Abstract

Purpose

The current study sought to expand our understanding of relapse mechanisms by identifying the independent and interactive effects of real-time risk factors on temptations and the ability to resist temptations in smokers during a quit attempt.

Procedures

This study was a secondary analysis of data from 109 adult, treatment-seeking daily smokers. Ecological momentary assessment data was collected 4 times a day for 21 days following a quit attempt and was used to assess affect, urge, impulsiveness, recent cigarette exposure, and alcohol use as predictors of temptations to smoke and smoking up to 8 hours later. All smokers received nicotine replacement therapy and smoking cessation counseling.

Findings

In multinomial hierarchical linear models, there were significant main (agitation Odds Ratio (OR)=1.22, 95%CI=1.02-1.48; urge OR=1.60, 95%CI=1.35-1.92; nicotine dependence measured by WISDM OR=1.04, 95%CI=1.01-1.08) and interactive effects (agitation x urge OR=1.12,95%CI=1.01-1.27; urge x cigarette exposure OR=1.38, 95%CI=1.10-1.76; positive affect x impulsiveness OR=2.44, 95%CI=1.02-5.86) on the odds of temptations occurring, relative to abstinence without temptation. In contrast, prior smoking (OR=3.46, 95%CI=2.58-4.63), higher distress (OR=1.30, 95%CI=1.06-1.60), and recent alcohol use (OR=3.71, 95%CI=1.40-9.89) predicted smoking versus resisting temptation, and momentary impulsiveness was related to smoking for individuals with higher baseline impulsiveness (OR=1.12, 95%CI=1.04-1.22).

Conclusions

The risk factors and combinations of factors associated with temptations and smoking lapses differ, suggesting a need for separate models of temptation and lapse.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking cessation, ecological momentary assessment, temptation, relapse

1. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States (CDC, 2008; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). Although many smokers attempt to quit annually, roughly 95% of smokers who quit for 24 hours return to smoking within 3 months (CDC, 2011; Fiore et al., 2008). Understanding relapse processes is critical to identifying intervention targets and improving cessation rates.

In particular, research is needed to understand the proximal, phasic influences on smoking. Differences in the determinants of motivational lapses (i.e., temptations to smoke) and behavioral lapses (i.e., a return to smoking after quitting) may inform treatment delivery. Identifying risk factors for motivational lapses may suggest targets to strengthen a smoker's confidence or commitment to quitting. Likewise, identifying factors that differentiate episodes when smokers resist a temptation and those when they yield to temptation and smoke may help identify early warning signs of cessation failure.

Several studies have attempted to identify antecedents of temptations and smoking using ecological momentary assessment (EMA; Stone and Shiffman, 1994) data collected several times daily from smokers attempting to quit (Shiffman, 2009; Shiffman et al., 1996, 2007). Research suggests negative affect and urge differentiate temptations and smoking (Shiffman et al., 1996), however extant studies are limited to comparisons of smokers’ first lapse and first temptation event. Each smoking opportunity after quitting is a critical choice point to smoke or abstain, and smokers may have multiple periods of abstinence, temptation, and smoking while quitting (Baker et al., 2011; Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983). Studying the antecedents to multiple temptation and smoking events after quitting, while controlling for smoking status, may build on past research and identify factors that influence smoking behavior more generally.

Additionally, much of the research to date has examined risk factors in independent, not combined models. A recent study by Lam and colleagues (2014) was among the first to investigate ways relapse risk factors interact. Their results suggested smoking urge significantly interacted with negative affect and being around smokers to influence lapse risk. Specifically, states of negative affect and exposure to others smoking were more strongly associated with lapses in times of low vs. high urge. While these findings suggest the importance of examining multiple predictor models and interactive effects, all risk factors and outcomes were examined concurrently, so the direction of the effect is unclear (i.e., it is possible low urge is due to a recent lapse instead of the cause of smoking). Studying ways risk factors combine to influence smoking risk before smoking occurs may improve our understanding of lapse mechanisms and suggest just-in-time interventions.

The current project fills gaps in the literature using time-lagged hierarchical linear modeling to identify risk factors of later temptations and smoking. Additionally, this project is one of the first to examine how well-known relapse risk factors (i.e., affect, urge, and environmental context) interact to predict later temptations or lapses during a quit attempt. According to the relapse model put forth by Marlatt and Gordon (1985), relapse is preceded by a high-risk situation which can include specific emotional and physiological states (i.e., affect, urge) and environmental cues. Available research further supports the role of these risk factors as predictors of smoking behavior. Specifically, smoking to alleviate negative affect (i.e., withdrawal) may maintain smoking over time (Baker et al., 2004), and momentary negative affect predicts temptations and lapses (Minami et al., 2014; Shiffman et al., 1996). At present, it is unknown how positive affect relates to the occurrence of temptations and success resisting them. However, there is evidence that positive affect is inversely related to urge intensity (Doran et al., 2008) and smoking lapse (Strong et al., 2009), independent of negative affect, suggesting a protective role against smoking after quitting. Furthermore, craving or urge to smoke is a central process motivating smoking behavior (Baker et al., 1987; Robinson and Berridge, 1993; Tiffany, 1990) and urge intensity predicts temptations and lapses after quitting (Shiffman et al., 1996). Additionally, aspects of the environment, such as being around other smokers and drinking alcohol, are known predictors of temptations and smoking (Kahler et al., 2009; Shiffman et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 2009).

