Abstract

Occipital neuralgia (ON) is characterized by lancinating pain and tenderness overlying the occipital nerves. Both steroid injections and pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) are used to treat ON, but few clinical trials have evaluated efficacy, and no study has compared treatments. We performed a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, comparative-effectiveness study in 81 participants with ON or migraine with occipital nerve tenderness whose aim was to determine which treatment is superior. Forty-two participants were randomized to receive local anesthetic and saline, and three 120 second cycles of PRF per targeted nerve, and 39 were randomized to receive local anesthetic mixed with deposteroid and 3 rounds of sham PRF. Patients, treating physicians, and evaluators were blinded to interventions. The PRF group experienced a greater reduction in the primary outcome measure, average occipital pain at 6 weeks (mean change from baseline −2.743 ± 2.487 vs −1.377 ± 1.970; P <0.001), than the steroid group, which persisted through the 6-month follow-up. Comparable benefits favoring PRF were obtained for worst occipital pain through 3 months (mean change from baseline−1.925 ± 3.204 vs−0.541 ± 2.644; P = 0.043), and average overall headache pain through 6 weeks (mean change from baseline −2.738 ± 2.753 vs −1.120 ± 2.1; P = 0.037). Adverse events were similar between groups, and few significant differences were noted for nonpain outcomes. We conclude that although PRF can provide greater pain relief for ON and migraine with occipital nerve tenderness than steroid injections, the superior analgesia may not be accompanied by comparable improvement on other outcome measures.

Keywords: Headache, Occipital neuralgia, Pulsed radiofrequency, Steroid injection

1. Introduction

Occipital neuralgia (ON) is defined as a paroxysmal, shooting or stabbing pain in the posterior part of the scalp, in the distribution of the greater, lesser, and/or third occipital nerves, sometimes accompanied by diminished sensation or dysesthesia in the affected area with tenderness over the involved nerve(s), which responds to local anesthetic nerve blocks.28 There have been no epidemiological studies evaluating the prevalence of ON, as identified by response to injections.19 One retrospective review of 800,000 medical records in the Netherlands identified 30 cases, although this study likely underestimated the prevalence rate, as nondebilitating occipital headaches often go unreported, are self-treated, or are misdiagnosed.35 ON is frequently associated with head trauma and whiplash injuries.15,19,40 In one study evaluating service members evacuated from Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom with headaches, 4.9% were given a primary diagnosis of ON.15 However, these statistics may belie the socioeconomic burden of conditions that may respond to interventions targeting the occipital nerve(s), as approximately 50% of migraineurs, 2,5,6,11,23,48 a majority of individuals with cluster headache, 2,4,23,37,45 and significant proportions of individuals with tension-type,8,48 posttraumatic,29,48 and cervicogenic headaches8,23,29 also respond to occipital nerve block.

There have been few studies evaluating treatments for ON. Studies evaluating occipital nerve blocks with steroids have generally reported transient (<1 month) benefit,2,5,37,45 with one study performed for cluster headaches and another that used local anesthetic with clonidine but not steroids, being placebo-controlled.4,43 Recently, pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) has generated substantial interest in the pain medicine and neuroscience communities as a possible treatment for neuropathic pain. The conceptual appeal of PRF is that it exerts analgesic effects without damaging neural architecture. 20,46 The mechanisms by which PRF exerts its effects are still being elucidated, but the principal one may be through induction of a low-intensity electrical field around sensory nerves, which results in decreased conduction in C- and A-delta fibers.13 Preclinical studies also suggest that enhancement of descending noradrenergic, serotonergic, and opioid inhibitory pathways, alterations in gene expression, and temporary suppression of excitatory neurotransmission may play a role in antinociception.13,25,38,54,59 Numerous preclinical3,44,53 and several placebo-controlled studies34,41,57 have demonstrated the efficacy of PRF for neuropathic pain. For ON, several uncontrolled studies have reported benefit,12,31,51,55,56 with one study suggesting that pulsed RF might provide longer term benefit than steroid injections.22 In a single-blind randomized study conducted in 30 patients with cervicogenic headache, Gabrhelik et al.22 found that steroid injections and PRF of the greater occipital nerve provided comparable relief at 3 months, but that the analgesic effect of PRF was greater at 9 months. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of PRF and steroid injections for ON in a double-blind, comparative-effectiveness study.

2. Methods

We performed a randomized, double-blind, comparative-effectiveness study comparing PRF to steroid injections. Approval for this study was granted by the Internal Review Boards at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Naval Hospital-San Diego, Womack Army Medical Center-Fort Bragg, Portsmouth Naval Hospital, Tripler Army Medical Center, District of Columbia and Boston Veteran’s Administration (VA) Hospitals, Drexel University, and all participants who provided informed consent. Participants were treated and followed between August 2012 and February 2015.

2.1. Participants and settings

The study sites consisted of 5 military academic treatment facilities, 2 VA hospitals, and 2 civilian teaching hospitals. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years; a diagnosis of ON based on International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), second edition, criteria,27 including paroxysmal stabbing pain in the distribution of the greater or lesser occipital nerve(s), tenderness over the affected nerve(s), and relief of pain for at least 3 hours after bupivacaine local anesthetic block of the affected nerve(s), or an ICHD-2 diagnosis of migraine with a predominance of occipital pain and occipital nerve tenderness that responded to local anesthetic blockade; ≥4/10 pain; failure to respond to previous therapy to include non-opioid analgesics; and headache frequency ≥10 days/month. Exclusion criteria included unstable medical or psychiatric condition, implanted cardiac pacemaker or defibrillator that could not be disabled, previous PRF treatment of any nerve, and non-ON or nonmigrainous headache.

2.2. Randomization and interventions

81 participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio by computer-generated randomization tables. Enrollment was done by an investigator physician. Allocation was performed by a research nurse in blocks of 18 at Walter Reed and Johns Hopkins and in blocks of between 4 and 12 at other institutions based on anticipated enrollment. Study group allocation was contained within double-sealed envelopes, one of which was divulged after needle placement occurred before treatment. Suballocation was based on the presence or absence of concomitant migraine, which resulted in similar numbers of participants with ON-only and migraine with occipital nerve tenderness in each group. The research nurse, treating physician, and evaluating physician were blinded to treatment assignment.

2.3. Diagnostic blocks

In patients who presented or were referred for the study with clearly documented ON or migraine with occipital nerve tenderness that responded to diagnostic injections (n = 5), diagnostic blocks were not repeated. In those individuals who had not undergone diagnostic blocks or in whom definitive documentation was unavailable, these were performed with 3 mL of a solution containing bupivacaine 0.5% with or without (n = 5) steroid, per targeted nerve. In the recovery area, all patients were instructed on how to complete their 0 to 10 numerical rating scale (NRS) pain diaries every 30 minutes for 6 hours. All enrolled patients obtained ≥50% pain relief lasting at least 3 hours.

