Abstract

Eukaryotic cells coordinate growth with the availability of nutrients through mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), a master growth regulator. Leucine is of particular importance and activates mTORC1 via the Rag GTPases and their regulators GATOR1 and GATOR2. Sestrin2 interacts with GATOR2 and is a leucine sensor. We present the 2.7-Å crystal structure of Sestrin2 in complex with leucine. Leucine binds through a single pocket that coordinates its charged functional groups and confers specificity for the hydrophobic side chain. A loop encloses leucine and forms a lid-latch mechanism required for binding. A structure-guided mutation in Sestrin2 that decreases its affinity for leucine leads to a concomitant increase in the leucine concentration required for mTORC1 activation in cells. These results provide a structural mechanism of amino acid sensing by the mTORC1 pathway.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) protein kinase is a major growth-regulator that coordinates cell anabolism and catabolism with the availability of key nutrients like amino acids (1–3). Among the amino acids, leucine is of particular interest due to its ability to promote important physiological phenomena, including muscle growth and satiety (4–6), in large part through activation of mTORC1 (7, 8). However, the biochemical mechanism of leucine sensing by the mTORC1 pathway has remained elusive.

While growth factors, energy, and other inputs signal to mTORC1 primarily through the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)-Rheb axis (9–11), amino acids act by regulating the nucleotide state of the heterodimeric Rag guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) and promoting the localization of mTORC1 to lysosomes, its site of activation (12–14). Lysosomal amino acids including arginine are thought to signal to the Rags through a lysosomal membrane associated complex consisting of the v-ATPase (15), Ragulator complex (16), and the putative arginine sensor SLC38A9 (17, 18). Cytosolic leucine, however, signals to the Rags through a distinct pathway consisting of a pentameric protein complex of unknown function called GATOR2, and GATOR1, the GTPase-Activating protein (GAP) for RagA and RagB (19, 20).

Proteomic studies have identified the Sestrins as GATOR2-interacting proteins that inhibit mTORC1 only in the absence of amino acids (21, 22). Subsequent in vitro studies demonstrated that the Sestrin2-GATOR2 interaction is sensitive specifically to leucine, which binds Sestrin2 with a dissociation constant (Kd) of approximately 20 μM. Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK)-293T cells expressing a Sestrin2 mutant that cannot bind leucine fail to activate mTORC1 in response to leucine, suggesting that Sestrin2 is the primary leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway in these cells (20). However, Sestrin2 shares no sequence similarity with known amino acid binding domains, raising the question of how this protein can detect leucine and signal its presence to mTORC1.

Here, we present the structure of human Sestrin2 in complex with leucine, revealing in atomic detail the mechanism of leucine sensing by the mTORC1 pathway.

Structure of leucine-bound Sestrin2

To understand how Sestrin2 detects leucine, we expressed and purified full-length human Sestrin2 from E. coli and verified binding to leucine in vitro by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) (23, Fig. S1). Although we were unable to obtain crystals of Sestrin2 alone, incubation of the protein with leucine allowed formation of crystals containing leucine-bound Sestrin2 that diffracted to 2.7-Å resolution. We solved the structure using single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) with selenomethionine-derivatized protein and refined the model against the native data to a final Rwork/Rfree of 19.6%/22.3% (Table S1). Sestrin2 crystallized in a cubic space group containing five copies per asymmetric unit.

