Abstract

Background:

Happiness has a considerable impact on elderly quality of life. Reminiscence therapy can be an effective intervention in increasing the positive emotions among elderly.

Objectives:

This study was performed to investigate the effect of reminiscence therapy on Iranian elderly women’s happiness.

Patients and Methods:

This randomized clinical trial conducted on 32 elderly women (census sampling) attending the jahandidegan daycare elderly center IN Gorgan city, Iran, in 2013. Happiness scores of 4 phases were measured: before, the third session, the sixth session and one month after the intervention. Three instruments were used in this study including a demographic questionnaire, the mini mental state examination test, and Oxford happiness questionnaire. The intervention group participated in six sessions of narrative group reminiscence that were held in three consecutive weeks, two sessions per week. The control group was also participated in six sessions of group discussions that were held in three consecutive weeks, two sessions per week. Data analysis was performed the chi-square, independent t-test, Paired t-test.

Results:

From a total of 32 elderly women, 29 cases completed the study. No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics. The mean happiness scores before the intervention between the two groups were not significantly different (P = 0.824). Comparison of the mean happiness scores of the intervention group in the four measurement times revealed a significant difference only after the third and sixth sessions (P = 0.03), and no significant difference was found between the mean happiness scores of the control group in the four measurement times.

Conclusions:

The elderly participating in the matched group sessions can be effective in increasing positive emotions.

Keywords: Autobiography, Agedly, Happiness, Women

1. Background

The pursuit of happiness is an important goal for all human generations and is the most central human stimuli (1). Happiness is a psychological concept with several definitions and dimensions (2). Happiness is the degree to which people judge their life quality. It is a positive emotion, associated with life satisfaction and absence of negative feelings. It also is an important criterion for psychological wellbeing (3). It has been shown that happiness can lead to a favorable attitude towards life, a positive self-concept, higher levels of vitality and mental health; proper affect, and higher levels of social and physical functioning (4, 5). Happiness is also associated with increased physical and psychological wellbeing, better sleep, reduced levels of stress hormones, improvements in cardiovascular functioning (1), increased longevity (6), better adaptability in face of life events, strengthening the immune system (7), increased quality of life (8), feeling of more comfort and security, and will eventually lead to life satisfaction (9).

Aging is an inevitable life event, but accompanies great risks for the man’s physical and mental health (10). The world population is aging. Since 1980, the world population aged 60 years and over has doubled and is forecast to reach 2 billion people by 2050 (11). The proportion of older women is greater than men so that 54% of those 60 and older are women (12). Aged people experience a vast range of bio-psycho-social changes that predispose them to psychological disorders (13). It has been reported that 15% to 46% of elderly suffer from symptoms of psychiatric and mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, memory loss, changes in sleep pattern, feelings of loneliness and social isolation (14, 15). Despite the improvements in the global health and in social and economic indicators, yet there are differences in older women’s socio-demographics than men (16). It has been shown that women have lower social status, have access to lower levels of social support and are more prone to depressive and anxiety disorders (17).

In addition, levels of happiness and vitality of elderly is diminished with increasing age (18). Also, retirement and loss of job and social positions, loss of a loved one, diminished levels of health, decreased sensory perceptions and changes in self-image, would negatively affect the seniors’ psychological wellbeing and happiness, especially in elderly women (19). Given the effects of happiness on different aspects of life, it is needed to examine the effects of some joyful interventions on happiness of elderly and especially in older women. It has been shown that positive psychology and recovery approaches could improve the seniors’ mood, promote their social and economic conditions and help them to enjoy a productive life (20). Psychotherapy (21), cognitive behavioral therapy (22), positive psychological interventions (23) and reminiscence therapy (24) are among psychological interventions have been used to improve self-esteem, socialization, life satisfaction and happiness in elderly people (25).

