Abstract

Engineered heart tissue has emerged as a personalized platform for drug screening. With the advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, patient-specific stem cells can be developed and expanded into an indefinite source of cells. Subsequent developments in cardiovascular biology have led to efficient differentiation of cardiomyocytes, the force-producing cells of the heart. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) have provided potentially limitless quantities of well-characterized, healthy, and disease-specific CMs, which in turn has enabled and driven the generation and scale-up of human physiological and disease-relevant engineered heart tissues. The combined technologies of engineered heart tissue and iPSC-CMs are being used to study diseases and to test drugs, and in the process, have advanced the field of cardiovascular tissue engineering into the field of precision medicine. In this review, we will discuss current developments in engineered heart tissue, including iPSC-CMs as a novel cell source. We examine new research directions that have improved the function of engineered heart tissue by using mechanical or electrical conditioning or the incorporation of non-cardiomyocyte stromal cells. Finally, we discuss how engineered heart tissue can evolve into a powerful tool for therapeutic drug testing.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, disease modeling, drug screening, induced pluripotent stem cells, tissue engineering

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1 Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States [1]. Cardiomyopathies are a prevalent and serious class of CVD in which the contractile strength of the heart is compromised. Furthermore, although patients may present with similar symptoms, and hence are classified as suffering from a single disease, their underlying disease mechanisms are not uniform. Due to the variability in disease mechanisms, medications and dosages may vary among patients, making it difficult for caregivers to provide universally efficacious treatment, thus creating a tremendous burden on the healthcare system. Furthermore, the development of a new drug is expensive and inefficient, requiring on average over a decade of research and development and ~$5 billion per drug [2-6].

1.2 Drugs withdrawn from the market due to cardiac toxicity

Withdrawal of drugs from the market due to previously unobserved toxic effects in animals (or false negatives), which have been attributed to off- and on-target toxicity including cardiotoxicity, is an unfortunate reality [7-10]. As examples, Terfenadine (trade name Seldane) was withdrawn in 1998 for inducing cardiac arrhythmias; Grepafloxacin (trade name Raxar) was withdrawn in 1999 for prolonging the QT interval; Rofecoxib (trade name Vioxx, Ceoxx, and Ceeoxx) was withdrawn in 2004 for the risk of myocardial infarction; and Rosiglitazone (trade name Avandia) suffered from a drastic decrease of sales due to reports of increased risk of heart attack [3, 9]. Typically, drug safety and efficacy are evaluated using non-human animal models followed by costly clinical trials. Human models are difficult to establish because human heart cells or tissue from patients cannot survive long-term culture [11] and are difficult to obtain [12, 13]. The existing preclinical testing paradigm relies heavily on the use of in vitro cell lines such as Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells overexpressing the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) channels, ex vivo tissue preparations such as isolated arterially perfused left ventricular rabbit wedge preparations, and in vivo studies such as chronic dog atrioventricular (AV) block models [10]. However, there are several challenges with these models, including their high costs and their poor predictive capacity owing to inter-species differences in cardiac electrophysiology and human biology[14, 15]. In addition, CHO and HEK293 cells are not ideal models for cardiotoxicity because ectopic expression of a cardiac ion channel does not always recapitulate function in human cardiomyocytes [16]. Models with poor predictive power lead to a high probability of discarding new chemical entities (due to false positives) that otherwise might have become safe and effective drugs. Hence, there is a need for immediate attention from all stakeholders involved in the drug discovery process to address these concerns and to better evaluate drugs before clinical trials.

1.3 Induced pluripotent stem cells for disease models

A new approach towards reducing inefficacious drug treatment is precision medicine, and this endeavor is increasingly feasible with the advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [17, 18]. Unlike other cells, iPSCs reflect a person's unique genotype because they are derived from a patient's somatic cells (e.g., peripheral blood mononuclear cells or skin fibroblasts). They have the capacity to differentiate into all cell types, including cardiomyocytes (CMs), the force-producing cells of the heart [19, 20]. Patient- and disease-specific models are being developed to provide unprecedented multi-dimensional information on the individual's disease and a system to evaluate innovative therapeutic options.

Patients carrying known mutations for a disease are able to contribute to the generation of disease-specific iPSC lines. For example, some of the first iPSC-derived cellular models were developed for LEOPARD syndrome [21], long QT [22, 23], familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) [24], familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) [25], Timothy syndrome [26], and aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 genetic polymorphism [27]. Channelopathies, caused by specific mutations in cardiac ion channels, can also be modeled using iPSC-CMs. One example is long QT syndrome, which is characterized by prolonged ventricular repolarization that can lead to sudden cardiac death [28, 29] and is caused by mutations in potassium channels [30].

The quality of the disease model can be determined by the disease phenotype of the iPSC-CM as compared to the physiological disease phenotype. For example, DCM iPSC-CMs carrying the TNNT2 mutation [31] displayed disorganized sarcomeric structures, abnormal calcium handling, and decreased contractile function similar to the cardiomyocyte phenotype in DCM patients. Likewise, iPSC-CMs from patients with an HCM mutation in the myofilament myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7) [25] recapitulated phenotypic features of abnormal calcium handling, increased myofibril content, and cellular hypertrophy at baseline and upon stress [25].

A disease model must also recapitulate physiological drug response in order to accurately evaluate drugs before treatment administration. For example, iPSC-CMs derived from DCM patients respond to β agonists and β blockers in a similar manner to patients. It is important to understand patient-specific β blocker response because although β1-specific adrenergic blockers are beneficial to patients with DCM [32, 33], the use of β-adrenergic agonists can lead to increased morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure [34]. Upon exacerbation by β-adrenergic agonists such as norepinephrine (a drug which physiologically activates the fight-or-flight response and increases heart rate), the DCM iPSC-CM model recapitulates the DCM phenotype [31]. After adding the β-blocker metoprolol, the phenotype was rescued, recapitulating results from previous β-blocker trials [32, 33]. In a recent mechanistic study using the DCM iPSC-CM model, a mechanism of compromised β-adrenergic signaling was identified as nuclear localization of mutant TNNT2 and epigenetic regulation of phosphodiesterases 2A and 3A [35].

In another example, iPSC-CMs with long QT mutations had a similar drug response as patients with long QT. Arrhythmias were induced upon treatment with β-adrenergic stimulants and arrhythmias were rescued upon subsequent addition of β blockers [22, 36]. In a drug response study, an iPSC-CM model derived from long QT patients showed shortened repolarization upon treatment with the experimental potassium channel enhancers nicorandil and PD118057 [36]. Based on these results, the use of potassium channel enhancers might be considered in patients with long QT.

1.4 Human iPSC-CMs as compared to neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes

The quality of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) is determined by the maturity of their structure and function as compared to human neonatal or adult cardiomyocytes (Fig 1). (The same criteria also apply to human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, or ESC-CMs). It is well known that independent of cell line or reprogramming and cardiac differentiation methods, the resultant iPSC-CMs possess gene expression, structural, and functional properties that resemble the human fetal CM phenotype more than adult CMs [37-41]. For example, iPSC-CMs display expression of genes implicated in the mechanical and electrophysiological manifestation of cardiac contraction, including MYL2, MYH7, TNNI3, SCN5A, and KCNH2. The expression of sarcomeric protein MYH6 approaches adult levels, whereas the expressions of MYL7, MYH7, and TNNI3 are relatively less in iPSC-CMs compared to both fetal and adult cardiomyocytes [38, 42-44]. Structurally, iPSC-CMs are smaller in size and have irregular shapes (round/oval rather than rod-like shapes) compared to adult human cardiomyocytes [40, 45]. In addition, iPSC-CMs show unorganized sarcomeres, and the absence of T-tubules results in much slower excitation-contraction coupling [24, 39, 46].