2.4. Treatments

All procedures were performed with the patient positioned prone, with the target sites marked out using anatomical landmarks and the area(s) of maximal tenderness. Light sedation was used in over 80% of cases. The technique was standardized via a video conference before initiation of the trial. In general, the typical target point for the greater occipital nerve was found to be one-quarter to one-third of the distance along a line connecting the external occipital protuberans to the mastoid process (generally 1.5–3 cm lateral to midline), and medial to the artery in a slight depression at the level of the superior nuchal ridge. For the lesser occipital nerve, the anticipated target point was located approximately 5 cm lateral to midline and slightly inferior at the lower third of the ear (approximately two-thirds of the distance from the occipital protuberans to the center of the mastoid process), confirmed at the point of maximal tenderness. A subcutaneous skin wheal was raised using lidocaine 1%and a 25-gauge needle 1 to 2 cm caudal and medial to the target point. For each nerve, a 20-gauge radiofrequency needle with a 10-mm active tip was inserted in a cephalad-medial oblique (ie, 25°–45°) angle towards the demarcated target(s). Electrical stimulation was performed to elicit concordant symptoms in the distribution of the occipital nerve(s), with repeated needle adjustments made to maximize stimulation at the lowest possible voltage. This was accomplished at a mean voltage of≤0.3 in all but 9 cases. Once proper needle position was confirmed, the attending physician left the room, the envelope was opened, and the patient received one of 2 treatments.

2.4.1. Group 1

This group received a 2.75-mL injection containing 1 mL 0.5% bupivacaine, 1 mL 2% lidocaine, and 0.75 mL normal saline at each targeted nerve (up to 4). After 4 minutes, PRF treatment was initiated with an RF generator using the following parameters: voltage output 40 to 60 V; 2 Hz frequency; 20 ms pulses in a 1-second cycle, 120 second duration per cycle; impedance range between 150 and 400 Ω; and 42°C plateau temperature. Three cycles were performed, with slight adjustments of the electrodes (ie, 45° clockwise, then 45° counter-clockwise) made between cycles, as preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that multiple cycles may increase effectiveness.31,53

2.4.2. Group 2

This group received a 2.75-mL injection containing 1 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine, 1 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 0.75 mL of 40 mg/mL depomethylprednisolone at each nerve. After 4 minutes, the same procedure was followed as for group 1 including the cannula adjustments in between shamcycles, except the RF generator was not activated. Steps to facilitate blinding included covering the participant’s head with sterile prep, use of sedation, waiting 4 minutes after local anesthetic was given before commencing treatment, decreasing the volume on the RF generator, and increasing the volume of music in the room during treatment. After the procedure, a generic note was entered into the medical record.

2.5. Co-interventions, outcome measures, follow-up, and missing data

Baseline data were recorded for the week before treatment. The data recorded during follow-up visits were the same as the baseline data except for medication reduction, which was predefined as cessation of a non-opioid analgesic or >20% reduction in opioid use14,18; satisfaction score; and posttraumatic stress disorder checklist–civilian version (PCL-C),58 which was only recorded before treatment. Contact between participants and the investigative team was prohibited during the study. Participants were given headache diaries after treatment in which their occipital and migraine pain scores could be recorded and were provided with instructions on how to taper their analgesic medications based on response. For those with persistent or increased pain, participants were instructed to either increase their baseline medications, or tramadol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed as rescue medications on an “as needed” basis; no other co-interventions were permitted. A telephone follow-up was performed 2 weeks after treatment in which the average and worst occipital and migraine pain scores were recorded. The first full follow-up visit was 6 weeks after treatment by an investigator blinded to treatment allocation. The primary outcome measure was predesignated to be the average 0 to 10 NRS occipital pain score at 6 weeks experienced during the week before follow-up, which was tabulated by patient report (n = 12) or headache diary (n = 69), if available. Secondary outcome measures included worst occipital pain score over the past week, average and worst overall headache/migraine pain scores in participants with migraine, frequency of severe (≥7/10) occipital and migraine headaches, days requiring rescue medications, satisfaction score on a 1 to 5 Likert scale (5 = very satisfied), Athens Insomnia Scale score,50 Short-Form Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) score (used to assess headache-related disability),36 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score,7 and a composite categorical outcome which was predefined as a ≥2-point decrease in average occipital headache score, coupled with a ≥4 score on the satisfaction scale and no increase in medication use.

In individuals who experienced a positive 6-week composite outcome, the next follow-up visit took place at 3 months. For ethical reasons, those with a negative outcome at interim follow-ups exited the study to receive nonstudy interventions, which is consistent with other randomized interventional studies.1,17,18,24 For these individuals, subsequent data points were imputed using the “last-observation-carried-forward” method.

2.6. Statistical analysis

This study was powered to determine whether PRF was superior to steroid injections. Using a 2-sided, 2-sample t test, it was determined that 38 patients in each group would be needed to have an 85% chance of detecting a difference between treatment groups of 1.1 point at their 6-week follow-up based on the following assumptions: mean starting NRS pain score in each group of 6.9; pulsed RF group will have a mean posttreatment score of 3.4 and the corticosteroid group will have a mean posttreatment score of 4.5; group standard deviations of 1.5; 10% dropout rate; alpha controlled at 0.05.

An intention-to-treat strategy was used for all analyses. Differences in treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals for pain and secondary outcome scores were calculated using χ2 and odds ratios for dichotomous variables, and t tests and Mann–Whitney for continuous variables, as indicated. A set of logistic regression models for categorical outcome at 6 weeks was created using variables hypothesized to have an effect on treatment (gender, migraine), as well as those found to have a P< 0.20 in univariate analysis (NOMREG function, SPSS). The final model was selected using Akaike Information Criteria.

