Abstract

Chronological age is used as a marker for age-associated changes in cognitive function. However, there is great interindividual variability in cognitive ability among people of the same age. Physiological age rather than chronological age should be more closely associated with age-related cognitive changes because these changes are not universal and are likely dependent on several factors in addition to the number of years lived. Cognitive function is associated with successful self-management, and a biological marker that reflects physiological age and is associated with cognitive function could be used to identify risk for failure to self-manage. The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between telomere length, a known biomarker of age; blood pressure; cognitive assessments and adherence to antihypertensive medication among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. We administered a battery of cognitive assessments to 42 participants (M = 69 years of age), collected blood samples, and isolated peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes for genomic DNA. We determined relative telomere length using Cawthon’s method for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and measured medication adherence using an electronic medication monitoring system (MEMS by Aardex) over 8 weeks. Findings indicate that telomere length was inversely associated with systolic blood pressure (r = −.38, p < .01) and diastolic blood pressure (r = −.42, p < .01) but not with cognitive assessments or adherence. We discuss the nonsignificant findings between telomere length and cognitive assessments including the potential modifying role of gender.

Keywords: telomere length, biological age, RT-qPCR, cognitive processes, blood pressure, hypertension

Several theorists in aging have advocated identifying a biomarker for physiological age beyond chronological age, and this goal has been the focus of work groups at the National Institute on Aging (NIA) over the past two decades (Butler et al., 2004). Biomarkers are measures that provide information on physiological status (Warner, 2004). In 2000, an NIA work group developed a research agenda that included examining telomere length as a possible biomarker of human aging, indicating that although telomere length is not a direct measure of age, it could show biological age in certain cells. Few investigators have examined the relationship between telomere length and cognition, with the exceptions of Harris (Harris et al., 2006), Martin-Ruiz (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2006) and Valdes (Valdes et al., 2010). Others have developed composites of biological markers that include measures of sensory function, muscle strength, lung and cardiovascular function and then have associated the composite with cognitive assessments in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Anstey, Lord, & Williams, 1997; MacDonald, Dixon, Cohen, & Hazlitt, 2004). The latter approach involves collecting information on biological parameters that may be compromised due to factors other than aging (e.g., visual acuity); therefore the association between these biological markers and cognitive function may be less specific and more prone to error. A more parsimonious approach would identify a biomarker that is associated with cognitive aging and would then have predictive validity for instrumental activities of daily living including medication taking.

Further, a biomarker should reflect the fact that biological aging is genetically, environmentally and stochastically determined (Vina, Borras, & Miquel, 2007; Weinert & Timiras, 2003). The rationale for examining telomere length as a biomarker of aging is based on the cellular theory of aging that focuses on cell senescence. This theory accounts for genetic, environmental and stochastic influences on aging (Njajou et al., 2007; Warner, 2004; Weinert & Timiras, 2003). Cell senescence takes place because there are a limited number of available cell replications and when this number is reached, cell senescence or apoptosis occurs (Hayflick, 1965). In 1971, Olovnikov (1996) suggested that cell division is limited by what we have come to know as telomere length and the activity of telomerase, an enzyme that is necessary for rebuilding telomeres. Telomeres are DNA–protein complexes that cap the chromosome ends, thus promoting chromosome stability. Telomere length is a function of cell divisions; that is, as the number of cell divisions increases (replicative aging) telomere length decreases (Effros, 2009; Epel et al., 2004; von Zglinicki & Martin-Ruiz, 2005). Telomere shortening happens in the absence of telomerase because DNA polymerase does not fully replicate on the 3’ single-stranded overhang (Wright, Tesmer, Huffman, Levene, & Shay, 1997). This phenomenon is referred to as the end replication problem. There is wide interindividual variation in telomere length at birth, implicating a potential genetic basis for the limits of cell replication. Investigators have also demonstrated that environmental factors, including stress, increase cell replication and therefore decrease telomere length (Epel et al., 2004; for a review see Epel, Daubenmier, Moskowitz, Folkman & Blackburn, 2009). Telomere shortening has predictive validity since researchers have found it to be linked to mortality among older adults even when controlling for other factors (Farzaneh-Far et al., 2008; Martin-Ruiz et al., 2006). Telomere length of peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) may be a valid biomarker of age-related cognitive decline as short telomeres in one tissue might act as risk markers (von Zglinicki & Martin-Ruiz, 2005).