Prior studies have modeled these risk factors independently, however this may provide limited information about lapse processes because these factors may combine in unique ways to influence risk. For example, craving is theorized to be central to relapse risk, yet it only explains 6% of the variance in smoking behavior across laboratory studies (Tiffany et al., 2009), and smokers often relapse despite using pharmacotherapies designed to attenuate craving intensity (Fiore et al., 2008). These results highlight that urge alone only partially explains smoking behavior, suggesting that it may be important to consider how other momentary factors, such as mood or context, interact with urge to better explain the influence on smoking behavior.

The primary aim of the current project is to identify ways affect, urge, and environmental context interact to influence the occurrence of later temptations and smoking after a target quit smoking day. We contrasted episodes of strong temptation to episodes of untempted abstinence to identify factors influencing temptation risk. We also contrasted episodes of smoking to episodes of strong temptations without smoking to identify factors related specifically to the inability to resist smoking. Based on prior research, we expected negative affect, urge, access to cigarettes, and recent alcohol use would be positively related to temptation and smoking risk, while we expected positive affect would be protective against risk (e.g., Kahler et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2014; Shiffman et al., 1996; Strong et al., 2009). We hypothesized a priori two-way interactions between negative affect, urge, and context. Specifically, we expected high momentary negative affect and urge would synergistically increase risk for later temptations (vs. abstinence) or smoking (vs. temptations) by increasing the incentive value of smoking. We expected heightened urge or negative affect would lead to smoking more often in the presence (vs. absence) of cigarettes or when smokers were disinhibited from recent alcohol use (vs. no alcohol use).

A secondary aim was to examine the influence of impulsiveness on temptations and smoking after quitting. Impulsiveness has been conceptualized as a stable trait differing between individuals, although recent research indicates facets of impulsiveness vary within individuals and are influenced by mood state (Weafer et al., 2013), nicotine deprivation (Field et al., 2006; Mitchell, 2004), and stress exposure (Schepis et al., 2011). Therefore, impulsiveness may be a dynamic, state-dependent construct. To investigate the relation between state and trait impulsiveness, we explored an EMA measure of behavioral impulsiveness as a predictor of temptations and smoking and examined trait impulsiveness as a moderator of this effect. We expected a stronger relation between momentary impulsiveness and smoking for individuals with high (vs. low) baseline impulsiveness. We also explored secondary two-way interactions between behavioral impulsiveness and affect, urge, and context. We expected impulsiveness would undermine the protective effect of positive affect and would exacerbate risk in combination with negative affect, urge, access to cigarettes, or recent alcohol consumption.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

This project analyzed EMA data collected for 21 days post-quit from 109 treatment-seeking smokers engaged in a quit-attempt. All participants received nicotine lozenge treatment (2mg or 4mg for 12-weeks based on their time to first cigarette in the morning) and counseling (four 15-minute sessions). Eligibility criteria for participation included: at least 18 years old; English literate; heavy smoking (≥ 10 cigarettes per day for ≥ 6 months with expired carbon monoxide ≥ 8 parts per million); motivation to quit smoking (≥ 6 on a 10-point scale); no lozenge contraindications (e.g., heart disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding); no bipolar or psychosis history; not living with study participants; and no current use of other tobacco, cessation treatments, marijuana, or illegal drugs.

2.2 Procedure

Participants were screened for eligibility by phone and attended an orientation to complete consent procedures, baseline assessments, and learn to use the EMA device (Palm Z22 Palmtop computers, Palm Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Participants attended 5 weekly visits from one week pre-quit to three weeks post-quit and received feedback about EMA adherence.

2.3 Baseline Assessments

Pre-quit baseline measures assessed nicotine dependence [Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68; Piper et al., 2004) and Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al., 1991)], smoking history, and demographics. Other self-report questionnaires assessed positive and negative affect [Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Crawford and Henry, 2004; Watson et al., 1988), withdrawal symptom severity (Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale (WSWS; Welsch et al., 1999), and trait impulsiveness (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995)].

2.4 Ecological Momentary Assessments

Participants were prompted four times daily to complete 5-minute EMA reports. Alarms were set to occur at least 30 minutes apart at random times within four equal intervals in the waking day. The prompt signaled participants to answer several self-report items and complete a brief momentary impulsiveness assessment, described below. We chose to use random EMA assessment only rather than ask participants to prompt reports of events following temptations or smoking because, unlike prior studies that examined only the first lapse post-quit (e.g., Shiffman et al., 1996), we wanted to assess smoking and temptations occurring over several weeks post-quit and aimed to reduce participant burden and possible assessment reactivity over time (McCarthy et al., 2015).

Participants were encouraged to respond to the prompt within 30 minutes. “Late” versus “on-time” (i.e., within 30 minutes following the prompt) reports were more likely to show elevated urge or positive affect and recent alcohol consumption, stress, strong temptation, and smoking opportunity. All completed reports were analyzed to avoid systematic bias by excluding late reports. In total, 85% of prompted reports were completed, although completion rates varied by subject (M=79.6%, SD=16.6%).

2.4.1 Momentary Affect

Items derived from the PANAS and WSWS were used in EMA reports to assess affect and withdrawal symptoms. Smokers rated each item from 1 (very slightly or not at all/disagree) to 5 (extremely/agree) based on their experience in the 15 minutes prior to the prompt. Confirmatory factor analysis suggested a best-fitting model with two correlated negative affect factors: distress comprised of sad mood items “sad or depressed”, “distressed”, and “upset”; and agitation comprised of tense arousal items “impatient”, “tense or anxious” and “restless”; and one correlated positive affect factor with items “I have felt enthusiastic” and “I have felt interested”. Thus, negative affect was examined as two separate factors based on these empirical and conceptual distinctions.