3. Results

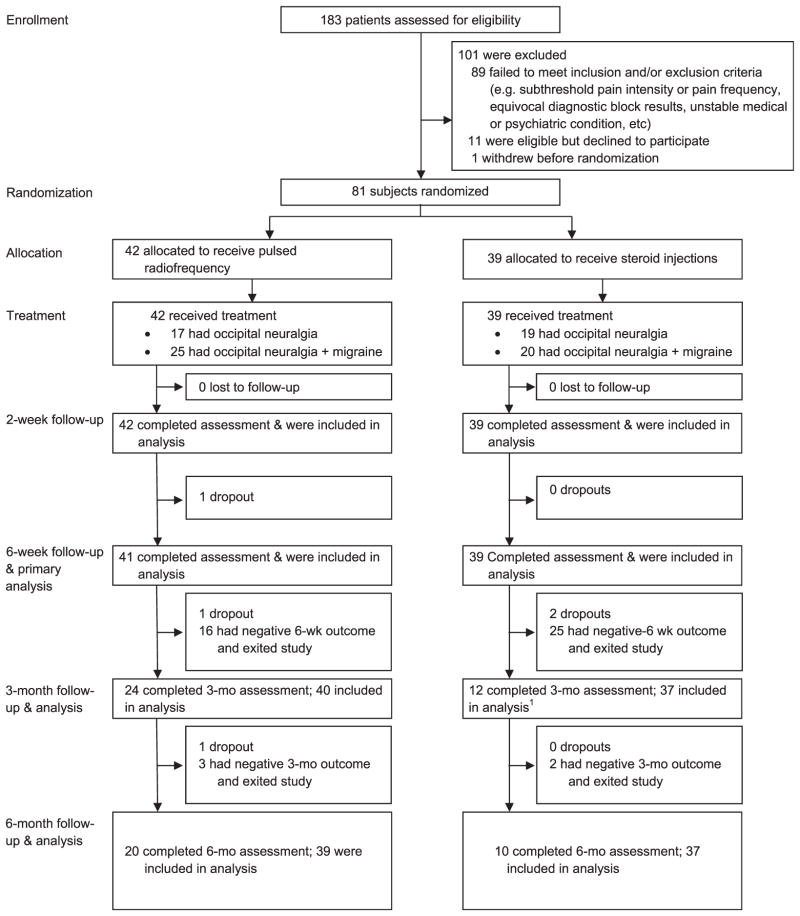

Among the 183 individuals screened at all study sites, 81 were randomized to receive either PRF or steroid injections. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups except that the PRF group experienced higher average occipital pain (5.77 vs 5.12, P = 0.047) and higher worst occipital pain when migraine was present (6.44 vs 5.56, P=0.044). The steroid group also had proportionally more participants whose headaches were deployment related (30.8% vs 11.9%, P < 0.038; Table 1; see Fig. 1 for progression of study participants).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by treatment group.

| Characteristic | Pulsed radiofrequency (n = 42) | Nerve blocks with steroids (n = 39) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 41.67 (10.72) | 41.08 (13.61) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 22 (52) | 21 (54) |

| Female | 20 (48) | 18 (46) |

| Duration of pain, mean (SD), y | 6.44 (7.39) | 5.36 (7.14) |

| Opioid therapy, n (%) | 10 (24) | 9 (23) |

| Active duty military, n (%) | 26 (63) | 21 (54) |

| Laterality, n (%) | ||

| Unilateral | 23 (55) | 17 (44) |

| Bilateral | 19 (45) | 22 (56) |

| Targeted nerves, n (%) | ||

| Greater occipital only | 21 (50) | 19 (49) |

| Lesser occipital only | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Greater and lesser occipital | 21 (50) | 20 (51) |

| Coexisting migraine, n (%) | 25 (60) | 20 (51) |

| Inciting event, n (%) | ||

| None | 19 (45) | 23 (59) |

| Motor vehicle collision | 6 (14) | 5 (13) |

| Fall | 4 (10) | 3 (8) |

| Battle-related injury | 5 (12) | 3 (8) |

| Other | 8 (19) | 5 (13) |

| Pain relief from diagnostic block, % | 74.69 | 78.12 |

| Deployment related, n (%) | 5 (12) | 12 (31) |

| Traumatic brain injury, n (%) | 8 (19) | 7 (18) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 6 (14) | 8 (21) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 10 (24) | 8 (21) |

| Allodynia, n (%) | 20 (48) | 22 (56) |

| Photophobia, n (%) | 28 (67) | 28 (72) |

| Phonophobia, n (%) | 26 (62) | 21 (54) |

| Coexisting pain condition, n | ||

| None | 10 | 12 |

| Low back pain | 16 | 15 |

| Neck pain | 7 | 9 |

| Arthralgia(s) | 1 | 1 |

| Neuropathic pain | 18 | 17 |

| Other | 2 | 2 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, n | ||

| None | 24 | 23 |

| Mood | 10 | 11 |

| Anxiety | 8 | 8 |

| Substance abuse | 1 | 0 |

| PTSD | 8 | 3 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Pretreatment migraine headache frequency, mean (SD)* | 2.17 (2.42) | 1.69 (2.09) |

| Pretreatment occipital neuralgia headache frequency, mean (SD)* | 3.18 (2.19) | 3.16 (2.50) |

| Pretreatment migraine rescue medication days, mean (SD)† | 3.82 (2.95) | 3.00 (2.65) |

| Pretreatment occipital neuralgia rescue medication days, mean (SD)† | 2.59 (2.93) | 2.61 (2.61) |

| Baseline headache impact test score | 65.02 (7.55) | 65.36 (6.40) |

| Baseline Athens insomnia scale score | 11.49 (5.52) | 9.46 (4.97) |

| Baseline posttraumatic stress disorder checklist score | 33.19 (17.05) | 29.97 (12.18) |

| Baseline beck depression inventory score | 12.81 (11.25) | 11.79 (9.23) |

Days per week with 0 to 10 pain scores ≥7/10.

Days per week requiring “rescue” analgesic medications.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart demonstrating progression of participants through study.

3.1. Outcomes

3.1.1. Headache intensity

Average and worst pain scores are shown in Table 2. For pain scores, the PRF group did better than the steroid group at all follow-ups, although the degree of pain relief diminished with time. For the primary outcome measure, average occipital pain at 6 weeks, PRF participants experienced a mean change from baseline of −2.743 ± 2.487, which favorably compared with those who received steroid injections (−1.377 ± 1.970; P = 0.008). The differences in average occipital pain (mean change from baseline −3.273 ± 2.368 in PRF participants vs −1.421 ± 2.062 in those who received steroids; P < 0.001) and worst occipital pain (−3.095 ± 2.701 vs −1.833 ± 2.540; P = 0.033) were present at 2 weeks, and persisted through 6 months for average occipital pain (mean change from baseline for the PRF group −1.413 ± 2.352 vs −0.33 ± 1.382; P = 0.017 in steroid participants). The difference in worst occipital pain favoring the PRF group was significant at 3 months (mean change from baseline −1.925 ± 3.204 vs −0.541 ± 2.644; P = 0.043), but not at 6 months (−1.263 ± 2.976 vs −0.149 ± 1.972; P = 0.083).

Table 2.