Fig 1. Maturation and assessment of stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes.

Many strategies have been reported for the maturation of cardiomyocytes. In the biochemical approach, growth hormones or adrenergic agonists are added to promote a change in cardiomyocyte function. With molecular biology approaches, cardiac specific ion channels and microRNA are overexpressed to elicit changes in the electrophysiology and calcium handling of cardiomyocytes. Bioengineering approaches have also been shown to improve sarcomeric organization and contractile function by incorporating controlled parameters of substrate stiffness, topography, electrical/mechanical conditioning, and integrated systems that improve nutrient delivery. Assessment of function ranges from examining morphology (i.e., cell shape/size, sarcomeres, T-tubules, and alignment), to molecular assays (sarcomeric and ion channel expression), and functional assays (i.e., calcium transients, electromechanical coupling, contraction, electrophysiology, and tissue grafting).

The functional similarities and differences of iPSC-CMs to adult CMs also exist in the electrophysiological properties of the cells. These differences are used in assessing the maturation of the iPSC-CM (Fig 1). For instance, freshly dissociated human adult CMs are quiescent and beat or contract in response to stimuli [39], while ventricular- and atrial-like iPSC-CMs are autonomous and spontaneously beat which is due to adepolarized resting membrane potential. This increased automaticity of iPSC-CMs can be attributed to the presence of large funny currents (If) or pacemaker currents in addition to the under-expression of the inward rectifier potassium channel (IK1) consequentially leading to a large inward sodium current [39, 47]. Moreover, present cardiac differentiation methods produce a mixed population of ventricular-, atrial-, and nodal-like cells with ventricular-like CMs being the predominant cell type [16, 25, 48-54]. These three highly distinct subpopulations possess a spectrum of action potentials with varying features:;maximum diastolic potential (MDP, −57 to −75 mV); action potential amplitude, (APA, 87 to 113 mV); action potential duration at 90% repolarization (APD90, 173.5 ± 12.2 to 495 ± 36 ms); maximal upstroke velocity (dV/dtmax) (9 to 40 V/s); mean duration potential [22, 26, 54-56]. This heterogeneity corresponds to various stages of development and maturity as corroborated by single cell transcriptional profiling and is also suggestive of significant inter-cell line variability [39, 57]. However, this heterogeneity also represents a potential limitation in modeling cardiac diseases where a specific cardiomyocyte type is affected or in high-throughput drug screening.

Several studies have devised strategies to increase the maturity of iPSC-CMs, such as extended time in culture, overexpressing a deficient ion channel (e.g., IK1) [58] or cardiac specific microRNA (e.g., miR-1/miR-499 [59], let-7 [60]), pharmacological and neurohormonal treatment (e.g., adrenergic stimulation and triiodothyronine) [39], or electrical/mechanical conditioning (Fig 1). These approaches promise to significantly increase the overall maturity of iPSC-CMs. Further discussion of maturation strategies of iPSC-CMs using biochemical and molecular biology approaches is beyond the scope of this review, and interested readers are encouraged to refer to other reviews [29, 39, 41, 61].

1.5 iPSC-CMs for patient-specific 3D engineered heart tissue models

The ability to fabricate engineered heart tissue from diseased or healthy iPSC-CMs has led to its potential use as a tool in disease modeling, disease diagnosis with genotype-phenotype biomarkers, efficacy testing, cardiotoxicity and safety pharmacology, and the identification of disease-associated genes (Fig 2). The information learned from engineered heart tissues is foundational for future endeavors to create patient-specific heart tissue replicas for drug screening prior to treatment. Human iPSC-CMs can be utilized to fabricate 3D model structures that serve as models of cardiac tissue [62]. 3D models require a high number of cardiomyocytes, which is now more accessible with recent advances in robust and efficient cardiomyocyte differentiation protocols [17, 19, 20, 63]. With the increased availability of raw materials, the current challenge is to achieve physiologically relevant formation of engineered heart tissue.

Fig 2. Application of engineered heart tissue model.

Engineered heart tissue can be fabricated from diseased or healthy patient-specific iPSC-CMs. They are being utilized as models for various applications including modeling disease pathogenesis, disease diagnosis with genotype-phenotype biomarkers, pharmacological screening/efficacy testing, cardiotoxicity/safety pharmacology, and the identification of disease-associated genes.

2. Macrostructures of engineered heart tissue

2.1 Cardiomyocyte aggregates: the first engineered heart tissue

Primary cardiomyocytes cultured in aggregate demonstrate improved function compared to single cells [64]. By contrast, floating aggregates of cardiomyocytes are functionally more similar to intact heart tissue than 2D-monolayer cultures [65]. Collagen has become a standard hydrogel for 3D cardiomyocyte culture [64]. Building on work originally performed to prevent the detachment of skeletal myoblasts in culture [66], cardiomyocytes have been embedded in collagen I. The 3D environment of collagen improved tissue formation, inhibited dedifferentiation and overgrowth by non-cardiomyocytes, and allowed for the detection of contractile forces from multi-cellular samples [64, 67].

Following these studies, the format of engineered heart tissue has been evolving with the primary objective of improving electromechanical function (Table 1). The creativity displayed in the various designs of engineered heart tissue has led to increased functional readouts and a deeper understanding of engineered heart tissue formation and function.

Table 1.

Various formats of engineered heart tissue and their functional readouts

| Shape | Size | Cells | Scaffold | Supporting cells | Conditioning | Functional readout | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | 1.5 × 1.5 × 12 mm | NA | Native human left ventricle | None | None | Contractile force | Mulieri et al., 1992 |

| Band | 15 × 17 × 4 mm | Embryonic chick V-CM | Collagen | None | None | CM structure Contractile force |

Eschenhagen et al., 1997 |

| Ring | D/T 8-10 mm / 1 mm | Neonatal rat V-CM | Collagen | None | Passive stress | Contractile force In vivo engraftment |

Zimmermann et al, 2002 |

| Bioreactor | n/a | Neonatal rat V-CM | None | None | Turbulent flow | Metabolic activity Ultrastructure |

Carrier et al., 2002 |

| Bioreactor | D/T 1.1 mm / 1.5 mm | Neonatal rat V-CM | Collagen | None | Laminar flow | Cell viability | Radisic et al., 2003 |

| Band | 6 × 8 × 1.5 mm | Neonatal rat V-CM | Collagen | None | Electrical | CM structure Contractile properties |

Radisic et al., 2004 |

| Ring | D/T 15 mm/ 1-4 mm | Neonatal rat V-CM | Collagen | None | Passive stress |

In vivo grafting on infarcted hearts Electrical coupling |

Zimmermann et al., 2006 |

| Micro tissue | D/T: 100-200 μm / 3-4 mm | Neonatal rat V-CM | Collagen | Fibroblasts ECs |

Electrical | CM structure Electrophysiology |

Chiu et al., 2011 |

| Band | 20 mm × 0.5 mm | hESC-CM hiPSC-CM |

Collagen | Stromal (MEFs or HUVEC-ECs) | Mechanical (Static stress) | Contractile force In vivo graft survival Host vascularization |

Tulloch et al., 2011 |

| Micro tissue | D/L 100 μm / 500 μm | Neonatal rat V-CM | Collagen | None | Electrical | Contractile force Calcium dynamics |

Boudou et al., 2012 |

| Patch | 7 × 7 × 1.5 mm2 | hESC-CM | Fibrin | 45-90% CM purity | Unidirectional passive stress | Gene expression Electrophysiology Contractile force |

Zhang et al., 2013 |

| Biowire | 600 μm diameter | hESC-CM hiPSC-CM |

Collagen | None | Electrical | Structure Electrophysiology Calcium dynamics |

Nunes et al., 2014 |

| Patch | n/a | hiPSC-CM | Fibrin | ECs, SMCs | None | In vivo survival / integration | Ye et al., 2014 |

| Thin film | 95 μm × 13 μm | hiPSC-CM | None | None | None | CM Metabolism CM Structure Contractile force |

Wang et al., 2014 |

| MPS | 100-200 μm | hiPSC-CM | None | None | None | Drug response | Mathur et al., 2015 |

CM, cardiomyocytes; D, diameter, EC, endothelial cells; ESC, embryonic stem cell; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; MPS, microphysiological systems; NA, not applicable; SMC, smooth muscle cells; T, thickness, V, ventricular-type.

