Abstract

Mitochondrial oxidative damage contributes to a wide range of pathologies. One therapeutic strategy to treat these disorders is targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to the lipophilic triphenylphosphonium (TPP) cation. To date only hydrophobic antioxidants have been targeted to mitochondria; however, extending this approach to hydrophilic antioxidants offers new therapeutic and research opportunities. Here we report the development and characterization of MitoC, a mitochondria-targeted version of the hydrophilic antioxidant ascorbate. We show that MitoC can be taken up by mitochondria, despite the polarity and acidity of ascorbate, by using a sufficiently hydrophobic link to the TPP moiety. MitoC reacts with a range of reactive species, and within mitochondria is rapidly recycled back to the active ascorbate moiety by the glutathione and thioredoxin systems. Because of this accumulation and recycling MitoC is an effective antioxidant against mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and also decreases aconitase inactivation by superoxide. These findings show that the incorporation of TPP function can be used to target polar and acidic compounds to mitochondria, opening up the delivery of a wide range of bioactive compounds. Furthermore, MitoC has therapeutic potential as a new mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, and is a useful tool to explore the role(s) of ascorbate within mitochondria.

Abbreviations: ACR, accumulation ratio; AO, ascorbate oxidase; AFR, ascorbyl free radical; DHA, dehydroascorbic acid; DTPA, diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid; FCCP, carbonylcyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; FCS, foetal calf serum; GSH, glutathione; LAH, linoleic acid hydroperoxide; Δψm, mitochondrial membrane potential; MitoC, mitochondria-targeted ascorbate; MitoDHA, mitochondria-targeted dehydroascorbate; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive species; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; TPMP, methyltriphenylphosphonium; TPP, triphenylphosphonium; RET, reverse electron transport; RLM, rat liver mitochondria; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RP-HPLC, reverse-phase HPLC; XO, xanthine oxidase

Keywords: Lipophilic cation, Lipid peroxidation, Mitochondria, Mitochondrial targeting, Ascorbic acid, MitoPerox, MitoC

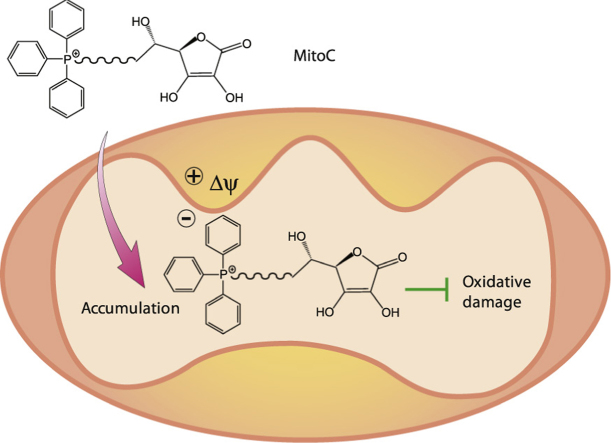

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A mitochondria-targeted ascorbate, MitoC, has been developed

-

•

MitoC is taken up by energized mitochondria and there recycled

-

•

Mitochondrial oxidative damage is decreased by MitoC

-

•

MitoC is a useful reagent to explore mitochondrial oxidative stress

Mitochondria are continually exposed to a flux of superoxide from the respiratory chain and derived reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide, that lead to oxidative damage [1]. The levels of ROS formation and oxidative damage are decreased or repaired by a battery of mitochondrial antioxidant defenses [2]. However, under many pathological conditions the capacity of the antioxidant defense and oxidative damage repair system is exceeded, leading to the mitochondrial oxidative damage that underlies pathology. Consequently, strategies to decrease this oxidative damage have considerable therapeutic potential and the selective targeting of antioxidants to mitochondria by covalent conjugation to the lipophilic triphenylphosphonium (TPP) cation is one widely used approach [3].

TPP is a membrane-permeant lipophilic cation that is rapidly accumulated several hundred-fold within mitochondria in vivo driven by the large mitochondrial membrane potential (negative inside). The most widely used mitochondria-targeted antioxidant is MitoQ [4], a ubiquinol derivative that prevents mitochondrial oxidative damage in a wide range of animal models [5] and has also been assessed in two phase II trials in humans [6], [7]. This approach has been extended to target a wide range of other antioxidants, pharmacophores and probe molecules to mitochondria in vivo[3], [8]. To date however, the compounds that have been so targeted have been hydrophobic, uncharged and hence largely act at the matrix-facing surface of the mitochondrial inner membrane. There is an unmet need to develop mitochondria-targeted antioxidants that act in the matrix. In addition, an aqueous antioxidant may also act as a redox shuttle connecting antioxidants in the mitochondrial matrix, such as glutathione, with those within the membrane, such as Vitamin E.