Reminiscence therapy is an alternative to the traditional method of psychotherapy with older adults. Reminiscence is based on reviewing life events, feelings and previous thoughts, in order to facilitate a sense of joy, enhance the quality of life, or adapt to current situations (25). In reminiscence, elderly reviews his/her life focusing on the Erickson’s life-span developmental theory (26). Reminiscence helps the elderly to restore life events and place them in a new mental structure to expand their understanding of the life meaning (27).

American nursing association has recognized reminiscence therapy as an independent nursing intervention (28). This intervention can be used both in hospitals and in nursing homes to improve the quality of life, memory and awareness of elderly and promote their health (21, 29). Studies have been shown that reminiscence is effective in improving the individual’s perception of the current situation; strengthening self-esteem, reducing depressive symptoms, disappointment and negative emotions such as anxiety (30-32). Reminiscence also enhances the elders’ ability to recall good things and solve the present problems, It also improves the elders’ feeling of pleasure, security, health, identity, belonging, death preparation, intimacy (33) and overall psychological health and wellbeing. However, in a meta-analysis, Bohlmeijer et al. showed that reminiscence had the modest effect on life satisfaction and well-being of older adults (34). Majzoobi et al. have also studied the effectiveness of the structured group reminiscence on the elderly’s life quality and happiness. The results indicated that the intervention was effective on happiness while did not significantly affect the life quality (35) Also, Momeni and Wang have reported that the reminiscence therapy did not significantly affect the depressive symptoms, mood, self-esteem and health perception in elderly people (30, 36). Also, inconsistent results have been reported in studies conducted on reminiscence therapy in elderly with depression or mental disorders (25, 28, 37).

Reminiscence therapy has frequently been used in areas of depression, dementia, loneliness, and quality of life (21, 25, 38). However, it was rarely used in areas of positive psychology and happiness in the elderly population and especially in elderly women. Reminiscence therapy is an inexpensive and safe method (33) and most of studies on reminiscence therapy were conducted in western countries and the East Asia, while in Iran studies of reminiscence therapy are still rare. There are cultural differences between Iran and other countries and such differences may affect the outcomes of the reminiscence therapy.

2. Objectives

Due to the cultural differences between Iran and other western and Asian countries, this study aimed to investigate the effect of the group reminiscence therapy on happiness of a sample of Iranian elderly women.

3. Patients and Methods

This randomized clinical trial was conducted on elderly women attending a daycare Jahandidegan daycare elderly center in Gorgan City, Iran, in 2013. The daycare center is a non-governmental charity that provides a range of daily religious, recreational, cultural, sporting, artistic and educational services to the elderly people. Elderly are attending part-time at the center and then return home.

