Abstract

We present a comprehensive workflow for large scale (>1000 transitions/run) label-free LC-MRM proteome assays. Innovations include automated MRM transition selection, intelligent retention time scheduling (xMRM) that improves Signal/Noise by >2-fold, and automatic peak modeling. Improvements to data analysis include a novel Q/C metric, Normalized Group Area Ratio (NGAR), MLR normalization, weighted regression analysis, and data dissemination through the Yale Protein Expression Database. As a proof of principle we developed a robust 90 minute LC-MRM assay for Mouse/Rat Post-Synaptic Density (PSD) fractions which resulted in the routine quantification of 337 peptides from 112 proteins based on 15 observations per protein. Parallel analyses with stable isotope dilution peptide standards (SIS), demonstrate very high correlation in retention time (1.0) and protein fold change (0.94) between the label-free and SIS analyses. Overall, our first method achieved a technical CV of 11.4% with >97.5% of the 1697 transitions being quantified without user intervention, resulting in a highly efficient, robust, and single injection LC-MRM assay.

Keywords: Targeted proteomics, multiple reaction monitoring, proteomics database, postsynaptic density

1 Introduction

For ~15 years, large scale proteomic discovery has relied on massive LC-MS/MS analyses to profile proteins in complex biological extracts [1]. Problems with this approach are limited dynamic range, poor run-to-run protein identification reproducibility, and the wide range in the number of peptides isolated from each identified protein [2]. Discovery proteomics also results in MS/MS sequencing of many more peptides (>3) from abundant proteins than needed to identify the parent protein and in resequencing many of the same peptides in each new experiment. For example, since only 6.1% of the ~60 million peptide sequences in the Yale Protein Expression Database (YPED) [3, 4] are unique sequences, almost 94% of our MS instrument time is de facto devoted to resequencing the same peptides. In addition, “discovery” analysis of tryptic and other digests of complex biological extracts usually requires prior separation [e.g., strong cation exchange, isoelectric focusing, etc. [5]] that results in numerous LC-MS/MS runs that require tens of hours of MS instrument time to identify 2,859 – 10,006 proteins in human cell lines [5-7] or the 18,097 proteins in Proteomics DB that have been detected in human tissues, fluids, and cell lines [8, 9].

To address these issues, targeted mass spectrometry approaches such as multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [10] are increasingly being used for quantitation of selected peptides as surrogates for protein expression levels in a wide range of biological and clinical samples [11]. The high-throughput MRM method has a wide linear dynamic range of up to five orders of magnitude, very high precision, and is sufficiently sensitive to detect ng/ml amounts of analytes in biological fluids and cell or tissue protein extracts [12-14]. To date, more than 170,000 MRM assays already have been designed and validated for human, mouse and yeast proteins [15], and in recognition of the important role that approaches like MRM can play in hypothesis-driven research and its increasing impact on clinical proteomics, Targeted Proteomics was selected as the 2012 Nature Method of the Year [16]. As a result of improved instrumentation and software, increasing numbers of larger scale scheduled LC-MRM assays have enabled interrogation of the expression levels of up to about 150 proteins [15, 17-22]. However, as the size of these proteome assays increases so too do the attendant challenges that arise from trying to design and implement MRM assays that monitor ever larger numbers of transitions within the same LC-MRM run times of perhaps 60-90 min [23]. While the tedious aspect of manually designing, implementing, and processing MRM assays involving thousands of transitions has spurred the development of assay methods and software tools to further automate this process [24], challenges remain. In the current study we have designed a label-free targeted proteomics workflow that can develop relative quantitative MRM assays for more than 100 proteins in a single injection without the need for stable isotope dilution standards. To achieve these results we made improvements to several critically important aspects of the workflow that should help pave the way for developing even larger scale assays. Improvements have been made with regard to use of “matched” discovery and triple quad MS platforms, automated MRM transition selection, retention time scheduling, extended MRM data collection, peak integration, data quality assessment, differential expression analysis, and data dissemination through the Yale Protein Expression Database. As an initial test of the MRM proteome assay pipeline, we developed a 90 min LC-MRM assay that relatively or absolutely quantifies 112 targeted proteins by quantifying 5 MS/MS transitions from each of 3 peptides/protein for rat post-synaptic density (PSD) from brain cortex. This assay, which represents one of the largest and most stringent single injection LC-MRM assays, should benefit a wide variety of neurobiological studies that interrogate the molecular basis of altered synaptic transmission.

2 Materials and Methods

Additional Materials and Methods sections describing Rat Brain Post Synaptic Density Preparations, Tryptic Digestion and Sample Clean-up, LC-MS/MS Protein Identification Database Searching, Synthetic Peptides, and Calculation of Normalized Group Area Ratios (NGAR) are in Supporting Information.

2.1 YPED Spectral Library and MRM Peak Selection

Discovery protein identification data obtained from a 5600 TripleTOF interfaced with a Waters nanoACQUITY UPLC® system was initially filtered at 1% FDR (decoy using reversed protein sequences) and then further filtered to include peptides with MASCOT scores greater than or equal to the identity score. The identity score is calculated as: -10*(log(p/#matches)) where p is the probability threshold and #matches is the number of precursor matches. All peptides containing methionine residues were excluded. For each protein, the MS/MS spectra with the highest MASCOT scores were chosen and all y- and b-ions were matched to an in-silico fragmentation and then sorted by peak height intensity. From there the list was filtered so that each protein had three or more peptides and each peptide was distinct within a combined Rodentia Taxonomy SwissProt database blast search [25]. The peptides were then rank ordered based on their number of occurrences in the YPED database. The peptides that occurred most frequently in YPED were then chosen for downstream MRM analysis. After peptide selection, 4-5 MRM transition ions were selected using b- or y-ions and <1250 m/z and having the highest ion intensities. These MRM transitions along with their retention times were exported as a tab-delimited file (tsv) and then used to generate 5500 QTRAP mass spectrometer scheduled MRM method files.

In total we included 24,900 transitions from 5029 peptides encompassing 895 proteins. The 24,900 transitions were initially broken down into 25 scheduled methods with ~1000 transitions per method as outlined in Supporting Table 2, Assay Development, Step 1. Each method was run on the 5500 QTRAP and the resulting data was initially integrated with MultiQuant 2.1 using the MQ4 algorithm followed by manual integration. Data was exported and combined into YPED, where it was filtered such that all 5 transitions for each peptide had a MultiQuant quality score >0.75 and signal to noise >10. The peak areas for the ions from each peptide were then summed for each of the 895 proteins. After rank ordering, the most abundant 148 proteins were chosen for further analyses and the peptides with the top three summed peak areas were then selected for each protein. Using this list we generated three scheduled LC-MRM methods (Supporting Table 2, Assay Development, Step 2). In total we chose 148 proteins from 4280 transitions from 444 peptides. These were broken down into method 1 (1442 Transitions/286 PSD peptides/51 Proteins), method 2 (1427 Transitions/283 PSD Peptides/57 Proteins) and method 3 (1447 Transitions/287 PSD Peptides/40 Proteins). The entire PSD spectral library (blib format) has been uploaded into the Repository of the Yale Protein Expression Database and can be freely downloaded from: http://yped.med.yale.edu/repository/ViewSeriesMenu.do?series_id=4360&series_name=Colangelo_PSD_MRM_Manuscript The final 112 proteins in the PSD assay were then chosen based on relative protein abundance and their relative frequency of identification as PSD proteins in previous studies [26-31].

