Abstract

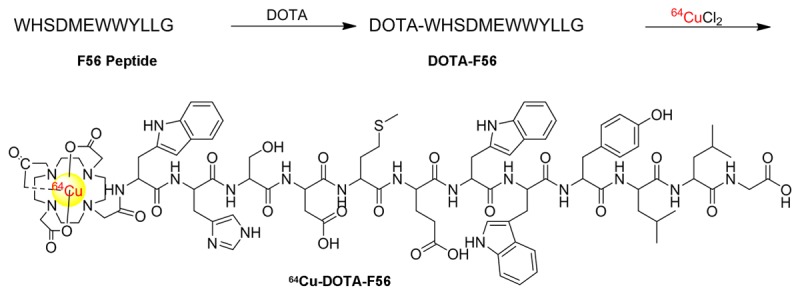

Noninvasive imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1) remains a great challenge in early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Here we reported the synthesis, radiolabeling, and evaluation of a novel 64Cu-radiolabeled peptide for noninvasive positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of VEGFR1 positive gastric cancer. The binding of modified peptide WHSDMEWWYLLG (termed as F56) to VEGER-1 expressed in gastric cancer cell BCG823 has been confirmed by immune-fluorescence overlap. DOTA-F56 was designed and prepared by solid-phase synthesis and folded in vitro. 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was synthesized in high radiochemical yield and high specific activity (S.A. up to 255.6 GBq/mmol). It has excellent in vitro stability. Micro-PET imaging of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 identifies tumor in BCG823 tumor-bearing mice, while that of 18F-FDG does not. Immunohistochemical analysis of excised BCG823 xenograft showed colocalization between the PET images and the staining of VEGFR1. These results demonstrated that 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide has potential as a noninvasive imaging agent in VEGFR1 positive tumors.

Keywords: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1, copper-64, gastric cancer, molecular imaging, F56 peptide

Introduction

Cancer is still one of the most threaten to human health. It was estimated that there are 14.1 million new cancer cases and 8.2 million cancer deaths occurred in 2012 worldwide [1]. Among all cancer types, 951,600 new gastric cancer cases and 723,100 deaths are estimated to have occurred and with highest incidence rates in Eastern Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, and South America. Due to the limited clinical symptoms, early detection of gastric cancer relies on opportunistic screening [2]. About 90% of gastric cancer patients were initially diagnosed in advanced stage, with 5-year survival rate less than 20%, even in developed Asian countries [2,3].

Early detection and treatment are critical to reduce morality from gastric cancer. Although researches on biotherapy, immunotherapy and gene therapy provide multi-dimensional treatments [4-6], the clinical results remain limited. In comparison, gastric cancer in early stage has excellent outcome from therapy, with five-year survival rate higher than 90%.

Noninvasive molecular imaging, especially PET, is becoming an effective method for diagnosis and staging of cancer, and monitoring of the efficiency of individual therapy [7]. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET has been gradually accepted by clinicians, especially for recurrent gastric cancer after surgical resection [8,9]. However, 18F-FDG has limited use due to its low sensitivity, with only about 50% detection rate in early gastric cancer [10].

There is still an urgent need of developing more sensitive and specific PET tracers for early detection of gastric cancer. Studies had revealed that elevated levels of VEGF-A, and its receptor, VEGFR1, were found in gastric cancer patients [11]. In addition, VEGFR1 overexpression in peripheral blood was associated with advanced clinical stage of the cancer [12]. VEGF and VEGFR1 provide legible targets for molecular imaging [13-15]. Up to now, several PET tracers targeting VEGFRs have been designed, and most of them mimic the natural/mutated VEGF isoforms [16-18], and others are antibodies with high renal uptake and high normal organs background [19-21]. However, these bulky antibodies are generally difficult and costly to prepare and may induce immune reaction in vivo. A dimeric 64Cu-DOTA-GU4OC4 peptoid was used to perform noninvasive PET detection of VEGFR2 [22]. In addition, the clinical imaging using 123I-VEGF165 in patients with gastrointestinal tumors and obtained 58% overall scan sensitivity [23,24]. Due to limited supply of 123I nuclide and high background in imaging, no further study was reported.

We previously discovered a novel VEGFR1-specific peptide, named as F56, through phage display screening with extracellular Ig-like domain I-IV of VEGFR1 fused with glutathione-S-transferase (GST) as target [25]. In vitro and in vivo studies show that F56 displaced VEGF binding to its receptor VEGFR1 and significantly inhibited tumor growth. The conjugates between F56 and multifunctional nanoparticles were developed to specifically target VEGFR1 in the molecular imaging of VEGFR1-expressing tumor xenograft in mice [26].

