Abstract

Objective

To validate the reliability and efficiency of alternative cutoff values on the abbreviated six-item post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Checklist (PCL-6) (Lang & Stein, 2005) for underserved, largely minority patients in primary care settings of Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs).

Method

Using a sample of 760 patients recruited from six FQHCs in the New York City and New Jersey metropolitan area from June 2010 to April 2013, we compared the PCL-6 with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for DSM-IV. We used reliability statistics for single cutoff values on PCL-6 scores. We examined the relationship between probabilities of meeting CAPS diagnostic criteria and PCL-6 scores by nonparametric regression.

Results

PCL-6 scores range between 6 and 30. Reliability and efficiency statistics for cutoff between 12 and 26 were reported. There is a strong monotonic relationship between PCL-6 scores and the probability of meeting CAPS diagnostic criteria.

Conclusion

No single cutoff on PCL-6 scores has acceptable reliability on both false positive and false negative simultaneously. An ordinal decision rule (low risk: 12 or less, medium risk: 13 to 16, high risk: 17 to 25, and very high risk: 26 and above) can differentiate the risk of PTSD. A single cutoff (17 or higher as positive) may be suitable for identifying those with the greatest need for care given limited mental health capacity in FQHC settings.

Keywords: PTSD, PCL-6, screening, validation, integrating mental health and primary care, practice-based research networks (PBRNs)

1. Introduction

An important component of implementing primary care interventions for PTSD is the development of validated, reliable, and efficient brief screening instruments that can be used by a range of staff in different clinical settings. Time constraints and the under-identification of patients who are at risk for PTSD are key barriers to facilitating mental health treatment in primary care (Meredith et al., 2009). Although a number of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) screening instruments have been created and tested (Breslau, Peterson, Kessler, & Schultz, 1999; Lang & Stein, 2005; Prins et al., 2004), none has been validated for underserved multi-ethnic and low-income populations, such as those served by Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) (USDHHS, 2011).

FQHCs are in a prime position to facilitate access to needed mental health treatment given the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in primary care settings (Ansseau et al., 2004; Sansone & Sansone, 2010). It is estimated that up to 30% of primary care patients have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, most commonly mood or anxiety disorders (Sansone & Sansone, 2010). Estimates of the prevalence of PTSD in primary care settings have ranged between 9% and 23% (Gillock, Zayfert, Hegel, & Ferguson, 2005; Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan, & Löwe, 2007; Liebschutz et al., 2007; Magruder et al., 2005; Neria et al., 2006; Stein, McQuaid, Pedrelli, Lenox, & McCahill, 2000; Taubman-Ben-Ari, Rabinowitz, Feldman, & Vaturi, 2001). Although one study indicates that nearly 90% of FQHCs routinely screen for depression (Lardiere, Jones, & Perez, 2011), primary care clinicians in FQHCs tend not to screen for PTSD (Meredith et al., 2009). A potential way to promote screening for PTSD by primary care clinicians in FQHCs would be to have a brief screener that is reliable and efficient for use in those settings.

Thus, the purpose of this study is to validate a brief PTSD screening instrument, the abbreviated six-item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-6) (Lang & Stein, 2005) with a sample of underserved, largely minority patients recruited from FQHCs and to investigate the reliability and efficiency of screening decision rules. The PCL-6 is a subset of the original PCL, where two items which had the highest correlation with the symptom cluster score were selected from each of the three symptom clusters. The six items in PCL-6 are: 1) cluster B: memories, thoughts or images, upset when reminded; 2) cluster C: avoid activities or situations; feeling distance or cutoff; 3) cluster D: irritable or angry; difficulty concentrating. PCL scores range between 6 and 30. The reliability of PCL-6 had been previously examined among military veteran populations (Lang & Stein, 2005). In a subsequent study, Lang et al. (2012) investigated the utility of the PCL-6 to measure treatment-related symptom changes among PTSD patients in primary care settings. However, the screening performance of the PCL-6 in civilian primary care settings, particularly in FQHCs with predominantly underserved patients, has not been explored. Furthermore, examining various cut-off scores for the PCL-6 is also needed so that the use of a brief PTSD screener can be appropriately calibrated according to the differing needs of FQHCs (e.g., maximizing efficiency, adjusting to center resources).

