Abstract

BACKGROUND

For every maternal death, over 100 women experience severe maternal morbidity, a life threatening diagnosis or undergo a life-saving procedure, during their delivery hospitalization. Similar to racial/ethnic disparities in maternal mortality, black women are more likely to suffer from severe maternal morbidity than white women. Site of care has received attention as a mechanism explaining disparities in other areas of medicine. Data indicate that blacks receive care in a concentrated set of hospitals and these hospitals appear to provide lower quality of care. Whether racial differences in site of delivery contribute to observed black-white disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates is unknown.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether hospitals with high proportions of black deliveries have higher severe maternal morbidity and if such differences contribute to overall black-white disparities in severe maternal morbidity.

STUDY DESIGN

We used a published algorithm to identify cases of severe maternal morbidity during deliveries in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2010 and 2011. We ranked hospitals by their proportion of black deliveries into high black-serving (top 5%), medium black-serving (5% to 25% range) and low black-serving hospitals. We analyzed the risks of severe maternal morbidity for black and white women by hospital black-serving status using logistic regressions adjusted for patient characteristics, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, and within-hospital clustering. We then derived adjusted rates from these models.

RESULTS

Seventy-four percent of black deliveries occurred at high and medium black-serving hospitals. Overall, severe maternal morbidity occurred more frequently among black than white women (25.8 vs. 11.8 per 1000 deliveries, p<.001); after adjusting for the distribution of patient characteristics and comorbidities, this differential declined, but remained elevated (18.8 vs. 13.3per 1000 deliveries respectively, p<.001). Women delivering in high and medium black-serving hospitals had elevated rates of severe maternal morbidity rates compared with those in low black-serving hospitals in unadjusted (29.4, 19.4, versus 12.2 per 1000 deliveries respectively, p<0 .001) and adjusted analyses (17.3, 16.5 vs. 13.5 per 1000 deliveries respectively, p<.001). Black women who delivered at high black-serving hospitals had the highest risk of poor outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Most black deliveries occur in a concentrated set of hospitals, and these hospitals have higher severe maternal morbidity rates. Targeting quality improvement efforts at these hospitals may improve care for all deliveries and disproportionately impact care for black women.

Keywords: severe maternal morbidity, quality of care, obstetrics, disparities

Deaths associated with pregnancy in the United States are the “tip of the iceberg”;1 for every maternal death, over a 100 women experience severe maternal morbidity, a life threatening diagnosis or undergo a life-saving procedure during delivery hospitalization.1,2 Severe maternal morbidity affects ~60,000 women annually in the US.2,3 Similar to racial/ethnic disparities in maternal mortality, black women are more likely to suffer from severe maternal morbidity than white women.1 Data suggest that a significant proportion of maternal mortality and morbidity may be preventable,4-6 making quality of health care delivered in hospitals an essential lever for improving outcomes and narrowing disparities.

Site of care has received increasing attention as a mechanism explaining disparities. Prior studies have documented that blacks receive care in a concentrated set of hospitals and these hospitals appear to provide lower quality of care.7,8 For example, investigators have found that hospitals with higher proportion of black patients have higher mortality for surgery, heart attacks, and very low birth weight neonates.9-11 In obstetrics, investigators documented that black-serving hospitals performed worse than other hospitals on 12 of 15 delivery-related indicators.12 Whether racial differences in site of delivery contribute to observed black-white disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates is unknown. The objectives of this study were to examine whether hospitals with high proportions of black deliveries have higher severe maternal morbidity rates and if such differences contribute to overall black-white disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used data from the 2010 and 2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, a federal–state–industry partnership sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Nationwide Inpatient Sample is a stratified sample representing 20% of U.S. community hospitals. Each record is weighted to account for the complex sampling and when weights are applied during analysis, nationwide estimates can be derived.(http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2011.jsp. Accessed 10/8/2014.) The Nationwide Inpatient Sample data does not include personal identifiers. The Mount Sinai Program for Protection of Human Subjects (Institutional Review Board) deemed this research exempt.