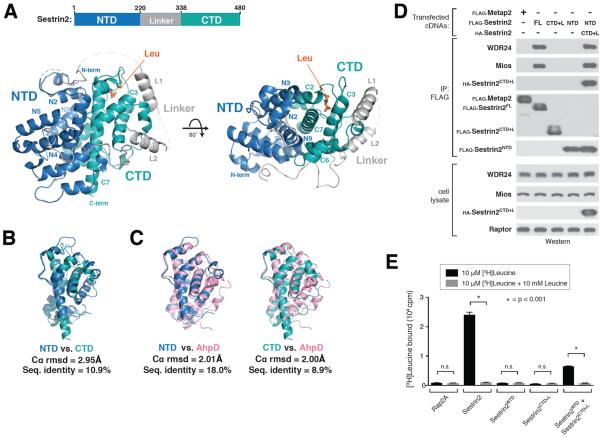

Sestrin2 is a 55 kDa, monomeric, all α-helical, globular protein that contains distinct N-terminal [NTD, residues 66–220] and C-terminal [CTD, residues 339–480] domains connected by a partially disordered, partially helical linker region [Linker, residues 221–338] (Fig. 1A). The N-terminal 65 residues of the protein appear disordered and were not observed in our structure. Electron density map analysis revealed the presence of a single leucine molecule bound to Sestrin2 in the C-terminal domain (Fig 2A).

Figure 1. Structure of leucine-bound Sestrin2.

A) Two views of human Sestrin2 are shown as ribbon diagrams, with the N-terminal (NTD), Linker, and C-terminal (CTD) domains colored in blue, gray, and teal respectively. The bound leucine molecule is shown in orange. Disordered regions not present in the crystal structure (1–65, 242–255, 272–280, 296–309) are shown as dashed lines.

B) Structural superposition of Sestrin2 NTD (blue, residues 66–220) and CTD (teal, residues 339–480).

C) Structural superposition on Sestrin2 NTD (blue) and CTD (teal) with a R. eutropha AhpD dimer (pink, PDB ID: 2PRR)

D) Immunoprecipitation of N- and C- terminal fragments of Sestrin2. HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with FLAG-metap2, FLAG-Sestrin2 full length (FL), FLAG-Sestrin2-NTD (N-terminal domain, 1–220), FLAG-Sestrin2-CTD+L (C-terminal domain plus Linker, 220–480) or both Flag-Sestrin2-NTD and HA-Sestrin2-CTD+L were starved for amino acids for 50 minutes. FLAG-immunoprecipitates were prepared from cell lysates. Immunoprecipitates and lysates from one representative experiment were analyzed by immunoblotting for indicated proteins. WDR24 and Mios were used as representative GATOR2 components.

E) [3H]Leucine binding assay using N- and C-terminal fragments of Sestrin2. FLAG-immunoprecipitates prepared from HEK-293T cells transiently expressing indicated proteins were used as described in the methods. Unlabeled leucine was used as a competitor where indicated. Values are Mean ± SD for 3 technical replicates from one representative experiment. Two-tailed t tests were used for comparison between two groups.

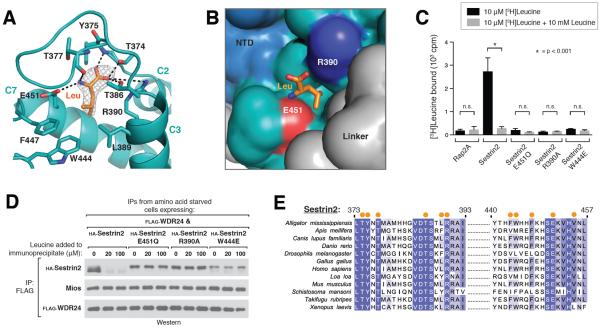

Figure 2. Recognition of leucine by Sestrin2.

A) Close-up view of the leucine binding pocket in Sestrin2, focusing on the bound leucine (shown in orange) together with its 2Fo-Fc electron density map calculated and contoured at 1.5σ from an omit map lacking leucine and all pocket residues. Predicted hydrogen bonds or salt-bridges are shown as black dashed lines. Helix numbers are labeled as in 1A.

B) Surface representation of leucine-bound Sestrin2, focusing on the leucine binding pocket. The bound leucine is represented as a stick model (orange). Residues 373–387 are omitted to allow visibility of the pocket. Residue Glu451, which contacts the amine of leucine is shown in red, and Arg390 which contacts the carboxyl of leucine is shown in blue. The domains of Sestrin2 are colored as in 1A.

C) Binding of the E451Q, R390A and W444E mutants of Sestrin2 to leucine. HA-immunoprecipitates prepared from HEK-293T cells transiently expressing indicated HA-tagged proteins were used in binding assays with [3H]Leucine. Binding was analyzed as in 1E.

