Abstract

It has long been known that the bedding type animals are housed on can affect breeding behavior and cage environment. Yet little is known about its effects on evoked behavior responses or non-reflexive behaviors. C57BL/6 mice were housed for two weeks on one of five bedding types: Aspen Sani Chips® (standard bedding for our institute), ALPHA-Dri®, Cellu-Dri™, Pure-o’Cel™ or TEK-Fresh. Mice housed on Aspen exhibited the lowest (most sensitive) mechanical thresholds while those on TEK-Fresh exhibited 3-fold higher thresholds. While bedding type had no effect on responses to punctate or dynamic light touch stimuli, TEK-Fresh housed animals exhibited greater responsiveness in a noxious needle assay, than those housed on the other bedding types. Heat sensitivity was also affected by bedding as animals housed on Aspen exhibited the shortest (most sensitive) latencies to withdrawal whereas those housed on TEK-Fresh had the longest (least sensitive) latencies to response. Slight differences between bedding types were also seen in a moderate cold temperature preference assay. A modified tactile conditioned place preference chamber assay revealed that animals preferred TEK-Fresh to Aspen bedding. Bedding type had no effect in a non-reflexive wheel running assay. In both acute (two day) and chronic (5 week) inflammation induced by injection of Complete Freund’s Adjuvant in the hindpaw, mechanical thresholds were reduced in all groups regardless of bedding type, but TEK-Fresh and Pure-o’Cel™ groups exhibited a greater dynamic range between controls and inflamed cohorts than Aspen housed mice.

Keywords: mechanical behavior, mechanotransduction, bedding, cold behavior, chronic inflammation, acute inflammation, tactile place preference, wheel running

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, we noticed that the median von Frey thresholds our laboratory obtains from non-injured wild type mice are typically lower than those of many other groups7,18–20,23,37,38,67. It has been shown that many factors can affect behavioral response properties, such as density of mice in the cage, time allowed for acclimation before tests, stress levels of the animals, stress levels of the experimenters, noise in the animal facility, odors from compounds worn by experimenters or animal care takers, or the gender of the operator25,56. In addition, pain behavior is influenced by the time of day when the animals are tested; mice show a greater pain sensitivity during the light period, than during the dark period, with the greatest pain sensitivity in the late afternoon33,46 suggesting that circadian rhythms influence behavioral responses. It has also been shown that environmental enrichment attenuates hypersensitivity to mechanical and cold stimuli in mice after nerve injury58. We have attempted to control these environmental factors as much as possible over the past five years, but nonetheless have found that the von Frey thresholds we obtain are lower (more sensitive)18–20,37 compared to values published by other groups7,38,67. Therefore, we asked whether the type of bedding that our animals are housed on sensitizes their behavioral responses to evoked environmental stimuli or in non-reflexive assays for spontaneous pain-like behaviors. Other laboratories have shown that animals show preferences for some bedding materials over others, based on color and texture1,6,29,30,51. We reasoned that the type of bedding that animals are constantly stepping on might affect normal baseline mechanical sensitivity if the bedding components have properties such as sharp edges, splinters, grooves or other surface attributes in their physical properties. In behavioral assays, we routinely test the plantar surface of the hindpaw, which is consistently exposed to the bedding surface. Further, bedding that contains dyes or chemicals might affect the animals’ sensitivity to mechanical, thermal or chemical stimuli. Therefore, we set out to quantitatively determine in an otherwise controlled (to the greatest extent possible) environment, the effects of different bedding types on behavioral responses in mice under normal conditions and after acute and chronic peripheral hindpaw inflammation. We tested evoked behavior to mechanical, heat and cold stimuli as well as spontaneous (non-reflexive) behavior assays for mice housed on different bedding types that are typically used in many animal care facilities.

METHODS

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6 mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) of at least 6 week of age were used and housed for at least two weeks on the specific indicated bedding type at our facility before behavior tests were performed. Prior to our facility receiving the mice, they were housed on a one-to-one mixture of Aspen Sani-Chips® and Aspen Shavings (Northeastern Products Corp) at the Jackson Laboratories. Mice were housed in a 14:10 hour light:dark cycle and were provided with food and water ad libitum. All animals were maintained with experimental protocols approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin and performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bedding Types

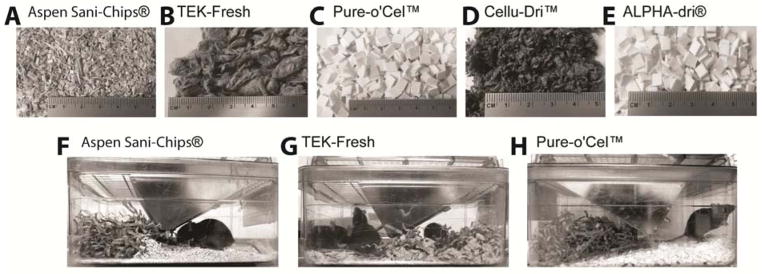

To test differences in behavioral responses we housed the animals on five different bedding types, with Enviro-dri®54 nesting material. The animal facility at our institute typically uses an Aspen wood chip bedding called Sani-Chips® (Fig 1A), which when touched feels somewhat prickly with sharp edges, even though the wood pieces are small. The Aspen chips are dried to about 8% moisture content and then screened to the specifications which include a size range from 8 to 20 mesh of the National Institute of Health28. The Aspen Sani Chips® we use come from P.J. Murphy Forest and Products, and are virtually dust-free, contain no chemical additives or paper sludge, and are not a food source for animals. TEK-Fresh bedding (Fig 1B) is a very soft bedding, which is made of 100% virgin wood pulp, and has the consistency of soft egg cartons22. Importantly, TEK-Fresh is virtually dust-free and does not irritate either human or animal respiratory systems. TEK-Fresh does not contain any silica, resins, or aromatic hydrocarbons that could irritate the animals’ respiratory system22. The third bedding we tested was Pure-o’Cel™ bedding (Fig 1C), which is made out of white ¼″ paper chip squares and is hard with relatively sharp edges. The paper chips offer 74% more surface area than typical squares, which makes the Pure-o’Cel™ bedding more absorptive than other paper square bedding types57. Cellu-Dri™ Soft (Fig 1D), is very soft bedding made out of recycled cellulose fiber. The soft texture of the bedding enhances enrichment of the environment and encourages nest building, Cellu-Dri™ also helps eliminate dust problems as it reduces dust cling on the animals’ coat53. Lastly, the ALPHA-Dri® (Fig 1E) bedding is made of white paper chips that are sanitary and virtually dustless, with paper squares that are bigger than the Pure-o’Cel™ bedding. ALPHA-Dri® is reported to be about ten times more absorbent than other wood chip bedding52 like Aspen bedding. It is comprised of pure, virgin paper cellulose, which is virtually free of confounding contaminants28. We noted that animals nest more readily in the TEK-Fresh bedding as compared to Aspen or Pure-o’Cel™ bedding as shown in photos from animals in our study (Fig 1F–H) and its soft quality is thought to enhance environmental enrichment and encourages nest building1,6,45.

Figure 1.

Bedding materials used for housing mice two weeks prior to behavioral testing. A Aspen Sani Chips® B TEK-Fresh C Pure-o’Cel™ D Cellu-Dri™ Soft E ALPHA-Dri® F Mice housed on Aspen Sani Chips® build small nests out of Enviro-dri®. G Mice housed on TEK-Fresh bedding mix the Enviro-dri® with their bedding to build larger nests. H Mice housed on Pure-o’Cel™ push bedding material away from Enviro-dri® nest to the other side of the cage.