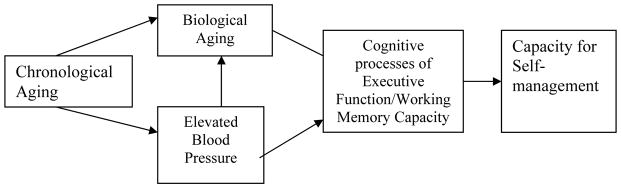

The association between telomere length and cognition should be particularly pronounced among individuals with hypertension because the rate of telomere shortening is accelerated relative to chronological age in this population (Fuster, Diez, & Andres, 2007). Furthermore, cognitive decline is associated with the severity of hypertension (de Leeuw et al., 2002). There is evidence linking hypertension with both cognitive decline and accelerated aging (demonstrated by shortening of telomeres). The purpose of this investigation was to examine the value of telomere length as a biomarker of cognitive aging among individuals with known hypertension. We used the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1 to guide this investigation, where chronological aging influences biological aging and the development of elevated systolic blood pressure (SBP) among middle-aged and older adults. We hypothesized that biological aging is inversely associated with SBP. Biological aging should be associated with age-related performance on measures of working memory and executive function and consequently with medication adherence (Insel, Morrow, Brewer, & Figueredo, 2006; Stilley, Bender, Dunbar-Jacob, Sereika, & Ryan, 2010). Therefore, telomere length may serve as a useful biomarker of cognitive aging among older adults with a diagnosis of hypertension.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model depictin g the potential causal paths and associations among chronological age, biological age (as measured by telomere length), blood pressure among those with hypertension, and the cognitive processes of executive function/working memory capacity with consequent effects on capacity for self-management (as indicated by taking medications as prescribed).

Methods

Sample

We recruited individuals from community centers in a variety of locations and neighborhoods with the intention of obtaining a representative sample of middle-aged and older adults with hypertension. The sample comprised 42 community-dwelling, independently living adults (50 years of age or older). A power analysis indicated that a sample size of 42 was sufficient for a moderate degree of association. All potential participants were currently prescribed at least one antihypertensive agent for hypertension, which was verified by the data collector who read the prescription label. We screened participants for dementia and depression using the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE), with scores < 24 used as an indication of potential dementia (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), and the Short Form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), with scores > 6 indicating possible depression (Fountoulakis et al., 1999). Using this cut-off score with the GDS-15 has a reported sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 95%. The Institutional Review Board of the university approved this study and dAta collection occurred at the University.

Procedure

Following a formal consent procedure and screening for dementia and depression, we obtained two seated BP measures 5 min apart with a digital BP device (Omron HEM 739, Omron Healthcare, Inc., Bannockburn, IL). We then drew blood for genomic DNA analysis, obtained demographic information, and completed the cognitive assessments. If participants were taking more than one antihypertensive agent, we wrote the name of each agent on a slip of paper and randomly chose which antihypertensive agent to monitor. Participants then transferred one of their prescribed antihypertensive medications to a medication container with a Medication Event Monitoring cap (MEMS) (Aardex, 2010). Study personnel picked up the MEMS cap 8 weeks later.

Measures

Demographic variables

We asked participants questions about their age, marital status, and financial well-being (1 = have enough money to do whatever I want, 2 = have enough money, 3 = barely make ends meet, 4 = not able to make ends meet), the number of years of schooling completed and if they were hospitalized during the past year. We also asked them how many years it had been since they were diagnosed with high BP and for how many years they had been receiving treatment for high BP.

Cognitive function

We used six cognitive tests and subtests because they assess different aspects of cognitive functioning. These measures were Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT; Smith, 1973); logical memory (immediate and delayed), letter–number sequence and mental control from the Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition (WMS III; The Psychological Corporation; Wechsler, 1997); the 64-computer version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay, & Curtis, 1993), which we used for categories achieved and perseveration errors; and the STROOP test version from the Stoelting Company ("STROOP Color and Word Test, Adult Version," 2006). The validity and reliability of the measures have been extensively demonstrated (Strauss, Sherman, & Spreen, 2006; Wechsler, 1997).

Blood pressure

We obtained two seated BP readings, 5 min apart, from the nondominant arm extended at the level of the heart, following the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of Blood Pressure guidelines (Chobanian et al., 2003). We calculated mean SBP and DBP by averaging the two seated measures.

Medication adherence

We assessed medication adherence using adherence to the interdose interval for the monitored medication over an 8-week interval, collecting data electronically using the Medication Event Monitoring system developed by Aardex (Aardex, 2010).

Telomere measurement

We used peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes isolated from participants as the source of genomic DNA for telomere length determination. In brief, we isolated PBL from blood samples within 24 hr of collection using standard Histopaque™ density-barrier procedures. We purified DNA using a QIAamp Mini kit (Chatsworth, CA), measured concentration and purity using an Eppendorf Biophotometer (Hamburg, Germany) and assessed DNA integrity by agarose-gel electrophoresis.

