Abstract

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a colorectal cancer predisposition syndrome with considerable genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity, defined by the development of multiple adenomas throughout the colorectum. FAP is caused either by monoallelic mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene APC, or by biallelic germline mutations of MUTYH, this latter usually presenting with milder phenotype. The aim of the present study was to characterize the genotype and phenotype of Hungarian FAP patients. Mutation screening of 87 unrelated probands from FAP families (21 of them presented as the attenuated variant of the disease, showing <100 polyps) was performed using DNA sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Twenty-four different pathogenic mutations in APC were identified in 65 patients (75 %), including nine cases (37.5 %) with large genomic alterations. Twelve of the point mutations were novel. In addition, APC-negative samples were also tested for MUTYH mutations and we were able to identify biallelic pathogenic mutations in 23 % of these cases (5/22). Correlations between the localization of APC mutations and the clinical manifestations of the disease were observed, cases with a mutation in the codon 1200–1400 region showing earlier age of disease onset (p < 0.003). There were only a few, but definitive dissimilarities between APC- and MUTYH-associated FAP in our cohort: the age at onset of polyposis was significantly delayed for biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers as compared to patients with an APC mutation. Our data represent the first comprehensive study delineating the mutation spectra of both APC and MUTYH in Hungarian FAP families, and underscore the overlap between the clinical characteristics of APC- and MUTYH-associated phenotypes, necessitating a more appropriate clinical characterization of FAP families.

Keywords: Familial adenomatous polyposis, Colorectal cancer, Germline mutations, APC, MUTYH, Genotype–phenotype correlations

Introduction

Familial adenomatous polyposis is a rare colorectal cancer (CRC) predisposition syndrome, giving rise to approximately 1 % of all CRC cases and showing a distinctive phenotypic heterogeneity. In its autosomal dominant form (FAP1, OMIM#175100) it is characterized by the presence of hundreds or thousands of adenomas in the large bowel, and also by associated extracolonic manifestations including desmoid tumors, dental and skin abnormalities, retinal spots and malignant tumors of other organs. One of the colorectal polyps usually transforms into carcinoma at an early age [1–4]. A phenotypic variant of FAP1, called attenuated FAP (AFAP), shows less aggressive features, fewer (<100) adenomas, 10–15 years later age at disease onset [5–7] and require distinct surveillance and clinical management approaches [8–10].

FAP1 is caused by germline mutations of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, encoding a multifunctional gatekeeper tumor suppressor protein expressed in a wide variety of tissues. Constitutional pathogenic mutations are identifiable in 60–80 % of the classic FAP1 cases, but only in 10–30 % of AFAP patients [11–14].

In the past decade, a significant part of patients with (A)FAP without a detectable germline APC mutation have been found to carry biallelic mutations in the base excision repair gene MUTYH, a highly conserved DNA glycosylase involved in the repair of oxidative guanine damage. This discovery led to the description of FAP2 (OMIM#608456, usually known as MUTYH-associated polyposis, MAP), a recessively inherited phenotypic variant of familial adenomatous polyposis, with clinical features overlapping those of AFAP and classical FAP [14–19].

In the present study we examined the first set of (A)FAP patients from Hungary and one of the largest cohort from Central-Eastern Europe [20–25] in order to determine the mutational spectra of the APC and MUTYH genes diagnosed with colorectal polyposis to compare the clinical features of the mutation carriers and also to evaluate the respective roles of these genes in the inherited CRC burden in this Central-Eastern-European population.

Methods

Patients and samples

Individuals in this study were referred for genetic counselling and testing to the Department of Molecular Genetics at the National Institute of Oncology (Budapest, Hungary), through a 15-year service (1999–2014). All investigations have been carried out in agreement with internationally recognized guidelines, using study protocols approved by the Institutional Ethical Board. Written informed consent was provided by each patient. Included in this study were 87 patients from well-characterized familial adenomatous polyposis kindreds. The majority of cases presented the clinical symptoms of classical FAP, while 21 patients were diagnosed with <100 polyps and were classified as AFAP. Polyp counts are based on the endoscopic findings of gastroenterologists or on the reports of clinical pathologists. Since collecting family history information is still often neglected in the clinical practice, and self-reporting was also shown to be highly inaccurate [26, 27], reliable family history information gathered through past clinical records was available only for a minority of the patients/families involved. Therefore, this data was not used for the ab initio classification of the families.

Mutation analysis

DNA was extracted from blood samples of all consenting subjects using either the classic phenol–chloroform method or the ArchivePure DNA Blood Kit (5 Prime). The entire coding region and splice junctions of the APC gene were amplified by PCR (primer sequences are available upon request). Mutation screening was performed using direct bidirectional sequencing on an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies). The presence of all mutations was confirmed using a different blood sample. Additionally, the coding region of APC was screened for genomic copy number aberrations using the MLPA (multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification) Kit P043 (MRC-Holland), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and as described previously [28, 29].

All patients found negative for deleterious APC gene mutations were screened for the presence of variants in the MUTYH gene, again by PCR amplification and direct bidirectional sequencing of all coding exons and neighbouring splice sites. The biallelic nature of MUTYH variants (i.e. their trans status) was ascertained for cases carrying two different mutations by inspecting their presence/absence in first-degree relatives, whenever such samples were available. Copy number analysis of the gene was performed using the MLPA Kit P378 (MRC-Holland).

The novel or recurrent status of the point mutations was assessed by comparing our data with those available in variant databases: HGMD Professional 2013.3 (release date 27th Sept 2013, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/); the InSiGHT Colon Cancer Gene Variant Databases [30] (http://chromium.liacs.nl/LOVD2/colon_cancer/home.php, Accessed on May-2014) and the APC mutation database [31] at http://www.umd.be/APC/ (accessed on May-2014).

Characterization of large deletions

To determine the exact lengths of deletions having both breakpoints within the APC gene, a combination of XL-PCR and sequencing by primer walking was applied, where all deletions required individual approaches in selecting the appropriate PCR cycle settings and primer designs. An example is outlined in the legend of Fig. 1.

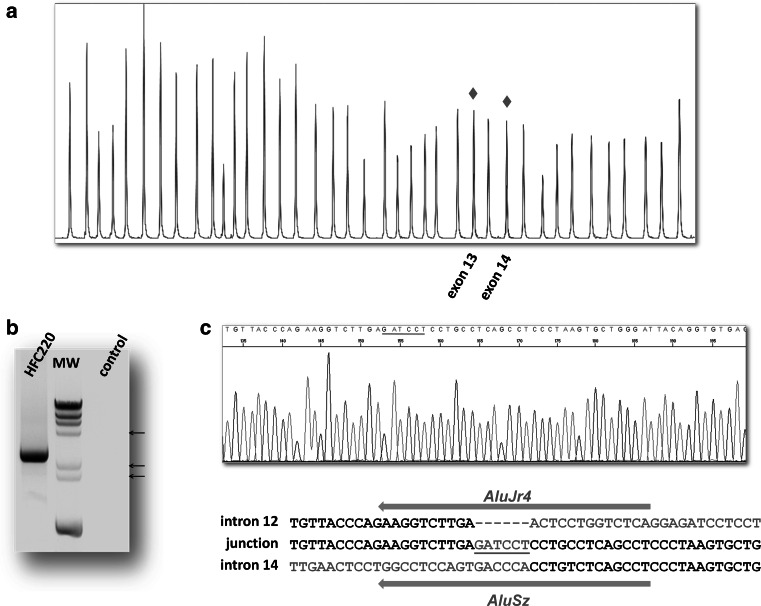

Fig. 1.