2.4.2 Momentary Urge

Urge to smoke was assessed by two questions “I have trouble getting cigarettes off my mind” and “I have been bothered by the desire to smoke a cigarette”. Smokers rated each item from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree) based on their experience in the 15 minutes prior to the prompt. Scores on these items were averaged as an index of momentary urge. These were the best performing items in previous research with similar EMA assessments of urge (McCarthy et al., 2008).

2.4.3 Cigarette Exposure

Recent cigarette exposure was assessed by asking whether or not smokers had an easy opportunity to smoke or had been with someone who was smoking in the last 15 minutes. Recent cigarette exposure was coded as 1=yes or 0=no if subjects responded “yes” to either question.

2.4.4 Recent Alcohol Use

Recent alcohol use was coded 1=yes and 0=no based on participants’ response to a multi-choice question, “Have you had anything to drink in the past two hours?” where they could select “alcohol” among other responses. Consuming alcohol was endorsed 20% of days (2.2% of reports) with an average of 3.5 (SD=3.8) drinks per drinking day.

2.4.5 Recent Smoking

At each report, participants recorded if they smoked in the past 2 hours (yes/no), and the number of cigarettes smoked since the last report. Any smoking in the past 2 hours or since the last report was coded as smoking between reports.

2.4.6 Recent Temptation

At each report, participants responded to an item “did you experience a strong temptation to smoke in the past 30 minutes” (yes/no).

2.4.7 Smoking Outcome

Reports were coded into mutually-exclusive smoking states based on EMA responses: Abstinent reports (i.e., no smoking since the previous report and no strong temptation in the past 30 minutes, 46.1% of reports), Temptation reports (i.e., strong temptation occurred in the past 30 minutes and no smoking since the previous report, 30.8% of reports), and Smoking reports (i.e., smoking occurred since the previous report, 23.1% of reports).

2.4.8 Momentary Impulsiveness

A novel, brief measure of behavioral impulsiveness was administered via EMA using MiniCog software (Cambridge, MA). This was an adapted version of the Conners’ Continuous Performance Test: CPT-II (Conners, 1985, 2004) which measures the ability to inhibit motor responses. Participants were instructed to initiate a 60-66-trial version of the CPT-II task after completing the self-report items. This task involved pressing a key every time a letter appeared on the screen, except when the letter was an “X”. A single letter appeared on the screen for 250 ms, with a variable inter-trial interval of 1, 2, or 4 seconds. Participants could earn $.02 for each correct trial (up to $1.20) and receive performance feedback to enhance motivation. Percent commission error was used to operationalize momentary impulsiveness. Percent commission error has shown good test-retest reliability as a measure of impulsive action (Weafer et al., 2013) and has shown positive relations to smoking status (Schepis et al., 2011) and smoking latency (Bold et al., 2013) in prior research.

To reduce the influence from inaccurate responses due to inattention, reports were excluded if omission errors were greater than 5% (this affected 15.6% of reports). Overall valid completion rate for CPT tasks was nearly 70% once controlling for inattention and missing responses, but there was considerable heterogeneity in response rate by subject, with the average rate only 43.6% (SD=21.4%). Response rates were lower on the CPT-II task than the overall self-report assessments on the EMA, likely due to the fact that device programming required participants to open a separate screen to initiate the CPT-II task after completing the self-report and this extra step may have been burdensome. Analyses with this measure of behavioral impulsiveness were included as secondary aims given the novel administration and low response rates in this sample.

2.5 Data Analysis

A series of multilevel models were tested using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) version 7.01 software to evaluate the independent and interactive effects of smoking risk factors (t0) on outcome up to 8 hours later (t1). Level-one data comprised individual report-level predictors nested within individuals at level two. Continuous predictors were centered around group means to model within-person effects. Reports were included if the time between reports (t0-t1) was at least 30 minutes and no greater than 8 hours, to assess proximal time-lagged effects. The final sample analyzed 4,179 reports from 109 participants (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the final sample (N=109)

| Variable | Value | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (N=109) | Female | 52 (47.7%) |

| Ethnicity (N=107) | Hispanic | 5 (4.6%) |

| Race (N=107) | White | 72 (67.3%) |

| African-American | 25 (23.4%) | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 6 (5.6%) | |

| American Indian | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Other | 3 (2.8%) | |

| Marital Status (N=109) | Married | 41 (37.7%) |

| Never married | 31 (28.4%) | |

| Divorced | 13 (11.9%) | |

| Cohabitating | 10 (9.2%) | |

| Separated | 8 (7.3%) | |

| Widowed | 6 (5.5%) | |

| Education (N=109) | <High school graduate | 1 (0.9%) |

| High school graduate | 27 (24.8%) | |

| Some college | 47 (43.1%) | |

| College degree | 34 (31.2%) | |

| Employment Status (N=109) | Employed for wages | 59 (54.1%) |

| Self-employed | 15 (13.8%) | |

| Unemployed <1 year | 13 (11.9%) | |

| Unemployed >1 year | 8 (7.3 %) | |

| Homemaker | 3 (2.8%) | |

| Student | 11 (10.1%) | |

| Retired | 5 (4.6%) | |

| Disabled | 9 (8.3%) | |

| Household Income (N=107) | <$25,000 | 35 (32.7%) |

| $25,00-$49,999 | 19 (17.8%) | |

| $50,000-$74.999 | 22 (20.6%) | |

| >$75.000 | 31 (28.9%) | |

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (N=109) | 45.0 (12.0) |

| Cigarettes smoked per day (N=109) | 18.6 (6.7) |

| Previous quit attempts (N=109) | 4.3 (9.5) |

| Baseline FTND Score (N=109) | 5.3 (2.0) |

Models had a multinomial outcome distribution with logit link function where Temptation was the reference group to allow efficient, simultaneous comparisons of Abstinent vs. Temptation and Smoking vs. Temptation reports. Results are presented in terms of increased risk indicating the odds of experiencing a strong temptation (vs. abstinent) or smoking (vs. temptation) as a function of within-person levels of affect, urge, context, and impulsiveness at the previous report. We also evaluated negative affect and urge as predictors in smoking vs. abstinent, untempted comparisons to replicate past findings (Shiffman et al., 1996).