To measure the relative length of telomere sequences in each participant’s DNA sample we used Cawthon’s (2002) quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) method employing an Applied Biosystems Model 7300 thermal cycler (Foster City, CA) and the primers and reaction conditions that Cawthon described. We measured telomere sequences and 36B4 sequences in separate PCR plates and assayed all samples in triplicate. In addition, we measured telomere and 36B4 sequences in a standard DNA sample (human Jurkat T-cell line) on each PCR plate to control for interassay variability. We calculated amounts of telomere and 36B4 PCR products for each sample by instrument software using the cycle threshold (Ct) method.

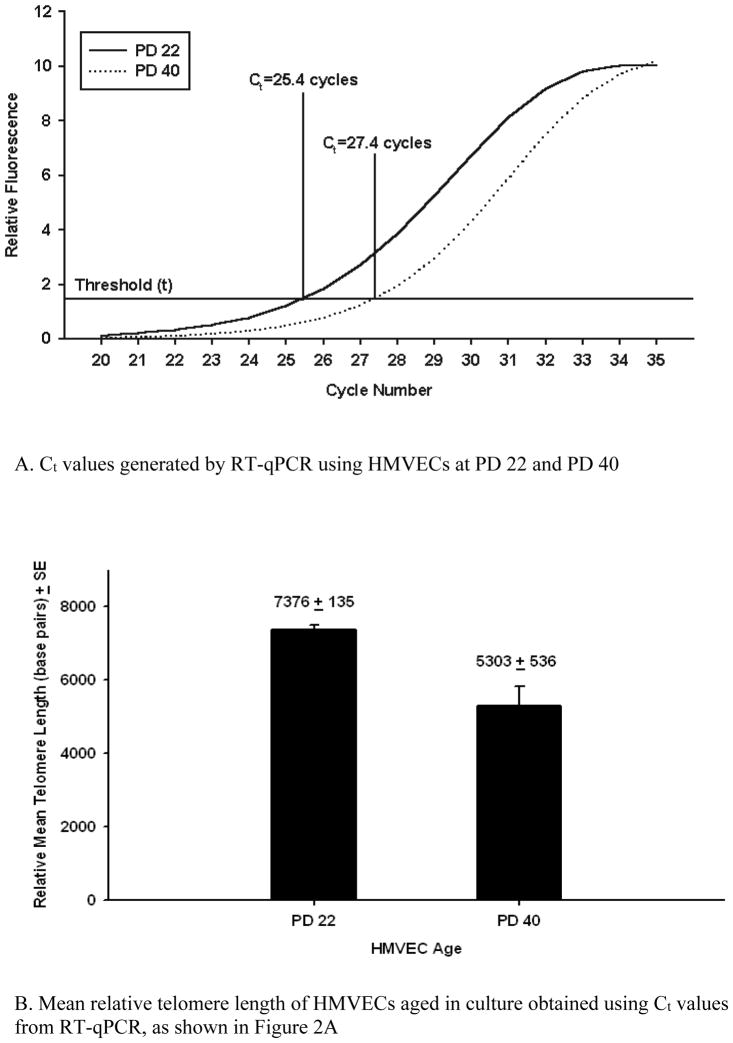

We used DNA samples from human lung microvascular cells (HMVECs) serially subcultured in vitro to verify that the telomere assay was valid to measure telomeres and sensitive to detect telomere shortening under controlled conditions. The HMVECs originated from a 3-year-old female donor and were obtained at population doubling (PD) number 20 (BioWhittaker/Clonectics, Walkersville, MD). We grew the HMVECs in culture and froze aliquots of samples at PD 22 and PD 40. We then compared telomere length in HMVECs at PD 40 to that of HMVECs at PD 22 following DNA isolation and relative telomere length determination as described above. In Figure 2A we show that the telomere cycle threshold (Ct) values for the PD 40 cells is 2 amplification cycles greater than that of the PD22 cells, indicating shorter telomeres. We calculated an estimated telomere length in base pairs for these samples (Figure 2B), using the regression equation Cawthon derived (2002), from a comparison of relative telomere lengths determined by RT-qPCR with telomere lengths in base pairs determined by telomere restriction fragment length analysis. Although only an estimate of actual length, this comparison demonstrates that the RT-qPCR assay can detect differences in telomere length due to differences in HMVECS cell population doublings of cells from the same individual.

Figure 2.