In this study, we aim to develop a novel F56-based PET tracer for the imaging of VEGFR-1 positive tumor. 64Cu (T1/2 = 12.7 h, β+ = 0.653 MeV; β- = 0.578 MeV) is an excellent nuclide which has characteristics for PET imaging and targeted radiotherapy of cancer. It can also be produced in large quantities and with high specific activity [27,28]. Here, we report the results of identifying 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide as a PET probe, including a variety of chemical and biological analysis, animal Micro-PET imaging, and immunohistochemistry studies.

Materials and methods

Materials

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sodium tartrate (NaAc), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) and 0.5 M diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), trifluoro-acetic acid (TFA), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and human serum albumin (HSA), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 64Cu (7.4 MBq/μL) was provided by China Isotope and Radiation Company (Beijing, China). FITC-F56 peptide (sequence: WHSDMEWWYLLG) was provided by China Peptides Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Radiochemical purity was examined with radioactive thin-layer chromatography scanner (Bioscan, IAR-2000, Washington DC, USA), and HPLC (Agilent, USA), using YMC-Pack ODS-A C 18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm) and the following gradient program: 0-10 min solvent B from 20% to 65%. The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min. Solvent A was 0.01% TFA water and solvent B was 0.01% TFA CH3CN. The radioactivity was measured using an automated gamma scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer, 1470-002, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

P53 mutant human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line BCG823 was provided by the Peking University Cancer Hospital (Beijing, China). This cell line was selected as a tumor model due to its adherent, poorly differentiated properties [29,30]. Nude mice (nu/nu, female, 5-6 weeks old) were from Vital River (Beijing, China). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) was from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). Fetal bovine serum was from Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA). Approximately 1 × 106 BCG823 cells suspended in 100 µl of PBS were implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice for Micro-PET imaging when tumors reached 0.1 cm3. The mice were kept under specific pathogen free conditions and were handled and maintained according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

To stain with F56 peptide, we generated a monoclonal antibody (manuscript in preparation) specific for a fragment of F56. An antibody (TA303515) against VEGFR1 was purchased from Origene Company (Rockville, MD, USA).

Chemistry and radiochemistry

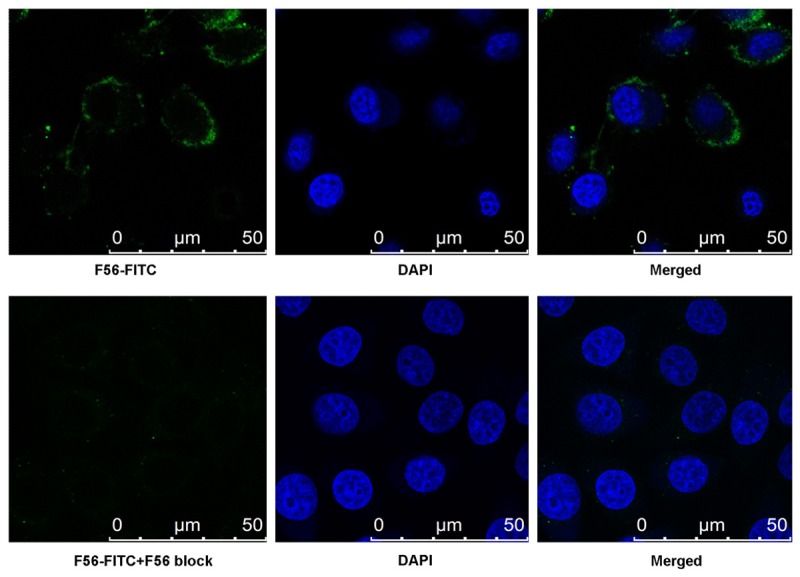

Fluorescence visualization of N-terminal modified FITC-F56 peptide

BGC823 cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated F56 peptide (10 μg/ml) for 30 min. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. The dye 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 5 ng/ml) was added to stain nuclei for 10 min and washed three times with PBS. Samples were observed under a TCS-SP2 confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany).

