Abstract

Microfluidic based blood plasma extraction is a fundamental necessity that will facilitate many future lab-on-a-chip based point-of-care diagnostic systems. However, current approaches for providing this analyte are hampered by the requirement to provide external pumping or dilution of blood, which result in low effective yield, lower concentration of target constituents, and complicated functionality. This paper presents a capillary-driven, dielectrophoresis-enabled microfluidic system capable of separating and extracting cell-free plasma from small amounts of whole human blood. This process takes place directly on-chip, and without the requirement of dilution, thus eliminating the prerequisite of pre-processed blood samples and external liquid handling systems. The microfluidic chip takes advantage of a capillary pump for driving whole blood through the main channel and a cross flow filtration system for extracting plasma from whole blood. This filter is actively unblocked through negative dielectrophoresis forces, dramatically enhancing the volume of extracted plasma. Experiments using whole human blood yield volumes of around 180 nl of cell-free, undiluted plasma. We believe that implementation of various integrated biosensing techniques into this plasma extraction system could enable multiplexed detection of various biomarkers.

I. INTRODUCTION

Various biochemical analysis methods require blood plasma as an analyte. For most existing diagnostic assays, this plasma is obtained through centrifuge of relatively large volumes of blood.1 This method is not practical for mobile point-of-care devices; therefore, an effective miniaturised method of plasma extraction is required with sufficient yield to enable portable lab-on-a-chip based point-of-care devices.

Various methods of plasma extraction have been developed for use in lab-on-a-chip applications.1–4 These techniques can be divided into two primary categories, those that incorporate the use of a filter and those that use some other means of blood cell separation.

Filter based systems use some form of mechanical filtration to physically separate blood cells from plasma. Isolation and collection of plasma has been accomplished using planar micro-filters,5,6 as well as cross flow filtration techniques.7–10 Various dead end filtration techniques have also been investigated,11 and more recently, methods of combining dead end filtration with sedimentation have been investigated.12 The filter based systems have several drawbacks, primarily due to the fact that they can only operate for a short time before the filter structures become overwhelmed by blood cells and become blocked. Some filter based systems improve their performance through the use of diluted blood,7,8 or through the use of pumps to introduce a pressure gradient across the filter structure.8,10,12–14 These solutions are undesirable, as they require additional liquid handling steps and pumps, making the system less suitable for point-of-care applications. Additionally, dilution of whole blood effectively depletes biomarkers present in blood plasma, some of these biomarkers are rare in whole blood, and thus the dilution process can make them even more difficult, or sometimes impossible to detect.1,15 Filter based systems that are capable of operating with whole blood, and utilise capillary forces alone, generally have an extracted plasma volume too low for many biochemical analysis methods.

Alternatively, non-filter based systems employ other methods to separate blood cells from plasma. Acoustic plasmaphoresis,16 dielectrophoresis,17 sedimentation,12,18 asymmetric capillary force fractionation,19 gravitational sedimentation delamination,14 separation based on the Zweifach-Fung effect,20 and combination of multiple hydrodynamic effects21 are some examples of established non-filter based systems. Sedimentation and asymmetric capillary force fractionation are both capable of extracting modest volumes of plasma quickly;12,18,19 however, due to their design, they reach a certain point at which the separation method is overwhelmed by blood cell volume. Gravitational sedimentation delamination is a constant flow process,14 but works only with diluted blood pumped by external support equipment, while Zweifach-Fung effect based approaches have similar drawbacks.20 Acoustic plasmaphoresis and the combination of multiple hydrodynamic effects16,21 yield promising results with whole blood; however, these approaches cannot provide completely cell-free plasma, and both require complex external fluid handling systems. More recently, blood plasma has been extracted from diluted blood in a cross flow filter based device employing an active reversible electro-osmotic flow based unblocking technique.22 This technique enables active pulsatile unblocking of the filter entrance and significantly improves efficiency of the cross flow filter.

It is clear from these findings that a plasma extraction system is required that can work effectively with whole blood, as part of a capillary flow system that can extract significantly more plasma than existing capillary based systems. Such a system would enable a multitude of on-chip biochemical analysis processes that require more plasma than is available using established systems, to be integrated within lab-on-a-chip platforms. This would effectively increase the diagnostic capabilities of point-of-care systems and enable access to advanced medical diagnosis capabilities to areas that would otherwise be cost prohibitive.

Dielectrophoresis is a well-established method for manipulating polarisable particles within a liquid medium.23–26 Dielectrophoresis has found numerous applications for separating biological particles within microfluidic systems27 and has been shown to work effectively for the sorting and processing of blood cells for various pre-treated sample analysis applications.28–35 While these applications demonstrate the efficacy of dielectrophoresis for manipulation and analysis of blood cells, these approaches require sample pre-processing and are best suited to applications either downstream of an on-chip sample preparation module or within a system reliant on external sample preparation systems. Dielectrophoresis has also shown promise as a means of sample preparation and has been used to extract plasma from blood in a capillary-based system,17,36 and more recently in a continuous flow system requiring an external pump;37 however, these systems could only process diluted blood, and as such, the extracted volumes are low. Recently, dielectrophoresis has been shown to effectively separate plasma from undiluted blood.36,38,39 These systems demonstrate a significant improvement in the field and work towards eliminating the issue of biomarker rarefication. A recent capillary driven dielectrophoresis based system38 is shown to extract significant volumes of plasma from whole blood. This system operates in a manner similar to the aforementioned asymmetric capillary force fractionation system,19 retarding the flow of red blood cells in a capillary channel while allowing the plasma to flow unabated. However, like the demonstrated asymmetric capillary force fractionation system,19 this system cannot provide pure cell-free plasma. Another recent system utilises enhanced dielectrophoresis combined with antibody-coated beads to purify blood plasma.39 This system, while currently a proof-of-concept and not yet shown to work with whole blood, promises to also produce a significant amount of plasma; however, it requires external fluid handling, a fairly complex fabrication, and could apply significant thermal stress to the sample.