STUDY SAMPLE

Delivery hospitalizations were identified based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes and DRG delivery codes.13 We examined all deliveries that occurred in hospitals with at least 10 deliveries annually, because we wanted to analyze hospitals with an obstetric volume high enough to preclude hospitals with no routine obstetrical practice and therefore excluded 408 (77 unweighted) deliveries at 171 hospitals (35 unweighted). We limited our analyses to black and white deliveries and excluded 2,472,365 additional deliveries on this basis. Some hospitals do not routinely record data on race/ethnicity in their hospital discharge summaries and thus race was missing for 722 hospitals (152 unweighted) approximately 11.2% of the hospitals. This resulted in the exclusion of .005% white deliveries and .007% black deliveries. Severe maternal morbidity was not different for deliveries in the hospitals with and without data on race (1.51 vs. 1.34, p=0.37). Our analysis thus included 5,539 (1,146 unweighted, 1140 unique hospitals for combined 2010-2011 dataset) hospitals that provided delivery services and 4,609,291 (942,622 unweighted) deliveries. Only national estimates are presented in the results section.

SEVERE MATERNAL MORBIDITY

We used a published algorithm defined by investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to identify severe maternal morbidity (primary outcome), which is a potentially life-threatening diagnosis or receipt of a life-saving procedure (e.g. renal failure, shock, embolism, eclampsia, septicemia, mechanical ventilation, transfusion).2 The algorithm includes 25 categories that capture indicators of organ-system dysfunction. It hierarchically classifies all severe maternal morbidity hospitalizations associated with in-hospital mortality or transfer as hospitalizations with severe complications regardless of the length of stay. In-hospital mortality was identified using the variable “died during hospitalization” and transfer status using “disposition of patient” or “admission source” in NIS. Length of stay is also a part of this algorithm. Hospitalizations with severe morbidity and a short length of stay were not classified as cases of severe maternal morbidity as specified by the CDC algorithm. Short length of hospital stay was defined as length of stay less than the 90th percentile as calculated separately for vaginal, primary, and repeat cesarean deliveries. Length of stay restrictions were not applied to delivery hospitalizations with severe complications identified by procedure codes (e.g., hysterectomy, blood transfusion, ventilation) as recommended.2

BLACK-SERVING DELIVERY HOSPITALS

Similar to methods used by Jha et al,8,14 we ranked hospitals by their proportion of black deliveries among all deliveries and chose two cut off points. We defined the top 5% of hospitals as high black-serving hospitals, the next 20% (those in the >5% to <=25% range) as medium black-serving hospitals, and the remaining 75% of hospitals as low black-serving hospitals. 279 hospitals (5%) were designated as high black-serving, 1106 hospitals (20 percent) were designated as medium black-serving, and 4102 (75%) as low black serving.

CO-VARIABLES

Risk adjustment variables were chosen by their association with the outcome, biological plausibility, and prior research.15,16 Our aim was to adjust for factors likely to affect maternal morbidity and hospital of delivery. We included maternal sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, zip code income), clinical factors (e.g. multiple births, previous cesarean delivery) and comorbid conditions and antepartum complications (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, obesity, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, disorders of placentation).17 Hospital characteristics included teaching status, hospital ownership, delivery volume, rural or urban location, hospital region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), bedsize, and percent of Medicaid admissions as a proxy for the proportion of poor patients the hospitals serves.

ANALYSIS

We compared the characteristics of black versus white women with severe maternal morbidity using Rao-Scot chi square tests for categorical data. We used analysis of variance and chi square tests as appropriate to examine the characteristics of delivery hospitals according to the proportion of their black deliveries. For our primary outcome, risk-adjusted probability of severe maternal morbidity, we estimated four multivariable patient-level logistic regression models. Each model incorporated the survey weights; the variance estimates accounted for the NIS sampling structure.18

The first model included race and patient risk factors only; the second included these variables plus indicator variables for whether the hospital was a high-, medium-, or low-black serving hospital. The third included these variables plus the other hospital levels variables listed above. For the fourth model, we included patient risk factors, race, and black-serving status of the hospital, and variables representing the interaction between race and black-serving status of the hospital. Using this model, we estimated the risk-adjusted predicted probability of severe maternal morbidity for six categories of race and hospital: black and white patients, respectively, at high black-serving hospitals; black and white patients, respectively, at medium black-serving hospitals; and black and white patients, respectively, at low black-serving hospitals. We used recycled predictions to calculate predicted probabilities using the margins command; confidence intervals were estimated using the delta method.19