2. Material and methods

2.1 Setting

This study was conducted in seven FQHCs across the New York City and New Jersey metropolitan area from May 2011 to April 2013. These FQHCs were members of Clinical Directors Network (CDN – www.CDNework.org), an establisshed practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) that works with FQHCs. This study was part of a parent study, which tested in a randomized controlled trial a primary care collaborative care intervention for PTSD. For additional details of the parent study see Meredith et al. (2014) and Meredith; et al. (2015).

2.2 Participants and Procedures

Study procedures were approved by IRBs in the organizations of all authors. Participants were approached in the waiting rooms of the FQHCs and assessed for study eligibility. Eligible participants had to receive care from a Primary Care Clinician, be either English or Spanish speaking, between the ages of 18 to 65 years old, and able to provide informed consent. A total of 760 participants with a history of trauma were included in this study by a case-control design, where 595 patients scored 14 or more points on the PCL-6 (cases) were recruited by a parent study of PTSD intervention (Meredith; et al., 2015), and 165 additional participants scored less than 14 points (controls) were recruited to supplement the parent study. The sample size for case patients was determined by the parent study for detecting a medium standardized effect size for the intervention of the parent study. The additional sample size for control patients was based on another power calculation to ensure the accuracy of estimating the statistical reliability measure (the 1-sample z-type 95% confidence interval for a proportion will be no wider than 0.16). All power calculations were conducted in the computing environment R.

Protocol and procedure of recruiting case patients were reported in Meredith et al. (2014). Recruitments for the control patients followed the same protocol. In total, 8,422 patients in the seven participating FQHCs were approached in the parent study. Among all patients we approached, 4,863 passed eligibility criteria and agreed to take the PCL-6 screener by a recruitment coordinator in the waiting room, where 965 were considered as at risk in the parent study (scored 14 points or higher on PCL-6). A part of the at-risk patients (62%, n = 595) further agreed to take the CAPS.

Following the administration of the PCL-6, research assistants administered the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for DSM-IV (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1994). All research assistants had a bachelor's or master's level degree, had experience in conducting practice-based research studies, and were trained to administer CAPS for DSM-IV. A subsample of the CAPS interviews (15%) were audio recorded and co-ratings by a clinical psychologist and doctoral student in clinical psychology indicated a high reliability (efficiency = 0.92, correlation =0.93, Cohan's Kappa =0.79). Among the 760 participants, 51.8% (394) met the CAPS diagnosis criteria.

2.3. Measures

The PCL-6 contains six items from the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Civilian Version, a 17-item self-report measure that is keyed to the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD (Weathers et al., 1994). The dichotomous diagnosis from the CAPS structured diagnostic interview (Blake et al., 1995; Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001) was used as the “gold standard.” The CAPS has been established as a psychometrically sound, reliable, and valid measure of PTSD diagnosis and a useful and sensitive indicator of clinical change (Weathers et al., 2001).

2.4. Analyses

We first conducted a categorical data analysis between the diagnostic status established by the CAPS and single cutoff values based on the total sum score of the PCL-6. We define the true positive (TP), the false positive (FP), the true negative (TN), and the false negative (FN). The positive/negative conditions are based on the PCL-6 cutoff and the true/false conditions are based on the CAPS diagnosis. For example, a true positive case is a patient who scored higher than the cutoff on the PCL-6 and met the diagnostic criteria in CAPS.

For each potential cutoff value between 6 and 30 on the PCL-6 scores, we estimated the standard reliability and efficiency measures (Kraemer, 1992): positive predictive value (PPV) = TP / (TP + FP), negative predictive value (NPV) = TN / (TN + FN), sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN), specificity = TN / (TN + FP), and efficiency = (TP + TN) / N, where N is the total sample size, as well as the 95% confidence intervals. To further remove estimation errors among adjacent cutoff values, we fitted smooth nonparametric regression of the reliability measures versus the cutoff values. We performed the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and calculated the area under curve (AUC).

Next, we estimated the probabilities of positive CAPS diagnosis versus the PCL-6 scores. For simplicity in presentation, we denote the conditional probability of positive CAPS given a PCL-6 score as P(PTSD) hereafter. We estimated P(PTSD) at each observed level of PCL-6 scores by one-sample proportion estimates: for a given PCL-6 score value, we subset the patients with the corresponding PCL-6 score, and calculated the sample proportion for those with positive CAPS diagnosis.