In this paper, we present an enhanced method of plasma extraction, capable of extracting plasma from whole human blood, with the aim of fulfilling the requirements of a point-of-care lab-on-a-chip extraction system. This extraction approach builds on concepts presented in the literature, utilising a capillary driven cross flow filter demonstrated in Ref. 7, complemented by an active unblocking element enabled by repulsive dielectrophoretic (DEP) forces presented in Refs. 17. A proof-of-concept prototype system is fabricated to demonstrate the viability of this approach and characterise its performance. The extraction approach is shown to be effective with whole human blood, to function as part of a capillary driven system, and is able to produce a modest yield of undiluted cell-free plasma. While extraction efficiency for this proof-of-concept system is low, the volume of cell-free undiluted blood plasma extracted is sufficient to enable various biomarker detection techniques.40–43 These factors, combined with the automated nature of capillary-based systems, make this approach ideal for point-of-care biochemical analysis.

II. PRINCIPLES OF PLASMA EXTRACTION SYSTEM

A. Prototype design

Fig. 1(a) shows a conceptual representation of the functional plasma extraction system. The system consists of a borosilicate glass slide base with a thickness of 2 mm. Placed over this glass substrate is a block consisting of PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane, DowCorning Corp., Sylgard 184). This block is patterned with the required microfluidic structures, including a sample input port, primary channel, cross flow filter, and capillary pumps.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual representation of the blood plasma extraction system. (a) Centre is an isometric image showing system components in exaggerated scale. Whole blood is introduced to a biopsy punched inlet reservoir shown on the right, and flows through the primary channel past the cross flow filter entrance, where plasma is extracted through a ∼1.2 μm deep channel supported by a repetitive post structure. Negative DEP forces actively unblock the entrance to this filter, as shown inset (b). The height of the cross flow filter structure prevents blood cells from infiltrating the plasma collection capillary pump, which draws separated plasma and acts as a storage reservoir. Phase transition of plasma from the 1.2 μm filter to 25 μm plasma collection capillary pump is enabled through the use of tapered wedge shaped capillary transition enhancer structures, as shown in inset (c). Inset (c′) illustrates the path taken by the blood plasma as a cross sectional view, highlighting the DEP effect with red arrows. Processed blood continues to flow past the cross flow filter and is collected in the waste extraction capillary pump, inset (d). Note that this figure is not to scale and DEP repulsion is exaggerated to demonstrate effect.

Patterned onto the glass substrate are DEP electrodes; these consist of 25 nm titanium, which acts as an adhesion layer for the 250 nm conductive gold electrodes. The design of these electrodes is based on that used in Ref. 17 to separate plasma from highly diluted blood. These electrodes have been proven to work effectively with diluted blood samples, and as such are used in this system as a proof-of-concept with undiluted blood. Processing of whole blood is made possible by a combination of the DEP separation technique with a hydrodynamic filter based separation system based on that presented in Ref. 7. The electrodes can be seen in Fig. 1(b).

The structures patterned into PDMS consist of a sample input port, formed by a biopsy punched hole 4 mm in diameter, intersecting a 500 μm wide primary channel with a depth of 25 μm. This primary channel runs from sample input, past a cross flow filter structure to a waste extraction capillary pump. The capillary pump consists of an array of parallel 100 μm wide, 25 μm deep channels, as shown in Fig. 1(d), and is used to draw sample past the filter, as well as acting as a storage area for depleted blood. Another similarly designed pump is located in the plasma collection area to draw plasma through the cross flow filter and act as a storage reservoir, shown in Fig. 1(c). This filter structure prevents inadvertent infiltration of blood cells from the exceedingly dense whole blood (40%–50% haematocrit) during initial filling of the system as well as during operation, while actively cleansing the filter entrance of depleted blood and providing a constant supply of fresh sample. The cross flow filter is based on the one outlined in Ref. 7, where this filter was used to extract plasma from diluted blood, while also demonstrating potential to extract plasma from whole blood.

The height of the filter is set to 1.2 μm. This is to restrict the infiltration of red blood cells (with an average thickness of 1.7–2.2 μm (Ref. 44)) to cross flow filter in the absence of DEP force, which is the case during the initial loading of the primary channel with blood. This also restricts the penetration of platelets (with a maximum diameter of 2–3 μm (Ref. 45)) into the filter in the presence of DEP force. More importantly, by increasing the height of the filter channel, although the red blood cells might be effectively repelled from microelectrode tips, they might penetrate into the filter via the regions of lower DEP force between the neighbouring microelectrodes. In this case, the performance of the system will heavily depend on various operational parameters of the system, including the flow rate of blood through the primary channel, haematocrit, the alignment of microelectrodes with respect to the cross flow filter entrance, as well as surface wetting properties of the PDMS and glass that may vary depending on ambient humidity and individual blood parameters.

The filter structure is supported by a poststructure patterned in a repetitive array; this poststructure prevents the narrow filter gap from collapsing and it occupies approximately 47% of the filter channel, as shown in Fig. 1(b) and a cross sectional view in Fig. 1(c). Due to the high flow resistance of the narrow filter pathway, the cross flow filter structure is kept to a minimal length. The extreme transition in channel depth from the 1.2 μm deep filter channel to the 25 μm deep plasma extraction capillary pump is made possible through implementation of wedge shaped capillary transition enhancer structures, as shown in Fig. 1(c). These structures function in a manner similar to the structures shown in Ref. 46 and allow for the coupling of a shallow microfluidic structure with high flow resistance and high capillary pressure to a deeper structure with comparatively negligible flow resistance and low capillary pressure, overcoming the sharp drop in pressure which would ordinarily terminate capillary flow. The cross flow filter structures are also shown as a cross sectional view in Fig. 1(c′).

B. Principles of capillary pump operation

Capillary forces are the primary driving forces used to drive the fluid flow in this system. The use of capillary forces enables cheap and easy mass producible stand-alone units that do not require additional supporting fluid handling equipment, thus resulting in a system suitable for low cost, disposable point-of-care analysis.