All models controlled for smoking status at t0, time between reports, and time since quit day. To verify linearity over smoking state and time, we examined predictor by smoking status, predictor by time between reports, and predictor by time since quit day interactions. Predictors were entered in separate multinominal models to examine main effects. A best-fitting multiple predictor model was created using a backward elimination approach that retained variables in the overall model equation if they were significantly related to either outcome (temptation vs. abstinent or smoking vs. temptation). A priori two-way interactions were examined between level-one predictors in separate models to facilitate model convergence. Lastly, we explored the influence of momentary impulsiveness and examined whether baseline trait impulsiveness moderated relations between momentary impulsiveness and outcome. All models were initially set with a random intercept and random effects to allow regression coefficients to vary across individuals. Predictors were fixed if this permitted model convergence or improved model deviance, measured by a reduction in the −2 log likelihood value (Cohen et al., 2003; Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). Models were run using full-information maximum likelihood estimation.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Model Evaluation

All predictors were normally distributed except momentary impulsiveness, measured by percent commission error (skewness=2.27, SE=0.04; kurtosis=10.18, SE=0.08). The distribution of momentary impulsiveness was improved with a square-root transformation (skewness=1.82, SE=0.04; kurtosis=1.88, SE=0.09). The assumption of linearity in the logit held for all continuously scaled predictors, so no other transformations were necessary. Descriptive statistics for key predictors are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for key study variables by outcome

| Momentary Predictor | Abstinent | Temptation | Smoking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agitationa | 1.84 (0.97) | 2.42 (1.06) | 2.35 (1.12) |

| Distressa | 1.64 (0.88) | 1.94 (0.95) | 2.15 (1.10) |

| Positive Affecta | 3.20 (1.13) | 3.06 (0.96) | 3.10 (1.04) |

| Urgea | 2.09 (1.12) | 3.82 (1.05) | 3.16 (1.31) |

| Impulsivenessb | 0.08 (0.18) | 0.08 (0.18) | 0.08 (0.17) |

| Cigarette Exposurec | 54.90% | 66.90% | 66.30% |

| Alcohol Usec | 1.10% | 2.40% | 3.90% |

Values represent the mean (standard deviation) or frequency of momentary predictors by outcome.

Measured on a scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all/disagree) to 5 (extremely/agree).

Measured by square root percent commission errors on the CPT-II.

Measured Yes/No. Values indicate percentage ‘yes’ response.

Two subjects did not provide sufficient data to be included in HLM models, resulting in n=107 units and df=106 at level-2. These subjects did not differ significantly on demographic, smoking history, or other baseline characteristics of interest (i.e., mood, impulsiveness). A total of 16 subjects reported continuous abstinence post-quit, thus they did not contribute to smoking vs. temptation outcomes but were included to evaluate temptation vs. abstinent outcomes.

