Abstract

The experience of child maltreatment is a significant risk factor for the development of later internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety. This risk is particularly heightened after exposure to additional, more contemporaneous stress. While behavioral evidence exists for such “stress sensitization,” little is known about the mechanisms mediating such relationships, particularly within the brain. Here we report that the experience of child maltreatment independent of recent life stress, gender, and age is associated with reduced structural integrity of the uncinate fasciculus, a major white matter pathway between the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, in young adults. We further demonstrate that individuals with lower uncinate fasciculus integrity at baseline who subsequently experience stressful life events report higher levels of internalizing symptomatology at follow-up. Our findings suggest a novel neurobiological mechanism linking child maltreatment with later internalizing symptoms, specifically altered structural connectivity within the brain’s threat-detection and emotion regulation circuitry.

Unfortunately, 1 in 8 children in the United States will experience some form of maltreatment by 18 years of age (Wildeman et al., 2014). Such adversities represent a severe hazard to the development of an individual and particularly alarming, child maltreatment is related to a 60–70% increase risk for lifetime mood and anxiety disorders (Chapman et al., 2004; Danese et al., 2009; Green et al., 2010; McLaughlin et al., 2013). Though well-studied and well-replicated in psychological and epidemiological research, the exact mechanisms mediating the association between maltreatment and later internalizing disorders remain unclear.

Suggestive from investigations focused on multiple levels of analysis is that this risk may be conferred by altered responses to later, more contemporaneous, stressful experiences. For example, maltreatment alters psychological processes after acute stress, as those who suffer such adversity report greater negative affect after subsequent stress (Glaser, van Os, Portegijs, & Myin-Germeys, 2006) and also poorer emotion regulation including less emotional self-awareness (Herts, McLaughlin, & Hatzenbuehler, 2012; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010). Direct examination of this “stress sensitization” has supported these ideas, as recent stress after child maltreatment has been found to predict subsequent increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as clinical disorder after exposure to stress later in life (Espejo et al., 2007; Hammen, Henry, & Daley, 2000; Harkness, Bruce, & Lumley, 2006; McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010; Shapero et al., 2013). Hammen and colleagues (2000) found that women with exposure to childhood adversities had a lower threshold for developing a depressive reaction to stressors. Shapero et al. (2013) noted comparable results, finding that individuals with more severe childhood emotional abuse experienced greater increases in depressive symptoms when confronted with current stressors. McLaughlin and coworkers (2010) extended these investigations to examine risk of major depression and also anxiety disorders, finding that the risk for psychopathology after past-year major stressors was nearly doubled for individuals with a history of childhood adversity compared to those without such a history.

Implicit in these “stress sensitization” studies is that vulnerability to depression and anxiety involves interactions among numerous processes at the neurobiological, environmental, and psychosocial levels. While research has focused on environmental and psychosocial factors, less work has centered on neurobiological processes. Preliminary evidence has found that child maltreatment and other types of early adversity increases reactivity to acute stress through physiological pathways, such as alterations in blood pressure (Gooding, Milliren, Austin, Sheridan, & McLaughlin, 2015; Leitzke, Hilt, & Pollak, 2015), cardiac output (McLaughlin, Sheridan, Alves, & Mendes, 2014), and cortisol release (Heim, Newport, Mletzko, Miller, & Nemeroff, 2008; Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006). Limited work, to date, has examined how this “stress sensitization” may be related to alterations in the brain, which mediates the effects of external stressors on internal physiological states. Thus, identifying the impact of child maltreatment on the brain directly will deepen basic knowledge of how such adversity can become embedded in our physiology and behavior. In addition, understanding how differences in the brain interact with environmental and psychosocial factors could also inform the search for strategies to offset the negative sequelae of child maltreatment leading to resiliency and greater wellbeing.

Prior research has identified a number of candidate structures in the brain that may be both centrally involved in the pathophysiology of internalizing psychopathology and sensitive to early life stress. Of particular note are two nodes within a distributed corticolimbic circuit supporting recognition and reaction to threat: the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). The amygdala is an information-processing hub, supporting both physiological (e.g., autonomic reactivity) and behavioral (e.g., reallocation of attentional resources) responses to environmental and social challenges (Davis & Whalen, 2001; Hariri, 2009; Ledoux, 2000). These responses are subsequently integrated and regulated through activity of the vmPFC, which has extensive reciprocal connections with the amygdala (Bishop, 2007; Davidson, Putnam, & Larson, 2000; Ghashghaei & Barbas, 2002; Milad & Quirk, 2012; Quirk & Beer, 2006). A number of investigations have begun to link different forms of maltreatment with alterations in the structure and function of the amygdala and vmPFC (Dannlowski et al., 2012; De Brito et al., 2013; Hanson et al., 2010; 2015; Tottenham et al., 2011). Relatively few investigations have, however, considered the relationship between maltreatment and the structural connections between these nodes.