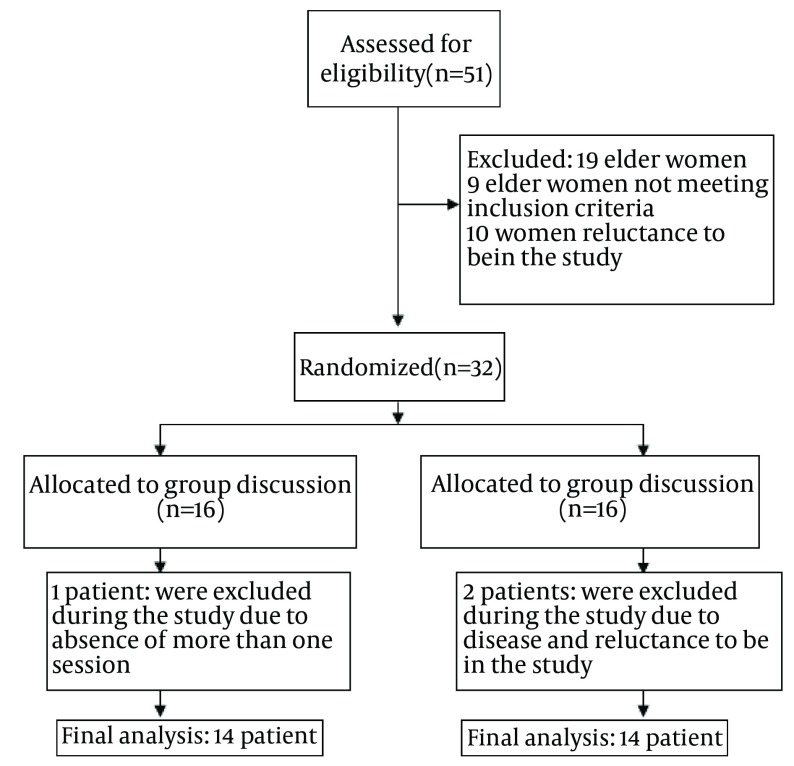

With census sampling, all the elderly women met inclusion criteria, regularly referred to the center and volunteered to participate in the study (n = 32) were recruited and then were assigned into the intervention and control groups using a randomized block sampling method. The inclusion criteria were: age of 60 years and over, absence of hearing impairment, the ability to speak Persian, being literate, having no cognitive impairment (obtaining a score over 20 based on mini mental state examination (MMSE)), not suffering from a known psychiatric disorders, physical ability to attend in meetings, and consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included occurring any long-term hearing problems during the study (e.g. a mal-performance in a subject’s hearing aid), using antipsychotic or psycho stimulant medications during the study due to a psychological problem, an absence of more than one session, experiencing a severe family crises during the study (family bereavement, a sudden serious illness in a family member), serious illness resulting in hospitalization, lack of cooperation during the study. (The study framework is presented in Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Consort Flowchart Describing the Progress of Subjects Through the Study.

3.1. Instruments

Three instruments were used in this study including a demographic questionnaire, the MMSE test, and Oxford happiness questionnaire (OHQ). The demographic questionnaire included 14 questions (including: age, education level, occupation, financial status, marital status, number of children, smoking, family supports, religions, having a known disease, type of abode and living arrangement). Content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by 10 faculty members in Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

The MMSE test is a brief 11-point questionnaire that is used to screen for cognitive impairment. It assesses the subject’s mental functions in a number of areas including the orientation to time and place, alertness, attention, calculation and memory. The MMSE has demonstrated validity and reliability in psychiatric, neurologic, geriatric, and other medical populations. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the test was calculated (α = 0.78). In the Foroughan study, It also demonstrated good sensitivity (90%) and specificity (84%) at cut-off point of 21 (39). This test has the minimum and maximum scores of zero and 30, respectively. Any score greater than or equal to 24 points indicates a normal cognition. Below 24 points Also, scores can indicate mild (20 - 23 points), moderate (10 - 19 points) or severe (≤ 9 points) cognitive impairment (40).

The OHQ includes 29 items and in this study were used to measure people’s happiness. All items rated on a Likert scale from zero to 3 with the minimum and maximum scores of zero and 87, respectively. The higher the score, the higher the subject’s happiness will be (41). The Persian version of the OHQ has been validated by Alipoor and Noorbala (42) and has been demonstrated a good validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93).

3.2. Intervention

After explaining the study objectives and obtaining the participants’ written informed consent and through individual interviews, the MMSE test was conducted in a quiet place. Then everyone obtained a score over 20 were enrolled in the study. Afterward, the participants were allocated into the intervention and control group and each group was divided into 2 subgroups of 7 - 8 subjects.

Each subgroup of the intervention group participated in six sessions of the narrative group reminiscence that were held in three consecutive weeks, two sessions per week. Each session lasted for 1.5 - 2 hours. In each session, participants recalled their memories focused on a specific theme. No interpretation or judgment was made on the participants’ memories.

The narrative group reminiscence therapy sessions were conducted using the reminiscence therapy manual proposed by Watt and Cappeliez. According to the manual, intervention consisted of six sessions focused on different themes as follows: major decisive events of life, family life, career or major life work and personal interests, stress experiences, loves and hates, and beliefs on the meaning and goals of life (43).