Identification and characterization of the large deletion (c.1627-185_1958+651del7146insGATCCT) in case HFC220. a MLPA analysis results of a heterozygous deletion removing exon 13 and 14 of the APC gene. The electropherogram of the patient (red) is superimposed on that of a control sample (blue). The peaks showing 50 % reduction of intensity are marked by red diamonds. The agarose gel image of the amplification product with primers located in intron 12 and intron 14 is shown on b. PCR was performed using the Multiplex PCR Kit (Qiagen) with short extension time (3.5 min), so the 9866 bp long normal fragment cannot be amplified (empty control lane). Case HFC220 shows a PCR product of approximately 3000 bp. The DRIgest III (GE Healthcare) molecular weight marker (MW) was used for this experiment, the 4.36, 2.32 and 2.03 kb fragments are indicated by arrows on the left side of the gel image. c The sequencing results of the above PCR product with a nested primer, showing the nucleotide sequence around the breakpoints. Red nucleotides are non-templated insertions, light grey letters are applied to mark deleted nucleotides. Grey arrows on top and below the sequences show the orientation of the Alu elements involved in the deletion. (Color figure online)

Although the precise localization of the deletion breakpoints that extended over the 5′ and/or 3′ gene boundaries has not been determined, gene dosage assays were performed to estimate the lengths of these sequence changes. Twenty-nine regions were used for copy number analyses from 7.6 MB upstream to 1.5 MB downstream of the APC gene, all selected from non-repetitive regions. Primer sequences and exact localization data are available upon request from the authors.

The first TaqMan-based gene dosage assays in our studies were performed as previously described [32]. At a later stage of our experiments, a different approach was preferred, and copy number determination was done using the robust dosage PCR (RD-PCR) methodology, in which the target locus and an internal control with known copy number are co-amplified [33, 34]. Briefly, PCR was performed in a duplex or triplex design containing primers for the target locus/loci and for an endogenous control with two copies. A touch-down setting was used in the amplification step: after initial denaturation and enzyme activation (95 °C for 15 min), 14 cycles were carried out with a denaturation step for 15 s at 95 °C, 20 s at the annealing temperature (starting from 62 °C and ending at 55 °C with 0.5 °C decrease per cycle), and extension for 30 s at 72 °C. This was followed by another 10 PCR cycles using 55 °C as annealing temperature (Multiplex PCR Kit, Qiagen). In order to decrease inter-individual variation, the DNA samples were heated (90 °C for 10 min) in 2 × TE (pH = 8.0) before adding the PCR mixture [35, 36]. The reaction products were run an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (High Sensitivity DNA Kit, Agilent), and copy number status of the target amplicon was assessed by comparing ratio-of-yield measures for input templates, using three-four negative control samples in each experiment (representative examples are shown on Fig. 2). For regions tested using both of the above methods, results were in concordance with each other.

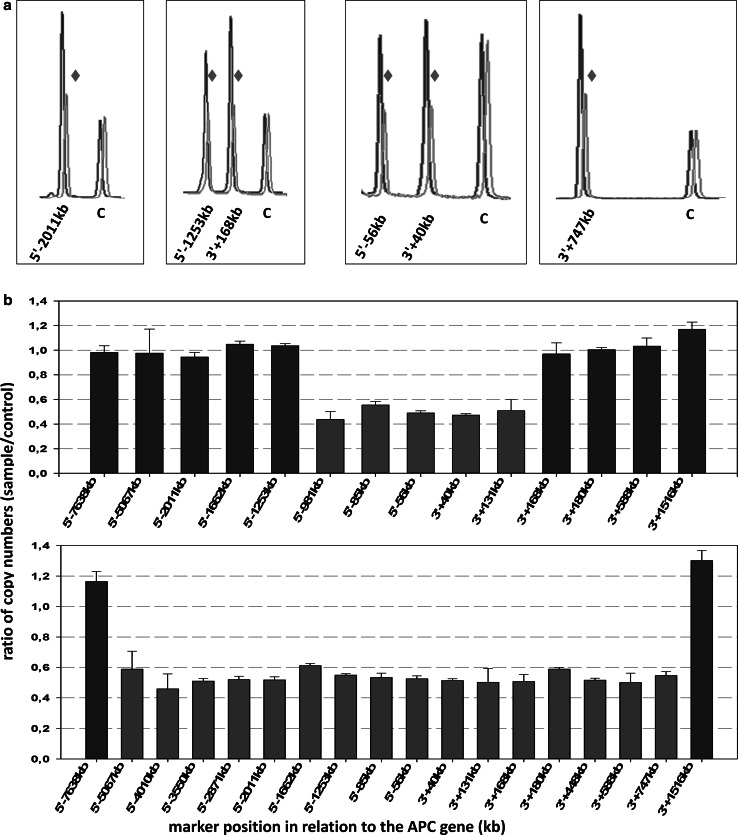

Fig. 2.

Approximate localization of large genomic deletions by robust dosage PCR (RD-PCR). a Examples of copy number determination at several regions in duplex and triplex RD-PCR assays. The electropherograms of the patient (case HFC208, red) were superimposed on those of a control sample (blue), and shifted slightly to the right for better visibility. The heights of the cntrol peaks (C) were adjusted to the same level. The deletion for a given amplicon (names given under each peak, reflecting the position of the given marker) is seen as a ~50 % reduction of peak intensity (red diamonds). b Diagram showing the approximate size of two deletions (case HFC106: upper; and HFC208: lower). The distance of the markers from the APC gene is given on the X axis (in kilobases, using negative numbers for upstream and positive numbers for downstream markers), while Y axis indicates the copy numbers normalized for the average of three control samples. A 40–60 % reduction for a given marker indicates the presence of the heterozygous deletion (red bars). Not all samples were tested for all positions. (Color figure online)

Mutation nomenclature

Naming of the variants complies with the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society [37, 38]: sequence changes are named in relation to the longest cDNA reference sequences (NM_000038.5 for APC and NM_001128425.1 for MUTYH), while predicted changes at the protein level are given according to the corresponding protein reference sequences (APC: NP_000029.2 and MUTYH: NP_001121897.1).

Statistics

Differences between groups were calculated by comparison of means using the Student’s t test, with p values less than 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 87 unrelated probands (52 males and 35 females) with familial adenomatous polyposis were included in this study. The median age of diagnoses was 27 years (ranging from 6 to 53 years). The majority of the patients (66/87, 76 %) showed symptoms of profuse, classical polyposis with several hundreds or thousands of polyps in the large bowel, the rest could be classified as attenuated FAP (AFAP) cases with less than 100 adenomatous polyps present. Clinical data on extracolonic manifestations were only rarely available, but five cases were reported to have a known phenotypic variant of FAP (four probands with Gardner syndrome and one with Turcot syndrome). Available clinical and mutation data are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Pathogenic APC variants: substitutions and small indels

| Family | Agea | Polypb | Pheno-typec | Coding exon | Mutation | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Predicted protein | ||||||

| HFC005 | 25 | ++ | AFAP | 3 | c.416_419del4 | p.Lys139Argfs*30 | [39] |

| HFC068 | 43 | ++ | AFAP | 3 | c.416_419del4 | p.Lys139Argfs*30 | [39] |

| HFC201 | 42 | +++ | cFAP,G | 4 | c.423-2A>G | Skipping of exon 4 | [40] |

| HFC127 | 34 | ++ | AFAP | 4 | c.423G>T | Skipping of exon 4 | [41] |

| HFC043 | 44 | +++ | cFAP | 4 | c.513_516del4 | p.Pro173* | Novel |

| HFC024 | 40 | +++ | cFAP | 5 | c.556delA | p.Arg186Glufs*19 | [42] |

| HFC122 | 23 | +++ | cFAP | 6 | c.646C>T | p.Arg216* | [43] |

| HFC079 | 33 | + | AFAP | 6 | c.694C>T | p.Arg232* | [44] |

| HFC137 | 24 | ++ | AFAP | 7 | c.793G>T | p.Gly265* | Novel |

| HFC044 | 24 | +++ | cFAP | 13 | c.1690C>T | p.Arg564* | [45] |

| HFC135 | 29 | +++ | cFAP | 13 | c.1690C>T | p.Arg564* | [45] |

| HFC224 | 35 | +++ | cFAP | 13 | c.1738A>T | p.Lys580* | [46] |

| HFC223 | 16 | +++ | cFAP | 14 | c.1748dupC | p.Thr584Asnfs*18 | Novel |

| HFC144 | 22 | +++ | cFAP | 14 | c.1886delT | p.Leu629* | [47] |

| HFC062 | 43 | ++ | AFAP | 14 | c.1957A>G | Skipping of exon 14 | [41] |

| HFC082 | 36 | +++ | cFAP | 14 | c.1957A>G | Skipping of exon 14 | [41] |

| HFC063 | 44 | +++ | cFAP | 14 | c.1958+3A>G | Skipping of exon 14 | [41] |

| HFC015 | 27 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2138C>G | p.Ser713* | [4] |