2.2 Stretch-induced contractility of engineered heart tissue

There is a critical relationship between cardiac tissue structure and contractile function. CMs interact via gap junctions, which facilitate the conduction of electrical signals [68, 69] and contractile forces [70]. Cell-cell interactions are important for the distribution of internal forces such as stretch, which occurs in the heart as a result of ventricular filling. Consequently, contractile forces are enhanced by passive forces experienced by the heart while under stretch [71-74]. This length-dependence of force generation, known as the Frank-Starling relationship [75-78], is evident in engineered heart tissue from native rat cardiomyocytes [79, 80] as well as stem cell-derived engineered heart tissue [73]. Total force per cross-sectional area generated by the tissue (stress) can be measured while the tissue is gradually stretched in fixed intervals (strain) [64]. This stress versus strain analysis yields a biomaterial property called the Young's modulus, which describes the stiffness of the tissue [81].

Macrostructures of engineered heart tissue that are matured under passive stretch increase strength of contraction (Table 2). One of the earliest macrostructures of engineered heart tissue that was developed under passive stretch was fabricated by Eschenhagen et al. using chick embryonic ventricular myocytes in a collagen hydrogel [64, 79]. The force of contraction of paced engineered heart tissue remained remarkably stable for up to 20 hours, unlike intact muscle preparations. In subsequent experiments, engineered heart muscle (EHM) was fabricated from native rat cardiomyocytes in collagen, resulting in 1 mm thick constructs [67, 74, 79, 82]. Their ring shape facilitated positioning onto two-pronged stretchers to allow for constant passive stress. They were visibly beating and produced 0.3 mN of force [80]. In a different report, the maximum static tension and total force were found to be similar at 0.4 mN and 0.48 mN [73]. For comparison, ex vivo rat heart tissue exerts 48.8 ± 5 mN in contractile force [83]. Cardiomyocyte alignment is also observed in stretch-induced engineered heart tissue [67, 73, 84, 85].

Table 2.

Contractile assessments of engineered heart tissue

| Cells | Cell Number | Size | Force Output |

Beat Rate | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Force | Contractile Force | Total Force | |||||

| Native rat ventricular heart tissue | ND | ND | ND | ND | 48.8 ± 5 mN/mm2 | n/a | Hibberd et al., 1982 |

| Native human left ventricular heart tissue | ND | 1.5 × 1.5 × 12 mm | ND | ND | 3.7 mN/mm2 22.8 mN/mm2 |

174 bpm 72 bpm |

Mulieri et al., 1992 |

| Embryonic Chick V-CM | 1 × 106 | 15×17×4mm (at seeding) | 1.15 ± 0.03 mN | 0.09 ± 0.006 mN to 0.2 ± 0.01 mN | ND | 72 bpm | Eschenhagen et al., 1997 |

| Neonatal rat V-CM | 1 × 106 | D/T 8-10mm/1 mm | 0.1-0.3 mN | 0.4 - 0.8 mN | 0.5-1.1 mN | ND | Zimmermann et al, 2002 |

| hESC-CM hiPSC-CM |

2 × 106 | 20mm × 0.5mm | 0.4 mN/mm2 | 0.08 mN/mm2 | 0.48 mN/mm2 | ND | Tulloch et al., 2011 |

| Neonatal rat V-CM | 500 | Micro tissue <100 μm thickness | 8.25 ± 0.61 μN | ND | ND | 66 bpm | Boudou et al., 2012 |

| hESC-CM | 1 × 106 | 7 × 7 × 1.2 mm2 | ND | 3.0 ± 1.1 mN 5.7 mN/cell |

11.8 ± 4.5 mN/mm2 | ND | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| hiPSC-CM | 1 × 106 | 100 -200 μm | ND | ND | ND | 55-80 bpm | Mathur et al., 2015 |

CM, cardiomyocytes; ESC, embryonic stem cell; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; ND, not determined; V, ventricular-type.

Passive stretch conditions have also improved the function of iPSC-derived and ESC-derived engineered heart tissue developed as collagen-based hydrogels [73]. Upons uniaxial cyclic stress is reminiscent of the cyclic, pulsatile stretch of the beating heart, cardiomyocyte size and proliferation increased, and force generation was length dependent [73].

2.3 Mechanical and electrical conditioning of engineered heart tissue

Maturation of the tissue can be advanced with mechanical and electrical conditioning (Table 2). In the heart, contractile forces Fcontraction are enhanced by stretch (i.e., the stretch of the ventricle upon filling) [86] [72, 73] . Electromechanical coupling is evident in collagen-based engineered tissues, which beat spontaneously and synchronously when exposed to static stress [61] [73]. This force generation is evident in constructs formed from either rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes or pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (PSC-CMs which include both ESC-CMs and iPSC-CMs. For example, in one report, engineered heart tissue produced a passive stress of 0.36 ± 0.06 mN and a total force of 0.75 ± 0.11mN [80]. In comparison, left ventricular heart muscle strips derived from the adult human heart have been reported to exert 21.7 ± 2.6 mN/mm2 of stress at maximum length [87]. Other examples of force generation profiles in engineered heart tissue are detailed in Table 2. Overall, mechanically conditioned engineered heart tissues can produce approximately up to 2-5% of the force compared to native tissue.

Electrical stimulation also conditions engineered heart tissue. Exogenous electric fields have been implicated in cardiac differentiation [88]. For example, electrical stimulation of collagen-based engineered heart tissue has resulted in ultrastructural organization and increased contractile force [85]. In another report, biphasic electrical stimulation of microtissue improved organization, elongation, and the presence of gap junction protein Connexin-43 [89]. Electrical field stimulation of biowires improved ultrastructural organization, conduction velocity, calcium handling, and electrophysiological properties [90]. Recently, optogenetics has been developed as a tool to induce action potentials using light stimulation [91]. Control of light-gated sodium channel with channelrhodopsin-2 induces a transmembrane potential leading to the propagation of an action potential [92]. This optogenetic tool initiates the process of excitation-contraction coupling, thereby acting as an “on-switch” for contraction [93]. Halorhodopsin is a light-gated pump for chloride ions that acts to repolarize and return ions to resting membrane potential [94]. Therefore, these genetic tools potentially can be used to mature cardiomyocyte contractile function through mechanical conditioning with light-controlled contraction.

2.4 Electrical function of engineered heart tissue

The quality of iPSC-derived heart tissue models is determined by its structure and function as compared to native human adult heart tissue. Quantitative measures of the functional maturity of engineered heart tissue include action potential properties, such as resting membrane potential, minimum excitation threshold, and conduction velocity. The overall electrophysiology of engineered heart tissue is less mature than native human heart tissue.