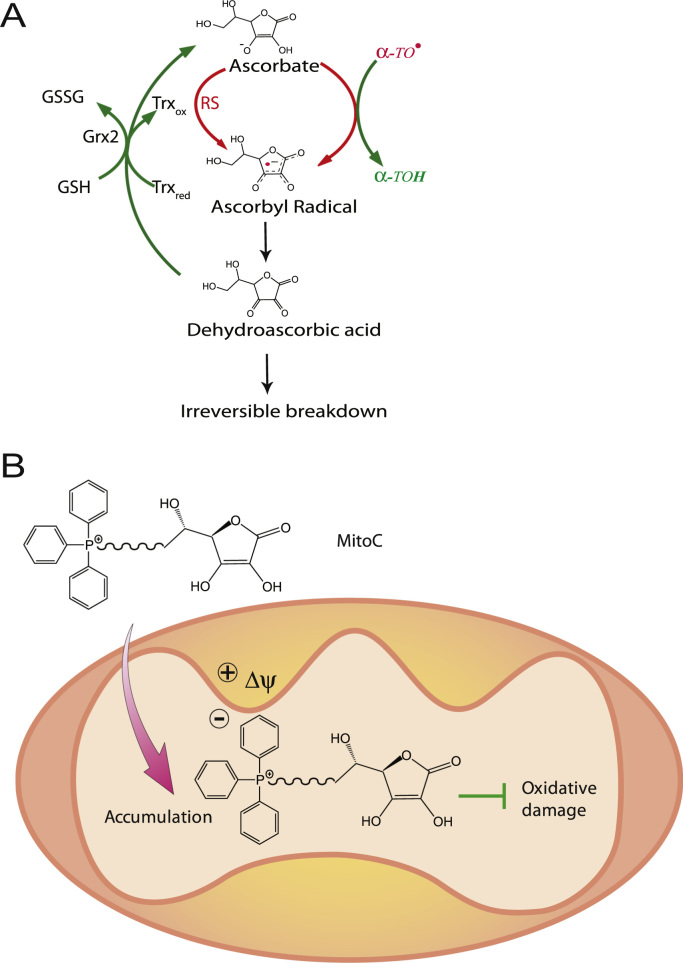

A compelling candidate for a matrix antioxidant and redox mediator is ascorbate (Vitamin C), which is highly polar and negatively charged at physiological pH (pKa 4.2 [9]). Ascorbate functions as an antioxidant in the aqueous phase through one electron donation to quench radicals, and also has an important role as a biological reductant [10]. The ascorbyl radical thus generated dismutates to ascorbate and dehydroascorbate (DHA), which is unstable and hydrolyses spontaneously if it is not rapidly reduced back to ascorbate by reductants such as glutathione [11], [12], [13] (Fig. 1A). Ascorbate also interacts with biological membranes to recycle the lipid-soluble antioxidant Vitamin E from the α−tocopheroxyl radical back to the active antioxidant [13], [14] (Fig. 1A). Thereby ascorbate links matrix reductants to antioxidant processes within the inner membrane [11]. There is a pool of ascorbate within mammalian mitochondria [15] that arises from either sodium-coupled ascorbate accumulation [16], or by uptake of DHA via the mitochondrial GLUT-10 transporter followed by reduction to ascorbate within the matrix [17]. However, the potential role(s) of ascorbate in the mitochondrial matrix have not been explored in depth and the physiological importance of ascorbate as an antioxidant and/or as a one electron reductant within mitochondria is unclear.

Fig. 1.

The redox reactions of ascorbate and the uptake of MitoC by mitochondria. (A) Antioxidant reactions and recycling of ascorbate. Ascorbate reacts with reactive species (RS) or with the α-tocopheroxyl radical (α-TO•) at the surface of the mitochondrial inner membrane by one electron donation to form the ascorbyl radical. The ascorbyl radical then dismutates back to ascorbate and dehydroascorbate (DHA), which can then either hydrolyze irreversibly or be recycled back to ascorbate by the GSH/Grx2 and Trx systems. (B) Uptake of MitoC by mitochondria. MitoC, an ascorbate linked to the lipophilic TPP cation by an alkyl chain, is accumulated several hundred fold within the mitochondrial matrix driven by the membrane potential (Δψ) and there acts as an antioxidant.

Thus there is a strong justification for developing a mitochondria-targeted ascorbate to see if this decreases mitochondrial oxidative damage and to explore the function of ascorbate within the matrix (Fig. 1B). However, it is unclear if a hydrophilic and polar carbohydrate such as ascorbate can be transported through a biological membrane by conjugation to TPP. Furthermore, as ascorbic acid has a pKa of 4.2 [9], under physiological conditions a TPP-conjugated ascorbate would be a zwitterion, whose neutrality may prevent uptake into mitochondria driven by the membrane potential [18], [19]. Therefore, in addition to its potential utility, the development of a mitochondria-targeted ascorbate presents interesting challenges, which, if overcome, would expand the groups that can be targeted to mitochondria. Therefore here we synthesized TPP-conjugated ascorbate variants (MitoC) differing in lipophilicity to determine whether ascorbate can be targeted to mitochondria. We show that the 11-carbon version of MitoC is accumulated by energized mitochondria and is continually recycled to its active antioxidant form by the mitochondrial glutathione and thioredoxin systems, making MitoC a far more effective mitochondrial antioxidant than ascorbate itself.

1. Materials and methods

1.1. Synthetic chemistry

All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise stated. 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectra were acquired on Varian AR 500 or MR 400 spectrometers. Chemical shifts are given in ppm on the δ scale referenced to the solvent peaks. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker microTOF electrospray mass spectrometer. HPLC analysis was carried out using a Shimadzu prominence system on a C18 column (Phenomenex Prodigy ODS(3) 5 μm 100 Å, 250×3 mm) gradient elution 10% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to 100% ACN/0.05% TFA over 12.5 min at 0.5 ml min−1 with detection at 210 and 254 nm.

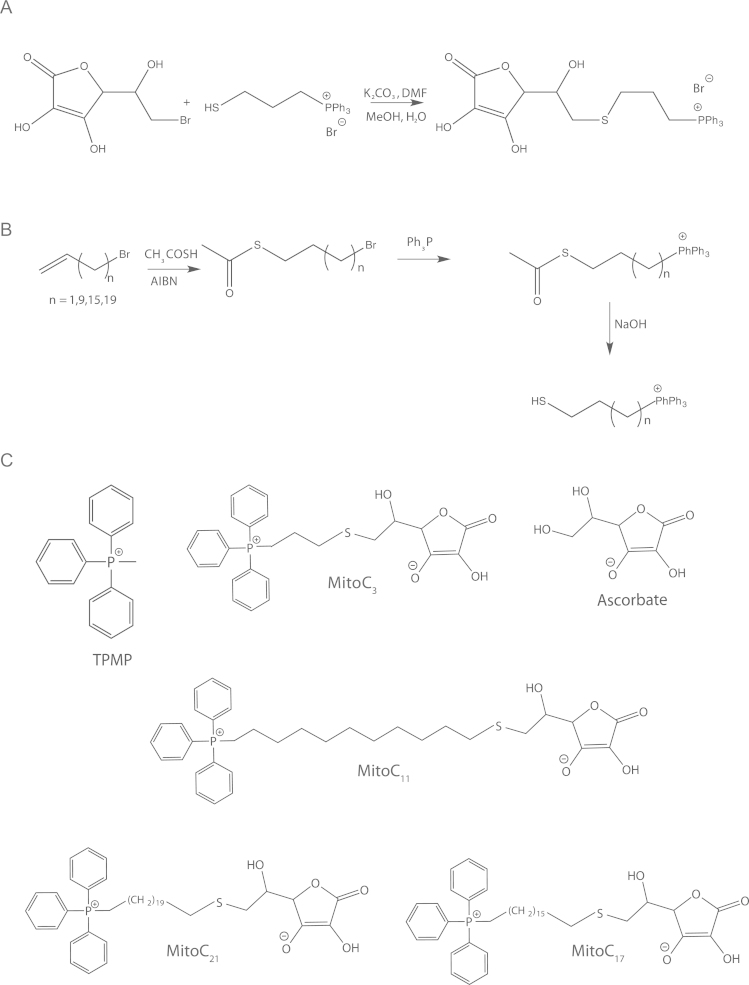

Attachment of a TPP function at C-6 was achieved using a connecting sulfur atom. This was based on literature precedence and our previous experience with TPP thiols. Reaction of 6-bromo-6-deoxy-L-ascorbic acid with TPP propylthiol [20] using a modification of the published procedure [21], but avoiding the use of sodium hydroxide, worked effectively (Fig. 2A). TPP thiols for the longer chain variants were produced from the corresponding bromoalkene [22] (Fig. 2B). However, as initial attempts to isolate long chain TPP thiol compounds from the hydrolysis reaction gave significant disulfide formation, we used an initial basic pH to hydrolyze the TPP thioacetate and then rapidly decreased the pH. The bromoalkene precursors [23], [24] for the C17 and C21 compounds were prepared by haloalkylation of the Grignard reagent prepared from 11-bromoundecene [25]. Details of the synthetic chemistry are given in the Supplemental Materials.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis and structures of MitoC variants. (A) Synthesis of MitoC3. The synthesis of MitoC3 shows the reaction between bromoascorbic acid and TPP-propylthiol (B) Synthesis of the TPP-alkylthiols of different lengths. By altering the lengths of the alkyl chain [TPP(CH2)nSH] a series of MitoC compounds of different hydrophobicities can be generated. (C) Structures of the compounds investigated. The simplest TPP cation (TPMP), ascorbic acid and the MitoC variants: MitoC3, MitoC11, MitoC17 and MitoC21.