2.2 Scheduled Multiple Reaction Monitoring

Scheduled LC-MRM was carried out on a 5500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer interfaced with a Waters nanoACQUITY UPLC® system running AB Sciex Analyst® 1.5 software (research version). An MRM scan was carried out by loading 1 μg (5 μl of 0.2 μg/μl) of sample onto a 180 μm × 20 mm 5 μm Symmetry C18 trapping column with 2% ACN/0.1% FA at 15 μl per min for 3 min. After trapping, a 2-40% 60 min linear ACN/0.1% FA gradient was run at a flow rate of 500 nl/min with a 75 μm × 150 mm 1.7 μm BEH130 C18 column. The resulting LC-sMRM data was processed and quantitated using AB Sciex MultiQuant™ 2.1 software and the MQ4 algorithm.

2.3 Extended Multiple Reaction Monitoring Method (xMRM)

For label-free samples, 1 μg (5 μl of 0.2 μg/μl) of digested peptides were injected. For SIS “gold-standard” samples, the SIS peptide mixture was added to resuspended digests for a final concentration of 100 fmol/μl and 0.2 μg/μl PSD digest. Liquid chromatography was identical to sMRM. For extended MRM (xMRM) data collection, label-free samples used an xMRM method containing 1697 transitions with peak windows of 6 min and a cycle time of 2.5 sec. To trigger acquisition of additional transitions we used a threshold of 200 counts which was 4-fold above the highest observed noise level of about 50 counts. We note that the xMRM approach can be used on AB Sciex triple quad (e.g. 5500, 6500) and triple quad/Q-TRAP (e.g. 5500 QTRAP, 6500 QTRAP) instruments. “Gold-standard” SIS spiked samples used an xMRM assay with 1371 transitions with peak windows of 5 min and a cycle time of 2.5 sec. The resulting LC-xMRM data was processed and quantitated using MultiQuant™ 2.1 software (research version). The SF2 algorithm (research version) was used to integrate and score peak groups. Data from MultiQuant were exported and uploaded into YPED [3, 4].The data was also processed via MultiQuant 2.1 MQ4 and Skyline (1.4) using default parameters for each. The Skyline data results have been uploaded to Panorama at https://www.panoramaweb.org/labkey/project/Yale%20Keck/PSD%20MRM/begin.view

2.4 Biostatistics and Fold-Change analysis

We developed an R package entitled MRMandSWATHgraphics, which performs data quality assessment and creates associated graphical plots from either MultiQuant or AB Sciex Peakview™ result tables. We also created a MATLAB package entitled Protein Quant Data Analysis that provides normalization and fold-change analysis. The software includes standard normalization techniques, such as quantile and total-area sum normalization (TAS), and also includes a new algorithm called Most-Likely Ratio Normalization (MLR) [32]. The fold-change calculation was based on a weighted fold-change analysis [33] with modifications for label-free analysis. All of the raw data collected on the integrated transition peak areas were used as input for the fold-change determinations. Following MLR normalization the protein level fold changes were calculated as follows: (i) For each set of biological replicates, a table of weighted average areas was determined using the transition reproducibility values determined during normalization—‘weighted area response’. (ii) Weighted analysis of variance was used to determine the likelihood of difference between the experimental test conditions. The output was in essence a P value as if a t-test had been performed between the different experiments, but the use of weighted values better accounts for poor-quality values in the data being processed. (iii) The “signal-quality” values and the analysis of variance values (from step ii) were used to determine the peptide fold-change values via a weighted-average fold-change calculation. (iv) A peptide signal-quality table was determined from the transition signal-quality table by calculating the median signal quality for each set of transitions. (v) The peptide variance was then determined by calculating the summed weighted average for the transition analysis of variance using the signal-quality table as the weighting factor for the individual transitions. (vi) A protein fold-change value was determined as previously described except that the protein value was again a weighted average using both the peptide signal quality (step iv) and the peptide variance (step v) values as weights. The output was a fold change up or down for each protein and a confidence value as determined from the peptide variance and the peptide signal-quality values. All calculations were carried out in Matlab by executing custom-coded algorithms and data exported either in figure format or as text as previously described. R scripts were then used to generate fold change graphics such as bar charts and scatter plots. All R scripts used in the manuscript are attached as a zip file (“Colangelo_2013_ManuscriptRscript.zip”).

2.5 Data Archival in YPED Repository

All datasets have been loaded into a project folder on the YPED repository entitled “Colangelo_PSD_MRM_Manuscript” (http://yped.med.yale.edu/repository/ViewSeriesMenu.do?series_id=4360&series_name=Colangelo_PSD_MRM_Manuscript). This enables web-accessible retrieval and integrated analysis of three 5600 TripleTOF discovery runs, three 5500 QTRAP datasets for assay development, one 5500 QTRAP dataset for label-free PSD samples 1-6, and three 5500 QTRAP “gold-standard” SIS spiked datasets used for validation of the PSD assay. In addition, each sample contains a resources folder with zipped files containing all raw data, MASCOT peak (mgf files), MASCOT search results (dat files), MRM methods and MultiQuant peak integration results, MRMandSWATHgraphics results, and the MATLAB fold-change analysis result tables.

In addition, all raw data, MRM methods, and MultiQuant results have been uploaded to PeptideAtlas with identifier PASS00554 (http://www.peptideatlas.org/PASS/PASS00554), Username: PASS00554, and Password: IN5394d.

3 Results

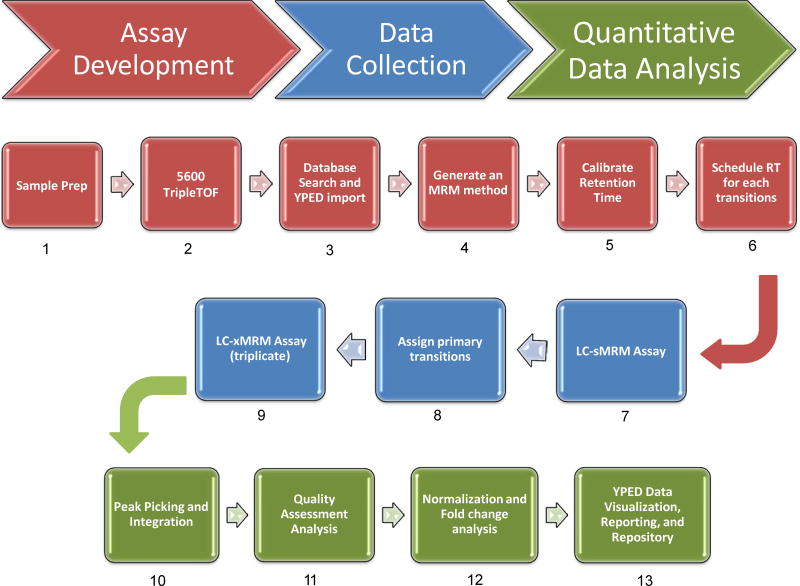

As depicted in Figure 1, the workflow begins by LC-MS/MS “sequencing” as many peptides as possible from a sample type of interest on an AB Sciex 5600 TripleTOF® mass spectrometer. Peptides from the identified proteins are then used as candidates for generating MRM transitions. To develop assays of this size (i.e., 1697 transitions) we made several improvements to scheduled MRM that are described below.