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we estimated the multivariable patient-level logistic regression model and added cesarean as a covariate. Second, we conducted the analyses after excluding hospitals with <30 deliveries. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS system software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and Stata/SE 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). All tests were two-tailed and a p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In 2010 and 2011 there were 3,584,639 (78%) deliveries to white women and 1,024,652 (22%) to black women. Black women were more likely to be younger, have Medicaid insurance, live in lower-income zip code neighborhoods, and have more comorbid conditions than white women (Table 1). Of the 4.6 million total deliveries, 68,841 were associated with severe maternal morbidity (15.0 cases per 1000).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Race

| Maternal Characteristics | White | Black | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| 3,584,639 | 77.8 | 1,024,652 | 22.2 | ||

| Maternal age | <.001 | ||||

| <20 | 239,101 | 6.7 | 146,589 | 14.3 | |

| 20-29 | 1,831,669 | 51.1 | 582,108 | 56.8 | |

| 30-34 | 967,307 | 27.0 | 181,903 | 17.8 | |

| 35-39 | 439,096 | 12.2 | 89,397 | 8.7 | |

| 40-44 | 100,657 | 2.8 | 22,985 | 2.2 | |

| 45+ | 6,809 | 0.2 | 1670 | 0.2 | |

| Medicaid | 1,275,279 | 35.6 | 708,208 | 69.1 | <.001 |

| Zipcode income (dollars) | <.001 | ||||

| <41 000 | 726,779 | 20.5 | 466,830 | 47.0 | |

| 41 000 to <51 000 | 870,385 | 24.6 | 213,907 | 21.6 | |

| 51 000 to <67 000 | 981,061 | 27.7 | 188,202 | 19.0 | |

| 67000+ | 965,345 | 27.2 | 123,605 | 12.5 | |

| Most prevalent co-morbidities and complications | |||||

| Prior cesarean delivery | 582,580 | 16.3 | 182,113 | 17.8 | <.001 |

| Blood disorders | 345,259 | 9.6 | 188,671 | 18.4 | <.001 |

| Pregnancy hypertension | 146,757 | 4.1 | 65,796 | 6.4 | <.001 |

| Chronic hypertension | 51,908 | 1.4 | 34,120 | 3.3 | <.001 |

| Asthma/other pulmonary | 129,404 | 3.6 | 58,253 | 5.7 | <.001 |

| Multiple gestations | 66,946 | 1.9 | 18,705 | 1.8 | 0.43 |

| Placental disorder | 54,806 | 1.5 | 19,508 | 1.9 | <.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 30,198 | 0.8 | 13,754 | 1.3 | <.001 |

| Diabetes other | 27,528 | 0.8 | 12,465 | 1.2 | <.001 |

| Diagnosis of obesity | 144,539 | 4.0 | 76,675 | 7.5 | <.001 |

| Cardiac disease | 15,635 | 0.4 | 3,805 | 0.4 | 0.007 |

| ≥ 1 co-morbidity /risk factor | 1,392,932 | 38.9 | 502,988 | 49.1 | <.001 |

Note: National estimates for deliveries in hospitals with at least 10 deliveries and 80% not-missing race

High black-serving hospitals provided delivery services for approximately 24.0% of all black deliveries and medium black-serving hospitals cared for an additional 49.7 percent of black pregnant women. Thus, high and medium black-serving hospitals provided delivery services for 73.7 percent of all black deliveries. In comparison, high black-serving hospitals provided delivery services for 1.8% of all white deliveries and medium black-serving hospitals provided delivery services for 16.0% of all white deliveries.

Both high and medium black-serving hospitals had different characteristics from low black-serving hospitals (Table 2). Black-serving hospitals were more likely to be: located in an urban area, located in the South, be a teaching hospital, have a higher delivery volume, have larger bed size, and have a higher proportion of Medicaid deliveries.

Table 2.

Hospital Characteristics for High, Medium and Low Proportion of Black Deliveries

| High (n=279) | Medium (n=1106) | Low (n=4102) | P value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Black deliveries (%), median (range) | 58.6 (46.7, 98.6) | 26.4 (20.8, 45.8) | 2.2 (0.0, 20.5) | ||||

| Bed Size | <0.001 | ||||||

| Small | 39 | 14.0 | 181 | 16.3 | 1186 | 28.9 | |

| Medium | 59 | 21.1 | 322 | 29.1 | 1267 | 30.9 | |

| Large | 176 | 63.1 | 589 | 53.3 | 1590 | 38.8 | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.8 | 14 | 1.3 | 59 | 1.4 | |

| Location | <.001 | ||||||

| Rural | 88 | 31.7 | 235 | 21.2 | 1606 | 39.2 | |

| Urban | 185 | 66.5 | 857 | 77.5 | 2437 | 59.4 | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.8 | 14 | 1.3 | 59 | 1.4 | |

