Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess preferences between child behavioral problems and estimate their value on a quality-adjusted life year (QALYs) scale.

METHODS

Respondents, age 18 or older, drawn from a nationally representative panel between August 2012 and February 2013 completed a series of paired comparisons, each involving a choice between 2 different behavioral problems described using the Behavioral Problems Index (BPI), a 28-item instrument with 6 domains (Anxious/Depressed, Headstrong, Hyperactive, Immature Dependency, Anti-social, and Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal). Each behavioral problem lasted 1 or 2 years for an unnamed child, age 7 or 10 years, with no suggested relationship to the respondent. Generalized linear model analyses estimated the value of each problem on a QALY scale, considering its duration and child’s age.

RESULTS

Among 5207 eligible respondents, 4155 (80%) completed all questions. Across the 6 domains, problems relating to antisocial behavior were the least preferred, particularly the items related to cheating, lying, bullying, and cruelty to others.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings are the first to produce a preference-based summary measure of child behavioral problems on a QALY scale. The results may inform both clinical practice and resource allocation decisions by enhancing our understanding of difficult tradeoffs in how adults view child behavioral problems. Understanding US values also promotes national health surveillance by complementing conventional measures of surveillance, survival, and diagnoses.

Keywords: Behavioral Problems Index, Quality-Adjusted Life Years, QALY, discrete choice experiments, patient-reported outcomes

INTRODUCTION

A year of life with no health problems is one quality adjusted life year (QALY) and its value serves as a common preference-based metric in comparative effectiveness research (CER). Specifically, any episode with health problems may be summarized by its equivalence in reduced lifespan with no health problems (i.e., QALYs) using responses from a health valuation survey. For example, a participant might be asked, “Which do you prefer: a year in mild pain or a 6-month loss in lifespan with no health problems?” Responses to such questions quantify preferences between health outcomes without referencing other considerations (e.g., money). The purpose of this study is to assess preferences between child behavioral problems and estimate their value on a quality-adjusted life year (QALYs) scale.

Although multiple studies have assessed preferences between child health scenarios using responses from valuation surveys (1–5) their results are typically not linked to any child health instrument, and therefore cannot directly summarize child health as measured in CER data. Furthermore, child health valuation studies must include a description of lifespan or risk of death in their scenarios to estimate the value of problems on a QALY scale. For example, an Australian study incorporated health scenarios as described by the Child Health Utility 9D, but excluded a lifespan attribute (i.e., no QALYs).(6) To date, only 2 studies are based on a child health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instrument and estimate loss on a QALY scale. Both studies valued the Pediatric Asthma Health Outcome Measure (PAHOM) using a standard gamble task, with samples of adults from Seattle, Washington (N=94) and Birmingham, Alabama (N=261).(7, 8) Due to this paucity in the literature, CER studies using the Health Utilities Index (9) and the EQ-5D (4) have applied the same QALY weights to both child and adult outcomes, as if their experiences were interchangeable. However, we know from other literature (5) that adults often express preferences about health care differently for children than for adults, especially when resources are limited.

The persistent lack of data on preferences for child health outcomes must be addressed. A PubMed search for the terms “children health-related quality of life” identified 3343 articles with only 127 of them published prior to 2000. The passing of the 2010 US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the formation of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has strengthened the importance of HRQoL as a patient-centered outcome.(10, 11) Furthermore, our expanding technological capacity to systematically collect real-time data has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of health-related experiences among children for CER and public health surveillance. In summary, clinical guidelines, resource allocations, and policy decisions are informed by formally weighing evidence on child health outcomes; yet, only one pediatric instrument (i.e., PAHOM) has been directly summarized on a QALY scale. In this study, we take the perspective of US adults and assess preferences between child health behavioral problems as described by the Behavioral Problems Index (BPI).

Developed by James L. Peterson and Nicholas Zill (12) and based on earlier work by Thomas Achenbach,(13) the BPI is a seminal measure of child behavior reported by mothers using 28 3-level items along 6 domains: Anxious/Depressed, Headstrong, Hyperactive, Immature Dependency, Anti-social, and Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal.(14–16) This validated instrument has been used broadly in a multitude of surveys, including the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics,(17) Chicago School Readiness Project,(18) Child Health Supplements to the National Health Interview Survey,(19–22) and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth.(23–28) The BPI clearly covers important child HRQoL domains, but does not capture all domains of child health, or the impact of behavioral problems on the HRQoL of others (e.g., caregivers). It is also not a “generic” measure of broader aspects of HRQoL, such as the Health Utilities Index (9) or the EQ-5D.(4) By summarizing the BPI on a QALY scale, this study provides a new tool that enhances the potential contribution of existing datasets for CER.

METHODS

Participants

To inform medical decision making and health policy, CER requires measurement and valuation.(29) Measurement typically involves surveys of health outcomes completed by patients (e.g., children) or their proxies (e.g., parents, caregivers). Valuation requires surveys of preferences from the perspective of decision makers (e.g., general population). For this valuation study, we surveyed adults (instead of children), age 18 years or older, who resided in the US, because adults typically make health care decisions for children. Respondents were recruited from a pre-existing nationally representative panel of US adults. To promote concordance with the 2010 US Census, we used 18 demographic subgroups (all combinations of 2 genders, 3 age groups, 3 race/ethnicity groups). Once a minimum number of respondents for a subgroup were received, additional respondents belonging to that subgroup were not allowed (or paid) to complete the survey. The survey was administered online between August 7, 2012 and February 5, 2013. The protocol, including its sampling design and survey instrument, was adapted from the PROMIS-29 valuation study (1R01CA160104) (30) and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (USF IRB #8236).

Survey

After consenting, respondents completed a screener in which they reported their current US state of residence, ZIP code, birthdate, race, Hispanic ethnicity, educational attainment and household income (Table 1). After the screener, respondents proceeded to the survey, which was composed of health, paired comparison, and follow-up components. The health component included the PROMIS-29, a validated measure supported by a National Institutes of Health initiative, as a measure of adult HRQoL.(31) The follow-up component asked about the respondent’s experience with parenting and selected childhood health conditions and offered an opportunity to leave survey feedback.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics by completion and compared to 2010 United States Census*

| Dropout N=805 # (%) |

Terminated N=247 # (%) |

Completed N=4155 # (%) |

p-value | Completed N=4155 % |

US 2010 Census % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18 to 34 | 192 (13.67) | 77 (5.48) | 1136 (80.85) | 0.017 | 27.34 | 30.58 |

| 35 to 54 | 271 (14.74) | 87 (4.73) | 1481 (80.53) | 35.64 | 36.70 | |

| 55 and older | 342 (17.42) | 83 (4.23) | 1538 (78.35) | 37.02 | 32.72 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 397 (15.67) | 123 (4.86) | 2013 (79.47) | 0.843 | 48.45 | 48.53 |

| Female | 408 (15.26) | 124 (4.64) | 2142 (80.10) | 51.55 | 51.47 | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 651 (15.37) | 190 (4.49) | 3394 (80.14) | 0.337 | 81.68 | 74.66 |

| Black or African American | 105 (16.38) | 43 (6.71) | 493 (76.91) | 11.87 | 11.97 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 (17.86) | 0 (0.00) | 23 (82.14) | 0.55 | 0.87 | |

| Asian | 21 (14.69) | 8 (5.59) | 114 (79.72) | 2.74 | 4.87 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 10 (20.00) | 1 (2.00) | 39 (78.00) | 0.94 | 0.16 | |

| Some other race | - | - | - | - | 5.39 | |

| Two or more races | 13 (11.82) | 5 (4.55) | 92 (83.64) | 2.21 | 2.06 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 97 (15.80) | 33 (5.37) | 484 (78.83) | 0.699 | 11.65 | 14.22 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 708 (15.41) | 214 (4.66) | 3671 (79.93) | 88.35 | 85.78 | |

| Educational attainment among age 25 or older | ||||||

| Less than high school | 86 (17.17) | 31 (6.19) | 384 (76.65) | 0.001 | 9.24 | 14.42 |

| High school graduate | 211 (18.89) | 59 (5.28) | 847 (75.83) | 20.39 | 28.50 | |

| Some college, no degree | 147 (15.30) | 54 (5.62) | 760 (79.08) | 18.29 | 21.28 | |

| Associate's degree | 66 (13.41) | 14 (2.85) | 412 (83.74) | 9.92 | 7.61 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 216 (13.76) | 60 (3.82) | 1294 (82.42) | 31.14 | 17.74 | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 22 (12.87) | 6 (3.51) | 143 (83.63) | 3.44 | 10.44 | |

| Refused/Don't know | 4 (26.67) | 0 (0.00) | 11 (73.33) | 0.26 | - | |

| Household income | ||||||

| $14,999 or less | 77 (14.37) | 29 (5.41) | 430 (80.22) | 0.129 | 10.35 | 13.46 |

| $15,000 to $24,999 | 123 (16.40) | 36 (4.80) | 591 (78.80) | 14.22 | 11.49 | |

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 105 (15.49) | 37 (5.46) | 536 (79.06) | 12.90 | 10.76 | |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 146 (15.72) | 35 (3.77) | 748 (80.52) | 18.00 | 14.24 | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 92 (12.87) | 37 (5.17) | 586 (81.96) | 14.10 | 18.28 | |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 86 (18.30) | 11 (2.34) | 373 (79.36) | 8.98 | 11.81 | |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 49 (12.50) | 21 (5.36) | 322 (82.14) | 7.75 | 11.82 | |

| $150,000 or more | 44 (16.54) | 16 (6.02) | 206 (77.44) | 4.96 | 8.14 | |

| Refused/Don't know | 83 (17.62) | 25 (5.31) | 363 (77.07) | 8.74 | - | |

Age, sex, race, and ethnicity estimates for the US are based on 2010 Census Summary File 1. Educational attainment and household income are based on 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Unlike the US Census, the American Community Survey excluded adults not in the community (e.g., institutionalized) and describes income by the proportion of households, not of adults.

Dropout refers to a respondent who exited the study either voluntarily or due to a loss of internet connection. Terminated refers to a respondent who was removed from the survey due to technical requirements (e.g., JavaScript not enabled).