Figure 1.

MRM Proteome Assay workflow which utilized a 5600 TripleTOF Mass Spectrometer, Yale Protein Expression Database (YPED), and a 5500 QTRAP mass spectrometer to identify the best peptides and corresponding MS/MS transitions to rapidly develop a targeted proteomic assay (Steps 1-6). The resulting scheduled sMRM assay (Step 7) was then run to assign primary transitions (Step 8) for an extended xMRM assay where biological samples are run in triplicate (Step 9). A comprehensive suite of peak integration (Step 10) and bioinformatics tools were used for data processing, data quality metrics (Step 11), and fold-change calculations (Step 12). Finally, the data was uploaded to YPED for web-based viewing and archiving in the YPED public data repository (Step 13).

3.1 Protein Identification and Optimized MRM Peptide and Transition Selection

Three PSD fractions were prepared starting with non-frozen brain from fraction 4 (PSD A), frozen brain from fraction 3 (PSD B), and frozen brain from fraction 4 (PSD C). Each sample was analyzed via data-dependent LC-MS/MS protein identification using a 5600 Triple TOF mass spectrometer. Supporting Table 1 provides a summary of the Mascot peptide/protein identification data. Each sample identified 824, 836, and 1035 rodent proteins respectively with an overlap of 562 proteins among all three samples (Supporting Figure 1). These results are consistent with other previous studies of PSD proteins [26-31].

An important component of the workflow was the consistency between results for MS/MS peptide spectra obtained on the 5600 Triple TOF and those from the 5500 QTRAP (e.g., Supporting Figure 2). This contrasted with substantial differences in peptide MS/MS spectra acquired on Thermo Scientific Orbitrap VELOS mass spectrometers using either Ion-Trap (CID) or Higher-Energy Collisional Dissociation (HCD) (data not shown). This conclusion was supported by analysis of a yeast tryptic digest using LTQ-Orbitrap VELOS, AB Sciex 5600, and 5500 QTRAP platforms. The ratios of the mean and median dot-products for the MS/MS peak intensities of 492 tryptic peptides on the 5500/5600 platforms were 0.90 and 0.94 respectively as compared to 0.82 and 0.88 respectively for the 5500/Velos (HCD) instruments. While 86% of the dot-product ratios for the 5500/5600 instruments were above 0.8, only 66% of the dot-product ratios for the 5500/Velos (HCD) instruments met this criterion. The very similar peptide MS/MS spectra obtained on the 5500/5600 instruments undoubtedly results from their nearly identical front end quadrupoles (Q0, Q1, and Q2).

An additional key requirement for creating highly multiplexed scheduled MRM methods was consistent LC retention times across samples for each peptide. Supporting Figure 3 shows the retention time correlation of the 5600 TripleTOF and the 5500 QTRAP instruments when monitoring 26 Spectrin Beta Chain peptides (SPTB2) present in a rat PSD sample that are spread throughout the gradient. An R2 value of 1.0 between the 5500 QTRAP and 5600 TripleTOF was observed ensuring transfer of retention times from system to system and obviating the need for retention time calibration between these two platforms.

3.2 Extended MRM (xMRM) on the 5500 QTRAP

The results from the scheduled MRM runs that were used to generate the initial PSD LC-MRM assay showed that too many transitions were concurrently being acquired in numerous parts of the gradients, thus leading to very short dwell times and subsequently low signal/noise extracted ion chromatograms. To address this challenge, we added intelligence-based MRM acquisition logic to the 5500 QTRAP methods to improve both result quality and assay robustness (termed extended or xMRM).

The first aspect of xMRM is the ability to use variable acquisition windows throughout the run. For example, we used wider scheduling windows for early eluting peptides that have larger variation in their retention times, thus ensuring we did not miss acquisition due to the peptide eluting outside the scheduled window. Another potential application of this feature would be the use of expanded windows for wider peaks eluting later in the gradient.

A second feature, “Triggered xMRM”, enabled monitoring one or more designated primary transitions throughout each of their entire scheduled window, while secondary MRM for each peptide were only monitored if the primary MRM exceeded a threshold that was set at 200 counts. This approach reduced the number of MRM transitions being monitored at any given time, thus improving dwell time while decreasing cycle time (Supporting Figure 4). In all cases xMRM decreased the cycle time and increased the dwell times by 63-68% for peptides eluting between 15-45 min. As anticipated from the increased dwell times, xMRM improved the signal/noise ratio and this effect became more pronounced at limiting peptide concentrations. To assess this directly, decreasing amounts of the 314 stable isotope labeled peptide standards (SIS) mixture were analyzed on the 5500 QTRAP mass spectrometer using either sMRM or xMRM. As shown in Supporting Figure 5, at the 1.95 fmol level xMRM provided a median S/N that was more than twice that observed with sMRM and this enabled integration of 44% more transitions (i.e., 543 transitions for xMRM as compared to 376 for sMRM). Assuming that the Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ) requires a S/N of at least 5, the median LLOQ for the transitions in the PSD assay is about 8 fmol. Based on a dilution study carried out with 30 SIS peptides from 10 PSD proteins (data not shown), the PSD assay is linear over at least 4 orders of magnitude.

A third feature of xMRM, “Time Slip”, enabled real time, automated extension of scheduled windows for peaks that have not yet finished eluting at the end of their scheduled window – due perhaps to instability in their retention times (Supporting Figure 6A and B). This approach allowed smaller windows to be used while still capturing the tail of each LC-MRM peak and was robust to most shifts in retention time.

After converting the sMRM method, the final label-free xMRM method (Supporting Table 2, Assay Development, Step 3) consisted of 1697 transitions for quantitation of 112 proteins from 337 peptides respectively using 5 transitions/peptide and 4 stable isotope peptide internal standards as a quality control for instrument response (Supporting Table 3). We used the final label-free PSD xMRM assay to quantitate six rat cortex PSD biological replicates generated (named PSD Cortex 1-6) in triplicate with 1697 transitions in each run for a total of 30,546 transitions (Supporting Table 2, Data Collection, Set 1). Supporting Figure 7 outlines how the six PSD cortex samples were prepared and highlights some of the technical variation that might introduce differences in protein/peptide levels. For example, PSD1 was prepared on day 1, PSD2 and PSD3 on day 2, and PSD4, PSD5, and PSD6 on day 3. In addition, the day 2 samples (PSD2 and PSD3), were left on ice for 8 hours prior to ultracentrifugation, thus using both R and MATLAB fold change analysis tools for the plots and calculations we explored any sample preparation effects that might have resulted from the preparation of these six biological replicate samples over three days (see “Calculating Fold Change” section below for the results of these analyses).