Validation and sensitivity of procedure for telomere length calculation using human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) aged by sequential subculture. Ct = cycle threshold; PD = population doubling; RT-qPCR = quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Demographic Variables

The sample comprised 42 participants with a mean age of 69 years (range = 53–86 years), 79% of whom were women (n = 33), 55% (23) non-Hispanic White, 24% (10) of Hispanic heritage, and 21% (9) African American. All participants were prescribed at least one medication to control high BP. The mean GDS-15 score was 1.98 with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = .57 for the sample screened for depression. Table 1 presents mean, standard error, and range for demographic and health-related variables.

Table 1.

Mean, Standard Error, and Range of Demographic and other Variables

| Mean (SE) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 69.33 (1.25) | 53 – 86 |

| Education in years | 14.50 (0.59) | 8 – 24 |

| Financial well being | 2.00 (0.14) | 1 – 4 |

| Mean SBP mmHg | 133.48 (3.15) | 95 – 182 |

| Mean DBP mmHg | 75.60 (1.6) | 57 – 103 |

| Length of time with hypertension diagnosis (in years) | 14.64 (1.68) | 1 – 40 |

| Number of antihypertensive medications | 1.62 (0.13) | 1 – 4 |

| MMSE | 28.17 (0.27) | 24 – 30 |

| % of doses taken on schedule | 74.7% (3.8) | 0 – 100% |

Cognitive Measures

We present the mean, standard error, and range of scores in Table 2 for SDMT; WMS-III Logical Memory (immediate and long-delay total recall, immediate and long-delay thematic recall, recognition memory), Letter–Number Sequence and Mental Control; WCST categories completed and perseveration errors; and the STROOP interference test.

Table 2.

Mean, Standard Error, and Range of Cognitive Variables

| Mean (SE) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test | 37.95 (1.8) | 7 – 58 |

| WMS immediate total recall | 17.12 (1.25) | 4 – 33 |

| WMS long delay total recall | 15.88 (1.28) | 3 – 34 |

| WMS immediate thematic | 15.52 (0.62) | 7 – 23 |

| WMS long delay thematic | 9.98 (0.42) | 5 – 15 |

| WMS recognition | 23.00 (0.62) | 15 – 30 |

| Letter-Number Sequence | 7.07 (0.46) | 2 – 13 |

| Mental Control | 19.74 (0.69) | 12 – 30 |

| WCST categories completed | 2.02 (0.24) | 0 – 5 |

| WCST perseveration errors | 16.33 (1.8) | 4 – 46 |

| STROOP interference | −6.60 (1.33) | −28 – 20 |

Associations Between Indicators of Severity of Hypertension and Telomere Length

Neither the number of years since diagnosis of hypertension nor the number of years receiving treatment for hypertension correlated with telomere length (r = −.04, and r = −.06, respectively). Telomere length was associated with both mean SBP (r = −.38, p < .01) and mean DBP (r = −.42, p < .01; Table 3). Higher BP was associated with shorter telomeres.

Table 3.

Zero Order Correlations of telomere length, blood pressure and the cognitive measures

| Variables | Telo | SBP | DBP | SDMT | LMI | LMLD | L-N | Men C | PE WCST | CC WCST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | −.38** | |||||||||

| DBP | −.42** | .63** | ||||||||

| SDMT | −.27* | −.09 | .08 | |||||||

| LMI | −.07 | −.42** | −.16 | .60** | ||||||

| LMLD | −.08 | −.47** | −.23 | .60** | .91** | |||||

| L-N | −.11 | −.17 | .04 | .74** | .56** | .58** | ||||

| Men C | −.16 | −.18 | .01 | .79** | .66** | .61** | .79** | |||

| PE WCST | −.16 | .24 | .24 | −.45** | −.47** | −.45** | −.42** | −.44** | ||

| CC WCST | .01 | −.38** | −.14 | .68** | .69** | .70** | .65** | .63** | −.71** | |

| STROOP | −.25 | −.00 | .02 | .10 | .23 | .24 | .17 | .13 | −.19 | .12 |

Note. Telo = Mean Telomere Length; MSBP = Mean Systolic Blood Pressure; MDBP = Mean Diastolic Blood Pressure; SDMT = SDMT correct responses; LMI = Logical Memory Immediate; LMLD = Logical Memory Long Delay; L-N = Letter-Number Sequence; Men C = Mental Control; PE WCST = Perseveration Errors WCST; CC WCST = Categories Completed WCST; STROOP = STROOP Interference score.

p < .05,

p < .01

Associations Among Telomere Length, Demographic Variables, Cognitive Processes and Adherence

We present correlations between telomere length and SDMT; WMS-III Logical Memory immediate and long delay, Letter–Number Sequence, Mental Control; perseveration errors and categories completed on the WCST; and the STROOP interference score in Table 3. Telomere length was significantly associated with SDMT in an unexpected direction (longer telomere length was associated with fewer correct responses on the SDMT).