The uncinate fasciculus (UF) is a major white matter tract that connects the amygdala to the vmPFC as well as other subregions of the PFC involved in top-down regulation of amygdala activity (Amaral & Price, 1984; Barbas & De Olmos, 1990; Morecraft, Geula, & Mesulam, 1992; Petrides & Pandya, 1988; Porrino, Crane, & Goldman-Rakic, 1981). The structural integrity of the UF may thus be particularly important to consider in relation to child maltreatment, stress-sensitization, and later internalizing psychopathology. In fact, lower uncinate fasciculus FA has been observed in children exposed to early social neglect (Eluvathingal et al., 2006; Govindan, Behen, Helder, Makki, & Chugani, 2010). However, other studies have not found evidence for similar alterations (Choi, Jeong, Polcari, Rohan, & Teicher, 2012; Choi, Jeong, Rohan, Polcari, & Teicher, 2009; Huang, Gundapuneedi, & Rao, 2012). These inconsistent results may reflect generally small and thus underpowered sample sizes or relatively crude group comparisons between maltreated and non-maltreated individuals.

Here, we examined associations between a continuous measure of self-reported experience of child maltreatment and uncinate fasciculus FA in 848 young adult university students. We further explored the extent to which alterations in uncinate fasciculus FA associated with child maltreatment were expressed as self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. Finally, consistent with the “stress sensitization” model we tested if uncinate fasciculus FA predicted the subsequent experience of these symptoms following stressful life events. We hypothesized that child maltreatment would be associated with reduced uncinate fasciculus FA in young adulthood and that reduced uncinate fasciculus FA would be associated with higher internalizing symptomatology as well as increased vulnerability to future life stress.

Method

Participants

A total of 848 participants (Initial Age Range: 18–22 years old) were included from the ongoing Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS), which assesses a wide range of behavioral and biological traits among non-patient, young adolescent and adult student volunteers. This study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. Participants were excluded in the present sample if they met the following criteria: (1) medical diagnoses of cancer, stroke, diabetes requiring insulin treatment, chronic kidney or liver disease, or lifetime history of psychotic symptoms; (2) use of psychotropic, glucocorticoid, or hypolipidemic medication; and/or (3) conditions affecting cerebral blood flow and metabolism (e.g. hypertension); and (4) met quality control criteria for MRI scanning. Diagnosis of any current DSM-IV Axis I disorder or select Axis II disorders (antisocial personality disorder; borderline personality disorder), were assessed with the electronic Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) and Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV subtests (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). Such diagnoses were, however, not an exclusion criteria, as the DNS seeks to establish broad variability in multiple behavioral phenotypes related to psychopathology. One hundred and sixty-seven subjects met criteria for having a current or past one Axis I disorder, including alcohol dependence (n=43), alcohol abuse (n=53), any type of anxiety disorder (n=39) or any type of major depressive disorder (n=28). Three participants met criteria for at least one Axis II disorder (Anti-social Personality Disorder n=1; Borderline Personality Disorder n=2).

All successful DNS participants were then contacted every 3 months after initial study completion and asked to complete a brief online assessment of recent life events, mood, and affect in the past week. Secondary longitudinal analyses were restricted to a subset of 378 participants that completed these follow-up measures at least 6 months after their MRI scanning (mean time since scan = 313.6 ± 166.38 days, at the time of follow-up). Additional demographic information for the full sample and longitudinal subsample are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Information: Full Sample

| Variable | Distribution (Mean ± Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Gender | 365 Male, 483 Female |

| Age | 19.62 ± 1.25 years |

| Race | 422 Caucasian, 230 Asian, 104 African American/Black, 63 Bi- or Multiracial, 26 Other, 3 Native American |

| Child Maltreatment (CTQ) | 33.62 ± 8.52 |

| Recent Life Stress (LESS Total Events) | 4.419 ± 3.20 |

| Internalizing Symptomatology (Total MASQ Score) | 108.81 ± 24.52 |

Table 2.

Demographic Information: Longitudinal Subsample

| Variable | Distribution (Mean ± Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Gender | 138 Male, 240 Female |

| Age | 19.53 ± 1.2 years |

| Race | 205 Caucasian, 94 Asian, 37 African American/Black, 26 Bi- or Multiracial, 15 Other, 1 Native American |

| Child Maltreatment (CTQ) | 33.14 ± 8.26 |

| Recent Life Stress (LESS Total Events) | 1.80 ± 1.99 |

| Internalizing Symptomatology (Total MASQ Score) | 111.27 ± 27.17 |

| Days Since MRI Scan | 313.63 ± 166.38 |

Procedures

Participants were recruited through posting on various university-related electronic mailing lists, flyers posted around the area, and our laboratory’s website (http://www.haririlab.com/brain.php). This final recruitment source contained electronic screening forms and has been visited over 7,000 times to date. Once identified, adolescent and young adult participants came to our university-based laboratory to participate in the study. We collected MRI measures to assess neurobiology, specifically well-validated neuroimaging measures of structural connectivity. At the time of scanning, participants reported the number of stressful life events they had experienced in the prior year, as well as experiences of child maltreatment. Participants also reported on current levels of internalizing symptomatology. Individuals received an honorarium of $120 for completion of this initial study visit. After successful completion of the baseline protocol including MRI scan, all participants were subsequently contacted by e-mail every 3 months and invited to complete a short online assessment of their current mood and experience of stressful life events since their last assessment. Participants who completed this post-scanning follow-up were then entered into a raffle for a $50 gift card at each round of follow-up assessment.