Behavioral Assays

Animals were housed on their respective bedding type for at least two weeks straight before behavioral experiments were performed. For the naïve data set, Figure 2 and Figure 3, the experimenter was not blinded to the bedding type, although the experimenter had no expectations of any group differences or direction of differences. For the inflammation study, animals were injected with Complete Freud’s Adjuvant (CFA) into the plantar paw and the experimenter was blinded to the bedding type and treatment. Behavioral assays were performed on day 2 (Up-Down von Frey and Hargreaves test, with at least 1 hour break between tests, day 4 (cold temperature preference) and day 5 (needle assay) after CFA or vehicle (PBS) injection. Mice were acclimated to their surroundings for one hour before being tested unless otherwise noted. All tests were conducted between 8am and 3 pm. Using the Up-down method the mechanical threshold of the glabrous paw skin was assessed by using a series of calibrated von Frey filaments ranging from 0.38 to 37mN9,14. Since it is not clear whether von Frey Threshold represents an innocuous or noxious stimulus to animals, we performed two assays to assess light touch and one to evaluate noxious responses. First, to assess responsiveness to static punctate force, we used a low intensity 0.68mN von Frey filament, stimulated the plantar hind paw ten times and recorded the number of responses. Second, to evaluate responses to a dynamic innocuous stimulus, we used a cotton swab with the cotton “puffed out” and swiped the plantar surface heal to toes, as previously described18. Each hindpaw was stimulated ten times and the percentage of responses recorded. To assess responses to a frankly noxious mechanical stimulus, we applied a spinal needle tip to the plantar hindpaw, alternating between the paws for a total of 10 times each20,24. The number and type of responses were recorded and categorized as normal response, lifting the paw, licking the paw, flicking the paw, and no response, which were then grouped as moderate (normal response and lifting of the paw), or noxious responses (licking and flicking the paw).

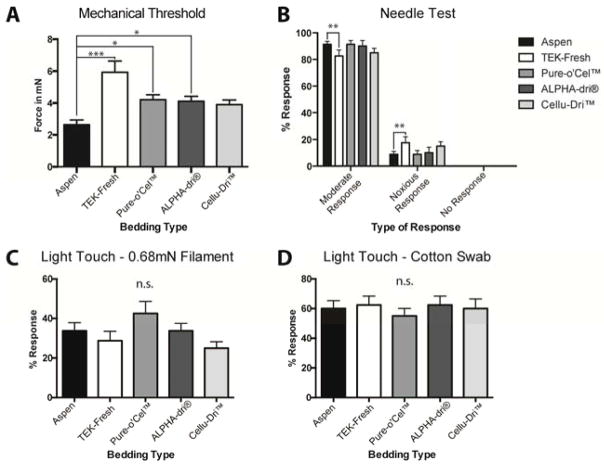

Figure 2.

Bedding material affects mechanical thresholds and noxious responses but not light touch responses. A Mice housed on TEK-Fresh bedding were significantly less sensitive to the von Frey stimulus (P < 0.001). Also Pure-o’Cel™ and ALPHA-Dri® beddings were significantly different from the mice housed on Aspen bedding (P < 0.05). Cellu-Dri™ was not different (p = 0.0764). B Mouse hindpaws were stimulated with a spinal needle. Only mice housed on TEK-Fresh bedding displayed significantly different moderate and noxious responses when compared back to the Aspen-bedding mice (P < 0.01). C The bedding type had no significant effect on the % response when the hindpaw was probed five times using a 0.68mN Filament (P>0.5). D There was also no significant difference in the cotton swab light touch assay between the bedding types (P>0.5). n=8 per group.

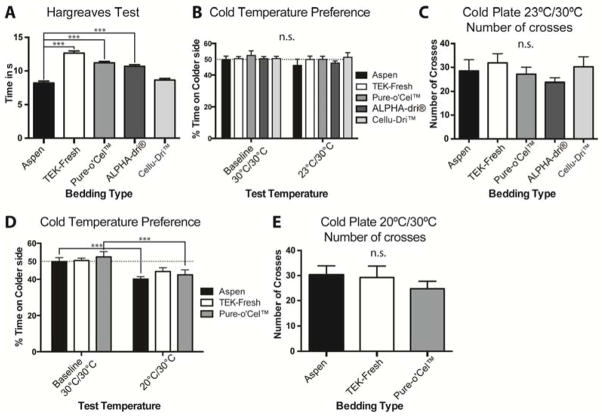

Figure 3.

Bedding types affect thermal behavior assays. A Thermal paw withdrawal threshold latencies are longer for mice housed on TEK-Fresh, Pure-o’Cel™ and ALPHA-Dri® bedding than Aspen bedding (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between mice housed on Cellu-Dri™ and Aspen bedding (P>0.5). B All bedding types show no preference between the sides of the thermal preference plate when both sides are 30°C (“baseline”) as the temperature on one side was decreased to 23°C animals spent an equal amount of time on each side (P>0.5). C Animals crossed the two plates an equal amount of time, there was no significant difference between bedding types (P>0.5). D Animals housed on the three different bedding types spent about 50% on each plate at baseline. Lowering the temperature to 20°C on one p late caused mice housed on Aspen and Pure-o’Cel™ bedding to avoid the colder side (P < 0.01), whereas there was no significant difference between the time that TEK-Fresh animals spent on the colder side versus their baseline (P>0.5). E The bedding type did not affect the number of crosses between different temperature plates (P>0.5). n = 8 per group.

Two thermal assays were performed to test for heat or cold responses. For measuring heat sensitivity (Hargreaves test), animals were allowed to acclimate for at least 30 min on a glass surface before a radiant noxious heat source was applied to the plantar surface of the hindpaw; the latency to paw withdrawal was measured four times for each paw as previously described21. For cold temperature preference assessment, animals were placed in a 13-inch square Plexiglas chamber in which the floor is a dual temperature-controlled metal plate, which allows for independent temperature control on each side (AHP1200-HCP, TECA Corp, Chicago, IL). The apparatus was always placed in the same spot within the behavior testing room and all spatial cues were removed to the best of our capacity. In addition, to ensure that the animals did not simply prefer one side over the other, we randomly altered the side the animal was originally placed on as well as the temperature on each plate. Animals were habituated in the chamber with both plates set at 30°C, one week before the a ctual test was performed. The time spent on each plate, as well as the number of times the animal crossed the midline was recorded during the 5-minute testing period. Baseline measurements were performed first where animals were placed individually into the chamber with both sides set to 30°C. Animals were then tested for preference between either 30°C and 23°C, or 30°C an d 20°C as previously descrived 5,66.

To test non-reflexive behaviors, we also developed a novel, modified conditioned place preference assay for tactile preference in order to determine if the animals exhibited any preference for spending time on the TEK-Fresh or Aspen bedding. The wire meshes and wire bars of a standard conditioned place preference assay (MED-CPP-3013AT, Add-On Three Compartment Place Preference with Auto Guillotine Doors and Light for Mouse; MED associates, Inc., Vt., USA) were covered up with Plexiglas so that the surface of both big chambers was identical, and only the color of the chamber differed (black or white). The two big chambers were connected by a smaller grey neutral space in which mice were acclimated to the apparatus. To determine if the animals had a preference for either one of the big chambers because of the chamber color (black or white), animals were placed in the apparatus and movement was recorded for 30 min. For the actual test, TEK-Fresh bedding or the Aspen bedding was placed on top of the Plexiglas of either the black or white chamber, the movement of the mice was recorded for 30 min, and the time spent on each side was analyzed. A second, non-reflexive behavior, the Wheel Running Assay, was performed to measure running activity over a long time period11. Mice were placed in cages containing a wheel and provided with food and water ad libitum, with either the TEK-Fresh or the Aspen bedding on the cage floor. Mice were acclimated to these cages for three days prior to running, and their wheel running behavior (wheel revolutions per day or minute) was recorded and analyzed over four days of ad lib running.

Hindpaw Inflammation

To generate cutaneous inflammation in the hindpaw, mice were lightly anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and then injected subcutaneously with 30 μL of straight Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA; Sigma) into the hindpaw as previously described37. For acute inflammation, behavioral studies were performed after the second day of inflammation, which corresponds to the time point of greatest mechanical and heat sensitivity37. The von Frey up-down and Hargreaves tests were performed on day two after the injection. Animals were then allowed to rest for a day and were then tested for the cold temperature preference test on day four, followed by the needle test on day five. For chronic inflammation, animals were injected with either 30 μL of straight CFA or PBS and behavior assays (von Frey Up-Down, Hargreaves test and cold temperature preference) were performed 5 weeks later. Five weeks post injection has been shown to be a chronic pain time point for inflammation19, and by 2 weeks after CFA injections, C57BL/6 mice develop rheumatoid arthritis-like pathologic features in their hindpaw10.