The first session began with a welcome to members by the group facilitator and continued with the facilitator and participants’ self-introductions to get familiar with each other. Then, the group facilitator presented the objectives, structure and the main rules of meetings. At the beginning of each session, time was designated to everyone (about 10 - 15 minutes, depending on the issue) so that everybody can present her memories in the group. Days before each session subjects were contacted to remind them about the session. At the start of each session, the group facilitator invited the participants to share her memories about the predetermined theme. The first participant started to talk voluntarily and then other participants expressed their memories. When an elderly was presenting her memories, the other group members were required to listen and give no comment or judgment unless the group facilitator request them. At the end of each session, the members were acknowledged by the group facilitator. Then the theme of the next session was presented and the participants were asked to prepare themselves for the next session. This could help the participants refamiliarize themselves with the memory and the context in which it occurred, made them ready to be involved in the next session and helped to use the time of the sessions more efficiently.

Each subgroup of the control group was also participated in six sessions of group discussions that were held in three consecutive weeks, two sessions per week. The topic of the discussions was selected at the start of each session through group agreement.Both in the intervention and control group, the demographic questionnaire and the OHQ inventory were initially completed before the first session. Then the OHQ inventory was repeated immediately after the third and the sixth session and also one month after the intervention.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This study received ethical approval from the institutional review board and the research ethics committee of Kashan university of medical sciences, No: P/29/5/1/1700 dated 1 July. 2013. Also, permission was sought from the authorities of the daycare elderly center of the Gorgan city. All the elderly participants signed a written informed consent before participation and were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information. Also, they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (version 21, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to test the differences between nominal demographic variables of the both groups. Independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare the mean of quantitative demographic variables of the two groups. We used Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality of data, Paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to examine the differences in the mean scores of happiness in different times. Also, for multivariate analysis of effects of different factors on elderly happiness analysis of variance with repeated measurement and bootstrap for P Value estimation in this model was used. P Value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant in all tests.

4. Results

From a total of 32 elderly women, three women were excluded during the study due to disease, reluctance to be in the study, or absence of more than one session, and 29 ones completed the study.

No significant differences were found between the intervention and the control groups in terms of demographic characteristics (Tables 1 and 2). The mean age of the elderly women in the intervention group was 66.20 ± 7.41 and in the control group was 64.29 ± 5.25 years. In total, 66.7% in the intervention group and 64.3% in the control group were married. Also, 57.1% of the intervention group and 40% of the control group had a known physical disorder. The mean MMSE score was 25.53 ± 2.10 in the intervention group and 26.64 ± 2.10 in the control group (P = 0.258).

Table 1. The Status Demographic and (Qualitative) Background Variables in the Experimental and Control Groups.

| Variable | Control (N = 14) a | Experimental (N = 15) a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | P > 0.999 b | ||

| Guidance and Primary | 13 (92.9) | 10 (66.7) | |

| High school | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | |

| University | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Job | P > 0.999 b | ||

| Retired | 1 (7.1) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Housekeeper | 13 (92.9) | 13 (86.7) | |

| Financial status | P > 0.999 b | ||

| Moderate | 10 (71.4) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Good | 4 (28.6) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Marital Status | P > 0.999 b | ||

| Widow | 5 (35.7) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Married | 9 (64.3) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Family support | 0.875 b | ||

| Very low | 2 (14.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Middle | 8 (57.1) | 7 (46.7) | |

| High | 4 (28.6) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Religious beliefs | 0.78 b | ||

| Too much | 8 (57.1) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Relatively high | 2 (14.3) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Moderate | 3 (21.4) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Few | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Physical illness | 0.35 b | ||

| Have | 6 (40.0) | 8 (57.1) | |

| Have not | 9 (60.0) | 6 (42.9) | |

| Residential house | 0.33 b | ||

| Personal Property | 13 (92.9) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Rental | 1 (7.1) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Life style | 0.75 c | ||

| With children | 4 (24.1) | 3 (13.3) | |

| With wife and children | 9 (64.3) | 9 (60.0) | |

| Alone | 1 (7.1) | 3 (20.0) |

a Values are presented as No. (%).

b Fisher’s exact test.

c Chi-square test.