| HFC249 | 18 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2186dupT | p.Met730Hisfs*4 | Novel |

| HFC129 | 27 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2387_2388delAT | p.Tyr796Trpfs*2 | [48] |

| HFC194 | 26 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2413C>T | p.Arg805* | [49] |

| HFC095 | 34 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2545delG | p.Asp849Ilefs*12 | Novel |

| HFC070 | 25 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2626C>T | p.Arg876* | [50] |

| HFC217 | 21 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2626C>T | p.Arg876* | [50] |

| HFC170 | 29 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2805C>G | p.Tyr935* | [51] |

| HFC026 | 27 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2973_2976del4 | p.Lys993Phefs*11 | Novel |

| HFC240 | 30 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.2984delG | p.Cys995Serfs*10 | Novel |

| HFC020 | 27 | +++ | cFAP,T | 15 | c.3183_3187del5 | p.Gln1062* | [44] |

| HFC036 | 36 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3183_3187del5 | p.Gln1062* | [44] |

| HFC221 | 15 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3183_3187del5 | p.Gln1062* | [44] |

| HFC222 | 23 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3183_3187del5 | p.Gln1062* | [44] |

| HNF001 | 38 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3183_3187del5 | p.Gln1062* | [44] |

| HFC008 | 16 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3186_3187delAA | p.Ser1063* | [47] |

| HFC101 | 19 | NA | cFAP | 15 | c.3203_3206del4 | p.Ser1068* | Novel |

| HFC061 | 17 | ++ | AFAP | 15 | c.3257_3258delAC | p.His1086Profs*32 | Novel |

| HFC065 | 39 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3257_3258delAC | p.His1086Profs*32 | Novel |

| HFC099 | 18 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3427delT | p.Tyr1143Ilefs*22 | [52] |

| HFC067 | 10 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3471_3474del4 | p.Glu1157Aspfs*7 | [53] |

| HFC033 | 28 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3473_3474delGA | p.Arg1158Thrfs*5 | [54] |

| HFC212 | 30 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3682C>T | p.Gln1228* | [47] |

| HFC080 | 15 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3880C>T | p.Gln1294* | [55] |

| HFC042 | 19 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3925_3928del4 | p.Glu1309Argfs*11 | [56] |

| HFC030 | 32 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3927_3931del5 | p.Glu1309Aspfs*4 | [44] |

| HFC038 | 13 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3927_3931del5 | p.Glu1309Aspfs*4 | [44] |

| HFC040 | 17 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3927_3931del5 | p.Glu1309Aspfs*4 | [44] |

| HFC152 | 17 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3927_3931del5 | p.Glu1309Aspfs*4 | [44] |

| HFC155 | 24 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3927_3931del5 | p.Glu1309Aspfs*4 | [44] |

| HFC233 | 20 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.3939delT | p.Arg1314Glyfs*7 | Novel |

| HFC089 | 6 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.4057G>T | p.Glu1353* | [57] |

| HFC187 | 24 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.4067C>A | p.Ser1356* | UMD.bed |

| HFC041 | 15 | ++ | AFAP | 15 | c.4099C>T | p.Gln1367* | [58] |

| HFC088 | 11 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.4268_4271del4 | p.Leu1423Glnfs*49 | Novel |

| HD001 | 19 | +++ | cFAP,G | 15 | c.4348C>T | p.Arg1450* | [59] |

| HFC213 | 42 | +++ | cFAP | 15 | c.4348C>T | p.Arg1450* | [59] |

| HFC200 | 27 | +++ | cFAP,G | 15 | c.4426delG | p.Val1476Phefs*31 | Novel |

| HFC018 | 20 | +++ | cFAP,G | 15 | c.4549C>T | p.Gln1517* | [60] |

Novel mutations are shown in italics

* Predicted Protein column are part of the official HGVS nomenclature (denoting STOP codon)

aAge of onset

bNumber of polyps found at diagnosis (+: <30; ++: 30–100; +++: >100; NA: not available)

ccFAP: classical FAP; AFAP: attenuated FAP; G: Gardner syndrome; T: Turcot syndrome

dListed in the APC mutation database at [http://www.umd.be/APC/] without reference

Table 2.

Pathogenic APC variants: large deletions

| Family | Agea | Polypb | Exon | Mutation name | Repetitive elementsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFC132 | 42 | ++ | 4 | c.423-1108_532-2193del4086 | AluJb/AluSc8 |

| HFC220 | 18 | +++ | 13–14 | c.1627-185_1958+651del7146insGATCCT | AluJr4/AluSz |

| HFC126 | 24 | +++ | 14 | c.1744-2465_1958+976del3656insGTAA | Non-Alu/AluSx1 |

| HFC145 | 45 | +++ | 0–13 | c.1-?_1743+?del | Not determined |

| HFC184 | 22 | ++ | 0–13 | c.1-?_1743+?del | Not determined |

| HFC203 | 32 | ++ | 0–13 | c.1-?_1743+?del | Not determined |

| HFC110 | 13 | +++ | 14–15 | c.1744-?_8532+? | Not determined |

| HFC106 | 26 | +++ | 0–15 | c.1-?_8532+?del | Not determined |

| HFC208 | 33 | +++ | 0–15 | c.1-?_8532+?del | Not determined |

aAge of diagnosis

bNumber of polyps found at diagnosis (++: 30–100; +++: >100)

cRepetitive elements located at the 5′/3′ breakpoints according to the RepeatMasker software [http://www.repeatmasker.org/]

Table 3.

Biallelic MUTYH mutations

| Family | Agea | Polypb | Exon | Mutation name | Consequence (predicted) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFC238 | 50 | +++ | 5 | c.504+19_504+31del13 | p.Lys155_Glu168del | [61] |

| 9 | c.734G>A | p.Arg245His | [62] | |||

| HFC006 | 51 | ++ | 6 | c.453_458dup | p.Thr152_Met153insIleTrp | [17] |

| 9 | c.734G>A | p.Arg245His | [62] | |||

| HFC185 | 35 | +++ | 6 | c.453_458dup | p.Thr152_Met153insIleTrp | [17] |

| 10 | c.933+3A>C | p.Gly264Trpfs*7 | [63] | |||

| HFC239 | 30 | ++ | 7 | c.536A>G | p.Tyr179Cys | [15] |

| 9 | c.734G>A | p.Arg245His | [62] | |||

| HFC049 | 46 | +++ | 9 | c.734G>A | p.Arg245His | [62] |

| 9 | c.734G>A | p.Arg245His |

aAge of onset

bNumber of polyps found at diagnosis (++: 30–100; +++: >100)

Mutations of the APC gene

Mutation analysis using direct sequencing and MLPA revealed the presence of a deleterious sequence variant in the APC gene in 75 % of the probands (65/87), with 52 % (11/21) among the AFAP patients and 82 % (54/66) among classical FAP probands. The mutation spectrum consists of nine genomic deletions (14 %), and 56 point mutations. Three of the large deletions could be localized with both breakpoints within the APC gene and involving Alu repeat elements (Fig. 1), while the other six extended over the gene boundaries, half of them affecting neighbouring genes, two of them containing the entire APC sequence (Figs. 2, 3). Of the 56 point mutations, 32 were small indels, 19 were nonsense substitutions and 5 were variants predicted to lead to altered splicing. The point mutations represent 42 different pathogenic changes, 12 (29 %) of them novel, one seen in two reportedly unrelated families. The most frequently occurring mutations (c.3183_3187del5; p.Gln1062* and c.3927_3931del5; p.Glu1309Aspfs*4) were seen in five probands each. A summary of the mutations found in our patients is given in Tables 1 and 2.