Analysis

Data for the up-down test, Hargreaves test, and the light touch assay were analyzed with a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. Responsiveness to the needle test was compared by means of a 2-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni post hoc test to compare responses between the different bedding types. Cold temperature preference test data was analyzed with a Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc test for single temperature comparisons. When baseline preference (30°C/30°C) was compared to the cold preference (30°C /23°C or 30°C /20°C), a 2-way ANOVA was used followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. Mechanical thresholds, the needle assay, cold temperature preference assay, and the Hargreaves test data following CFA were analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA using the Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Results were considered statistically significant when P<0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Bedding type significantly affects mechanical von Frey thresholds

The Medical College of Wisconsin animal facility routinely uses Aspen Sani-Chips®, a wood chip based bedding material (Fig 1A) and Enviro-dri® as nesting material (Fig 1F). Many other facilities such as Jackson Laboratories and Charles River also use Aspen shavings, chips or other wood types for their standard bedding. For this study, the bedding was changed to the indicated new bedding type two weeks before behavior testing. Mice housed on TEK-Fresh build larger nests as compared to mice housed on Aspen bedding (Fig 1F, G) and mice housed on Pure-o’Cel™ push the bedding to the other side of the cage away from the Enviro-dri® nesting material (Fig 1H). When mice were tested for mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds, those housed on Aspen bedding exhibited the lowest von Frey thresholds (~2.5 mN), consistent with von Frey thresholds we have previously reported in other data sets18–20,37. In contrast, von Frey thresholds of mice housed on TEK-Fresh were significantly (nearly 3-fold) higher than those on Aspen bedding (Fig 2A). Animals housed on Pure-o’Cel™ and ALPHA-Dri® also exhibited higher mechanical von Frey thresholds than those on Aspen bedding, ranging between 4 and 4.5mN (Fig 2A). Animals, housed on Cellu-Dri™ exhibited thresholds that were not different from the Aspen bedding, although these animals also showed a trend for higher withdrawal thresholds (p = 0.0764) (Fig 2A). These data indicate that the type of bedding that mice are housed on markedly affects their baseline plantar paw von Frey thresholds.

Noxious and innocuous responses to repeated mechanical stimuli are minimally affected

We then asked whether other categories of mechanical stimuli, either those that are frankly noxious, or likely innocuous, are affected by bedding type. We used the needle test, which appears to be frankly noxious because animals frequently exhibit hyperalgesic responses20,24. In response to plantar paw stimulation with the tip of the needle, we counted and grouped the responses into noxious, moderate responses, and no response. In contrast to von Frey threshold results, we found that animals housed on TEK-Fresh bedding exhibited a higher percentage of intensely noxious responses compared to mice housed on Aspen bedding (Fig 2B). The needle stimulation initiated some type of response in all mice, as no mice showed no responses (Fig 2B). Mice on Cellu-Dri™, Pure-o’Cel™ and ALPHA-Dri® bedding showed no difference in the percentage of noxious or moderate responses compared to Aspen mice (Fig 2B).

To test light touch, we used a dual light touch assay18, for which the static punctate aspect is a very low threshold (0.68 mN) stimulus, and the dynamic aspect is a moving, sweeping “puffed out” cotton swab stroked briskly along the plantar surface. There were no significant differences in responses to either static (Fig 2C) or dynamic (Fig 2D) stimuli between any of the five bedding types tested. These data indicate that the type of bedding used for housing animals affects mechanical behavioral tests, and specifically, von Frey thresholds, which are the most widely used mechanical behavioral sensitivity test, were most greatly affected.

Bedding type affects both heat and cold sensitivity

Next, we asked whether bedding type affects baseline thermal sensitivity using the Hargreaves heat assay21 and a cold temperature preference assay. Mice housed on Aspen bedding were more sensitive to heat stimuli compared to mice housed on other bedding types. The heat paw withdrawal latencies of mice housed on TEK-Fresh, Pure-o’Cel™, and ALPHA-Dri® bedding were longer (less sensitive) than mice housed on Aspen bedding, whereas there was no difference compared to mice housed on Cellu-Dri™ bedding (Fig 3A). We then measured cold sensitivity using the cold place preference test5. Bedding type had no effect on cold temperature preference in either the time spent on a 23°C side or in the number of crosses between the 23°C and 30°C sides (Fig 3B and 3C).

To continue these studies, we reduced the bedding materials to three types: Aspen Sani Chips® because it is the standard at our facility and was associated with the lowest mechanical thresholds, TEK-Fresh because it resulted in the highest mechanical thresholds and one intermediate bedding, Pure-o’Cel™. Because we were uncertain if 23°C was cold enough for the animals to exhibit avoidance, we performed another temperature preference assay with one side held at 20°C (moderately cold) and the other a t 30°C. Animals housed on Aspen and Pure-o’Cel™ bedding spent significantly less time on the colder side, whereas TEK-Fresh housed animals showed no difference (Fig 3D; p= 0.1658). Number of crosses was not affected (Fig 3E). These data indicate that bedding type affects heat and moderately cold sensitivities.

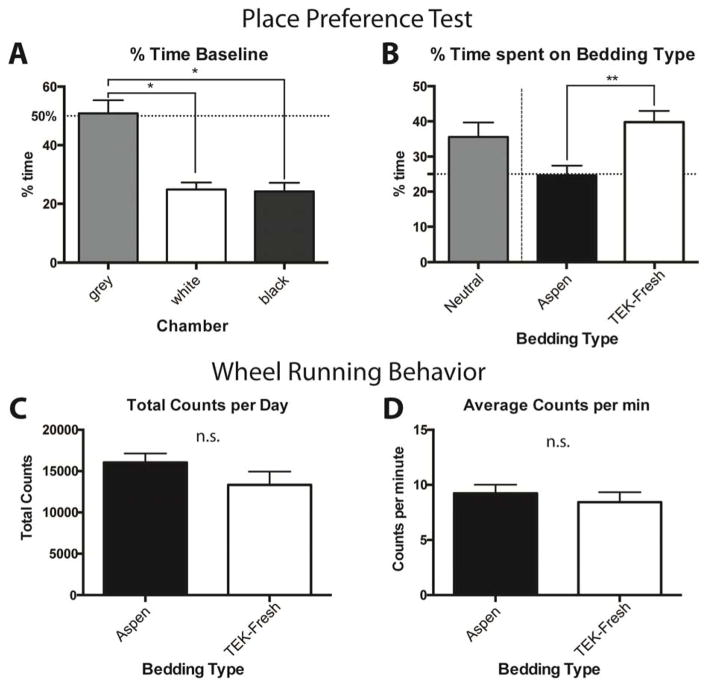

TEK-Fresh is a preferred bedding type

We next asked whether animals exhibit a preference between bedding types when given free choice using a modified conditioned place preference chamber. Mice were housed for at least two weeks on a neutral bedding type (Pure-o’Cel™). First, animals were tested with only a plexi glass floor in the chambers, to determine if there is a side preference based on chamber color. Animals spent equal time in both the white and black side (Fig 4A) but preferred the grey neutral space in the middle to the two sides (Fig 4A). Next, we placed TEK-Fresh or Aspen bedding on top of the plexi glass, and varied the bedding type and the color of the chamber. Animals spent significantly more time on the TEK-Fresh bedding side (approximately 40%) compared to 25% on the Aspen bedding side and approximately 35% of time on the neutral grey space without bedding (Fig 4B). Thus, when given free choice, mice prefer the TEK-Fresh bedding to the Aspen bedding.

Figure 4.

Animals prefer softer bedding materials over wood chips, but general activity levels are unaffected by bedding type. A A modified place preference chamber was used and showed that animals spent an equal time in the white and black chamber (P>0.5) but preferred the small grey middle chamber. B Bedding material was added on top of the plexi glass and animals spent significantly more time in the chamber with the TEK-Fresh bedding than the Aspen bedding (P < 0.01). C The number of wheel revolutions in a cage with a running wheel was recorded for animals housed on either Aspen or TEK-Fresh bedding for 4 days. Total wheel revolution counts per day did not differ between the two bedding types (P>0.5). D The average wheel revolutions per minute did not differ between bedding types (P>0.5). n = 9–10 per group.