Self-Report Questionnaires

Participants completed a battery of self-report questionnaires to assess past and current experiences and behavior. The following were used for the present analyses: the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997); Life Events Scale for Students (LESS; Clements & Turpin, 1996); the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire- short form (MASQ-SF; Clark & Watson, 1991).

The CTQ is a 28-item, retrospective screening tool used to assess exposure to childhood maltreatment in five categories: emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect. Each of the CTQ’s five subscales has robust internal consistency and convergent validity with a clinician-rated interview of childhood abuse and therapists’ ratings of abuse (Fink, Bernstein, Handelsman, Foote, & Lovejoy, 1995). Scores on each subscale (range: 5–25) were summed to provide a total score (range in DNS: 25–75; mean= 33.62 +/−8.52). This instrument and approach has been employed in other recent research studies focused on child maltreatment (Gorka, Hanson, Radtke, & Hariri, 2014; Herringa et al., 2013; Teicher, Anderson, & Polcari, 2012). To assess the occurrence of common stressful life events within the past 12 months, we used a modified version of the LESS. In this checklist, participants indicated which stressful life events happened to them over the past year (e.g., broke up with romantic partner, failed a course, family health problems, financial problems). Recent symptoms of internalizing psychopathology were assessed using the MASQ. The MASQ is a well-validated measure, yielding four subscales assessing symptoms experienced within the last 7 days specific to anxious arousal and anhedonic depression, as well as general anxiety and general depression. In line with past research (Swartz, Knodt, Radtke, & Hariri, 2015), these four subscales were summed to create a measure of total internalizing symptoms.

MRI Data Acquisition And Processing

Each participant was scanned on one of two identical research-dedicated GE MR750 3T scanners at the Duke-UNC Brain Imaging and Analysis Center. Each identical scanner was equipped with high-power high-duty cycle 50-mT/m gradients at 200 T/m/s slew rate and an eight-channel head coil for parallel imaging at high bandwidth up to 1 MHz. Following an ASSET calibration scan, two 2-min 50-s high angular resolution diffusion imaging acquisitions were collected, providing full brain coverage with 2-mm isotropic resolution and 15 diffusion weighted directions (10-s repetition time, 84.9 ms echo time, b value 1,000 s/mm2, 240 mm field of view, 90° flip angle, 128 × 128 acquisition matrix, slice thickness=2 mm). High resolution T1-weighted images were also obtained using a 3D Ax FSPGR BRAVO sequence with the following parameters: TR =8.148 s; TE =3.22 ms; 162 sagittal slices; flip angle, 12°; FOV, 240 mm; matrix =256 × 256; slice thickness =1 mm with no gap; and total scan time =4 minutes and 13 seconds.

Diffusion tensor images were processed according to the protocol developed by the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta-Analysis (Jahanshad et al., 2013 or http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/dti-protocols/). In brief, raw diffusion-weighted images underwent eddy current correction and linear registration to the non-diffusion weighted image in order to correct for head motion. These images were skull-stripped and diffusion tensor models were fit at each voxel using in FMRIB's Diffusion Toolbox (FDT; http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FDT). This produced a whole-brain fractional anisotropy (FA) image for each participant which was next processed using tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) in FMRIB's Software Library (FSL; Smith et al., 2006). FA images were realigned to the FMRIB standard-space FA image and transformed into MNI standard space. A mean FA skeleton was created and thresholded at .2 and each participant's FA data were projected onto the skeleton. Regions of interest were then created using the Johns Hopkins University White Matter Tractography Atlas (Mori, Wakana, Van Zijl, & Nagae-Poetscher, 2005). The left and right uncinate fasciculus regions were binarized and skeletonized in order to extract mean FA values from the left uncinate fasciculus (UF) and right uncinate fasciculus for each participant. Whole brain average FA values were also calculated to include all voxels in the ENIGMA-DTI skeleton and included in all analyses as a covariate of no interest.

Statistical Analyses

Relationships between child maltreatment and internalizing symptomatology were first examined using linear regression models. For these statistical analyses, a composite internalizing measure (total score from the MASQ at initial assessment) was entered as the dependent variable and age (in years), gender (entered as a dummy-coded factor), recent stressful life events, and CTQ total scores were entered as our independent variables. Of note, recent stressful life events were entered in these models to ensure that any results were unique to exposure to child maltreatment. To examine associations between structural connectivity and child maltreatment, we first constructed linear regression models with FA values for the left or right UF entered as dependent variables (in separate regressions) and whole-brain average FA, age (in years), gender (entered as a dummy-coded factor), recent stressful life events, and CTQ total scores were entered as our independent variables. Again, recent stressful life events were entered in these analyses to ensure specificity of our results for maltreatment. Additional analyses also sought to rule out the effects of past and present psychopathology in our sample. To these ends, supplemental analyses were conducted with a binary-coded covariate noting the presence of psychopathology (0=no history of psychopathology; 1=current or past psychopathology). To examine relationships between structural connectivity and internalizing symptoms, we next constructed linear regression models with our composite internalizing measure (total score from the MASQ) entered as the dependent variable. For these models, whole-brain average FA, age (in years), gender (as a dummy-coded factor), and FA values for the left or right UF (in separate regressions) were entered as our independent variables. Supplemental analyses were again conducted with a binary-coded covariate noting the presence of psychopathology.