3.3 Peak Integration

For the 25 assay development runs and initial sMRM runs, we used the MQ4 peak integration algorithm from MultiQuant. This was tedious since it required that numerous peak integration parameters be optimized for each dataset and that approximately 10% of the peaks be manually integrated due to improper peak selection. In an effort to address these challenges and to acquire several peak integration confidence metrics that are useful for calculating weighted protein level fold changes (see below), automated peak modeling was added to the current MultiQuant SignalFinder algorithm so that it could be applied to large scale datasets. The resulting SignalFinder 2 (SF2) Research algorithm has advantages over other available transition peak integration algorithms in that it does not require entering any peak integration parameters and it generates several useful metrics including NGAR, Retention Time, and Signal/Noise Confidences. To evaluate the peak integration performance of SF2 we analyzed the LC-xMRM dataset from the six PSD samples using MultiQuant MQ4, MultiQuant SF2, and Skyline peak integration algorithms without carrying out any manual peak integration. Supporting Figure 8 shows that all three algorithms perform similarly with regard to peak integration and retention time deviation.

Finally, we examined the important question of the minimum number of transitions needed to optimally integrate each peptide. Data were generated by analyzing all 18 (i.e., 6 biological PSD samples × 3 technical replicates) data sets with four different MultiQuant SF2 methods that integrated from two to five transitions per peptide. Based on these analyses, correct integration of all of the transitions in the PSD assay requires at least four transitions per peptide (Supporting Figure 9). Hence, reducing the number of transitions that were monitored per peptide to three reduced the percentage of peptides whose transitions were integrated correctly (based on retention times) to 97.0%

3.4 Data quality metrics

The first data quality metric that was analyzed was the Coefficient of Variance (CV) for the triplicate technical CVs that were analyzed for each of the 6 biological PSD samples. As indicated in Supporting Figure 10 and summarized in Supporting Table 4, using a signal/noise filter of >3 (96.83% of the data) the mean and median technical CVs were 14.47% and 7.25% respectively with the former value being well below the “Best Practices” mean CV range of below 20-35% as suggested by a recent NIH Workshop [34] for research use of MRM assays for quantifying proteins.

The second data quality metric was Normalized Group Area Ratio (NGAR) (see Supporting Materials and Methods). Briefly, for each transition, the ratio of the peak area of a transition to the peak area of the first transition for the corresponding group was calculated (Supporting Figure 11). The NGAR software then divides by the average of this ratio for all samples (for a given transition). The net result was that the reported value should be close to 1.0 if the ratio of a transition to the first is constant across the samples. If not, one (or other) of the peaks was not integrated well or had some other interference. Supporting Figure 12 shows a histogram for NGAR values obtained by analyzing the entire 18 sample dataset with the green highlighted area including 79.7% of transition peaks having NGAR values within +/-25% (i.e., from 0.75-1.25). Based on the Boxplots shown in Supporting Figure 13 and the resulting NGAR values summarized in Supporting Table 5, MultiQuant MQ4 and SF2 give similar results with regard to the accuracy of peak integration and were slightly better in this regard than Skyline. Hence, 79.8% of the transitions monitored had NGAR values within +/-25% of the expected value of 1.0 when integrated with either MultiQuant MQ4 or SF2 software as compared to 76.8% with Skyline. Based on these data as well as the distribution of NGAR scores depicted in Supporting Figure 12, we implemented a NGAR criterion of +/-25%.

For a second set of more advanced data metrics, we developed an open-source R package entitled MRMandSWATHgraphics which takes MultiQuant SF2 peak integration results, including the NGAR metric, and generates numerous exploratory graphics and data quality assessments for both label-free and SIS labeled MRM datasets. This R package may be downloaded from the “Graphics for MRM and SWATH” link at this location: http://bioinformatics.dreamhosters.com/?page_id=113. All of the resulting pdf files are available as zipped files and the content of these files and other associated files is summarized in the “MRMandSWATHgraphics.pdf” file available at the above location.

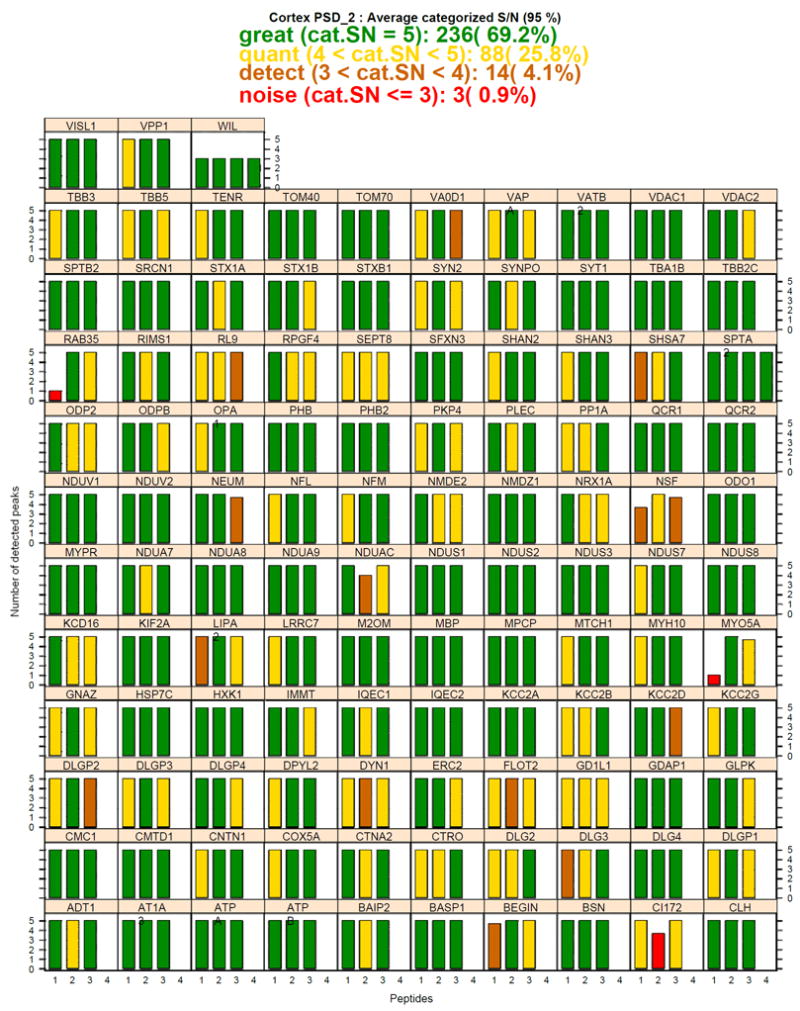

One example is the bar graph metric plot (runSpecific_barchart.pdf) shown in Figure 2 that depicts data from 1,697 MS/MS transitions that originated from 341 peptides with 4 of the latter deriving from the “WIL” internal standard. This figure efficiently captures large amounts of data in a graphical (and colorful) presentation that can be accommodated on a single page and can be quickly and easily interpreted soon after samples are analyzed, allowing low signal/noise samples to be identified so they can be rerun at higher level prior to more extensive data analysis. MRMandSWATHgraphics also performs reproducibility assessment among technical runs using pairwise scatter plots and correlation coefficients (sampleScatterPlotAndVennDiagram.pdf) (see Supporting Figure 14), heatmaps with hierarchical clustering (see Supporting Figure 15), and principle component analysis (see Supporting Figure 16).