Table 2. Status Quantitative Demographic Variables in the Experimental and Control Groups a.

| Variables | Experimental (N = 15) b | Control (N = 14) b | P Value c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 66.20 ± 7.418 | 64.29 ± 5.254 | 0.87 |

| Number of children | 3.80 ± 1.897 | 3.86 ± 1.292 | 0.60 |

| Score MMSE | 25.53 ± 2.100 | 26.64 ± 2.098 | 0.25 |

a Abbreviation: MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

b Values are presented as mean ± SD.

c Independent t-test.

The mean happiness score before the intervention was 43.20 ± 8.22 in the intervention group and 42.36 ± 11.77 in the control group and these scores were not significantly different (P = 0.824) (Table 3).

Table 3. The Mean and Standard Deviation of Happiness in Both Groups Before, During and After the Intervention.

| Measurement time | Control (N = 14) a | Experimental(N = 15) a | P Value t-test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 42.36 ± 11.777 | 43.20 ± 8.222 | 0.82 |

| The third session | 43.07 ± 11.425 | 43.80 ± 8.082 | 0.84 |

| Sixth session | 43.50 ± 10.603 | 46.93 ± 8.093 | 0.33 |

| A month after the end of intervention | 42.43 ± 10.025 | 45.73 ± 9.145 | 0.36 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

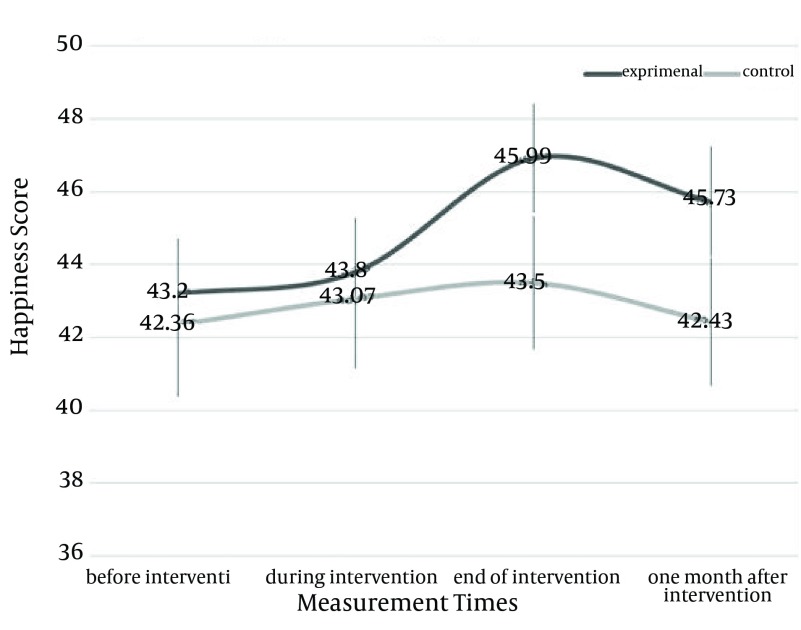

Comparison of the mean happiness scores of the intervention group in the four measurement times revealed a significant difference only after the third and sixth sessions (P = 0.03). However, no significant difference was found between the mean happiness scores of the control group in the four measurement times (Table 4 and Figure 2). Also, multivariate analysis showed the effects of the time factor check and interactions with the treatment groups, level of education, marital status, family support, lifestyle, MMSE score, on score of happiness among elderly was effective (P < 0.05).