Using data from our longitudinal subsample, linear regression models were also employed to investigate the extent to which UF structural integrity (as measured by FA), child maltreatment, recent life stress, or their interactions influenced self-reports of internalizing symptomatology. For these analyses, total score from the MASQ at follow-up was entered as the dependent variable, while whole-brain average FA at baseline, age at baseline and at follow-up (in years), gender (entered as a dummy-coded factor), total score from the MASQ at baseline, number of days since the neuroimaging session, recent stressful life events at baseline and at follow-up, CTQ total scores, UF FA, and interaction terms for recent stress, CTQ, and UF FA (two and three-way interactions) were entered as independent variables All predictor variables were mean-centered prior to analyses and their product terms were computed using these standardized variables to minimize multi-collinearity. All analyses were completed using the R statistical package (R Core Team, 2014) and tests of significance were conducted at conventional alpha (p< 0.05, two-tailed).

Results

Sample Demographics

For the CTQ total scores, the full-sample mean was 33.63 (standard deviation=8.52) and the range was 25–75, with a score of 25 being the lowest possible sum (with a participant selecting a “1 = Never True” for all items). These values are similar to previous research with adolescents and young adults in a community sample (Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary, & Forde, 2001). Similar to previous research with adolescents and young adults (Covault et al., 2007), our participants reported an average of 4.42 recent stressful life events. For the MASQ, the means and standard deviations for the total score were again similar to previous reports from adolescents and young adults (mean = 108.81, sd= 24.52; range: 60–245) (Bogdan, Perlis, Fagerness, & Pizzagalli, 2010). In line with past reports and central to our questions of interest, CTQ total scores were positively correlated with total internalizing symptomatology (β=0.429, p<0.005) as assessed by the MASQ. None of the self-report measures differed between men and women (all ps > 0.4).

Structural Connectivity, Child Maltreatment, and Internalizing Symptomatology (Full Sample)