Figure 2.

Signal to Noise Metric Bar Graph of PSD LC-xMRM assay of the combined technical replicates of PSD2. The plot is divided into 113 individual sets of bar graphs with each box representing one of 112 PSD proteins (protein name abbreviation is in upper box for each bar chart module) and 1 internal standard (WIL). Each bar graph is further sub-divided into individual bars representing the data quality of a single peptide that was interrogated based on 5 transitions/peptide (except the WIL internal standard peptides which had 3 transitions/peptide). Bar height corresponds to the number of MS/MS transitions observed for the corresponding peptide. The signal to noise ratio for each transition was transformed into a categorized integer score where 1 means the peak was not detected, 2 for S/N <3, 3 for S/N between 3 and 5, 4 for S/N between 5 and 10, and 5 for S/N > 10. Then a peptide “q-score” was generated by averaging the categorized signal/noise ratios for each underlying transition. The color of each bar depicts the peptide level q-score with red for S/N <3, brown for S/N between 3 and 5, yellow for S/N between 5 and 10, and green for S/N > 10.

3.5 Normalization

A major consideration in data normalization is that unlike LC-MS experiments, where all LC-MS peaks are measured, MRM data sets typically measure only a small subset of analytes in the sample. Hence, information may be missing that could be important for between sample normalization [35]. One way to ensure good normalization is to include some of the MRM measurements that are related to features that are not changing across the samples. If these are known a priori – then a few might be enough, but even then it is possible that these few proteins are really changing between sample groups. To address this, we included multiple normalization techniques such as Quantile, Total Area Sum (TAS), Intensity Histogram Alignment and an algorithm we developed entitled the Most Likely Ratio (MLR) [32]. MLR normalization scales the data so that the most common intensity ratio between any two samples is equal to 1.0 and assumes that the number of proteins which are not changing is larger than the number changing in any one particular way (Supporting Figure 17). The MLR algorithm also calculates sample score and measurement weight that is used in downstream fold-change analysis. The measurement weight is the likelihood that a measurement is an outlier. This likelihood is not calculated based on estimated expected response so it is not biased by use of mean or median.

Given the similar method used and the lack of any introduced biological variable, we expected that applying normalization to the six biological PSD replicates should produce no differences between each sample. Thus if any changes were found, it is most likely due to some hitherto unknown variation in sample preparation or data acquisition. Due to this assumption, each of the normalization techniques (TAS, Quantile or MLR) was expected to produce very similar results. However, as illustrated in Supporting Figure 18, the relative expression levels of many peptides differed in the PSD2 (day 2) sample compared to PSD1 (day 1), with a majority of them coming from a small number of proteins. We concluded that these differences could be explained by a sample preparation effect highlighted in Supporting Figure 7, where day 2 samples (PSD2, PSD3) were stored on ice for 8 hours prior to ultracentrifugation. In addition, the peptides differing in the PSD2 or PSD3 samples only represent about 20% of all proteins in the PSD assay, but were each changing in a similarly large amount in one direction accounting for 53% of the total area sum. Due to the fact that a small number of peptides account for such a high percentage of total area sum in PSD 2, the basic assumptions of both Quantile and TAS normalization techniques are invalid and thus they create protein expression artifacts where the majority of peptides have the same expression level but are identified as down regulated (blue ellipse in Supporting Figure 18), while in fact they were not changing. MLR normalization correctly scales the sample intensity regardless of the few intense peptides, so the majority of peptides fall along the grey diagonal line. MLR also improves discriminative power of clustering algorithms by reducing within sample variance resulting in the smallest error interval for the protein ratio which allows smaller changes to be detected (Supporting Figure 19).

3.6 Calculating Fold Change

We used confidence weighting [33] to generate protein ratios, errors and confidence scores (Supporting Figure 20), which provides a way to assess the benefit of adding extra measurements without the need for manual integration. A summary of results is shown in Figure 3, where a subset of proteins in the fold change comparison of PSD2 and PSD1 are presented at the protein (panel A), peptide (panel B) and transition (panel C) levels. (Supporting Figure 21 A-D show the complete data). The weighted statistics approach used to combine transition ratios to calculate peptide and then protein fold change ratios did not require the same number of transitions per peptide or peptides per protein across all samples, which allowed for the use of as many acceptable measurements as possible.

Figure 3.

Fold Change Result Visualizations plots. These plots allow behavior and confidence to be assessed at all levels (protein, peptide, and transition) and for all technical and biological replicates. The plots show a subset of log 10 (fold change) for PSD1 vs. PSD2 (see Supporting Figure 21 for full plots). (A) Protein Fold Change. The protein ratio is the weighted average of the peptide ratios; the average confidence is the sum of all peptide confidence values divided by the total number of peptides. For each average value an up and down error is calculated as the confidence weighted average of the distances of the corresponding peptides from the average value. Color indicates confidence with Blue = 0 and Pink = 1. Position of circle is Fold Change with confidence score coloring. Length of bar represents error in this direction and color of bar is confidence. Blue lines indicate variance range for unchanged proteins. (B) Peptide Fold Change, Confidence weighted peptide ratio derived from the individual transition ratios. The confidence is the average or median of the transition ratio confidence values. Each circle represents the fold change and confidence for a particular peptide. Color indicates confidence with Blue = 0 and Pink = 1. Circle outline color represents peptide S/N quality. (C) Transition Level Fold Change. Each line represents the response of one transition in all biological replicates. Color of the line indicates confidence with Blue = 0 and Pink =1. Length indicates relative fold change (log 10) of each transition across the three biological replicates. 0 to 1 = up regulation 0 to -1 = down regulation. Green diamonds represent signal/noise quality (0 to 1) and Blue circles, integration quality (0 to 1).

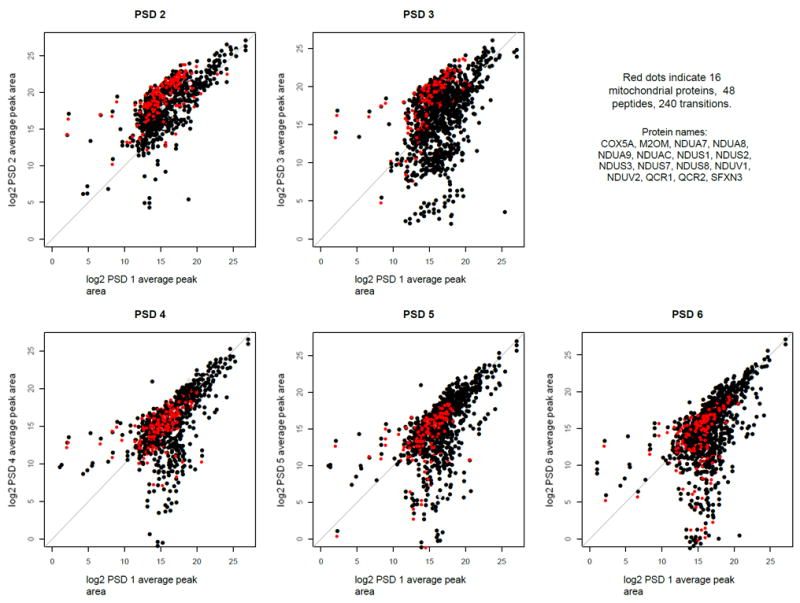

We used R to generate an alternative bar chart graphical representation of the fold change results (Supporting Figure 22), which used the same layout as Figure 2. A notable feature of the proteins that were up-regulated in the PSD2/day 2 samples was that almost all were mitochondrial proteins. The expression level of mitochondrial proteins was further assessed in the day 1, day 2, and day 3 PSD samples (Figure 4). When the PSD3 sample that also was prepared on day 2 was compared to PSD1, the same 16 mitochondrial proteins as in the PSD2 sample were increased 4-fold. This effect was not seen when the day 3 biological replicates (PSD4, PSD5, and PSD6) were compared to PSD1.