1.2. Characterisation of MitoC

Stock solutions of TPP compounds were made up in absolute ethanol, flushed with argon and stored at –20 °C. L-ascorbic acid was used in all experiments for comparison with MitoC. Most reactions were carried out in KCl buffer (120 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2). Reversed phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) measurements were obtained using a C18 column (Jupiter 300 A, Phenomenex®) with a Widepore C18 Guard Column (Phenonmenx®), a 2 ml sample loop and a Gilson 321 pump. For this, MitoC (10 nmol) and the internal standard TPMP (10 nmol) were added to 750 µL KCl buffer and incubated at 37 °C. Samples were diluted with 250 µL buffer B (0.1% TFA in HPLC-grade ACN), filtered through a Milipore® Millex® syringe-driven filter unit (0.22 µm) and separated by RP-HPLC. A gradient of buffer A and B was run at 1 ml/min (%B): 0–5 min, 5–15%; 5–31 min, 15–100%; 31–35 min, 100–5%. Peaks were detected at 220 nm using a Gilson UV/VIS 151 spectrophotometer. TPMP and MitoC standards were used to determine elution times and peak areas were calculated using the Chart 5 (ADInstruments®) software. To assess oxidation MitoC (20 nmol) or ascorbic acid (15 nmol) was incubated at 37 °C in KCl buffer and UV absorption spectra obtained using a Shimadzu UV-2501 PC spectrophotometer. To measure the pKa we monitored changes in the UV absorbance at 265 nm for ascorbic acid (30 μM) or MitoC (15 μM) in KCl buffer at 25 °C at different pH values. The pKa values were calculated by fitting to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation,

, where AN and AI are absorbances of the protonated and ionised forms, respectively, and ApH is the absorbance at the respective pH. pKa values obtained were: 4.28±0.09 and 11.08±0.43 for MitoC and 4.36±0.29 and 11.27±0.16 for ascorbic acid.

1.3. Mitochondrial preparation

Liver mitochondria (RLM) were prepared from 6 to 13 week old female Wistar rats (up to 250 g) by homogenization followed by differential centrifugation in ice-cold 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4. Protein concentration was determined by the biuret assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Incubations were carried out in KCl buffer at 37 °C, if not otherwise stated. Mitochondrial uptake of MitoC measured using an ion-selective electrode (ISE) sensitive to the TPP moiety was done as previously described [26]. Linoleic acid hydroperoxide (LAH) was made as described [27].

1.4. Mitochondrial uptake of MitoC measured by RP-HPLC

RLM (0.5 mg protein/ml) were incubated in 4 ml KCl buffer supplemented with rotenone (4 µg/ml) and TPMP (2.5 µM) and the respective MitoC variant (2.5 µM) in open plastic tubes (Sarsted®) in a shaking water bath at 37 °C. Respiration was initiated by the addition of succinate (4 mM). When indicated FCCP (1 µM) was added 4 min later. Five min later mitochondria were pelleted by centrifugation (7500 x g for 5 min at 4 °C). Supernatants were removed and stored at 4 °C in eppendorf tubes until analysis. Mitochondrial pellets were extracted in 250 µL buffer B followed by centrifugation (7500 x g for 5 min). The supernatant (250 µL) was removed and stored at 4 °C in glass vials (Chromacol®). All samples were diluted to 25% ACN with buffer A, and separated by RP-HPLC as described above. TPMP and MitoC standards were used to determine peak areas and elution times, using the Chart 5 software (ADInstruments®). Accumulation ratios (ACR) between the mitochondrial matrix and the extra-mitochondrial environment were calculated by normalizing the peak areas to mitochondrial volume (0.5 µL/mg protein [28]) and to 4 ml for the extra-mitochondrial environment.

1.5. Oxidation and reduction of MitoC

Oxidation of MitoC and ascorbic acid was followed by the decrease in absorbance at 265 nm at 25 °C in KCl buffer. To generate a superoxide flux we used xanthine oxidase (XO, Sigma) (0.1 U/ml) and acetaldehyde (10 mM), in the presence of catalase (5 µg/ml). Reaction of MitoC and ascorbic acid was followed by coupling their reductive recycling to an NADPH-linked reductase and measuring the absorbance at 340 nm. Thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) and thioredoxin (Trx) were from Escherichia coli (Sigma), ascorbate oxidase (AO) was from Cucurbita sp. (Sigma) and His-tagged glutaredoxin-2 (Grx2) was prepared and purified as described [29].

1.6. Oxidative damage assays

To measure thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS), mitochondria (2 mg protein/ml) were incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 5 min in 100 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6 supplemented with 4 μg/ml rotenone with 10 mM succinate or 1 µM FCCP as indicated. Then 0.8 ml aliquots were mixed with 400 µl 0.5% thiobarbituric acid in 35% HClO4 and 60 µl 2% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) in DMSO, and then heated at 100 °C for 15 min, diluted with 2 ml water and extracted into 2 ml n-butanol. TBARS were determined fluorometrically (λexcitation=515 nm; λemission=553 nm) and expressed as nmol malondialdehyde (MDA) by comparison with a standard (1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane) processed as above. MitoPerox fluorescence was measured using a Shimadzu RF-301 PC fluorimeter ((λexcitation=495 nm; λemission=520 nm; slit widths 3 nm; scan speed, fast). For aconitase inactivation, mitochondria (2 mg protein/ml) were incubated with succinate (10 mM) to induce reverse electron transfer (RET) and inhibited by rotenone (4 μg/ml) [30], or incubated with paraquat. Aconitase activity was assayed in a 96-well plate as described previously [31]. Briefly, aliquots (10 µl) of snap-frozen mitochondrial incubations were incubated in 190 µl Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 7.4), MnCl2 (0.6 mM), sodium citrate (5 mM, pH 7.0), NADP+ (0.4 mM), Triton X-100 (0.1% v/v), and isocitrate dehydrogenase (0.8 U ml−1) in triplicate at 30 °C, and NADPH (ε340=6.22×103 M−1 cm−1) was monitored over 20 min at 340 nm using an ELx808 Ultra Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments). Background NADPH formation was determined in the presence of fluorocitrate (100 μM) and was always less than 10% of the initial rate.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and hydrophobicity of MitoC3-21

To direct ascorbate selectively to mitochondria we conjugated it to the lipophilic TPP cation (Fig. 2B). As we were concerned that the polarity of the ascorbate moiety might disrupt uptake we made a series of TPP-ascorbate conjugates of varying hydrophobicities by increasing the length of the alkyl chain linking to the TPP cation [32]. Four MitoCn variants with linkers of 3, 11, 17 and 21 methylene groups were synthesized (Figs. 2A and B), and are shown in Fig. 2C, along with ascorbic acid and the simple TPP lipophilic cation TPMP. These MitoC variants eluted from a RP-HPLC C18 column in order of their hydrophobicity (Fig. 3A).