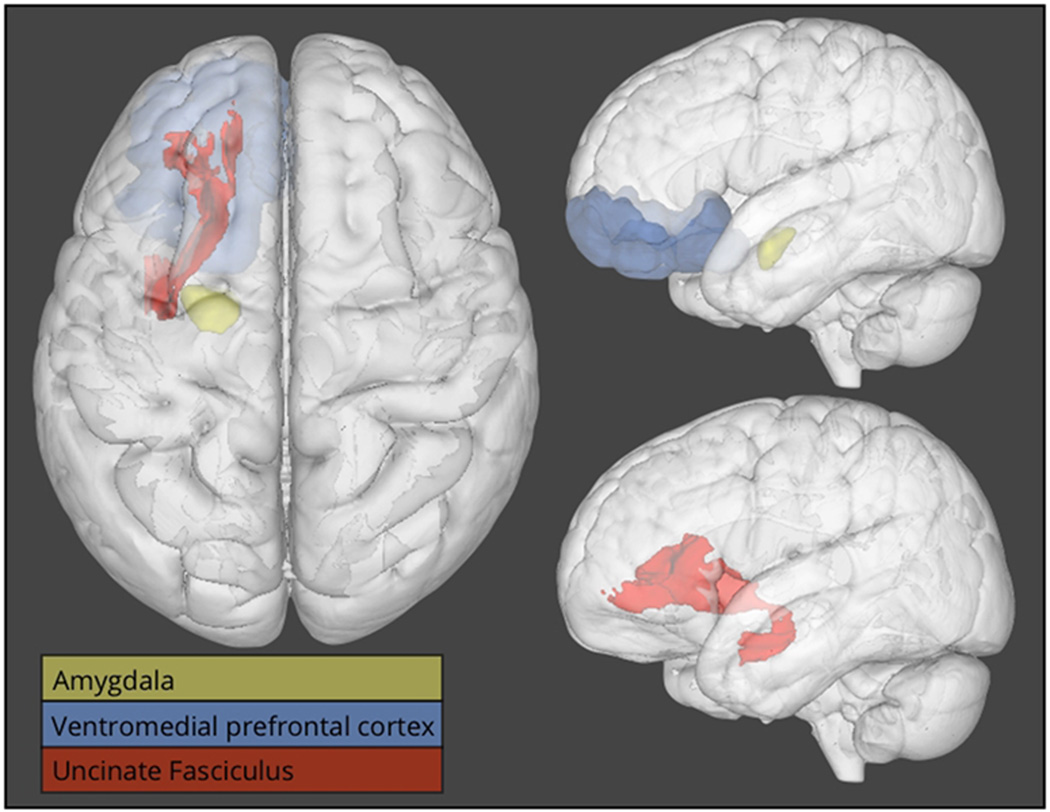

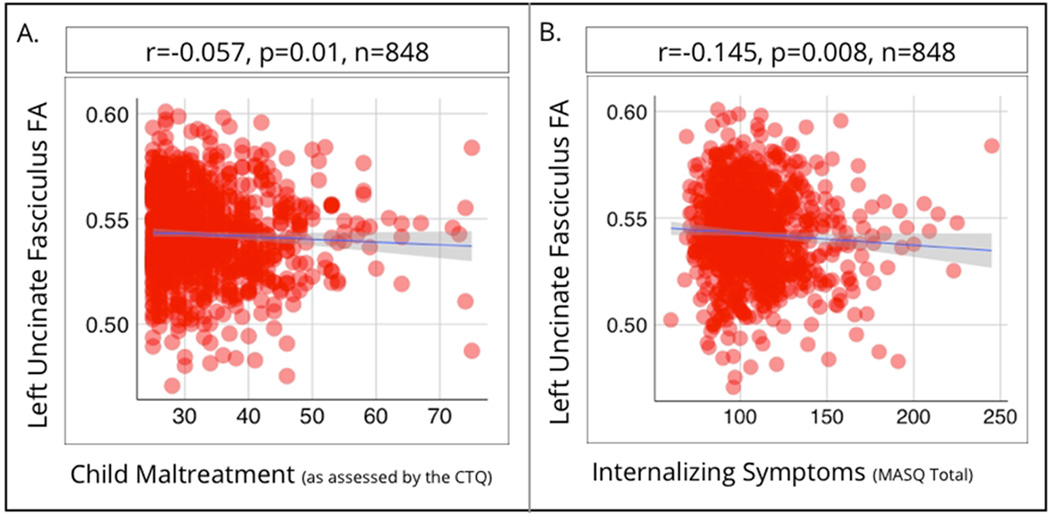

As predicted, childhood maltreatment was related to vmPFC-amygdala structural connectivity, with greater CTQ scores associated with lower FA in the left UF (β=−0.057, p= 0.013). This white matter pathway is shown in Figure 1, in relation to the vmPFC and amygdala. Importantly, this relationship was seen after controlling for recent life stress exposure, gender, and age (Scatterplot shown in Figure 2a). This relationship remained significant if the presence of psychopathology was controlled for (β=−0.055, p=0.013). There was no association between childhood maltreatment and FA in the right UF (β=−0.022, p=0.38). Individual differences in left UF FA were associated with self-reports of internalizing problems, with lower FA related to greater (β=−0.145, p=0.009; Figure 2b). This relationship remained significant if the presence of psychopathology was controlled for (β=−0.15, p< 0.005).

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional overlays displaying the uncinate fasciculus (in red), the amygdala (in yellow), and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (in blue). The left side of the figure depicts a view looking down from the top of the head (analogous to axial orientation). The right side of the figure depicts a view from the side of the head (analogous to sagittal orientation). The amygdala (in yellow) and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (in blue) are shown in the top right corner, while the uncinate fasciculus (in red) is shown in isolation in the bottom right panel.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots showing fractional anisotropy of the left uncinate fasciculus (vertical axis; in both panels) and child maltreatment (horizontal axis; panel a) and internalizing symptomatology (horizontal axis; panel b).

Structural Connectivity, Stress Exposure, and Later Internalizing Symptomatology (longitudinal sample)