The flow rate in a capillary system can be controlled through the careful design and application of capillary pump structures. Capillary flow occurs due to cohesion and surface tension of the fluid in question, as well as adhesion of fluid to the solid surfaces of the capillary. The capillary flow rate can be adjusted using various configurations of capillary pump, utilising various flow resistance and adhesion properties.46–48 Further details outlining principles of capillary pump operation are provided in supplementary material S1.49

1. Waste extraction capillary pump

Due to the branching nature of the waste extraction capillary pump, the parallel channels fill sequentially as the meniscus in the primary channel advances along the entrance of the pump. Although the flow rate in these channels decreases exponentially with the advancement of the meniscus along the channel length, the flow rate in the primary channel past the cross flow filter is maintained at a relatively constant rate by the sequential opening of additional waste pump channels. Further details regarding the performance of the waste extraction capillary pump is given in supplementary material S2.49

2. Plasma extraction capillary pump

The plasma extraction capillary pump has a flow rate dominated by the resistance of the preceding cross flow filter. With a depth of 1.2 μm, and with a complex and narrow geometry, the resistance of this filter is significantly larger than that of the capillary pump. The flow rate is initially high on entry to the cross flow filter structure, however, drops off quickly across the 200 μm filter length. A sharp drop in capillary pressure due to a sudden increase in the channel cross section occurs at the transition to the 25 μm deep plasma extraction capillary pump. Ordinarily, this sudden drop in capillary pressure terminates flow; however, this transition is smoothed through the use of wedge shaped capillary transition enhancer structures. These structures function in a manner similar to structures used in Ref. 46 and consist of tapered wedge shaped channels which apply graduated capillary pressure from a high point at the narrow tip (∼7 μm), located within the filter structure, to match that of the pump channels (100 μm), thus allowing plasma that has passed through the filter to transition to the pump structure. Further details regarding the design of the plasma extraction capillary pump is given in supplementary Fig. S1.49

C. Principles of dielectrophoresis

The filtering process outlined in Section II is maintained by an active unblocking mechanism through the application of negative dielectrophoresis. Dielectrophoresis refers to the induced motion of polarisable particles, suspended in a medium, when subjected to a non-uniform electric field, and is commonly used as a means of manipulating bio-particles, including cells within microfluidic systems.23–27

When a polarisable particle such as a cell is exposed to an electric field, electrical charges are induced on the cell/medium interface. The induced charges make up dipoles aligned parallel to the applied field. When a uniform field is applied, each half of the dipole experiences equal Coulombic forces, resulting in equal and cancelling forces applied to the cell. Conversely, in a non-uniform electric field, the applied Coulombic forces are unequal, resulting in a net force imposed on the cell. The cell can be attracted toward or repelled from regions of strong electric field, depending on their relative polarisability, with reference to the surrounding medium.50 Assuming that cells have a spherical shape, they experience a DEP force which can be expressed as follows:50

| (1) |

where εm is the permittivity of the medium, r is the radius of the cell, Erms is the root-mean-square (RMS) value of electric field, and Re(fCM) is the real part of the Clausius–Mossotti factor. The Re(fCM) determines whether the induced force applied is repulsive (negative DEP) or attractive (positive DEP) with respect to regions of strong electric field, and for a spherical cell can be defined as follows:

| (2) |

where and are the complex permittivities of the cell and medium, respectively, which is given by , where is the real permittivity, is the electric conductivity, and ω is the angular frequency of the AC electric field.17,24,35

Red blood cells have a more complicated structure, consisting of a cytoplasmic core encapsulated within a plasma membrane, and their Re(fCM) is often calculated using the single-shell spherical model.50 In this model, the equivalent complex permittivity of cell, , is calculated by taking into account the dielectric properties and dimensions of both cytoplasm and plasma membrane. The is then inserted into Equation (2) to predict the Re(fCM) of the cell, as detailed in supplementary material S4.49 The geometrical and dielectric properties of red blood cells are given in supplementary material Table S2.27,49,51

Using these parameters, the Re(fCM) of red blood cells is calculated in different electrical conductivities of the blood plasma corresponding to different dilution ratios, as shown in Fig. 2. It can be seen that the red blood cells exhibit a negative DEP response when the conductivity of the blood plasma (σplasma) is higher than 0.3 S/m across the entire frequency range of 1 kHz to 100 MHz. For the case of undiluted blood, which is used in our work, σplasma = 1.2 S/m, and the strongest negative DEP response is achieved at frequencies lower than 100 kHz. In our work, the frequency of the applied signal is set to 1 MHz. While the negative DEP response of cells is slightly weaker when compared with 100 kHz, the selected frequency of 100 MHz ensures that thermal stress applied to the blood due to the Joule heating effect is minimised.50

FIG. 2.

(a) The real component of the Clausius–Mossotti factor–Re(fCM) calculated for human red blood cells, plotted for various dilutions of blood plasma vs applied AC excitation frequency. The red blood cells exhibit a strong negative DEP response at σplasma = 1.2 S/m and 1 MHz, repelling them from the cross flow filter entrance. Simulated electric field (b) and applied DEP force (c). These simulations are representative of a segment of the cross flow filter/primary channel interface, as shown in Figs. 1(b) and 1(c′). The dotted line indicates the entrance of the cross flow filter structure. The area within this filter, to the left of the line has a depth of 1.2 μm, while the primary channel to the right of this line has a depth of 25 μm. (b) The distribution of the electric field generated by the electrodes when energised at 8 V, peak to peak. (c) The gradient of electric field square, which is proportional to the applied DEP force.