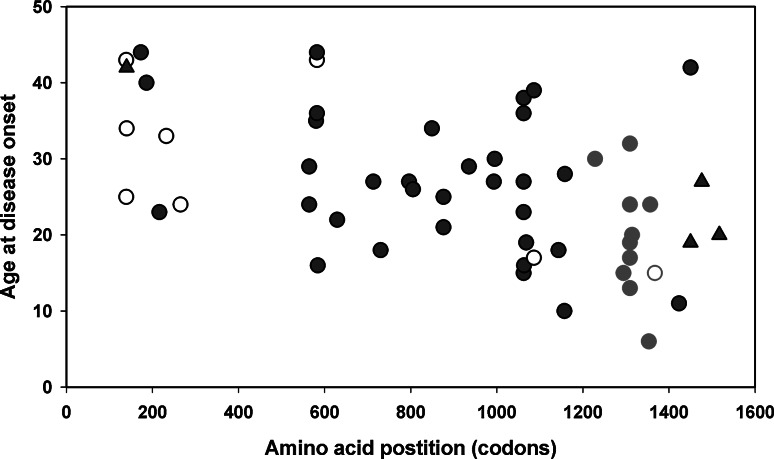

Fig. 3.

Genotype–phenotype correlations for substitution and small indels of the APC gene. The age of disease onset is shown in relation to the position of the mutated codon. For splice site mutations resulting in exon skipping, the last codon of the previous exon was used. To demonstrate genotype–phenotype correlations, mutations found in AFAP cases are depicted as empty symbols (clustering near the 5′ part of the gene), while the mutations of patients diagnosed with Gardner syndrome are shown as triangles (mostly after codon 1400). Red symbols are used to highlight the mutations within the codon 1200–1400 region, their carriers showing a significantly reduced age at disease onset as compared to the carriers of mutations located elsewhere in the gene. (Color figure online)

Biallelic MUTYH mutations

Twenty-two patients without evidence of pathogenic APC variants were analyzed for mutations in the MUTYH gene. Direct sequencing revealed five cases (23 %) with biallelic MUTYH mutations, three carriers with the classical FAP phenotype and two from the AFAP group. None of the mutations were novel (Table 3).

Genotype–phenotype correlations

Patients with constitutional APC mutations showed a median age of 26 years (range 6–45 years) at disease onset, which significantly differed (p = 0.018) from that of the mutation negative cases (median 37 years, ranging from 7 to 53 years), and those with biallelic MUTYH mutation (median 46 years ranging from 35 to 51 years p = 0,029). Biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers showed no difference compared to mutation negative cases (p = 0.084).

Extracolonic manisfestations were rarely reported, but three of the four Gardner syndrome cases described here (diagnosed with multiple adenomas together with desmoid tumors) were found to carry an inactivating APC mutation after codon 1400. The majority of AFAP cases were found to carry a pathogenic APC mutation located in the 5′ part of the gene (Table 1; Fig. 3). Regarding the association of the mutation position with the patients’ age at onset we demonstrated a significantly reduced age for those carrying a mutation in the 100 amino acid vicinity of codon 1300 as compared to those with mutations in other parts of the APC gene (p < 0.003) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

There is only limited information of the spectrum of APC and MUTYH mutations in the Central-Eastern-European region [20–25]. In this study the coding region of the APC gene has been screened for mutations in a panel of 87 unrelated probands diagnosed with familial adenomatous polyposis. The methods applied for mutation analysis included direct sequencing and also screening for copy number alterations using MLPA, and this combined approach allowed us to identify a pathogenic alteration in 75 % of the patients analysed, with 82 % of the classical FAP cases.

The scattered mutation pattern, the marked predominance of small deletions (more than half of the point mutations falling into that category) and also the relative frequency of large genomic alteration (14 %) is in agreement with most previous findings in European populations [64–67]. The frequency of the two most commonly identified mutations at codon hot spots 1062 and 1309 in our sample set was 12 % each, which falls into the same range as reported by several other groups [66, 68, 69].

From the total of 42 unique point mutations, 12 were novel (29 %), which is in concordance with the wide range of this type of alterations found in different populations (from 16 % in Koreans to >40 % in Northern Europe) [52, 70, 71] and also with the frequencies appearing in the Human Gene Mutation Database. This relatively high frequency of novel alterations underscores the need of screening different populations in order to reveal their possibly distinct mutational spectra.

Detection of large genomic alterations are recently included more often in the routine mutation screening protocols then before, but the detailed characterization of these changes requires more time and dedicated techniques, which usually are outside the capacity of most laboratories. Thus, large genomic deletions are rarely studied in detail [64, 67, 72], although at least some of them may extend into neighbouring regions which potentially have a modifier effect on the disease phenotype as exemplified by some recent studies including our group [29, 32, 73–75]. In our series of cases, nine large genomic deletions were identified, varying widely in size, ranging from single exon deletions to an extremely large deletion containing many genes.

Three of the large genomic alterations had both breakpoints located within the gene (deletion of exon 4, exon 14, and exons 13–14). For these cases we were able to determine the exact breakpoints, revealing a role of repetitive elements: different Alu sequences were involved in all cases, and in two instances a 4–6 bp non-template insertion at the breakpoint junction was also observed, indicating the classical non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) as the most likely mechanism responsible for these deletions [76–80].