D) Effect of leucine on the interactions of Sestrin2 E451Q, R390A or W444L with GATOR2. FLAG-immunoprecipitates were prepared from cells stably expressing FLAG-WDR24 and transiently expressing the indicated HA-tagged Sestrin2 constructs. The immunoprecipitates were treated with the indicated concentrations of leucine and analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins.

E) Multiple Sequence Alignment of Sestrin2 homologs from various organisms. Positions of residues contacting leucine are indicated with orange dots. Positions are colored white to blue according to increasing sequence identity.

The N- and C-terminal domains of Sestrin2 appear to be structurally similar and superpose well, with a root mean square deviation (rmsd) of ~3.0 Å over 55 aligned Cα positions, despite a low sequence identity of 10.9% (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the two domains make extensive contacts with each other, primarily through the two core hydrophobic helices N9 and C7, burying 1,872 Å2 of surface area (Fig.1A).

A small region in the N terminus of Sestrin2 contains weak sequence similarity to the bacterial alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD (24). Analysis of our structure with the NCBI Vector Alignment Search Tool (VAST, 25) showed that Sestrin2 shares a common fold with the carboxymucolactone decarboxylase (CMD) protein family, consisting of bacterial γ-CMD as well as AhpD (pfam: PF02627). Despite low sequence similarity, Sestrin2 strongly resembles an AhpD homodimer, with each half of Sestrin2 matching a single AhpD molecule (Fig. 1C, S2A). The N- and C-terminal domains both superpose well with R. eutropha AhpD, with rmsd's of ~2.0 Å over 129 and 101 Cα's, respectively. Thus, Sestrin2 structurally resembles an intra-molecular homo-dimer of two CMD-like domains, despite extensive divergence in the primary sequence.

To test the importance of the intra-molecular contacts between the two domains of Sestrin2, we expressed the FLAG-tagged N- and C- terminal halves either alone or together as separate polypeptides and performed co-immunoprecipitation analysis. Although neither domain alone bound GATOR2, the separated halves, when expressed together, bound strongly to both each other and to GATOR2 (Fig. 1D). Similarly, although neither half of Sestrin2 alone bound to leucine, the co-expressed halves did bind leucine (Fig. 1E). Therefore, the N- and C- terminal domains of Sestrin2 interact stably with each other and are both required for the interactions with GATOR2 as well as leucine.

In addition to its role as a leucine sensor and GATOR2 inhibitor, Sestrin2 has been reported to have peroxiredoxin-reductase activity, based in large part on its weak sequence similarity to bacterial AhpD, which does have this activity (24). However, other groups have failed to reproduce this finding (26). The active site of AhpD contains two cysteines, both of which are required for its catalytic activity (26, 27). Superposing our Sestrin2 structure with AhpD confirms previous reports (24, 26) that only one of these active site residues is present in the N-terminal half of Sestrin2 (Cys125) whereas both are absent from the C-terminal half (Fig. S2B), suggesting that Sestrin2 either does not reduce peroxiredoxins, or does so through an entirely different mechanism than does AhpD.

Sestrin2 is also reported to inhibit the mTORC1 pathway by directly acting as a guanine-nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) for RagA and RagB through a motif consisting of Arg419, Lys422, and Lys426 (28). However, in our structure two of these three residues (Lys422 and Lys426) are buried (Fig. S2C), and Sestrin2 shows no structural similarity to known GDI proteins.

Recognition of leucine by Sestrin2

Sestrin2 binds leucine through a single pocket formed at the intersection of helices C2, C3, and C7 in the C-terminal domain. Charged residues Glu451 and Arg390 form two sides of the pocket and anchor leucine in place through salt bridges with the free amine and carboxyl groups, respectively (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, helix L1 in the Linker region packs against side of the pocket via residue Leu261 (Fig. S3A), sealing side of the pocket. This is consistent with mutagenesis studies that identified Glu451 and Leu261 as critical for leucine binding (20). Meanwhile, the isopropyl side chain of the bound leucine points down towards the hydrophobic base of the pocket, forming extensive van der Waals contacts with residues Leu389, Trp444, and Phe447 (Fig. 2, A and B). The depth and overall hydrophobicity of this pocket floor make it well suited to accommodate leucine (Fig. 2B).