Figure 4.

Extended MRM (xMRM) log 2 scatter plots between PSD1 and the other five PSD biological replicates. After MLR normalization the log2 average peak areas were computed for each transition from each of the three technical replicates for each biological sample. Log2 average peak area (transition-level) of one of the five PSD samples was plotted on the y-axis in these graphs against the log2 average peak area of the PSD 1 sample that was used as a common “baseline”. The grey line indicates the 45-degree diagonal. The red dots represent 240 transitions in 48 peptides from 16 mitochondrial proteins whose confidence-weighted, average peak areas were more than 4-fold higher in PSD2 vs. PSD1. These same transitions were then highlighted in red in the other four scatter plots.

3.7 Assay Verification with “Gold-standard” Heavy Synthetic Peptides

To verify that the peptides selected in the label-free MRM workflow were correctly identified and that their monitored transitions did not contain interference, we synthesized 315 SIS peptides that terminate with either C-terminal heavy Arginine (Arg) or Lysine (Lys), where Lys (U-13C6;U-15N2) has an 8 Da mass difference, and Arg (U-13C6;U-15N4) has a 10 Da mass difference. The combined SIS peptide mixture was spiked into PSD1-6 and each sample analyzed in triplicate via random block order using the SIS “gold-standard” xMRM assay (Supporting Table 6) which contains 2 light and 2 heavy transitions for the 315 SIS peptides and 5 transitions for each of the remaining 23 peptides with no corresponding SIS standard. After MultiQuant SF2 peak integration, MRMandSWATHgraphics was used to generate a combined summary bar chart (Supporting Figure 23) that is similar to Figure 2 except that the SIS (heavy) and native (light) transitions are shown in two separate plots.

Supporting Figure 24 shows the retention time comparison between the label-free native and “gold-standard” SIS spiked samples. Comparing the native light transitions for all 6 PSD samples run in triplicate with the label-free and SIS “gold-standard” spiked samples produced an average retention time correlation of 0.997 between any two experiments. This validates the chromatography and peak integration of the label-free datasets and ensured accurate quantitation of each peptide. One interesting feature for future study is the small cluster of early eluting peptides around 15-22 min that previous studies have shown are more prone to run to run retention time variability [36]. To further validate both the precision and accuracy of the label-free MRM workflow, we plotted data for PSD1 vs. each of the other five PSD biological replicates for the “gold-standard” SIS labeled samples (Supporting Figure 25). The results for the levels of the light transitions for the 16 mitochondrial proteins in this experiment (red dots) were virtually identical to that obtained in the previous experiment (compare Figure 4 and Supporting Figure 25), thus validating the label-free fold change results. The “levels” of the 16 mitochondrial proteins assessed from the analysis of the spiked-in SIS peptides indicated no differences between PSD1 and PSD2 (blue dots in Supporting Figure 25). Finally, Figure 5 compares the protein fold change values for PSD2 vs. PSD1 in both label-free and “gold-standard” SIS spiked samples. The results show that each method gives nearly identical results with an R2 correlation of 0.96. We did find a few outlier proteins that have extremely large fold change values (> 16 fold) in both datasets. For example, NDUS7 (Figure 5, x-axis = 14, y-axis = 40) had a fairly large error in the fold-change measurement that resulted from this protein being virtually absent in the PSD1 sample.

Figure 5.

PSD2 vs. PSD1 Protein Fold Change Comparison between Set 1 (Label-Free) and Set 2 (“Gold standard” SIS Spiked Sample). Scatter plot contains the log 2 Protein fold change values from PSD 2 vs. PSD 1 with label-free MRM fold change on the x-axis and “Gold Standard” MRM fold change on the y-axis. Proteins were filtered with Matlab group confidence score > 0.9. A linear regression line is plotted in green with a R2 correlation of 0.96.

4 Discussion

The common approach to developing targeted proteomic assays is to synthesize and spike in a set of stable isotope dilution standards into each sample. The reasoning for adding isotopic standards is to minimize the contributions of measurement variations due to chromatography, ionization, fragmentation and detection by MS [37]. The downside of the use of isotopic standards is that as the scale of targeted assays increases isotopic standards become costly to produce, require additional mass spectrometer runs for optimization, and increase the complexity of the sample, data collection, and data analysis. Given these challenges we have designed a label-free targeted proteomics workflow which can develop relative quantitative MRM assays for more than 100 proteins in a single injection without the need for stable isotope dilution standards.

To achieve these results we had to make improvements to all stages of the targeted proteomics workflow. Using peptides from the highly abundant α-Spectrin protein, we eliminated the need for peptide retention time calibration standards such as iRT [38]. Our methodology also enabled rapid conversion of shallower gradient discovery runs (180 min) into steeper and shorter gradient LC-MRM runs (90 min) while maintaining an extremely high retention time correlation of 1.0 between these platforms and without compromising throughput and sensitivity. We implemented a targeted proteomics module in the Yale Protein Expression Database (YPED) for automated MRM assay development. A novel feature is YPED ranking of candidate peptides (previously identified in IDA analyses) that is based on their relative frequency of occurrence numeric ranking in the YPED database. With 885,634 distinct proteins including 25,696 human and 22156 mouse (as of 10/13/2014, YPED provides an extremely powerful tool to support the development of MRM analyses like that for PSD and its Repository provides for the archival of the resulting data (e.g. see Supporting Figure 26 to retrieve data from this study).

We improved on sMRM by developing xMRM data collection (Supporting Table 7). Two of the key xMRM features are variable windows and “triggered” acquisition of secondary transitions. By enabling use of wider windows for early and later eluting peaks, smaller windows can be used for the majority of peaks that permits scheduling more transitions. Triggering of secondary transitions simultaneously reduced cycle time while increasing dwell time. The decreased cycle times allowed more transitions to be monitored/run which helped to address the frequent challenge of sMRM methods running out of cycle or dwell time that, in turn, require many other large scale MRM assays [18-22, 39] to either carry out multiple injections/sample, thus increasing both the mass spectrometer time and the required amount of sample, or to monitor fewer than the four transitions per peptide that our analyses showed are needed for optimum peak integration. As anticipated from the increased dwell times, xMRM improved the median signal/noise ratio by more than two-fold at limiting peptide concentrations. The xMRM approach enabled data to be collected on 1697 transitions with >95% of these transitions having signal intensities that are above the limit of quantitation (Signal/Noise > 5). Having such high quality data enabled all five transitions to be used for data quality assessment and fold change quantitation.