Given that the sample size at each distinct PCL-6 score was small, we fitted a nonparametric generalized additive model (GAM) (Hastie, Tibshirani, Friedman, & Franklin, 2005) to estimate a smooth relationship between P(PTSD) and PCL-6 scores. Based on the relationship between P(PTSD) and the PCL-6 scores, we investigated an ordinal screening decision rule using multiple cutoff values. We considered a p-value of 0.05 (two-tailed) to be significant.

3. Results

The mean PCL-6 score in the study sample was 18.3 (SD = 6.5, range 6 – 30). The mean CAPS severity score was 49.4 (SD = 27.7, range 0 – 114). Among the 760 participants, 394 met the diagnostic criteria in CAPS. Table 1 lists detailed descriptive statistics of PCL-6 scores, CAPS severity scores, and CAPS diagnosis by gender, race/ethnicity, and age group. A greater proportion of female participants had a PTSD diagnosis than males. Similarly, rates of PTSD diagnoses were greater among Hispanic participants than other non-Hispanic race groups combined. Older participants (34 and above) had notably higher percentages of positive PTSD diagnosis than younger participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample (N=760)a.

| CAPS diagnosis status | PCL-6 score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n=366) | Positive (n=394) | <14 (n=165) | ≥14 (=595) | |

| % female | 73.0 | 80.7 | 67.3 | 79.3 |

| % Hispanic (of any race) | 42.4 | 55.6 | 40.6 | 51.5 |

| % non-Hispanic black | 47.5 | 33.8 | 50.3 | 38.2 |

| % non-Hispanic white | 3.6 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 4.9 |

| % non-Hispanic other races | 6.0 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 4.9 |

| Average age (SD) | 39.0 (13.2) | 42.2 (12.1) | 38.0 (13.5) | 41.4 (12.4) |

| Average CAPS severity score (SD) | 24.4 (15.4) | 70.6 (15.4) | 15.1 (16.3) | 57.4 (23.4) |

| Average PCL-6 score (SD) | 14.7 (6.0) | 21.6 (5.0) | 9.1 (2.4) | 20.9 (4.7) |

Some participants were not included in calculating subgroup descriptive statistics due to their nonresponse to demographic questions: 11 participants refused to report race/ethnicity and 6 refused to provide age information.

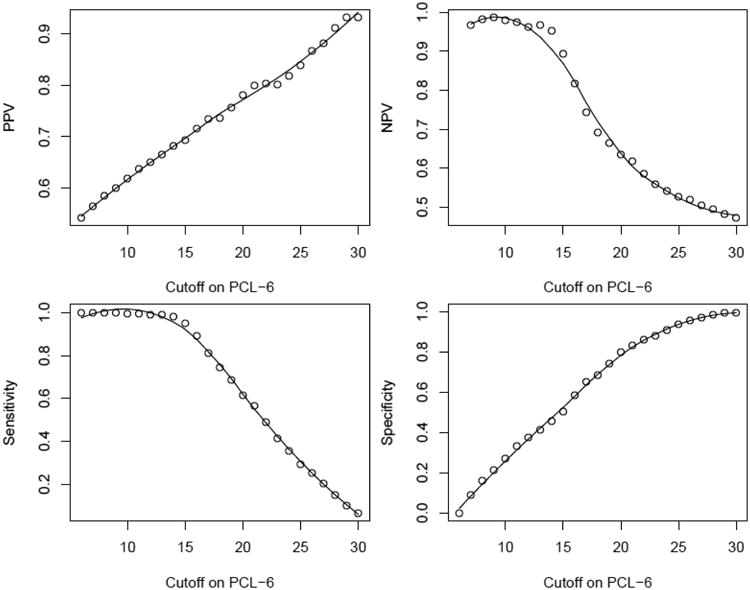

Table 2 presents the statistical reliability measures for a dichotomous screening rule using a single cutoff value between 12 and 26 points on the PCL-6. Cutoff values of 15 points and lower all have high NPV (>0.90), but a cutoff value has to be 24 points or higher to yield a moderately high PPV (>0.80). On the other hand, cutoff values of 16 points or lower all give high sensitivity (>0.89), but a moderately high specificity (0.81) is achieved with a cutoff value of 21 points. Efficiencies are always significantly lower than 0.80. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is 0.80. Figure 1 plots the nonparametric fit of reliability measures versus cutoff values.