To test the importance of these protein-ligand interactions, we generated a series of Sestrin2 leucine-pocket mutants. Disrupting the electrostatic coordination of the free amine by switching a single oxygen atom in Glu451 to nitrogen (E451Q) resulted in a complete loss of leucine binding, as did eliminating the interaction between Arg390 and the free carboxyl (R390A, Fig. 2C). In addition, although leucine readily triggered dissociation of the wild-type Sestrin2-GATOR2 complex, both the E451Q and R390A mutants remained constitutively bound to GATOR2 even in the presence of leucine (Fig. 2D). The hydrophobic integrity of the pocket floor is also critical, as insertion of a single charged residue (W444E) was sufficient to abolish any detectable interaction with leucine (Fig. 2, C and D). Consistent with an essential role for these residues in leucine sensing, a multiple sequence alignment of Sestrin homologs showed that both Glu451 and Arg390 are strictly conserved in Sestrin proteins across phylogenetically diverse organisms, as is the hydrophobic nature of the pocket floor (Fig. 2E).

These results provide a molecular explanation for how the Sestrin2-mTORC1 pathway specifically detects leucine and not other amino acids. Although Glu451 and Arg390 likely interact with any amino acid containing free amine and carboxyl groups, the hydrophobic base of the pocket excludes all charged and polar amino acids. Furthermore, large hydrophobic residues such as phenylalanine will clash with Trp444 in the pocket floor, whereas small aliphatic amino acids such as alanine or valine will fail to make favorable van der Waals contacts. Thus, only leucine and the structurally similar amino acids isoleucine and methionine interact appreciably. This is consistent with the finding that only leucine and to a much lesser extent isoleucine and methionine disrupt the Sestrin2-GATOR2 interaction in vitro (20).

Interestingly, the corresponding region in the NTD of Sestrin2 is filled by protein side chains and cannot accommodate leucine (Fig. S3B). However, the position of key residues including Trp444 and Glu451 are conserved in the NTD “pocket” (Trp189 and Glu193), and a leucine side chain contributed by Leu107 occupies the same position as the bound leucine in the CTD (Fig S3B).

A lid-latch mechanism is required for leucine binding by Sestrin2

In addition to contacting the charged sides and hydrophobic base of the pocket, a “lid” formed by a loop connecting helices C2 and C3 encloses the top of the leucine such that it is completely buried within the structure (Fig. 2A). Three highly conserved threonine residues (Thr374, Thr377 and Thr386) are positioned directly above the leucine and help coordinate the free amine and carboxyl groups, locking the ligand in place (Fig. 2E, 3A). The side chain hydroxyl groups of Thr374 and Thr386 make hydrogen bond contacts with the carboxyl group of leucine, whereas the free amine donates a hydrogen bond to the backbone carbonyl of Thr377 (Fig. 2A, 3A).

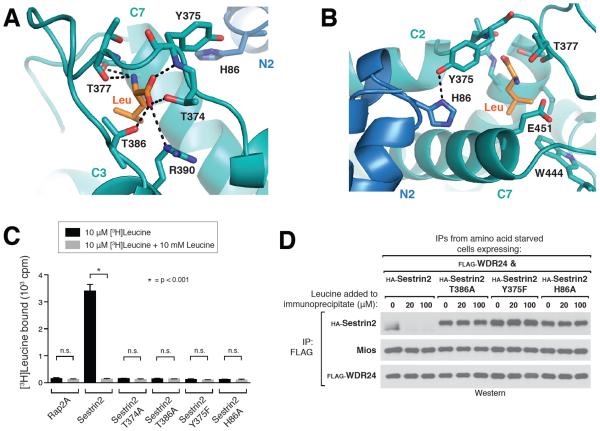

Figure 3. A lid-latch mechanism is required for leucine binding by Sestrin2.