Chronological age was positively associated with telomere length (r = .20) and inversely associated with mean DBP (r = −.45, p < .01), indicating that older persons had lower DBP. Chronological age was also associated with taking more medications (r = .29, p < .05) and more antihypertensive agents (r = .42, p < .01).

As expected, chronological age was inversely associated with performance on the MMSE (r = −.36, p < .01), Mental Control (r = −.30, p <.05), Letter–Number Sequence (r = −.34, p < .05), SDMT (r = −.43, p < .01) and number of categories completed on the WCST (r = −.33, p < .05). In general, as expected chronological age was inversely associated with performance on cognitive assessments.

We examined the association between gender and telomere length and found it to be r = −.25, with a p-value = .058. After controlling for chronological age, we still found a similar association between gender and telomere length (β= −.26). While the current sample demonstrates a nonsignificant relationship between gender and telomere length, the association approaches significance and is intriguing given the small numbers of males in the sample (n = 9). Therefore, we conducted a subsample analysis examining the associations of MMSE and telomere length for women and men. Among the women the MMSE was inversely associated with telomere length (r = −.32, p < .05), whereas we would have expected a positive association between cognitive function and telomere length. Conversely, while not significant likely due to the small number of men, the association between MMSE and telomere length in men was in the expected direction (r = .36). In this sample, ethnicity was not associated with significant differences in telomere length.

Telomere length was not associated with medication adherence (r = .17); however adherence was associated with cognitive measures in this sample. If telomere length were associated with the cognitive measures, it would be anticipated that telomere length would also be associated with functional abilities, particularly adherence to prescribed medication.

Discussion

In this study, we found that leukocyte telomere length was inversely associated with mean SBP and mean DBP among middle-aged and older adults as predicted in the model. Importantly, while mean SBP and DBP were associated with telomere length, the cognitive assessments were not. Within this sample, it appears gender may have a modifying role in the association between telomere length and cognitive function and/or medication adherence. Given these findings, telomere length of peripheral blood leukocytes may reflect the effects of hypertension, but it does not reflect function of the central nervous system with respect to cognitive aging.

Telomere Length and Vascular Disease

The results linking higher SBP and DBP with shortened telomeres converge with other studies that indicate hypertension is associated with telomere shortening (Nakashima et al., 2004) and to the development of atherosclerotic plaques in those with hypertension (Benetos et al., 2004). Association, of course, is not causation, and discussion continues regarding telomere shortening as a cause or consequence of age-related diseases (for reviews see Edo & Andres, 2005; Fuster & Andres, 2006; Minamino & Komuro, 2008). The pathological processes involved in hypertension implicate primary and secondary activation of the immune system. We used leukocytes in this study to obtain information on telomere length. Calculating telomere length using leukocytes could have consequences for the resulting associations with other factors because hypertension involves inflammation. Telomere length, based on cell replications of leukocytes is likely a good biomarker for severity of hypertension.

Consistently, investigators have considered leukocyte telomere length to be a measure of somatic fitness since studies have demonstrated a link between telomere length and diseases of aging (for a review see Aviv, 2006). However, self-reported length of time since the diagnosis of hypertension and length of time since start of treatment with antihypertensives were not associated with telomere shortening. This finding suggests that length of time with hypertension is not the critical factor. Rather, the severity of the hypertension is likely linked to telomere length. The finding that telomere length is not associated with the length of time with hypertension could also reflect known problems with the validity of self-report (for more information on self-report see Schwarz & Oyserman, 2001). When we asked participants to provide information regarding when the diagnosis of hypertension was made, they were often vague with estimates and seemed to base these estimates on their recall of when they began treatment. The longer the time since the initiation of treatment, the less likely self-report may reflect actual years undergoing treatment because people have difficulty recalling events that occur years ago.

BP is an indirect measure of aging that is often included in composites of biological aging and then correlated with cognitive aging. Investigators have found associations between hypertension and cognitive decline in several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Kilander, Nyman, Boberg, Hansson, & Lithell, 1998; Leys & Pasquier, 1999). When BP is included in composites of biological aging, it is not surprising that the composite is associated with cognitive decline. Biological age, then, must be understood within the context of vascular aging, and including BP measures in composites may point to a causal association between vascular health and brain health. We did find associations between BP and some of the cognitive measures.