| Hospital Region | <.001 | ||||||

| Northeast | 39 | 13.8 | 145 | 13.1 | 698 | 17.0 | |

| Midwest | 59 | 21.0 | 111 | 10.1 | 1170 | 28.5 | |

| South | 181 | 65.1 | 802 | 72.5 | 1054 | 25.7 | |

| West | *<=2 | * | 48 | 4.4 | 1180 | 28.8 | |

| Hospital Control | 0.110 | ||||||

| Government, nonfederal | 74 | 26.4 | 238 | 21.6 | 703 | 17.1 | |

| Private, not-profit | 156 | 56.2 | 638 | 57.7 | 2767 | 67.4 | |

| Private, invest-own | 44 | 15.7 | 216 | 19.5 | 573 | 14.0 | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.8 | 14 | 1.3 | 59 | 1.4 | |

| Teaching Status | <.001 | ||||||

| Not teaching | 142 | 50.9 | 717 | 64.8 | 3280 | 80.0 | |

| Teaching | 132 | 47.4 | 374 | 33.9 | 763 | 18.6 | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.8 | 14 | 1.3 | 59 | 1.4 | |

| Delivery Volume (quintiles) | 0.004 | ||||||

| Very low (12-1021) | 147 | 52.8 | 449 | 40.6 | 2637 | 64.3 | |

| Low (1022-1888) | 54 | 19.3 | 296 | 26.8 | 646 | 15.8 | |

| Median (1900-2829) | 34 | 12.3 | 185 | 16.7 | 386 | 9.4 | |

| High median (2833-4143) | 34 | 12.2 | 108 | 9.7 | 282 | 6.9 | |

| High (4155-13010) | 10 | 3.5 | 68 | 6.2 | 150 | 3.7 | |

| Percent Medicaid Deliveries (quintiles) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Very low (<15.8%) | 10 | 3.5 | 156 | 14.1 | 800 | 19.7 | |

| Low (15.9-23.4%) | 19 | 7.0 | 205 | 18.5 | 907 | 22.2 | |

| Median (23.4-30.6%) | 25 | 8.9 | 189 | 17.1 | 945 | 23.1 | |

| High median (30.6-39.0%) | 68 | 24.6 | 249 | 22.5 | 784 | 19.2 | |

| High (39.0-89.5%) | 156 | 56.1 | 307 | 27.7 | 646 | 15.8 | |

Note: National estimates for hospitals with at least 10 deliveries and 80% not-missing race

<=2 Number is masked based on the HCUP privacy protection rules

Table 3 presents crude and adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity by race and site of care. Unadjusted rates were higher among blacks than whites (25.8 vs. 11.8 per 1000 deliveries respectively, p<.0001). Excess comorbidities among black women explained a significant portion of this disparity. After adjustment for patient characteristics and comorbidities, the rates were 18.8 and 13.3 respectively (p<.0001). These rates are those that would be expected if patient characteristics and comorbidities in the population were similarly distributed among whites and blacks, which leads to an increase for whites and a decrease for blacks. Women delivering in high and medium black-serving hospitals had higher severe maternal morbidity rates than those in low black-serving hospitals (29.4, 19.4, versus 12.2 per 1000 deliveries respectively, p<0 .001). Adjustment for sociodemographic, clinical, and hospital factors attenuated these differences (17.3, 16.5 vs. 13.5 per 1000 deliveries respectively, p<.001).

Table 3.

Severe Maternal Morbidity Rates by Race and Site of Care, per 1000 Deliveries

| No. of Deliveries (National Estimates) | Unadjusted rate (95% CI) | Rate adjusted for patient characteristics (95% CI) | Rate adjusted for patient characteristics and site of care (95% CI) | Rate adjusted for patient and hospital characteristics (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||||

| White | 3,584,639 | 11.8 (11.2-12.5) | 13.3 (12.5-14.1) | 13.8 (12.9-14.7) | 13.8 (12.9-14.7) |

| Black | 1,024,652 | 25.8 (2.35-2.80) | 18.8 (17.1-20.5) | 17.3 (16.1-18.5) | 17.3 (16.2-18.4) |

| Site of care | |||||

| Low black-serving hospitals | 3,279,641 | 11.8 (11.0-12.6) | 13.4 (12.6-14.3) | 13.5 (12.6-14.5) | |

| Medium black-serving hospitals | 1,000,458 | 18.4 (16.8-20.1) | 16.5 (15.1-17.9) | 16.5 (15.0-18.0) | |

| High black-serving hospitals | 329,193 | 29.1 (21.6-36.5) | 18.1 (13.5-22.7) | 17.3 (12.9-21.7) |

Patient characteristics include age, insurance, zip code income, comorbidities and pregnancy complications.1

Hospital factors include teaching status, bed size, location, region, control, volume of deliveries, percent Medicaid deliveries.