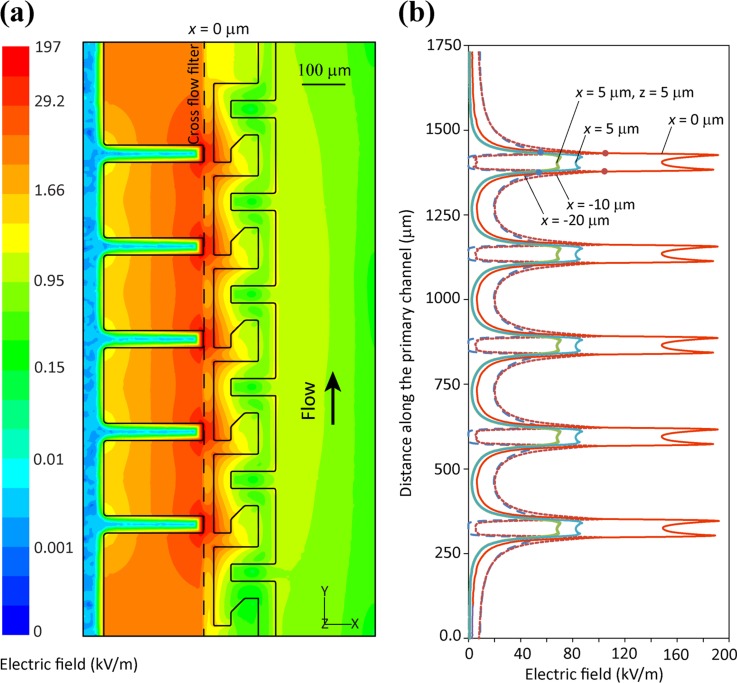

Fig. 2(b) shows the distribution of electric field exerted by the electrodes, when energising electrodes at 8 V peak-to-peak obtained by numerical simulations, as detailed in supplementary material S5.49 In our simulations, the depth of the main channel is 25 μm while the depth of the filter structure channel is 1.2 μm. Simulations indicate that electric field reaches a peak of 197 kV/m at the tip of left-hand-side electrodes while reduces to ∼42 kV/m along the entrance of the cross flow filter. Fig. 2(c) shows the gradient of electric field square, , which is proportional to the DEP force exerted on blood cells. Simulations indicate that reaches a peak of 8.2 × 1014 V2/m3 at the tip of left-hand-side electrodes, while it reduces to ∼8.6 × 1013 V2/m3 along the entrance of the cross flow filter. Our simulations indicate that the change of depth at the entrance of the cross flow filter significantly modifies the distribution of electric field and DEP forces within the channel, enhancing the repulsive forces applied through dielectrophoresis, as explored in supplementary Fig. S2.49 This increase in repulsive DEP force enhances the active clearing efficiency of the system, reducing flow resistance at the cross flow filter entrance and enhancing plasma extraction. This enhancing effect can however only be demonstrated so long as the electrode tips are accurately aligned along the entrance of the filter, identifying electrode/filter alignment as a critical factor in the overall system performance.

The generation of strong electric fields can lyse the blood cells while passing through the primary channel or damage the precious biomarkers when entering the cross flow filter structure. However, the extent of damage depends on the magnitude of electric field and the amount of time that bioparticles are exposed to strong electric field. Despite generation of strong electric fields with a maximum magnitude of 197 kV/m that is strongly localised at the tip of microelectrodes, electric field decays exponentially when getting far from microelectrodes, as shown in Fig. 3(a). To further analyse this matter, we compare the variation of electric field along five arbitrary lines parallel to the entrance of the cross flow filter structure, as shown in Fig. 3(b). These lines are located at x = 0 μm (at the entrance of the cross flow filter), x = 5 μm (further into the primary channel with the first line lying along the glass slide and the second one lying at a height of z = 5 μm), and x = −20 μm and −10 μm (further into the plasma extraction channels). The electric field follows a similar trend along these lines, with peak values observed close to the tips of microelectrodes, which is extended over a span of ∼50 μm. Our simulations reveal a maximum electric field of 197 kV/m at x = 0 μm, which entering the primary channel reduces to 87 kV/m at x = 5 μm and further reduces to 70 kV/m at z = 5 μm. Similarly, entering the plasma extraction channels electric field reduces to 105 kV/m at x = −10 μm and further reduces to 55 kV/m at x = −20 μm.

FIG. 3.

(a) Distribution of electric field across the surface of glass slide and (b) the variations of electric field along five arbitrary lines parallel to the entrance of the cross flow filter, located 5, 0, −10, and −20 μm with respect to the entrance of the filter.

The induced transmembrane potential of cells, when exposed to an external electric field, is expressed as ,52 in which VTMP is the transmembrane potential, is the magnitude of applied electric field, and τ is the relaxation time of the cell. For red blood cells, the critical transmembrane potential (beyond which pores open up within the cell membrane and eventually are lysed) is reported as 1 V,53 and the relaxation time is reported as 1 μs.52 Using these values, the critical electric field required for creating pores at a DEP frequency of 1 MHz is obtained as ∼675 kV/m, which is far beyond the maximum electric field of 197 kV/m generated in our system. Moreover, considering that the velocity of blood flowing through the primary channel is in the range of 1.1 to 1.25 mm/s, the amount of time that blood cells are exposed to strong electric fields (over a span of ∼50 μm for each microelectrode pair) is less than 42 ms, minimising the risk of damage to repelled cells. Similarly, considering that lateral velocity of plasma through the filter is estimated to be in the range of 250 to 300 μm/s, the amount of time that blood plasma is exposed to strong electric fields (over a range of 20 μm downstream of cross flow filter) is less than 80 ms, minimising the damage to filtered biomarkers.

Considering that blood has a relatively high electrical conductivity (σplasma = 1.2 S/m), the generation of strong electric fields by the microelectrode array will lead to heating of the fluid due to the Joule heating effect.50 Numerical simulations have been conducted to calculate this temperature rise within the cross flow filter and primary channel. Simulations are performed by solving differential equations governing the balance of momentum and energy of the blood flowing through the channel as well as solving energy equations within the glass substrate and PDMS slab. Due to computational limitations, our simulation considers only five microelectrode pairs.

