Abstract

Introduction

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is recommended for all patients with intermediate thickness melanomas. We sought to identify such patients at low risk of SLN positivity.

Methods

All patients with intermediate thickness melanomas (1.01–4 mm) undergoing SLN biopsy at a single institution from 1995–2011 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression determined factors associated with a low risk of SLN positivity. Classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was used to stratify groups based on risk of positivity.

Results

Of the 952 study patients, 157 (16.5%) had a positive SLN. In the multivariate analysis, thickness <1.5 mm (OR= 0.29), age ≥60 (OR=0.69), present tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) (OR=0.60), absent lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (OR=0.46), and absent satellitosis (OR=0.44) were significantly associated with a low risk of SLN positivity. CART analysis identified thickness of 1.5 mm as being the primary cut point for risk of SLN metastasis. Patients with a thickness of <1.5 mm represented 36% of the total cohort and had a SLN positivity rate of 6.6% (95% CI=3.8–9.4%). In patients with melanomas <1.5 mm in thickness, the presence of additional low risk factors identified 257 patients (75% of patients with <1.5 mm melanomas) in which the rate of SLN positivity was <5%.

Discussion

Despite a SLN positivity rate of 16.5% overall, substantial heterogeneity of risk exists among patients with intermediate thickness melanoma. Most patients with melanoma between 1.01–1.5 mm have a risk of SLN positivity similar to that in patients with thin melanomas.

Introduction

Regional nodal metastasis in melanoma represents the single strongest prognostic factor for patients with localized disease.1–4 Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is well established as the standard method to assess the nodal status of patients in the absence of clinically palpable lymph node metastases. Although this technique has dramatically reduced the morbidity associated with lymph node staging, the precise indications for the procedure continue to be the subject of debate.

The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that all patients with melanoma greater than 1 mm in thickness be offered SLN biopsy.5 The utility of the procedure in patients with thick melanoma (>4 mm) has been cause for some debate, as the risk of distant metastases in these patients is high, regardless of nodal status.6,7 More contentious have been the indications for SLN biopsy in patients with thin melanoma (≤1 mm in thickness).4,8–11 In thin melanoma the overall SLN positivity rate is approximately 5%.10–13 This rate is often considered the minimum threshold to justify the performance of SLN biopsy, given that it approximates both the complication rate and the false negative rate of the procedure.14 Currently, it is recommended that SLN biopsy be at least discussed with patients who have thin melanoma >0.75 mm and offered to those at increased risk based upon the presence of mitoses or ulceration.5

Little debate has arisen on the role for SLN biopsy in patients with intermediate thickness melanoma. The overall SLN positivity rate in this group is 15–20%, and the prognostic value of the procedure is firmly established.2 We hypothesized that considerable heterogeneity exists among patients with intermediate thickness melanoma with regard to risk of SLN positivity and that “low risk” tumor characteristics are associated with a rate of SLN positivity of <5%. In the appropriate clinical scenario patients with such characteristics might be spared the SLN biopsy procedure.

Methods

Utilizing our institutional database of patients undergoing SLNB from 1995–2011, all patients with intermediate thickness (>1 mm up to and including 4 mm) melanomas were identified. As previously described, maximal thickness was determined upon completion of wide local excision.8 Thus, patients with a positive deep margin on biopsy were appropriately upstaged after careful pathologic review and excluded if total thickness >4 mm was found after definitive resection. At our institution, SLNB is routinely performed for patients with melanomas >1 mm in thickness.

The analyzed patient variables included age and sex. Primary tumor characteristics included anatomic site, tumor thickness, Clark level, mitoses, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), regression, ulceration, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) evident in H&E sections, and microsatellitosis. Pathologic variables were defined as previously reported.15 For lesions in which an individual characteristic was not recorded on the pathology report, the missing data was recorded as unknown.