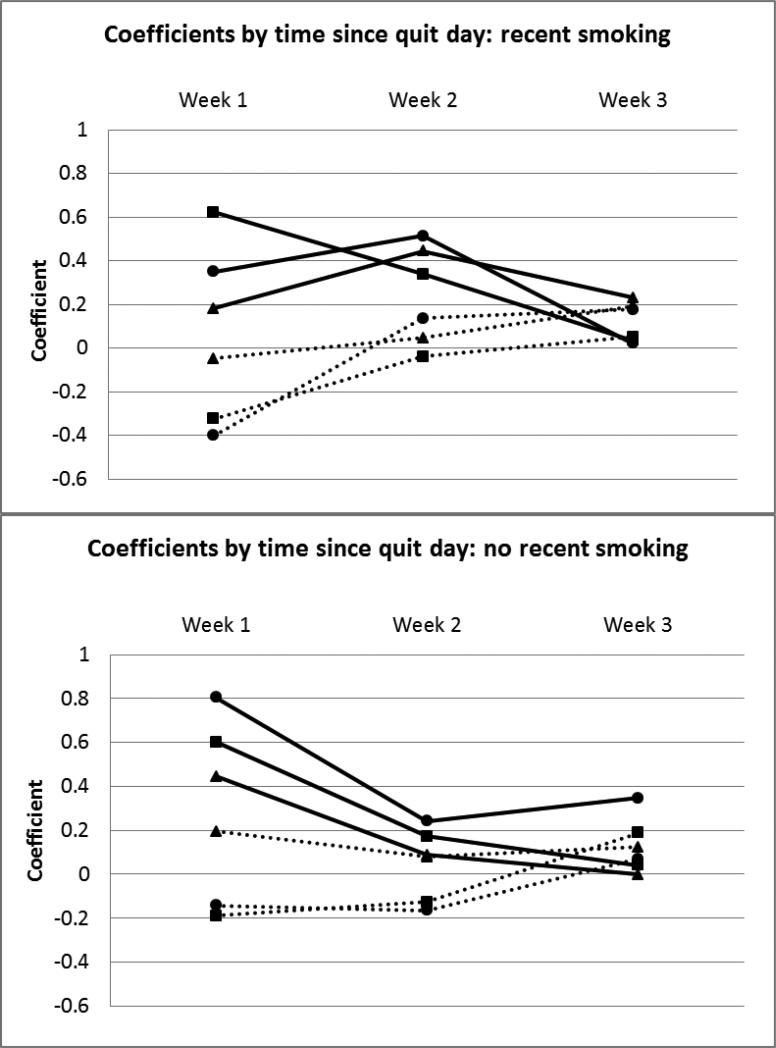

Interactions between predictors and smoking status or time between reports were non-significant. However, time since quit day significantly interacted with several predictors. The effects of agitation, distress, and urge on outcome were non-linear over time. These effects were examined separately in reports without recent smoking (n=3161) and those where recent smoking occurred (n=1018; Figure 1). The effects generally appeared to be strongest in the first week post-quit, except urge and distress had slightly stronger relations to temptation vs. abstinent in week 2 in reports where recent smoking occurred. To account for this non-linear effect over time, a binary time covariate (0=week one post-quit, 1=weeks two-three post-quit) was included in all models which estimated the effects separately across these phases.

Figure 1. Time since quit day interactions with agitation, distress, and urge separated by recent smoking status.

Moderating effects of time since quit day on relations between agitation, distress, and urge and experiencing temptations or smoking separated by whether recent smoking occurred before the report (yes/no). Each line represents the regression coefficient for the predictor at each time point: week 1, week 2, week 3. The coefficients for most of these effects (with the exception of distress and smoking vs. temptation) were most divergent from zero (indicating stronger effects) in the first week post-quit compared to the following one to two weeks. Figure Legend: ■Agitation ▲Distress ●Urge

Solid line=temptation vs. abstinent, Dashed line=smoked vs. temptation.

Table 3 and 4 show the results from single and multiple predictor models, respectively. The multiple predictor model was pruned for non-significant variables and contained a random intercept; random coefficients for agitation, urge, and alcohol use; and fixed coefficients for other predictors. This model fit significantly better than one with these coefficients fixed (χ2=61.83, df=6, p<.001), and setting other predictors to random did not significantly improve model fit.

Table 3.

Single focal predictor main effects for all predictors (t0) on smoking outcome (t1)

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | OR | 95% CI | T-ratio | Approx. df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temptation vs. Abstinent | |||||||

| Agitationa | 0.37 | 0.08 | 1.44 | [1.22-1.72] | 4.19 | 106 | <.001 |

| Distress | 0.26 | 0.07 | 1.30 | [1.12-1.50] | 3.51 | 3848 | <.001 |

| Positive affecta | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.80 | [0.67-0.96] | −2.50 | 106 | 0.014 |

| Urgea | 0.54 | 0.08 | 1.72 | [1.44-2.06] | 6.19 | 106 | <.001 |

| Impulsivenessb | −0.18 | 0.36 | 0.84 | [0.41-1.68] | −0.50 | 2652 | 0.617 |

| Cigarette exposure | 0.12 | 0.14 | 1.13 | [0.85-1.51] | 0.86 | 3848 | 0.392 |

| Alcohola | −0.52 | 0.48 | 0.59 | [0.22-1.55] | −1.08 | 106 | 0.283 |

| Smoking vs. Temptation | |||||||

| Agitationa | −0.18 | 0.10 | 0.83 | [0.68-1.00] | −1.90 | 106 | 0.059 |

| Distress | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1.08 | [0.92-1.26] | 1.02 | 3848 | 0.306 |

| Positive affecta | 0.06 | 0.10 | 1.06 | [0.87-1.30] | 0.64 | 106 | 0.518 |

| Urgea | −0.16 | 0.09 | 0.85 | [0.70-1.03] | −1.66 | 106 | 0.098 |

| Impulsivenessb | 0.11 | 0.42 | 1.12 | [0.48-2.58] | 0.26 | 2652 | 0.789 |

| Cigarette exposure | 0.04 | 0.16 | 1.04 | [0.76-1.42] | 0.27 | 3848 | 0.786 |

| Alcohola | 1.36 | 0.46 | 3.92 | [1.57-9.79] | 2.96 | 106 | 0.004 |

Coefficients represent relations between the predictor and log odds of experiencing a temptation or smoking controlling for recent smoking, time between reports, and time since quit day. SE=Standard Error. OR=Odds Ratio. 95%CI=confidence interval.

Random coefficient. All other predictors were treated as fixed to facilitate model parsimony and convergence.

Momentary impulsiveness data available for N=2930 reports.

Table 4.

Trimmed multiple predictor HLM model of the effects of predictors (t0) on smoking outcome (t1)

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | OR | 95% CI | T-ratio | Approx. df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temptation vs. Abstinent | |||||||

| Intercepta | −0.06 | 0.24 | 0.94 | [0.58-1.54] | −0.22 | 105 | 0.820 |

| Baseline Nicotine Dependencea,b | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.04 | [1.01-1.08] | 2.54 | 105 | 0.013 |

| Recent smoking (prior to t0, 1=yes, 0=no) | −0.19 | 0.16 | 0.82 | [0.60-1.12] | −1.22 | 3206 | 0.223 |

| Time between reports (t0 to t1) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.02 | [0.96-1.08] | 0.79 | 3206 | 0.428 |

| Time since quit day (0=week 1; 1=week 2-3) | −0.77 | 0.12 | 0.46 | [0.36-0.58] | −6.59 | 3206 | <.001 |

