol. Biol. 1969;46:269. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J. Comput. Chem. 1983;4:187. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shim J, Coop A, MacKerell AD. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feller SE, Zhang Y, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:4613. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allen MP, Tildesley DJ, Banavar JR. Phys. Today. 1989;42:105. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hess B, Kutzner C, Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:671. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PE, Mittal J, Feig M, MacKerell AD., Jr J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raman EP, Yu W, Guvench O, MacKerell AD., Jr J. Chem. Info. Model. 2011;51:877. doi: 10.1021/ci100462t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nosé S. Mol. Phys. 1984;52:255. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoover WG. Phys. Rev. A. 1985;31:1695. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parrinello M, Rahman A. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463. [Google Scholar]