Telomere Length and Cognition

Contrary to what we proposed in the model, in this study involving a hypertensive sample leukocyte telomere length was not a useful biomarker of cognitive aging. Leukocyte telomere length was not associated with cognitive measures except in one instance where the SDMT score was associated with telomere length in an unexpected direction. This association could reflect type 1 error since this single association without other measures following a similar pattern is difficult to interpret. Additionally, the small sample size may affect the stability of the correlations, although finding no or inconsistent associations between telomere length and cognitive assessments converges with other findings. Harris and her colleagues (2006) examined the association between telomere length and cognitive assessments among a cohort of individuals born in 1921 (all subjects were 79 years of age). They found a weak association between telomere length and verbal fluency (r = −.16) and no association between telomere length and other cognitive measures. These findings suggest that the lack of association between telomere length and cognitive function may reflect an older cohort. Zekry and colleagues (2010) reported no differences in telomere length when comparing cognitively normal persons with those diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or dementia among the oldest old, suggesting again that telomere length is not associated with impaired cognition in this age group. Conversely, Valdes and colleagues (2010) found an association between a subset of cognitive measures from the Cantab (Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery); that is, Delayed Matching to Sample and Space Span Test, each nonverbal measures (Robbins, James, Owen, & Sahakian, 1994) and leukocyte telomere length among healthy women with a mean age of 48.6 years. Focusing on twins with discordant telomere length, investigators chose 40 fraternal twin pairs (average midquartile age range between 42.8 and 60.1 years) and compared their relative performance on the cognitive measures. Working memory assessments were significantly associated with telomere length in a positive direction. In support of the Valdes study, which involved women only, investigators have also found evidence that telomere length differs between genders (Cawthon, Smith, O’Brien, Sivatchenko, & Kerber, 2003; Mayer et al., 2006), particularly when considering measures of vascular health in men and women across the adult lifespan (Benetos et al., 2001). Therefore, age cohort and gender are likely involved in the differences among the few studies that have examined telomere length as a biomarker for cognitive aging. Further study is warranted, and telomere length may yet prove to be a valuable marker of age-associated cognitive decline.

The determination of biomarkers associated with cognitive aging and, importantly, biomarkers that link to theories of aging may be useful for identifying causal factors and consequent interventions to prevent cognitive decline. While a potential causal factor, cell senescence may not be critical in the study of brain age. As Harris and colleagues (2006) suggested, there are few studies about the influence of telomere length in nonmitotic human brain cells. Using rats, Cherif, Tarry, Ozanne, and Hales (2003) found evidence for gender- and organ-specific telomere shortening, but specifically found little or no telomere shortening in brain tissue. It would appear that leukocyte telomere length may not be a robust indicator of age-related cognitive decline.

On the other hand, it may be that as we learn more about telomere biology, we may reach a better understanding of the relationship between telomere shortening and cognition. Studies (Cheng et al., 2007) have revealed that cellular mechanisms for neuronal protection from telomere shortening are more complex than merely a balance between telomere length reduction and cell divisions and telomerase. Newly discovered proteins also operate to protect mature neurons and make them highly resistant to telomere damage. These mechanisms may have a role in neuronal longevity and implications for interventions to prevent cognitive decline. Therefore, again, telomere length from peripheral blood leukocytes may not be the best measure for examining the association between telomere shortening and cognition.

Limitations

This study involved 42 middle-aged and older adults with known hypertension. Recent reviews of telomere length and age-associated changes suggest that the large interindividual differences in telomere length at birth, the large interindividual differences across the lifespan in telomere attrition, and the limitations to current methods used to measure telomere length necessitate large sample sizes to investigate age-associated changes and telomere length (Aviv, 2008). Our sample size, although large enough to detect a moderate effect size in behavioral studies, was not sufficient to detect an association in studies using q-PCR for calculations of telomere length for reasons indicated by Aviv.

In the present study, chronological age was not significantly associated with telomere length, and the direction of the relationship differed depending on gender. Age and gender have specific modifying influences on the association between telomere length and age-related factors (Cherif et al., 2003; Guan et al., 2007). In other investigations, telomere length was associated with chronological age in men (Benetos et al., 2001; Cawthon et al., 2003), but in this sample although not a statistically significant finding, women had shorter telomeres, and even after controlling for chronological age, gender was not significantly associated with telomere length. Examining telomere length in individuals pre- and post-50 years of age, Guan and colleagues (2007) found that the difference in telomere length between men and women was greatest among 40 and 50 year olds, whereas the rate of telomere attrition increased in women after age 50 relative to men. In support of the role estrogen may have regarding telomere length, using a case–control design, Lee, Im, Kim, Lee, and Shim (2005) found longer telomere length for postmenopausal women on long-term hormone replacement compared to women not taking hormone replacement even after controlling for several potential confounding variables. Estrogen may provide protection against telomere shortening, but in the present study we did not examine either menopausal status or use of hormone-replacement therapy. Investigators in future studies need to consider menopausal status in addition to the possible influence of hormone-replacement therapy on telomere attrition. Our findings suggest that further investigation of gender differences in telomere length and the association of telomere length with other age-related factors in specific clinical populations is needed.