Synthesis of DOTA-F56 peptide

The DOTA-F56 peptide (amino acid sequence shown in Figure 1) was synthesized on a CS Bio CS336 instrument (Menlo park, CA) by Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide method. Briefly, Rink amide resin was swollen in DMF for 30 min. Fmoc groups were removed with 20% piperidine in DMF. Aliquots of amino acids (1 mM) were activated in a solution containing 1 mM of HOBt and 0.5 M DIC in DMF. During the synthesis, side-chain deprotection and resin cleavage were achieved by addition of a mixture of TFA/trimethylsilane/ethanedithiol/water (v/v, 94:2.5:2.5:1) for 2 h at room temperature. The crude product was precipitated with cold anhydrous diethyl ether and purified by a preparative RP-HPLC using a Varian Prostar instrument and Vydac C18 columns. Peptide purity was analyzed by analytical-scale RP-HPLC using a Vydac C18 column. DOTA-F56 peptide was further characterized by MADL-TOF-MS.

Figure 1.

The Synthetic strategy and radiolabeling of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide.

64Cu Radiolabeling of DOTA-F56

The radiolabeling of DOTA-F56 by 64Cu was performed as follows: each amount of DOTA-F56 (1-20 μg) was incubated with 222 MBq 64CuCl2 in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) for 30 min at 60°C (Figure 1). The reaction was monitored by Radio-HPLC and terminated with the addition of EDTA. 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was purified using a sep-pak C-18 column and eluted with 1.0 ml 80% ethanol. After the evaporation of ethanol by vacuum, the final product 64Cu-DOTA-F56 in water was passed through a 0.22 μm filter before further cell and animal experiments. The radiolabeling yield and radiochemical purity were determined by Radio-HPLC, > 99% respectively. The specific activity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was > 45 GBq/mmol (or 0.6 mCi/μg).

In vitro evaluation of 64Cu-DOTA-F56: Partition coefficient of 64Cu-DOTA-F56

The partition coefficient of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 complex was determined by measuring the distribution of radioactivity in equal volume of 1-octanol and 0.01 M PBS. Briefly, a 10 μl aqueous solution of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 in PBS was added to a vial containing 1.00 ml of 1-octanol and 0.99 ml of PBS. After 8 min vortexes, the vial was centrifuged for 5 min to ensure complete separation of layers. Then, 10 μl of each layer was pipetted into separate test tubes, to calculate log P = log (counts in octanol/counts in water).

In vitro stability test

The stability of the 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide was examined by measuring its radiochemical purity by performing Radio-HPLC at different time intervals after the incubation. Specifically, 64Cu-DOTA-F56 (3.7 MBq) was added to a test tube containing 1.0 ml of 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4), 0.1 M NaOAc (pH 5.5), or 5% HSA, respectively. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C with shaking in a thermo mixer. For PBS and NaOAc system, the radiochemical purity was measured directly at 30 min, 1 h, 3 h, and 18 h by Radio-HPLC. For 5% HSA system, 200 μl of solution was mixed with 200 μl of acetonitrile to precipitate the protein, and the supernatant was analyzed by Radio-HPLC.

Cell uptake and micro-PET imaging studies

Briefly, BCG823 cells were seeded at 2.0 × 105 per well onto 12-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were washed twice with serum-free medium and incubated with radiotracer (2 μCi per well, 74 kBq) in 400 μl of serum-free medium at 37°C. After desired time points (10 min, 30 min, 60 min and 120 min), cells were washed three times with cold PBS and lysed in 200 μl of 0.2 M NaOH. Radioactivity of the cells was counted using a PerkinElmer 1470 automatic γ-counter. Cell uptake data were expressed as the percentage of the applied radioactivity per total radioactive.

PET imaging on mice bearing BCG823 xenograft was performed on a micro-PET scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc.). The mice bearing BCG823 tumor were injected with 37 MBq of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 (1.5 μg), 18F-FDG, or 64CuCl2, respectively. At indicated time after injection, the mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and placed in the prone position, near the center of the field of view of micro-PET. The 10-min static scans were obtained, and the images were reconstructed by a two-dimensional ordered subsets expectation maximum (OSEM) algorithm. No back-ground correction was performed.

Hematoxylin eosin staining (HE) and immunohistochemistry of BGC823 xenografts

For HE staining, the BCG823 xenografts were dissect from mice and air-dried at 40°C before freezing and storage. Then the frozen tissue slices were washed by PBS, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to show different structures of the tissue.

For immunohistochemisty analysis, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed using standard histological procedures. In order to block internal peroxidase, the frozen tissue sections were dipped in 3% H2O2 solution at room temperature for 5 min. Next, sections were placed into 0.01% pronase at 40°C for 40 min for antigen retrieval, and cooled to room temperature. After washing by PBS, sections were washed by the DAKO blocking solution to block non-specific binding for 5 min. The sections were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber and washed by PBS. Then they are detected using the EnVisionTM Kit (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Yellow or brown granules in cytoplasm or karyon were considered as positive staining.