SLNB was performed using the standard technique as previously described.16 All SLN specimens were reviewed by specialized surgical pathologists or dermatopathologists at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Lymph node specimens were stained for S100 and HMB45 as previously described.16

Descriptive and univariate statistics using chi-square were performed with SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) or Stata 12.0/IC statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Factors associated with SLN positivity were determined using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. A forward stepwise multivariate analysis was utilized, including all factors with a p-value < 0.10 in the univariate analyses. A classification tree analysis was performed using a recursive portioning algorithm (Salford Systems, San Diego, CA) to risk-stratify patients for SLN positivity.17 Only patients with complete data were included in the classification tree analyses. For all analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

Study Demographics

Overall, 952 patients undergoing SLN biopsy for intermediate thickness melanoma were included in the study. Their mean age was 55 years and the majority were male (58%). Thirty-six percent of the cohort had a thickness of less than 1.5 mm. The distribution of the remaining clinicopathologic characteristics is shown in Table 1. At least one positive SLN was identified in 157 patients for a SLN positivity rate of 16.5%. Twenty-nine patients (3%) subsequently developed a nodal recurrence following a falsely negative SLN biopsy; these patients were not included as part of the SLN positive cohort in the study. The lowest absolute risk of a positive SLN biopsy was observed in patients with thickness <1.5 mm (7.3%) and patients with absent mitoses (7.6%). LVI (n=64, 7%) and microsatellitosis (n=56, 6%) were unusual findings but were the individual factors associated with the highest rate of SLN positivity, 35.9% and 35.7% respectively.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Patients with Intermediate Thickness Melanoma Undergoing SLN Biopsy (n=952)

| Factor | Overall N (%) | SLN Negative | SLN Positive | Positivity Rate | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 952 (100) | 795 | 157 | 16.5% | -- | |

|

| ||||||

| Age | <60 | 567 (60) | 466 | 101 | 17.8% | 0.182 |

| ≥60 | 385 (40) | 329 | 56 | 14.5% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | Female | 397 (42) | 331 | 66 | 16.6% | 0.925 |

| Male | 555 (58) | 464 | 91 | 16.4% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Clark Level | II/III | 153 (16) | 133 | 20 | 13.1% | 0.447 |

| IV/V | 773 (81) | 640 | 133 | 17.2% | ||

| Unknown | 26 (3) | 22 | 4 | 15.4% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Thickness | 1.01–1.49 | 344 (36) | 319 | 25 | 7.3% | <0.001 |

| 1.50–4.00 | 608 (64) | 476 | 132 | 21.7% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mitosis | Absent | 79 (8) | 73 | 6 | 7.6% | 0.071 |

| Present | 829 (87) | 687 | 142 | 17.1% | ||

| Unknown | 44 (5) | 35 | 9 | 20.5% | ||

|

| ||||||

| TIL | Absent | 195 (20) | 152 | 43 | 22.1% | 0.043 |

| Present | 694 (73) | 592 | 102 | 14.7% | ||

| Unknown | 63 (7) | 51 | 12 | 19.0% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Regression | Absent | 693 (73) | 582 | 111 | 16.0% | 0.637 |

| Present | 169 (18) | 137 | 32 | 18.9% | ||

| Unknown | 90 (9) | 76 | 14 | 15.6% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Ulceration | Absent | 695 (73) | 595 | 100 | 14.4% | 0.014 |

| Present | 187 (20) | 147 | 40 | 21.4% | ||

| Unknown | 70 (7) | 53 | 17 | 24.3% | ||

|

| ||||||

| LVI | Absent | 793 (83) | 679 | 114 | 14.4% | <0.001 |

| Present | 64 (7) | 41 | 23 | 35.9% | ||

| Unknown | 95 (10) | 75 | 20 | 21.1% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Satellites | Absent | 781 (82) | 667 | 114 | 14.6% | <0.001 |

| Present | 56 (6) | 36 | 20 | 35.7% | ||

| Unknown | 115 (12) | 92 | 23 | 20.0% | ||

Factors Associated with a Decreased Rate of SLN Positivity

Univariate analysis was used to identify clinicopathologic factors associated with low risk of SLN positivity. Thickness <1.5 mm (OR=0.28), absent mitoses (OR=0.40), present TIL (OR=0.61), absent ulceration (OR=0.62), absent (OR=0.30) or unknown (OR=0.48) LVI, and absent (OR=0.31) or unknown (OR=0.45) satellitosis were all associated with decreased odds of SLN positivity. Table 2.

Table 2.