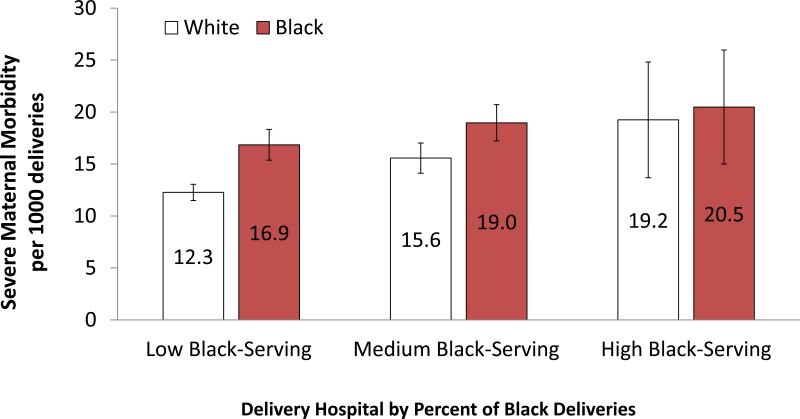

Figure 1 presents adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity for black and white women by black-serving hospital status. Of the six groups, white patients at low black-serving hospitals had the lowest rates of adjusted severe maternal morbidity (12.3 per 1000 deliveries) and black patients at high black-serving hospitals had the highest (20.5 per 1000 deliveries). White patients at high black-serving hospitals also had elevated adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity (19.2 per 1000 deliveries). As compared with white women who delivered at low black-serving hospitals, black and white women who delivered at high black-serving hospitals had 66.9% (p=.002) and 56.9% (p=.006) respectively higher adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity. Results were essentially unchanged for the analysis which included cesarean as a covariate in the multivariable model. Likewise the results were unchanged when we used a different obstetrical volume (<30 deliveries annually) to exclude hospitals from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Risk –adjusted Severe Maternal Morbidity Rates for Black and White Deliveries by Site of Care.

COMMENT

We found that severe maternal morbidity occurred more than twice as often in black deliveries than white deliveries. While some of these differences were due to higher rates of comorbidity among black than white women, our data demonstrate that some of these disparities may be caused by differences in the health care settings where white and black women receive obstetrical delivery care. We examined the concentration of delivery care for black women and found that a quarter of hospitals provided care for three quarters of all black deliveries in the Unites States. Hospitals that disproportionately cared for black deliveries had higher severe maternal morbidity rates after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics.

Understanding why racial disparities in maternal outcomes exist is the first step in eliminating them. The vast majority of research on racial/ethnic disparities in obstetrics has attributed differences in outcomes to social and biological/genetic factors,20 and has not accounted for the systems within which obstetric care is delivered and how differences in quality of care may contribute to disparities.8 We found that both black and white patients who delivered in black-serving hospitals had a higher risk of severe maternal morbidity after accounting for patient characteristics. Adjusting for differences in hospital characteristics had little effect on our primary findings and may suggest that quality of care at hospitals that disproportionately serve blacks is lower than quality at low black-serving hospitals.

Our results are similar to findings in other reports.9-11,21,22 In obstetrics, investigators found that black-serving hospitals performed worse than other hospitals on the majority of delivery-related indicators using data from seven states.12 Our study builds on this previous work by giving national estimates and examining severe maternal morbidity as the outcome of interest. Further, we used methods to categorize black-serving hospitals employed in healthcare quality assessment,8,14 and were thus able to examine both the concentration of care by race, and the extent to which racial differences in site of care contribute to racial differences in severe maternal morbidity. In other areas of medicine, multiple studies have demonstrated that blacks receive care in a concentrated set of hospitals and that these hospitals appear to provide lower quality of care. Disparities in outcomes including acute MI, surgical mortality, VLBW mortality, and readmission for CHF and acute MI have been found to be due in part to where minorities and whites receive care.9-11,21,22 Similarly, disparities in receipt of appropriate care such as thrombotic therapy, angioplasty, carotid imaging, and provision of timely antibiotics for pneumonia are lower in hospitals that serve a high proportion of blacks.7,8,23 Our findings add to this body of literature and suggest that targeting interventions to improve care at hospitals that serve a high proportion of blacks may reduce poor outcomes and racial/ethnic disparities.