Statistical analysis

The statistical computations were performed using the Prism software program. In all experiments, P-value < 0.05 was identified as statistically significant by a student’s t-test.

Results

Binding of FITC-F56 to BGC823 cells

F56 peptide is an antagonist of VEGF in its binding with VEGFR1. To confirm the binding of N-terminal modified F56 peptide to VEGFR1 positive BGC823 cells in vitro, FITC-F56 was incubated with BGC823 cells. The positive staining of the conjugate was detected at the peripheral of the cells (Figure 2). Moreover, the fluorescent signal from the surface of cells significantly was reduced by incubation of the cells with excess unconjugated F56 peptide (100 times than FITC-F56), demonstrating the binding specificity of FITC-F56. The in vitro binding of the conjugate led us to believe that other N-terminal modified F56 peptides would remain their binding affinity for VEGFR1, and they have potential for further in vivo tumor imaging as described below.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence visualization of FITC-F56 binds to BGC823 cells. BGC823 cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml FITC-F56 peptide for 30 min, fixed, stained with 5 ng/ml DAPI (blue), and observed under a confocal microscopy. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Chemistry and radiochemistry

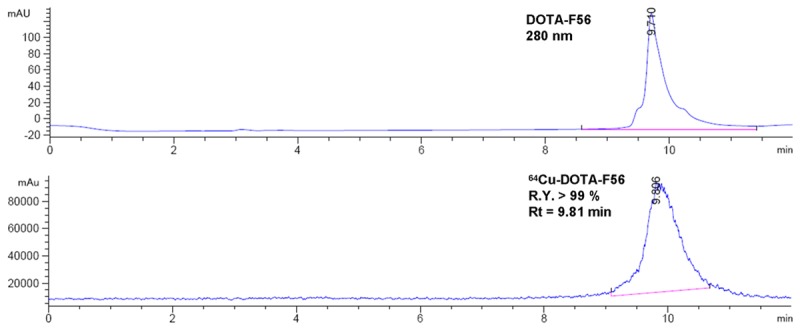

The conjugate DOTA-F56 was synthesized through conventional solid phase peptide synthesis and purified by semi-preparative HPLC. The purified peptide was generally obtained in about 20% yield. The retention time on analytical HPLC for DOTA-F56 was found with 98.6% chemical purity under 280 nm wavelength.

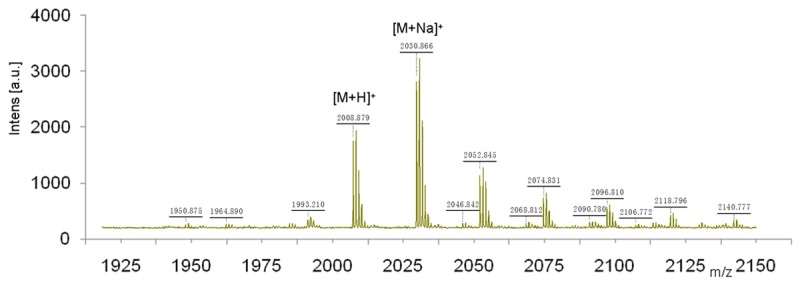

The purified DOTA-F56 was characterized by MALDI-TOF-MS and ESI-MS. The measured molecular weight was consistent with the expected molecular weight (M.W.) as calculated for C95H126N21O26S+ [M+H]+ = 2008.8898, found at 2008.879, calculated for C95H125N21NaO26S+ [M+Na]+ = 2030.8718, found at 2030.866. The main peak and relative isotope peaks were shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of DOTA-F56 peptide. The purified DOTA-F56 was characterized by MALDI-TOF-MS and the measured molecular weight was consistent with the expected molecular weight.

The radio labeled conjugate, 64Cu-DOTA-F56, was synthesized by the reaction of DOTA-F56 peptide with 64Cu2+ at 60°C after 30 min incubation. The labeling yield with 64Cu2+ was generally over 98%. After purification by C18 sep-pak column, the radio-chemical purity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was over 99% with the retention time at 9.81 min, which was slightly different from that of DOTA-F56 at 9.71 min (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

HPLC chromatographs of DOTA-F56 and 64Cu-DOTA-F56.