The Association of Factors with SLN Positivity by Univariate and Multivariate Regression (n=952)

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| OR | p-value | OR | p-value | ||

| Age | <60 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ≥60 | 0.79 | 0.183 | 0.69 | 0.047 | |

|

| |||||

| Gender | Female | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Male | 0.98 | 0.925 | -- | -- | |

|

| |||||

| Clark Level | II/III | 0.72 | 0.210 | -- | -- |

| IV/V | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Unknown | 0.87 | 0.809 | -- | -- | |

|

| |||||

| Thickness | 1.01–1.49 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| 1.50–4.00 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

|

| |||||

| Mitosis | Present | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Absent | 0.40 | 0.034 | 0.47 | 0.093 | |

| Unknown | 1.24 | 0.570 | 1.26 | 0.656 | |

|

| |||||

| TIL | Present | 0.61 | 0.015 | 0.60 | 0.018 |

| Absent | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Unknown | 0.83 | 0.613 | 0.51 | 0.188 | |

|

| |||||

| Regression | Present | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Absent | 0.82 | 0.361 | -- | -- | |

| Unknown | 0.79 | 0.499 | -- | -- | |

|

| |||||

| Ulceration | Present | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Absent | 0.62 | 0.021 | -- | -- | |

| Unknown | 1.18 | 0.619 | -- | -- | |

|

| |||||

| LVI | Present | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Absent | 0.30 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.010 | |

| Unknown | 0.48 | 0.040 | 0.94 | 0.916 | |

|

| |||||

| Satellites | Present | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Absent | 0.31 | <0.001 | 0.44 | 0.010 | |

| Unknown | 0.45 | 0.028 | 0.33 | 0.056 | |

A forward stepwise multivariate analysis was then performed. Thickness <1.5 mm demonstrated the strongest association with a decreased risk of SLN positivity (OR= 0.29). Additional factors associated with a decreased risk included age ≥60 (OR=0.69), present TIL (OR=0.60), absent LVI (OR=0.46), and absent satellitosis (OR=0.44). Table 2. To determine if the unknown data influenced the results, the univariate and multivariate analysis was additionally performed including only patients with complete data (n=814). The results remained unchanged, except that older age did not demonstrate a significant association with decreased SLN positivity in the multivariate analysis (OR=0.72, p=0.116, data not shown).

Risk of SLN Positivity Stratified via Classification and Regression Tree Analysis