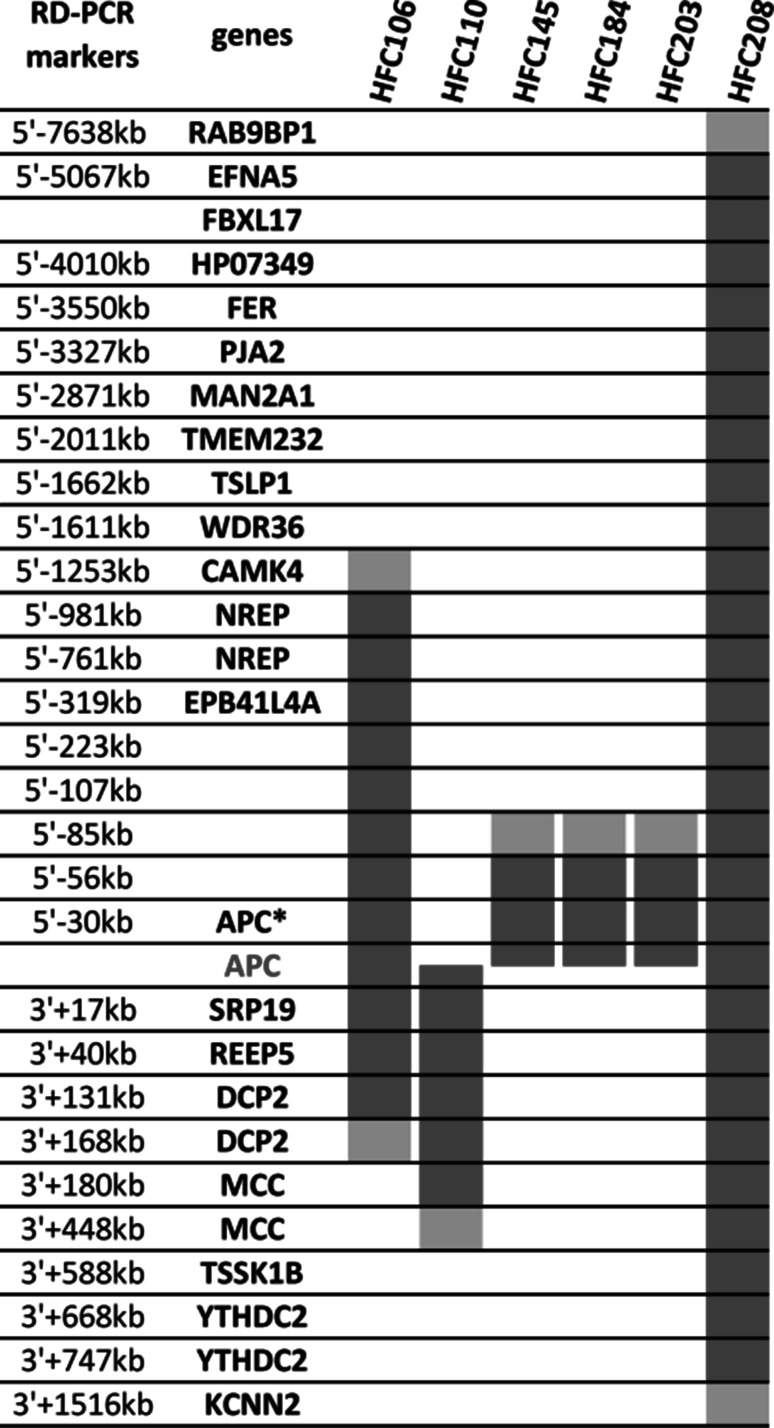

The remaining six deletions extended over the gene boundaries, half of them reaching other upstream and/or downstream genes. The exact breakpoints were not specified, but we applied two independent semiquantitative techniques to determine the copy numbers (gene dosage) in several regions outside the APC gene, thus mapping the approximate sizes of these mutations. One of them (sample HFC208) was found to be more than 4 MB long and also affected the coding regions of several genes up- and downstream of APC (Fig. 4). Although some of these genes were indicated in colorectal carcinogenesis [2, 81, 82], their heterozygous deletion did not seem to cause any modification in the polyposis and/or CRC phenotypes of the probands carrying them. However, given the small number of patients carrying such large genomic deletions in our study, a considerably larger dataset would be required to reliably assess the potential role of these neighbouring genes.

Fig. 4.

Germline large deletions extending over the boundaries of the APC gene. The localization of the known RefSeq genes of the chromosome 5 region 104,000,000–114,000,000 (coordinates are given according to the GRCh37/gh19 chromosome assembly) are shown schematically. The minimal and maximal sizes of the large genomic deletions are indicated for our six samples as red and pink bars, respectively. The loci where copy number analyses were done (RD-PCR markers) are shown on the left, their names reflecting their localization with respect to the coding portion of the APC gene. APC*: the 5′–30 kb RD-PCR marker is located in the first non-coding exon of APC. Markers without gene names are in intergenic regions. (Color figure online)

From the 22 FAP/AFAP patients found negative for germline APC mutations, biallelic MUTYH mutations accounted for five (23 %) cases, increasing the overall mutation detection rate to 80 %. Of the two mutations most frequently reported in the literature to date, p.Tyr179Cys and p.Gly396Asp, (responsible for ~80 % of pathogenic variants found in European populations [83]), only the former was found in one case, emphasizing the need to determine the possibly characteristic population-specific mutation patterns by a comprehensive screening of the whole coding sequence for the gene for all populations studied.

Understanding genotype–phenotype correlations is useful for the clinical management of (A)FAP families [8–10], but the relationships between the locations of the APC mutations and certain extracolonic manifestations are still not fully delineated, and as more patients are diagnosed with (A)FAP, a broader range of extracolonic manifestations has come to be recognized in this group. For our sample set the extracolonic manifestations were rarely reported, so the only statistically significant correlation we could demonstrate was the association between the age of disease onset and the location of the APC mutation in the codon 1200–1400 region, which is in agreement with several previous reports [46, 60, 84–87].

The inherent variability of the (A)FAP phenotype and also the overlap between APC- and MUTYH-linked phenotypes (that is, MUTYH mutations can be associated with classical FAP features) necessitate a more comprehensive approach for FAP screening to increase mutation detection yield. A combined analysis of the two genes with techniques allowing for the detection of both point mutations and large genomic alterations is needed for the exhaustive mutation testing of both classical FAP and attenuated FAP cases [13, 88, 89].