Paired Comparison Component

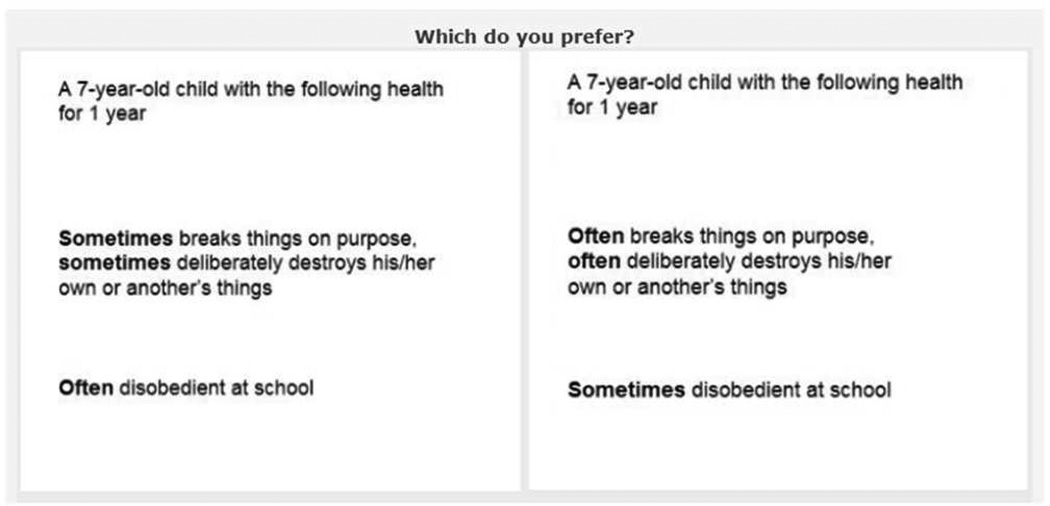

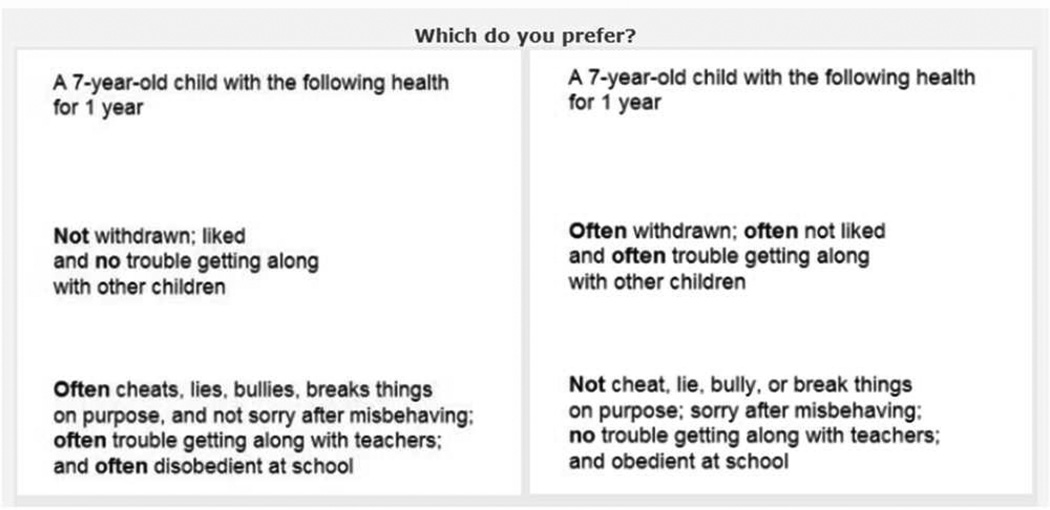

A paired comparison is a choice-based question that asks a respondent about his/her preference between 2 alternatives (e.g., Coke vs. Pepsi). Responses show how choices change with different combinations of alternatives. Each respondent first completed 3 example paired comparison questions: “Which do you prefer?” (Apple, Orange), (Good Health, Poor Health), or (Bad Health, Poor Health). The “Bad Health” vs. “Poor Health” question was included to prepare respondents for potentially more challenging descriptions later on the survey. Next, respondents were randomly assigned a base scenario (a scenario used as a reference point that does not change) and asked to complete a series of paired comparisons building from this base scenario. The base scenario described the age of an unnamed child (7 or 10 years old) and the duration of a behavioral problem (1 or 2 years). Aside from the 3 examples, the number of paired comparisons ranged from 33 to 40 pairs. Due to space considerations, the Appendix provides didactic description of the pairs, adjectival statements, paired selection, econometrics, and results, which are summarized in this section.

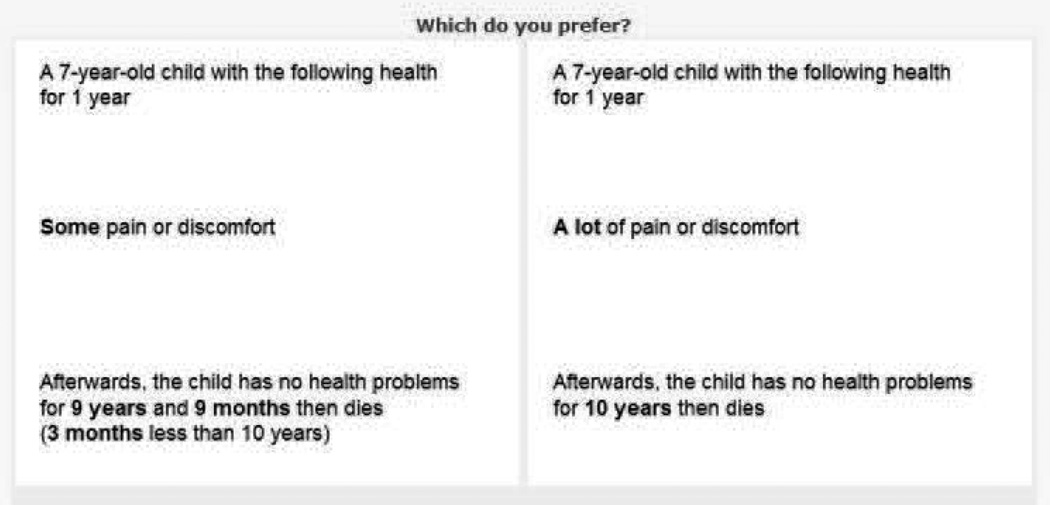

Initial pairs asked respondents to choose between a behavioral problem and a loss in lifespan given the assigned base scenario. For example, the paired comparison in Figure 1 has a base scenario for a 7-year-old child. In this task, the respondents must choose between a 5-year reduction in child lifespan (i.e., loss of 5 QALYs) and a behavioral problem, specifically, problems relating to Anxiety/Depression, Headstrong, and Immature Dependency for 1 year. For this 7-year-old child, the left alternative represents a 6-year lifespan with no problems, and the right is an 11-year lifespan that starts with 1 year of behavioral problems. For these initial pairs, the life span extended 10 years after the behavioral problem ended, which follows common practice in time trade-off (TTO) tasks and allows for sufficient range in loss of lifespan.(32) Remaining pairs asked respondents to choose between 2 behavioral problems. Respondents were assigned to see problems, described using statements derived from the BPI, for just one of two durations (1 year or 2 years). The use of 2 durations was included to assess the constant proportionality assumption. The episodic random utility model (ERUM) assigns value based on episode attributes, including duration (relaxing the constant proportionality assumption), while a health state approach (a.k.a., instant random utility model; IRUM) assumes constant proportionality (i.e., 2 years of problems has twice the value of 1 year). (33– 35) All pair sequences were randomly ordered to reduce sequence effects. Pairs were assigned to respondents according to 18 demographic subgroups to strengthen concordance with the 2010 US Census at the pair-level.

Figure 1.

Statistical Analysis

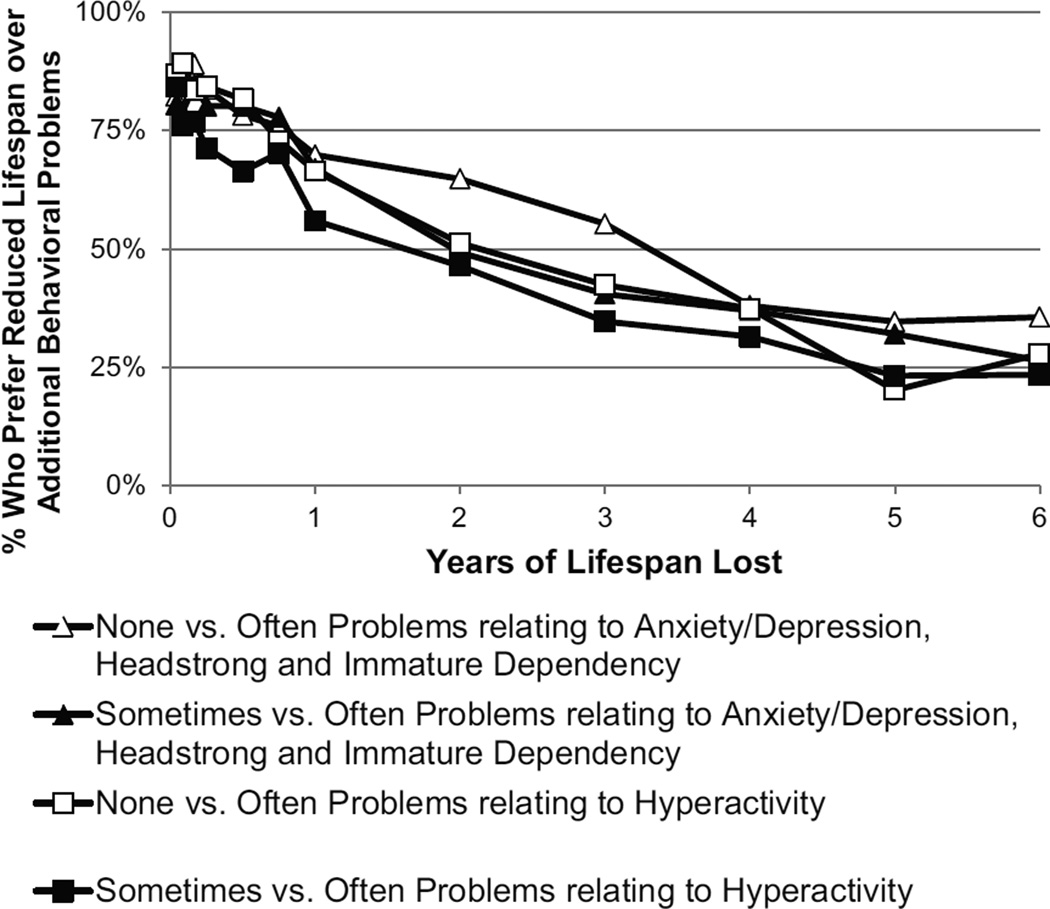

Screener responses of those who dropped out, were terminated, and completed the survey were compared using chi-squared tests and shown alongside the US 2010 Census results (Table 1). Responses to the 211 pairs were stratified by 4 base scenarios (i.e., each respondent sees only 1 of the 4 base scenarios). These pairs (shown in the Appendix) include 136 item pairs asking preference between item-specific attributes within each domain, 12 domain pairs asking about preference between domain-specific attributes, 15 class pairs asking about preference between groups of domains and 48 pairs asking about preference between behavioral problems and losses in lifespan (Figure 1). Figure 2 illustrates responses to 48 pairs comparing behavioral problem and losses in lifespan; however, all pair results are included in the Appendix.