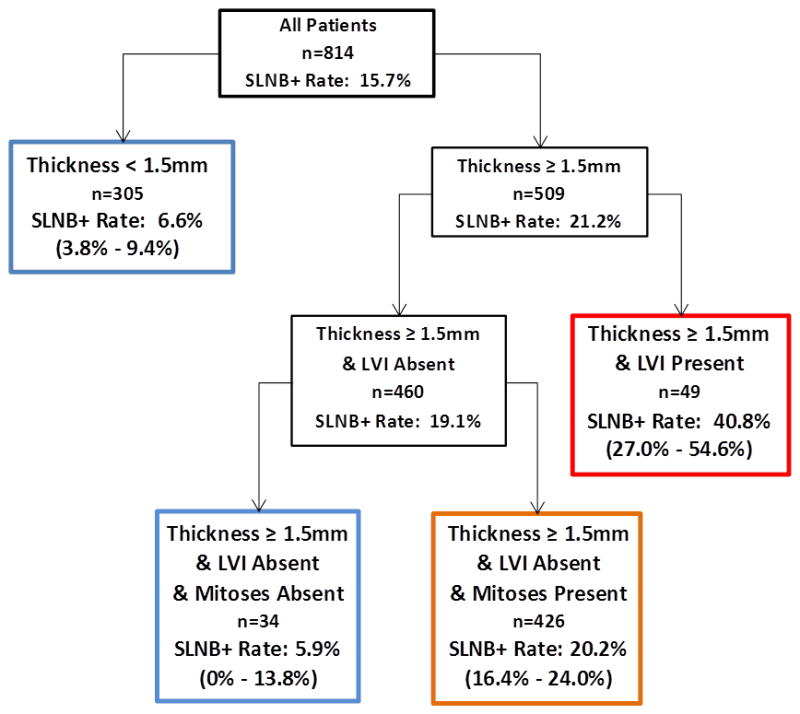

To better define the factors that could best differentiate patients at high or low risk for SLN positivity, a classification and regression tree (CART) was developed using patients in whom complete data were available (n=814). Figure 1. The CART algorithm identified thickness of 1.5 mm as the primary cut point for risk of SLN metastasis. Patients whose tumor thickness was <1.5 mm represented 37% of the total cohort. Regardless of other factors, this group had a risk of SLN positivity of 6.6% (95% CI=3.8–9.4%). Patients whose tumor thickness was ≥1.5 mm could be further risk stratified by the presence or absence of LVI. Those with LVI present were at particularly high risk of SLN positivity (40.8%, 95% CI=27–54.6%). Those without LVI could be further stratified into a low and high risk group. Patients with thickness ≥1.5 mm, absent LVI, and present mitoses represented the largest subgroup of patients in the regression tree and had a SLN positivity rate of 20.2% (95% CI = 16.4–24%). In the small number of patients with thickness ≥1.5 mm, absent LVI and absent mitoses (n=34, 4.2%), the SLN positivity rate was low (5.9%, 95% CI= 0–13.8%).

Figure 1.

Classification and Regression Tree Risk Stratification for SLN Positivity in Patients with Intermediate Thickness Melanoma. Blue boxes indicate groups at low risk of SLN positivity. Orange represents intermediate risk. Red indicates particularly increased risk.

Identification of Groups with a SLN Positivity Rate of Less Than 5%

In an exploratory analysis the two low risk groups identified by classification and regression tree analysis were further examined using descriptive statistics. Table 3. The first group included patients with melanomas <1.5 mm in thickness. Within this cohort, in the absence of mitoses, or in the presence of TIL with absent regression, the SLN positivity rate was 2.6% and 4.3%, respectively. Additionally, the subgroup of patients age 60 years and over who had one additional low risk factor demonstrated SLN positivity rates of 2.5–4.8%. In all, 257 patients with melanomas <1.5 mm were classified in these low risk groups, representing 75% of patients with <1.5 mm thick tumors and 27% of all patients with intermediate thickness melanoma. Of note, the SLN positivity rate in the 88 patients with melanomas <1.5 mm who did not fall into one of these low risk groups was 13.8%.

Table 3.

Low Risk Groups Among Patients with Intermediate Thickness Melanoma

| Factors | Number of Patients* | Positive SLN | SLN+ Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1.5 mm Thickness and: | |||

| No Mitoses | 38 | 1 | 2.6% |

| No Regression and Present TIL | 188 | 8 | 4.3% |

| <1.5 mm Thickness, Age ≥60 and: | |||

| No Regression | 79 | 2 | 2.5% |

| Present TIL | 86 | 4 | 4.7% |

| No Ulceration | 96 | 4 | 4.2% |

| No LVI | 106 | 5 | 4.7% |

| No Satellitosis | 104 | 5 | 4.8% |

|

| |||

| ≥1.5 mm Thickness, Absent LVI, Absent Mitoses and: | |||

| ≥60 | 21 | 0 | 0% |

| No Regression | 28 | 0 | 0% |

There is substantial overlap among groups of patients. Overall, 257 of the 344 patients with <1.5 mm melanoma and 32 of the 608 patients with 1.5–4 mm melanoma fall into at least one low risk group.

The second group included patients with tumors ≥1.5 mm in thickness. Only patients with absent LVI, absent mitoses, and either absent regression or age of 60 and over had a SLN positivity rate of <5% (n=32, 5% of patients ≥1.5 mm in thickness). Overall, 289 patients (30% of all patients with intermediate thickness melanoma) were classified in a group with a less than 5% risk of SLN positivity.

Discussion

We present our institutional experience with SLN biopsy in patients with intermediate thickness melanoma. Consistent with prior reports, we found an overall SLN positivity rate of 16.5% in this cohort. We furthermore identified factors associated with SLN positivity that are congruent with prior reports, including younger age, greater thickness, absent TIL, and present LVI or microsatellitosis.8,9,16,18–20 In this study, we use the absence of these risk factors to identify patients at particularly low risk for SLN positivity despite having a melanoma over 1 mm in thickness.