The resting membrane potential is an inherent property of the cell [95]. The mean ventricular and atrial resting membrane potentials of native human heart have been respectively reported at −87 mV and −70 mV; action potentials exist with both a prominent spike and a plateau [96]. For engineered heart tissue, action potential recordings are recorded on a representative cell population at the time of seeding [50] or on isolated cardiomyocytes after tissue formation [90, 97]. The resting membrane potential of CMs from engineered heart tissue (Ek = −96 mV) is hyperpolarized compared to that of the monolayer CM (approximately −60 mV) [98]. Based on initial work done with rats, action potential recordings from engineered rat heart tissue displayed stable resting membrane potentials of −66 to −78 mV, fast upstroke kinetics, and a prominent plateau phase [80]. Sharp electrode electrophysiology would be necessary to record resting membrane potentials from intact engineered heart tissue.

Engineered heart tissue has been reported to generate both spontaneous and elicited action potentials, and the minimum voltage (via electrical field stimulation) to elicit synchronous beating is referred to as the minimum excitation threshold (MET) [99]. MET is higher in engineered heart tissue (2.97 ± 0.30 V) compared to adult ventricular heart tissue (1.34 ± 0.17 V) [99]. MET can be reduced closer to physiological levels after electrical conditioning and consequent improvement of excitation-coupling [89]. However, others have demonstrated that the MET remained unaffected by electrical pacing [100]. Cellular composition affects the MET, such that constructs with 100% CMs had a MET of 3.2 V/cm whereas constructs with 60% CM purity had 5 V/cm [101]. Furthermore, MET is also affected by tissue orientation and tissue heterogeneity, which may introduce secondary excitation sources and incorrect low excitation thresholds [102, 103]. Thus, heterogeneities in the engineered heart tissue as well as electrode and bath geometry are important considerations when interpreting the electrical function of engineered heart tissue.

In conjunction with MET, the extent of gap junction coupling affects the kinetics of repolarizing and depolarizing currents and is reflected in the maximum capture rate (MCR), or the maximum rate at which engineered cardiac tissues can be steadily stimulated by a point electrode [104]. In response to electrical field stimulation, the MCR is approximately 180 to 270 beats/min [101]. In comparison, the MCR for neonatal and adult ventricular tissue is greater at 475.0 ± 25.0 and 281.2 ± 21.0 beats/min, respectively [99]. Native tissue has a higher MCR and a lower MET compared to engineered tissue.

The conduction velocity of the propagating action potential is a metric of cardiomyocyte gap junction coupling as well as the initiation of the action potential, which is dependent on both the sodium conductance and the resting membrane potential [104]. The conduction velocity is approximately one-third lower in engineered heart tissue compared to native adult human ventricular tissue: native adult human ventricular tissue has a conduction velocity of 45 cm/s [105], or in a more recent report, 31.69 ± 4.44 cm/s [99], whereas the recorded conduction velocity of engineered heart tissue is 11.89 ± 0.46 cm/s [50, 99]. However, the conduction velocity is dependent on CM composition and can be increased to approximately 25 cm/s at 90% hESC-CM purity [50]. Interestingly, conduction velocities are greater in 3D engineered heart tissues compared to age- and purity-matched 2D monolayers composed of 48-65% CM (9.76 ± 1.0 cm/s vs 5.17 ± 0.7 cm/s) [50]. In addition to cardiomyocyte purity, conduction velocities increase upon electrical stimulation [90].

Overall, the electrophysiological function of 3D-engineered heart tissue resembles physiological properties more closely than 2D counterpart models, as evident by various electrophysiological parameters such as resting membrane potential, minimum excitation threshold, and conduction velocity.

3. Preparing engineered heart tissue for transplantation

3.1 Prevascularization of engineered heart tissues: on route for scale-up

During the development of heart tissue, the coronary circulation provides important factors through perfusion and paracrine signaling. There is strong motivation to pre-vascularize the in vitro generated tissues in order to achieve macrostructures of engineered tissue constructs with longer in vivo graft survival [106]. One approach has been to incorporate endothelial cells. Tulloch et al. have reported the formation of lumen-containing structures when adding human endothelial cells to human ESC-CMs and fibroblasts [73]. Determining the appropriate mixture of cells will be critical in developing engineered heart tissues that most closely mimic native heart tissue. There are no reports to date of vascular function or increased function of the cardiac tissue construct due to pre-vascularization with endothelial cells. However, there has been progress with the development of a vascular patch, consisting of human ESC-derived endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in fibrin, which has been shown to significantly improve LV function in a porcine model of post myocardial infarction [107].

3.2 Translational studies for integration and function

Animal models of transplanted engineered heart tissue have provided valuable insight regarding graft integration and in vivo function. Initial studies focused on implanted engineered heart tissue developed from neonatal rat cells (8 × 10 × 1 mm) around the circumference of hearts from syngeneic and immunosuppressed rats [74, 79]. Functionally, implanted EHMs did not improve left ventricular function; however, they were heavily vascularized after 14 days [74, 79]. When engineered heart tissue containing human cells (cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and stromal cells) were transplanted into athymic rats, the graft survived and formed human microvessels perfused by the host coronary circulation. Certainly, vascularization will be crucial for long-term survival and integration of the graft into the host [108].

Engineered heart tissue has also been implanted into injured heart models. Engineered heart tissue developed from neonatal heart cells (thickness/diameter, 1-4 mm/15 mm) was transplanted into immunosuppressed infarcted rat hearts [84]. The engineered heart tissue survived after implantation and supported contractile function of infarcted hearts, including electrical coupling to the native myocardium as well as physiological improvements such as the prevention of further dilation, induced systolic wall thickening of the infarcted myocardial segments, and improved fractional area shortening [84].

A porcine model of acute myocardial infarction has also been reported with the transplantation of iPSC-derived cardiac, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells that were embedded in a fibrin patch and insulin growth factor (IGF)-encapsulated microspheres [109]. Results showed integration of the engineered heart tissue into the host myocardium, generation of organized sarcomeric structures, and improved physiology (i.e., left ventricular function, myocardial metabolism, and ventricular wall stress, amongst others). This porcine study highlights the potential of utilizing human iPSC-derived cells for cardiac repair. It has also been shown that human ESC-CMs can be transplanted and can survive in non-human primate models of myocardial ischemia followed by reperfusion [110]. Animals with grafts demonstrated perfusion of the graft by the host vasculature, regular calcium transients, electromechanical synchronization to the host myocardium, and remuscularization of the infarcted heart [110]. This study demonstrated important phenomena of survival and integration of the cells into the host, raising the possibility that engineered heart tissue derived from these cells could further improve cell retention and functional improvement of the infarcted heart. Noninvasive imaging techniques that can follow the survival of these engrafted cells would be helpful in optimizing these preclinical studies [111, 112].

Results of iPSC-CMs have led to the initiation of the first human clinical trial using ESC-derived cardiac progenitors in a fibrin gel for patients with ischemic heart failure (ESCORT, NCT02057900). ESC-derived cardiac progenitors are sorted for CD15+/Isl1+ [113] and delivered at the epicardium. The trial is currently recruiting participants [114] and is designed to provide critical insight into the safety of engineered heart tissue in patients with heart ischemia.

4. Microstructures of engineered heart tissue

4.1 Microstructures to improve oxygen and nutrient diffusion rate limitations

The size of engineered heart tissue will be an important consideration for future clinical needs as a graft for the human heart. However, the size of engineered cardiac tissue is limited by the rate at which diffusion can deliver oxygen and nutrients to its core because cardiomyocytes cannot tolerate hypoxia for prolonged periods of time. Diffusion rates are sufficient up to a thickness of 100-128 μm [115, 116]. One solution is to rely upon vascularization of the graft by the host after implantation. However, this approach requires time and is suboptimal for the survival of the graft. Another approach is to decrease the size of the graft to dimensions that enable nutrient exchange solely by diffusion. The optimization of oxygen and nutrient transfer will improve long-term graft survival and host integration.