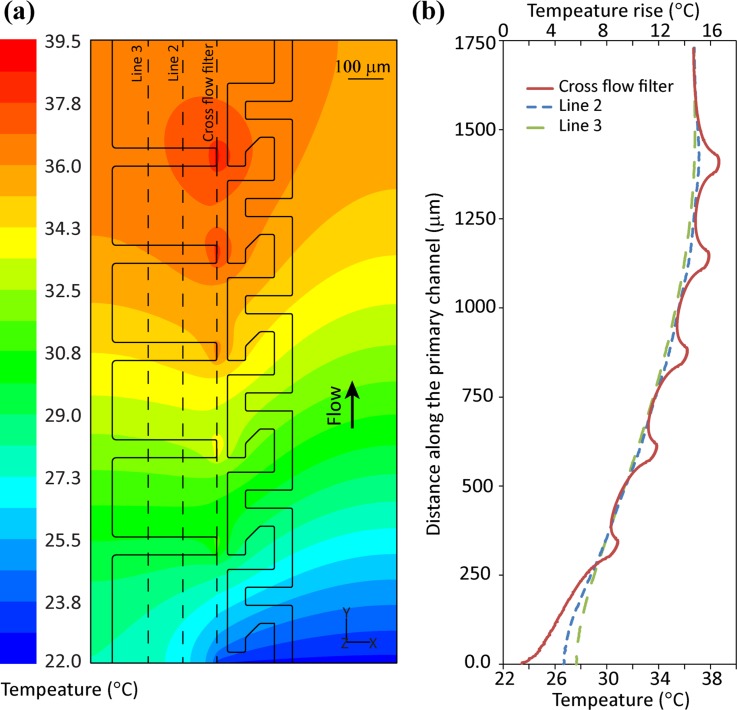

Fig. 4(a) presents the temperature distribution across the surface of the glass slide. Simulations show a constant increase in glass slide temperature until reaching a maximum value of ∼39.5 °C at the tip of the last microelectrode. Fig. 4(b) shows variations of temperature along the cross flow filter entrance, as well as two lines spaced 100 and 200 μm further within the cross flow filter. This graph shows the formation of locally sharp temperatures at areas of strong electric field, which reduce to ∼37.6 °C within 100 μm downstream of the last microelectrode tip.

FIG. 4.

(a) The temperature distribution across the surface of the glass slide and (b) the variations of temperature along three arbitrary lines along the cross flow filter, located 0, −100, and −200 μm with respect to the entrance of the cross flow filter.

Fig. 4(b) also presents the temperature rise due to Joule heating effect, showing a maximum temperature rise of ∼17.5 °C at the tip of the last microelectrode. The temperature rise can be estimated as ,50,54 in which is the root-mean-square value of the applied voltage, and is the thermal conductivity of plasma. It should be noted that the analytical equation does not take into account the effect of locally sharp electric fields at the tip of microelectrodes, the heat conduction through glass slide, and heat convection due to flow of blood. Using this equation, the temperature rise is obtained as 16.3 °C, which is close to the simulated value.

The denaturation onset temperature for various well-characterised protein constituents of blood vary from 46 to 97 °C,55,56 which is more than that of the maximum localised temperature generated within our system. Moreover, considering that lateral velocity of plasma through the filter is within the range of 250 to 300 μm/s, the amount of time that blood plasma is exposed to high temperature regions of ∼39.5 °C is less than 300 ms, minimising the risk of protein denaturing due to temperature rise.

D. Microfabrication of microfluidic chip

The implemented chip consists of two modules. An electrode array consisting of metallic electrodes deposited on a borosilicate glass slide, and a microfluidic capillary flow system consisting of channel structures embedded in PDMS. The electrode arrays were constructed using standard photolithography processes. The borosilicate glass substrate was coated with a thin layer (∼10 μm) of KMPR photoresist, and this was developed with the desired electrode shape and coated with an adhesive layer (25 nm) of titanium (evaporation deposition) and then with a conductive layer (250 nm) of gold (RF sputtering). The KMPR was then removed using lift-off process, leaving metallic electrodes patterned on the glass substrate.

The PDMS slab was patterned using standard microfabrication processes. Standard photolithographic processes were used to create protruding negative moulds of the desired structures in SU8, and uncured PDMS was then poured over this mould and cured in an oven at 70 °C. A silicon wafer was used as a substrate; this was initially uniformly coated with a thin layer of SU8 (1.2 μm). This initial coat acts as a protective layer to prevent undesired bonding of PDMS to the silicon substrate. A second 1.2 μm layer was spun over the substrate, and this was patterned with the poststructure required to support the cross flow filter; over this another layer of SU8 was deposited, and this time with a thickness of 25 μm. This final layer was patterned with the primary channel and capillary pump structures. After fabrication, the components of the chip (glass substrate and block containing PDMS structures) were aligned and placed in contact with one another. As only capillary forces are exerted upon the system, there is no need to permanently bond the glass and PDMS. Alignment is critically important to device functionality, notably alignment of the filter structure, as this must bridge the gap between the primary channel and the plasma extraction capillary pump. The electrode tips must be aligned directly under the junction between the primary channel and cross flow filter in order to effectively unblock it.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Various experiments were conducted during development of the chip in order to characterise and verify the performance of each element. The individual components of the chip were developed and tested individually, and integrated to form a fully functional whole system. All experiments conducted made use of fresh anti-coagulated blood provided through venepuncture by a healthy screened donor. The haematocrit levels are assumed to be between 40.7% and 50.3% as standard for an adult male.57 Observations of the chip and its components were made using an Olympus GX51 inverted microscope fitted with an Olympus UC30 CCD camera.

A small volume of whole blood (∼15 μl) is introduced into the sample inlet port, shown between the electrode leads on the right of Fig. 5(a). Blood flows from this reservoir, through the primary channel, and past the cross flow filter. Shear stress generated by the flow of sample past the filter entrance assists with unblocking blood cells lodged in the entrance to the filter. However, this effect alone is not capable of sustained operation as with time; the vast number of cells present in whole blood will accumulate and clog the filter entrance. To resolve this issue, the DEP electrodes are aligned along the entrance to the cross flow filter structure. When energised with an AC signal, the resulting non-uniform electric field applies a negative DEP force to blood cells, repelling them from the electrode array. This effect actively unblocks the cross flow filter entrance, preventing blood cells from becoming lodged in the filter gap and is shown in Fig. 5(b). Consistent flow of sample through the primary channel is enabled by the waste extraction capillary pump, which draws processed waste blood from the primary channel into a waste storage area, as shown in Fig. 5(c). Plasma is drawn from the primary channel, through the cross flow filter structure, and gets collected by the plasma extraction capillary pump, as shown in Figs. 5(d) and 5(e). The extreme transition in channel height from the filter structure to plasma extraction capillary pump is enabled through the use of wedge shaped capillary transition enhancers.

FIG. 5.

A. Subsystem functionality

The DEP electrode array used in this work is based on that shown in Ref. 17. This array was chosen as it has been shown to effectively repulse red blood cells within highly diluted blood. The electrode array can be seen conceptually in Fig. 1(b) and can be seen in operation in Fig. 5(b). Functionality of the DEP electrode array was verified by placing a single microfluidic channel with a width of 500 μm over the electrode array. This setup was used to characterise the effects of DEP force when applied to blood in both static and dynamic flow conditions, and was used to verify the effectiveness of the electrode array for both diluted (1:1 phosphate buffer saline solution) and whole blood. Electrodes were verified to function to a satisfactory level with undiluted blood. Repulsive performance was significantly reduced due to an increase in red blood cell count, resulting in additional granular resistance against the repulsive force applied to the target cells. The electrodes were however effective in depleting a small channel of blood to haematocrit levels low enough to not overwhelm the cross flow filter. This effect can be seen in Fig. 5(b).