Figure 2.

The BPI has 28 3-level items and captures up to 56 problems (i.e., differences in ordinal scale; see Tables 2 and 3). For each of the 844 pairs (4 base scenarios×211 pairs; see Appendix), the sample probability of choosing A over B, pk, was approximately normally distributed by the central limit theorem and served as the dependent variable of a generalized linear model. Each alternative (A and B) was represented by a linear regression, dh, that includes 56 coefficients, one for each indicator variable of a difference in ordinal scale. For example, the first item in the Anxiety/Depression (AD) domain is “sudden change in mood or feeling” and the value of the step from “no” to “sometimes” is represented by AD1,1 such that the first subscript represents the item and the second subscript represents the lower level of the difference in ordinal scale. The coefficients of the generalized linear model (GLM) were estimated by minimizing the weighted sum of squared error, , Σ 844/k=1 (P (Ak > Bk) − pk)2 / σ2k where P(Ak>Bk)=dB/(dA+dB) and σ2k = pk × (1-pk)/nk.(36, 37) To understand the motivation for the GLM approach, it is important to recognize that given a pair sample size, Nk, and a population probability, Pk, its sample probability, pk, is approximately normally distributed if Nk × Pk > 5 or Nk × (1•Pk) > 5. In this study, each pair had 50 or more responses; therefore, each of the 844 sample probabilities are approximately normally distributed assuming that their Pk are between 0.1 and 0.9. In the GLM, P(Ak>Bk) is a link function that best fits these normally distributed data. Furthermore, the model was re-estimated after stratifying the pairs by base scenario. Significance level was set at 0.05, and 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals were computed for all parameters.

Table 2.

The Value of Anxiety/Depression, Headstrong, and Hyperactive Problems

| Child Behavioral Problem by Domain and Item | None vs. Sometimes QALY (CI) |

Sometimes vs. Often QALY (CI) |

None vs. Often QALY |

Domain QALY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety/Depression | ||||

| Sudden changes in mood or feeling | 0.034 (0.025 – 0.041) |

0.075 (0.060 – 0.090) |

0.109 | |

| Feels or complains that no one loves him/her | 0.04 (0.03 – 0.049) |

0.103 (0.085 – 0.128) |

0.143 | |

| Too fearful or anxious | 0.031 (0.023 – 0.037) |

0.082 (0.067 – 0.099) |

0.113 | |

| Feels worthless or inferior | 0.084 (0.069 – 0.104) |

0.254 (0.231 – 0.320) |

0.338 | |

| Unhappy, sad, or depressed | 0.051 (0.039 – 0.062) |

0.239 (0.216 – 0.325) |

0.290 | 0.993 |

| Headstrong | ||||

| Rather high strung, tense and nervous | 0.046 (0.037 – 0.053) |

0.096 (0.081 – 0.118) |

0.142 | |

| Argues too much | 0.02 (0.014 – 0.023) |

0.061 (0.051 – 0.071) |

0.081 | |

| Disobedient at home | 0.025 (0.018 – 0.029) |

0.183 (0.161 – 0.23) |

0.208 | |

| Stubborn, sullen and irritable | 0.031 (0.024 – 0.036) |

0.090 (0.074 – 0.107) |

0.121 | |

| A very strong temper and sometimes loses it easily | 0.102 (0.085 – 0.129) |

0.230 (0.208 – 0.295) |

0.332 | 0.884 |

| Hyperactive | ||||

| Difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | 0.064 (0.050 – 0.075) |

0.128 (0.111 – 0.144) |

0.192 | |

| Easily confused or sometimes seems to be in a fog | 0.146 (0.123 – 0.168) |

0.243 (0.215 – 0.287) |

0.389 | |

| Impulsive or sometimes acts without thinking | 0.067 (0.053 – 0.077) |

0.211 (0.187 – 0.242) |

0.278 | |

| A lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts |

0.122 (0.104 – 0.139) |

0.196 (0.171 – 0.23) |

0.318 | |

| Restless, sometimes overly active and sometimes cannot sit still |

0.069 (0.056 – 0.079) |

0.154 (0.134 – 0.176) |

0.223 | 1.400 |

QALY: quality-adjusted life year; CI: confidence interval

Table 3.

The Value of Immature Dependency, Anti-social, and Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal Problems

| Child Behavioral Problem by Domain and Item | None vs. Sometimes QALY (CI) |

Sometimes vs. Often QALY (CI) |

None vs. Often QALY |

Domain QALY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immature Dependency | ||||

| Clings to adults | 0.014 (0.009 – 0.016) |

0.051 (0.040 – 0.059) |

0.065 | |

| Cries too much | 0.040 (0.031 – 0.047) |

0.096 (0.077 – 0.119) |

0.136 | |

| Demands a lot of attention | 0.021 (0.016 – 0.025) |

0.067 (0.055 – 0.079) |

0.088 | |

| Too dependent on others | 0.034 (0.026 – 0.040) |

0.083 (0.066 – 0.102) |

0.117 | 0.406 |

| Anti-social | ||||

| Cheats or sometimes tells lies | 0.448 (0.390 – 0.659) |

1.026 (0.943 – 1.697) |

1.474 | |

| Bullies, cruel and mean to others | 1.191 (1.122 – 1.881) |

1.628 (1.555 – 2.917) |

2.819 | |

| Not sorry after misbehaving | 0.267 (0.214 – 0.375) |

0.314 (0.273 – 0.447) |

0.581 | |

| Breaks things on purpose, sometimes deliberately destroys things |

0.470 (0.406 – 0.699) |

0.550 (0.474 – 0.879) |

1.020 | |

| Disobedient at school | 0.123 (0.093 – 0.171) |

0.411 (0.351 – 0.623) |

0.534 | |

| Trouble getting along with teachers | 0.142 (0.110 – 0.197) |

0.260 (0.211 – 0.393) |

0.402 | 6.830 |

| Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal | ||||

| Trouble getting along with other children | 0.301 (0.205 – 0.463) |

0.438 (0.331 – 0.770) |

0.739 | |

| Not liked by other children | 0.246 (0.164 – 0.376) |

0.469 (0.352 – 0.816) |

0.715 | |

| Withdrawn and sometimes does not get involved with others |

0.299 (0.201 – 0.452) |

0.307 (0.229 – 0.541) |

0.606 | 2.060 |

QALY: quality-adjusted life year; CI: confidence interval

RESULTS

Survey Participation

Of the 11496 respondents recruited for this study, 1075 (9.35%) visited only the consent page, 190 (1.65%) reported non-consent, and 408 (3.55%) dropped out during the screener. Among the 9823 respondents who completed the screener, 2669 (27.17%) belonged to a subgroup that already had sufficient respondents, and 1947 (19.82%) failed the screener requirements. Among the 5207 respondents who were allowed to enter the survey, 805 (15.46%) dropped out during the survey, and 247 (4.74%) were terminated due to technical requirements (e.g., JavaScript not enabled). The 4155 respondents who completed the survey were younger than those who dropped out, older than those who were terminated, and better educated than those who did not complete the survey (see Table 1). Compared to the 2010 US Census, the analytical sample was demographically similar yet better educated, with small differences at the extremes in annual household incomes (less than $15,000 and greater than $150,000). The sample sizes of the 844 paired comparisons pertaining to the BPI ranged from 51 to 80 respondents. The median survey duration was 25.21 minutes (interquartile range 19.5–34.2 minutes). Most participants who completed the survey reported that the survey was easy to understand (71%) and navigate (87%).

Choices

Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of respondents who preferred reduced lifespan over additional behavioral problems, combining responses across the 4 base scenarios. The value of each behavioral problem on a QALY scale is defined by where its line crosses 50% on the y-axis, because this is the point where exactly half of respondents prefer reduced lifespan over the behavioral problem. As expected, the percentages form lines that are largely parallel and decreasing. The height of a line implies greater willingness to sacrifice lifespan (i.e., in place of a less desirable problem). The topmost line (in this case, denoted with white triangles), indicates the least desirable problems compared to the lines below it. The third line (white squares) is higher (less desirable) than the fourth line (black squares) by construction, because it represents a difference between “none” to “often” compared to the difference between “sometimes” and “often” in the Hyperactivity domain. Interestingly, problems relating to Anxiety/Depression, Headstrong, and Immature Dependency (triangle lines) were less desirable than problems relating to Hyperactivity (square lines).

Value of Child Behavioral Problems

Tables 2 and 3 describe the value of child behavioral problems on a QALY scale assuming that each problem lasts for 1 year. For all items, the difference between level 1 (never) and 2 (sometimes) was less than the difference between level 2 (sometimes) and 3 (often). The value of an item is the sum of its differences in levels, and the value of a domain is the sum of its item values. For example, consider the first item within Hyperactivity: “difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long.” The value of having this problem “sometimes” for 1 year equals a loss of 0.064 QALYs, and the value of the difference between having the problem “sometimes” versus “often” equals a loss of 0.128 QALYs; therefore, the value of the item is 0.192 (i.e., 0.064+0.128). The value of the domain Hyperactivity is 1.400 QALYS (i.e., 0.192+0.389+0.278+0.318+0.223), which includes the values of its 5 items.

Across the 6 domains, problems relating to Anti-social behavior were by far the least desirable, particularly the items relating to cheating, lying, bullying, and cruelty to others. This domain was less desirable than all other domains combined (6.630 vs. 5.743 QALYs), possibly because it imposes a burden on others by definition. The least undesirable domain was Immature Dependency (0.406 QALYs), which had the least undesirable item, “sometimes clings to adults” (0.014 QALYs).