Microtissues engineered into microfluidic platforms can provide continuous nutrient exchange. The controlled organization of cells and their microenvironments have led to the development of engineered vascular perfusion systems (Table 1). Microphysiological systems (MPS) have been reported as 2D models for cardiac tissue that allow for gas and nutrient exchange via microfluidic channels surrounding the microtissue [3]. In MPS, cardiomyocytes are aligned, thus providing physiologically relevant microtissue structures. Because the continuous flow in the microfluidic chambers allows for drug testing, MPS is an exemplary model for predicting drug-induced toxicity [3].

Perfused bioreactor systems can also enhance mass transport between culture medium and cells of engineered cardiac constructs. Different vessels, including rotating vessels and mixed flasks for laminar and turbulent flows [117] as well as perfusion reactors [118], have been utilized successfully. Cardiac cell-gel constructs that were generated from neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes and collagen and that were cultured in perfusion reactors maintained a constant frequency of contractions upon electrical stimulation, whereas constructs in rotating vessels exhibited episodes of arrhythmia [118]. It is not surprising that fluid mechanics plays a critical role in the development and function of heart tissue. After all, the heart is a highly dynamic organ with complex flow profiles. Given that bioreactor systems are nascent technologies for cardiac tissue engineering, continued research will be critical in understanding the effects of fluid flow on tissue, cellular, and molecular levels for incorporation into engineered heart tissue models.

4.2 Microtissues for force generation

Microtissues capture the phenomena of interactions between cells and the environment, and therefore are used to assess important cardiac properties in vitro. Methods to measure functional output (i.e., contractile force and action potential generation) are integrated into these systems. Heart-on-chip technology is a prime example of functional microtissues [119]. In this high throughput system, each sample consists of a thin sheet of cardiomyocytes. As the sheet contracts during contraction, deflections in tissue position are measured using image detection techniques, and subsequently, the amount of force generated can be calculated. Within the same system, action potential propagation can be measured. Heart-on-chip technology, thereby allowing high throughput analysis of mechanical and electrical output of a 2D cardiac tissue model. Similar studies have been done with microtissues generated from rat neonatal ventricular myocytes and collagen and around flexible posts; forces were calculated from beam bending theory based on the stiffness of the posts and ranged from 6-15 μN [100]. Overall, microtissues provide valuable models for studying a three-dimensional phenomenon of force generation without the limitation of diffusion-limited mass transfer.

5. iPSC-derived 3D models for disease modeling and drug screening

The use of iPSC-derived cells for tissue engineering is a nascent field. There is great promise in these tissues because they reflect the 3D interactions between cells and the environment within a personal genotype. Most recently, microtissues have been developed to model DCM [120]. Findings using the 3D model indicate that certain titin mutations are pathogenic and cause DCM by disrupting critical linkages in the sarcomere, diminishing contractile properties, and impairing response to mechanical and β-adrenergic stress [120]. In another example, a mirostructured 3D model of iPSC-CMs has been used to model Barth syndrome, a mitochondrial myopathy of the myocardium and skeletal muscle caused by a mutation in the gene Tafazzin (TAZ) [121]. iPSC-CMs carrying the TAZ mutation were studied using heart-on-chip technology and were noted to have structural sarcomeric abnormalities and weakened contraction; they also displayed lower contractile stresses, recapitulating the Barth phenotype in patients. Phenotypic rescue was achieved using small molecule treatments [121].

Engineered heart tissue is also being developed for drug screening, in particular microphysiological systems (MPS) using human iPSC-CMs. Pharmacological agents have been tested in these MPS, including isoproterenol (β-adrenergic agonist), E-4031 (hERG blocker), as well as two drugs with known clinical effects, verapamil (multi-ion channel blocker) and metoprolol (β-adrenergic antagonist) [122]; beat rate and mechanical motion were used as metrics of cardiac tissue function.

6. Limitations of current engineered heart tissues

The predictive abilities of engineered tissue systems are still limited, as these constructs do not recapitulate the human in vivo structure and organization of the myocardium. The structure of engineered heart tissue more closely resembles the organization of neonatal heart tissue. Native heart beat rates can be achieved, but maximum force produced per cross-sectional area of tissue is only 1% of native tissue. The stiffness, as indicated by the Young's modulus, of engineered heart tissue is half of native tissue, which is about 200 kPa [123]. Although microtissues circumvent the issues of diffusion-limited mass transfer, size of engineered tissue will become important in the field of precision medicine. Accordingly, it will also be important to understand whether the tissue construct will couple to the native heart. Encouragingly, in rat studies, electrical pacing of an implanted engineered heart tissue resulted in remote electrical propagation in the myocardium, suggesting coupling of the engineered heart tissue graft to the host myocardium [84]. As the field of tissue engineering continues to grow, established metrics will facilitate the comparison between designs. The ability to compare the quality of iPSC-CMs across laboratories will be possible with an established set of standards [45]. For example, in order to compare force measurements across models and laboratories, a common method for reporting force (i.e., stress/cell) will need to be adopted. This model will need to capture information about the force distribution throughout the tissue as well as the load experienced by each cell. These standards should address genetic, structural, electrophysiological, and contractile parameters as compared to a native ventricular cardiomyocyte [124].

7. Conclusions

There has been great progress in developing a heart tissue model that can provide force output – the ultimate functional readout of the myocardium. Microsystems provide mechanical and/or electrical conditioning in a micro-sized environment that enables maturation of the engineered tissue while incorporating cell and environmental interactions and functional readouts of force and/or electrophysiology. Scaling the tissue construct has been possible with technological advances in iPSC generation and iPSC-CM differentiation. Diffusion-limited nutrient delivery is addressed technologically with incorporated systems of controlled rate mass exchange or biologically with the inclusion of cells for tissue pre-vascularization.

The future direction of engineered heart tissue technology will be with combined research efforts in the areas of patient-derived cells and engineered tissues. This platform could be used to assess novel drug effects and screen for deleterious effects such as arrhythmias, impaired contractile force, and cardiotoxicity; therefore, it could serve as a valuable tool for new drugs before clinical trials.

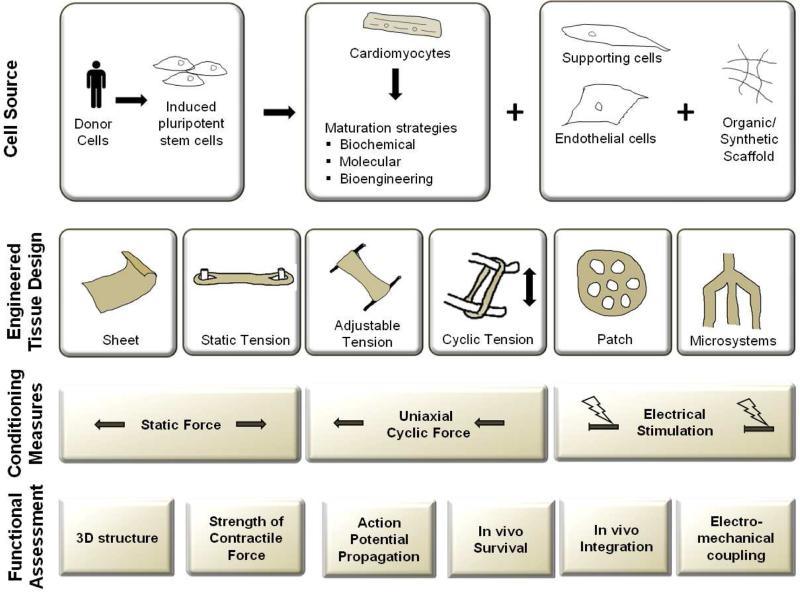

Fig 3. Current protocols in engineered heart tissue.