Pain score outcomes according to treatment group.*

| Pulsed radiofrequency group

|

Steroid injection group

|

Treatment comparison

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | Overall mean | Mean change from baseline | No. of patients | Overall mean | Mean change from baseline | Adjusted difference (95% CI)† | P | |

| Average occipital pain | ||||||||

| Baseline | 42 | 5.768 ± 1.337 | N/A | 39 | 5.115 ± 1.575 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 wk | 42 | 2.495 ± 2.094 | −3.273 ± 2.368 | 39 | 3.694 ± 2.221 | −1.421 ± 2.062 | −1.851 (−2.836 to −0.865) | <0.001 |

| 6 wk | 41 | 3.068 ± 2.431 | −2.743 ± 2.487 | 39 | 3.738 ± 2.415 | −1.377 ± 1.970 | −1.366 (−2.368 to −0.364) | 0.008 |

| 3 mo | 40 | 3.791 ± 2.573 | −1.890 ± 2.604 | 37 | 4.441 ± 2.237 | −0.654 ± 1.848 | −1.236 (−2.268 to −0.203) | 0.020 |

| 6 mo | 39 | 4.312 ± 2.232 | −1.413 ± 2.352 | 37 | 4.765 ± 1.998 | −0.330 ± 1.382 | −1.083 (−1.971 to −1.962) | 0.017 |

| Worst occipital pain | ||||||||

| Baseline | 42 | 7.821 ± 1.630 | N/A | 39 | 7.679 ± 1.558 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 wk | 42 | 4.726 ± 2.528 | −3.095 ± 2.701 | 39 | 5.846 ± 2.618 | −1.833 ± 2.540 | −1.262 (−2.421 to −0.113) | 0.033 |

| 6 wk | 41 | 5.354 ± 3.165 | −2.561 ± 3.279 | 39 | 6.064 ± 3.226 | −1.615 ± 2.964 | −0.946 (−2.339 to −0.442) | 0.181 |

| 3 mo | 40 | 5.850 ± 3.292 | −1.925 ± 3.204 | 37 | 7.149 ± 2.967 | −0.541 ± 2.644 | −1.384 (−2.724 to −0.048) | 0.043 |

| 6 mo | 39 | 6.705 ± 2.892 | −1.167 ± 2.952 | 37 | 7.541 ± 2.416 | −0.149 ± 1.972 | −1.018 (−2.172 to 0.136) | 0.083 |

| Average overall headache pain‡ | ||||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 6.440 ± 1.244 | N/A | 20 | 5.550 ± 1.638 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 wk | 25 | 3.392 ± 2.106 | −3.048 ± 2.605 | 20 | 4.220 ± 2.496 | −1.330 ± 1.922 | −1.718 (−3.127 to −0.309) | 0.018 |

| 6 wk | 24 | 3.678 ± 2.448 | −2.738 ± 2.753 | 20 | 4.410 ± 2.544 | −1.120 ± 2.100 | −1.618 (−3.133 to −1.035) | 0.037 |

| 3 mo | 24 | 4.000 ± 2.870 | −2.542 ± 3.287 | 18§ | 4.694 ± 2.480 | −0.917 ± 2.144 | −1.625 (−3.425 to 0.176) | 0.076 |

| 6 mo | 24 | 4.188 ± 2.637 | −2.354 ± 3.041 | 18§ | 4.861 ± 2.338 | −0.750 ± 2.116 | −1.604 (−3.298 to 0.089) | 0.063 |

| Worst overall headache pain‡ | ||||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 9.000 ± 0.816 | N/A | 20 | 8.500 ± 1.539 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 wk | 25 | 5.540 ± 2.669 | −3.460 ± 2.894 | 20 | 6.650 ± 2.744 | −1.850 ± 2.938 | −1.610 (−3.373 to 0.152) | 0.072 |

| 6 wk | 24 | 6.583 ± 3.202 | −2.458 ± 3.323 | 20 | 6.825 ± 3.109 | −1.675 ± 3.341 | −0.783 (−2.819 to 1.252) | 0.442 |

| 3 mo | 24 | 6.522 ± 3.232 | −2.565 ± 3.396 | 18§ | 7.417 ± 2.952 | −1.083 ± 2.861 | −1.482 (−3.502 to 0.538) | 0.146 |

| 6 mo | 24 | 6.761 ± 3.096 | −2.326 ± 3.322 | 18§ | 7.556 ± 2.623 | −0.944 ± 2.606 | −1.382 (−3.254 to 0.491) | 0.144 |

Plus–minus values are means ± SD. CI denotes confidence interval. 3-month and 6-month outcomes for those who exited the study because of treatment failure were imputed by ‘last observed outcome carried forward’. Numerical rating scores for pain are based on 0 to 10 numerical rating scales, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating severe pain.

Differences for pain scores were adjusted for baseline outcome values. Negative coefficients favor the pulsed radiofrequency group. Positive coefficients favor the steroid group.

Includes only those patients with migraine + occipital headaches.

Although the study was not powered to detect any subgroup differences, we separately analyzed the results in those participants with ON (n = 36) or migraine with occipital nerve tenderness (n = 45). In patients with ON without migraines, no significant differences were found between groups at any time point (mean change from baseline for average occipital pain at 6 weeks in the PRF group −1.779 ± 2.186 vs −1.667 ± 2.813 in the steroid group; P = 0.508).

In the subgroup with migraines, 20.0% (n = 9) reported auras, and 44.4% (n = 20) were diagnosed with chronic migraine. For average occipital pain in these patients, there was a significant difference in mean change from baseline at week 6 favoring the PRF group (mean change from baseline in the PRF group−3.426 ± 2.500 vs−1.438 ± 1.990 in the steroid group, P < 0.001), as well as at all other time points (−1.739 ± 2.540 vs −0.290 ± 1.548, P = 0.036 at 6 months). Significant changes favoring PRF treatment in migraineurs were noted for worst occipital pain at 2 weeks (data not shown) and 3 months (mean change from baseline −2.396 ± 3.633 vs −0.263 ± 2.306, P = 0.024), but not at 6 weeks or 6 months. For average overall headache severity, statistical significance was reached at 6 weeks (mean change from baseline in PRF group −2.738 ± 2.753 vs −1.120 ± 2.1; P = 0.037) but lost at 3 months (mean change from baseline in PRF group −2.542 ± 3.287 vs −0.917 ± 2.144 in the steroid group; P = 0.076). Regarding worst overall headache score, although all time points again favored the PRF group, the differences failed to reach statistical significance. No differences were noted in any outcome measures between those migraineurs diagnosed with chronic vs episodic migraines, and those reporting auras vs those without.

3.1.2. Nonpain secondary outcome measures

The benefits in favor of the PRF group did not extend to secondary outcome measures. Although reduction in severe headache frequency for occipital pain and overall headache/migraine favored the PRF group, the differences did not reach significance at any time point (Table 3). The use of rescue medications for ON and migraine with occipital nerve tenderness also did not differ at any follow-up. No differences were noted for headache-related disability, sleep quality, medication reduction or depression score at any follow-up, except that the PRF group experienced a lower Athens Insomnia score at 6 months than the steroid group (mean change from baseline −2.097 [5.696] vs 0.485 [4.285]; P = 0.033). There were no differences in any secondary outcome measure when either the ON or migraine with occipital nerve tenderness groups was analyzed separately.