A) Top-down view of the leucine bound pocket, focusing on the “lid” residues Thr374, Thr377, and Thr386 which form hydrogen bonds with the amine and carboxyl groups of leucine (indicated by black dashed lines). Leucine is represented as a stick model (orange). Helix numbers are labeled as in 1A.

B) Orthogonal view of the leucine binding pocket, focusing on the “latch” formed by the predicted hydrogen bond between Tyr375 and His86, which locks the lid in place over the bound leucine (orange). Helix numbers are labeled as in 1A.

C) Binding of Sestrin2 T374A, T386A, Y375F and H86A mutants of Sestrin2 to leucine. Binding assays were performed and immunoprecipitates analyzed as in Figure 2C.

D) Effect of leucine on the interactions of Sestrin2 T386A, Y375F or H86A with GATOR2 in vitro. FLAG immunoprecipitates were prepared from cells stably expressing FLAG-WDR24 and transiently expressing the indicated HA-tagged Sestrin2 constructs and analyzed as in 2D.

To analyze the importance of these lid interactions for leucine detection by Sestrin2, we generated mutants predicted to eliminate the critical contacts between the lid and leucine. Mutation of either Thr374 or Thr386 (T374A or T386A) abolished the interaction with leucine and resulted in a constitutive interaction with GATOR2, (Fig. 3, C and D), demonstrating a crucial role for the lid in leucine binding.

Although our in vitro binding data demonstrated a requirement for both the N- and C-terminal halves of Sestrin2 (Fig. 1D), the structural model shows that the bound leucine only makes direct contacts with residues in the C-terminal domain (Fig. 2A). Further structural analysis however revealed that the lid residue Tyr375 forms a tight hydrogen bond with the N-terminal residue His86, located in a loop between helices N2 and N3 adjacent to the leucine-binding pocket (Fig. 3B). This interaction appears to form a “latch,” which locks the lid in place over the bound leucine. Indeed, this inter-domain contact appears to be critical for the Sestrin2-leucine interaction, as specifically eliminating this hydrogen-bonded latch with either a Y375F or H86A mutation abolished leucine binding (Fig. 3, C and D). Both Tyr375 and His86 are also highly conserved in Sestrin proteins across organisms (Fig. 2E, S4). The requirement for His86 to maintain the latch interaction likely explains why the N-terminal domain of the protein is also essential for the interaction with leucine.

Altering the leucine sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway in cells

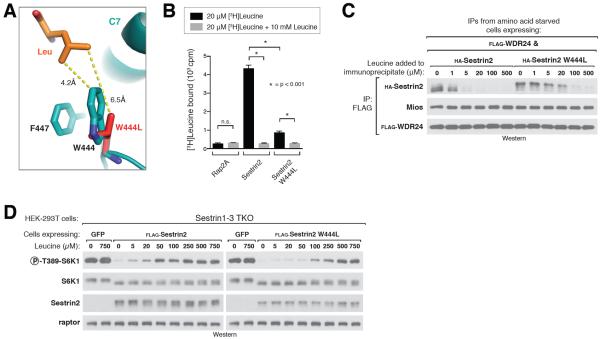

One prediction for a bona fide cellular leucine sensor is that its affinity for leucine should in part determine the sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway to leucine. We tested this hypothesis directly by generating a mutant of Sestrin2 with lower affinity for leucine. We predicted that deepening the hydrophobic base of the pocket by mutating Trp444 to Leu (W444L) would reduce the van der Waals contacts with the bound leucine side chain, thereby weakening but not eliminating the interaction (Fig. 4A). Indeed, the Sestrin2 W444L mutant bound one-sixth to one-eighth the amount of leucine that bound to wild-type Sestrin2 (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, addition of ~10 to 15 fold more leucine was required to fully dissociate the W444L mutant from GATOR2 compared to wild type Sestrin2 (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Altering the leucine sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway in cells.

A) Close-up view of Sestrin2-bound leucine (orange) and the pocket floor residues Phe447 and W444, with the W444L mutant (red) overlaid onto the wild-type protein (teal). Both residues are represented as stick models. Numbers indicate distance from leucine to residue 444 in Sestrin2 WT and Sestrin2 W444L.