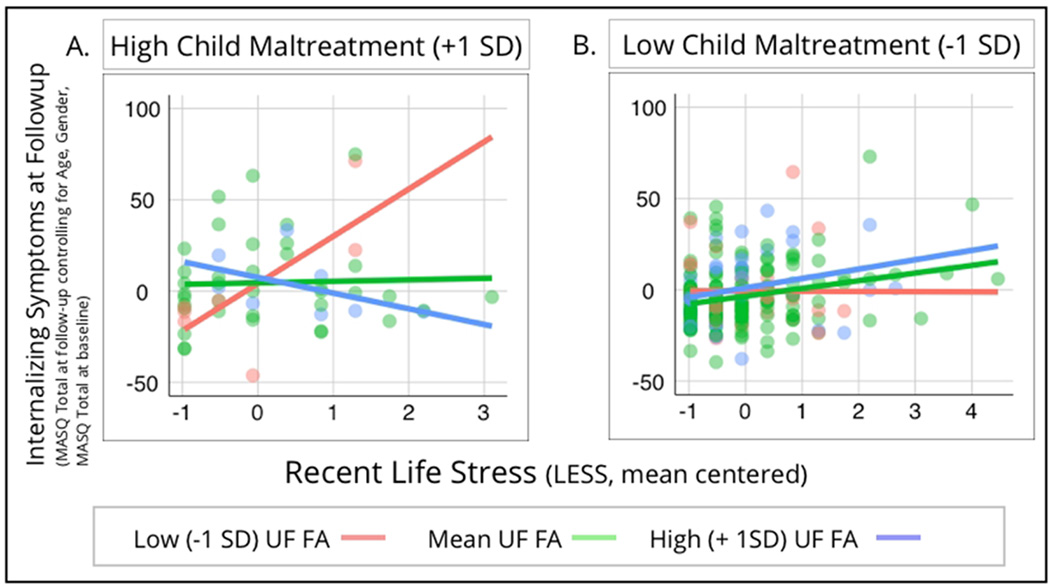

In regards to recent stress exposure and subsequent internalizing symptomatology, similar to past reports we found a significant positive correlation between recent stressful life events and MASQ total scores at follow-up (β=0.213, p<0.005). Reports of child maltreatment at baseline were also related to MASQ total scores at follow-up (β=0.235, p<.005). Of important note, these analyses controlled for a number of potential confounds including gender, age at baseline and follow-up, initial internalizing problems, days since initial assessment, and recent stress exposure at baseline. Central to our question of interest, there was a significant three-way interaction between UF FA, child maltreatment, and recent stressful life events (β=−0.11, p=0.01). As shown in Figure 3, UF FA moderated the relationship between recent stressful life events and MASQ total scores at follow-up, but this was only seen in participants with higher reports of child maltreatment. The interaction of UF FA and recent stressful life events was only significantly different for participants with higher reports of child maltreatment (+1 SD on the CTQ; n=52; p=0.0038). All other interactions were non-significant. Our three-way interaction remained significant if the presence of psychopathology was controlled for (β=−0.11, p=0.01) or using robust regression techniques (B=−3.55, SE=1.16, t=−3.04).

Figure 3.

Scatterplots showing the relationship between recent life stress (as measured by the LESS) and internalizing symptoms measured at least 6 months after initial assessment (as measured by the total score on the MASQ at follow-up; controlling for age, gender, and total MASQ at baseline). This is plotted at low (−1 SD), intermediate (mean), and high (+1 SD) levels of left uncinate fasciculus fractional anisotropy, for those with high reports of child maltreatment (panel a, left side of the figure) and also low reports of child maltreatment (panel b, right side of the figure).

Discussion

Our data reveal that child maltreatment is associated with reduced fractional anisotropy of the uncinate fasciculus, which in turn predicts symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as psychological vulnerability to future life stress. Collectively, our results suggest a novel neurobiological mechanism linking childhood experiences of maltreatment with later internalizing symptoms, specifically altered structural connectivity within the brain’s threat-detection and emotion regulation circuitry. This risk is most strongly evident when individuals are exposed to increasing amounts of contemporaneous stress.

Our findings are consistent with earlier work reporting decreased uncinate fasciculus FA in institutionalized children facing a lack of toys or stimulation, unresponsive caregiving, and an overall dearth of individualized care and attention (Rutter, 1998). Our large sample size and use of a continuous measure of maltreatment likely allowed for the detection of significant associations with more modest levels of maltreatment. Our findings are further consistent with past reports of lower FA in the UF in major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders as well as in individuals with higher trait anxiety. Reduced structural integrity of the UF (as indexed by lower FA) may result in a diminished vmPFC inhibition of responses to environmental threats and other negatively-valenced stimuli. Investigations employing both DTI and functional MRI methods have supported this idea, with lower FA in the UF relating to reduced functional connectivity between portions of the prefrontal cortex and amygdala (Etkin, Prater, Hoeft, Menon, & Schatzberg, 2010; Tromp et al., 2012). With internalizing psychopathology often being preceded by life events that possess a high degree of threat and unpleasantness (Hammen, 2005; Kessler, 1997; Monroe & Reid, 2008; Paykel, 2003), effective regulation of negative emotion, specifically through vmPFC-amygdala pathways, is critical to preventing increases in symptoms of depression or anxiety.

The results presented here also suggest new avenues of investigation, particularly in the development and refinement of interventions to promote resilience. Tracking when neurobiological differences related to maltreatment emerge in development could indicate critical or sensitive periods when treatments may be more effective. Furthermore, it may be possible to tailor psychological interventions based on differences in neurobiology; for example, recent research in treatments for depression have found brain activity pre-treatment differentiated which individuals would have positive outcomes for cognitive behavioral- or pharmaco-therapy (McGrath et al., 2013). Neurobiological data could also be used as a marker of early treatment efficacy. Differences may emerge at a neurobiological level, earlier during an intervention that forecast later positive psychological outcomes.