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes according to treatment group.*

| Pulsed radiofrequency group

|

Steroid injection group

|

Treatment comparison

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | Overall mean (SD) | Mean change from baseline | No. of patients | Overall mean (SD) | Mean change from baseline | Adjusted difference (95% CI)† | P | |

| Severe headache frequency‡ | ||||||||

| Baseline | ||||||||

| Migraine | 25 | 3.640 (2.099) | N/A | 21 | 3.140 (1.878) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Occipital neuralgia | 42 | 3.180 (2.192) | N/A | 39 | 3.230 (2.507) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 wk | N/A | |||||||

| Migraine | 24 | 1.708 (1.958) | −1.932 (2.694) | 20 | 1.810 (2.421) | −1.400 (2.945) | −0.558 (−2.276 to 1.159) | 0.515 |

| Occipital neuralgia | 41 | 1.436 (2.237) | −1.695 (2.847) | 38 | 1.436 (2.087) | −1.737 (2.956) | 0.042 (−1.261 to 1.344) | 0.949 |

| 3 mo | ||||||||

| Migraine | 23 | 2.087 (2.109) | −1.609 (2.743) | 19 | 2.263 (2.232) | −0.722 (2.218) | −1.609 (2.743) | 0.272 |

| Occipital neuralgia | 39 | 1.846 (2.335) | −1.346 (2.573) | 37 | 1.919 (2.046) | −1.194 (2.806) | −1.346 (2.573) | 0.808 |

| 6 mo | ||||||||

| Migraine | 23 | 2.044 (2.099) | −1.652 (2.569) | 19 | 2.368 (2.409) | −0.611 (2.404) | −1.041 (−2.632 to 0.549) | 0.193 |

| Occipital neuralgia | 39§ | 2.128 (2.308) | −1.064 (2.631) | 37 | 2.162 (2.154) | −0.944 (2.563) | −0.120 (−1.317 to 1.077) | 0.843 |

| Headache impact test§ | ||||||||

| Baseline | 42 | 65.024 (7.546) | N/A | 39 | 65.359 (6.397) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 wk | 40 | 60.087 (7.972) | −4.675 (8.257) | 38 | 59.553 (9.093) | −5.763 (1.443) | 1.088 (−2.780 to 4.956) | 0.577 |

| 3 mo | 39 | 59.718 (9.761) | −5.026 (10.668) | 36 | 60.556 (10.814) | −4.889 (10.136) | −0.1365 (−4.935 to 4.661) | 0.955 |

| 6 mo | 39 | 59.641 (10.251) | −5.126 (11.000) | 36 | 61.389 (8.800) | −4.056 (7.738) | −1.047 (−5.458 to 3.364) | 0.638 |

| Athens insomnia scale|| | ||||||||

| Baseline | 42 | 11.881 (5.518) | N/A | 39 | 9.461 (4.973) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 wk | 40 | 10.025 (5.972) | −1.4875 (5.035) | 38 | 8.132 (5.297) | −1.026 (3.680) | −0.461 (−2.459 to 1.536) | 0.647 |

| 3 mo | 39 | 9.539 (6.043) | −1.807 (5.086) | 36 | 9.069 (5.955) | 0.097 (4.456) | −1.905 (−4.113 to 0.303) | 0.090 |

| 6 mo | 39 | 9.256 (6.210) | −2.097 (5.696) | 36 | 9.431 (5.765) | 0.485 (4.285) | −2.548 (−4.883 to −0.213) | 0.033 |

| Beck depression inventory§¶ | ||||||||

| Baseline | 42 | 12.810 (11.254) | N/A | 39 | 11.795 (9.229) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 –wk | 40 | 12.775 (11.079) | −0.150 (7.361) | 38 | 10.842 (9.945) | −1.079 (7.881) | 0.929 (−2.509 to 4.366) | 0.592 |

| 3 mo | 39 | 11.333 (10.207) | −1.308 (8.424) | 36 | 11.972 (10.287) | −0.333 (8.998) | −0.974 (−4.984 to 3.304) | 0.630 |

| 6 mo | 39 | 12.590 (10.684) | −0.051 (8.924) | 36 | 12.250 (10.103) | −0.056 (9.112) | 0.004 (−4.178 to 4.156) | 0.998 |

Plus–minus values are means ± SD. CI denotes confidence interval. 3-month and 6-month outcomes for those who exited the study because of treatment failure were imputed by ‘last observed outcome carried forward.’ Numerical rating scores for pain are based on 0 to 10 numerical rating scales, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating severe pain. Differences in sample size reflect dropouts and missing observations.

Differences for pain scores were adjusted for baseline outcome values. Negative coefficients favor the pulsed radiofrequency group. Positive coefficients favor the steroid group.

Number of days in the past week with a headache score ≥7/10.

A 6-question scale measuring the impact of headaches on quality of life. Scores range from 36 to 78, with higher scores indicating greater negative impact. A score of <50 indicates minimal impact, while a score ≥60 indicates headaches are severely impacting one’s life.

An 8-question scale used to assess insomnia symptoms in those with sleep disorders. A score ≥6 indicates the presence of insomnia.

A revised 21-question scale measuring depression, in which 14 to 19 indicates mild depression and ≥29 indicates severe depression.

3.1.3. Categorical outcome and global perceived effect

The PRF group experienced higher success rates at all time periods than the steroid, although the proportion of successful procedures declined in both groups after 6 weeks (Table 4). At 6weeks, the success rates in the PRF and steroid groups were 61% and 36%, respectively (OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.127, 6.908; P = 0.022). At 3 and 6 months, the percentages in the PRF group that had a positive outcome were 34% and 26%, respectively, which favorably compared with the 14% and 8% in the steroid group that experienced a positive outcome at the same follow-up periods (3-month OR 3.20; 95% CI 1.009, 10.146; P = 0.038 and 6-month OR 3.91; 95% CI 0.981, 15.567; P = 0.053). The higher success rate in the PRF group was largely because of the greater reduction in pain scores, as the higher global perceived effect scores in the PRF did not reach significance at any time frame, coming closest at 6 months (mean in the PRF group 3.481, SD 1.353 vs 3.095, SD 1.241; P = 0.199).

Table 4.

Global perceived effect and positive categorical outcome over study course.

| Pulsed radiofrequency group

|

Steroid injection group

|

Comparison of means

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | Overall mean (SD) | No. of patients | Overall mean (SD) | P | |

| Global perceived effect* | |||||

| 6 wk | 41 | 3.665 (1.344) | 39 | 3.487 (1.222) | 0.539† |

| 3 mo | 39 | 3.455 (1.372) | 37 | 3.230 (1.234) | 0.455† |

| 6 mo | 39 | 3.481 (1.353) | 37 | 3.095 (1.241) | 0.199† |

|

| |||||

| No. of patients | Number/Percentage | No. of patients | Number/Percentage | P | |

|

| |||||

| Positive categorical outcome‡ | |||||

| 6 wk | 41 | 25/61 | 39 | 14/36 | 0.022§ |

| 3 mo | 39 | 13/34 | 37 | 5/14 | 0.038§ |

| 6 mo | 39 | 10/26 | 37 | 3/8 | 0.028§ |

Five-point Likert scale in which 1 = very unsatisfied with treatment results and 5 = very satisfied.

t test.