Differences by Age and Problem Duration

After stratifying the estimation by base scenario (see Appendix), we found that only 2 of the 56 problems had significant differences in value by child age at the 1-year and 2-year durations. Both differences relate to the Hyperactivity item, “restless, overly active and cannot sit still.” The first shows a higher value (i.e., less preferable) on “sometimes” hyperactive at age 10 compared to age 7 years (0.057 difference in QALYs; 95% CI 0.014–0.101). The second places a lower value (i.e., more preferable) on “often” hyperactive at age 10 compared to age 7 (0.044 difference in QALYs; 95% CI 0.001–0.096). Additionally, we found many significant differences by problem duration at both age 7 and 10 years (29 and 12 out of 56, respectively). The signs and magnitude of the duration effects suggest that doubling the duration of behavioral problems less than doubles its value.

DISCUSSION

Given the wealth of available data using the BPI, the importance of CER for medical decision making and health policy, and our expanding technological capacity to systematically collect health data, these results have the potential to greatly improve our understanding of child behavioral problems from the perspective of US adults.

This study found that half of US adults would prefer a 7-year reduction in a child’s dozen-year lifespan than for there to be 1 year of that child’s anti-social behavior (i.e., often cheats, lies, bullies, breaks things on purpose, and not sorry after misbehaving; often trouble getting along with teachers; and sometimes disobedient at school). This finding may reflect the readily observable impact of antisocial behavior on the child as well as the impacts experienced by his/her family, school, and community. This 7-to-1 ratio is clearly quite large, but emphasizes the importance of access to child mental health services and funding of pediatric surveillance and research. Keeping in mind that the losses in lifespan occur in early adulthood and the suffering occurs while a child, the prevention of bullying among children may be worth the seemingly high loss in adult lifespan from the perspective of US adults, possibly due to the perceived long term and communal consequences of anti-social behavior or the fact that adults have had their “fair innings” (i.e., everyone is entitled to some “normal” span of health, anyone failing to achieve this has been cheated, and anyone getting more than this is “living on borrowed time”). (32, 38, 39

On the methodological side, our study explores 2 key assumptions underlying QALYs: age independence and constant proportionality in time.(33) The former implies that adults’ preferences regarding child behavioral problems do not depend on the age of the child experiencing it, and the latter states that the value of a problem is in a constant proportion to its duration. For the first to hold true, the preferences concerning losses experienced by a 7-year old would be the same as those experienced by a 10-year old. For the second, our estimate of the loss in QALYs caused by a problem lasting 2 years should be twice as large as the loss due to the same problem lasting 1 year. This assumption is rarely tested among adults, although it is known to be violated in previous studies.(40) For children, we hypothesized that both assumptions may be violated because health norms vary greatly between younger and older children (e.g., self-care). Future studies should further investigate these issues and how they may differ between child and adult populations.

Our findings show violations of both assumptions; however, the differences between ages 7 and 10 seem minor compared to the significant violation of constant proportionality: the loss in QALYs for having 2 years of behavioral problems was considerably less than twice the loss for having 1 year of problems. This violation of constant proportionality may be due to faith in the resilience of children, their families, schools, communities, and a child’s ability to adapt to behavioral problems with time. This study, like most valuation studies, asked the respondent to assume that children can be completely rehabilitated after a 1- or 2-year period; however the respondent’s failure to do so (i.e., once a bad egg, always a bad egg) may lead to over-estimation in the first year. We recommend further research in this area. It should be noted that constant proportionality is an assumption of the QALY metric, not of the methods in this analysis. To date, no study has assessed the value of child behavioral problems on a QALY scale. In the tradition of adult health valuation, paired comparisons have been employed for the valuation of SF-36, PROMIS-29, and EQ-5D instruments.(41–43) Pairs including a 10-year lifespan are used frequently in the TTO task, common in adult health valuation, which employs an adaptive series of paired comparisons.(15, 16, 44, 45) Unlike TTO-based studies, this preference study is based solely on non-adaptive paired comparisons. Simplifying the comparisons and task reduces cognitive burden, expedites response, and reduces the use of some simplifying heuristics which may introduce bias in complex choices.(46) Future research will show whether the results of this approach might replace the traditional adaptive tasks (e.g., standard gamble).

The study design also raises questions about effects of using unnamed children and 10-year time horizons in the valuation of child health. Usually adult participants are asked to value their own health, not the health of an unnamed child. The results might differ with a familial or named description of the child (e.g. by gender, socio-economic status, or disease), particularly among parents or survivors of childhood diseases. Also, the preferences may change if the reductions in lifespan occurred later in the child’s life (as an older adult), instead of 10 years later when the child becomes a young adult. Although 10 years is the most common time horizon, a wide range of lifespans have been incorporated in TTO studies.(47) The use of the 10-year time horizon may be particularly problematic when applied to the valuation of child health. For example, the child in Figure 1 has a tragically short lifespan regardless of the choice (13 and 18 years, respectively), which may confound the preference elicitation task. However, a longer horizon would likely increase willingness to reduce adult lifespan (i.e., intertemporal discounting) to prevent child behavioral problems, further inflating the seemingly high estimates (i.e., 7-to-1 ratio). The issues of unnamed children, “fair innings”, and the 10-year time horizon have been raised in other health valuation literature, but represent an unresolved area for which there is no standard.(32, 38) The present paper adds to the sparse literature on adult valuations of child health outcomes, but its novelty also suggests that the results be approached with caution. Over time, as this literature grows, these issues and how they impact valuation may be tested further.

A typical use of study findings like ours would be to facilitate health technology assessment (HTA) or health economic evaluation of the costs and benefits of alternative medical interventions and technologies. This study, like most valuation studies, used an additive regression model on a QALY scale where “often” problems is the sum of the difference between “none” and “sometimes” and the difference between “sometimes” and “often.” Although HTA and economic evaluation remain controversial, especially in the US,(48) they provide an important framework for medical decision making at both the clinical and managerial levels.(5, 49–51) For child health, one major shortcoming of HTA to date has been the lack of QALY weights for HRQoL instruments that are specific to children.(52) Adult HRQoL instruments often focus on aspects of health that are more relevant to the elderly and miss many important characteristics for children. Moreover, it is inappropriate to assume that how adults experience HRQoL is the same as how children experience HRQoL.(9) Future studies may apply our results to existing datasets or examine the preferences of adult subsamples (e.g., parents, caregivers) and children themselves.

Our study helps to improve quantitative and economic evaluation in medical decision making and HTA by providing a preference-based measure of child behavioral problems. Given the growing emphasis on patient-centered outcomes,(53) this advancement is relevant. Our results also show that future HTA for child health policy will need to consider methodological improvements because we found violations of both the constant proportionality in duration and age independence assumptions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff in Dr. Craig’s lab at Moffitt Cancer Center for their contributions to the research and creation of this paper: Michelle Owens, MA (psychology; research coordinating), Catherine Blackburn, BS (literature review), and Carol Templeton, BA (technical writing; copyediting).

Financial support for this research was provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA160104) and Dr. Craig’s support account at Moffitt Cancer Center. The funding agreements ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Appendix

This appendix provides a didactic overview of the study methods used in the Child Health Valuation Study (CHV). The purpose is to compensate for the brevity necessary in publication and to aid readers who are less acquainted with the use of paired comparisons in health preference research. There are four sections. The first section decomposes a paired comparison into its components and reviews vocabulary that might aid the reader’s understanding of the preference elicitation task. The second section presents the attributes used in the task and their relationship to parameters. The third section describes the selection of pairs and shows the results at the pair level. The fourth section introduces econometric concepts and the value estimation.

Section 1: Paired comparison

In CHV, respondents completed a series of paired comparisons that traded off health and length of life (lifespan pairs) followed by a second series of pairs that traded off health (health pairs). Prior to starting the lifespan pairs, respondents completed three example pairs (apple vs. orange; good health vs. poor health; bad health vs. poor health). Afterwards, they were informed that they would “read a series of paired comparisons that describe child health and length of life.” They were then told to “imagine that the child’s health is the same except for the problems described and that the child could be any child in the United States” and that “you must choose between child health and length of life from your current adult perspective.” A detailed report of the methods used in CHV and screenshots of the paired comparisons are available online: http://labpages.moffitt.org/craigb/.

Figure 1 provides an example of a paired comparison task with a lifespan pair. Each paired comparison was presented in a page-by-page format. To complete a paired comparison task, the respondent was forced to choose by clicking on the alternative (i.e., box) that he or she preferred. Such a task is choice based (i.e., no scales) and does not impose set effects (i.e., only two alternatives); however, there may be some influence from stimuli seen earlier.

Figure 1 Example of a paired comparison using a lifespan pair.

-

❶

The respondent is asked, “Which do you prefer?” because the purpose of this task is to measure preference. Other paired comparisons may be designed to ask about judgment (e.g., “Which is better?” vs. “Which is healthier?”).

-

❷

Under the question, the two alternative options to the paired comparison are shown in boxes side by side. Each box contains a written description. This description is called a partial profile because it describes only a portion of a person’s health. It is not possible to fully characterize health in the brevity of text allowed by the box (i.e., full profile).

-

❸

The text at the top of each box describes the attributes common to both alternatives, known as the base scenario or pivot. To compare two alternatives, each must affect the same person with the same start and end time. For example, if one alternative describes 1 year for a 7-year-old child, the other alternative must describe 1 year for a 7-year-old child. In the lifespan pairs, the respondent was told that the description represents a child’s health with a shared starting age and ended in death.

-

❹

Underneath the pivot description, the first attribute is described for each alternative. In this example, the first attribute is emotional health, specifically, Anxiety/Depression, Headstrong, and Immature Dependency. The description of this attribute is “better” on the left than on the right. Attribute descriptions are called adjectival statements because they are constructed to link directly to health outcomes data measured using adjectival scales.

-

❺

Underneath the first attribute, the second attribute is described for each alternative. In this case, the attribute is years with no health problems (e.g., “Afterwards, the child has no health problems…”). The description of this attribute is “better” on the right than the left, which may compensate for the health problem described in the first attribute. A pair with only two attributes reflects a tradeoff (i.e., opportunity cost) and is known as a bipedal pair.