Our work is not without limitations. First, our study is not a true community sample instead drawing from a university population. Participants could be considered resilient, yet significant associations between neurobiology and maltreatment were still detected in these individuals. Our study therefore likely under-represents the true effects of maltreatment. Second, only one neuroimaging time point was available for our analyses. With the pathways to either maladaptive or positive adaptive functioning being influenced by a complex matrix of factors (Cicchetti & Tucker, 1994), additional research with longitudinal measures of both brain and behavior are needed. Such work could elucidate how neurobiological, environmental, and psychosocial factors continue to interact and potentially amplify (or diminish) risk over development. Related to this, it is possible that some of our participants will go on to develop psychopathology later in their lifetime, with the median onset of mood disorders such as major depression being between 25–30 years of age (K. C. Burke, Burke, Regier, & Rae, 1990; Kessler et al., 2005). Understanding different profiles of individuals at different developmental periods is critical to fostering resilience in maltreated children, adolescents, and adults. Third, we only focused on one developmental outcome: internalizing symptomatology. With maltreated individuals rarely manifesting competence across all developmental domains, a broader multilevel approach to risk and resilience could increase knowledge about the full sequelae of maltreatment (Cicchetti & Gunnar, 2008; Walsh, Dawson, & Mattingly, 2010). For example, externalizing problems may relate to vmPFC-amygdala circuitry (McCrory & Viding, 2015). Alternatively, alterations in vmPFC-amygdala circuitry may cause increasing symptoms of depression or anxiety, and then these problems lead to rule breaking, aggression, and other behavioral problems over the course of development. Finally, our measure of child maltreatment, the CTQ does not richly assess factors of this adversity likely to influence outcomes. Information about the subtype of maltreatment suffered, severity, frequency/chronicity, developmental period during which these experiences occurred, whether a child was subsequently separated from their family, and perpetrator(s) of the maltreatment is important to consider moving forward. Surveying child protective service records for such information, as well as considering variations in culture, parental systems, and child systems, could further clarify individual differences in neurobiological and psychological development (see Barnett, Manly & Cicchetti, 1993, for extensive discussion of these issues; also (Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001).

These limitations not withstanding, our results provide evidence that maltreatment impacts important neurobiological circuitry involved with emotion regulation. Variations at this neurobiological level may convey risk for increases in internalizing symptomatology, particularly in the context of more recent exposure to stress. These results have important implications for the development and implementation of novel resilience-promoting interventions in those that have experienced insensitive, emotionally insecure, or physically harmful parent-child interactions. Additional research is needed to clarify the complex relationships between child maltreatment and related long-term physical and mental difficulties; our data are however an important step in the ability to predict, prevent, and treat maltreatment-related internalizing psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grants R01DA033369 and R01DA031579 to ARH), a Postdoctoral Fellowship provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse through the Center for the Study of Adolescent Risk and Resilience (Grant P30DA023026 to JLH), and a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant T32HD0737625) through the Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to JLH.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- Amaral DG, Price JL. Amygdalo-cortical projections in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984;230:465–496. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, De Olmos J. Projections from the amygdala to basoventral and mediodorsal prefrontal regions in the rhesus monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;300:549–571. doi: 10.1002/cne.903000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Alex; 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: an integrative account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan R, Perlis RH, Fagerness J, Pizzagalli DA. The impact of mineralocorticoid receptor ISO/VAL genotype (rs5522) and stress on reward learning. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2010;9:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke KC, Burke JD, Regier DA, Rae DS. Age at onset of selected mental disorders in five community populations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:511–518. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Jeong B, Polcari A, Rohan ML, Teicher MH. Reduced fractional anisotropy in the visual limbic pathway of young adults witnessing domestic violence in childhood. NeuroImage. 2012;59:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Jeong B, Rohan ML, Polcari AM, Teicher MH. Preliminary evidence for white matter tract abnormalities in young adults exposed to parental verbal abuse. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Gunnar MR. Integrating biological measures into the design and evaluation of preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:737–743. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Tucker D. Development and self-regulatory structures of the mind. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:533–549. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Turpin G. The life events scale for students: validation for use with British samples. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;20:747–751. [Google Scholar]