The primary channel and capillary pumps were characterised in order to verify functionality of capillary pump structures, to assess the duration and speed at which they fill, and in turn the speed at which they draw sample over the DEP electrode array. Flow rate is a critical factor since, if the sample passes over the array too quickly, insufficient time is allowed for dielectrophoresis to be used to full effect. The waste extraction capillary pump, consisting of a repetitive array of 100 μm-wide channels, each with a flow rate of ∼1.5 nl/s provides a consistent flow rate within the primary channel generally within the range of flow rates in which dielectrophoresis can be used effectively. An image of the waste extraction capillary pump in operation is shown in Fig. 5(c).

As reported in Ref. 7, the optimal cross flow filter depth is around 1.2 μm; this was experimentally verified, structures shallower than 1 μm were liable to collapse due to the deformable nature of PDMS, while structures deeper than 1.2 μm experienced blood cell infiltration. The filter was characterised both with and without the assistance of active DEP unblocking. Initial tests had a similar result; the filter volume filled relatively quickly (less than 60 s after sample insertion). However, initial testing identified that the plasma was unable to make the phase transition from the shallow filter structure (1.2 μm) to the deeper (25 μm) plasma extraction channels.

Experiments conducted using a filter lacking transition enhancers reinforced the vital role of capillary phase transition enhancement structures modulating capillary pressure between the cross flow filter and plasma extraction capillary pump.

Experimental results using filters incorporating transition enhancers verified the theory outlined in supplementary Fig. S1.49 These experiments identified a long asymmetrically tapered structure, shown conceptually in Fig. 1(c), and in operation in Fig. 5(d), as an effective means of adding high capillary force to an area of the filter close to the DEP array. These transition enhancers create a graduated capillary force, which is high at the tip, encouraging plasma to flow from the 1.2 μm deep filter into the ∼7 μm wide, 25 μm deep transition enhancer tip. Capillary forces then decrease as the channel widens, until they match that of the plasma extraction capillary pump at 100 μm. These structures have the additional benefit of reducing the flow resistance of the cross flow filter structure as they are significantly deeper channels that intersect the complex geometry of the filter structure, allowing a path of lower resistance. The impact of these enhancers is shown graphically in Fig. 6, with a plot comparing extracted plasma volume of the complete system incorporating transition enhancers against the same configuration without enhancers.

FIG. 6.

Performance of the system is characterised by plotting extracted plasma volume against time in minutes. Active DEP unblocking (green) is shown to markedly increase plasma extraction volumes with respect to the same system without applied DEP (red). System without capillary transition enhancer structures (blue dashed) illustrates the positive effect capillary transition enhancers have in allowing for large-scale plasma extraction capillary pumps.

B. Integrated system functionality

The integrated system was tested with experiments initially running with the DEP electrodes inactive. This initial test series was used to verify the effectiveness of dielectrophoresis in unblocking the filter, by providing a benchmark of how the cross flow filter would function alone in the final configuration. The result was similar to the expected outcome. The system was effective at extracting a small volume of plasma; however, after a short time (<10 min), the filter became overwhelmed, and the extraction rates dropped. The average volume of plasma extracted in this configuration over a 15 min period was 17 nl with the maximum volume achieved 33 nl.

The test sequence was repeated in the same configuration with DEP electrodes energised with an 8 V peak-to-peak, 1 MHz AC signal. The increase in extracted volume was significant. The average volume extracted over 15 min was 165 nl with the maximum achieved 194 nl. Operation of the integrated system is presented in Fig. 5 (Multimedia view). The results of this experiment are shown in Fig. 6. Extracted plasma yield for these experiments was calculated by measuring the distance covered by the plasma meniscus in each capillary pump channel. The distance covered was measured using Olympus smart image stream Microscope image capture software; as the channel geometry is known, the volume can be calculated. The same strategy was used to calculate the volume of the capillary transition enhancer structures and cross flow filter, although due to its low profile, the volume of plasma stored in the filter structure is negligible compared to that of the capillary transition enhancers or plasma extraction capillary pump.

Overall system performance metrics are provided in Table I, showing plasma volume extracted as a function of time. The system is capable of operation in excess of 40 min; however, as a point-of-care system must provide rapid results, only the first 15 min are characterised. Based on the achieved results, extracted plasma efficiency is on the order of 1.1%, which is slightly higher than expected value for a cross flow filtration system using whole human blood reported in the literature.6

TABLE I.

Performance metrics for experimental extraction volumes.

| System configuration | 5 min | 10 min | 15 min |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excluding capillary transition enhancers (no DEP) | 10 nl | 10 nl | 10 nl |

| Capillary transition enhancers present (no DEP) | 9 nl | 15 nl | 17 nl |

| Capillary transition enhancers present (DEP active) | 63 nl | 130 nl | 165 nl |

The primary advantage of this extraction approach is the ability to effectively extract plasma from undiluted whole blood, with the intention of eliminating blood dilution steps, and more importantly retaining biomarker concentrations that may otherwise be diluted to undetectable levels. It should be noted that the extracted plasma volume and plasma extraction efficiency are both improved, when measured against a comparable system, such as the one presented in Ref. 17. This system is used to extract 300 nl of diluted plasma from a 5 μl droplet of 1:9 blood-PBS diluted samples. In comparison, our system is able to extract 165 nl of plasma from a 15 μl droplet of undiluted blood. Taking dilution into account, the extracted volume of plasma provided by our approach is increased by a factor of 5.5 while the extraction efficiency is increased by a factor of 1.8.

The approach presented in Ref. 17 relies on repelling of blood cells from the microelectrode tips and traps them within the regions of weak electric field gradient. While this is effective in highly diluted blood samples, the technique is not suitable for whole blood where the high density of blood cells would block the filter entrance, reducing the effectiveness of this technique for extraction of plasma. Our work, on the other hand, addresses this issue with the introduction of a waste capillary pump, which is used to supply a continuous flow of blood through the primary channel. This flow provides sufficient shear stress to drag repelled blood cells away from the filter, as well as resupply fresh blood to the cross flow filter. This in turn extends the operational duration and increases the volume of extracted plasma. The continuous flow of blood through the primary channel also mitigates localised high temperature zones at microelectrode tips, generated due to the Joule heating effect, which could potentially damage biomarkers present within the blood plasma, or lead to lysis of blood cells, contaminating the plasma sample.