Although the overall risk of SLN positivity in patients with intermediate thickness melanoma is moderate, a substantial proportion (up to 30%) of all patients can be classified into groups with a risk of SLN positivity of <5%. Here we identify thickness, within the intermediate thickness group, as the dominant determinant of risk of SLN positivity. Thickness <1.5 mm was associated with the smallest odds ratio (OR=0.28) of any risk factor and was the primary cut point in the classification tree analysis.

Patients with a thickness between 1.01–1.5 mm represented a substantial proportion (36%) of the study population. Without any additional stratification, this group had a low risk of SLN positivity (6.6%). Further, 75% of patients with a thickness of <1.5 mm could be classified into a group with a risk of SLN positivity <5%. The majority (89%) of patients that could be identified as having a <5% risk of SLN positivity had a thickness of <1.5 mm.

The finding that present TIL and absent regression define a low risk group is intriguing. The interaction between present TIL and absent regression may be indicative of an effective immune response and has previously been associated with longer disease-specific survival in patients with thick melanomas.21 That TIL in the absence of regression is also associated with a low risk of nodal metastasis in intermediate melanoma supports the concept that the interaction of these factors is relevant to patient prognosis.

The factors identifying low risk groups are similar to those found by Mays et al., who identified a low risk cohort of patients with melanoma between 1–2 mm in thickness from the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial cohort.19 That study identified thickness less than 1.6 mm, absent LVI, and older age as the primary factors to stratify risk of SLN positivity. It is of note that the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial did not collect data on mitoses which have subsequently been incorporated into the staging system for thin melanomas.22 Because mitoses associate with the risk of SLN positivity in thin melanoma, we expected that it would have predictive value in lesions between 1–1.5 mm. However, in the multivariate model mitogenic status was not an independent predictor of risk of SLN positivity.

The use of a 5% risk of SLN positivity as the cut off to define “low risk” is somewhat arbitrary, although frequently employed. For the purposes of this study, the 5% risk approximates the risk of SLN positivity in patients with thin melanoma. In thin melanoma the NCCN guidelines only recommend SLN biopsy in select high risk groups, and in other moderate risk groups recommend that the decision be individualized in discussion with the patient.5 Taken together, our findings and those of Mays et al., suggest that the decision for SLN biopsy in patients with melanomas from 0.76–1.5 mm in thickness can be individualized based upon other risk factors and patient preferences. The current SLN biopsy guidelines have the convenience of overlapping with the staging system by employing a thickness cutoff of 1 mm and addressing only those other factors (mitoses/ulceration) that are also included among staging criteria. However, the risk factors for SLN metastasis, while similar, are not necessarily equivalent to risk factors for overall prognosis. Thus, while patients with a 1.01–1.5 mm lesion may be at increased risk of death from melanoma, the majority of these patients remain at quite low risk for SLN metastases, similar to patients with thin melanoma.

The heterogeneous risk of SLN metastasis among patients with intermediate thickness melanoma lends itself to the development of nomograms, and indeed these have previously been described.23 It appears, however, that thickness alone as a single variable offers significant risk stratification among patients with intermediate melanoma. In patients with melanomas <1.5 mm in thickness, nomograms may be of substantial utility given the numerous factors that contribute to the risk of SLN metastasis.

Our study has limitations. As a single institution-based, retrospective study of patients undergoing SLN biopsy, there may be selection bias in the group of patients in whom the procedure was performed. The practice at our institution has been to offer SLN biopsy to all patients with intermediate thickness melanomas, which may mitigate this bias. Indeed, our overall SLN positivity rate of 16.5% is similar to the 16.0% positivity rate observed in the population of the MSLT-1 trial.2 Furthermore, data missingness was modest. It reduced the sample size available for CART analysis by 15%, and unknowns were included in the multivariate analysis to determine if any were independently significant, and none were identified as such.

In conclusion, we find an overall SLN positivity rate of 16.5% in patients with intermediate thickness melanomas. However, there is substantial heterogeneity of risk within this group. As such, subsets of patients, particularly those with thickness between 1–1.5 mm have a risk of SLN positivity similar to that observed in patients with thin melanoma. For these patients, recommending the procedure based solely on a tumor thickness >1 mm may be too simplistic. A nuanced discussion regarding the risks and benefits of SLN biopsy may be warranted as part of shared decision making.