- Covault J, Tennen H, Armeli S, Conner TS, Herman AI, Cillessen AHN, Kranzler HR. Interactive Effects of the Serotonin Transporter 5-HTTLPR Polymorphism and Stressful Life Events on College Student Drinking and Drug Use. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski U, Stuhrmann A, Beutelmann V, Zwanzger P, Lenzen T, Grotegerd D, et al. Limbic Scars: Long-Term Consequences of Childhood Maltreatment Revealed by Functional and Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation--a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–594. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Whalen PJ. The amygdala: vigilance and emotion. Molecular Psychiatry. 2001;6:13–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito SA, Viding E, Sebastian CL, Kelly PA, Mechelli A, Maris H, McCrory EJ. Reduced orbitofrontal and temporal grey matter in a community sample of maltreated children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eluvathingal TJ, Chugani HT, Behen ME, Juhász C, Muzik O, Maqbool M, et al. Abnormal brain connectivity in children after early severe socioemotional deprivation: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2093–2100. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, Bor W. Stress Sensitization and Adolescent Depressive Severity as a Function of Childhood Adversity: A Link to Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:287–299. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Prater KE, Hoeft F, Menon V, Schatzberg AF. Failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:545–554. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink LA, Bernstein D, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M. Initial reliability and validity of the childhood trauma interview: a new multidimensional measure of childhood interpersonal trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1329–1335. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Barbas H. Pathways for emotion: interactions of prefrontal and anterior temporal pathways in the amygdala of the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 2002;115:1261–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser J-P, van Os J, Portegijs PJM, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding HC, Milliren CE, Austin SB, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA. Child Abuse, Resting Blood Pressure, and Blood Pressure Reactivity to Psychosocial Stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka AX, Hanson JL, Radtke SR, Hariri AR. Reduced hippocampal and medial prefrontal gray matter mediate the association between reported childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety in adulthood and predict sensitivity to future life stress. Biology of Mood & Anxiety Disorders. 2014;4:12. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan RM, Behen ME, Helder E, Makki MI, Chugani HT. Altered Water Diffusivity in Cortical Association Tracts in Children with Early Deprivation Identified with Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20:561–569. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and Depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Henry R, Daley SE. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Chung MK, Avants BB, Shirtcliff EA, Gee JC, Davidson RJ, Pollak SD. Early stress is associated with alterations in the orbitofrontal cortex: a tensor-based morphometry investigation of brain structure and behavioral risk. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:7466–7472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0859-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Nacewicz BM, Sutterer MJ, Cayo AA, Schaefer SM, Rudolph KD, et al. Behavioral problems after early life stress: contributions of the hippocampus and amygdala. Biological Psychiatry. 2015;77:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR. The Neurobiology of Individual Differences in Complex Behavioral Traits. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:225–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Bruce AE, Lumley MN. The role of childhood abuse and neglect in the sensitization to stressful life events in adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:730–741. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herringa RJ, Birn RM, Ruttle PL, Burghy CA, Stodola DE, Davidson RJ, Essex MJ. Childhood maltreatment is associated with altered fear circuitry and increased internalizing symptoms by late adolescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:19119–19124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310766110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herts KL, McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Emotion Dysregulation as a Mechanism Linking Stress Exposure to Adolescent Aggressive Behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1111–1122. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9629-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Gundapuneedi T, Rao U. White matter disruptions in adolescents exposed to childhood maltreatment and vulnerability to psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2693–2701. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshad N, Kochunov PV, Sprooten E, Mandl RC, Nichols TE, Almasy L, et al. Multi-site genetic analysis of diffusion images and voxelwise heritability analysis: a pilot project of the ENIGMA-DTI working group. NeuroImage. 2013;81:455–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitzke BT, Hilt LM, Pollak SD. Maltreated youth display a blunted blood pressure response to an acute interpersonal stressor. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:305–313. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.848774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory EJ, Viding E. The theory of latent vulnerability: Reconceptualizing the link between childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;27:493–505. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:815.e14–830.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Alves S, Mendes WB. Child maltreatment and autonomic nervous system reactivity: identifying dysregulated stress reactivity patterns by using the biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76:538–546. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Fear Extinction as a Model for Translational Neuroscience: Ten Years of Progress. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:129–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe S, Reid M. Gene-environment interactions in depression research. Psychological Science. 2008;19:947. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecraft RJ, Geula C, Mesulam MM. Cytoarchitecture and neural afferents of orbitofrontal cortex in the brain of the monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;323:341–358. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Wakana S, Van Zijl PC, Nagae-Poetscher LM. MRI atlas of human white matter. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES. Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 2003:61–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Pandya DN. Association Fiber Pathways to the Frontal-Cortex From the Superior Temporal Region in the Rhesus-Monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;273:52–66. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino LJ, Crane AM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Direct and indirect pathways from the amygdala to the frontal lobe in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1981;198:121–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Beer JS. Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: convergence of rat and human studies. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. 2012. Open access available at: http://cran.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following adoption after severe global early privation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1998;39:465–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Stein MB, Asmundson GJ, McCreary DR, Forde DR. The childhood trauma questionnaire in a community sample: psychometric properties and normative data. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:843–857. doi: 10.1023/A:1013058625719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapero BG, Black SK, Liu RT, Klugman J, Bender RE, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Stressful Life Events and Depression Symptoms: The Effect of Childhood Emotional Abuse on Stress Reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;70:209–223. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Knodt AR, Radtke SR, Hariri AR. A Neural Biomarker of Psychological Vulnerability to Future Life Stress. Neuron. 2015;85:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Anderson CM, Polcari A. Childhood maltreatment is associated with reduced volume in the hippocampal subfields CA3, dentate gyrus, and subiculum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E563–E572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Hare TA, Millner A, Gilhooly T, Zevin JD, Casey BJ. Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation. Developmental Science. 2011;14:190–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromp DPM, Grupe DW, Oathes DJ, McFarlin DR, Hernandez PJ, Kral TRA. Reduced structural connectivity of a major frontolimbic pathway in generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:925–934. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh WA, Dawson J, Mattingly MJ. How are we measuring resilience following childhood maltreatment? Is the research adequate and consistent? What is the impact on research, practice, and policy? Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2010;11:27–41. doi: 10.1177/1524838009358892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168:706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]