To increase the specific activity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56, the amount of DOTA-F56 used for the radiolabeling reaction was gradually reduced from 20 μg, 10 μg, 5 μg, 1 μg, to 0.5 μg, respectively, and the radioactivity of 64CuCl2 (222 MBq) remained the same under the same radiolabeling conditions. The radiolabeling yield decreased from 98% to 28%, and the Specific Activity (S.A.) increased from 22.50 GBq/mmol to 255.60 GBq/mmol, when the amount of DOTA-F56 was reduced from 20 μg to 0.5 μg (Table 1).

Table 1.

The actual specific activity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 under each condition

| DOTA-F56 (amount) | 20 μg | 10 μg | 5 μg | 1 μg | 0.5 μg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R.Y. (100%) | > 98% | > 98% | 96.2% | 36.9% | 28.4% |

| S.A. (GBq/mmol) | 22.50 | 45.00 | 86.58 | 166.05 | 255.60 |

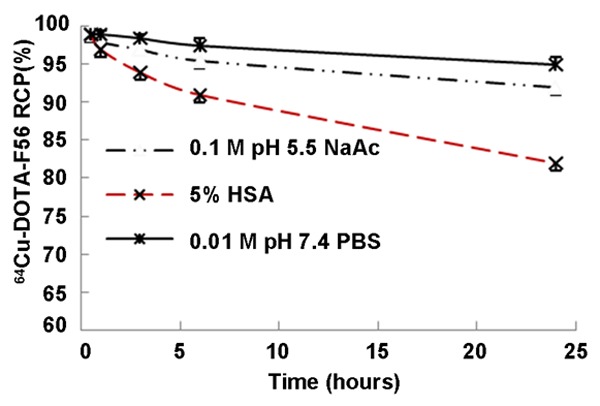

In vitro stability and LogP of 64Cu-DOTA-F56

There is more than 80% intact 64Cu-DOTA-F56 after 24 h of incubation in 3 conditions, 0.01 M PBS at pH 7.4, 0.1 M NaOAc at pH 5.5, and 5.0% HSA (Figure 5). 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide showed excellent in vitro stability in PBS and NaOAc at 37°C up to 24 h, and more than 90% of conjugates retained their original structures. It had excellent resistance to proteolysis and transchelation in 5.0% HSA with > 96% of the probe intact after a 3 h incubation and with > 80% after 24 h incubation, as monitored by Radio-HPLC with the Retention time of 9.81 min.

Figure 5.

In vitro stability of 64Cu-DOTA-F56. 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was mixed with 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4), 0.1 M NaOAc (pH 5.5), or 5% HSA, respectively. After incubation at 37°C with shaking in a thermo mixer, the radiochemical purity was measured by Radio-HPLC.

The log P value of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was determined to be 2.81 ± 0.12, indicating high lipophilicity of the radiolabeled peptide, from the octanol-water partition coefficient measurements.

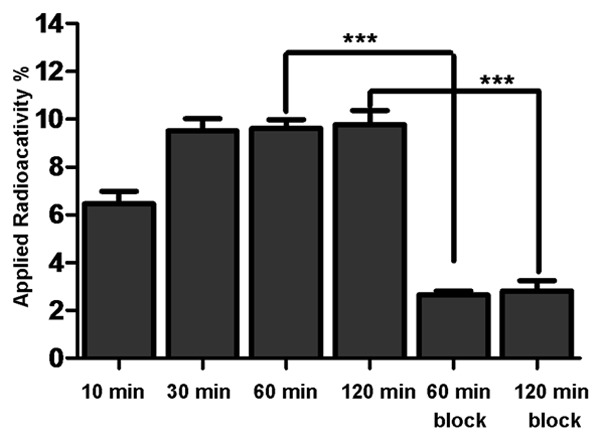

In vitro cell uptake assay

Cell uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 was evaluated using BCG823 cells, and the results are shown in Figure 6. The cell uptake values of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 at 10, 30, 60, and 120 min at 37°C were 6.5 ± 1.1%, 10.40 ± 1.3%, 9.6 ± 0.8%, and 9.8 ± 1.3%, respectively. While block groups values of 2.7 ± 0.3%, 2.8 ± 1.0% at 60 and 120 min were observed, respectively. A 4-fold greater accumulation of the probe occurred in cells incubated at 37°C compared with those block group, indicating that cell surface binding could be significantly inhibited by the presence of a large excess of F56 (P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

In vitro BCG-823 cell uptake assay. BCG823 cells were seeded in 12-well plate and incubated overnight. After incubation with radiotracer at 37°C for desired time points (10 min, 30 min, 60 min and 120 min), cells were washed and lysed. Radioactivity of the cells was counted using a PerkinElmer 1470 automatic γ-counter. Cell uptake data were expressed as the percentage of the applied radioactivity per total radioactive. ***P < 0.001 student’s t-test.