Implications for Future Research

Future research should examine other biomarkers of aging and cognitive function. Cognitive function has important implications for self-management and consequently affects ongoing success of independent living (Insel et al., 2006; Stilley et al., 2010). Findings from these types of investigations could help to identify risk and lead to potential interventions. Part two of this article, “Biomarkers of Cognitive Aging,” offers a potential avenue for further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, R03 NR010010-01 and P20 NR007794.

Contributor Information

Kathleen C. Insel, Email: insel@email.arizona.edu, Associate Professor, University of Arizona, College of Nursing, P.O. Box 210203, Tucson, Arizona, 85721-0203 520 626 6220.

Carrie J. Merkle, Email: cmerkle@nursing.arizona.edu, Associate Professor, University of Arizona, College of Nursing.

Chao-Pin Hsiao, Email: hsiaoc@mail.nih.gov, Postdoctoral Fellow, Intramural Program, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health.

Amy N. Vidrine, Email: avidrine@nursing.arizona.edu, Research Specialist, University of Arizona, College of Nursing.

David W. Montgomery, Email: David.Montgomery2@va.gov, Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Arizona.

References

- Aardex C. Advanced Analytic Research on Drug Exposure. 2010 Retrieved 7/12/10, 2010, from ttp:// www.aardexgroup.com/aardex_index.php?group=aardex&id=85.