A third improvement was in the area of peak integration. With the ability to generate >30,000 transitions in a single dataset (e.g., 18 samples = 3 technical replicates each of 6 biological replicates), it was no longer practical to manually inspect and then re-integrate peaks that had been incorrectly integrated, thus any miss-integrated peak would have been carried forward and would reduce the statistical power and accuracy of downstream fold change analysis. To meet this challenge we used a more advanced peak integration algorithm, SF2, which generates a peak model based on all of the datasets that it then applies to each sample. Most importantly, SF2 generates several useful metrics that are not computed by other peak integration algorithms and that all contribute to calculations of weighted protein level fold changes. The weighting was designed so that including potentially poor quality measurements should affect only the corresponding result confidence score, not the value of the fold change. Thus, the more data that is included in the analysis, the better the data can be modeled and any changes in protein level will have higher confidence weighting. Thus the combined use of MLR and weighted variance fold-change analysis supplant the need for data review prior to analysis. Another improvement was at the level of data quality assessment metrics. Utilizing five empirical transitions to calculate an NGAR score reduced the need to collect decoy transitions [40], thus allowing monitoring of more transitions/run from more peptides and proteins which in turn improved results obtained with the weighted fold-change analysis algorithm that was implemented. Based on the observed distribution of NGAR scores, we recommend use of an NGAR criterion of +/-25% which enabled use of ~80% of the transitions monitored in this study.

We incorporated different methods of data normalization and fold-change analysis into the automated data analysis. For any proteomic analysis we wanted to evaluate biological variability while reducing measurement variability through normalization. The difficulty is that there are inherent measurement errors and limits in mass spectrometry proteomic data that result, for instance, from missing data effects and interference problems. For example, since we measured 3 peptides as surrogates for each protein’s abundance, we only have a small portion of the protein data and must assume that the selected peptides are representative of protein abundance. This same model of using high intensity transitions from abundant peptides as protein surrogates has been shown to perform well by others [41, 42]. Overall the MLR normalization method used here is able to automatically identify peptides and transitions that are suitable for sample normalization. This is true even in the presence of a large number of relatively poor or missing measurements or when the assumption that the ‘majority of the proteins do not change’ is not satisfied. Following appropriate normalization procedures together with weight-modeling of measurement reliability enabled unbiased detection of differentially expressed peptides and proteins and revealed experimental variability.

Another factor to consider before differential expression analysis is to examine any non-biological effect due to the experimental protocol. For example, minor changes in sample preparation protocol or day of procedure may introduce unwanted variation. Based on the results from the analysis of 6 PSD biological replicates, we concluded that the increased level of a group of mitochondrial proteins in the PSD2 and PSD3 samples that were prepared on day 2 likely resulted from a change in the experimental procedure. Additional studies are underway to test this hypothesis. “Day effects” like this can be particularly critical if the batch effects are correlated with the main effect of interest [43]. During each experiment, it is thus helpful to record information, such as laboratory conditions, personnel, or reagent lots. When a batch effect is present, it can be adjusted by various approaches including a linear model framework commonly used for microarrays [44].

Recent literature has shown a protein level correlation of approximately 0.9 between SRM and MS-based label-free shotgun using a gold standard “Leptospria” data dataset [45]. Our comparison of label-free xMRM versus “gold-standard” xMRM assay using SIS peptides showed even better results with a retention time and fold-change correlations of 1.0 and 0.94 respectively. Our assay development adds to a growing number of examples where Scheduled LC-MRM assays are being designed to interrogate the level of expression of up to about 150 proteins [15, 17-22] in a single assay. As summarized in Supporting Table 8, single injection LC-MRM assays have been developed to quantify 142 proteins in human plasma and 56 proteins, including 49 candidate biomarkers, in mouse plasma from a mouse model of breast cancer [21]. One of the assays reported by Kennedy et al [22] enabled the quantitation of 85 proteins in human cell lines. Other MRM assays that quantified >25 proteins include an LC-MRM assay that used 135 stable isotope labeled peptide standards and one transition/peptide to quantify 67 putative biomarkers of cardiovascular disease in 90 human plasma samples [19]. In addition, one of the assays reported by Huttenhain et al [18] interrogated the level of expression of 34 human proteins in depleted plasma based on an average of 5.4 transitions/protein.

The PSD assay monitors 2.4x more transitions/run and is 2.8-fold more rigorous (i.e., in terms of the number of transitions/protein that are monitored) than other published LC-MRM proteome assays (Supporting Table 8) that we have found that have been used to monitor naturally occurring protein concentrations in human or mouse tissues or plasma/serum. Scientifically, the PSD MRM assay can be used to support a wide range of important neurobiological research that ranges from increasing our understanding of the molecular basis for learning to that for many diseases. Indeed, 269 diseases that include common neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s), adult and childhood cognitive disorders such as mental retardation, motor disorders such as ataxia or dystonia, epilepsies and many rare diseases are caused by mutations in genes for PSD proteins [31]. As one example, a recent study implicates de novo mutations in PSD proteins in the etiology of schizophrenia and, by extension, autism and intellectual disability [46] . The PSD MRM assay should be extremely useful for helping to understand how mutations in selected PSD proteins disrupt synaptic mechanisms and affect brain function to produce psychopathology. With regard to widespread use of the PSD and other large scale MRM assays, it is very promising that a multi-site study involving eight laboratories across the United States found that MRM assays are highly reproducible within and across laboratories and instrument platforms, and are sensitive to low μg/ml protein concentrations in unfractionated plasma [47]. The novel improvements described in this study represent a significant advance with regard to providing the highly automated, robust MRM assays needed to analyze the very large numbers of samples required to validate potential disease biomarkers and to extend this technology to the point of being able to interrogate the level of expression of complete proteomes.

Using the described workflow, we are currently applying this methodology to human urine and human red blood cell proteomes. In addition, with the development of extended MRM data acquisition logic we should be able to double the number of transitions and proteins collected in a single injection MRM assay. Finally, the majority of the assay workflow can directly be applied to data-independent analysis such as SWATH [48], where the potential for performing both discovery and quantitation in a single injection analysis can be realized. For example, our MRMandSWATHgraphics R script already has coding to accept Peakview data exported from SWATH data analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH grants to the Yale NIDA Neuroproteomics Center (P30 DA018343, NIDA), NIDA (DA10044), NIDDK (K01 DK089006), and the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (ULRR024139, CTSA/NCRR).