B) Leucine binding by Sestrin2 W444L. Binding assays were performed and immunoprecipitates analyzed as in Figure 2C.

C) Higher concentrations of leucine are required to dissociate Sestrin2 W444L from GATOR2 compared to Sestrin2 WT. FLAG immunoprecipitates were prepared from cells stably expressing FLAG-WDR24 and transiently expressing the indicated HA-tagged Sestrin2 constructs and analyzed as in figure 2D.

D) Sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway to leucine in Sestrin1–3 triple-knock-out (TKO) cells expressing Sestrin2 wild type or W444L. HEK-293T cells generated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system expressing the indicated proteins via lentiviral transduction. Cells were starved of leucine for 50 minutes then re-stimulated with the indicated amount of leucine for 10 minutes. Cell lysates from one representative experiment were prepared and analyzed via immunoblotting.

To test the effect of this mutation on mTORC1 signaling in cells, we used a HEK-293T cell line in which Sestrin1, 2 and 3 were knocked-out the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Sestrin TKO cells). The mTORC1 signaling in these cells is fully resistant to leucine deprivation, and re-introduction of wild-type Sestrin2 restores normal signaling with half-maximal mTORC1 activity occurring upon addition of ~20 to 50 μM leucine (20, Fig. 4D). Expression of Sestrin2 W444L in the Sestrin TKO lines however shifted the dose response of mTORC1 to leucine, such that addition of ~250 to 500 μM was required to achieve half-maximal activation of the pathway (Fig. 4D). Thus, the affinity of Sestrin2 for leucine is a major determinant of the sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway to leucine in human cells.

Although the overall hydrophobicity of the pocket floor is well conserved, the specific residues present at the W444 and F447 positions vary across organisms, and some organisms, including Drosophila, carry the corresponding W444L mutation (Fig. 2E). These differences may alter the shape and depth of the leucine pocket, leading to different affinities or specificities for leucine in different organisms. This may represent an evolutionary adaptation to enable efficient sensing of leucine concentrations that are physiologically relevant in these organisms.

Characterizing the GATOR2 binding site on Sestrin2

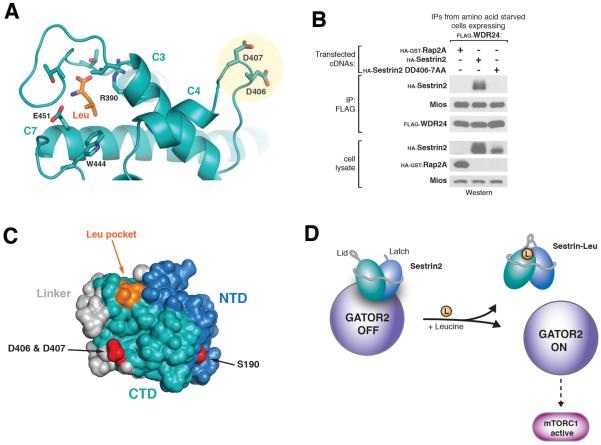

To better understand how leucine binding triggers dissociation of Sestrin2 from GATOR2, we sought to structurally characterize the GATOR2 binding interface of Sestrin2. Mutagenesis studies identified residue S190 in the NTD as required for GATOR2 binding (20), however this site is distal to the leucine-binding pocket. Mapping electrostatic potential onto the solvent-exposed surface of Sestrin2 revealed a region in close proximity to the leucine-binding site containing the highly conserved charged residues Asp406 and Asp407 (Fig. 5A, S5, A and B). Mutating these residues to alanine (DD406-7AA) completely eliminated GATOR2 binding without affecting leucine binding (Fig. 5B, S5C), suggesting that this region is required for the Sestrin2-GATOR2 interaction. Thus, Sestrin2 may make multiple contacts with GATOR2 through both the NTD and CTD (Fig. 5C, 1B), consistent with both halves of Sestrin2 being required for GATOR2 binding (Fig. 1D).

Figure 5. Identification of GATOR2 binding site and model of leucine sensing by Sestrin2.