Defined as ≥2-point decrease in average occipital pain coupled with a score ≥4/5 for global perceived effect.

Fisher’s Exact Test.

3.1.4. Factors associated with treatment outcome

In univariate analysis, obesity (OR 2.59; 95% CI 0.862, 7.797; P= 0.090) and whether the headaches began during a deployment (OR 0.161; 95% CI 0.042, 0.616; P = 0.008) demonstrated a trend toward being associated with outcome and were included in multivariate analysis along with gender, migraine status, and treatment group.

In multivariate analysis, separate models were developed and analyzed. Parameter estimates were bootstrapped, and the final model selection was based on the lowest Akaike Information Criteria. The final model included only deployment status, which was negatively correlated with outcome (OR 0.167; 95% CI 0.040, 0.696; P = 0.014; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.141).

3.1.5. Effectiveness of blinding

The effectiveness of blinding was investigated before discharge by inquiring which group the participant believed they were assigned to (ie, PRF, steroids, or “doesn’t know”). Participants guessed the correct treatment group 28 out of 81 times (35%). Omitting the “doesn’t know” category resulted in correct classification in 28 out of 56 guesses (50%; P = 0.69).

3.1.6. Adverse events

Nine people experienced complications, none of which were serious. In the steroid group, one participant experienced dizziness postprocedure for less than 2 days, 2 people had increased swelling at the injection site (<1 week), 2 people experienced temporary worsening of their headache including one person who also experienced vomiting (up to 2 weeks), and another person experienced new-onset eye pain and blurred vision which were not attributable to treatment. In the 3 complications that occurred in the PRF group, there was one report of worsening headaches (<10 days), one of swelling (<4 days), and one rash that started 2 days after treatment and persisted for 1 week.

4. Discussion

The results of this study support the use of PRF for ON and migraine with occipital nerve tenderness but come with some caveats. Although PRF provided significantly better pain relief than steroid injections for the duration of the study, there was a drop off in benefits between 6 weeks and 3 months. In addition, there were no significant differences in secondary outcome measures such as headache impact or sleep quality, which may have been a function of power. Importantly, the benefits afforded by PRF were experienced by participants irrespective of their migraine status.

4.1. Comparison to other studies and explanation of findings

Our study supports multiple preclinical studies demonstrating antinociceptive effects for PRF in a variety of neuropathic pain models,3,44,53,54 as well as placebo-controlled clinical trials in neuropathic pain conditions such as postherpetic neuralgia and cervical radiculopathy.34,41,57 However, in these clinical trials, patients received PRF of the dorsal root ganglia instead of the peripheral nerve(s), which has been shown in preclinical26,46 and clinical studies16 to provide longer lasting histological effects and superior analgesia, respectively. Similar to the largest study evaluating PRF for ON, our participants had failed less invasive treatments, including in most cases steroid injections, which may have accentuated any differences.31 In addition to PRF and steroids, all participants also received local anesthetic to increase volume and facilitate blinding. In conventional RF studies, the preadministration of local anesthetic has been shown to increase lesion size,10,47 but whether it increases the size of the electrical field remains unknown. Our inclusion criteria were relatively broad, reflecting participants one might see in a headache clinic or primary care setting, and are consistent with principles of comparative-effectiveness research.9

There are several possible explanations for our findings including greater efficacy for PRF than for steroids, or similar efficacy but more sustained benefit, as previous studies evaluating steroid injections for other conditions have generally shown benefit for several weeks, after which the effects quickly dissipate.18,21,33,42,52 Another explanation is that both treatments would have comparable benefit in a treatment-naive population, but these participants were more likely to experience better relief with PRF, because most had already failed steroid injections. The observation that the relief of pain did not translate to improved secondary outcome measures implies that the affective-motivational aspect of pain may be greater than the sensory-discriminative component in ON, and highlights the complexity of treating neuropathic pain in individuals with psychosocial overlay.

In the subgroup analysis, the participants with migraine and occipital nerve tenderness fared better than those with ON without migraine. This may have been due to the smaller number of those with ON without migraines, which were insufficient to enable us to detect a difference, if one exists. In previous studies evaluating interventions targeting of the occipital nerves, no distinction was made between those suffering from ON alone, and those with other primary headache disorders.31,39,49,57

4.2. Generalizability

This study was performed at civilian, military, and VA hospitals. A heterogeneous population and broad inclusion criteria, which are often discouraged in placebo-controlled trials, were present in our study. Although these factors may reduce the likelihood of detecting a statistical difference between treatments, they represent a key tenet in comparative-effectiveness research and enhance external validity.30 For example, many studies targeting the occipital nerves with peripheral nerve stimulation or PRF in migraine and other forms of primary headache have used similar selection criteria (eg, response to blocks, tenderness, etc).31,39,49,57 Our results are readily generalizable to tertiary care and primary care settings where neurologists, pain physicians, and primary care providers who perform simple injections are often faced with the dilemma of either repeating a steroid injection in someone who obtained only temporary relief or considering a more invasive treatment that requires additional equipment. Ways in which the treatments offered in our study may differ from those offered in a nonresearch setting are that we used electrical stimulation to localize the nerves for the group that received steroid injections (which was necessary to maintain blinding and might enhance the benefit observed in the control group)32 and that we performed 3 treatment cycles instead of one. Preclinical studies are mixed regarding whether multiple cycles of PRF improve treatment results,44,53 whereas the only clinical study that examined this parameter showed a small added benefit when more than one cycle was administered.31

4.3. Limitations

There are several limitations to our study that warrant consideration. The absence of a placebo group generally makes efficacy difficult to assess, but this is not the case when statistical significance can be shown in a comparative-effectiveness study, and the comparison of 2 treatment groups more closely reflects the decisions that providers face when confronted with a patient who has previously failed pharmacotherapy or steroid injections. We permitted unblinding at 6 weeks in participants who failed to derive benefit from their assigned treatment, which precludes conclusions regarding long-term effectiveness but is consistent with other randomized, interventional pain studies.1,14,17,18,24 Allowing the participation of individuals who already failed to obtain long-term pain relief from steroids may have skewed our results in favor of PRF, although in clinical practice steroids are generally used for diagnostic procedures, and only those who fail steroid injections should be considered for PRF. Our study began enrolling patients 1 year before the preliminary edition of ICHD-3 was published,28 and therefore some of our patients diagnosed with ON based on second edition criteria,27 which do not mandate the presence of dysesthesias and/or allodynia, may not have met ON diagnostic criteria in ICHD-3 beta. However, interventions targeting the occipital nerve(s) have yielded benefit in many studies evaluating patients who did not meet formal criteria for ON.31,39,49,57 In addition, some of our participants were service members who sustained injuries during military operations, and hence may have been subject to different mechanisms of injury and greater psychosocial stressors than a purely civilian cohort, as is evidenced by the poorer outcomes in those who reported that their headaches started during a deployment.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest that patients with migraine with occipital nerve tenderness, and possibly ON by itself, who fail more conservative treatments should be considered for PRF. Future studies should seek to identify a phenotype of patients likely to respond to treatment, elucidate the mechanisms of action by which PRF may exert its analgesic effects, and consider the use of a true placebo group in study design.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Funded by a Congressional Grant from the Center for Rehabilitation Sciences Research, Bethesda, MD; Role of funding source: The role of the funding source was to pay for non-government personnel and to reimburse institutions for the costs of the procedures.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Benny Morlando, Amy McCoart, Michael Bartoszek, Scott Griffith, Ivan Lesnik, Mirinda Anderson-White, Fereshteh Soumekh, and Carole Anne Drastal for their help in support of this project.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Conflict of interest statement