IV. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

This paper presents an enhanced plasma extraction method that addresses many of the problems present in the currently available microfluidic based plasma extraction technologies. This approach is capable of extracting relatively high volumes of plasma from undiluted whole blood, eliminating the requirement of external blood dilution steps, while performing as a stand-alone chip, not requiring external pumping systems. These factors make this approach uniquely suitable for cheap and simple to use point-of-care devices.

Future work on this system will include optimisation of microelectrodes to expand the cell-free region within the primary channel while operating at low voltages, and doping of the PDMS block with surfactant to dramatically increase capillary forces, as outlined in Ref. 7.

Upon further refinement, this plasma extraction microfluidic system could be integrated with various on-chip biomarker detection methods designed for analysis of biological analyte in the nano-litre scale. These methods include a variety of integrated optical,40,41 electrochemical,43 and direct photonic biosensing techniques,42 which enable multiplexed detection of protein biomarkers, or other detection methods that could be adapted or refined to function with the volumes of analyte produced by this system.58–60 In the case of immunoassay based detection methods,40,41 the surface of the plasma extraction capillary pump channels could be coated with various capture antibodies to enable selective capturing of target protein from the plasma. Capture antibodies could alternatively be coated onto a reaction well placed between the capillary transition enhancer structures and plasma extraction capillary pump.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.K. gratefully acknowledges funding from Verbund der Stifter at the University of Applied Sciences Karlsruhe, the Struktur- und Innovationsfonds für die Forschung in Baden-Württemberg (SI-BW) and the German Research Foundation (DFG), Grant Nos. INST 55/3-1 and INST 55/2-1. C.S. would like to express thanks to benefactors of the Professor Robert and Josephine Shanks Scholarship, and he is indebted to the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung for the financial support by the Baden-Württemberg-STIPENDIUM for University Students—BWS plus, a program of the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung. The authors also acknowledge Marlene Rodrigues from the Städtisches Klinikum Karlsruhe for her assistance regarding biological aspects of the experimental process.

References

- 1. Toner M. and Irimia D., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 7, 77 (2005). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.011205.135108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hou H. W., Bhagat A. A. S., Lee W. C., Huang S., Han J., and Lim C. T., Micromachines 2(3), 319–343 (2011). 10.3390/mi2030319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kersaudy-Kerhoas M. and Sollier E., Lab Chip 13(17), 3323–3346 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50432h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tripathi S., Kumar Y. V. B. V., Prabhakar A., Joshi S. S., and Agrawal A., J. Micromech. Microeng. 25(8), 083001 (2015). 10.1088/0960-1317/25/8/083001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ji H. M., Samper V., Chen Y., Heng C. K., Lim T. M., and Yobas L., Biomed. Microdevices 10(2), 251–257 (2008). 10.1007/s10544-007-9131-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crowley T. A. and Pizziconi V., Lab Chip 5(9), 922–929 (2005). 10.1039/b502930a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim Y. C., Kim S.-H., Kim D., Park S.-J., and Park J.-K., Sens. Actuator, B 145(2), 861–868 (2010). 10.1016/j.snb.2010.01.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen X., Cui D. F., Liu C. C., and Li H., Sens. Actuator, B 130(1), 216–221 (2008). 10.1016/j.snb.2007.07.126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuo J.-N. and Zhan Y.-H., Microsys. Technol. 21, 255–261 (2015). 10.1007/s00542-013-2048-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeh C.-H., Hung C.-W., Wu C.-H., and Lin Y.-C., J. Micromech. Microeng. 24(9), 095013 (2014). 10.1088/0960-1317/24/9/095013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li C., Liu C., Xu Z., and Li J., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 12(5), 829–834 (2012). 10.1007/s10404-011-0911-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu C., Mauk M., Gross R., Bushman F. D., Edelstein P. H., Collman R. G., and Bau H. H., Anal. Chem. 85(21), 10463–10470 (2013). 10.1021/ac402459h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. VanDelinder V. and Groisman A., Anal. Chem. 78(11), 3765–3771 (2006). 10.1021/ac060042r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang X.-B., Wu Z.-Q., Wang K., Zhu J., Xu J.-J., Xia X.-H., and Chen H.-Y., Anal. Chem. 84(8), 3780–3786 (2012). 10.1021/ac3003616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nahavandi S., Baratchi S., Soffe R., Tang S.-Y., Nahavandi S., Mitchell A., and Khoshmanesh K., Lab Chip 14(9), 1496–1514 (2014). 10.1039/c3lc51124c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lenshof A., Ahmad-Tajudin A., Jaürås K., Swärd-Nilsson A.-M., Åberg L., Marko-Varga G. r., Malm J., Lilja H., and Laurell T., Anal. Chem. 81(15), 6030–6037 (2009). 10.1021/ac9013572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakashima Y., Hata S., and Yasuda T., Sens. Actuator, B 145(1), 561–569 (2010). 10.1016/j.snb.2009.11.070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dimov I. K., Basabe-Desmonts L., Garcia-Cordero J. L., Ross B. M., Ricco A. J., and Lee L. P., Lab Chip 11(5), 845–850 (2011). 10.1039/C0LC00403K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee K. K. and Ahn C. H., Lab Chip 13(16), 3261–3267 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50370d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jia Y., Ren Y., and Jiang H., Electrophoresis 36(15), 1744–1753 (2015). 10.1002/elps.201400565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prabhakar A., Kumar Y. V. B. V., Tripathi S., and Agrawal A., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 18, 995–1006 (2015). 10.1007/s10404-014-1488-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mohammadi M., Madadi H., and Casals-Terré J., Biomicrofluidics 9(5), 054106 (2015). 10.1063/1.4930865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pethig R., Biomicrofluidics 4(2), 022811 (2010). 10.1063/1.3456626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khoshmanesh K., Nahavandi S., Baratchi S., Mitchell A., and Kalantar-zadeh K., Biosens. Bioelectron. 26(5), 1800–1814 (2011). 10.1016/j.bios.2010.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Demircan Y., Özgür E., and Külah H., Electrophoresis 34(7), 1008–1027 (2013). 10.1002/elps.201200446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li M., Li W. H., Zhang J., Alici G., and Wen W., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 47(6), 063001 (2014). 10.1088/0022-3727/47/6/063001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jubery T. Z., Srivastava S. K., and Dutta P., Electrophoresis 35(5), 691–713 (2014). 10.1002/elps.201300424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang C., Smith J. P., Saha T. N., Rhim A. D., and Kirby B. J., Biomicrofluidics 8(4), 044107 (2014). 10.1063/1.4890466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuczenski R. S., Chang H.-C., and Revzin A., Biomicrofluidics 5(3), 032005 (2011). 10.1063/1.3608135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Piacentini N., Mernier G., Tornay R., and Renaud P., Biomicrofluidics 5(3), 034122 (2011). 10.1063/1.3640045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Auerswald J. and Knapp H. F., Microelectron. Eng. 67, 879–886 (2003). 10.1016/S0167-9317(03)00150-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Menachery A., Kremer C., Wong P. E., Carlsson A., Neale S. L., Barrett M. P., and Cooper J. M., Sci. Rep. 2, 775 (2012). 10.1038/srep00775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pommer M. S., Zhang Y., Keerthi N., Chen D., Thomson J. A., Meinhart C. D., and Soh H. T., Electrophoresis 29(6), 1213–1218 (2008). 10.1002/elps.200700607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith J. P., Huang C., and Kirby B. J., Biomicrofluidics 9(1), 014116 (2015). 10.1063/1.4908049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu C., Wang Y., Cao M., and Lu Z., Electrophoresis 20(9), 1829–1831 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mohammadi M., Madadi H., Casals-Terré J., and Sellarès J., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407(16), 4733–4744 (2015). 10.1007/s00216-015-8678-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yan S., Zhang J., Alici G., Du H., Zhu Y., and Li W., Lab Chip 14(16), 2993–3003 (2014). 10.1039/C4LC00343H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen C.-C., Lin P.-H., and Chung C.-K., Lab Chip 14(12), 1996–2001 (2014). 10.1039/c4lc00196f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Javanmard M., Emaminejad S., Gupta C., Provine J., Davis R. W., and Howe R. T., Sens. Actuator, B 193, 918–924 (2014). 10.1016/j.snb.2013.11.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Diercks A. H., Ozinsky A., Hansen C. L., Spotts J. M., Rodriguez D. J., and Aderem A., Anal. Biochem. 386(1), 30–35 (2009). 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu W., Chen D., Du W., Nichols K. P., and Ismagilov R. F., Anal Chem. 82(8), 3276–3282 (2010). 10.1021/ac100044c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dinish U. S., Fu C. Y., Soh K. S., Ramaswamy B., Kumar A., and Olivo M., Biosens. Bioelectron. 33(1), 293–298 (2012). 10.1016/j.bios.2011.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Han J.-H., Lee D., Chew C. H. C., Kim T., and Pak J. J., “ A multi-virus detectable microfluidic electrochemical immunosensor for simultaneous detection of H1N1, H5N1, and H7N9 virus using ZnO nanorods for sensitivity enhancement,” Sens. Actuator, B (in press). 10.1016/j.snb.2015.07.068 [DOI]