Table 4. Mean and Standard Deviation of Happiness Scores in Each Group at Various Times.

| Measurement time | Experimental (N = 15) a | P Value of paired t-test | Control (N = 14) a | P Value of paired t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 8.222 ± 43.20 | 0.76 | 42.36 ± 11.777 | 0.21 |

| During intervention | 43.80 ± 8.082 | 0.76 | 43.07 ± 11.425 | 0.21 |

| Before intervention | 8.222 ± 43.20 | 0.06 | 42.36 ± 11.777 | 0.17 |

| End of intervention | 8.093 ± 46.93 | 0.06 | 43.50 ± 10.603 | 0.17 |

| Before intervention | 8.222 ± 43.20 | 0.211 | 42.36 ± 11.777 | 0.94 |

| One month after intervention | 45.73 ± 9.145 | 0.211 | 42.43 ± 10.052 | 0.94 |

| During intervention | 43.80 ± 8.082 | 0.03 b | 43.07 ± 11.425 | 0.45 |

| End of intervention | 8.093 ± 46.93 | 0.03 b | 43.50 ± 10.603 | 0.45 |

| During intervention | 43.80 ± 8.082 | 0.24 | 43.07 ± 11.425 | 0.35 |

| One month after intervention | 45.73 ± 9.145 | 0.24 | 42.43 ± 10.052 | 0.35 |

| End of intervention | 8.093 ± 46.93 | 0.20 | 43.50 ± 10.603 | 0.09 |

| One month after intervention | 45.73 ± 9.145 | 0.20 | 42.43 ± 10.052 | 0.09 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b P Value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant in all tests.

Figure 2. Mean Happiness Scores of Two Groups in Measurement Times.

5. Discussion

The present study showed that group reminiscence could significantly increase the mean happiness score of the intervention group. However, no significant differences were observed between the mean happiness scores of the two groups at different measurements. The nonsignificant difference between the two groups may be attributed to the nature of treatment in the control group. It seems that the elderly group conversation on interesting issues had some positive effects on their happiness. Our findings is consistent with the results of Pinquart et al. who reported that nonspecific interventions in the control group (such as discussions on the current events) may be a source for positive feelings (44). Therefore, it can be said that the elderly participation in nonspecific group conversations, especially if the group is matched for age and gender, can improve their emotions. However, the small sample size of the present study may also be effective in achieving such results. Several previous studies have also reported mixed results about the effects of reminiscence on various aspects of mental health. In a quasi-experimental study, Bohlmeijer et al. reported that integrative reminiscence significantly improved the overall meaning of life, self-evaluation and social relations of elderly participants (45). In another study, Willemse showed that although reminiscence could significantly improve life satisfaction in elderly with a mental disorder, but did not have the same effect on their depressive symptoms (37). However, Arkoff et al. reported that retrospective-proactive life review had no significant effect on mental health of older women (46). Also, in a study on the effects of group reminiscence therapy, Chao et al. have reported that this method improved the old people’s self-esteem but had no significant effect on depression and life satisfaction (25). Moreover, Stinson and Kirk have reported that structured reminiscence had no significant effects on depressive symptoms and self- transcendence of older women living in a nursing home (28). The method of reminiscence used in the present study was narrative and this may also have an effect on the results. In a related study, the elderly only reviewed their memories and no interpretations were made (47); this is consistent with the results of Momeni who reported that narrative reminiscence had no significant effect on depressive symptoms of elderly women (36).

The present study showed that mean happiness scores of the elderly women in the reminiscence group had an increasing trend during the study, although it was slightly decreased one month after the intervention. Then, it can be concluded that reminiscence could help the elderly women not only review their past experiences, but also help them internally reappraise their past. This led them to a better attitude toward their past, which consequently resulted in higher levels of happiness. Although the slight decreases in the mean happiness score one month after the intervention may be attributed to the temporary effects of the narrative reminiscence. The latter interpretation is consistent with the results of Cappeliez et al. (48), and Gudex et al. (49), who studied functions and consequences of reminiscence. They supported that although reminiscences amplifies positive emotions in elderly, emotions triggered by narrative reminiscences appear to be transient as it provides limited insight toward oneself and the present time, as the two cornerstone for permanent positive emotions and happiness (50). Achieving an enduring happiness seems to need a longer intervention. Also, happiness is a relatively stable state while the items in the OHQ assess one’s general judgment about his/her areas. Then, producing long-term changes in the people’s general judgments need longer interventions than that of the present study.