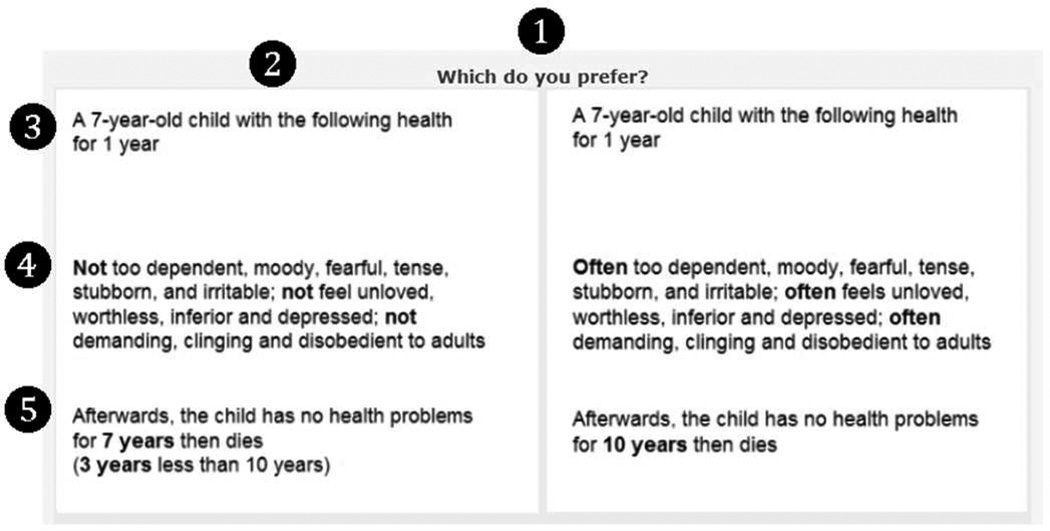

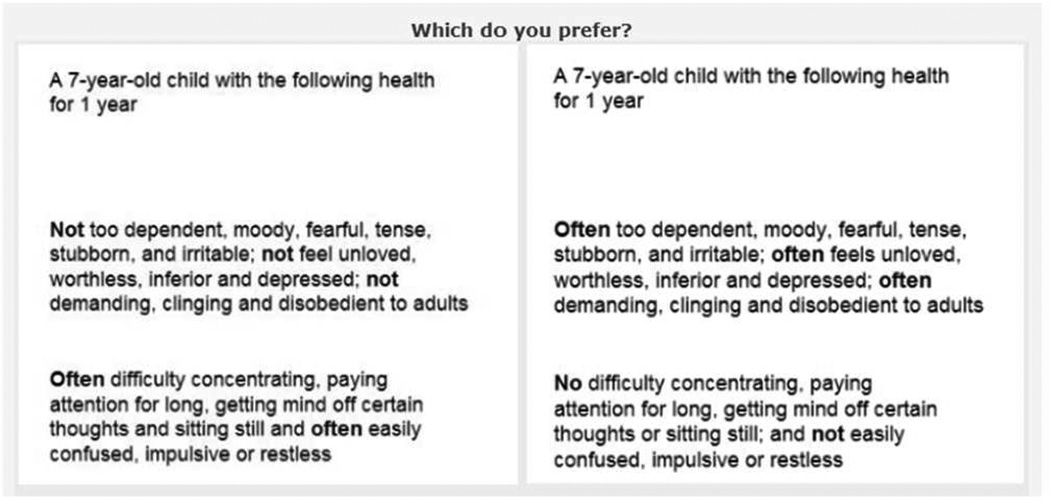

Figure 2 provides an example of a paired comparison task using a bipedal health pair. The only difference from a bipedal lifespan pair is that the second attribute is a second health problem, communication and learning problems, instead of “years with no health problems.” By changing the second attribute, with the description of the better level of the second attribute on the opposite side from the better level of the first attribute, preferences between pain/discomfort and self-care can be measured.

Figure 2 Example of a paired comparison with a health pair.

Each respondent completed a series of preference elicitation tasks. Each task had a bipedal pair of pivoted partial profiles based on adjectival statements from the Behavioral Problems Index (BPI). Paired comparison responses had no effect on the selection and presentation of subsequent pairs (i.e., non-adaptive). For all pairs, attributes were randomized up and down as well as left and right; however about half of the respondents saw the first attribute get worse from left to right on all pairs, and the other half saw the first attribute get better from left to right on all pairs. This consistency in format simplified the sequence of tasks.

At first glance, such paired comparisons appear different from the time trade-off (TTO) task commonly used to value health outcomes based the EQ-5D (e.g., 1993 UK MVH). However, a TTO is an adaptive series of paired comparisons using bipedal pairs of pivoted partial profiles based on adjectival statements. In both the TTO and this study, the health descriptions are taken from a health instrument. The primary difference is that a TTO adapts to select the next lifespan pair using a fixed algorithm based on previous responses and concludes when a respondent states that the two alternatives are equivalent (i.e., statement of indifference). This adaptation process and judgment-based termination gives the appearance of more precise preference measurement at the respondent level, but produces an array of biases in the response distribution (e.g., ceiling and floor effects; sawtooth distributions; sequence effect). Although paired comparisons have much room for improvement and innovation, the removal of adaptation has successfully mitigated some biases commonplace with conventional preference elicitation tasks (e.g., standard gamble). In summary, the task used in this study is nested within the TTO, but non-adaptive paired comparisons have fewer assumptions and biases.

Section 2: Attributes and Their Relationship to Parameters in the Analysis

The first step in the design of any health preference study is to determine what attributes to value. This section lists the attributes as they pertain to the BPI and the parameters that represent their values. The pivot, or text at the top of each box (#3 in Table 1), describes the attributes common to both alternatives, namely the age of the child (7 or 10 years old: Age7 and Age10) and the durations of loss in child health-related quality of life (HRQoL; 1 year or 2 years: Dur1 and Dur2).

The first attribute in any paired comparison describes a difference in child HRQoL across six domains: Anxiety/Depression (AD), Headstrong (HS), Immature Dependency (ID), Hyperactive (HY), Antisocial (AS), and Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal (PS). Each of the 28 items in the BPI has 3 levels. Table 2 shows each item and level. By definition, each difference in level has a non-negative value. Overall, the instrument has 56 one-step differences (e.g., 1 to 2) and their values are represented by a single 2-letter parameter in upper case (e.g., ADj,k) with an index, j, for the item number within the domain and an index, k, for the lower level of the difference. For example, the third item in the Anxiety/Depression domain is “fearful or anxious” and the value of the step from “sometimes” to “often” is represented by AD3,2 (i.e., first subscript represents the item and the second subscript represents the lower level of the one-level step). Table 2 also shows the value of two-step differences (i.e., 1 to 3), represented by the sum of two 1-step parameters (e.g., AD1,1+AD1,2= AD1,k). Aside from the child HRQoL attributes, we included 15 losses in lifespan (Table 3), which is represented using days (Dk), months (Mk), and years (Yk), where the index represents the number of time units. For example, in Figure 1, respondents chose between a 7-year-old child (Age7) experiencing a lot of emotional problems for 1 year (Dur1×[ADj,k+HSj,k+IDj,k]) and losing 3 years of life (Y3). Figure 2 is a health pair that is similar to Figure 1, except that the second attribute is communication and learning problems for 1 year, not time (Dur1×HYj,k). Tables 2 and 3 show all of the adjectival statements and how they correspond to the values (i.e., parameters to be estimated).

Section 3: Pair Selection

In addition to lifespan pairs, three groups of health pairs were selected for CHV. For each group, this section provides an example, describes the selection of pairs, and shows the results of all pairs within the group. The first group involved tradeoffs between items within domain, the second group involved tradeoffs between domains within class, and the third group involved tradeoffs between classes. This section concludes with a description of lifespan pair selection.

In this section, pairs are described by their parameters (Section 2) using a shorthand for levels of each attribute in a pair: ([A1,A2],[B1,B2]). For example, in Figure 2, the tradeoff is frequent emotional problems, ADj,k+HSj,k+IDj,k versus frequent communication and learning problems, HYj,k, so that the pair is ([1,3],[3,1]). Sample size ranged from 51 to 80.

Item Pairs

Tables 4 to 10 show the item pairs, including the proportion of respondents who prefer Alternative B (alternative on the right) over Alternative A (alternative of the left). Item pairs compare the effects of items within the same class. For example, Figure 3 is a tradeoff between often breaking things and deliberately destroying his/her own or another’s things (AS4,2) and often disobedient at school (AS5,2). The BPI has 28 three-level items and captures 56 problems (i.e., difference in scale; see Table 2). Specifically, every item within a domain was compared to every other item in the same domain for the same unit change in level: ([1,2],[2,1]) and ([2,3],[3,2]) (Tables 4 to 9). However, we also included a series of item pairs that compared the first change to a second change: ([2,2],[3,1]) (Table 10). Aside from these pairs, six pairs relating to PS were run twice and are noted as “(1 of 2)” and “(2 of 2).”

Figure 3 Example of an item paired comparison.

Domain Pairs

In addition to comparing all items within the BPI, we selected domain pairs to allow for the identification of independent effects of domains within a class. We grouped the items into six domains: AD, HS, ID, HY, AS, PS. All domains within a class were compared to each other; HY was in its own class, so was not included in the domain pairs. Specifically, we compared ID vs. UA; ID vs. HS; HS vs. AD; and PS vs. AS at both one-step and two-step changes: ([1,2],[2,1]), ([2,3],[3,2]), ([1,3],[3,1]), resulting in three pairs for each domain comparison (Table 11). For example, Figure 4 is a tradeoff ([1,3],[3,1]) between PSj,k and ASj,k.

Figure 4 Example of domain paired comparison.