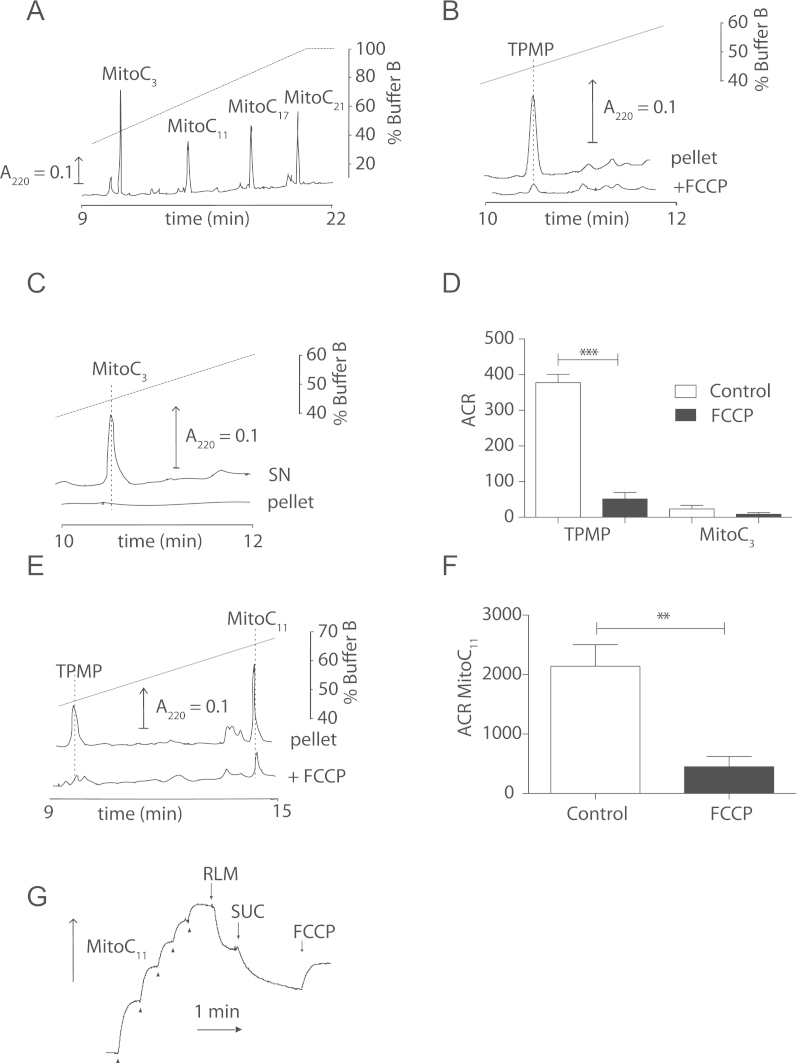

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial accumulation of MitoC variants. (A) Relative hydrophobicity of MitoC variants. RP-HPLC of a mixture of 10 nmol each of the MitoCn variants (n=3, 11, 17 and 21). (B) Uptake of TPMP into mitochondria. TPMP (2.5 μM) was incubated with mitochondria (0.5 mg protein/ml) in KCl buffer supplemented with rotenone (4 µg/ml) and were energised with succinate (10 mM)±FCCP (1 µM) and uptake assessed by RP-HPLC. (C) Lack of uptake of MitoC3 by mitochondria. MitoC3 (2.5 μM) was incubated with mitochondria as in (B) and the amounts in the mitochondrial pellet and supernatant (SN) were determined after 5 min by RP-HPLC. (D) The accumulation ratios (ACRs) of MitoC3 and TPMP. The ACRs of MitoC3 (2.5 μM) and TPMP (2.5 μM) were measured as described in (B)±FCCP. Data are means±SEM of three independent incubations. (E) Mitochondrial uptake of MitoC11. Mitochondria were incubated with MitoC11 (2.5 μM) and TPMP (2.5 μM)±FCCP as in (B) and the amounts of the compounds in the pellet determined by RP-HPLC. (F) The ACR for MitoC11 was determined as in (D). Data are means±SEM of three independent incubations. (G) Uptake of MitoC11 by mitochondria measured using an ion-selective electrode. An electrode sensitive to the TPP moiety of MitoC was inserted into KCl buffer supplemented with 4 µg/ml rotenone. After calibration with 5×1 µM MitoC (arrowheads), mitochondria (RLM) (0.5 mg protein/ml) were added, followed by 10 mM succinate (SUC) and 1 µM FCCP. This trace is representative of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (⁎⁎p<0.01, ⁎⁎⁎p<0.001).

2.2. Dependence of MitoC mitochondrial uptake on hydrophobicity

MitoC11 had pKa values of 4.28±0.09 and 11.08±0.43, compared to 4.36±0.29 and pKa 11.27±0.16 for ascorbic acid. Thus conjugation of ascorbate to a TPP cation did not affect its pKa and under physiological conditions MitoC will be a zwitterion whose neutrality may preclude uptake by mitochondria in response to the membrane potential [18], [19]. However, a weak acid conjugated to a TPP cation was taken up into mitochondria in response to the membrane potential by crossing the membrane in a protonated, monocationic form [18], [19]. Given that less than 0.1% of MitoC would be in the monoprotonated form it was unclear if uptake could occur for MitoC. A further potential limitation to the mitochondrial uptake of MitoC is whether the polarity of the ascorbate moiety, even when protonated and neutral, would prevent uptake through the inner membrane. This difficulty may arise because the ability of a TPP cation to cross a membrane is a balance between lipophilicity and polarity, with hydrophobicity enhancing uptake [18], [32]. Increasing hydrophobicity of a TPP cation can enable the threshold for membrane transport to be reached [32], therefore we assessed whether any of the MitoC variants shown in Fig. 2C were taken up by mitochondria.

Incubation of the simple TPP cation, TPMP with energized mitochondria followed by isolation by centrifugation and analysis by RP-HPLC showed extensive uptake into mitochondria that was blocked by dissipating the membrane potential with the uncoupler FCCP (Fig. 3B). In contrast, there was no uptake into mitochondria of MitoC3, which remained in the supernatant (Fig. 3C). To further quantify uptake we also measured the accumulation ratio (ACR), that is, the amount of TPMP or MitoC3 in mitochondria relative to that in the supernatant (Fig. 3D). To see if MitoC3 was not taken up due to its polarity, we next assessed the more hydrophobic MitoC11, simultaneously with TPMP to facilitate comparison (Fig. 3E). Both MitoC11 and TPMP were accumulated within energized mitochondria, and this uptake was prevented by FCCP (Figs. 3E and F). The difference in uptake between MitoC11 and MitoC3 was not due to a decrease in the pKa of MitoC3, for example caused by closer proximity of the cation, as the first pKa of MitoC3 (4.15) was very similar to that for MitoC11 (4.28). Therefore MitoC11 is taken up by mitochondria in a membrane potential-dependent manner while MitoC3 is not, presumably because of its greater hydrophilicity. MitoC17 and MitoC21 showed extensive adsorption to de-energized mitochondria (data not shown), due to their hydrophobicity, so while they are probably accumulated in response to the membrane potential, they are too hydrophobic to be easily worked with. Therefore we focused on MitoC11 and refer to it as MitoC from now on.