Abbreviations

- FDR

False Discovery Rate

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography MS/MS

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- LC-MRM

liquid chromatography multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem MS

- NGAR

Normalized Group Area Ratio

- PSD

Post-Synaptic Density

- SIS

stable isotope–labeled internal standard

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- YPED

Yale Protein Expression Database

Footnotes

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picotti P, Bodenmiller B, Aebersold R. Proteomics meets the scientific method. Nature Methods. 2013;10:24–27. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shifman MA, Li Y, Colangelo CM, Stone KL, et al. YPED: a web-accessible database system for protein expression analysis. Journal of Proteome Research. 2007;6:4019–4024. doi: 10.1021/pr070325f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shifman MA, Sun K, Colangelo CM, Cheung KH, et al. YPED: a proteomics database for protein expression analysis. AMIA … Annual Symposium Proceedings / AMIA Symposium; AMIA Symposium; 2005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck M, Schmidt A, Malmstroem J, Claassen M, et al. The quantitative proteome of a human cell line. Molecular Systems Biology. 2011;7 doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wisniewski J, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nature Methods. 2009;6:392–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundberg E, Uhlen M. Creation of an antibody-based subcellular protein atlas. Proteomics. 2010;10:3984–3996. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm M, Schlegl J, Hahne H, Moghaddas Gholami A, et al. Mass-spectrometry-based draft of the human proteome. Nature. 2014;509:582–587. doi: 10.1038/nature13319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MS, Pinto SM, Getnet D, Nirujogi RS, et al. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature. 2014;509:575–581. doi: 10.1038/nature13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooks R. Multiple Reaction Monitoring in Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry for Direct Analysis of Complex Mixtures. Analytical Chemistry. 1978;50:2017–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shushan B. A review of clinical diagnostic applications of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2010;29:930–944. doi: 10.1002/mas.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keshishian H, Addona T, Burgess M, Kuhn E, Carr SA. Quantitative, multiplexed assays for low abundance proteins in plasma by targeted mass spectrometry and stable isotope dilution. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:2212–2229. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700354-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onisko B, Dynin I, Requena JR, Silva CJ, et al. Mass spectrometric detection of attomole amounts of the prion protein by nanoLC/MS/MS. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2007;18:1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillette MA, Carr SA. Quantitative analysis of peptides and proteins in biomedicine by targeted mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2013;10:28–34. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx V. Targeted Proteomics. Nature Methods. 2013;10:19–22. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Method of the Year 2012. Nature Methods. 2013;10:1. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Percy AJ, Chambers AG, Yang J, Borchers CH. Multiplexed MRM-based quantitation of candidate cancer biomarker proteins in undepleted and non-enriched human plasma. Proteomics. 2013;13:2202–2215. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hüttenhain R, Soste M, Selevsek N, Röst H, et al. Reproducible Quantification of Cancer-Associated Proteins in Body Fluids Using Targeted Proteomics. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domanski D, Percy A, Yang J, Chambers A, et al. MRM-based multiplexed quantitation of 67 putative cardiovascular disease biomarkers in human plasma. Proteomics. 2012;12:1222–1243. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Percy AJ, Chambers AG, Yang J, Hardie DB, Borchers CH. Advances in multiplexed MRM-based protein biomarker quantitation toward clinical utility. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1844:917–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteaker JR, Lin C, Kennedy J, Hou L, et al. A targeted proteomics-based pipeline for verification of biomarkers in plasma. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:625–634. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy JJ, Abbatiello SE, Kim K, Yan P, et al. Demonstrating the feasibility of large-scale development of standardized assays to quantify human proteins. Nat Methods. 2014;11:149–155. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picotti P, Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring-based proteomics: workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nat Methods. 2012;9:555–566. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colangelo C, Chung C, Bruce C, Chung KH. Review of Software Tools for Design and Analysis of Large Scale MRM Proteomic Datasets. Methods. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng D, Hoogenraad CC, Rush J, Ramm E, et al. Relative and absolute quantification of postsynaptic density proteome isolated from rat forebrain and cerebellum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1158–1170. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D500009-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn CG, Banerjee A, Macdonald ML, Cho DS, et al. The post-synaptic density of human postmortem brain tissues: an experimental study paradigm for neuropsychiatric illnesses. PloS one. 2009;4:e5251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins MO, Husi H, Yu L, Brandon JM, et al. Molecular characterization and comparison of the components and multiprotein complexes in the postsynaptic proteome. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;97(Suppl 1):16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimura Y, Yamauchi Y, Shinkawa T, Taoka M, et al. Molecular constituents of the postsynaptic density fraction revealed by proteomic analysis using multidimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;88:759–768. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinidad JC, Thalhammer A, Burlingame AL, Schoepfer R. Activity-dependent protein dynamics define interconnected cores of co-regulated postsynaptic proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:29–41. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.019976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayes A, van de Lagemaat LN, Collins MO, Croning MD, et al. Characterization of the proteome, diseases and evolution of the human postsynaptic density. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:19–21. doi: 10.1038/nn.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert JP, Ivosev G, Couzens AL, Larsen B, et al. Mapping differential interactomes by affinity purification coupled with data-independent mass spectrometry acquisition. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1239–1245. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisson N, James DA, Ivosev G, Tate SA, et al. Selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry reveals the dynamics of signaling through the GRB2 adaptor. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:653–658. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carr SA, Abbatiello SE, Ackermann BL, Borchers C, et al. Targeted peptide measurements in biology and medicine: best practices for mass spectrometry-based assay development using a fit-for-purpose approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:907–917. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.036095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karpievitch YV, Dabney AR, Smith RD. Normalization and missing value imputation for label-free LC-MS analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl 16):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S16-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meek JL, Rossetti ZL. Factors Affecting Retention and Resolution of Peptides in High-Performance Liquid-Chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1981;211:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mani DR, Abbatiello SE, Carr SA. Statistical characterization of multiple-reaction monitoring mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) assays for quantitative proteomics. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl 16):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S16-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escher C, Reiter L, MacLean B, Ossola R, et al. Using iRT, a normalized retention time for more targeted measurement of peptides. Proteomics. 2012;12:1111–1121. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stahl-Zeng J, Lange V, Ossola R, Eckhardt K, et al. High sensitivity detection of plasma proteins by multiple reaction monitoring of N-glycosites. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1809–1817. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700132-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiter L, Rinner O, Picotti P, Huttenhain R, et al. mProphet: automated data processing and statistical validation for large-scale SRM experiments. Nat Methods. 2011;8:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva JC, Gorenstein MV, Li GZ, Vissers JP, Geromanos SJ. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:144–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500230-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ludwig C, Claassen M, Schmidt A, Aebersold R. Estimation of absolute protein quantities of unlabeled samples by selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013987. M111 013987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leek JT, Scharpf RB, Bravo HC, Simcha D, et al. Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2010;11:733–739. doi: 10.1038/nrg2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8:118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisser H, Nahnsen S, Grossmann J, Nilse L, et al. An automated pipeline for high-throughput label-free quantitative proteomics. Journal of Proteome Research. 2013;12:1628–1644. doi: 10.1021/pr300992u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fromer M, Pocklington AJ, Kavanagh DH, Williams HJ, et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature. 2014;506:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Addona TA, Abbatiello SE, Schilling B, Skates SJ, et al. Multi-site assessment of the precision and reproducibility of multiple reaction monitoring-based measurements of proteins in plasma. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:633–641. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillet L, Navarro P, Tate S, Röst H, et al. Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: a new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11 doi: 10.1074/mcp.O111.016717. O111.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.