Table 2. Reliability and efficiency statistics and 95% confidence intervals for selected cutoff values in PCL-6 (positive screening results defined as scores ≥ cutoff).

| PCL-6 Cutoff | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 0.62 (±0.04) | 0.96 (±0.03) | 0.99 (±0.01) | 0.35 (±0.05) | 0.68 (±.03) |

| 13 | 0.63 (±0.04) | 0.97 (±0.03) | 0.99 (±0.01) | 0.39 (±0.05) | 0.70 (±0.03) |

| 14 | 0.65 (±0.04) | 0.95 (±0.03) | 0.98 (±0.01) | 0.43 (±0.05) | 0.71 (±0.03) |

| 15 | 0.66 (±0.04) | 0.91 (±0.04) | 0.95 (±0.02) | 0.48 (±0.05) | 0.73 (±0.03) |

| 16 | 0.69 (±0.04) | 0.83 (±0.05) | 0.89 (±0.03) | 0.56 (±0.05) | 0.73 (±0.03) |

| 17 | 0.70 (±0.04) | 0.76 (±0.05) | 0.81 (±0.04) | 0.63 (±0.05) | 0.72 (±0.03) |

| 18 | 0.71 (±0.04) | 0.71 (±0.05) | 0.75 (±0.04) | 0.67 (±0.05) | 0.71 (±0.03) |

| 19 | 0.73 (±0.05) | 0.69 (±0.05) | 0.70 (±0.04) | 0.73 (±0.05) | 0.71 (±0.03) |

| 20 | 0.75 (±0.05) | 0.66 (±0.04) | 0.62 (±0.05) | 0.78 (±0.04) | 0.70 (±0.03) |

| 21 | 0.77 (±0.05) | 0.64 (±0.04) | 0.57 (±0.05) | 0.81 (±0.04) | 0.69 (±0.03) |

| 23 | 0.77 (±0.05) | 0.61 (±0.04) | 0.50 (±0.05) | 0.84 (±0.04) | 0.66 (±0.03) |

| 24 | 0.78 (±.006) | 0.58 (±0.04) | 0.42 (±0.05) | 0.87 (±0.04) | 0.64 (±0.03) |

| 25 | 0.81 (±0.06) | 0.57 (±0.04) | 0.37 (±0.05) | 0.90 (±0.03) | 0.63 (±0.03) |

| 26 | 0.84 (±0.06) | 0.56 (±0.04) | 0.31 (±0.04) | 0.93 (±0.03) | 0.61 (±0.03) |

Figure 1.

Plot of reliability measures of the PCL-6: PPV (upper left), NPV (upper right), sensitivity (lower left), and specificity (lower right). Circles are the raw estimates and curves are smoothing regression fit.

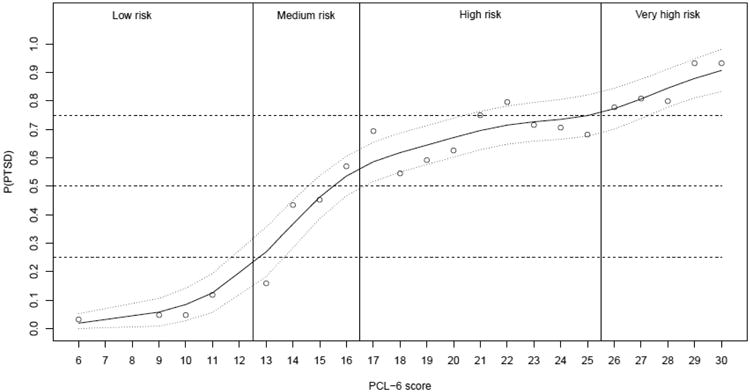

Figure 2 presents the estimated P(PTSD) from the one-sample procedures and the GAM fit. These results confirmed that PCL-6 scores can be used as a numeric measure for the likelihood of a positive PTSD diagnosis. According to the GAM fit, P(PTSD) has a sharp incline between 13 and 16 points on the PCL-6, then increases slowly and between 17 and 25 points on the PCL-6, and resumes a relatively fast increase after 25 points on the PCL-6. Based on these observations, the full range of PCL-6 scores can be cut into four areas. Specifically, the area of 12 points and below has low risk of meeting CAPS diagnostic criteria (P(PTSD)<0.20, odds<0.25). The area between 13 and 16 points is associated with an increased risk (0.25 < P(PTSD) < 0.55, 0.33 < odds < 1.22). The PTSD risk in this area is generally relevant, but P(PTSD) does not significantly exceed 0.5. The next area between 17 and 25 points has high risk where P(PTSD) is significantly above 0.5 (0.58 < P(PTSD) < 0.75, 1.38 < odds < 3), and the risk increases slowly in this relatively wide range. The last area of 26 points and higher has very high risk (P(PTSD) > 0.77, odds > 3.3). Most patients in the last area meet the CAPS diagnostic criteria.