A) View highlighting the conserved surface aspartates Asp406/407 and their position relative to the bound leucine (orange).

B) Co-immunoprecipitation of GATOR2 with Sestrin2 wild type or DD406-7AA. FLAG immunoprecipitates were prepared from cells stably expressing FLAG-WDR24 and transiently expressing the indicated HA-tagged Sestrin2 constructs and analyzed as in 2D.

C) Surface view of Sestrin2 highlighting the GATOR2 binding sites (red) and their position relative to the leucine-binding pocket (orange). Domains are colored as in 1A.

D) Model of leucine sensing by Sestrin2. Binding of leucine (orange) causes closing of the lid-latch, resulting in a conformational change altering the position of the GATOR2 binding site in the CTD. This leads to dissociation of Sestrin2 from GATOR2, enabling GATOR2 to activate the mTORC1 pathway.

Conclusions

Our results provide a structural model of leucine sensing by the Sestrin2-mTORC1 pathway and shed light into the mechanism through which mTORC1 couples cell growth to leucine availability. The structure shows that Sestrin2 contains an evolutionarily unique leucine-binding pocket consisting of a hydrophobic floor that determines specificity for the side-chain of leucine, with adjacent glutamate and arginine residues that coordinate the free amine and carboxyl groups, respectively. An additional “lid-latch” mechanism helps lock the ligand in place and is required for binding.

Our structure also reveals a highly conserved GATOR2 binding site in close proximity to the leucine pocket, suggesting possible mechanisms for how leucine binding can cause dissociation of Sestrin2 from GATOR2. The key residues for the GATOR2 interaction, Asp406 and Asp407, are located on a loop separated from the “lid” of the pocket by the 15-residue helix C3 (Fig. 5A). It is therefore conceivable that a conformational change in the lid, corresponding to leucine binding or release, could transmit a conformational change to the GATOR2 binding site via movement of helix C3 (Fig 5D). Alternatively, a segment of the partially disordered Linker domain, which contacts the leucine pocket via Leu261 in helix L1 (Fig. S3A), is also in close proximity to the GATOR2 binding site in our structure (Fig. 5C). Therefore, changes in the leucine binding state of Sestrin2 could potentially alter the position of the Linker, thereby affecting the availability of the GATOR2 binding site.

Despite these insights, several important questions remain. Fully understanding how leucine binding causes dissociation of Sestrin2 from GATOR2 will likely require the structure of either apo-Sestrin2 or the Sestrin2-GATOR2 complex. Furthermore, understanding the exact mechanism by which Sestrin2 inhibits the mTORC1 pathway awaits the elucidation of the molecular function of GATOR2.