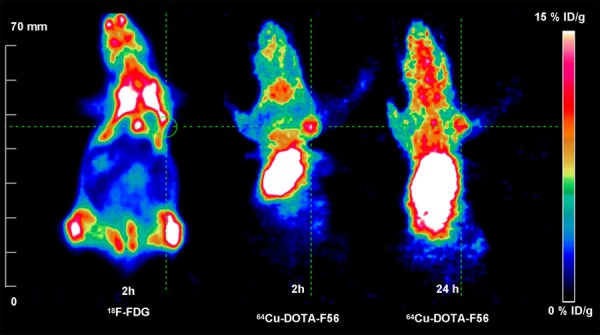

Micro-PET imaging study

The BCG823 tumor was clearly visible at 2 h after injection of 64Cu-DOTA-F56, better contrast images were showed at 24 h (Figure 7, decay-corrected coronal micro-PET images). The uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 in liver and kidney was relatively high, but it slowly decreased from 2 h to 24 h. Some radioactivity uptake was also observed in the region of thyroid, due to dissociation of 64Cu-DOTA-F56. For comparison, the tumor was barely visible on micro-PET imaging at 2 h after injection of 18F-FDG (Figure 7, decay-corrected coronal micro-PET images). When 37 MBq of 64CuCl2 was injected into the mice, micro-PET imaging indicated almost purely liver uptake, with no uptake in tumor. Semi-quantification analysis of Micro-PET images showed that the region of interest (ROI) value at tumor site was 4.7% ID/g and 8.0% ID/g at 2 h and 24 h post injection of 64Cu-DOTA-F56, while no specific binding was observed from 18F-FDG or 64CuCl2.

Figure 7.

Micro-PET imaging of a nu/nu mouse bearing BCG823 tumor cells. Images were obtained at 2 h PET imaging of 18F-FDG and 2 h, 24 h after injection of 64Cu-DOTA-F56. Static Micro-PET images are presented in 3D and the green line circles the tumors.

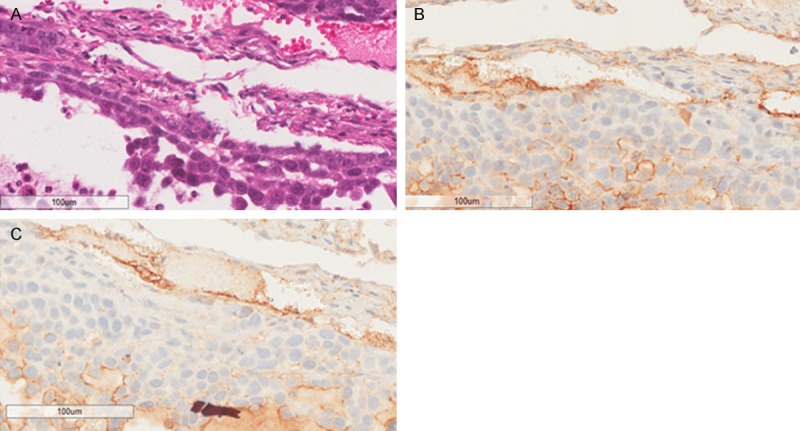

Immunohistochemistry study

Immunohistochemical stain studies were performed to demonstrate the binding specificity of F56 peptide with VEGFR-1 receptors. This was achieved through the comparison of the stainings of F56 peptide and VEGFR1 antibody. F56 peptide imaging showed no staining in regions of bleeding, light staining in regions of diffuse tumor cells, and heavy staining in regions of liquescence, which are believed to be the VEGFR-1 highly expression area (Figure 8A, 8B). The same pattern was observed by staining with VEGFR1 antibody (Figure 8A, 8C).

Figure 8.

HE and IHC stainings of tissue slides. A. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (HE stain); B. F56 peptide immunohistochemical staining; C. VEGFR1 immunohistochemical staining; Scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

We have confirmed that the binding of FITC-F56 peptide with VEGFR1 is comparable with that of F56 peptide by fluorescence imaging in BGC823 cells. We deduce that the N-terminal modified F56 is tolerable for binding with VEGFR1 receptor. This is also confirmed by our study of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 reported in this paper.