Finally, our patient series includes 17 families with no germline APC or MUTYH mutation detected, although ten of them belong to the classical FAP group with profuse polyposis. In these cases the age of disease onset was significantly older than that of the APC mutation carriers (34.5 vs. 26.7 years, p = 0.018), and almost 10 years younger than those with biallelic MUTYH mutations (44 years). Since APC/MUTYH-negative cases are noticeably enriched in AFAP patients, while the mutation positive group in classical FAP cases, we also compared age of onset data separately for the FAP and AFAP groups, and found no significant difference between mutation negative and positive cases (p = 0.18 for the AFAP and p = 0.3 for the FAP group). Mutation negative cases raise the possibility of yet uncovered genetic heterogeneity of FAP, the possible role of other predisposing genes [90, 91], but also the incompleteness of the routinely used mutation screening techniques: ignored, but potentially regulatory regions in introns or even outside the gene boundaries may also contribute to inactivation of a predisposing gene [73, 92–96].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants and their families for their cooperation. We thank Baloghné Kovács Mária, Frankó Judit, Ferencziné Rab Judit and Domokos Gabriella for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the Hungarian Research Grants KTIA-OTKA CK-80745, OTKA K-112228 (given to E.O.) and the Norwegian EEA Financial Mechanism, Hu0115/NA/2008-3/OP-9 (given to K.M., A.-L. B.-D. and E.O.).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H, Joslyn G, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Vogelstein B, Bryan TM, Levy DB, Smith KJ, Preisinger AC, Hamilton SR, Hedge P, Markham A, et al. Identification of a gene located at chromosome 5q21 that is mutated in colorectal cancers. Science. 1991;251:1366–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1848370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su LK, Vogelstein B, Bryan TM, Levy DB, Smith KJ, Preisinger AC, Hedge P, McKechnie D, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishisho I, Nakamura Y, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y, Ando H, Horii A, Koyama K, Utsunomiya J, Baba S, Hedge P. Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science. 1991;253:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1651563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spirio L, Olschwang S, Groden J, Robertson M, Samowitz W, Joslyn G, Gelbert L, Thliveris A, Carlson M, Otterud B, et al. Alleles of the APC gene: an attenuated form of familial polyposis. Cell. 1993;75:951–957. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearnhead NS, Britton MP, Bodmer WF. The ABC of APC. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:721–733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen AL, Bisgaard ML, Bülow S. Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP). A review of the literature. Fam Cancer. 2003;2:43–55. doi: 10.1023/A:1023286520725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasen HF, Möslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, Bernstein I, Bertario L, Blanco I, Bülow S, Burn J, Capella G, et al. Guidelines for the clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) Gut. 2008;57:704–713. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasen HF, Tomlinson I, Castells A. Clinical management of hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:88–97. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leoz ML, Carballal S, Moreira L, Ocaña T, Balaguer F. The genetic basis of familial adenomatous polyposis and its implications for clinical practice and risk management. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8:95–107. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S51484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieuwenhuis MH, Vasen HF. Correlations between mutation site in APC and phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): a review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;61:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claes K, Dahan K, Tejpar S, De Paepe A, Bonduelle M, Abramowicz M, Verellen C, Franchimont D, Van Cutsem E, Kartheuser A. The genetics of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and MutYH-associated polyposis (MAP) Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucci-Cordisco E, Risio M, Venesio T, Genuardi M. The growing complexity of the intestinal polyposis syndromes. Am J Med Genet. 2013;161A:2777–2787. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torrezan GT, da Silva FC, Santos EM, Krepischi AC, Achatz MI, Aguiar S, Jr, Rossi BM, Carraro DM. Mutational spectrum of the APC and MUTYH genes and genotype–phenotype correlations in Brazilian FAP, AFAP, and MAP patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Tassan N, Chmiel NH, Maynard J, Fleming N, Livingston AL, Williams GT, Hodges AK, Davies DR, David SS, Sampson JR, Cheadle JP. Inherited variants of MYH associated with somatic G:C→T: a mutations in colorectal tumors. Nat Genet. 2002;30:227–232. doi: 10.1038/ng828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson JR, Dolwani S, Jones S, Eccles D, Ellis A, Evans DG, Frayling I, Jordan S, Maher ER, Mak T, Maynard J, Pigatto F, Shaw J, Cheadle JP. Autosomal recessive colorectal adenomatous polyposis due to inherited mutations of MYH. Lancet. 2003;362:39–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieber OM, Lipton L, Crabtree M, Heinimann K, Fidalgo P, Phillips RK, Bisgaard ML, Orntoft TF, Aaltonen LA, Hodgson SV, Thomas HJ, Tomlinson IP. Multiple colorectal adenomas, classic adenomatous polyposis, and germ-line mutations in MYH. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:791–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen M, Joerink-van de Beld MC, Jones N, Vogt S, Tops CM, Vasen HF, Sampson JR, Aretz S, Hes FJ. Analysis of MUTYH genotypes and colorectal phenotypes in patients with MUTYH-associated polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:471–476. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Leon MP, Urso ED, Pucciarelli S, Agostini M, Nitti D, Roncucci L, Benatti P, Pedroni M, Kaleci S, Balsamo A, Laudi C, Di Gregorio C, Viel A, Rossi G, Venesio T. Clinical and molecular features of attenuated adenomatous polyposis in northern Italy. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohoutová M, Stekrová J, Jirásek V, Kapras J. APC germline mutations identified in Czech patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:460–461. doi: 10.1002/humu.9028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandrovcová J, Stekrová J, Kebrdlová V, Kohoutová M. Molecular analysis of the APC and MYH genes in Czech families affected by FAP or multiple adenomas: 13 novel mutations. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:397. doi: 10.1002/humu.9224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stekrova J, Sulova M, Kebrdlova V, Zidkova K, Kotlas J, Ilencikova D, Vesela K, Kohoutova M. Novel APC mutations in Czech and Slovak FAP families: clinical and genetic aspects. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sulová M, Zídková K, Kleibl Z, Stekrová J, Kebrdlová V, Bortlík M, Lukás M, Kohoutová M. Mutation analysis of the MYH gene in unrelated Czech APC mutation-negative polyposis patients. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1617–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plawski A, Slomski R. APC gene mutations causing familial adenomatous polyposis in Polish patients. J Appl Genet. 2008;49:407–414. doi: 10.1007/BF03195640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarzová L, Štekrová J, Florianová M, Novotný A, Schneiderová M, Lněnička P, Kebrdlová V, Kotlas J, Veselá K, Kohoutová M. Novel mutations of the APC gene and genetic consequences of splicing mutations in the Czech FAP families. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:35–42. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell RJ, Brewster D, Campbell H, Porteous ME, Wyllie AH, Bird CC, Dunlop MG. Accuracy of reporting of family history of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2004;53:291–295. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.027896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foo W, Young JM, Solomon MJ, Wright CM. Family history? The forgotten question in high-risk colorectal cancer patients. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:450–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papp J, Kovacs ME, Olah E. Germline MLH1 and MSH2 mutational spectrum including frequent large genomic aberrations in Hungarian hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer families: implications for genetic testing. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2727–2732. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i19.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plazzer JP, Sijmons RH, Woods MO, Peltomäki P, Thompson B, Den Dunnen JT, Macrae F. The InSiGHT database: utilizing 100 years of insights into Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grandval P, Blayau M, Buisine MP, Coulet F, Maugard C, Pinson S, Remenieras A, Tinat J, Uhrhammer N, Béroud C, Olschwang S. The UMD-APC database, a model of nation-wide knowledge base: update with data from 3,581 variations. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:532–536. doi: 10.1002/humu.22539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papp J, Kovacs ME, Solyom S, Kasler M, Børresen-Dale AL, Olah E. High prevalence of germline STK11 mutations in Hungarian Peutz–Jeghers Syndrome patients. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Q, Li X, Chen JS, Sommer SS (2003) Robust dosage-PCR for detection of heterozygous chromosomal deletions. Biotechniques 34:558–562, 565–566, 568 passim [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Nguyen VQ, Shi J, Liu Q, Sommer SS (2004) Robust dosage (RD)-PCR protocol for the detection of heterozygous deletions. Biotechniques 37:360, 362, 364 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.de Lellis L, Mammarella S, Curia MC, Veschi S, Mokini Z, Bassi C, Sala P, Battista P, Mariani-Costantini R, Radice P, Cama A. Analysis of gene copy number variations using a method based on lab-on-a-chip technology. Tumori. 2012;98:126–136. doi: 10.1177/030089161209800118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi J, Liu Q, Nguyen VQ, Sommer SS. Elimination of locus-specific inter-individual variation in quantitative PCR. Biotechniques. 