The most current engineered heart tissues include cardiomyocytes and an organic/synthetic scaffold, and sometimes also endothelial cells and supporting cells. The advent of iPSC-CMs makes it possible to fabricate patient-specific engineered heart tissues. There are various forms of conditioning, including mechanical stress (static and cyclic) and electrical stimulation. Measurable outputs include structural, mechanical, and electrical information as well as in vivo graft performance (survival, integration, and electromechanical coupling with the host).

Acknowledgements

We thank Blake Wu and Joseph Gold for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank funding support from the National Institute of Health (NIH) 1T32HL098049 (ET), NIH U01 HL099776, California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) TR3-05556, DR2-05394, and RT3-07798 (JCW). Because of space limitation, we are unable to include all of the important relevant papers; we apologize in advance to the investigators whose significant contributions to this field we have omitted here.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laslett LJ, Alagona P, Jr., Clark BA, 3rd, Drozda JP, Jr., Saldivar F, Wilson SR, Poe C, Hart M. The worldwide environment of cardiovascular disease: prevalence, diagnosis, therapy, and policy issues: a report from the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:S1–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herper M. The cost of creating a new drug now $5 billion, pushing big pharma to change. Forbes.com. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathur A, Loskill P, Hong S, Lee J, Marcus SG, Dumont L, Conklin BR, Willenbring H, Lee LP, Healy KE. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-based microphysiological tissue models of myocardium and liver for drug development. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(Suppl 1):S14. doi: 10.1186/scrt375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desmond-Hellmann S. The Cost of Creating A New Drug Now $5 Billiion. Pushing Big Pharma To Change, Forbes. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engle SJ, Puppala D. Integrating human pluripotent stem cells into drug development. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munos BH, Chin WW. A call for sharing: adapting pharmaceutical research to new realities. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferri N, Siegl P, Corsini A, Herrmann J, Lerman A, Benghozi R. Drug attrition during pre-clinical and clinical development: understanding and managing drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138:470–484. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchinson L, Kirk R. High drug attrition rates--where are we going wrong? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:189–190. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mordwinkin NM, Burridge PW, Wu JC. A review of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for high-throughput drug discovery, cardiotoxicity screening, and publication standards. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9423-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandenius CF, Steel D, Noor F, Meyer T, Heinzle E, Asp J, Arain S, Kraushaar U, Bremer S, Class R, Sartipy P. Cardiotoxicity testing using pluripotent stem cell-derived human cardiomyocytes and state-of-the-art bioanalytics: a review. J Appl Toxicol. 2011;31:191–205. doi: 10.1002/jat.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beqqali A, van Eldik W, Mummery C, Passier R. Human stem cells as a model for cardiac differentiation and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:800–813. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8476-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandenburger M, Wenzel J, Bogdan R, Richardt D, Nguemo F, Reppel M, Hescheler J, Terlau H, Dendorfer A. Organotypic slice culture from human adult ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:50–59. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsa E, Burridge PW, Wu JC. Human stem cells for modeling heart disease and for drug discovery. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:239ps236. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaese S, Verheule S. Cardiac electrophysiology in mice: a matter of size. Front Physiol. 2012;3:345. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence CL, Pollard CE, Hammond TG, Valentin JP. In vitro models of proarrhythmia. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1516–1522. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang P, Lan F, Lee AS, Gong T, Sanchez-Freire V, Wang Y, Diecke S, Sallam K, Knowles JW, Wang PJ, Nguyen PK, Bers DM, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Drug screening using a library of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes reveals disease-specific patterns of cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2013;127:1677–1691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, Lin ZC, Churko JM, Ebert AD, Lan F, Diecke S, Huber B, Mordwinkin NM, Plews JR, Abilez OJ, Cui B, Gold JD, Wu JC. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2014;11:855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lian X, Hsiao C, Wilson G, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Azarin SM, Raval KK, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1848–1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'Souza SL, Ang YS, Schaniel C, Lee DF, Yang L, Kaplan AD, Adler ED, Rozov R, Ge Y, Cohen N, Edelmann LJ, Chang B, Waghray A, Su J, Pardo S, Lichtenbelt KD, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD, Lemischka IR. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, Jung CB, Lam JT, Bott-Flugel L, Dorn T, Goedel A, Hohnke C, Hofmann F, Seyfarth M, Sinnecker D, Schomig A, Laugwitz KL. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Caspi O, Winterstern A, Feldman O, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Hammerman H, Boulos M, Gepstein L. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, Han L, Sanchez-Freire V, Abilez OJ, Navarrete EG, Hu S, Wang L, Lee A, Pavlovic A, Lin S, Chen R, Hajjar RJ, Snyder MP, Dolmetsch RE, Butte MJ, Ashley EA, Longaker MT, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:130–147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, Sanchez-Freire V, Nguyen PK, Wang L, Han L, Yen M, Wang Y, Sun N, Abilez OJ, Hu S, Ebert AD, Navarrete EG, Simmons CS, Wheeler M, Pruitt B, Lewis R, Yamaguchi Y, Ashley EA, Bers DM, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, Pasca AM, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer J, Dolmetsch RE. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011;471:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nature09855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebert AD, Kodo K, Liang P, Wu H, Huber BC, Riegler J, Churko J, Lee J, de Almeida P, Lan F, Diecke S, Burridge PW, Gold JD, Mochly-Rosen D, Wu JC. Characterization of the molecular mechanisms underlying increased ischemic damage in the aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 genetic polymorphism using a human induced pluripotent stem cell model system. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:255ra130. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morita H, Wu J, Zipes DP. The QT syndromes: long and short. Lancet. 2008;372:750–763. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sallam K, Li Y, Sager PT, Houser SR, Wu JC. Finding the rhythm of sudden cardiac death: new opportunities using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2015;116:1989–2004. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincen GM, Green ED, Keating MT. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, Han L, Sanchez-Freire V, Abilez OJ, Navarrete EG, Hu S, Wang L, Lee A, Pavlovic A, Lin S, Chen R, Hajjar RJ, Snyder MP, Dolmetsch RE, Butte MJ, Ashley EA, Longaker MT, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:130ra147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson B, Hamm C, Persson S, Wikstrom G, Sinagra G, Hjalmarson A, Waagstein F. Improved exercise hemodynamic status in dilated cardiomyopathy after beta-adrenergic blockade treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1397–1404. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelmeier RS, O'Connell JB, Walsh R, Rad N, Scanlon PJ, Gunnar RM. Improvement in symptoms and exercise tolerance by metoprolol in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation. 1985;72:536–546. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW, Antman EM, Smith SC, Jr., Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu H, Lee J, Vincent LG, Wang Q, Gu M, Lan F, Churko JM, Sallam KI, Matsa E, Sharma A, Gold JD, Engler AJ, Xiang YK, Bers DM, Wu JC. Epigenetic Regulation of Phosphodiesterases 2A and 3A Underlies Compromised beta-Adrenergic Signaling in an iPSC Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Cell Stem Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsa E, Rajamohan D, Dick E, Young L, Mellor I, Staniforth A, Denning C. Drug evaluation in cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells carrying a long QT syndrome type 2 mutation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:952–962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keung W, Boheler KR, Li RA. Developmental cues for the maturation of metabolic, electrophysiological and calcium handling properties of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5:10.1186. doi: 10.1186/scrt406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Heuvel NH, van Veen TA, Lim B, Jonsson MK. Lessons from the heart: Mirroring electrophysiological characteristics during cardiac development to in vitro differentiation of stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;67:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Pabon L, Murry CE. Engineering Adolescence Maturation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2014;114:511–523. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mummery CL, Zhang J, Ng ES, Elliott DA, Elefanty AG, Kamp TJ. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells to cardiomyocytes a methods overview. Circ Res. 2012;111:344–358. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsa E, Burridge PW, Wu JC. Human stem cells for modeling heart disease and for drug discovery. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:239ps236–239ps236. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo L, Abrams RM, Babiarz JE, Cohen JD, Kameoka S, Sanders MJ, Chiao E, Kolaja KL. Estimating the risk of drug-induced proarrhythmia using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2011;123:281–289. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mummery CL, Zhang J, Ng ES, Elliott DA, Elefanty AG, Kamp TJ. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells to cardiomyocytes: a methods overview. Circ Res. 2012;111:344–358. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang X, Pabon L, Murry CE. Engineering adolescence: maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2014;114:511–523. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hwang HS, Kryshtal DO, Feaster TK, Sanchez-Freire V, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Hong CC, Wu JC, Knollmann BC. Comparable calcium handling of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes generated by multiple laboratories. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novak A, Barad L, Zeevi-Levin N, Shick R, Shtrichman R, Lorber A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Binah O. Cardiomyocytes generated from CPVTD307H patients are arrhythmogenic in response to beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:468–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satin J, Kehat I, Caspi O, Huber I, Arbel G, Itzhaki I, Magyar J, Schroder EA, Perlman I, Gepstein L. Mechanism of spontaneous excitability in human embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:479–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burridge PW, Keller G, Gold JD, Wu JC. Production of de novo cardiomyocytes: human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma J, Guo L, Fiene SJ, Anson BD, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ, Kolaja KL, Swanson BJ, January CT. High purity human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: electrophysiological properties of action potentials and ionic currents. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2006–2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00694.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang D, Shadrin IY, Lam J, Xian HQ, Snodgrass HR, Bursac N. Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5813–5820. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, Sanchez-Freire V, Nguyen PK, Wang L, Han L, Yen M, Wang Y, Sun N. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang P, Lan F, Lee AS, Gong T, Sanchez-Freire V, Wang Y, Diecke S, Sallam K, Knowles JW, Wang PJ. Drug Screening Using a Library of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes Reveals Disease-Specific Patterns of Cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2013;127:1677–1691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma J, Guo L, Fiene SJ, Anson BD, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ, Kolaja KL, Swanson BJ, January CT. High purity human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: electrophysiological properties of action potentials and ionic currents. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2006–H2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00694.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang J, Wilson GF, Soerens AG, Koonce CH, Yu J, Palecek SP, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation research. 2009;104:e30–e41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Caspi O, Winterstern A, Feldman O, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Hammerman H. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lahti AL, Kujala VJ, Chapman H, Koivisto A-P, Pekkanen-Mattila M, Kerkelä E, Hyttinen J, Kontula K, Swan H, Conklin BR. Model for long QT syndrome type 2 using human iPS cells demonstrates arrhythmogenic characteristics in cell culture. Disease models & mechanisms. 2012;5:220–230. doi: 10.1242/dmm.008409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Narsinh KH, Sun N, Sanchez-Freire V, Lee AS, Almeida P, Hu S, Jan T, Wilson KD, Leong D, Rosenberg J. Single cell transcriptional profiling reveals heterogeneity of human induced pluripotent stem cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:1217. doi: 10.1172/JCI44635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lieu DK, Fu J-D, Chiamvimonvat N, Tung KWC, McNerney GP, Huser T, Keller G, Kong C-W, Li RA. Mechanism-based facilitated maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.973420. CIRCEP. 112.973420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu JD, Rushing SN, Lieu DK, Chan CW, Kong CW, Geng L, Wilson KD, Chiamvimonvat N, Boheler KR, Wu JC, Keller G, Hajjar RJ, Li RA. Distinct roles of microRNA-1 and -499 in ventricular specification and functional maturation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuppusamy KT, Jones DC, Sperber H, Madan A, Fischer KA, Rodriguez ML, Pabon L, Zhu WZ, Tulloch NL, Yang X, Sniadecki NJ, Laflamme MA, Ruzzo WL, Murry CE, Ruohola-Baker H. Let-7 family of microRNA is required for maturation and adult-like metabolism in stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E2785–2794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424042112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karakikes I, Ameen M, Termglinchan V, Wu JC. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes: Insights Into Molecular, Cellular, and Functional Phenotypes. Circ Res. 2015;117:80–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurokawa YK, George SC. Tissue engineering the cardiac microenvironment: Multicellular microphysiological systems for drug screening. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eschenhagen T, Fink C, Remmers U, Scholz H, Wattchow J, Weil J, Zimmermann W, Dohmen HH, Schafer H, Bishopric N, Wakatsuki T, Elson EL. Three-dimensional reconstitution of embryonic cardiomyocytes in a collagen matrix: a new heart muscle model system. FASEB J. 1997;11:683–694. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.8.9240969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McDonald TF, Sachs HG, DeHaan RL. Development of sensitivity to tetrodotoxin in beating chick embryo hearts, single cells, and aggregates. Science. 1972;176:1248–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4040.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vandenburgh HH, Karlisch P, Farr L. Maintenance of highly contractile tissue-cultured avian skeletal myotubes in collagen gel. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1988;24:166–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02623542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimmermann WH, Fink C, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, Eschenhagen T. Three-dimensional engineered heart tissue from neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;68:106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Angst BD, Khan LU, Severs NJ, Whitely K, Rothery S, Thompson RP, Magee AI, Gourdie RG. Dissociated spatial patterning of gap junctions and cell adhesion junctions during postnatal differentiation of ventricular myocardium. Circulation research. 1997;80:88–94. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vaidya D, Tamaddon HS, Lo CW, Taffet SM, Delmar M, Morley GE, Jalife J. Null mutation of connexin43 causes slow propagation of ventricular activation in the late stages of mouse embryonic development. Circulation research. 2001;88:1196–1202. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circulation research. 2001;88:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zimmerman RL, Das KM, Burke MA, Young NA, Solomides CC, Bibbo M. The clinical utility of the Das-1 monoclonal antibody in identifying adenocarcinoma of the colon metastatic to the liver in fine-needle aspiration tissue. Cancer. 2002;96:370–373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liau B, Christoforou N, Leong KW, Bursac N. Pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac tissue patch with advanced structure and function. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9180–9187. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Razumova MV, Korte FS, Regnier M, Hauch KD, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Murry CE. Growth of engineered human myocardium with mechanical loading and vascular coculture. Circ Res. 2011;109:47–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zimmermann WH, Didie M, Wasmeier GH, Nixdorff U, Hess A, Melnychenko I, Boy O, Neuhuber WL, Weyand M, Eschenhagen T. Cardiac grafting of engineered heart tissue in syngenic rats. Circulation. 2002;106:I151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Evans CL, Hill AV. The relation of length to tension development and heat production on contraction in muscle. J Physiol. 1914;49:10–16. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1914.sp001684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knowlton FP, Starling EH. The influence of variations in temperature and blood-pressure on the performance of the isolated mammalian heart. J Physiol. 1912;44:206–219. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1912.sp001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roy CS. On the Influences which Modify the Work of the Heart. J Physiol. 1879;1:452–496. 458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1879.sp000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Katz AM. Ernest Henry Starling, his predecessors, and the “Law of the Heart”. Circulation. 2002;106:2986–2992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000040594.96123.