Overall, the current study indicates that reminiscence is not only an opportunity for elderly to tell the others their meaningful aspects of life events but also help them to reappraise their emotional state. Given the simple, inexpensive, and harmless nature of this technique and its effect on depressive symptoms in elderly, it is suggested that reminiscence programs be used more extensively in elderly population.

The limitations of this study are the small sample size and lack of a control group without any intervention and the strength is practical, operational and the easy solution way for increasing happiness of elderly people.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful of the research deputy of Kashan university of medical sciences, authorities in the Gorgan elderly daycare center and all the elderly women who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:All of the authors had a key role in the process of designing the research. Zahra Yousefi: design, data collection and drafting; Hossien Akbari: data analysis, and observer; Khadijeh Sharifi: design and preparation of the final version; Zahra Tagharrobi: supervisor, participation in the design and editing the final version.

Funding/Support:This study was a part of a M.S. thesis and a research project funded by deputy of research, Kashan university of medical sciences with the grant number of 9250. The registration ID in IRCT was IRCT2013042313102N.

References

- 1.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Marmot M. Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(18):6508–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delle Fave A, Brdar I, Freire T, Vella-Brodrick D, Wissing MP. The Eudaimonic and Hedonic Components of Happiness: Qualitative and Quantitative Findings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;100(2):185–207. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashdan TB, Biswas-Diener R, King LA. Reconsidering happiness: the costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. J Posit Psychol. 2008;3(4):219–33. doi: 10.1080/17439760802303044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–55. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diener E. The Science of Well-Being. Netherlands: Springer; 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehm JK, Lyubomirsky S. Does Happiness Promote Career Success? J Career Assess. 2008;16(1):101–16. doi: 10.1177/1069072707308140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Rev General Psych. 2005;9(2):111–31. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanthamongkolchai S, Tuntichaivanit C, Munsawaengsub C, Charupoonphol P. Factors influencing life happiness among elderly female in Rayong Province, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92 Suppl 7:S8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):925–71. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giordana JY, Roelandt JL, Porteaux C. [Mental Health of elderly people: The prevalence and representations of psychiatric disorders]. Encephale. 2010;36(3 Suppl):59–64. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(10)70018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. 10 facts on ageing and the life course. 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/ageing/en/index.html.

- 12.Stevens GA, Mathers CD, Beard JR. Global mortality trends and patterns in older women. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(9):630–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Mental health and older adults. 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs381/en/.

- 14.Abdi Zrin S, Akbarian M. Successful aging in the light of religion and Religious beliefs. Salmand Iran J Ageing. 2007;2(4):293–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivera J, Benabarre S, Lorente T, Rodriguez M, Pelegrin C, Calvo JM, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and mental disorders detected in primary care in an elderly Spanish population. The PSICOTARD Study: preliminary findings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):915–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Mental health. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/..