64Cu-DOTA-F56 was synthesized in a high radiochemical yield (> 98%) and radiochemical purity (> 99%), and its specific activity (22.5-255.6 GBq/mmol) is controllable through variation of the ratio between the 2 starting materials. The controllable SA may allow appropriate dose for gastric tumor therapy. 64Cu-DOTA-F56 showed lower lipophilicity as compared with F56 peptide, which is extremely insoluble in water or other aqueous media. The lipophilicity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56, as shown by log P of 2.81 ± 0.12, is in the right range for its tissue permeability.

Micro-PET imaging of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 showed excellent contrast images of the tumor having positive VEGFR1 positive expression in BCG823 tumor xenograft model were obtained at 2 h or 24 h after post the injection of 64Cu-DOTA-F56. In contrast, no accumulation of 18F-FDG was shown in tumor region by PET imaging. We also observed a prominent uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 in the tumor at 24 h after injection of 64Cu-DOTA-F56.

The micro-PET imaging by released 64Cu2+ was excluded by the Micro-PET studies of 64CuCl2. No uptake of radioactivity was observed in tumor (data not shown). It is also known that human copper transporter 1 (hCTR1) is the primary protein responsible for importing copper. It has been proved to be over expressed in non-small cell lung cancer, liver cancer and malignant melanomas [31,32]. However, no hCTR1 was expressed in malignant tissue of gastric carcinoma (0/29) [31]. No interference from free 64Cu2+ was observed, supporting the specific binding of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 in gastric cancer.

The receptor specificity of the probe was verified by the in vitro cell blocking experiment. Unlabeled F56 significantly reduced cell uptake both in fluorescence visualization and in vitro cell uptake test. In order to further verify the specificity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 in its binding affinity toward VEGFR1, we have studied immunohistochemical staining of F56 and VEGFR1 antibody. The staining pattern of the F56 peptide was similar to the distribution of VEGFR1 expression, allowing us to conclude that micro-PET images also reflected the expression of VEGFR1 in vivo.

The designed 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide could be useful for detection of early gastric cancer and other VEGFR1 positive tumors, and monitoring the efficacy of VEGFR1-based tumor treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of 64Cu-radiolabeled peptide which can bind to VEGFR1 for PET imaging. In addition, due to the inherent therapeutic effect of F56 peptide and 64Cu nuclide, 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide could also be used for VEGFR1-based peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT). Further research of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 as a therapeutic agent is still in progress.