In addition, we asked whether animals exhibit different volitional movement activity when housed on different bedding types by measuring activity over 4 days on a wheel running assay. There was no difference in wheel running behavior (total counts per day or average counts per minute) between animals housed on Aspen and the TEK-Fresh bedding (Fig 4C and 4D). Therefore, animals prefer the TEK-Fresh bedding, but spontaneous non-reflexive behaviors appear unaffected by bedding type.

TEK-Fresh bedding results in greatest dynamic range for acute CFA inflammation-induced mechanical hypersensitivity

Since bedding type affects baseline behavioral sensitivity, we further asked whether bedding affects sensitization after an acute tissue injury model. We used the CFA-induced peripheral inflammation model in the hindpaw because it is a key inflammation model used frequently in the pain field37 and because mechanisms underlying inflammatory mechanical sensitization are incompletely understood41. We used the three bedding types that revealed the greatest behavioral differences under baseline conditions: Aspen Sani Chips®, TEK-Fresh and Pure-o’Cel™ bedding. In PBS injected controls, von Frey mechanical thresholds were similar to naïve animals in Figure 2. The TEK-Fresh bedding PBS mice exhibited the highest (least sensitive) thresholds and were significantly different from the Aspen-bedding group (Figure 5A). The Pure-o’Cel™ bedding PBS mice showed significantly higher thresholds than Aspen mice, but lower than TEK-Fresh mice. Interestingly, bedding type did not affect thresholds after CFA injections, as all groups were equally low (~0.2mN), approaching a floor effect (Fig 5A). Because the PBS TEK-Fresh and Pure-o’Cel™ bedding mice had higher baseline von Frey thresholds, these groups exhibited greater mechanical sensitization after CFA, than mice housed on Aspen bedding (Fig 5A).

Figure 5.

Bedding types affect the dynamic range in von Frey mechanical thresholds after acute inflammation. A The dynamic range significantly increased by using a softer bedding Type (TEK-Fresh). Comparing TEK-Fresh and Pure-o’Cel™ PBS animals to CFA animals shows that CFA animals are significantly more sensitive to the von Frey Up-Down threshold test (P < 0.001). Mice housed on Aspen bedding showed a significant difference, however due to the dynamic range decrease the significance was less: P < 0.01 B The paw withdrawal latencies of the Hargreaves test revealed that all animals were equally significantly more sensitive after CFA injections than their PBS-injected controls (P < 0.001) C All animals treated with CFA responded with a higher number of noxious responses to the needle stimulus than animals treated with CFA: Aspen bedding P < 0.001, TEK-Fresh P < 0.01, and Pure-o’Cel™ P < 0.01. CFA treated animals housed on TEK-Fresh responded with a significant increase in their percent responses than Pure-o’Cel™ CFA animals (P < 0.01). D Both treatment types and all three bedding types show no preference for sides of the thermal preference plate at baseline (P>0.5). When the temperature on the test plate was reduced to 20°C, mice of all treatments and bedding types spend less time on the colder side. Aspen PBS, Aspen CFA, and TEK-Fresh PBS were less significantly different (P < 0.05) than Pure-o’Cel™ CFA (P < 0.01). TEK-Fresh CFA and Pure-o’Cel™ PBS differed the most between baseline at 30°C and the reduced temperature 20°C P < 0.001. n = 8–9 per group.

To further investigate nociceptive mechanical hypersensitivity, we used the needle assay. As expected, in all bedding groups, the animals injected with CFA responded with a greater number of noxious responses to the needle stimulus than their PBS controls (solid colored columns compared to striped columns; Fig 5B). During baseline testing, mice housed on TEK-Fresh exhibited a greater hypersensitivity to the needle stimulus than those housed on the Aspen bedding, but after inflammation there was no significant difference between the Aspen CFA and TEK-Fresh CFA, or the Aspen PBS and TEK-Fresh PBS, as shown by the similar number of noxious and moderate responses (Fig 5B; compare black solid to white solid, and compare black striped to white striped in “noxious response”). CFA injected animals housed on TEK-Fresh bedding responded with a significantly higher percentage of noxious responses after the needle stimulus than CFA injected animals housed on Aspen or Pure-o’Cel™ (Fig 5B; white striped versus grey striped bars in “noxious response”). Thus, bedding type affects the magnitude of noxious mechanical sensitization after acute CFA inflammation.

Because the Hargreaves test revealed bedding-associated differences in heat responses in naïve animals, we performed the same assay after PBS and CFA injections. We found that CFA-inflamed animals were more sensitive to heat than PBS controls, regardless of bedding type (Fig 5C). We next asked whether bedding type affects the cold temperature preference assay after inflammation. In contrast to heat sensitivity, acute CFA inflammation did not cause enhanced avoidance of more intense cold temperatures (20°C) (Fig 5D). However, compared to the naïve study, where only Aspen and Pure-o’Cel housed animals avoided the 20°C side (Figure 3D), both PBS and CFA treated animals on all bedding types significantly avoided the colder side after injections of PBS or CFA (Figure 5D). These data suggest that the injection itself may sensitize the animals to cold stimuli. In conclusion neither heat nor cold sensitization after acute CFA inflammation is dependent on bedding type.

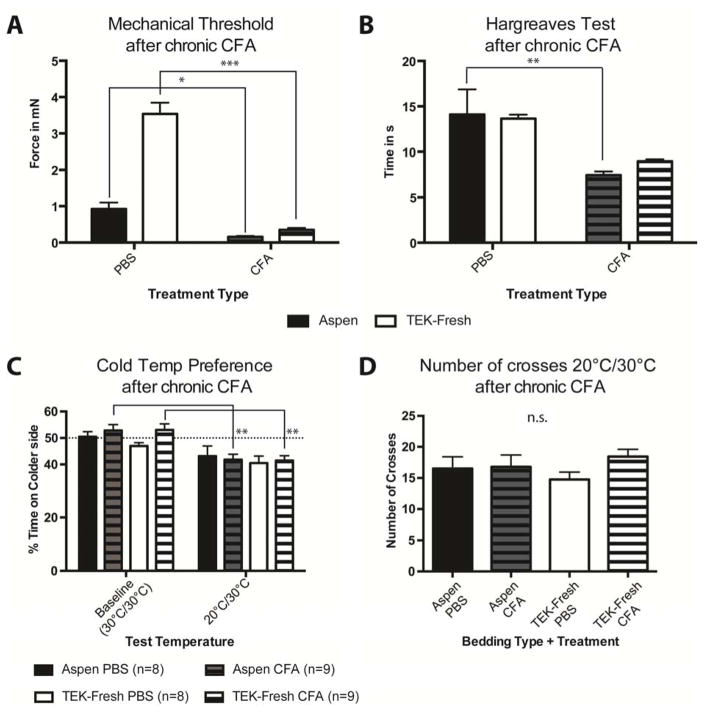

TEK-Fresh bedding increases the dynamic range for mechanical sensitivity and decreases heat sensitivity in chronic inflammation

We next asked whether bedding type affects bona fide chronic inflammation. Behavior assays were performed at baseline and 5 weeks after CFA injections, a time point considered to be chronic19. For this we focused on TEK-Fresh versus Aspen bedding, because TEK-Fresh showed the greatest effect in acute CFA inflammation. Similar to baseline study in Fig 2A and acute inflammation study in Fig 5A, the PBS treated animals housed on Aspen bedding exhibited significantly lower von Frey thresholds than mice housed on TEK-Fresh bedding (Fig 6A). Chronic CFA treated animals housed on either Aspen or TEK-Fresh were significantly more sensitive than their PBS controls (Fig 6A). The dynamic range of the change in paw withdrawal thresholds for animals housed on TEK-Fresh bedding was greater than those housed on Aspen bedding, similar to the difference observed with acute inflammation (Fig 5). Therefore, the magnitude of mechanical sensitization is affected in a similar manner and magnitude after acute or chronic CFA inflammation.

Figure 6.