Figure 2.

Plot of probabilities of meeting PTSD diagnostic criteria in CAPS versus PCL-6 scores. Circles are the raw estimates by one-sample procedures. Solid and dotted curves are smoothing estimates and the 95% confidence band by GAM. The four risk categories are separated by vertical bars.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that the PCL-6 is a potentially useful PTSD screening tool for low-income, underserved minority populations who receive care in FQHCs and similar primary care practice settings. A good screening instrument should be able to detect most patients with the targeted condition and allow for a reasonably small number of false positives. For a dichotomous screening rule based on a single screener cutoff point on the PCL-6, we expect high NPV and sensitivity, and acceptable PPV and specificity. According to these criteria, the single cutoff of 14 points on the PCL-6 appears to be acceptable for clinical practice, particularly when the screening instrument needs to ensure that most patients with a PTSD diagnosis are detected. The cutoff of 14 points on the PCL-6 had been established as the optimal cutoff among patients in VA primary care clinics (Lang & Stein, 2005).

Our study further confirmed that the PCL-6 has sufficient validity (in terms of sensitivity) as a screener for PTSD. However, primary care settings with limited resources, such as many FQHCs, may not be willing to implement a screening tool with low PPV and specificity (i.e., a high proportion of false positive cases among those screened positive and a large number of false positive cases, respectively). While the existing cutoff of 14 points is good at identifying negative cases, it is inefficient in identifying positive cases. In this study, roughly one third of patients who screened 14 points or higher (209 of 595) did not meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Given the results in Figure 1 and Table 2, it is difficult to find a single best cutoff value with high efficiency for clinical reference if resource limitations are of concern.

Nevertheless, the monotonic relationship between PCL-6 scores and P(PTSD) in Figure 2 is a valuable reference for clinical practice. Instead of a single cutoff, an ordinal screening rule may consist of several risk categories in the PCL-6 scores. We propose a decision rule with four risk categories based on PCL-6 scores: low risk (12 points or less), medium risk (13 to 16 points), high risk (17 to 25 points), and very high risk (26 points and above). These categories are marked by vertical bars in Figure 2. If a single cutoff must be employed, our analyses indicate that the cut-off value of 17 points i.e., between the high and medium risk categories) is optimal for identifying those with the most need for care given limited capacity. This is higher than is typically used in veteran and other civilian populations (14 points).

Our study had a number of limitations. First, due to the limited resources and relatively small sample, we did not have a second validation sample to further verify the reliability measures of the recommended cutoff values. Further validations and refinements, perhaps through large-scale retrospective studies, are needed to continue improving the various PTSD screening tools including PCL-6. The current study serves as one of such steps. Second, the PCL-6, while shorter than the full-length PCL and has acceptable reliability, may still be too resource demanding to be applied in a primary care setting. Lang and Stein (2005) discussed other shorter forms of PCL screener (two-, three-, and four-item versions) which also have very good sensitivity but low specificity. For example, the two-item PCL (with a cutoff of 4 points) had a sensitivity of .96 and a specificity of 0.58. Given the relatively low prevalence rate of PTSD in the civilian population, the low specificity of a screener will result in a large number of false positives which in turn may require unnecessary actions from both patients and providers. In the long run, the shorter screener may be more expensive for the health care system than a slightly longer 6-item screener with better reliability. When specificity is a lesser concern, these short forms of PCL may be preferred to PCL-6 in clinical practice for their easier implementation. In this paper we did not intend to compare among different abbreviated forms of PCL. Third, we did not use the most advanced statistical estimation techniques due to our limited capability. We did not use the bootstrapping procedure for the ROC analysis.