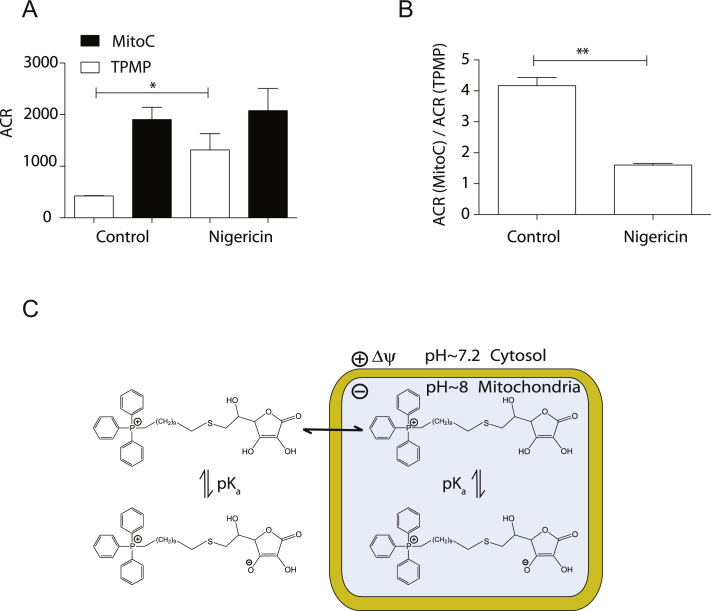

MitoC (pKa ~4.28) is most likely taken up by mitochondria as the protonated, monocationic form, as was the case for a TPP-conjugated carboxylic acid (pKa ~4.9) [19]. In that case, the accumulation of the weak acid into the basic mitochondrial matrix synergized with the membrane potential to enhance uptake [19]. To see if the mitochondrial pH gradient increased MitoC uptake we abolished the pH gradient with the K+/H+ exchanger nigericin. As nigericin increases the membrane potential to the same extent as it decreases the pH gradient, we measured the uptake of MitoC and TPMP simultaneously to control for the change in membrane potential (Fig. 4A). Nigericin increased the uptake of TPMP, due to the rise in membrane potential, but had a negligible effect on MitoC uptake, probably due to the increase in uptake due to the higher membrane potential being counteracted by the loss of the pH-dependent accumulation of its weak acid (Fig. 4A). Normalizing the uptake of MitoC to that of TPMP corrected for this effect of membrane potential; nigercin decreased the potential-corrected uptake of MitoC (Fig. 4B), hence the pH gradient enhances the accumulation of MitoC in the same way as for a TPP-conjugated carboxylic acid [19]. MitoC is taken up into mitochondria via the protonated, monocationic form, and its uptake is greater than that of the cation alone due to the pH gradient (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

MitoC uptake dependence on the mitochondrial pH gradient. (A) Effect of nigericin on the uptake of MitoC and TPMP. The ACRs of MitoC (2.5 μM) and TPMP (2.5 μM) were measured simultaneously as in Fig. 3D±nigericin (100 nM). (B) Accumulation of MitoC normalized to that of TPMP. Data in (A) and (B) are means±SEM of three independent incubations. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (⁎p<0.05, ⁎⁎p<0.01). (C) Schematic of mechanism of uptake of MitoC by energized mitochondria. A TPP cation conjugated to an ascorbate moiety generates a membrane-impermeant zwitterion and a membrane-permeant singly charged cation that is accumulated in response to Δψm. The pH gradient will further enhance the accumulation of MitoC.

2.3. Oxidation of MitoC

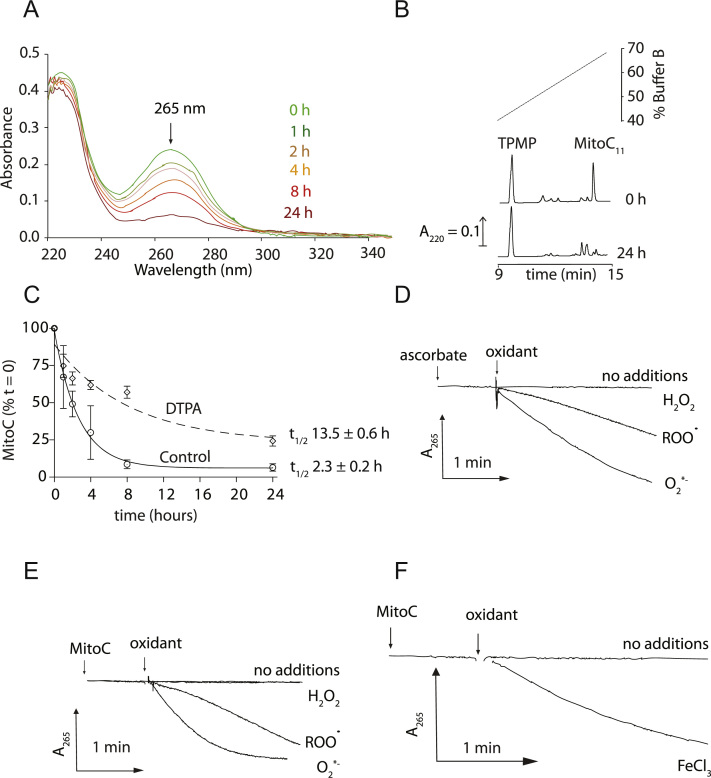

Ascorbate is a reductant and antioxidant through one electron donation, thereby generating the ascorbyl radical, which in turn dismutates to dehydroascorbate (DHA) and ascorbate (Fig. 1A). If DHA is not recycled back to ascorbate it hydrolyzes irreversibly. UV absorption showed that the ascorbate moiety of MitoC was lost under biological conditions (Fig. 5A). RP-HPLC also showed extensive degradation of MitoC with a half-life of ~2.3 h (Figs. 5B and 6C). MitoC loss was slowed by chelating redox-active metals (Fig. 5C), consistent with its oxidation to MitoDHA followed by spontaneous hydrolysis.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of MitoC oxidation. (A) UV-scanning spectra of MitoC. Spectra of (15 μM) of MitoC11 in KCl buffer were measured over time. (B, C) Oxidation of MitoC11 measured by RP-HPLC. MitoC11 (10 μM) was incubated in KCl buffer±DTPA (5 mM) with 10 µM TPMP as an internal standard. At various times samples were analyzed by RP-HPLC. (C) Shows the levels at t=0 and t=24 h and (D) shows the full time course where data are means±SEM of three experiments. (D-F) Reaction of ascorbate or MitoC with oxidants. MitoC (20 µM) or ascorbate (20 µM) was incubated in KCl medium and the decrease of absorbance at 265 nm measured. Additions were H2O2 (100 µM), ROO• (generated by spontaneous homolysis of 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (10 mM)), superoxide or FeCl3 (30 µM). Generation of superoxide was initiated by 10 mM acetaldehyde in the presence of xanthine oxidase (0.1 U/ml) and catalase (5 µg/ml). The oxidation of ascorbate and MitoC by superoxide was prevented by including Cu, Zn SOD (100 U/ml).