- Anstey KJ, Lord SR, Williams P. Strength in the lower limbs, visual contrast sensitivity, and simple reaction time predict cognition in older women. Psychology & Aging. 1997;12(1):137–144. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv A. Telomeres and human somatic fitness. Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2006;61(8):871–873. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv A. The epidemiology of human telomeres: faults and promises. Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2008;63(9):979–983. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetos A, Gardner JP, Zureik M, Labat C, Xiaobin L, Adamopoulos C, et al. Short telomeres are associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43(2):182–185. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113081.42868.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetos A, Okuda K, Lajemi M, Kimura M, Thomas F, Skurnick J, et al. Telomere length as an indicator of biological aging: the gender effect and relation with pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity. Hypertension. 2001;37(2 Part 2):381–385. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RN, Sprott R, Warner H, Bland J, Feuers R, Forster M, et al. Biomarkers of aging: from primitive organisms to humans. Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2004;59(6) doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.6.b560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O’Brien E, Sivatchenko A, Kerber RA. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older.[see comment] Lancet. 2003;361(9355):393–395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Shin-ya K, Wan R, Tang SC, Miura T, Tang H, et al. Telomere protection mechanisms change during neurogenesis and neuronal maturation: newly generated neurons are hypersensitive to telomere and DNA damage. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(14):3722–3733. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0590-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherif H, Tarry JL, Ozanne SE, Hales CN. Ageing and telomeres: a study into organ- and gender-specific telomere shortening. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31(5):1576–1583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.[see comment] Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC, Hofman A, van Gijn J, et al. Hypertension and cerebral white matter lesions in a prospective cohort study. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 4):765–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edo MD, Andres V. Aging, telomeres, and atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular Research. 2005;66(2):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(49):17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel E, Daubenmier J, Moskowitz JT, Folkman S, Blackburn E. Can Meditation Slow Rate of Cellular Aging? Cognitive Stress, Mindfulness, and Telomeres. Annuals New York Academy of Science. 2009;1172:34–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzaneh-Far R, Cawthon RM, Na B, Browner WS, Schiller NB, Whooley MA. Prognostic value of leukocyte telomere length in patients with stable coronary artery disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis & Vascular Biology. 2008;28(7):1379–1384. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis KN, Tsolaki M, Iacovides A, Yesavage J, O’Hara R, Kazis A, et al. The validation of the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece. Aging Clinical & Experimental Research. 1999;11(6):367–372. doi: 10.1007/BF03339814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JJ, Andres V. Telomere biology and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research. 2006;99(11):1167–1180. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251281.00845.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JJ, Diez J, Andres V. Telomere dysfunction in hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(11):2185–2192. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef6196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DA, Berg EA. A behavioral analysis of degree of impairment and ease of shifting to new resonses in a Weigl-type cared sorting problem. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1948;39:404–411. doi: 10.1037/h0059831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JZ, Maeda T, Sugano M, Oyama J, Higuchi Y, Makino N. Change in the telomere length distribution with age in the Japanese population. Molecular & Cellular Biochemistry. 2007;304(1–2):353–360. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SE, Deary IJ, MacIntyre A, Lamb KJ, Radhakrishnan K, Starr JM, et al. The association between telomere length, physical health, cognitive ageing, and mortality in non-demented older people. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;406(3):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Experimental Cell Research. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel K, Morrow D, Brewer B, Figueredo A. Executive function, working memory, and medication adherence among older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2006;61(2):102–107. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.p102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilander L, Nyman H, Boberg M, Hansson L, Lithell H. Hypertension is related to cognitive impairment: a 20-year follow-up of 999 men. Hypertension. 1998;31(3):780–786. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Im JA, Kim JH, Lee HR, Shim JY. Effect of long-term therapy on telomere length in postmenopausal women. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2005;46(4):471–479. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leys D, Pasquier F. Arterial hypertension and cognitive decline. Revue Neurologique. 1999;155(9):743–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald SW, Dixon RA, Cohen AL, Hazlitt JE. Biological age and 12-year cognitive change in older adults: findings from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Gerontology. 2004;50(2):64–81. doi: 10.1159/000075557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Ruiz C, Dickinson HO, Keys B, Rowan E, Kenny RA, Von Zglinicki T. Telomere length predicts poststroke mortality, dementia, and cognitive decline. Annals of Neurology. 2006;60(2):174–180. doi: 10.1002/ana.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S, Bruderlein S, Perner S, Waibel I, Holdenried A, Ciloglu N, et al. Sex-specific telomere length profiles and age-dependent erosion dynamics of individual chromosome arms in humans. Cytogenetic & Genome Research. 2006;112(3–4):194–201. doi: 10.1159/000089870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamino T, Komuro I. Role of telomeres in vascular senescence. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13:2971–2979. doi: 10.2741/2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima H, Ozono R, Suyama C, Sueda T, Kambe M, Oshima T. Telomere attrition in white blood cell correlating with cardiovascular damage. Hypertension Research Clinical & Experimental. 2004;27(5):319–325. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njajou OT, Cawthon RM, Damcott CM, Wu SH, Ott S, Garant MJ, et al. Telomere length is paternally inherited and is associated with parental lifespan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(29):12135–12139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702703104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olovnikov AM. Telomeres, telomerase, and aging: origin of the theory. Experimental Gerontology. 1996;31(4):443–448. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(96)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, James M, Owen AM, Sahakian BJ. Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): A factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteers. Dementia. 1994;5(5):266–281. doi: 10.1159/000106735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Oyserman D. Asking Questions About Behavior: Cogntiion, Communication, and Questionnaire Construction. American Journal of Evaluation. 2001;22(2):127–160. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Stilley CS, Bender CM, Dunbar-Jacob J, Sereika S, Ryan CM. The impact of cognitive function on medication management: three studies. Health Psychology. 2010;29(1):50–55. doi: 10.1037/a0016940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests Administration, Norms, and Commentary. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- STROOP Color and Word Test Adult Version. Vol. 2006. Stoelting Co; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tulsky k, Zhu J. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Third Edition, WAIS III (Technical Manual) San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes AM, Deary IJ, Gardner J, Kimura M, Lu X, Spector TD, Aviv A, Cherkas LF. Leukocyte telomere length is associated with cognitive performance in healthy women. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31:986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vina J, Borras C, Miquel J. Theories of ageing. IUBMB Life. 2007;59(4–5):249–254. doi: 10.1080/15216540601178067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zglinicki T, Martin-Ruiz CM. Telomeres as biomarkers for ageing and age-related diseases. Current Molecular Medicine. 2005;5(2):197–203. doi: 10.2174/1566524053586545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner HR. Current status of efforts to measure and modulate the biological rate of aging. Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2004;59(7):692–696. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.7.b692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert BT, Timiras PS. Invited review: Theories of aging. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;95(4):1706–1716. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00288.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WE, Tesmer VM, Huffman KE, Levene SD, WSJ Normal human chromosomes have long G-rich telomereic overhangs at one end. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2801–2809. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zekry D, Herrmann FR, Irminger-Finger I, Ortolan L, Genet C, Vitale A-M, Michel P-P, Gold G, Krause KH. Telomere length is not predictive of dementia or MCI conversion in the oldest old. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31:719–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]