Effect of bedding type on chronic inflammation. A Aspen versus TEK-Fresh PBS treated animals were significantly more sensitive to the von Frey stimulus (P < 0.001). CFA treated animals housed on Aspen were significantly more sensitive than their PBS controls (P < 0.05). TEK-Fresh animals injected with PBS had significantly higher thresholds than TEK-Fresh animals that received CFA 5 week’s prior (P < 0.001). B Heat withdrawal latencies differed between Aspen PBS and Aspen CFA animals (P < 0.01), however TEK-Fresh animals housed on PBS versus CFA were not different (P > 0.5). C At baseline animals spent about equal times on either plate (P > 0.5). Lowering the temperature of one of the plates to 20°C, revealed that Aspen and TEK-Fresh animals that received CFA injections 5 weeks prior spent significantly less time on the colder plate (P < 0.01). Whereas animals housed on either Aspen or TEK-Fresh bedding that received PBS were not significantly different from baseline (P > 0.5). D The number of crosses between the two plates of the cold temperature preference assay (20°C/30°C test temperature) was not significantly different between bedding types (Aspen or TEK-Fresh) and the treatment type (PBS or CFA) (P > 0.5). (Aspen PBS n=8; Aspen CFA n=9; TEK-Fresh PBS n=8; TEK-Fresh CFA n=9)

We next tested thermal sensitivities during chronic inflammation. Aspen-housed chronic inflamed mice were more sensitive than PBS controls (Fig 6B), but TEK-fresh housed animals showed no significant effect (Fig 6B). In the cold temperature preference assay, chronic CFA mice (striped bars) housed on both Aspen and TEK-Fresh bedding avoided the colder side compared to their baseline preference of side (Fig 6C; striped bars at baseline compared to striped bars at 20°C/30°C). However, the PBS inject ed groups (solid bars) showed no temperature preference for either bedding type (Fig 6C). Activity levels during the 20°C/30°C test were not different for either bedding type or treatment group (Fig 6D). Thus, bedding material affects heat sensitivity but not moderately cold temperature preference in mice after chronic CFA inflammation.

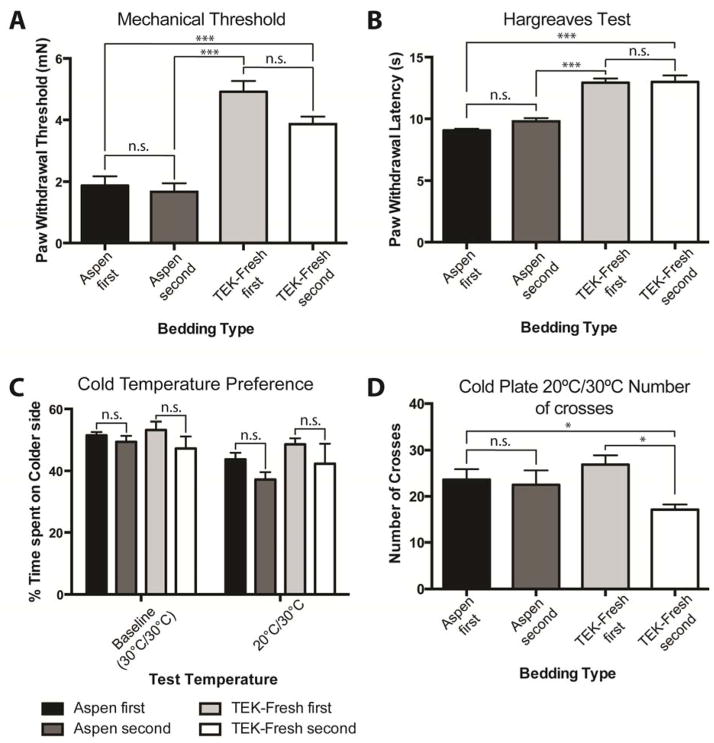

Housing animals for just two weeks on different bedding material affects their mechanical and heat thresholds

To determine whether the effects of bedding material on behaviors that we observed were due to intrinsic differences in the animals assigned to a specific bedding group, or due to effects of the bedding itself, we formed groups in which animals served as their own internal control by testing both bedding types for two weeks, in sequence, on the same animals. One group was housed first on Aspen Sani-Chips® for two weeks and animals were assessed for von Frey thresholds, heat responses and cold temperature preference. The bedding material was then changed to TEK-Fresh and behavior assays were repeated. The second group was first housed on TEK-Fresh bedding and secondly, Aspen bedding. Similar to the initial study group results shown in Figures 2 and 3, animals housed on Aspen bedding had lower paw withdrawal thresholds, and higher heat sensitivities than TEK-Fresh animals, but the order of the bedding did not matter. Housing animals for just two weeks on a different bedding was long enough to induce the differential behavior phenotype. Likewise, there were no differences in time spent on the colder side for the 20°C/30°C temperature preference test when animals were housed on Aspen or TEK-Fresh first (Fig 7C). However mice housed secondly on TEK-Fresh bedding exhibited a significant decrease in the number of crosses between the plates when compared to Aspen first and TEK-Fresh first housed animals (Fig 7D). These results confirm that the differences observed in previous data sets were not due to intrinsic differences of the animals assigned to the different bedding groups, but instead due to environmental/tactile effects caused by housing animals on the different bedding materials.

Figure 7.

Just two weeks of housing on a new bedding material is long enough to affect mechanical and thermal sensitivities. A Paw withdrawal thresholds do not differ between being housed on a bedding first or second (P > 0.5), but thresholds significantly differ between TEK-Fresh versus Aspen Bedding (P < 0.001) B Heat withdrawal latencies do not differ within the bedding type groups (P > 0.5), but they do significantly differ between Aspen and TEK-Fresh bedding (P < 0.001) C Animals spent about 50% of time on each plate at baseline (P > 0.5). When one plate was lowered to 20°C no difference within the bedding type groups was observed (P > 0.5). D Animals housed secondly on TEK-Fresh exhibited significantly lower number of crosses between the 20°C and the 30°C plate, as compared to Aspen First and TEK-Fresh first (P < 0.05). Aspen first numbers of crosses versus Aspen second number of crosses were not significantly different (P > 0.5). n = 8 per group.

DISCUSSION

Here we show that the bedding material that mice are housed on for as short as two weeks affects their baseline mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds, noxious responses to a needle stimulus, and heat sensitivity. Naive mice housed on the widely-used Aspen chips are more sensitive than mice housed on softer, TEK-Fresh bedding and, when given a choice, prefer to spend time on TEK-Fresh material. However, preference for bedding did not affect the animals’ general activity levels, mild cold temperature preference, or light touch sensitivity. While acute (2 day) CFA inflammation induced the same level of mechanical hypersensitivity regardless of bedding type, the dynamic range between inflamed and control cohorts was greatest on TEK-Fresh bedding since baseline thresholds on TEK-Fresh were the least sensitive. No difference was observed between the different bedding groups in two thermal tests, the Hargreaves heat test and the cold temperature preference assay, following acute inflammation. Chronic (5 week) CFA inflammation induced mechanical hypersensitivity, regardless of the bedding type, that was similar to the acute CFA inflammation results. However, TEK-Fresh bedding animals showed no heat sensitivity after chronic CFA compared to Aspen mice.

These data suggest that 1) careful consideration should be used when choosing bedding for somatosensory studies, 2) the default bedding used by an animal care facility may not be ideal for observing changes in mechanical and thermal sensitivity after tissue injury or differences in cohorts of transgenic mice, and 3) importantly, different results reported between laboratories using apparently similar animals, transgenic lines, and injury models may be in part due to different environmental housing parameters such as bedding material.

Bedding materials affect evoked behavior assays, particularly those that rely on detection thresholds

Different bedding materials used for routine housing of animals can affect daily behaviors of mice, such as nesting and sleeping. Further, it has been shown that the particle size of wood chip bedding can affect rat behavior after chronic constriction injury and partial axotomy51. Interestingly, Robinson et al. reported that the von Frey threshold test was robust and not affected by a change in particle size of the bedding. In contrast, in our study, we observed the greatest differences in von Frey thresholds compared to other mechanical, thermal or non-reflexive assays. The difference in studies may due to the fact that the various bedding types used in our study had markedly different textures and composition, from soft (TEK-Fresh and Cellu-Dri™ Soft)22,53, to hard paper squares (ALPHA-Dri® and Pure-o’Cel™52,57) to somewhat sharp and prickly wood chips (Aspen Sani Chips®)47, whereas the Robinson study bedding material differed only in particle size. Or, the difference may be due to the diverse injury models used, nerve injury51 versus inflammation (this study). Furthermore, the three assays that measure the sensitivity of detection (von Frey mechanical threshold tests, the Hargreaves test, and the moderately cold temperature preference assay) were most greatly affected by the bedding material. In comparison, other assays that measure responses to a more sustained or repeated stimulus (needle assay, light touch and mild cold temperature preference) were either mildly influenced or not affected by bedding type.