Conclusion

We have successfully developed 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide targeted VEGFR1 for noninvasive molecular imaging of gastric tumor. It was synthesized in both high radiolabeling yield and controllable specific activity, and it showed excellent stability. Micro-PET imaging of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 showed clear images of tumors from 2 h to 24 h in nude mice bearing BCG823 cells, while no accumulation of 18F-FDG or 64CuCl2 was observed under the same conditions. The specificity of 64Cu-DOTA-F56 for VEGFR1 in vivo was deduced from the close match between stainings of F56 and that of VEGFR1. Overall, 64Cu-DOTA-F56 had high specific activity, high binding specificity, and gave excellent detection of gastric tumor as compared with 18F-FDG. 64Cu-DOTA-F56 peptide has potential for early detection of VEGFR1 positive gastric cancer, and potentially as a therapeutic agent.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Project on Drug Research and Development for the 12th Five-Year Plan of China (2012ZX09103301-013), the National 973 Program of China (2015CB553906), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81172083, 81371592, 81401467, 81301966, 81571705), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7132040, 7154188).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, Kim JJ, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Wu KC, Wu DC, Sollano J, Kachintorn U, Gotoda T, Lin JT, You WC, Ng EK, Sung JJ. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu M, Zheng HC, Xia P, Takahashi H, Masuda S, Takano Y, Xu HM. Comparison in pathological behaviours & prognosis of gastric cancers from general hospitals between China & Japan. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shou CC, Wu AW. [Application of biotherapy in recurrent or metastatic gastric cancer] . Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;14:569–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsueda S, Graham DY. Immunotherapy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1657–1666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalighinejad N, Hariri H, Behnamfar O, Yousefi A, Momeni A. Adenoviral gene therapy in gastric cancer: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:180–184. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey DL, Townsend DW, Valk PE, Maisey MN. Positron Emission Tomography: Basic Sciences. Secaucus, NJ: Springer-Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopkins S, Yang GY. FDG PET imaging in the staging and management of gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2:39–44. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshioka T, Yamaguchi K, Kubota K, Saginoya T, Yamazaki T, Ido T, Yamaura G, Takahashi H, Fukuda H, Kanamaru R. Evaluation of 18FFDG PET in patients with advanced, metastatic, or recurrent gastric cancer. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:690–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yun M, Lim JS, Noh SH, Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Bong JK, Cho A, Lee JD. Lymph node staging of gastric cancer using (18)F-FDG PET: a comparison study with CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1582–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Moundhri MS, Al-Shukaili A, Al-Nabhani M, Al-Bahrani B, Burney IA, Rizivi A, Ganguly SS. Measurement of circulating levels of VEGFA, -C, and -D and their receptors, VEGFR-1 and -2 in gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3879–3883. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosaka Y, Mimori K, Fukagawa T, Ishikawa K, Etoh T, Katai H, Sano T, Watanabe M, Sasako M, Mori M. Identification of the high-risk group for metastasis of gastric cancer cases by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 overexpression in peripheral blood. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1723–1728. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breen EC. VEGF in biological control. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:1358–1367. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backer MV, Backer JM. Imaging key biomarkers of tumor angiogenesis. Theranostics. 2012;2:502–515. doi: 10.7150/thno.3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Backer MV, Levashova Z, Patel V, Jehning BT, Claffey K, Blankenberg FG, Backer JM. Molecular imaging of VEGF receptors in angiogenic vasculature with single-chain VEGF-based probes. Nat Med. 2007;13:504–509. doi: 10.1038/nm1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai W, Chen K, Mohamedali KA, Cao Q, Gambhir SS, Rosenblum MG, Chen X. PET of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:2048–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Cai W, Chen K, Li ZB, Kashefi A, He L, Chen X. A new PET tracer specific for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:2001–2010. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshimoto M, Kinuya S, Kawashima A, Nishii R, Yokoyama K, Kawai K. Radioiodinated VEGF to image tumor angiogenesis in a LS180 tumor xenograft model. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen K, Cai W, Li ZB, Wang H, Chen X. Quantitative PET imaging of VEGF receptor expression. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Hong H, Niu G, Valdovinos HF, Orbay H, Nayak TR, Chen X, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression with (61)Cu-labeled lysine-tagged VEGF121. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:3586–3594. doi: 10.1021/mp3005269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hao G, Hajibeigi A, Leon-Rodriguez LM, Oz OK, Sun X. Peptoid-based PET imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) expression. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;1:65–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Kienast O, Preitfellner J, Hamilton G, Kurtaran A, Pirich C, Angelberger P, Dudczak R. Imaging gastrointestinal tumours using vascular endothelial growth factor-165 (VEGF165) receptor scintigraphy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1274–1277. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Kienast O, Preitfellner J, Havlik E, Schima W, Traub-Weidinger T, Graf S, Beheshti M, Schmid M, Angelberger P, Dudczak R. Iodine-123-vascular endothelial growth factor-165 (123I-VEGF165). Biodistribution, safety and radiation dosimetry in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;48:198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An P, Lei H, Zhang J, Song S, He L, Jin G, Liu X, Wu J, Meng L, Liu M, Shou C. Suppression of tumor growth and metastasis by a VEGFR-1 antagonizing peptide identified from a phage display library. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:165–173. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunel FM, Lewis JD, Destito G, Steinmetz NF, Manchester M, Stuhlmann H, Dawson PE. Hydrazone ligation strategy to assemble multifunctional viral nanoparticles for cell imaging and tumor targeting. Nano Lett. 2010;10:1093–1097. doi: 10.1021/nl1002526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadas TJ, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Anderson CJ. Coordinating radiometals of copper, gallium, indium, yttrium, and zirconium for PET and SPECT imaging of disease. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2858–2902. doi: 10.1021/cr900325h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niccoli Asabella A, Cascini GL, Altini C, Paparella D, Notaristefano A, Rubini G. The copper radioisotopes: a systematic review with special interest to 64Cu. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:786463. doi: 10.1155/2014/786463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Li QF, Ou Yang GL, Li CY, Hong SG. Effects of tachyplesin on the morphology and ultrastructure of human gastric carcinoma cell line BGC-823. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:676–680. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong W, Tu S, Xie J, Sun P, Wu Y, Wang L. Frequent promoter hypermethylation and transcriptional downregulation of BTG4 gene in gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holzer AK, Varki NM, Le QT, Gibson MA, Naredi P, Howell SB. Expression of the human copper influx transporter 1 in normal and malignant human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1041–1049. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A6970.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin C, Liu H, Chen K, Hu X, Ma X, Lan X, Zhang Y, Cheng Z. Theranostics of malignant melanoma with 64CuCl2. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:812–817. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.133850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]