Fig. 6.

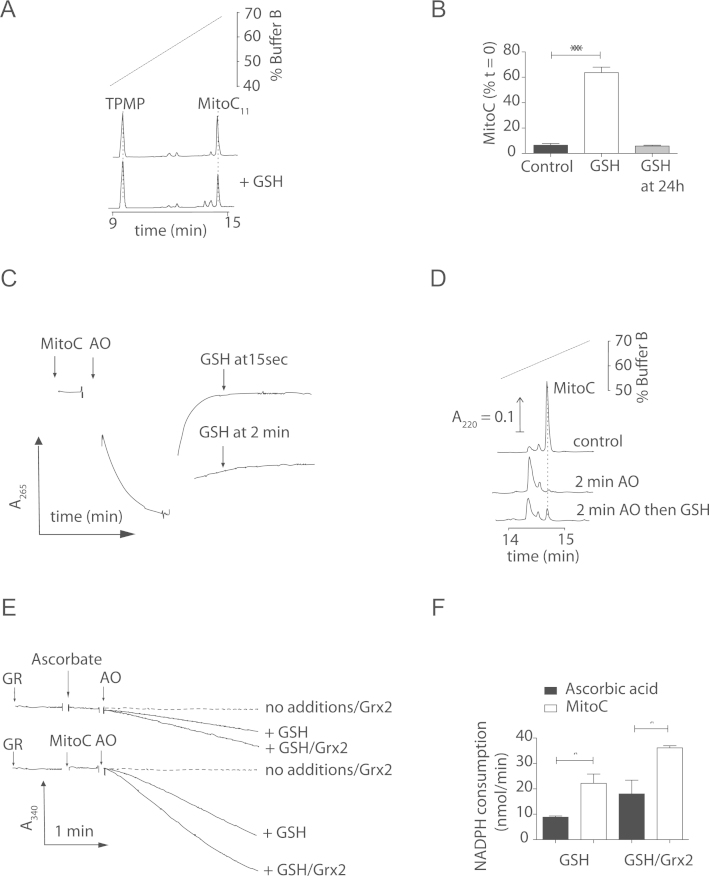

Recycling of MitoC by glutathione. (A) RP-HPLC assessment of MitoC oxidation. MitoC (10 nmol) and a TPMP internal standard (10 µM) after 0 or 24 h in KCl buffer with DTPA (5 mM) and GSH (10 mM). (B) Quantification of the effect of GSH on MitoC stability. MitoC content normalised to TPMP after 24 h±GSH as described in (A), or when GSH was added after 24 h incubation. Data are means±SEM of three experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student's t-test (⁎⁎⁎p<0.001). (C) Regeneration of oxidised MitoC by GSH. Time course of absorbance at 265 nm for MitoC (20 µM) in KCl buffer. Oxidation was initiated by the addition of AO (1 U/ml). After complete oxidation GSH (10 mM) was added. (D) The experiment in (C) was repeated and analyzed by RP-HPLC. RP-HPLC chromatogram of MitoC (30 µM) after oxidation with AO as in (C). (E) Recycling of MitoC or ascorbic acid by the GSH/Grx2 system. Recycling was followed at 340 nm by the oxidation of NADPH (0.3 mM) by GR (0.4 U/ml) with either GSH (10 mM), or GSH (10 mM) and glutaredoxin (Grx2; 1 U/ml). After 3 min of equilibration test compound (20 µM) was added and oxidation initiated by the addition of AO (1 U/ml). Grx2 in the absence of GSH was indistinguishable from “no additions” and this trace has been omitted. (F) Rate of NADPH oxidation by glutathione reductase. The initial rate of NADPH oxidation following addition of AO determined in (E) was quantified. Data are means±SEM of three independent incubations. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student's t-test (⁎p<0.01).

We next assessed how MitoC reacts with physiological oxidants by observing its ascorbate moiety at 265 nm (Figs. 5D and E). Both ascorbate and MitoC are rapidly oxidized by superoxide and alkyl peroxyl radicals, but not by hydrogen peroxide (Figs. 5D and E). Ascorbate reduces transition metals maintaining their bioavailability [10], and MitoC also reduced ferric iron (Fig. 5F). Therefore conjugation to TPP does not impair ascorbate redox chemistry, so MitoC should be an effective antioxidant and reductant.

2.4. Recycling of MitoC

To be an effective antioxidant in vivo the unstable MitoDHA formed following one electron reduction by MitoC must converted back to MitoC before it decomposes. To see whether MitoC could be recycled we assessed the effect of glutathione (GSH) on MitoC oxidation over 24 h (Fig. 6A). MitoC was maintained in its active, reduced state by the presence of GSH during the incubation, however addition of GSH at the end of the incubation did not restore MitoC (Fig. 6B). To rapidly oxidize MitoC to MitoDHA we used ascorbate oxidase (AO, L-ascorbate:O2 oxidoreducatse, EC 1.10.3.3) [12], which converted MitoC to MitoDHA, as measured by UV absorbance (Fig. 6C) and RP-HPLC (Fig. 6D). GSH added immediately after MitoC oxidation could restore MitoC (Figs. 6C and D), but not when added 2 min later (Figs. 6C and D). To further assess MitoC recycling by GSH, we coupled GSH oxidation to NADPH consumption through glutathione reductase (Figs. 6E and F). Addition of AO led to GSH oxidation as MitoDHA was recycled back to MitoC (Figs. 6E and F). The mitochondrial glutaredoxin2 isoform (Grx2), which can act as a DHA reductase utilizing GSH [2], [32], [33], [34], enhanced the recycling of MitoDHA after AO oxidation (Figs. 6E and F). These findings are consistent with GSH and Grx2 recycling MitoDHA back to MitoC before its irreversible hydrolysis (t1/2 ~5 min).