5. Conclusion

With the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), it is anticipated that FQHCs may be serving up to 40 million patients by 2015 (Lardiere et al., 2011). The role of FQHCs in providing integrated primary care and mental health care to this population is likely to expand under health care reform but there are a number of barriers that will make it difficult for FQHCs to meet the needs of all patients. The PCL-6 can be a useful and cost-effective instrument for screening PTSD in the primary care setting. The PCL-6 takes little time to administer and may be feasible for use in primary care settings with busy clinicians. A higher cutoff of 17 points on the PCL-6 is more suitable for identifying those with the most need for care when resources are limited, although it can lead to slightly more false negative cases. An ordinal decision rule based on multiple cutoff values can further differentiate the risk of PTSD from low to very high, which may provide FQHCs with useful information when deciding on the optimal cutoff points for their particular setting.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a supplemental grant (R01MH082768-02S1) of the parent grant to Dr. Meredith from the National Institute of Mental Health/NIMH (R01MH082768). The authors thank the following Community Health Centers for partnering on the study: Morris Heights Health Center, Bronx, NY, Joseph P. Addabbo Health Center – Main Site, Far Rockaway, NY, Joseph P. Addabbo Health Center – Central Avenue, Far Rockaway, NY, Ryan NENA Health Center, NY, NY, Soundview Health Center, Bronx, NY, Open Door Family Health Center, Port Chester, NY, Metropolitan Family Health Network, Jersey City, NJ. We also thank CDN staff, including: Marleny Diaz-Gloster, MPH Tzyy Jye Lin, MPH, Rosario Hinojosa, Jennifer Rodriguez, Tatiana Carillo, Mala Nimalasuriya, Carrie Goodman, MPH, Carmen Rodriguez, Ajeenah Haynes, PhD, Parisa Faysar, Elizabeth Leonard, Omesh Persaud, and Taralah Washington for their assistance in identifying, recruiting, interviewing, translating, patient care management and translating materials from patient research participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ansseau M, Dierick M, Buntinkx F, Cnockaert P, De Smedt J, Van Den Haute M, Vander Mijnsbrugge D. High prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Kessler RC, Schultz LR. Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(6):908–911. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillock KL, Zayfert C, Hegel MT, Ferguson RJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care: prevalence and relationships with physical symptoms and medical utilization. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27(6):392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J, Franklin J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference and prediction. The Mathematical Intelligencer. 2005;27(2):83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC. Evaluating medical tests: Objective and quantitative guidelines. Sage publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenk K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mohanan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;146(5):317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Stein MB. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behaviour research and therapy. 2005;43(5):585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Wilkins K, Roy-Byrne PP, Golinelli D, Chavira D, Sherbourne C, et al. Craske MG. Abbreviated PTSD Checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2012;34(4):332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere M, Jones E, Perez M. National Association of Community Health Centers 2010 assessment of behavioral health services provided in federally qualified health centers. Bethesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liebschutz J, Saitz R, Brower V, Keane TM, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Averbuch T, Samet JH. PTSD in urban primary care: high prevalence and low physician recognition. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22(6):719–726. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Davis L, Hamner MB, Martin RH, et al. Arana GW. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27(3):169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Green BL, Basurto-Dávila R, Cassells A, Tobin J. System factors affect the recognition and management of post-traumatic stress disorder by primary care clinicians. Medical care. 2009;47(6):686. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190db5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Green BL, Kaltman S, Wong EC, Han B, et al. Tobin JN. Design of the Violence and Stress Assessment (ViStA) study: A randomized controlled trial of care management for PTSD among predominantly Latino patients in safety net health centers. Contemporary clinical trials. 2014;38(2):163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Han B, Green Bonnie L, Kaltman S, Wong EC, et al. Tobin JN. Impact of the Violence and Stress Assessment (ViStA) Program to Improve PTSD Management in Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. 2015 Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Wickramaratne P, Das A, et al. Marshall RD. Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care one year after the 9/11 attacks. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(3):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. Sheikh JI. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2004;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Psychiatric disorders: a global look at facts and figures. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2010;7(12):16–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2000;22(4):261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00080-3. doi: http://dx.oi.org/10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubman-Ben-Ari O, Rabinowitz J, Feldman D, Vaturi R. Post-traumatic stress disorder in primary-care settings: prevalence and physicians' detection. Psychological medicine. 2001;31(3):555–560. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. Health Center, State, and National Data - Special Tabulation. 2011 Retrieved 9/9/2013 http://bphc.hrsa.gov/healthcenterdatastatistics/index.html.

- Weathers F, Keane T, Davidson J. Clinical-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and anxiety. 2001;13(3):132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T. The PTSD checklist-civilian version (PCL-C) Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD; 1994. [Google Scholar]