Declaration of Interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest. S. P. Cohen has served on the Advisory Boards of Semnur Pharmaceuticals, Halyard, Regenesis, Zynerba, SPR and St. Jude Medical in the past 2 years. The corresponding author had full access to the data and assumes responsibility for submission of this manuscript (guarantor). Protocol and statistical code available upon request from corresponding author.

CliicalTrials.Gov Registration: NCT01670825.

Contributions: Study design: S. P. Cohen, B. L. Peterlin, P. F. Pasquina; Treatment of patients: S. P. Cohen, E. T. Neely, A. Gupta, J. Mali, D. C. Fu, M. B. Jacobs, A. J. Verdun, M. P. Stojanovic, S. Hanling, O. Constantinescu, R. L. White, Z. Zhao, B. C. McLean; Data collection: S. P. Cohen, E. T. Neely, C. Kurihara, A. Gupta, A. R. Plunkett, M. P. Stojanovic, B. C. McLean; Administrative assistance: S. P. Cohen, C. Kurihara, A. Gupta, A. R. Plunkett, S. Hanling, M. P. Stojanovic, R. L. White, P. F. Pasquina, Z. Zhao, B. C. McLean; Manuscript preparation: S. P. Cohen, L. Fulton, B. L. Peterlin; Statistical analysis: L. Fulton, S. P. Cohen; Review of manuscript: All authors.