Finally, as a critical regulator of cell growth, mTORC1 is mis-regulated in various human diseases including cancer, diabetes, and aging (1, 29). By revealing the mechanism through which a natural small molecule regulates this pathway, our results may enable the identification of compounds to pharmacologically target the nutrient-sensing pathway upstream of mTORC1 in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Sabatini and Schwartz labs for helpful insights. We also thank Cell Signalling Technologies (CST) for providing many antibodies. The X-ray crystallography was conducted at the Advanced Photon Source Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (APS NE-CAT) beamlines, which are supported by award GM103403 from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Use of the APS is supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Science under contract DEAC02-06CH11357. This work was supported in part by the NIH Pre-Doctoral Training Grant T32GM007287. This work has also been supported by grants from the US NIH (R01CA103866 and AI47389) the Department of Defense (W81XWH-07-0448) to D.M.S. Fellowship support was provided by the NIH to R.L.W. (T32 GM007753 and F30 CA189333), L.C. (F31 CA180271) T.W. (F31 CA189437). T.W. is also supported by an award from the MIT Whitaker Health Sciences Fund. M.E.P. is supported by the Sally Gordon Fellowship of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-112-12) and a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Postdoctoral Fellowship (BC120208). D.M.S is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:21. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dibble CC, Manning BD. Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nature Cell Biology. 2013;15:555–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2013;14:133. doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potier M, Darcel N, Tomé D. Protein, amino acids and the control of food intake. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2009;12:54–58. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831b9e01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greiwe JS, Kwon G, McDaniel ML, Semenkovich CF. Leucine and insulin activate p70 S6 kinase through different pathways in human skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2001;281:E466–471. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.3.E466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair KS, Schwartz RG, Welle S. Leucine as a regulator of whole body and skeletal muscle protein metabolism in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:E928–934. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.5.E928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox HL, Pham PT, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Lynch CJ. Amino acid effects on translational repressor 4E-BP1 are mediated primarily by L-leucine in isolated adipocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C1232–1238. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.5.C1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch CJ, Fox HL, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Regulation of amino acid-sensitive TOR signaling by leucine analogues in adipocytes. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2000;77:234–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000501)77:2<234::aid-jcb7>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. Nutrients and growth factors in mTORC1 activation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013;41:902–905. doi: 10.1042/BST20130063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buerger C, DeVries B, Stambolic V. Localization of Rheb to the endomembrane is critical for its signaling function. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;344:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito K, Araki Y, Kontani K, Nishina H, Katada T. Novel role of the small GTPase Rheb: its implication in endocytic pathway independent of the activation of mammalian target of rapamycin. Journal of biochemistry. 2005;137:423–430. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell. 2012;150:1196. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sancak Y, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sancak Y, et al. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duran RV, Hall MN. Regulation of TOR by small GTPases. EMBO reports. 2012;13:121. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoncu R, et al. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science. 2011;334:678. doi: 10.1126/science.1207056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, et al. Metabolism. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2015;347:188–194. doi: 10.1126/science.1257132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebsamen M, et al. SLC38A9 is a component of the lysosomal amino acid sensing machinery that controls mTORC1. Nature. 2015;519:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature14107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bar-Peled L, et al. A Tumor Suppressor Complex with GAP Activity for the Rag GTPases That Signal Amino Acid Sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2013;340:1100–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1232044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfson R, et al. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. 2015. in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chantranupong L, et al. The Sestrins Interact with GATOR2 to Negatively Regulate the Amino-Acid-Sensing Pathway Upstream of mTORC1. Cell Reports. 2014;9:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmigiani A, et al. Sestrins Inhibit mTORC1 Kinase Activation through the GATOR Complex. Cell Reports. 2014;9:1281–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niesen FH, et al. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nature Protocols. 2007;2(9):2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated Sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science. 2004;304:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibrat JF, et al. Surprising similiarities in structure comparison. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996 Jun;6(3):377–85. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woo HA, Bae SH, Park S, Rhee SG. Sestrin 2 is not a reductase for cysteine sulfinic acid of peroxiredoxins. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:739–745. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koshkin A, Nunn CM, Djordjevic S, Ortiz de Montellano PR. The mechanism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD as defined by mutagenesis, crystallography, and kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:29502–29508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng M, Yin N, Li MO. Sestrins Function as Guanine Nucleotide Dissociation Inhibitors for Rag GTPases to Control mTORC1 Signaling. Cell. 2014;159:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen KR, Leksa NC, Schwartz TU. Optimized E. coli expression strain LOBSTR eliminates common contaminants from His-tag purification. Proteins. 2013;81:1857–61. doi: 10.1002/prot.24364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brohawn SG, Leksa NC, Spear ED, Rajashankar KR, Schwartz TU. Structural evidence for common ancestry of the nuclear pore complex and vesicle coats. Science. 2008;322:1369–1373. doi: 10.1126/science.1165886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morin A, et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. eLife. 2013;2:e01456. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of Macromolecular Assemblies from Crystalline State. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Notredame, et al. T-Coffee: A novel method for multiple sequence alignments. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrodinger LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Version 1.3r1 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim D-H, et al. mTOR Interacts with Raptor to Form a Nutrient-Sensitive Complex that Signals to the Cell Growth Machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boussif O, et al. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:7297–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsun Z-Y, et al. The Folliculin Tumor Suppressor Is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases That Signal Amino Acid Levels to mTORC1. Molecular Cell. 2013;52:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.