Why assays that measure detection sensitivity would be more prominently affected than assays involving sustained or repeated stimuli is curious. It is known that sensory systems often undergo a phenomenon of adaptation whereby the nervous system decreases its response to a constant stimulus. Indeed, mechanosensitive ion channels can adapt to stimuli. Hair cell mechanoreceptors respond to sustained mechanical stimuli through current adaptation by closing the transduction channels13,60. Light touch-sensitive neurons respond to touch through activation of Piezo2 and Piezo2 underlies the rapidly inactivating mechanically-gated current in somatosensory neurons12,50. Mechanisms underlying adaptation may occur at the spinal or higher CNS levels. It is possible that mice adapt more readily to a continuous sensory stimulus and therefore respond less to a repeated stimulus. Perhaps TEK-Fresh bedding provides a more continuous stimulus without edges than Aspen bedding which has abrupt, possibly sharp edges, thereby resulting in greater adaptation of animals housed on TEK-Fresh bedding.

It was not surprising to us that bedding types elicited no differences in the wheel running assay, because this assay relies more on skeletal leg muscle activity than on superficial mechanical stimuli to the skin of the plantar foot. Therefore, it appears that bedding type mainly affects assays that depend on tactile input from the hindpaw skin, and particularly on the detection thresholds for a stimulus. Given the marked differences in mechanical thresholds we observed, it is possible that the bedding types with abrupt, possibly sharp edges such as the Aspen bedding induce a continuous “sensitization” of the glabrous paw skin of animals to suprathreshold punctate stimuli, which are also applied directly to the glabrous hindpaw skin.

But at what level of the body does this sensitization occur? Sensitization could occur at the stimulus transduction site in the periphery, at the level of the sensory afferent terminals, the skin, or both. Moreover, sensitization might also ultimately occur at higher levels of the somatosensory circuits within the spinal cord, thalamus, cortex, or descending control pathways. Bedding with abrupt edges may result in increased stimulation of the plantar foot area, which in turn, could lead to differential central sensory processing of an evoked stimulus from that area51.

A variety of primary afferent subtypes detect different properties of tactile to noxious mechanical stimuli, and can be subtyped according to their structural endings, sensitivity thresholds, and response properties. C fibers and slowly adapting Aδ mechanoreceptors (AM) fibers terminate in the skin as free nerve endings, and many of these classes are high threshold mechanical nociceptors3 while some C fibers are low threshold and detect gentle touch40. Sensitization of nociceptive afferents may occur due to persistent activation from the sharp edges of the bedding material that the animals are housed on, potentially resulting in lowered mechanical thresholds compared to animals housed on soft bedding. Future skin nerve electrophysiological recordings would parse out whether the sensitization occurs at the level of the primary afferent and determine which fiber type(s) are affected by the different bedding types32. Bedding material properties may affect sensory processes even down to the molecular and cellular level. For example, if primary afferents are sensitized by bedding, it is possible that ion channels such as Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), TRPV1 or Piezo28,12,34,59 or the signaling cascades that lead to their sensitization are affected4,8,12,15. Thus, molecular studies of sensory transduction molecules may be affected by bedding materials.

Traditionally, peripheral sensory nerve endings have been assumed to be the initial and sole responders to environmental stimuli such as mechanical or temperature stimuli. However, external stimuli first come in contact with the epidermis of the skin before impacting sensory neurons. The epidermis is comprised of approximately 95% keratinocytes, whose primary role is thought to be formation of a protective barrier16. However, because keratinocytes are found in close proximity to sensory nerve terminals in the epidermis, it is possible that they can aid in the signal transduction of external stimuli to sensory neurons. Keratinocytes have been shown to release a variety of chemical substances (ATP, neurotrophins, interleukins, cytokines) that can activate or inhibit sensory neurons42. Therefore, different textures of the bedding materials may activate differential release of these chemical factors from keratinocytes, leading to increased or decreased sensitivity. In addition, the skin is innervated by multiple low-threshold touch receptors. One of those receptors, Meissner’s corpuscles is found specifically in glabrous skin, located superficially at the epidermal-dermal border, and conveys textural information. Another touch receptor is the Merkel cell-neurite complex that encodes the edges and curvatures of objects43. Recent evidence demonstrates that Merkel cells can directly respond to mechanical stimuli and therefore shape the response of slowly adapting type I Aβ fiber afferent terminals to sustained force26,44,62. Therefore another plausible possibility is that the exposure of the glabrous skin to the different textures of the bedding material leads to the sensitization of those receptors and their end organ structures, ultimately affecting the threshold of detection for a stimulus.

Further, it is also possible that the reduced paw withdrawal thresholds observed from animals housed on Aspen bedding is the result of central nervous system (CNS) changes in the spinal cord or higher. Central sensitization occurs when an alteration in the gain of the pain pathway occurs in a way that a given stimulus will cause larger excitatory postsynaptic potentials and a greater number of action potentials in second- or third-order neurons, thereby, leading to greater pain perception35. Continuous activation of free nerve endings and nociceptors has been shown to result in central sensitization in models of tissue injury35,64. Therefore, it is possible that there are long-term changes in the CNS that are elicited by the texture of the bedding material. For example, sharp edges that are initially moderately noxious may become more noxious to the animals after repeated application from continuous treading on the bedding surface in a form of “wind up” in the CNS63,65. This ultimately may result in the lower von Frey thresholds on Aspen bedding observed in our study.

Environmental enrichment can decrease pain behavior

It has been shown previously that mice display a preference for bedding types that are soft and that encourage nest building1,6,45. We observed increased nesting behavior in animals that were housed on TEK-Fresh but did not observe this behavior when animals were housed on any other bedding material (Fig 1F, G, H). This in turn supports results from our bedding preference assay, because animals preferred TEK-Fresh to Aspen bedding when given free choice.

Furthermore, environmental enrichment has been shown to decrease hypersensitivity to mechanical and cold stimuli17,58. Because of its environmental enrichment properties TEK-Fresh may decrease the hypersensitivity to a mechanical stimulus (von Frey force threshold) and therefore explain the higher (less sensitive) von Frey thresholds observed in the TEK-Fresh bedding animals compared to the Aspen-bedding animals. Additionally, it has been shown that olfactory stimuli, such as pheromones of males, or male predators, or male experimenters decrease pain behaviors56. Of note, all experimenters performing behavioral assays in this study were female. The heavy metal or other added chemicals were not different between bedding materials. But because beddings were made of different materials they may smell differently to mice, which may lead to differential behavior outcomes, and a preference for bedding. In summary, the bedding texture, shelter from light, and odorants in bedding are all factors that could influence the animal’s preference for bedding.

Thermal behavior is affected by bedding type at baseline but not after inflammation

We observed that both the heat and moderately cold (20°C) preference assays were affected by the bedding material, but not the mild cold (23°C) preference assay. Keratinocytes express thermal receptors such as the warm activated ion channels TRPV3 and TRPV4 and can release chemical factors such as ATP42. The mechanical stimulation by the bedding type might sensitize sensory neurons at baseline before the thermal assay is conducted, and therefore lead to the different results in the thermal assays. The acute (2 day) inflammation study revealed a PBS-mediated sensitization effect in both the Hargreaves test and the cold temperature preference test. However, PBS injection did not affect the mechanical behavior assays (Needle, Light Touch, and von Frey threshold test) results. Both treatments (CFA and PBS) require injection of a compound into the paw, and PBS injection alone into the skin might cause some acute inflammation or sensitization. Furthermore, both of these tests involve a thermal stimulus that is applied over a greater surface area of paw skin (stimulation of more receptive fields) than the probing of the hindpaw with the von Frey filaments or a spinal needle. It is likely that when we mechanically probe the hindpaw that the injection site is not probed. However in the way our current thermal tests are done, activation of the injection site cannot be avoided.