Synopsis.

Among patients with intermediate thickness melanomas, thickness <1.5 mm is the primary determinant of low risk for SLN positivity. Seventy-five percent of patients with lesional thickness between 1.01–1.5 mm can be classified into groups with a <5% rate of SLN positivity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants P50-CA093372, P30-CA016520, and P50-174523 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Karakousis GC, Gimotty PA, Czerniecki BJ, et al. Regional nodal metastatic disease is the strongest predictor of survival in patients with thin vertical growth phase melanomas: a case for SLN Staging biopsy in these patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007 May;14(5):1596–1603. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9319-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozzillo N, Caraco C, Chiofalo MG, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with cutaneous melanoma: outcome after 3-year follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004 May;30(4):440–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murali R, Haydu LE, Quinn MJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin primary cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 2012 Jan;255(1):128–133. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182306c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coit DG, Thompson JA, Andtbacka R, et al. Melanoma, version 4.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 May;12(5):621–629. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson GW, Murray DR, Hestley A, Staley CA, Lyles RH, Cohen C. Sentinel lymph node mapping for thick (>or=4-mm) melanoma: should we be doing it? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003 May;10(4):408–415. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gajdos C, Griffith KA, Wong SL, et al. Is there a benefit to sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with T4 melanoma? Cancer. 2009 Dec 15;115(24):5752–5760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartlett EK, Gimotty PA, Sinnamon AJ, et al. Clark level risk stratifies patients with mitogenic thin melanomas for sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Feb;21(2):643–649. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3313-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han D, Zager JS, Shyr Y, et al. Clinicopathologic predictors of sentinel lymph node metastasis in thin melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec 10;31(35):4387–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karakousis GC, Gimotty PA, Botbyl JD, et al. Predictors of regional nodal disease in patients with thin melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 Apr;13(4):533–541. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warycha MA, Zakrzewski J, Ni Q, et al. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node positivity in thin melanoma (<or=1 mm) Cancer. 2009 Feb 15;115(4):869–879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinnon JG, Yu XQ, McCarthy WH, Thompson JF. Prognosis for patients with thin cutaneous melanoma: long-term survival data from New South Wales Central Cancer Registry and the Sydney Melanoma Unit. Cancer. 2003 Sep 15;98(6):1223–1231. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright BE, Scheri RP, Ye X, et al. Importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Arch Surg. 2008 Sep;143(9):892–899. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.892. discussion 899–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Essner R, et al. Validation of the accuracy of intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: a multicenter trial. Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial Group. Ann Surg. 1999 Oct;230(4):453–463. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00001. discussion 463–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gimotty PA, Guerry D, Ming ME, et al. Thin primary cutaneous malignant melanoma: a prognostic tree for 10-year metastasis is more accurate than American Joint Committee on Cancer staging. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Sep 15;22(18):3668–3676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kesmodel SB, Karakousis GC, Botbyl JD, et al. Mitotic rate as a predictor of sentinel lymph node positivity in patients with thin melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005 Jun;12(6):449–458. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinberg DCP. CART: Tree-Structured Non-Parametric Data Analysis. San Diego: Salford Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor RC, Patel A, Panageas KS, Busam KJ, Brady MS. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict sentinel lymph node positivity in patients with cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Mar 1;25(7):869–875. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mays MP, Martin RC, Burton A, et al. Should all patients with melanoma between 1 and 2 mm Breslow thickness undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy? Cancer. 2010 Mar 15;116(6):1535–1544. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balch CM, Thompson JF, Gershenwald JE, et al. Age as a predictor of sentinel node metastasis among patients with localized melanoma: an inverse correlation of melanoma mortality and incidence of sentinel node metastasis among young and old patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Apr;21(4):1075–1081. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3464-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cintolo JA, Gimotty P, Blair A, et al. Local immune response predicts survival in patients with thick (t4) melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 Oct;20(11):3610–3617. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Dec 20;27(36):6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong SL, Kattan MW, McMasters KM, Coit DG. A nomogram that predicts the presence of sentinel node metastasis in melanoma with better discrimination than the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005 Apr;12(4):282–288. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]