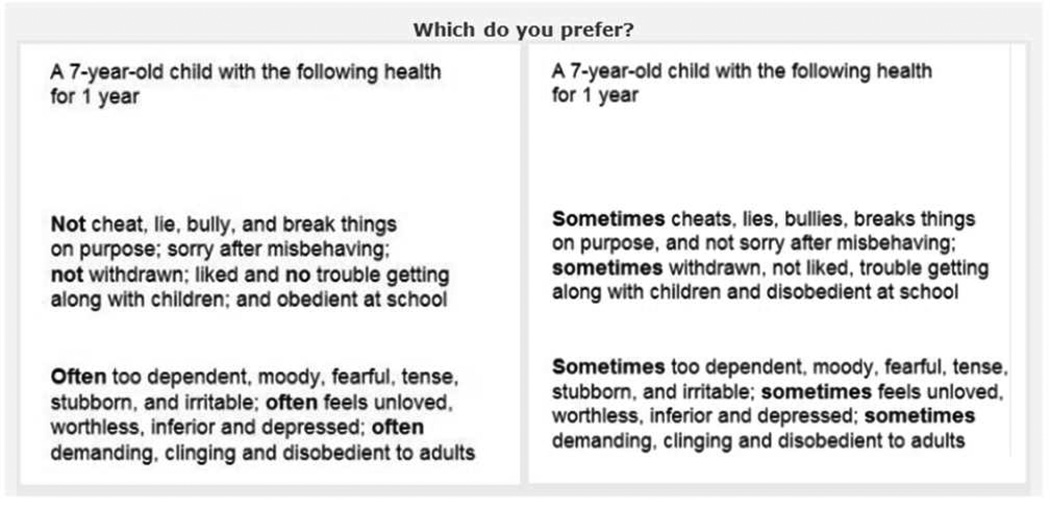

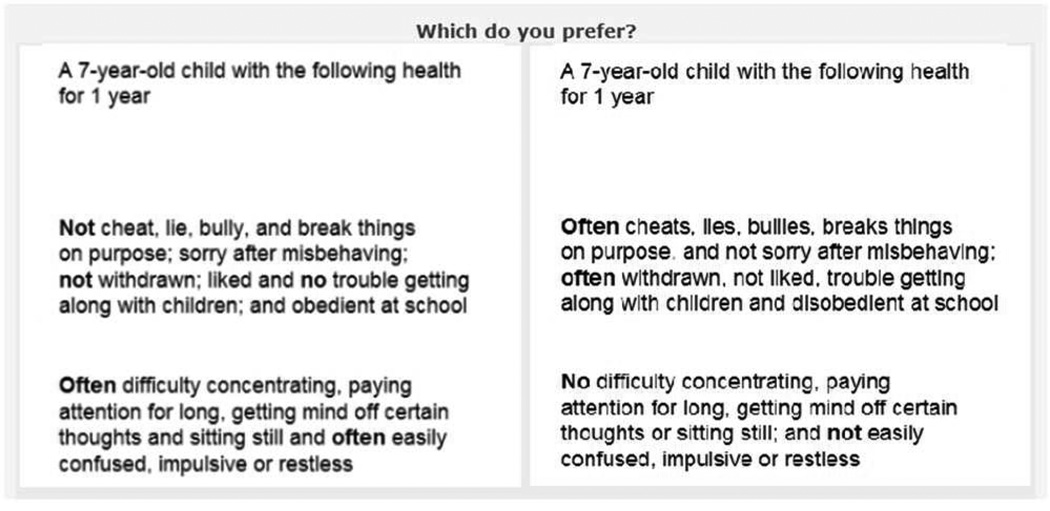

Class Pairs

In addition to comparing items and domains within the BPI, we selected class pairs to allow for the identification of independent effects of class. We grouped the six domains into three classes: Emotional Health (AD, HS, ID), Communication and Learning Problems (HY), and Behavioral and Social Development (AS, PS). All classes were compared to each other at both one-step and two-step changes: ([1,2],[2,1]), ([1,2],[3,2]), ([1,3],[3,1]), ([2,3],[2,1]), ([2,3],[3,2]), resulting in five pairs for each class comparison (Table 12). In Figure 2, for example, emotional health is traded off for communication and learning problems: ADj,1+HSj,k+IDj,k vs. HYj,k.

Lifespan Pairs

Lifespan pairs involved trading 4 behavioral problems and 1 of 15 lifespan combinations (Table 13). For example, in Figure 1, respondents chose between Dur1×(ADj,k+HSj,k+IDj,k) and Y3 for a 7-year-old child (age7). Clearly, the proportion that chose loss in lifespan decreased as the loss in lifespan increased (from top to bottom of each column).

Section 4: Econometrics

Econometrics aims to give empirical content to economic relations. In health valuation, the econometric specification describes how preference evidence from all pairs can be interpreted to infer the demand for health. With this knowledge, the resulting model can predict preferences about combinations of health attributes not included in the experimental design (i.e., out-of-sample prediction). Before introducing the preference evidence and specification, this section begins by reviewing a few working definitions in health valuation.

As a working definition, health encompasses all measurable feelings (e.g., depression), ability (e.g., confined to bed), and anatomy (e.g., missing a leg) and is a fundamental component of a person’s utility function as defined by microeconomic theory. A health outcome is a difference in health that afflicts a person with a start and end time (e.g., starting today, you have 30 days with moderate pain). Whether symptoms or losses in HRQoL, all health outcomes have value. Value is defined by the choices within a target population (i.e., P(A>B)) in response to preference questions (e.g., Which do you prefer?). A mantra within health preference research is choice defines value. The purpose of a health valuation study is to estimate how differences in outcomes influence choice (i.e., ΔP(A>B)/ΔA) within a target population (i.e., demand curve). This analysis is largely informed by choices between hypothetical health outcomes, because rarely can we observe whether potential outcomes directly influence choices. Furthermore, it is virtually impossible and/or impractical to collect choice data on all combinations of attributes and for each person individually; therefore, value estimation is commonly motivated by the need for generalization across attributes and persons.

Preference Evidence

A paired comparison dataset includes the choices, yk, for each pair, k. To identify the minimum sample size required to reasonably measure preference in the kth pair, this study applies the NP5 rule, which states that given a pair sample size, Nk, and a population probability, pk, the sample probability, ȳk, is approximately normally distributed if Nk × pk > 5 or Nk × (1−pk) < 5. The NP5 rule is based on the central limit theorem (CLT) adjusted for binomial data. By restricting pk between 0.1 and 0.9 and collecting samples sizes above 50 choices for each pair (Nk >50), ȳk is approximately normally distributed by CLT.

In complement to the restrictions on pk and Nk, the study applied demographic quotas on each pair sample, Nk. To improve concordance with the 2010 US census, each pair sample included a minimum number of adults from 18 quotas: 2 genders (Male, Female), 3 age groups in years (18 to 34, 35 to 54, 55 or older), and 3 race/ethnicity groups (Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; White or other, non-Hispanic). Table 14 shows the prevalence of these categories according to the US 2010 Census. This quota sampling method enforces a minimum amount of demographic diversity in each pair sample.

Value Estimation

In health valuation, an econometric estimation requires an objective function, a cumulative density function (CDF) and an index function. An objective function, L(Nk, ȳk, pk), links data, Nk and ȳk, to probabilities, pk. The CDF links pk to pair attributes, CDF(A,B), and is “best considered merely an empirical curve, employed for the succinct statistical reduction of the data, of great descriptive utility, but without theoretical significance” (Berkson 1951). The index function is the mathematical relationship between the attributes, XA, and the parameters, β, (A = XA’β; Section 2). When combined, the estimation entails the maximization of L(Nk, ȳk, CDF(A,B)) to identify the parameters, β. In addition to parameters in the index function, β, the CDF may also have ancillary parameters to create a more flexible functional form (e.g., scaling parameter).

In rare cases, an econometric estimation is not necessary to define the relative value of two health outcomes. Indifference within a target population (i.e., P(A>B)=0.5) implies equivalence of the alternatives (i.e., A=B). Therefore, a preference elicitation task may directly measure value if it can identify the indifference point. This reliance on indifference identification has three advantages: (1) rotating alternatives left and right has no effect on P(A>B); (2) inequalities conflate preference and uncertainty, but indifferences do not; and (3) 50% minimizes loss of information, because the second largest and smallest possible pk is bounded by sample size. Yet, all samples with an even number of choices can estimate pk=50%. The identification of the indifference point is arduous and may not be feasible or even possible. When the probability is greater than or less than 50%, econometric estimation is required to translate inequalities into values.

Scaling, Scope, and Unanimity

The specification of an econometric estimation for health valuation must take into consideration three issues: scale, scope, and unanimity. Scope refers to the assumption that attributes in common to both alternatives cancel. Scale refers to the assumption that only the relative value of attributes matters (i.e., scale cancels). Scale and scope assumptions determine the measure of difference in the econometric specification, namely how the two index functions, A and B, are incorporated into the CDF: additive (A–B) or multiplicative (A/B). An additive specification assumes a common scale for all alternatives, but a multiplicative specification allows scale to cancel within the pair (i.e., (scale × A)/(scale × B) = A/B). Likewise, scope (a.k.a., the “big” picture or context; i.e., attributes in common to both A and B) cancels in an additive difference (i.e., (scope + A) − (scope + B) = A–B), but not in a multiplicative difference. Although scale and scope may be informative (i.e., these assumptions may fail), it is advantageous in health valuation that scale and scope cancel within the CDF.

Why is scale a problem? If we use an additive difference specification, pairs with the same probability have the same difference in value. However, the comparison of two mild outcomes may have the same probability of a comparison of two severe outcomes; yet, difference in the mild values is much smaller than the difference in the severe values. The additive specification, A–B, does not adjust for scale, but scale cancels in the multiplicative specification, A/B.

Why is scope a problem? Adding the same attribute to both A and B changes the scope, but typically has little effect on the choice. Under a multiplicative specification, A/B, pk depends on the ratio in value. For example, including more pain to both A and B would attenuate the ratio toward one by construction (i.e., (more pain + A) / (more pain + B)), even though this added pain likely affects choice because it is in both A and B. The multiplicative specification does not adjust for scope, A/B, but scope cancels in the additive specification, A–B.

This study applies an econometric specification that accommodates for scale and scope. Scope is controlled within the index function by limiting A to be just the attribute worse for the left alternative and limiting B to be just the attribute worse for the right alternative (i.e., inherently removing scope from both A and B; Section 2). Scale is controlled within the CDF by the placing of A and B into a ratio (i.e., scale cancels), namely CDF(A,B)=1/(1+B/A).