- 44. Diez-Silva M., Dao M., Han J., Lim C.-T., and Suresh S., MRS Bull. 35(05), 382–388 (2010). 10.1557/mrs2010.571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paulus J. M., Blood 46(3), 321–336 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Juncker D., Schmid H., Drechsler U., Wolf H., Wolf M., Michel B., de Rooij N., and Delamarche E., Anal. Chem. 74(24), 6139–6144 (2002). 10.1021/ac0261449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zimmermann M., Schmid H., Hunziker P., and Delamarche E., Lab Chip 7(1), 119–125 (2007). 10.1039/B609813D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Safavieh R. and Juncker D., Lab Chip 13(21), 4180–4189 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50691f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4938391E-BIOMGB-9-022506 for 1. Principles of capillary pump operation, 2. Waste extraction capillary pump, 3. Plasma extraction capillary pump, 4. Calculation of Re(fCM) for red blood cells, and 5. Numerical analysis of electric field and DEP force.

- 50. Morgan H. and Green N. G., AC Electrokinetics: Colloids and Nanoparticles ( Research Studies Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gascoyne P., Mahidol C., Ruchirawat M., Satayavivad J., Watcharasit P., and Becker F. F., Lab Chip 2(2), 70–75 (2002). 10.1039/b110990c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chang D. C., Biophys. J. 56(4), 641–652 (1989). 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82711-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. K. Kinosita, Jr. and Tsong T. Y., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 554(2), 479–497 (1979). 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90386-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grom F., Kentsch J., Müller T., Schnelle T., and Stelzle M., Electrophoresis 27(7), 1386–1393 (2006). 10.1002/elps.200500416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wetzel R., Becker M., Behlke J., Billwitz H., Bohm S., Ebert B., Hamann H., Krumbiegel J., and Lassmann G., Eur. J. Biochem. 104(2), 469–478 (1980). 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Raeker M. Ö. and Johnson L. A., J. Food Sci. 60(4), 685–690 (1995). 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1995.tb06206.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vajpayee N., Graham S., and Bem S., Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods ( Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007), pp. 465–468. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ranzoni A., Sabatte G., van Ijzendoorn L. J., and Prins M. W. J., ACS Nano 6(4), 3134–3141 (2012). 10.1021/nn204913f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Losoya-Leal A., Estevez M. C., Martínez-Chapa S. O., and Lechuga L. M., Talanta 141, 253–258 (2015). 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Luchansky M. S., Washburn A. L., McClellan M. S., and Bailey R. C., Lab Chip 11(12), 2042–2044 (2011). 10.1039/c1lc20231f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4938391E-BIOMGB-9-022506 for 1. Principles of capillary pump operation, 2. Waste extraction capillary pump, 3. Plasma extraction capillary pump, 4. Calculation of Re(fCM) for red blood cells, and 5. Numerical analysis of electric field and DEP force.