References

- 1.Ackerman WE, III, Ahmad M. The efficacy of lumbar epidural steroid injections in patients with lumbar disc herniations. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1217–22. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000260307.16555.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afridi SK, Shields KG, Bhola R, Goadsby PJ. Greater occipital nerve injection in primary headache syndromes—prolonged effects from a single injection. PAIN. 2006;122:126–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aksu R, Ugur F, Bicer C, Menkü A, Güler G, Madenoğlu H, Canpolat DG, Boyaci A. The efficiency of pulsed radiofrequency application on L5 and L6 dorsal roots in rabbits developing neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:11–5. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181c76c21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrosini A, Vandenheede M, Rossi P, Aloj F, Sauli E, Pierelli F, Schoenen J. Suboccipital injection with a mixture of rapid- and long-acting steroids in cluster headache: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. PAIN. 2005;118:92–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anthony M. Headache and the greater occipital nerve. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992;94:297–301. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(92)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashkenazi A, Young WB. The effects of greater occipital nerve block and trigger point injection on brush allodynia and pain in migraine. Headache. 2003;45:350–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bovim G, Sand T. Cervicogenic headache, migraine without aura and tension-type headache. Diagnostic blockade of greater occipital and supra-orbital nerves. PAIN. 1992;51:43–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brouwers MC, Thabane L, Moher D, Straus SE. Comparative effectiveness research paradigm: implications for systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4202–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruners P, Müller H, Günther RW, Schmitz-Rode T, Mahnken AH. Fluid-modulated bipolar radiofrequency ablation: an ex-vivo evaluation study. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:258–66. doi: 10.1080/02841850701843085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caputi CA, Firetto V. Therapeutic blockade of greater occipital and supraorbital nerves in migraine patients. Headache. 1997;37:174–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3703174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi HJ, Oh IH, Choi SK, Lim YJ. Clinical outcomes of pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation for the treatment of occipital neuralgia. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51:281–5. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.51.5.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua NH, Vissers KC, Sluijter ME. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment in interventional pain management: mechanisms and potential indications—a review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:763–71. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0881-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SP, Hayek S, Semenov Y, Pasquina PF, White RL, Veizi E, Huang JH, Kurihara C, Zhao Z, Guthmiller K, Griffith SR, Verdun A, Giampetro DM, Vorobeychik Y. Epidural steroid injections, conservative treatment or combination treatment for cervical radiculopathy: a multi-center, randomized, comparative-effectiveness study. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1045–55. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen SP, Plunkett AR, Wilkinson I, Nguyen C, Kurihara C, Flagg A, II, Morlando B, White RL, Anderson-Barnes VC, Galvagno SM., Jr Headaches during war: analysis of presentation, treatment, and factors associated with outcome. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:94–108. doi: 10.1177/0333102411422382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SP, Sireci A, Wu CL, Larkin TM, Williams KA, Hurley RW. Pulsed radiofrequency of the dorsal root ganglia is superior to pharmacotherapy or pulsed radiofrequency of the intercostal nerves in the treatment of chronic postsurgical thoracic pain. Pain Physician. 2006;9:179–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SP, Strassels SA, Foster L, Marvel J, Williams K, Crooks M, Gross A, Kurihara C, Nguyen C, Williams N. Comparison of fluoroscopically guided and blind corticosteroid injections for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SP, White RL, Kurihara C, Larkin TM, Chang A, Griffith SR, Gilligan C, Larkin R, Morlando B, Pasquina PF, Yaksh TL, Nguyen C. Epidural steroids, etanercept, or saline in subacute sciatica: a multicenter randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:551–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dougherty C. Occipital neuralgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:411. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdine S, Yucel A, Cimen A, Aydin S, Sav A, Bilir A. Effects of pulsed versus conventional radiofrequency current on rabbit dorsal root ganglion morphology. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedly JL, Comstock BA, Turner JA, Heagerty PJ, Deyo RA, Sullivan SD, Bauer Z, Bresnahan BW, Avins AL, Nedeljkovic SS, Nerenz DR, Standaert C, Kessler L, Akuthota V, Annaswamy T, Chen A, Diehn F, Firtch W, Gerges FJ, Gilligan C, Goldberg H, Kennedy DJ, Mandel S, Tyburski M, Sanders W, Sibell D, Smuck M, Wasan A, Won L, Jarvik JG. A randomized trial of epidural glucocorticoid injections for spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabrhelík T, Michálek P, Adamus M. Pulsed radiofrequency therapy versus greater occipital nerve block in the management of refractory cervicogenic headache—a pilot study. Prague Med Rep. 2011;112:279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gawel MJ, Rothbart PJ. Occipital nerve block in the management of headache and cervical pain. Cephalalgia. 1992;12:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1992.1201009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghahreman A, Ferch R, Bogduk N. The efficacy of transforaminal injection of steroids for the treatment of lumbar radicular pain. Pain Med. 2010;11:1149–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Takeshima N, Noguchi T. Mechanisms of analgesic action of pulsed radiofrequency on adjuvant-induced pain in the rat: roles of descending adrenergic and serotonergic systems. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:249–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamann W, Abou-Sherif S, Thompson S, Hall S. Pulsed radiofrequency applied to dorsal root ganglia causes a selective increase in ATF3 in small neurons. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hecht JS. Occipital nerve blocks in postconcussive headaches: a retrospective review and report of ten patients. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2004;19:58–71. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horn SD, Gassaway J. Practice based evidence: incorporating clinical heterogeneity and patient-reported outcomes for comparative effectiveness research. Med Care. 2010;48(6 suppl):S17–22. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d57473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang JH, Galvagno S, Hameed H, Wilkinson I, Erdek MA, Patel A, Buckenmaier C, III, Rosenberg J, Cohen SP. Occipital nerve pulsed radiofrequency treatment: a multi-center study evaluating predictors of outcome. Pain Med. 2012;13:489–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaptchuk TJ, Stason WB, Davis RB, Legedza AR, Schnyer RN, Kerr CE, Stone DA, Nam BH, Kirsch I, Goldman RH. Sham device v inert pill: randomized controlled trial of two placebo treatments. BMJ. 2006;332:391–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38726.603310.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karppinen J, Malmivaara A, Kurunlahti M, Kyllönen E, Pienimäki T, Nieminen P, Ohinmaa A, Tervonen O, Vanharanta H. Periradicular infiltration for sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1059–67. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ke M, Yinghui F, Yi J, Xeuhua H, Xiaoming L, Zhijun C, Chao H, Yingwei W. Efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of thoracic postherpetic neuralgia from the angulus costae: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2013;16:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koopman JS, Dieleman JP, Huygen FJ, de Mos M, Martin CG, Sturkenboom MC. Incidence of facial pain in the general population. PAIN. 2009;147:122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, Ware JE, Jr, Garber WH, Batenhorst A, Cady R, Dahlöf CG, Dowson A, Tepper S. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:963–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1026119331193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambru G, Abu Bakar N, Stahlhut L, McCulloch S, Miller S, Shanahan P, Matharu MS. Greater occipital nerve blocks in chronic cluster headache: a prospective open-label study. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:338–43. doi: 10.1111/ene.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laboureyras E, Rivat C, Cahana A, Richebé P. Pulsed radiofrequency enhances morphine analgesia in neuropathic rats. Neuroreport. 2012;23:535–59. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283541179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magis D, Allena M, Bolla M, De Pasqua V, Remacle JM, Schoenen J. Occipital nerve stimulation for drug-resistant chronic cluster headache: a prospective pilot study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:314–21. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnusson T, Ragnarsson T, Bjornsson A. Occipital nerve release in patients with whiplash trauma and occipital neuralgia. Headache. 1996;36:32–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1996.3601032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makharita MY, Amr YM. Pulsed radiofrequency for chronic inguinal neuralgia. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E147–E55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marks RC, Houston T, Thulbourne T. Facet joint injection and facet nerve block: a randomized comparison in 86 patients with chronic low back pain. PAIN. 1992;49:325–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naja ZM, El-Rajab M, Al-Tannir MA, Ziade FM, Tawfik OM. Occipital nerve blockade for cervicogenic headache: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Pain Pract. 2006;6:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozsoylar O, Akcali D, Cizmeci P, Babacan A, Cahana A, Bolay H. Percutaneous pulsed radiofrequency reduces mechanical allodynia in a neuropathic pain model. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1406–11. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818060e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peres MF, Stiles MA, Siow HC, Rozen TD, Young WB, Silberstein SD. Greater occipital nerve blockade for cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:520–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Podhajsky RJ, Sekiguchi Y, Kikuchi S, Myers RR. The histologic effects of pulsed and continuous radiofrequency lesions at 42 degrees C to rat dorsal root ganglion and sciatic nerve. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1008–13. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000161005.31398.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Provenzano DA, Lassilla HC, Somers D. The effect of fluid injection on lesion size during radiofrequency treatment. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:338–42. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181e82d44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saadah HA, Taylor FB. Sustained headache syndrome associated with tender occipital nerve zones. Headache. 1987;27:201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2704201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saper JR, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, McCarville S, Sun M, Goadsby PJ ONSTIM Investigators. Occipital nerve stimulation for the treatment of intractable chronic migraine headache: ONSTIM feasibility study. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:271–85. doi: 10.1177/0333102410381142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:555–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stall RS. Noninvasive pulsed radio frequency energy in the treatment of occipital neuralgia with chronic, debilitating headache: a report of four cases. Pain Med. 2013;14:628–38. doi: 10.1111/pme.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tafazal S, Ng L, Chaudhary N, Sell P. Corticosteroids in peri-radicular infiltration for radicular pain: a randomised double blind controlled trial. One year results and subgroup analysis. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1220–5. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka N, Yamaga M, Tateyama S, Uno T, Tsuneyoshi I, Takasaki M. The effect of pulsed radiofrequency current on mechanical allodynia induced with resiniferatoxin in rats. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:784–90. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e9f62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vallejo R, Tilley DM, Williams J, Labak S, Aliaga L, Benyamin RM. Pulsed radiofrequency modulates pain regulatory gene expression along the nociceptive pathway. Pain Physician. 2013;16:E601–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanderhoek MD, Hoang HT, Goff B. Ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve blocks and pulsed radiofrequency ablation for diagnosis and treatment of occipital neuralgia. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;3:256–9. doi: 10.5812/aapm.10985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vanelderen P, Rouwette T, De Vooght P, Puylaert M, Heylen R, Vissers K, Van Zundert J. Pulsed radiofrequency for the treatment of occipital neuralgia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:148–51. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181d24713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Zundert J, Patijn J, Kessels A, Lame I, Van Suijlekom H, Van Kleef M. Pulsed radiofrequency adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion in chronic cervical radicular pain: a double blind sham controlled randomized clinical trial. PAIN. 2007;127:173–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. PCL-C for DSM-IV. National Center for PTSD–Behavioral Sciences Division; Boston: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu B, Ni J, Zhang C, Fu P, Yue J, Yang L. Changes in spinal cord metenkephalin levels and mechanical threshold values of pain after pulsed radio frequency in a spared nerve injury rat model. Neurol Res. 2012;34:408–14. doi: 10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]