To exemplify scope, Figure 5 shows the paired comparison trading off behavioral and social development problems (e.g., bullying, breaking things, disobedience) for anxiety and depression (e.g., too dependent, feels unloved, worthless, and tense). Regardless of the choice between A and B, the person will have at least some problems with anxiety and depression (i.e., scope). In the estimation, the scope cancels from both A5 and B5; therefore, A5 is ADj,2+HS,2+IDj,2 and B5 is ASj,1+ PSj,1. To exemplify scale, Figure 6 shows the tradeoff between frequent behavioral and social development problems and frequent communication and learning problems. In this case, A6 is HYj,1+HYj,2 and B6 is ASj,1+PSj,1+ASj,2+ PSj,2. Clearly, the one-step changes in Figure 5 are on a different scale than the two-step changes in Figure 6; nevertheless, the two pairs may have the same probability. If Figure 5 has the same probability as Figure 6, the model infers that the ratio, B5/A5, equals the ratio, B6/A6, (i.e., scale cancels). Using this econometric specification adjusts for both scale and scope.

Figure 5 Example of scope.

Figure 6 Example of scale.

Unanimity is the case where the pk is 1 or 0. In economic theory, choices may be non-probabilistic (e.g., logically ranked), and the estimator must accommodate this case in both the objective function and CDF specification. CDFs based on additive differences (e.g., logit) typically cannot allow for unanimity because the difference is not defined when the pk is 1 or 0. Additionally, maximum likelihood estimation cannot accommodate unanimity (i.e., ln(Lk)= Nk × ȳk × ln(pk) + Nk (1-ȳk) × ln(1-pk) ). For this reason, this study applies minimum chi-squared estimation (i.e., Lk = −0.5 × Nk × (ȳk - pk)2 × (ȳk×(1-ȳk)) −1). Minimum chi-squared estimation has the same first derivative as maximum likelihood estimation, except that it weighs the errors by precision based ȳk instead of pk; hence pk can be 1 or 0.

In combination, the econometric estimation in this study addresses issues with scale, scope, and unanimity by use of minimized chi-squared with ratio-based CDFs.

Table 1.

Pivot Descriptions and Parameters

| Pivot Descriptions | Parameters |

|---|---|

| A 7-year-old child with the following health for 1 year | Age7, Dur1 |

| A 7-year-old child with the following health for 2 years | Age7, Dur2 |

| A 10-year-old child with the following health for 1 year | Age10, Dur1 |

| A 10-year-old child with the following health for 2 years | Age10, Dur2 |

Dur=duration.

Table 2.

BPI Attributes and Their Values

| Class/Domain/Item | Better Health | Worse Health | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Health | ||||

| Anxiety/Depression | 1 | No sudden changes in mood or feeling | Sometimes sudden changes in mood or feeling | AD1,1 |

| Sometimes sudden changes in mood or feeling | Often sudden changes in mood or feeling | AD1,2 | ||

| No sudden changes in mood or feeling | Often sudden changes in mood or feeling | AD1,1+AD1,2 | ||

| 2 | Not feel or complain that no one loves him/her | Sometimes feels or complains that no one loves him/her | AD2,1 | |

| Sometimes feels or complains that no one loves him/her | Often feels or complains that no one loves him/her | AD2,2 | ||

| Not feel or complain that no one loves him/her | Often feels or complains that no one loves him/her | AD2,1+AD2,2 | ||

| 3 | Not too fearful or anxious | Sometimes too fearful or anxious | AD3,1 | |

| Sometimes too fearful or anxious | Often too fearful or anxious | AD3,2 | ||

| Not too fearful or anxious | Often too fearful or anxious | AD3,1+AD3,2 | ||

| 4 | Not feel worthless or inferior | Sometimes feels worthless or inferior | AD4,1 | |

| Sometimes feels worthless or inferior | Often feels worthless or inferior | AD4,2 | ||

| Not feel worthless or inferior | Often feels worthless or inferior | AD4,1+AD4,2 | ||

| 5 | Not unhappy, sad, or depressed | Sometimes unhappy, sad, or depressed | AD5,1 | |

| Sometimes unhappy, sad, or depressed | Often unhappy, sad, or depressed | AD5,2 | ||

| Not unhappy, sad, or depressed | Often unhappy, sad, or depressed | AD5,1+AD5,2 | ||

| Headstrong | 1 | Not rather high strung, tense and nervous | Sometimes rather high strung, tense and nervous | HS1,1 |

| Sometimes rather high strung, tense and nervous | Often rather high strung, tense and nervous | HS1,2 | ||

| Not rather high strung, tense and nervous | Often rather high strung, tense and nervous | HS1,1+HS1,2 | ||

| 2 | Not argue too much | Sometimes argues too much | HS2,1 | |

| Sometimes argues too much | Often argues too much | HS2,2 | ||

| Not argue too much | Often argues too much | HS2,1+HS2,2 | ||

| 3 | Not disobedient at home | Sometimes disobedient at home | HS3,1 | |

| Sometimes disobedient at home | Often disobedient at home | HS3,2 | ||

| Not disobedient at home | Often disobedient at home | HS3,1+HS3,2 | ||

| 4 | Not stubborn, sullen or irritable | Sometimes stubborn, sullen and irritable | HS4,1 | |

| Sometimes stubborn, sullen and irritable | Often stubborn, sullen and irritable | HS4,2 | ||

| Not stubborn, sullen or irritable | Often stubborn, sullen and irritable | HS4,1+HS4,2 | ||

| 5 | Not a very strong temper and not lose it easily | Sometimes a very strong temper and sometimes loses it easily | HS5,1 | |

| Sometimes a very strong temper and sometimes loses it easily | Often a very strong temper and often loses it easily | HS5,2 | ||

| Not a very strong temper and not lose it easily | Often a very strong temper and often loses it easily | HS5,1+HS5,2 | ||

| Immature Dependency |

1 | Not cling to adults | Sometimes clings to adults | ID1,1 |

| Sometimes clings to adults | Often clings to adults | ID1,2 | ||

| Not cling to adults | Often clings to adults | ID1,1+ID1,2 | ||

| 2 | Not cry too much | Sometimes cries too much | ID2,1 | |

| Sometimes cries too much | Often cries too much | ID2,2 | ||

| Not cry too much | Often cries too much | ID2,1+ID2,2 | ||

| 3 | Not demand a lot of attention | Sometimes demands a lot of attention | ID3,1 | |

| Sometimes demands a lot of attention | Often demands a lot of attention | ID3,2 | ||

| Not demand a lot of attention | Often demands a lot of attention | ID3,1+ID3,2 | ||

| 4 | Not too dependent on others | Sometimes too dependent on others | ID4,1 | |

| Sometimes too dependent on others | Often too dependent on others | ID4,2 | ||

| Not too dependent on others | Often too dependent on others | ID4,1+ID4,2 | ||

| Communication and Learning Problems | ||||

| Hyperactive | 1 | No difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | Sometimes difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | HY1,1 |

| Sometimes difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | Often difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | HY1,1 | ||

| No difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | Often difficulty concentrating or paying attention for long | HY1,1+HY1,2 | ||

| 2 | Not easily confused or not seem to be in a fog | Sometimes easily confused or sometimes seems to be in a fog | HY2,1 | |

| Sometimes easily confused or sometimes seems to be in a fog | Often easily confused or often seems to be in a fog | HY2,2 | ||

| Not easily confused or not seem to be in a fog | Often easily confused or often seems to be in a fog | HY2,1+HY2,2 | ||

| 3 | Not impulsive and not act without thinking | Sometimes impulsive or sometimes acts without thinking | HY3,1 | |

| Sometimes impulsive or sometimes acts without thinking | Often impulsive or often acts without thinking | HY3,2 | ||

| Not impulsive and not act without thinking | Often impulsive or often acts without thinking | HY3,1+HY3,2 | ||

| 4 | Not a lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts (no obsessions) | Sometimes a lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts (sometimes has obsessions) | HY4,1 | |

| Sometimes a lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts (sometimes has obsessions) | Often a lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts (often has obsessions) | HY4,2 | ||

| Not a lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts (no obsessions) | Often a lot of difficulty getting his/her mind off certain thoughts (often has obsessions) | HY4,1+HY4,2 | ||

| 5 | Not restless, not overly active and can sit still | Sometimes restless, sometimes overly active and sometimes cannot sit still | HY5 | |

| Sometimes restless, sometimes overly active and sometimes cannot sit still | Often restless, often overly active and often cannot sit still | HY5 | ||

| Not restless, not overly active and can sit still | Often restless, often overly active and often cannot sit still | HY5 | ||

| Behavioral and Social Development | ||||

| Antisocial | 1 | Not cheat and not tell lies | Sometimes cheats or sometimes tells lies | AS1,1 |

| Sometimes cheats or sometimes tells lies | Often cheats or often tells lies | AS1,2 | ||

| Not cheat and not tell lies | Often cheats or often tells lies | AS1,1+AS1,2 | ||

| 2 | Not bully, cruel and mean to others | Sometimes bullies, cruel and mean to others | AS2,1 | |

| Sometimes bullies, cruel and mean to others | Often bullies, cruel and mean to others | AS2,2 | ||

| Not bully, cruel and mean to others | Often bullies, cruel and mean to others | AS2,1+AS2,2 | ||

| 3 | Sorry after misbehaving | Sometimes not sorry after misbehaving | AS3,1 | |

| Sometimes not sorry after misbehaving | Often not sorry after misbehaving | AS3,2 | ||

| Sorry after misbehaving | Often not sorry after misbehaving | AS3,1+AS3,2 | ||

| 4 | Not break things on purpose, | Sometimes breaks things on purpose, | AS4,1 | |

| not deliberately destroy his/her own or another’s things | sometimes deliberately destroys his/her own or another’s things | |||

| Sometimes breaks things on purpose, | Often breaks things on purpose, | AS4,2 | ||

| sometimes deliberately destroys his/her own or another’s things | often deliberately destroys his/her own or another’s things | |||

| Not break things on purpose, | Often breaks things on purpose, | AS4,1+AS4,2 | ||

| not deliberately destroy his/her own or another’s things | often deliberately destroys his/her own or another’s things | |||

| 5 | Not disobedient at school | Sometimes disobedient at school | AS5,1 | |

| Sometimes disobedient at school | Often disobedient at school | AS5,2 | ||

| Not disobedient at school | Often disobedient at school | AS5,1+AS5,2 | ||

| 6 | No trouble getting along with teachers | Sometimes trouble getting along with teachers | AS6,1 | |

| Sometimes trouble getting along with teachers | Often trouble getting along with teachers | AS6,2 | ||

| No trouble getting along with teachers | Often trouble getting along with teachers | AS6,1+AS6,2 | ||

| Peer Conflict/ Social Withdrawal |

1 | No trouble getting along with other children | Sometimes trouble getting along with other children | PS1,1 |

| Sometimes trouble getting along with other children | Often trouble getting along with other children | PS1,2 | ||

| No trouble getting along with other children | Often trouble getting along with other children | PS1,1+PS1,2 | ||

| 2 | Liked by other children | Sometimes not liked by other children | PS2,1 | |

| Sometimes not liked by other children | Often not liked by other children | PS2,2 | ||

| Liked by other children | Often not liked by other children | PS2,1+PS2,2 | ||

| 3 | Not withdrawn and gets involved with others | Sometimes withdrawn and sometimes does not get involved with others | PS3,1 | |

| Sometimes withdrawn and sometimes does not get involved with others | Often withdrawn and often does not get involved with others | PS3,2 | ||

| Not withdrawn and gets involved with others | Often withdrawn and often does not get involved with others | PS3,1+PS3,2 | ||

AD=Anxiety/Depression; HS=Headstrong; ID=Immature Dependency; HY=Hyperactive; AS=Antisocial; PS=Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal; j=item; k=level

Table 3.