2004;37:934–938. doi: 10.2144/04376ST01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Nomenclature for the description of human sequence variations. Hum Genet. 2001;109:121–124. doi: 10.1007/s004390100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedl W, Aretz S. Familial adenomatous polyposis: experience from a study of 1164 unrelated german polyposis patients. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2005;3:95–114. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-3-3-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivera B, González S, Sánchez-Tomé E, Blanco I, Mercadillo F, Letón R, Benítez J, Robledo M, Capellá G, Urioste M. Clinical and genetic characterization of classical forms of familial adenomatous polyposis: a Spanish population study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:903–909. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aretz S, Uhlhaas S, Sun Y, Pagenstecher C, Mangold E, Caspari R, Möslein G, Schulmann K, Propping P, Friedl W. Familial adenomatous polyposis: aberrant splicing due to missense or silent mutations in the APC gene. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:370–380. doi: 10.1002/humu.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong JG, Davies DR, Guy SP, Frayling IM, Evans DG. APC mutations in familial adenomatous polyposis families in the Northwest of England. Hum Mutat. 1997;10:376–380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:5<376::AID-HUMU7>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyaki M, Konishi M, Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Enomoto M, Igari T, Tanaka K, Muraoka M, Takahashi H, Amada Y, Fukayama M, et al. Characteristics of somatic mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3011–3020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyoshi Y, Ando H, Nagase H, Nishisho I, Horii A, Miki Y, Mori T, Utsunomiya J, Baba S, Petersen G, et al. Germ-line mutations of the APC gene in 53 familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4452–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fodde R, van der Luijt R, Wijnen J, Tops C, van der Klift H, van Leeuwen-Cornelisse I, Griffioen G, Vasen H, Khan PM. Eight novel inactivating germ line mutations at the APC gene identified by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Genomics. 1992;13:1162–1168. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90032-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jarry J, Brunet JS, Laframboise R, Drouin R, Latreille J, Richard C, Gekas J, Maranda B, Monczak Y, Wong N, Pouchet C, Zaor S, Kasprzak L, Palma L, Wu MK, Tischkowitz M, Foulkes WD, Chong G. A survey of APC mutations in Quebec. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:659–665. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gismondi V, Bafico A, Biticchi R, Pedemonte S, Molina F, Heouaine A, Sala P, Bertario L, Presciuttini S, Strigini P, Groden J, Varesco L. Characterization of 19 novel and six recurring APC mutations in Italian adenomatous polyposis patients, using two different mutation detection techniques. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:370–373. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:4<370::AID-HUMU14>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu G, Wu W, Hegde M, Fawkner M, Chong B, Love D, Su LK, Lynch P, Snow K, Richards CS. Detection of sequence variations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Genet Test. 2001;5:281–290. doi: 10.1089/109065701753617408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobbie Z, Spycher M, Mary JL, Häner M, Guldenschuh I, Hürliman R, Amman R, Roth J, Müller H, Scott RJ. Correlation between the development of extracolonic manifestations in FAP patients and mutations beyond codon 1403 in the APC gene. J Med Genet. 1996;33:274–280. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stella A, Montera M, Resta N, Marchese C, Susca F, Gentile M, Romio L, Pilia S, Prete F, Mareni C, et al. Four novel mutations of the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene in FAP patients. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1687–1688. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.9.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Luijt RB, Khan PM, Vasen HF, Tops CM, van Leeuwen-Cornelisse IS, Wijnen JT, van der Klift HM, Plug RJ, Griffioen G, Fodde R. Molecular analysis of the APC gene in 105 Dutch kindreds with familial adenomatous polyposis: 67 germline mutations identified by DGGE, PTT, and southern analysis. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:7–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:1<7::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim DW, Kim IJ, Kang HC, Park HW, Shin Y, Park JH, Jang SG, Yoo BC, Lee MR, Hong CW, Park KJ, Oh NG, Kim NK, Sung MK, Lee BW, Kim YJ, Lee H, Park JG. Mutation spectrum of the APC gene in 83 Korean FAP families. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:281. doi: 10.1002/humu.9360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norheim Andersen S, Løvig T, Fausa O, Rognum TO. Germline and somatic mutations in exon 15 of the APC gene and K-ras mutations in duodenal adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:611–617. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plawski A, Lubiński J, Banasiewicz T, Paszkowski J, Lipinski D, Strembalska A, Kurzawski G, Byrski T, Zajaczek S, Hodorowicz-Zaniewska D, Gach T, Brozek I, Nowakowska D, Czkwaniec E, Krokowicz P, Drews M, Zeyland J, Juzwa W, Słomski R. Novel germline mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in Polish families with familial adenomatous polyposis. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e11. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.010215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagase H, Nakamura Y. Mutations of the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene. Hum Mutat. 1993;2:425–434. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380020602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mandl M, Paffenholz R, Friedl W, Caspari R, Sengteller M, Propping P. Frequency of common and novel inactivating APC mutations in 202 families with familial adenomatous polyposis. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:181–184. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang J, Papadopoulos N, McKinley AJ, Farrington SM, Curtis LJ, Wyllie AH, Zheng S, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Morin P, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Dunlop MG. APC mutations in colorectal tumors with mismatch repair deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9049–9054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamzehloei T, West SP, Chapman PD, Burn J, Curtis A. Four novel germ-line mutations in the APC gene detected by heteroduplex analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1023–1024. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.6.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mori T, Nagase H, Aoki T, Arakawa H, Nishihira T, Mori S, Nakamura Y. The APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene: a novel mutation in an FAP patient and a DdeI polymorphism in the 5′ noncoding region. Hum Mutat. 1993;2:240–243. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380020315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedl W, Caspari R, Sengteller M, Uhlhaas S, Lamberti C, Jungck M, Kadmon M, Wolf M, Fahnenstich J, Gebert J, Möslein G, Mangold E, Propping P. Can APC mutation analysis contribute to therapeutic decisions in familial adenomatous polyposis? Experience from 680 FAP families. Gut. 2001;48:515–521. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Gregorio C, Frattini M, Maffei S, Ponti G, Losi L, Pedroni M, Venesio T, Bertario L, Varesco L, Risio M, Ponz de Leon M. Immunohistochemical expression of MYH protein can be used to identify patients with MYH-associated polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:439–444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aceto G, Curia MC, Veschi S, De Lellis L, Mammarella S, Catalano T, Stuppia L, Palka G, Valanzano R, Tonelli F, Casale V, Stigliano V, Cetta F, Battista P, Mariani-Costantini R, Cama A. Mutations of APC and MYH in unrelated Italian patients with adenomatous polyposis coli. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:394. doi: 10.1002/humu.9370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Croitoru ME, Cleary SP, Berk T, Di Nicola N, Kopolovic I, Bapat B, Gallinger S. Germline MYH mutations in a clinic-based series of Canadian multiple colorectal adenoma patients. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:499–506. doi: 10.1002/jso.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S, Pagenstecher C, Mangold E, Caspari R, Propping P, Friedl W. Large submicroscopic genomic APC deletions are a common cause of typical familial adenomatous polyposis. J Med Genet. 2005;42:185–192. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.022822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michils G, Tejpar S, Thoelen R, van Cutsem E, Vermeesch JR, Fryns JP, Legius E, Matthijs G. Large deletions of the APC gene in 15% of mutation-negative patients with classical polyposis (FAP): a Belgian study. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:125–134. doi: 10.1002/humu.20122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gómez-Fernández N, Castellví-Bel S, Fernández-Rozadilla C, Balaguer F, Muñoz J, Madrigal I, Milà M, Graña B, Vega A, Castells A, Carracedo A, Ruiz-Ponte C. Molecular analysis of the APC and MUTYH genes in Galician and Catalonian FAP families: a different spectrum of mutations? BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lagarde A, Rouleau E, Ferrari A, Noguchi T, Qiu J, Briaux A, Bourdon V, Rémy V, Gaildrat P, Adélaïde J, Birnbaum D, Lidereau R, Sobol H, Olschwang S. Germline APC mutation spectrum derived from 863 genomic variations identified through a 15-year medical genetics service to French patients with FAP. J Med Genet. 2010;47:721–722. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.078964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giarola M, Stagi L, Presciuttini S, Mondini P, Radice MT, Sala P, Pierotti MA, Bertario L, Radice P. Screening for mutations of the APC gene in 66 Italian familial adenomatous polyposis patients: evidence for phenotypic differences in cases with and without identified mutation. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:116–123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:2<116::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wallis YL, Morton DG, McKeown CM, Macdonald F. Molecular analysis of the APC gene in 205 families: extended genotype–phenotype correlations in FAP and evidence for the role of APC amino acid changes in colorectal cancer predisposition. J Med Genet. 1999;36:14–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kanter-Smoler G, Fritzell K, Rohlin A, Engwall Y, Hallberg B, Bergman A, Meuller J, Grönberg H, Karlsson P, Björk J, Nordling M. Clinical characterization and the mutation spectrum in Swedish adenomatous polyposis families. BMC Med. 2008;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andresen PA, Heimdal K, Aaberg K, Eklo K, Ariansen S, Silye A, Fausa O, Aabakken L, Aretz S, Eide TJ, Gedde-Dahl T., Jr APC mutation spectrum of Norwegian familial adenomatous polyposis families: high ratio of novel mutations. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:1463–1470. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0594-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takahashi M, Kikuchi M, Ohkura N, Yaguchi H, Nagamura Y, Ohnami S, Ushiama M, Yoshida T, Sugano K, Iwama T, Kosugi S, Tsukada T. Detection of APC gene deletion by double competitive polymerase chain reaction in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kovacs ME, Papp J, Szentirmay Z, Otto S, Olah E. Deletions removing the last exon of TACSTD1 constitute a distinct class of mutations predisposing to Lynch syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:197–203. doi: 10.1002/humu.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP, Chan TL, Goossens M, Hebeda KM, Voorendt M, Lee TY, Bodmer D, Hoenselaar E, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, Tsui WY, Kong CK, Brunner HG, van Kessel AG, Yuen ST, van Krieken JH, Leung SY, Hoogerbrugge N. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3′ exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet. 2009;41:112–117. doi: 10.1038/ng.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kempers MJ, Kuiper RP, Ockeloen CW, Chappuis PO, Hutter P, Rahner N, Schackert HK, Steinke V, Holinski-Feder E, Morak M, Kloor M, Büttner R, Verwiel ET, van Krieken JH, Nagtegaal ID, Goossens M, van der Post RS, Niessen RC, Sijmons RH, Kluijt I, Hogervorst FB, Leter EM, Gille JJ, Aalfs CM, Redeker EJ, Hes FJ, Tops CM, van Nesselrooij BP, van Gijn ME, Gómez García EB, Eccles DM, Bunyan DJ, Syngal S, Stoffel EM, Culver JO, Palomares MR, Graham T, Velsher L, Papp J, Oláh E, Chan TL, Leung SY, van Kessel AG, Kiemeney LA, Hoogerbrugge N, Ligtenberg MJ. Risk of colorectal and endometrial cancers in EPCAM deletion-positive Lynch syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:49–55. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chuzhanova N, Abeysinghe SS, Krawczak M, Cooper DN. Translocation and gross deletion breakpoints in human inherited disease and cancer II: potential involvement of repetitive sequence elements in secondary structure formation between DNA ends. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:245–251. doi: 10.1002/humu.10253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abeysinghe SS, Chuzhanova N, Krawczak M, Ball EV, Cooper DN. Translocation and gross deletion breakpoints in human inherited disease and cancer I: nucleotide composition and recombination-associated motifs. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:229–244. doi: 10.1002/humu.10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abeysinghe SS, Stenson PD, Krawczak M, Cooper DN. Gross Rearrangement Breakpoint Database (GRaBD) Hum Mutat. 2004;23:219–221. doi: 10.1002/humu.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Korbel JO, Urban AE, Affourtit JP, Godwin B, Grubert F, Simons JF, Kim PM, Palejev D, Carriero NJ, Du L, Taillon BE, Chen Z, Tanzer A, Saunders AC, Chi J, Yang F, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Weissman SM, Harkins TT, Gerstein MB, Egholm M, Snyder M. Paired-end mapping reveals extensive structural variation in the human genome. Science. 2007;318:420–426. doi: 10.1126/science.1149504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Quadri M, Vetro A, Gismondi V, Marabelli M, Bertario L, Sala P, Varesco L, Zuffardi O, Ranzani GN. APC rearrangements in familial adenomatous polyposis: heterogeneity of deletion lengths and breakpoint sequences underlies similar phenotypes. Fam Cancer. 2015;14:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s10689-014-9750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miki Y, Nishisho I, Miyoshi Y, Horii A, Ando H, Nakajima T, Utsunomiya J, Nakamura Y. Frequent loss of heterozygosity at the MCC locus on chromosome 5q21-22 in sporadic colorectal carcinomas. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:1003–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb01935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fukuyama R, Niculaita R, Ng KP, Obusez E, Sanchez J, Kalady M, Aung PP, Casey G, Sizemore N. Mutated in colorectal cancer, a putative tumor suppressor for serrated colorectal cancer, selectively represses beta-catenin-dependent transcription. Oncogene. 2008;27:6044–6055. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Out AA, Tops CM, Nielsen M, Weiss MM, van Minderhout IJ, Fokkema IF, Buisine MP, Claes K, Colas C, Fodde R, Fostira F, Franken PF, Gaustadnes M, Heinimann K, Hodgson SV, Hogervorst FB, Holinski-Feder E, Lagerstedt-Robinson K, Olschwang S, van den Ouweland AM, Redeker EJ, Scott RJ, Vankeirsbilck B, Grønlund RV, Wijnen JT, Wikman FP, Aretz S, Sampson JR, Devilee P, den Dunnen JT, Hes FJ. Leiden open variation database of the MUTYH gene. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1205–1215. doi: 10.1002/humu.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Friedl W, Meuschel S, Caspari R, Lamberti C, Krieger S, Sengteller M, Propping P. Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis due to a mutation in the 3′ part of the APC gene. A clue for understanding the function of the APC protein. Hum Genet. 1996;97:579–584. doi: 10.1007/BF02281864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brensinger JD, Laken SJ, Luce MC, Powell SM, Vance GH, Ahnen DJ, Petersen GM, Hamilton SR, Giardiello FM. Variable phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis in pedigrees with 3′ mutation in the APC gene. Gut. 1998;43:548–552. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Soravia C, Berk T, Madlensky L, Mitri A, Cheng H, Gallinger S, Cohen Z, Bapat B. Genotype–phenotype correlations in attenuated adenomatous polyposis coli. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1290–1301. doi: 10.1086/301883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertario L, Russo A, Sala P, Varesco L, Giarola M, Mondini P, Pierotti M, Spinelli P, Radice P, Hereditary Colorectal Tumor Registry Multiple approach to the exploration of genotype–phenotype correlations in familial adenomatous polyposis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1698–1707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nielsen M, Hes FJ, Nagengast FM, Weiss MM, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Morreau H, Breuning MH, Wijnen JT, Tops CM, Vasen HF. Germline mutations in APC and MUTYH are responsible for the majority of families with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Genet. 2007;71:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Filipe B, Baltazar C, Albuquerque C, Fragoso S, Lage P, Vitoriano I, Mão de Ferro S, Claro I, Rodrigues P, Fidalgo P, Chaves P, Cravo M, Nobre Leitão C. APC or MUTYH mutations account for the majority of clinically well-characterized families with FAP and AFAP phenotype and patients with more than 30 adenomas. Clin Genet. 2009;76:242–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Palles C, Cazier JB, Howarth KM, Domingo E, Jones AM, Broderick P, Kemp Z, Spain SL, Guarino E, Salguero I, Sherborne A, Chubb D, Carvajal-Carmona LG, Ma Y, Kaur K, Dobbins S, Barclay E, Gorman M, Martin L, Kovac MB, Humphray S, CORGI Consortium. WGS500 Consortium. Lucassen A, Holmes CC, Bentley D, Donnelly P, Taylor J, Petridis C, Roylance R, Sawyer EJ, Kerr DJ, Clark S, Grimes J, Kearsey SE, Thomas HJ, McVean G, Houlston RS, Tomlinson I. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:136–144. doi: 10.1038/ng.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weren RD, Ligtenberg MJ, Kets CM, de Voer RM, Verwiel ET, Spruijt L, van Zelst-Stams WA, Jongmans MC, Gilissen C, Hehir-Kwa JY, Hoischen A, Shendure J, Boyle EA, Kamping EJ, Nagtegaal ID, Tops BB, Nagengast FM, Geurts van Kessel A, van Krieken JH, Kuiper RP, Hoogerbrugge N. A germline homozygous mutation in the base-excision repair gene NTHL1 causes adenomatous polyposis and colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:668–671. doi: 10.1038/ng.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tuohy TM, Done MW, Lewandowski MS, Shires PM, Saraiya DS, Huang SC, Neklason DW, Burt RW. Large intron 14 rearrangement in APC results in splice defect and attenuated FAP. Hum Genet. 2010;127:359–369. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0776-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spier I, Horpaopan S, Vogt S, Uhlhaas S, Morak M, Stienen D, Draaken M, Ludwig M, Holinski-Feder E, Nöthen MM, Hoffmann P, Aretz S. Deep intronic APC mutations explain a substantial proportion of patients with familial or early-onset adenomatous polyposis. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1045–1050. doi: 10.1002/humu.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pavicic W, Nieminen TT, Gylling A, Pursiheimo JP, Laiho A, Gyenesei A, Järvinen HJ, Peltomäki P. Promoter-specific alterations of APC are a rare cause for mutation-negative familial adenomatous polyposis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:857–864. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shirts BH, Salipante SJ, Casadei S, Ryan S, Martin J, Jacobson A, Vlaskin T, Koehler K, Livingston RJ, King MC, Walsh T, Pritchard CC. Deep sequencing with intronic capture enables identification of an APC exon 10 inversion in a patient with polyposis. Genet Med. 2014;16:783–786. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Snow AK, Tuohy TM, Sargent NR, Smith LJ, Burt RW, Neklason DW. APC promoter 1B deletion in seven American families with familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1111/cge.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]