Bedding material alters mechanic thresholds and heat sensitivity after chronic inflammation of the mouse paw

Most animal studies focus on the acute inflammation time points, typically within a week of induction of inflammation. However, a much greater problem clinically is chronic pain, which typically is characterized as pain lasting for at least 3 months27 and often patients are first seen by a physician months to a year after pain was first noticed. The CFA model of inflammation has been widely used in acute inflammation36,37,49, however, it can also be used for chronic inflammation (3 or more weeks after injection) and shares characteristics of CFA-induced arthritis19,39,61. We observed that chronic inflammation (5 weeks post CFA injection) had the same effect on mechanical sensitization as acute (2 day) inflammation. Changing the bedding type to TEK-Fresh increased the dynamic range and therefore, an increase in the magnitude of sensitization was observed.

Previous research has shown that the heat hyperalgesia persists for approximately one week and returns to baseline two weeks after CFA injection in wild type mice31. Our chronic CFA data confirmed those findings for animals housed on TEK-Fresh bedding; because no significant difference was found between PBS and CFA treated animals. However animals housed on Aspen bedding still had a strong heat sensitization phenotype 5 weeks after CFA injections as compared to their PBS control. This could be explained by the fact that the Aspen bedding might cause continuous sensitization through the mechanical stimulation, therefore resulting in lower heat withdrawal thresholds, than mice housed on the softer, TEK-Fresh bedding. Or, it may suggest that the environmental enrichment due to TEK-Fresh bedding decreased the heat hyperalgesia in those mice. This result could be very important for researchers that wish to study the pure effect of heat hyperalgesia, for which the use of a softer bedding type would be beneficial. The fact that the cold temperature preference behavior was unaffected by the bedding type could be due to the fact that different ion channels sense high and low temperatures and therefore differential sensitization of these channels can occur due to chronic CFA inflammation. For example TRPA1 and TRPM8 have been shown to sense cold temperature while TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPV4 sense warmer temperatures2. Ultimately, this inflammation study revealed that changing the bedding type not only for acute inflammation studies, but also for chronic inflammation studies could be beneficial for investigators.

CONCLUSION

It has long been known that different bedding materials can affect the wellbeing and sexual behavior of mice25,28,48,55, but the potential effects on the evoked and non-evoked somatosensory behavior assays have been little studied. Through the combination of a variety of evoked and non-evoked assays, and acute and chronic tissue inflammation, we have shown that the bedding type can markedly affect animal behavior. It is important to note that facilities, such as Jackson laboratories or Charles River, where many US researchers obtain their animals from, use Aspen chips and shavings or other wood chip beddings as their standard bedding type, and therefore researchers could receive animals that are already sensitized prior to performing any behavioral studies. That said, our study shows that housing for just two weeks on TEK-Fresh bedding reduces the baseline sensitivity of the mice. Furthermore, because the bedding material markedly affected the behavioral assays, it is possible that the bedding type can also affect somatosensory signaling at the molecular, cellular and physiological levels. Considering the increasing costs of purchasing, breeding, and housing animals, coupled with the ethical considerations of using animal models, these results indicate that housing animals on a softer bedding type may have strong utility to somatosensory researchers by decreasing the time, money, and number of animals needed for behavioral assays.

Perspective.

These findings indicate that the bedding type that animals are routinely housed on can markedly affect the dynamic range of mechanical and heat behavior assays under normal and tissue injury conditions. Among beddings tested, TEK-Fresh bedding resulted in the least sensitive baseline thresholds for mechanical and thermal stimuli and the greatest dynamic range after tissue injury. Therefore, careful consideration should be used when selecting routine cage bedding material for animals that will be tested in behavioral somatosensory assays.

Highlights.

Bedding material affects evoked baseline behavioral mechanical and heat thresholds

Bedding affects dynamic range of mechanical thresholds after acute CFA inflammation

Chronic CFA reveals effects of bedding on mechanical and heat thresholds

Non-reflexive ongoing behaviors are unaffected by bedding materials

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Andy D. Weyer, Katherine J. Zappia and Ashley M. Reynolds who provided advice on data analysis, organization and direction of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Diana Bautista for insightful discussions in initiating the project and interpretation of data and Dr. Kenneth Allen for his valuable feedback in animal care and bedding material sources. The research reported in this manuscript was supported by NIH grants NS040538 and NS070711 to CLS. Furthermore, the authors would also like to thank the “Research and Education Initiative Fund, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin” for allowing us to use the conditioned place preference apparatus in the Medical College of Wisconsin behavior core.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The research reported in this manuscript was supported by NIH grants NS040538 and NS070711 to CLS. Furthermore, partial support for this work was provided by the Research and Education Component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ago A, Gonda T, Takechi M, Takeuchi T, Kawakami K. Preferences for paper bedding material of the laboratory mice. Exp Anim. :157–612002. doi: 10.1538/expanim.51.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baez D, Raddatz N, Ferreira G, Gonzalez C, Latorre R. Gating of Thermally Activated Channels. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Pain. Cell. 2009;139:267–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bautista DM, Jordt S-E, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell. 2006;124:1269–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bautista DM, Siemens J, Glazer JM, Tsuruda PR, Basbaum AI, Stucky CL, Jordt S-E, Julius D. The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature. 2007;448:204–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blom HJ, Van Tintelen G, Van Vorstenbosch CJ, Baumans V, Beynen aC. Preferences of mice and rats for types of bedding material. Lab Anim. 1996;30:234–44. doi: 10.1258/002367796780684890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonin RP, Bories C, De Koninck Y. A simplified up-down method (SUDO) for measuring mechanical nociception in rodents using von Frey filaments. Mol Pain Molecular Pain. 2014;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caterina MJ, Schumacher Ma, Tominaga M, Rosen Ta, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chillingworth NL, Donaldson LF. Characterisation of a Freund’s complete adjuvant-induced model of chronic arthritis in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;128:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobos EJ, Ghasemlou N, Araldi D, Segal D, Duong K, Woolf CJ. Inflammation-induced decrease in voluntary wheel running in mice: A nonreflexive test for evaluating inflammatory pain and analgesia. Pain International Association for the Study of Pain. 2012;153:876–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford BYaC, Evans MG, Fettiplace R. Activation and Adaptation of Transducer currents in Turtle Hair Cells. 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon W. Efficient Analysis of Experimental Observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:441–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubin AE, Schmidt M, Mathur J, Petrus MJ, Xiao B, Coste B, Patapoutian A. Inflammatory signals enhance piezo2-mediated mechanosensitive currents. Cell Rep The Authors. 2012;2:511–7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs E. Keratins and the Skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:123–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabriel AF, Paoletti G, Della Seta D, Panelli R, Marcus MaE, Farabollini F, Carli G, Joosten EaJ. Enriched environment and the recovery from inflammatory pain: Social versus physical aspects and their interaction. Behav Brain Res Elsevier BV. 2010;208:90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrison SR, Dietrich A, Stucky CL. TRPC1 contributes to light-touch sensation and mechanical responses in low-threshold cutaneous sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:913–22. doi: 10.1152/jn.00658.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrison SR, Stucky CL. Contribution of Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 to Chronic Pain in Aged Mice With Complete Freund’s Adjuvant – Induced Arthritis. 2014;66:2380–90. doi: 10.1002/art.38724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrison SR, Weyer AD, Barabas ME, Beutler Ba, Stucky CL. A gain-of-function voltage-gated sodium channel 1.8 mutation drives intense hyperexcitability of A- and C-fiber neurons. Pain International Association for the Study of Pain. 2014;155:896–905. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harlan. 7099 TEK-Fresh [Internet] [cited 2015 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.harlan.com/products_and_services/research_models_and_services/bedding_and_enrichment_products/contact_bedding/tekfresh.hl.