| Agitationa | 0.20 | 0.09 | 1.22 | [1.02-1.48] | 2.18 | 106 | 0.031 |

| Distress | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.95 | [0.78-1.14] | −0.52 | 3206 | 0.600 |

| Urgea | 0.48 | 0.08 | 1.60 | [1.35-1.92] | 5.42 | 106 | <.001 |

| Alcohola | −0.46 | 0.52 | 0.62 | [0.22-1.74] | −0.90 | 106 | 0.367 |

| Smoking vs. Temptation | |||||||

| Intercepta | −0.94 | 0.23 | 0.39 | [0.24-0.62] | −4.04 | 105 | <.001 |

| Baseline Nicotine Dependencea,b | −0.004 | 0.02 | 1.00 | [0.96-1.03] | −0.21 | 105 | 0.834 |

| Recent smoking (prior to t0, 1=yes, 0=no) | 1.24 | 0.14 | 3.46 | [2.58-4.63] | 8.37 | 3206 | <.001 |

| Time between reports (t0 to t1) | 0.14 | 0.03 | 1.15 | [1.08-1.23] | 4.18 | 3206 | <.001 |

| Time since quit day (0=week 1; 1=week 2-3) | 0.56 | 0.13 | 1.75 | [1.35-2.28] | 4.22 | 3206 | <.001 |

| Agitationa | −0.28 | 0.10 | 0.75 | [0.60-0.92] | −2.70 | 106 | 0.008 |

| Distress | 0.26 | 0.10 | 1.30 | [1.06-1.60] | 2.58 | 3206 | 0.010 |

| Urgea | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.87 | [0.72-1.06] | −1.40 | 106 | 0.164 |

| Alcohola | 1.31 | 0.49 | 3.71 | [1.40-9.89] | 2.66 | 106 | 0.009 |

Multiple predictor HLM model including level one and level two covariates. Non-significant variables were pruned from the model. SE=Standard Error. OR=Odds Ratio. 95%CI=confidence interval.

Random coefficient. All other predictors were treated as fixed to facilitate model parsimony and convergence.

Baseline nicotine dependence measured by the total score on the WISDM-68. Similar results are obtained using the FTND total score (temptation vs. abstinent: coefficient=0.22, SE=0.09, OR=1.24, 95% CI [1.02-1.50], t(105)=2.28, p=.02; smoking vs. temptation: coefficient=0.02, SE=0.09, OR=1.02, 95% CI [0.85-1.22], t(105)=0.24, p=.80).

3.2 Temptation vs. Abstinent

Models estimated the odds of experiencing a temptation (vs. being abstinent and untempted; Table 3 and 4 top panel). Results indicated greater odds of temptation in the first week after the quit-day. Distress was positively associated with temptations while positive affect protected against temptations in single predictor, but not multiple predictor, analyses. Results from the multiple predictor model indicated momentary agitation and urge were positively related to later temptation risk. Baseline nicotine dependence was the only significant level-two predictor, indicating smokers with higher nicotine dependence were more likely to experience temptations post-quit. The same pattern of results was seen whether using the total WISDM-68 or FTND score to operationalize dependence. The same pattern of results was seen when controlling for temptation at t0 or reported nicotine lozenge use between t0 and t1. Lozenge use between t0 and t1 was significantly positively related to experiencing a temptation (vs. abstinent) at t1 (B=0.38, SE=0.15, t(3033)=2.50, p=.01).

Interactions between level-one predictors were examined and two primary findings were noted. Urge and agitation had a significant synergistic relationship (B=0.12, SE=0.06, t(3844)=1.98, p=.047). Urge was more strongly related to later temptation in agitated states compared to times when agitation was low (Figure 2a). Additionally, cigarette exposure significantly moderated the relation between urge and experiencing temptations (B=0.32, SE=0.12, t(3844)=2.72, p=.006) (Figure 2b). Specifically, smokers were much more likely to report a strong temptation following times of heightened urge if cigarettes were available (OR=19.09) than if cigarettes were not available (OR=4.76). In secondary analyses, the interaction between impulsiveness and positive affect was significant (B=0.89, SE=0.44, t(2648)=2.00, p=.046). Positive affect was more protective against temptations in states of low momentary impulsiveness compared to high momentary impulsiveness (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a-c. Level-one interactions predicting log odds of temptation vs. abstinence.

Interaction effects of urge x agitation, urge x cigarette exposure, and positive affect x impulsiveness on the log odds of experiencing a temptation. To plot these effects for the continuously scaled constructs, log odds were calculated from low (1 SD below mean), mid (mean), and high (1 SD above mean) range values. Impulsiveness values reflect square-root percent commission errors on a momentary behavioral disinhibition task. Log odds can be exponentiated to derive odds ratios of experiencing a temptation (ex). Figure Legend: 2a. Solid line=high agitation. Dashed line=low agitation. 2b. Solid line=easy access to cigarettes. Dashed line=no cigarettes available. 2c. Solid line=high impulsiveness. Dashed line=low impulsiveness.

3.3 Smoking vs. Temptation

Multinomial models also estimated the odds of smoking (vs. experiencing a temptation without smoking; Table 3 and 4 bottom panel). The odds of smoking were greater 2-3 weeks post-quit compared to the first week after the target quit-day. Additionally, smoking (vs. temptation) was more likely when smoking had occurred at the previous report and when more time lapsed between predictor and outcome reports (t0-t1). Consistent with our hypotheses, higher distress and recent alcohol consumption predicted greater odds of smoking at the next report. Contrary to expectations, higher agitation predicted lower odds of smoking, or increased odds of resisting a temptation without smoking. In models comparing smoking vs. abstinent, untempted events, smoking was predicted by urge (B=0.33, SE=0.08, t(106)=3.97, p<.001) and distress (B=0.22, SE=0.10, t(3206)=2.15, p=.031), but not agitation (B=−0.08, SE=0.10, t(106)=−0.82, p=.411).