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eschenhagen T, Didie M, Munzel F, Schubert P, Schneiderbanger K, Zimmermann WH. 3D engineered heart tissue for replacement therapy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97(Suppl 1):I146–152. doi: 10.1007/s003950200043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zimmermann WH, Schneiderbanger K, Schubert P, Didie M, Munzel F, Heubach JF, Kostin S, Neuhuber WL, Eschenhagen T. Tissue engineering of a differentiated cardiac muscle construct. Circ Res. 2002;90:223–230. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fung Y.-c. A first course in continuum mechanics. Prentice-Hall, Inc.; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. p. 351. 1977. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zimmermann WH, Melnychenko I, Eschenhagen T. Engineered heart tissue for regeneration of diseased hearts. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1639–1647. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hibberd MG, Jewell BR. Calcium- and length-dependent force production in rat ventricular muscle. J Physiol. 1982;329:527–540. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zimmermann WH, Melnychenko I, Wasmeier G, Didie M, Naito H, Nixdorff U, Hess A, Budinsky L, Brune K, Michaelis B, Dhein S, Schwoerer A, Ehmke H, Eschenhagen T. Engineered heart tissue grafts improve systolic and diastolic function in infarcted rat hearts. Nat Med. 2006;12:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nm1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Radisic M, Park H, Shing H, Consi T, Schoen FJ, Langer R, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Functional assembly of engineered myocardium by electrical stimulation of cardiac myocytes cultured on scaffolds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:18129–18134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407817101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Solaro RJ. Mechanisms of the Frank-Starling law of the heart: the beat goes on. Biophys J. 2007;93:4095–4096. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holubarsch C, Ruf T, Goldstein DJ, Ashton RC, Nickl W, Pieske B, Pioch K, Ludemann J, Wiesner S, Hasenfuss G, Posival H, Just H, Burkhoff D. Existence of the Frank-Starling mechanism in the failing human heart. Investigations on the organ, tissue, and sarcomere levels. Circulation. 1996;94:683–689. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Serena E, Figallo E, Tandon N, Cannizzaro C, Gerecht S, Elvassore N, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Electrical stimulation of human embryonic stem cells: cardiac differentiation and the generation of reactive oxygen species. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:3611–3619. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chiu LL, Iyer RK, King JP, Radisic M. Biphasic electrical field stimulation aids in tissue engineering of multicell-type cardiac organoids. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1465–1477. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nunes SS, Miklas JW, Liu J, Aschar-Sobbi R, Xiao Y, Zhang B, Jiang J, Masse S, Gagliardi M, Hsieh A, Thavandiran N, Laflamme MA, Nanthakumar K, Gross GJ, Backx PH, Keller G, Radisic M. Biowire: a platform for maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2013;10:781–787. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Deisseroth K. Optogenetics. Nature methods. 2011;8:26–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abilez OJ, Wong J, Prakash R, Deisseroth K, Zarins CK, Kuhl E. Multiscale computational models for optogenetic control of cardiac function. Biophys J. 2011;101:1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abilez OJ. Cardiac optogenetics. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2012:1386–1389. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matsuno-Yagi A, Mukohata Y. Two possible roles of bacteriorhodopsin; a comparative study of strains of Halobacterium halobium differing in pigmentation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;78:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)91245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weiss TF. Cellular Biophysics, 2v.: Transport and Electrical Properties. MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trautwein W, Kassebaum DG, Nelson RM. Hechthh, Electrophysiological study of human heart muscle. Circ Res. 1962;10:306–312. doi: 10.1161/01.res.10.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schaaf S, Shibamiya A, Mewe M, Eder A, Stohr A, Hirt MN, Rau T, Zimmermann WH, Conradi L, Eschenhagen T, Hansen A. Human engineered heart tissue as a versatile tool in basic research and preclinical toxicology. PLoS One. 6:e26397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hoekstra M, Mummery CL, Wilde AA, Bezzina CR, Verkerk AO. Induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes as models for cardiac arrhythmias. Front Physiol. 2012;3:346. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bursac N, Papadaki M, Cohen RJ, Schoen FJ, Eisenberg SR, Carrier R, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Freed LE. Cardiac muscle tissue engineering: toward an in vitro model for electrophysiological studies. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H433–444. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Boudou T, Legant WR, Mu A, Borochin MA, Thavandiran N, Radisic M, Zandstra PW, Epstein JA, Margulies KB, Chen CS. A microfabricated platform to measure and manipulate the mechanics of engineered cardiac microtissues. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:910–919. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iyer RK, Chui J, Radisic M. Spatiotemporal tracking of cells in tissue-engineered cardiac organoids. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:196–207. doi: 10.1002/term.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gillis AM, Fast VG, Rohr S, Kleber AG. Mechanism of ventricular defibrillation. The role of tissue geometry in the changes in transmembrane potential in patterned myocyte cultures. Circulation. 2000;101:2438–2445. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Efimov IR, Nikolski VP, Salama G. Optical imaging of the heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:21–33. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130529.18016.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liau B, Zhang D, Bursac N. Functional cardiac tissue engineering. Regen Med. 2012;7:187–206. doi: 10.2217/rme.11.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Durrer D, van Dam RT, Freud GE, Janse MJ, Meijler FL, Arzbaecher RC. Total excitation of the isolated human heart. Circulation. 1970;41:899–912. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stevens KR, Kreutziger KL, Dupras SK, Korte FS, Regnier M, Muskheli V, Nourse MB, Bendixen K, Reinecke H, Murry CE. Physiological function and transplantation of scaffold-free and vascularized human cardiac muscle tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16568–16573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908381106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xiong Q, Hill KL, Li Q, Suntharalingam P, Mansoor A, Wang X, Jameel MN, Zhang P, Swingen C, Kaufman DS. A Fibrin Patch Based Enhanced Delivery of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Vascular Cell Transplantation in a Porcine Model of Postinfarction Left Ventricular Remodeling. Stem Cells. 2011;29:367–375. doi: 10.1002/stem.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Riegler J, Gillich A, Shen Q, Gold JD, Wu JC. Cardiac tissue slice transplantation as a model to assess tissue-engineered graft thickness, survival, and function. Circulation. 2014;130:S77–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ye L, Chang YH, Xiong Q, Zhang P, Zhang L, Somasundaram P, Lepley M, Swingen C, Su L, Wendel JS, Guo J, Jang A, Rosenbush D, Greder L, Dutton JR, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Kaufman DS, Ge Y. Cardiac repair in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiovascular cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chong JJ, Yang X, Don CW, Minami E, Liu YW, Weyers JJ, Mahoney WM, Van Biber B, Cook SM, Palpant NJ, Gantz JA, Fugate JA, Muskheli V, Gough GM, Vogel KW, Astley CA, Hotchkiss CE, Baldessari A, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Gill EA, Nelson V, Kiem HP, Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee AS, Xu D, Plews JR, Nguyen PK, Nag D, Lyons JK, Han L, Hu S, Lan F, Liu J, Huang M, Narsinh KH, Long CT, de Almeida PE, Levi B, Kooreman N, Bangs C, Pacharinsak C, Ikeno F, Yeung AC, Gambhir SS, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Preclinical derivation and imaging of autologously transplanted canine induced pluripotent stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32697–32704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nguyen PK, Riegler J, Wu JC. Stem cell imaging: from bench to bedside. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:431–444. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O'Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02057900, Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-derived Progenitors in Severe Heart Failure (ESCORT), (Last updated: March 31, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 115.Carrier RL, Papadaki M, Rupnick M, Schoen FJ, Bursac N, Langer R, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Cardiac tissue engineering: cell seeding, cultivation parameters, and tissue construct characterization. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;64:580–589. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990905)64:5<580::aid-bit8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Radisic M, Malda J, Epping E, Geng W, Langer R, Vunjak†Novakovic G. Oxygen gradients correlate with cell density and cell viability in engineered cardiac tissue. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2006;93:332–343. doi: 10.1002/bit.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Carrier RL, Rupnick M, Langer R, Schoen FJ, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Effects of oxygen on engineered cardiac muscle. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;78:617–625. doi: 10.1002/bit.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]