- 23.Hillery Ca, Kerstein PC, Vilceanu D, Barabas ME, Retherford D, Brandow aM, Wandersee NJ, Stucky CL. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 mediates pain in mice with severe sickle cell disease. Blood. 2011;118:3376–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan Q, Sapunar D, Modric-Jednacak K, McCallum JB. Detection of neuropathic pain in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:476–87. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horn MJ, Hudson SV, Bostrom La, Cooper DM. Effects of cage density, sanitation frequency, and bedding type on animal wellbeing and health and cage environment in mice and rats. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2012;51:781–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikeda R, Cha M, Ling J, Jia Z, Coyle D, Gu JG. Merkel cells transduce and encode tactile stimuli to drive Aβ-afferent impulses. Cell Elsevier. 2014;157:664–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Association for the Study of Pain TF on T. Classification of chronic pain. Aust Dent J. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson E, Demarest K, Eckert WJ, Nadav T, Cates LN, Howard H, Roberts AJ. Aspen shaving versus chip bedding: effects on breeding and behavior. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0023677214553320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawakami K, Shimosaki S, Tongu M, Kobayashi Y, Nabika T, Nomura M, Yamada T. Evaluation of bedding and nesting materials for laboratory mice by preference tests. Exp Anim. 2007;56:363–8. doi: 10.1538/expanim.56.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawakami K, Xiao B, Ohno R, Ferdaus MZ, Tongu M, Yamada K, Yamada T, Nomura M, Kobayashi Y, Nabika T. Color Preferences of Laboratory Mice for Bedding Materials: Evaluation Using Radiotelemetry. Exp Anim. 2012;61:109–17. doi: 10.1538/expanim.61.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keeble J, Russell F, Curtis B, Starr A, Pinter E, Brain SD. Involvement of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in the vascular and hyperalgesic components of joint inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3248–56. doi: 10.1002/art.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koltzenburg M, Stucky CL, Lewin GR. Receptive properties of mouse sensory neurons innervating hairy skin. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1841–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konecka AM, Sroczynska I. Circadian rhythm of pain in male mice. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;31:809–10. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwan KY, Allchorne AJ, Vollrath Ma, Christensen AP, Zhang D-S, Woolf CJ, Corey DP. TRPA1 contributes to cold, mechanical, and chemical nociception but is not essential for hair-cell transduction. Neuron. 2006;50:277–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central Sensitization: A Generator of Pain Hypersensitivity by Central Neural Plasticity. J Pain Elsevier Ltd. 2009;10:895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H, Iida T, Mizuno A, Suzuki M, Caterina MJ. Altered thermal selection behavior in mice lacking transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1304–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4745.04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lennertz RC, Kossyreva Ea, Smith AK, Stucky CL. TRPA1 mediates mechanical sensitization in nociceptors during inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang DY, Li X, Shi X, Sun Y, Sahbaie P, Li WW, Clark JD. The complement component C5a receptor mediates pain and inflammation in a postsurgical pain model. Pain International Association for the Study of Pain. 2012;153:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu HX, Bin Tian J, Luo F, Jiang YH, Deng ZG, Xiong L, Liu C, Wang JS, Han JS. Repeated 100 Hz TENS for the treatment of chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia and suppression of spinal release of substance P in monoarthritic rats. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2007;4:65–75. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Löken LS, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F, Olausson H. Coding of pleasant touch by unmyelinated afferents in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:547–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lolignier S, Eijkelkamp N, Wood JN. Mechanical allodynia. Pflugers Arch. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1532-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lumpkin Ea, Caterina MJ. Mechanisms of sensory transduction in the skin. Nature. 2007;445:858–65. doi: 10.1038/nature05662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lumpkin EA, Marshall KL, Nelson AM. The cell biology of touch. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:237–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maksimovic S, Nakatani M, Baba Y, Nelson AM, Marshall KL, Wellnitz Sa, Firozi P, Woo S-H, Ranade S, Patapoutian A, Lumpkin Ea. Epidermal Merkel cells are mechanosensory cells that tune mammalian touch receptors. Nature. 2014;509:617–21. doi: 10.1038/nature13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manser CE, Broom DM, Overend P, Morris TH. Investigations into the preferences of laboratory rats for nest-boxes and nesting materials. Lab Anim. 1998;32:23–35. doi: 10.1258/002367798780559365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minett MS, Eijkelkamp N, Wood JN. Significant Determinants of Mouse Pain Behaviour. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy PJ. Forest Products: Aspen Sani-Chips® [Internet] [cited 2015 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.pjmurphy.net/index.php/animal-bedding#ab5.

- 48.Periodicals W, Tanaka T, Ogata A, Inomata A, Nakae D. Effects of Different Types of Bedding Materials on Behavioral Development in Laboratory CD1 Mice (Mus musculus) 2014;401:393–401. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.21129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrus M, Peier AM, Bandell M, Hwang SW, Huynh T, Olney N, Jegla T, Patapoutian A. A role of TRPA1 in mechanical hyperalgesia is revealed by pharmacological inhibition. Mol Pain. 2007;3:40. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ranade SS, Woo SH, Dubin aE, Moshourab Ra, Wetzel C, Petrus M, Mathur J, Bégay V, Coste B, Mainquist J, Wilson aJ, Francisco aG, Reddy K, Qiu Z, Wood JN, Lewin GR, Patapoutian a. Piezo2 is the major transducer of mechanical forces for touch sensation in mice. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson I, Dowdall T, Meert TF. Development of neuropathic pain is affected by bedding texture in two models of peripheral nerve injury in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shepherd Specialty Papers: ALPHA-dri® [Internet] [cited 2015 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.ssponline.com/alpha_dri.htm.

- 53.Shepherd Specialty Papers: Cellu-Dri™ Soft [Internet] [cited 2015 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.ssponline.com/cellu_dri.htm.

- 54.Shepherd Specialty Papers: Enviro-dri® [Internet] [cited 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.ssponline.com/enviro_dri.htm.

- 55.Smith E, Stockwell JD, Schweitzer I, Langley SH, Smith AL. Evaluation of cage micro-environment of mice housed on various types of bedding materials. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2004;43:12–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorge RE, Martin LJ, Isbester Ka, Sotocinal SG, Rosen S, Tuttle AH, Wieskopf JS, Acland EL, Dokova A, Kadoura B, Leger P, Mapplebeck JCS, McPhail M, Delaney A, Wigerblad G, Schumann AP, Quinn T, Frasnelli J, Svensson CI, Sternberg WF, Mogil JS. Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nat Methods. 2014;11:629–32. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The Andersons Lab Bedding: Pure o’Cel™ [Internet] [cited 2015 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.andersonslabbedding.com/irradiated/pure-ocel-pb/

- 58.Vachon P, Millecamps M, Low L, Thompsosn SJ, Pailleux F, Beaudry F, Bushnell CM, Stone LS. Alleviation of chronic neuropathic pain by environmental enrichment in mice well after the establishment of chronic pain. Behav Brain Funct Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2013;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vilceanu D, Stucky CL. TRPA1 mediates mechanical currents in the plasma membrane of mouse sensory neurons. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vollrath Ma, Kwan KY, Corey DP. The Micromachinery of Mechanotransduction in Hair Cells. 2010:339–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitehouse MW. Adjuvant arthritis 50 years on: The impact of the 1956 article by C. M. Pearson, “Development of arthritis, periarthritis and periostitis in rats given adjuvants. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:133–8. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woo S-H, Ranade S, Weyer AD, Dubin AE, Baba Y, Qiu Z, Petrus M, Miyamoto T, Reddy K, Lumpkin Ea, Stucky CL, Patapoutian A. Piezo2 is required for Merkel-cell mechanotransduction. Nature Nature Publishing Group. 2014;509:622–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woolf CJ, Thompson SWN. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991;44:293–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90100-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain International Association for the Study of Pain. 2011;152:S2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Woolf CJ. Windup and central sensitization are not equivalent [editorial]. [Review] [51 refs] Pain. 1996;66:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zappia KJ, Garrison SR, Hillery Ca, Stucky CL. Cold hypersensitivity increases with age in mice with sickle cell disease. Pain International Association for the Study of Pain. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang ZJ, Cao DL, Zhang X, Ji RR, Gao YJ. Chemokine contribution to neuropathic pain: Respective induction of CXCL1 and CXCR2 in spinal cord astrocytes and neurons. Pain International Association for the Study of Pain. 2013;154:2185–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]