The pattern of results was the same when removing n=11 participants who continued smoking post-lapse and did not provide additional temptation or abstinent reports. The pattern of results was unchanged when controlling for nicotine lozenge use between t0 and t1. Lozenge use was significantly protective against smoking (vs. experiencing a temptation) (B=−1.10, SE=0.16, t(3033)=-6.65, p<.001).

No interactions between level-one predictors were significant. Secondary analyses examining the influence of momentary impulsiveness indicated a non-significant interaction between impulsiveness and context. Specifically, momentary impulsiveness was marginally more likely to lead to smoking if alcohol was recently consumed than if alcohol was not consumed (B=5.42, SE=2.83, t(2648)=1.91, p=.056).

Although momentary impulsiveness did not significantly relate to smoking in secondary analyses, baseline impulsiveness was a significant moderator of this relationship (B=0.12, SE=0.04, t(2018)=2.78, p=.005). Within-person momentary impulsiveness was more strongly related to smoking for individuals with higher (vs. lower) self-reported trait impulsiveness measured by the BIS (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cross-level interaction between state and trait impulsiveness predicting log odds of smoking vs. temptation.

Interaction between state impulsiveness (measured by momentary behavioral disinhibition) x trait impulsiveness (measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, BIS-11). To plot these effects, log odds were calculated from low (1 SD below mean), mid (mean), and high (1 SD above mean) range values for the momentary behavioral disinhibition task. Log odds can be exponentiated to derive odds ratio of smoking (ex). Figure Legend: Solid line=high trait impulsiveness measured by BIS. Dashed line=low trait impulsiveness measured by BIS.

4. DISCUSSION

The current project used time-lagged multinomial hierarchical linear modeling to evaluate the independent and interactive effects of relapse risk factors on experiencing strong temptations and smoking up to 8 hours later in smokers trying to quit. The results suggest the determinants of temptations and smoking differ, and that both are influenced by combinations of risk factors above and beyond their main effects. Studying more complex relationships between risk factors may provide new information about relapse mechanisms.

Several risk factors were significantly related to experiencing a strong temptation (vs. being abstinent and untempted) including greater nicotine dependence and higher within-person agitation and urge at the previous report. Although it is not surprising that urge ratings predicted later temptation, these measures were assessed in distinct ways and this relation was significant even when controlling for experiencing a strong temptation at the previous report. Additionally, the modest odds ratio suggests there may be conceptual distinctions between urge and temptation (as supported by previous work, e.g., Shiffman et al., 1996). Additionally, distress and positive affect were univariate predictors of temptation, but were non-significant in the multiple predictor model. There were notable interactions between urge, affect, and context. Specifically, urge and agitation had synergistic effects on temptation risk, and although there was not a main effect of cigarette exposure, urge was more strongly related to later temptations when cigarettes were available. Secondary analyses suggested an interaction between impulsiveness and affect, such that states of high impulsiveness reduced the protective effect of positive affect on temptation risk.

In models predicting smoking (vs. resisting a temptation without smoking), higher momentary distress predicted significantly greater smoking risk while higher agitation unexpectedly predicted resisting temptations without smoking. These effects emerged as significant in the multivariate model, but not the single predictor models. Agitation and distress appear to tap different smoking motivation processes and their independent influence may be more pronounced once other variance is accounted for. Additionally, recent alcohol use significantly predicted smoking versus resisting a temptation. Secondary analyses revealed that impulsiveness was more strongly related to later smoking when alcohol was recently consumed, and those with high baseline self-reported impulsiveness were at greater risk.

Interestingly, the effect of several of these predictors was strongest for the first week post-quit compared to the following two weeks. Additionally, smokers were less likely to experience temptations and more likely to smoke over time. Taken together, our results suggest smokers reach a steady state around the first week of quitting which coincides with research showing rapid returns to smoking after quitting (Baker et al., 2007). In the current study, smokers were 3.5 times more likely to smoke than resist temptations if they recently smoked (vs. abstained). These findings may reflect the abstinence violation effect (Marlatt and Gordon, 1985), suggesting smokers gave up on the quitting process after initial failure. Thus, there may be a critical post-quit window where it is important to achieve initial success resisting temptations or receive support to rebound from initial failure.

All results are in the context of standard care with counseling and nicotine lozenge. Smokers experienced strong temptation and smoking episodes despite this treatment, suggesting our approaches may need to be strengthened. Counseling smokers to cope with different facets of negative affect or to avoid high-risk situations such as cigarette and alcohol exposure may be critical to cessation success. Also, smokers with greater nicotine dependence or trait impulsiveness may be particularly at risk and require additional interventions to quit.

There are limitations to the current study which should be considered. First, the results are subject to reporting bias due to missing responses to EMA prompts. Additionally, the optimal time-frame to capture the mechanisms driving temptations and smoking is unknown. We attempted to control for lag between predictor and outcome by limiting the time between reports, yet longer time between reports remained a significant predictor of smoking. More frequent EMA assessment or use of complementary methods (i.e., laboratory studies) may be needed to identify the most proximal lapse mechanisms. We were unable to examine differences between lapse events for those who lapsed once and recovered abstinence compared to those who lapsed multiple times, given the infrequent occurrence of single lapses in our sample (n=17). Future work may benefit from identifying differences in the characteristics of single versus chronic lapses. In addition, there is limited information on the psychometric properties of brief momentary measures. There may be particular challenges to assessing in-vivo disinhibition including reduced attention or compliance with the task, so replication and evaluation of construct validity using complementary measures of impulsiveness will be important in future work. Furthermore, we had limited power to detect interactions between occasion- and person-level variables. The influence of other baseline and personality variables should be examined in future studies.