Lifespan Attributes and Their Values

| Labels and Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 10 years then dies | - |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years, 11 months, and 23 days | D7 |

| (1 week less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years, 11 months, and 16 days then dies | D14 |

| (2 weeks less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years, 11 months, and 9 days then dies | D21 |

| (3 weeks less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years and 11 months then dies | M1 |

| (1 month less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years and 10 months then dies | M2 |

| (2 months less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years and 9 months then dies | M3 |

| (3 months less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years and 8 months then dies | M4 |

| (4 months less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years and 6 months then dies | M6 |

| (6 months less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years and 3 months then dies | M9 |

| (9 months less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 9 years then dies | Y1 |

| (1 year less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 8 years then dies | Y2 |

| (2 years less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 7 years then dies | Y3 |

| (3 years less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 6 years then dies | Y4 |

| (4 years less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 5 years then dies | Y5 |

| (5 years less than 10 years) | |

| Afterwards, the child has no health problems for 4 years then dies | Y6 |

| (6 years less than 10 years) |

Dk, Mk, and Yk represent the reduction in a 10-year lifespan in days, months, and years, respectively, with an index, k, representing the number of time units.

Table 4.

Item Pairs ([1,2],[2,1]) or ([2,3],[3,2]): AD

| Alternative A | Alternative B | Pivot | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

| 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years | ||

| AD2,1 | AD1,1 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| AD2,2 | AD1,2 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.53 |

| AD3,1 | AD1,1 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| AD3,1 | AD2,1 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.53 |

| AD3,2 | AD1,2 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.51 |

| AD3,2 | AD2,2 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.47 |

| AD4,1 | AD1,1 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.69 |

| AD4,1 | AD2,1 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.63 |

| AD4,1 | AD3,1 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.61 |

| AD4,2 | AD1,2 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.59 |

| AD4,2 | AD2,2 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.69 |

| AD4,2 | AD3,2 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| AD5,1 | AD1,1 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| AD5,1 | AD2,1 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.49 |

| AD5,1 | AD3,1 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.57 |

| AD5,1 | AD4,1 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| AD5,2 | AD1,2 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.92 |

| AD5,2 | AD2,2 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.65 |

| AD5,2 | AD3,2 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| AD5,2 | AD4,2 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.45 |

The results represent the proportion of the respondents who chose Alternative B over Alternative A. AD=Anxiety/Depression.

Table 5.

Item Pairs ([1,2],[2,1]) or ([2,3],[3,2]): HS

| Alternative A | Alternative B | Pivot | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

| 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years | ||

| HS2,1 | HS1,1 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| HS2,2 | HS1,2 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.42 |

| HS3,1 | HS1,1 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.37 |

| HS3,1 | HS2,1 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.54 |

| HS3,2 | HS1,2 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.67 |

| HS3,2 | HS2,2 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| HS4,1 | HS1,1 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.44 |

| HS4,1 | HS2,1 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.66 |

| HS4,1 | HS3,1 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.52 |

| HS4,2 | HS1,2 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| HS4,2 | HS2,2 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.48 |

| HS4,2 | HS3,2 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.32 |

| HS5,1 | HS1,1 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| HS5,1 | HS2,1 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.81 |

| HS5,1 | HS3,1 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.72 |

| HS5,1 | HS4,1 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.78 |

| HS5,2 | HS1,2 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.68 |

| HS5,2 | HS2,2 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.75 |

| HS5,2 | HS3,2 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| HS5,2 | HS4,2 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.71 |

The results represent the proportion of the respondents who chose Alternative B over Alternative A. HS = Headstrong.

Table 6.

Item Pairs ([1,2],[2,1]) or ([2,3],[3,2]): HY

| Pivot | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

| Alternative A | Alternative B | 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years |

| HY2,1 | HY1,1 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.74 |

| HY2,2 | HY1,2 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.61 |

| HY3,1 | HY1,1 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.49 |

| HY3,1 | HY2,1 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| HY3,2 | HY1,2 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.60 |

| HY3,2 | HY2,2 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| HY4,1 | HY1,1 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.62 |

| HY4,1 | HY2,1 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.49 |

| HY4,1 | HY3,1 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.59 |

| HY4,2 | HY1,2 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| HY4,2 | HY2,2 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| HY4,2 | HY3,2 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| HY5,1 | HY1,1 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.49 |

| HY5,1 | HY2,1 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.24 |

| HY5,1 | HY3,1 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.52 |

| HY5,1 | HY4,1 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.34 |

| HY5,2 | HY1,2 | 0.45 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.52 |

| HY5,2 | HY2,2 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

| HY5,2 | HY3,2 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| HY5,2 | HY4,2 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.42 |

The results represent the proportion of the respondents who chose Alternative B over Alternative A. HY=Hyperactivity.

Table 7.

Item Pairs ([1,2],[2,1]) or ([2,3],[3,2]): ID

| Pivot | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

| Alternative A | Alternative B | 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years |

| ID2,1 | ID1,1 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.74 |

| ID2,2 | ID1,2 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.66 |

| ID3,1 | ID1,1 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.71 | 0.63 |

| ID3,1 | ID2,1 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.42 |

| ID3,2 | ID1,2 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.50 |

| ID3,2 | ID2,2 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.39 |

| ID4,1 | ID1,1 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| ID4,1 | ID2,1 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| ID4,1 | ID3,1 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.60 |

| ID4,2 | ID1,2 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| ID4,2 | ID2,2 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.33 |

| ID4,2 | ID3,2 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

The results represent the proportion of the respondents who chose Alternative B over Alternative A. ID=Immature Dependency.

Table 8.

Item Pairs ([1,2],[2,1]) or ([2,3],[3,2]): AS

| Pivot | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

| Alternative A | Alternative B | 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years |

| AS2,1 | AS1,1 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.73 |

| AS2,2 | AS1,2 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.61 |

| AS3,1 | AS1,1 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| AS3,1 | AS2,1 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| AS3,2 | AS1,2 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.34 |

| AS3,2 | AS2,2 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| AS4,1 | AS1,1 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.48 |

| AS4,1 | AS2,1 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| AS4,1 | AS3,1 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| AS4,2 | AS1,2 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.42 |

| AS4,2 | AS2,2 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.35 |

| AS4,2 | AS3,2 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.50 |

| AS5,1 | AS1,1 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| AS5,1 | AS2,1 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| AS5,1 | AS3,1 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.32 |

| AS5,1 | AS4,1 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.18 |

| AS5,2 | AS1,2 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

| AS5,2 | AS2,2 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.29 |

| AS5,2 | AS3,2 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.66 |

| AS5,2 | AS4,2 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.47 |

| AS6,1 | AS1,1 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.33 |

| AS6,1 | AS2,1 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| AS6,1 | AS3,1 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.33 |

| AS6,1 | AS4,1 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.28 |

| AS6,1 | AS5,1 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.57 |

| AS6,2 | AS1,2 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.24 |

| AS6,2 | AS2,2 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| AS6,2 | AS3,2 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| AS6,2 | AS4,2 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.31 |

| AS6,2 | AS5,2 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.30 |

The results represent the proportion of the respondents who chose Alternative B over Alternative A. AS=Antisocial.

Table 9.

Item Pairs ([1,2],[2,1]) or ([2,3],[3,2]): PS

| Pivot | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

| Alternative A | Alternative B | 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years |

| PS2,1 | PS1,1 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.27 |

| PS2,1 | PS1,1 (2 of 2) | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.44 |

| PS2,2 | PS1,2 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.62 |

| PS2,2 | PS1,2 (2 of 2) | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.44 |

| PS3,1 | PS1,1 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.42 |

| PS3,1 | PS1,1 (2 of 2) | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.47 |

| PS3,1 | PS2,1 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| PS3,1 | PS2,1 (2 of 2) | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.57 |

| PS3,2 | PS1,2 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.43 |

| PS3,2 | PS1,2 (2 of 2) | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.38 |

| PS3,2 | PS2,2 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| PS3,2 | PS2,2 (2 of 2) | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.42 |

The results represent the proportion of the respondents who chose Alternative B over Alternative A. PS=Peer Conflict/Social Withdrawal.

Table 10.

Item Pairs: First Change to a Second Change ([2,2],[3,1])

| 7-year-old | 10-year-old | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years | ||

| AD2,1 | AD1,2 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.42 |

| AD3,1 | AD1,2 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.02 |

| AD4,1 | AD1,2 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.41 |

| AD5,1 | AD1,2 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.35 |

| AS1,1 | AS3,2 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.58 |

| AS2,1 | AS3,2 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| AS4,1 | AS3,2 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.51 |

| AS5,1 | AS3,2 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.41 |

| AS6,1 | AS3,2 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.28 |

| HS1,1 | HS2,2 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

| HS1,1 | HS4,2 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.40 |

| HS1,1 | HS5,2 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| HS3,1 | HS2,2 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.15 |

| HS4,1 | HS2,2 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| HS5,1 | HS2,2 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

| HY2,1 | HY1,2 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.44 |

| HY2,1 | HY3,2 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.36 |

| HY2,1 | HY5,2 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| HY3,1 | HY5,2 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| HY4,1 | HY1,2 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.51 |

| HY4,1 | HY3,2 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.38 |