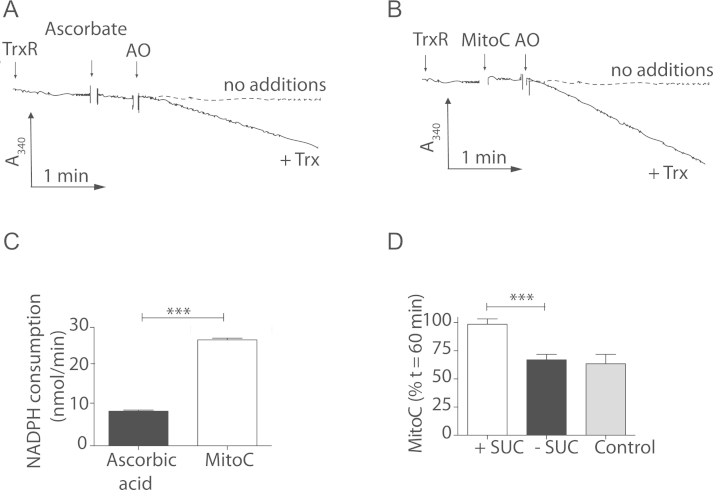

The thioredoxin (Trx) system can also recycle DHA to ascorbate [35]. To assess whether Trx could also recycle MitoC we incubated ascorbate or MitoC in the presence of E. coli thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), coupling MitoDHA recycling to NADPH oxidation (Fig. 7). When MitoC was oxidized by AO there was no recycling by TrxR, although the mammalian form of TrxR, which is a selenoenzyme unlike that from E. coli, is likely to directly reduce MitoDHA [35]. Trx addition increased NADPH oxidation (Fig. 7A-C), suggesting MitoDHA is recycled back to MitoC by direct reaction with Trx, which is then recycled by TrxR. Thus within mitochondria MitoDHA will be recycled back to MitoC by the GSH/Grx2 and Trx/TrxR systems. Supporting this, incubating MitoC with energized mitochondria prevented its degradation (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Recycling of MitoC or ascorbic acid by thioredoxin. (A, B) Recycling by thioredoxin. Ascorbic acid (A) or MitoC (B) was followed by the oxidation of NADPH (0.3 mM) at 340 nm by TrxR (1 U/ml)±Trx (1 U/ml). After 3 min of equilibration test compound (20 µM) was added and oxidation initiated by the addition of AO (1 U/ml). (C) Rate of NADPH oxidation by TrxR. The initial rate of NADPH oxidation following addition of AO determined in (A) and (B) were quantified. Data are means±SEM of three independent incubations. (D) Effect of incubation with mitochondria on MitoC redox stateMitochondria (0.5 mg protein/ml) were incubated in rotenone (4 µg/ml) supplemented KCl buffer that contained MitoC (10 µM) in the presence (white bar), or absence (black bar) of succinate (10 mM). The grey bar shows MitoC incubated without mitochondria. Ratios of A.U.C. of MitoC expressed as percentage loss. After 60 min incubation the amount of MitoC remaining was assessed by RP-HPLC. Data are means±SEM of independent incubations (n=3-5). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test (⁎⁎⁎ P<0.001).

2.5. Prevention of mitochondrial oxidative damage by MitoC

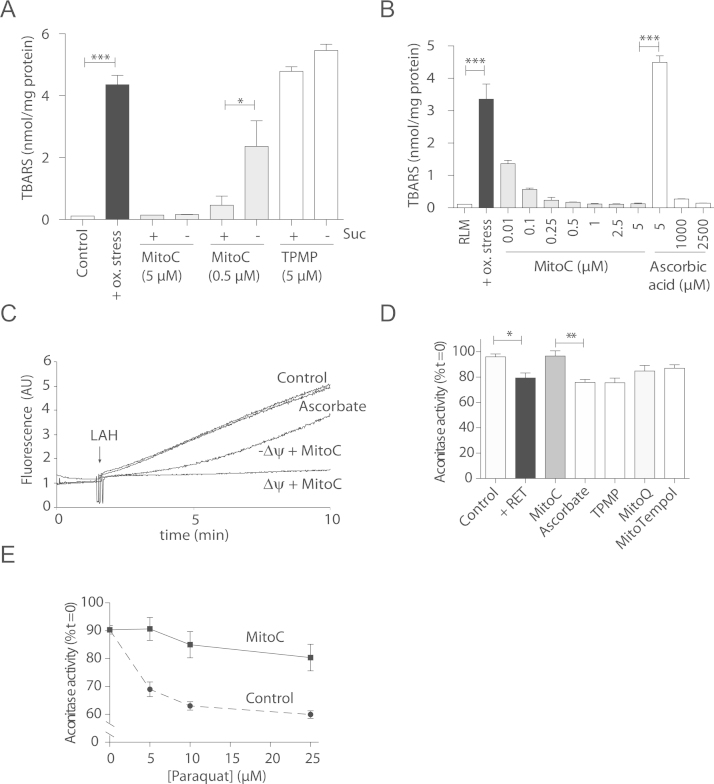

MitoC is accumulated by mitochondria, can sequester reactive species and then be recycled. To see if these properties made MitoC an effective mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, we assessed whether it could protect against lipid peroxidation (Fig. 8A). To do this we induced lipid peroxidation in mitochondria and then measured its extent by quantifying TBA reactive species (TBARS) (Fig. 8A). While the TBARS assay is relatively insensitive and has a significant number of limitations for assessing endogenous oxidative stress, it was appropriate to assess the effect of MitoC on preventing lipid peroxidation in vitro induced by exogenous oxidants. This assay showed extensive lipid peroxidation that was blocked by low MitoC concentrations, (0.5 µM), while the TPMP cation alone was not protective (Fig. 8A). Mitochondrial energization with succinate enhanced protection, due to accumulation and recycling of MitoC (Fig. 8A). A dose-response curve showed that MitoC was protective against lipid peroxidation at several-hundred fold lower concentrations than ascorbate (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Prevention of mitochondrial oxidative damage by MitoC. (A) Effect of MitoC on mitochondrial lipid peroxidation assessed by TBARS. Mitochondria (2.5 mg protein/ml) were incubated with rotenone (4 µg/ml) with MitoC (5 µM or 0.5 µM) or TPMP (5 µM), in the presence (+) or absence (-) of 10 mM succinate. After 2 min preincubation H2O2 (100 µM) and FeCl2 (30 µM) were added and 5 min later TBARs were quantified. Data are means±SEM of three independent incubations. (B) Concentration-dependent effect of MitoC on mitochondrial lipid peroxidation assessed by TBARs formation. Mitochondria were incubated as in A with MitoC (0.01–5 µM) or ascorbate (5–2500 µM) and TBARS formation was quantified. (C) Time course of MitoPerox fluorescence. Mitochondria (0.5 mg protein/ml) were incubated±succinate (10 mM) in the presence of LAH (25 µM), 1 µM MitoPerox±5 µM MitoC,±5 µM ascorbic acid. (D) Effect of MitoC on aconitase inactivation by reverse electron transfer (RET). Mitochondria (2 mg protein/ml) were incubated with succinate (10 mM) for 7 min. Rotenone (4 μg/ml) was added to a control incubation to prevent RET. Test compounds were present at 5 μM. (E) Effect of MitoC on aconitase inactivation by paraquat (PQ). Mitochondria (2 mg protein/ml)±MitoC (5 μM) were incubated with succinate (10 mM) and PQ for 7 min and then analyzed for aconitase activity. Data are means±SEM of three independent incubations. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed Student's t-test (⁎P<0.05, ⁎⁎ P<0.001, ⁎⁎⁎ P<0.0001).