The current study provides new information about key risk factors for temptations and smoking behavior after quitting. These risk factors were detectable in advance of temptations and smoking, suggesting potential targets for near- or real-time interventions. Additionally, this study is among the first to document ways real-time measures of affect, urge, and context combined to modify short-term risk for temptations and smoking. Examining complex models of smoking risk may be a critical step in improving our understanding of lapse processes and informing intervention development.

Highlights.

Modeled within-person risk factors for temptations and lapses in adult smokers.

Used time-lagged hierarchical linear modeling to identify risk prior to outcome.

Independent and interactive effects of urge, affect, impulsiveness, and context.

Antecedents of temptations and lapses differ, suggesting separate interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Rutgers University Smoking Cessation Laboratory and the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research for their assistance with this project.

Role of Funding Source: This research was supported by Award Number RC1DA028129 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: All authors contributed significantly to the design, implementation, analysis, and reporting of this research. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. McCarthy has received nicotine replacement therapy at discounted rates from GlaxoSmithKline in the past. GlaxoSmithKline played no role in the current study. None of the other authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Baker TB, Mermelstein R, Collins LM, Piper ME, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Christiansen BA, Schlam TR, Cook JW, Fiore MC. New methods for tobacco dependence treatment research. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011;41:192–207. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Morse E, Sherman JE. The motivation to use drugs: a psychobiological analysis of urges. In: Rivers PC, editor. The Nebraska Symposium On Motivation: Alcohol And Addictive Behavior. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 1987. pp. 257–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, Colby S, Conti D, Giovino GA, Hatsukami, Hyland A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Niaura R, Perkins KA, Toll BA. Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Reearch Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence, 2007. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 9:S555–S570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol. Rev. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bold KW, Yoon H, Chapman GB, McCarthy DE. Factors predicting smoking in a laboratory-based smoking-choice task. Exp. Clin. Psychopharm. 2013;21:133–143. doi: 10.1037/a0031559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Quitting Smoking Among Adults-United States, 2001-2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses-United States, 2000-2004. MMWR. 2008;57:1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis For The Behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test II (CPTII) for Windows Technical Guide and Software Manual. Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. The computerized continuous performance test. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1985;21:891–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004;43:245–265. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Cook J, McChargue D, Myers M, Spring B. Cue-elicited negative affect in impulsive smokers. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008;22:249–256. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Santarcangelo M, Sumnall H, Goudie A, Cole J. Delay discounting and the behavioral economics of cigarette purchases in smokers: the effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacol. 2006;186:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Borland R, Hyland A, McKee SA, Thompson ME, Cummings KM. Alcohol consumption and quitting smoking in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Drug Alcohol. Dep. 2009;100:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CY, Businelle MS, Aigner CJ, McClure JB, Cofta-Woerpel L, Cinciripini PM, Wetter DW. Individual and combined effects of multiple high-risk triggers on postcessation smoking urge and lapse. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16:569–575. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies In The Treatment Of Addictive Behaviors. Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DE, Minami H, Yeh VM, Bold KW. An experimental investigation of reactivity to ecological momentary assessment frequency among adults trying to quit smoking. Addiction. 2015;110:1549–1560. doi: 10.1111/add.12996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Lawrence DL, Jorenby DE, Shiffman S, Baker TB. Psychological mediators of bupropion sustained-release treatment for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2008;103:1521–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami H, Yeh VM, Bold KW, Chapman GB, McCarthy DE. Relations among affect, abstinence motivation and confidence, and daily smoking lapse risk. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014;28:376–388. doi: 10.1037/a0034445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Effects of short-term nicotine deprivation on decision-making: delay, uncertainty, and effort discounting. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:819–828. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331296002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995;6:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman EB, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. A multiple motives approach to tobacco dependence: the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68). J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:139–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications And Data Analysis Methods. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, McFetridge A, Chaplin TM, Sinha R, Krishnan-Sarin S. A pilot examination of stress-related changes in impulsivity and risk taking as related to smoking status and cessation outcome in adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011;13:611–615. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol. Assess. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Hickcox M, Paton SM. Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents assessed by ecological momentary assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: within subjects analysis of real-time reports. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996;64:366–379. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Ann. Behav. Med. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Kahler CW, Leventhal AM, Abrantes AM, Lloyd-Richardson E, Niaura R, Brown RA. Impact of bupropion and cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression on positive affect, negative affect, and urges to smoke during cessation treatment. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009;11:1142–1153. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug use behavior: role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychol. Rev. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Warthen MW, Goedeker KC. The functional significance of craving in nicotine dependence. In: Bevins R, Caggiula A, editors. The Motivational Impact of Nicotine and its Role in Tobacco Use. Springer Science + Business Media; New York: 2009. pp. 171–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences Of Smoking: A Report Of The Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Baggott MJ, de Wit H. Test-retest reliability of behavioral measures of impulsive choice, impulsive action, and inattention. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:475–481. doi: 10.1037/a0033659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch SK, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Development and validation of the Wisconsin smoking withdrawal scale. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:354–361. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: Factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict. Behav. 2009;34:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]