- 17.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002;287(2):203–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haller M, Hadler M. How Social Relations and Structures can Produce Happiness and Unhappiness: An International Comparative Analysis. Soc Indic Res. 2006;75(2):169–216. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-6297-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheibani Tezerji F, Pakdaman S. Effect of music therapy, reminiscence and performing enjoyable tasks on loneliness in the elderly. J Appl Psychol. 2010;4(15):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slade M. Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, Orrell M, Davies S. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson T, Stallard P, Velleman S. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for the prevention and treatment of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13(3):275–90. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467–87. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh HF, Wang JJ. Effect of reminiscence therapy on depression in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(4):335–45. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao SY, Liu HY, Wu CY, Jin SF, Chu TL, Huang TS, et al. The effects of group reminiscence therapy on depression, self esteem, and life satisfaction of elderly nursing home residents. J Nurs Res. 2006;14(1):36–45. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000387560.03823.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen TJ, Li HJ, Li J. The effects of reminiscence therapy on depressive symptoms of Chinese elderly: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ando M, Morita T. Efficacy of the structured life review and the short-term life review on the spiritual well-beingof terminally ill cancer patients. Health. 2010;02(04):342–6. doi: 10.4236/health.2010.24051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stinson CK, Kirk E. Structured reminiscence: an intervention to decrease depression and increase self-transcendence in older women. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(2):208–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin YC, Dai YT, Hwang SL. The effect of reminiscence on the elderly population: a systematic review. Public Health Nurs. 2003;20(4):297–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JJ. The effects of reminiscence on depressive symptoms and mood status of older institutionalized adults in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(1):57–62. doi: 10.1002/gps.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):645–57. doi: 10.1080/13607860701529635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou YC, Lan YH, Chao SY. [Application of individual reminiscence therapy to decrease anxiety in an elderly woman with dementia]. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2008;55(4):105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cappeliez P, Rivard V, Guindon S. Functions of reminiscence in later life: proposition of a model and applications. Eur Rev Appl Psych. 2007;57(3):151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2005.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, Smit F. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):291–300. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majzoobi MR, Momeni K, Amani R, Hojjat KM. The Effectiveness of Structured Group Reminiscence on The Enhancement of the Elderly’s Life Quality And Happiness. J Iran Psychol. 2013;9(34):189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Momeni K. Memory processing narrative coherence and effectiveness in reducing depressive symptoms in elderly women living in sanitarium. J Counsel Fam Ther. 2012;1(3):366–81. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willemse BM, Depla MF, Bohlmeijer ET. A creative reminiscence program for older adults with severe mental disorders: results of a pilot evaluation. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(5):736–43. doi: 10.1080/13607860902860946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiang KJ, Chu H, Chang HJ, Chung MH, Chen CH, Chiou HY, et al. The effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological well-being, depression, and loneliness among the institutionalized aged. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):380–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foroughan M, Jafari Z, Shirin BP, Ghaem Magham FZ, Rahgozar M. Validation of mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in the elderly population of Tehran. Adv Cogn Sci. 2008;10(2):29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin LC, Watson R, Lee YC, Chou YC, Wu SC. Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia (EdFED) scale: cross-cultural validation of the Chinese version. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):116–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghasemi A, Abedi A. Effectiveness of group education based on expectancy theory Snyder on elderly Happiness. Knowledge Res Psych Islamic Azad Univ. 2010;41:17–44. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alipoor A, Noorbala A. A preliminary evaluation of the validity and reliability of the Oxford happiness questionnaire in students in the universities of Tehran. Iran J of Psych and Clinical Psych (Andeesheh Va Raftar). 1999;5(18-17):55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watt LM, Cappeliez P. Integrative and instrumental reminiscence therapies for depression in older adults: Intervention strategies and treatment effectiveness. Aging Ment Health. 2000;4(2):166–77. doi: 10.1080/13607860050008691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinquart M, Forstmeier S. Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(5):541–58. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.651434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ, Emmerik-de Jong M. The effects of integrative reminiscence on meaning in life: results of a quasi-experimental study. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(5):639–46. doi: 10.1080/13607860802343209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arkoff A, Meredith GM, Dubanoski JP. Gains in Well-Being Achieved Through Retrospective-Proactive Life Review By Independent Older Women. J Human Psych. 2004;44(2):204–14. doi: 10.1177/0022167804263065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karimi H, Dolatshahee B, Momeni K, Khodabakhshi A, Rezaei M, Kamrani AA. Effectiveness of integrative and instrumental reminiscence therapies on depression symptoms reduction in institutionalized older adults: an empirical study. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(7):881–7. doi: 10.1080/13607861003801037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cappeliez P, Guindon M, Robitaille A. Functions of reminiscence and emotional regulation among older adults. J Aging Stud. 2008;22(3):266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gudex C, Horsted C, Jensen AM, Kjer M, Sorensen J. Consequences from use of reminiscence--a randomised intervention study in ten Danish nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryant FB, Smart CM, King SP. Using the Past to Enhance the Present: Boosting Happiness Through Positive Reminiscence. J Happiness Stud. 2005;6(3):227–60. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3889-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]