After adjusting for patient- and hospital-level factors, black women had higher adjusted rate of severe maternal morbidity than white women. Our results confirm the high risk of adverse outcomes faced by black women giving birth in comparison with white women in the US and are similar to findings by others.16,24 Comorbidities and pregnancy complications have been demonstrated to be highly associated with severe maternal morbidity,17 and explained a significant portion of the elevated risk for severe maternal morbidity among blacks in this cohort.

Both black and white women who delivered at high black-serving hospitals had higher adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity. Chronic illnesses and pregnancy complications require close antepartum management and it is possible that the availability of high quality antenatal care is limited for patients who deliver at black-serving hospitals. Targeted preventive community based programs (both preconceptually and antenatally) in the catchment areas serving these hospitals may be an important step to reducing disparities.25,26

Our study had limitations. We used administrative data (ICD-9 procedure and diagnosis codes) that do not contain important clinical data on severity of illness, and may have constrained our ability to adequately risk-adjust. For example, we were unable to control for adequacy of prenatal care, parity, medication exposure, number of previous cesareans, and other clinical factors that may be associated with severe maternal morbidity. In addition our use of administrative data limited our ability to adequately adjust for obesity. We limited our study to care for black and white deliveries because administrative data sources are often less reliable for other race/ethnicity groups.27 Nevertheless, we constructed a robust model that adjusted for variation in comorbidities and obstetrical complications across these racial groups and hospitals.

Three quarters of black deliveries in the United States occur in a quarter of the hospitals, and our data suggests that these hospitals may provide lower quality of care. Our findings highlight the need for targeting quality improvement efforts that address both antenatal and delivery care factors for pregnant women who deliver at these hospitals. This strategy has the potential to improve care for all women who deliver in these hospitals and can have a disproportionate impact on the care of black pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

Support by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD007651) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R21HD068765). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, Baltimore, MD, June 25, 2013.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199(2):133, e131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;120(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, et al. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014 Jan;23(1):3–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1987-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Aug;88(2):161–167. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoyert DL, Danel I, Tully P. Maternal mortality, United States and Canada, 1982-1997. Birth. 2000 Mar;27(1):4–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nannini A, Weiss J, Goldstein R, Fogerty S. Pregnancy-associated mortality at the end of the twentieth century: Massachusetts, 1990-1999. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57(3):140–143. Summer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng EM, Keyhani S, Ofner S, et al. Lower use of carotid artery imaging at minority-serving hospitals. Neurology. 2012 Jul 10;79(2):138–144. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f04c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007 Jun;167(11):1177–1182. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucas FL, Stukel TA, Morris AM, Siewers AE, Birkmeyer JD. Race and surgical mortality in the United States. Ann Surg. 2006 Feb;243(2):281–286. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197560.92456.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner J, Chandra A, Staiger D, Lee J, McClellan M. Mortality after acute myocardial infarction in hospitals that disproportionately treat black patients. Circulation. 2005 Oct 25;112(17):2634–2641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008 Mar;121(3):e407–415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Kuklina E, Shilkrut A, Callaghan WM. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun 5; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J. 2008 Jul;12(4):469–477. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez L, Jha AK. Outcomes for whites and blacks at hospitals that disproportionately care for black Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2013 Feb;48(1):114–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srinivas SK, Fager C, Lorch SA. Evaluating risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rate as a measure of obstetric quality. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;115(5):1007–1013. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d9f4b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray KE, Wallace ER, Nelson KR, Reed SD, Schiff MA. Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012 Nov;26(6):506–514. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014 Oct 15;312(15):1531–1541. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HCUP [January 26, 2015];Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2011 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2011.jsp#sw.

- 19.Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata Journal. 2012;12(2):308–331. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. APR. 2010;202(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011 Feb 16;305(7):675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005 Apr;43(4):308–319. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in time to acute reperfusion therapy for patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2004 Oct 6;292(13):1563–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008-2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 May;210(5):435, e431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Culhane JF, Hobel CJ, Klerman LV, Thorp JM., Jr. Preconception care between pregnancies: the content of internatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2006 Sep;10(5 Suppl):S107–122. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlinger J, Kantak A, Lavin JP, Jr., et al. Evaluation and development of potentially better practices for perinatal and neonatal communication and collaboration. Pediatrics. 2006 Nov;118(Suppl 2):S147–152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0913L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia H, Zheng YE, Cowper DC, et al. Race/ethnicity: who is counting what? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006 Jul-Aug;43(4):475–484. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.05.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]