To further analyze the effect of MitoC on lipid peroxidation we used a mitochondria–targeted lipid-peroxidation probe, MitoPerOx [36] and initiated peroxidation with linoleic acid hydroperoxide (LAH), which increased MitoPerOx fluorescence (Fig. 8C). The increase in fluorescence was largely prevented by MitoC, but not by the same concentration of ascorbate (Fig. 8C). MitoC was only transiently protective against lipid peroxidation in de-energized mitochondria (Fig. 8C), presumably due to its lack of concentration and recycling within the matrix. As MitoC does not react with peroxides the protection is most likely due to its reduction of the oxygen and carbon centred radicals generated during lipid peroxidation. This reaction may be facilitated by MitoC adsorbing to the matrix-facing surface of the inner membrane, as occurs for MitoQ [31]. MitoC may also recycle the α-tocopheroxyl radical by shuttling electrons from the GSH and Trx systems, thereby facilitating the role of Vitamin E as a membrane-based antioxidant [13], [14].

To see if MitoC was also protective against oxidative damage in the matrix we investigated the superoxide-dependent inactivation of mitochondrial aconitase. Superoxide that evades MnSOD can inactivate aconitase rapidly (k ~107 M−1s−1). As ascorbate reacts relatively rapidly with superoxide (k ~3×105 M−1s−1[10]) the accumulation of MitoC within the matrix may protect aconitase by sequestering superoxide. To assess this we induced superoxide production by reverse electron transport (RET) from complex I, which lowered aconitase activity (Fig. 8D). MitoC decreased this damage, while ascorbate and the mitochondria-targeted antioxidants MitoQ and MitoTEMPOL did not (Fig. 8D). The redox cycler paraquat produces superoxide within mitochondria [37] and also led to aconitase inactivation that was decreased by MitoC (Fig. 8E). While aconitase protection by MitoC is likely to be largely due to superoxide sequestration, MitoC may also reduce ferric iron to the ferrous form (Fig. 6F), and thereby help reactivate aconitase by facilitating iron reinsertion, as happens for cytosolic aconitase [38], [39]. In summary, these findings show that MitoC is an effective mitochondria-targeted antioxidant due to its accumulation and recycling within mitochondria.

3. Conclusion

The targeting of antioxidants and bioactive molecules to mitochondria by conjugation to the lipophilic TPP cation is effective both as a therapeutic strategy and as a tool in the investigation of mitochondrial function. To date, these molecules have comprised a hydrophobic moiety conjugated to a TPP cation that drives their selective uptake into mitochondria. However, it was unknown if ionisable and polar bioactive compounds could be targeted to mitochondria. Here we have shown that TPP can be used to target ascorbate to mitochondria. That MitoC is accumulated, despite being present largely as a zwitterion, indicates that it is taken up as the protonated monocation, and uptake was enhanced by the pH gradient [19]. The uptake of MitoC by mitochondria required a long hydrophobic chain to counteract the polarity of the carbohydrate ascorbate. Therefore the TPP delivery system can be expanded to deliver polar and ionisable groups to mitochondria.

MitoC is a potent mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, several hundred-fold more potent in preventing mitochondrial oxidative damage than unmodified ascorbate. This was because it is accumulated several hundred-fold by mitochondria. The polarity of MitoC may enable it to act as an antioxidant in the aqueous matrix as well as an electron shuttle to the membrane. These unique aspects of its antioxidant action make MitoC a useful complement to more hydrophobic compounds such as MitoQ. MitoC expands the therapeutic and investigational uses of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants and will be a useful tool to explore the role of ascorbate within mitochondria.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK)MC-A070-5PS30.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.160.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy M.P. Mitochondrial thiols in antioxidant protection and redox signaling: distinct roles for glutathionylation and other thiol modifications. Antiox. Redox Signal. 2012;16:476–495. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R.A.J., Hartley R.C., Cochemé H.M., Murphy M.P. Mitochondrial pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;33:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelso G.F., Porteous C.M., Coulter C.V., Hughes G., Porteous W.K., Ledgerwood E.C., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Selective targeting of a redox-active ubiquinone to mitochondria within cells: antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:4588–4596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Animal and human studies with the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ. Annals N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1201:96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snow B.J., Rolfe F.L., Lockhart M.M., Frampton C.M., O'Sullivan J.D., Fung V., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P., Taylor K.M. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ as a disease-modifying therapy in Parkinson's disease. Movement Dis. 2010;25:1670–1674. doi: 10.1002/mds.23148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gane E.J., Weilert F., Orr D.W., Keogh G.F., Gibson M., Lockhart M.M., Frampton C.M., Taylor K.M., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant mitoquinone decreases liver damage in a phase II study of hepatitis C patients. Liver Int. 2010;30:1019–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith R.A.J., Hartley R.C., Murphy M.P. Mitochondria-targeted small molecule therapeutics and probes. Antiox. Redox Signal. 2011;15:3021–3038. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du J., Cullen J.J., Buettner G.R. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1826:443–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr A., Frei B. Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions? FASEB J. 1999;13:1007–1024. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuddihy S.L., Parker A., Harwood D.T., Vissers M.C., Winterbourn C.C. Ascorbate interacts with reduced glutathione to scavenge phenoxyl radicals in HL60 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;44:1637–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winkler B.S. Unequivocal evidence in support of the nonenzymatic redox coupling between glutathione/glutathione disulfide and ascorbic acid/dehydroascorbic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1117:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(92)90026-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Packer J.E., Slater T.F., Willson R.L. Direct observation of a free radical interaction between vitamin E and vitamin C. Nature. 1979;278:737–738. doi: 10.1038/278737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niki E. Role of vitamin E as a lipid-soluble peroxyl radical scavenger: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;66:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X., Cobb C.E., Hill K.E., Burk R.F., May J.M. Mitochondrial uptake and recycling of ascorbic acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;387:143–153. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munoz-Montesino C., Roa F.J., Pena E., Gonzalez M., Sotomayor K., Inostroza E., Munoz C.A., Gonzalez I., Maldonado M., Soliz C., Reyes A.M., Vera J.C., Rivas C.I. Mitochondrial ascorbic acid transport is mediated by a low-affinity form of the sodium-coupled ascorbic acid transporter-2. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2014;70:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee Y.C., Huang H.Y., Chang C.J., Cheng C.H., Chen Y.T. Mitochondrial GLUT10 facilitates dehydroascorbic acid import and protects cells against oxidative stress: mechanistic insight into arterial tortuosity syndrome. Hum. Mol. Gen. 2010;19:3721–3733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross M.F., Kelso G.F., Blaikie F.H., James A.M., Cochemé H.M., Filipovska A., Da Ros T., Hurd T.R., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Lipophilic triphenylphosphonium cations as tools in mitochondrial bioenergetics and free radical biology. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;70:222–230. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finichiu P.G., James A.M., Larsen L., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Mitochondrial accumulation of a lipophilic cation conjugated to an ionisable group depends on membrane potential, pH gradient and pKa: implications for the design of mitochondrial probes and therapies. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2013;45:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9493-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terajima T., Takai T., Nakamura H. Modified ion exchange resins with higher selectivity in bisphenol preparation. 2006 WO 2006003803 A1 20060112. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wimalasena K., Dharmasena S., Wimalasena D.S., Hughbanks-Wheaton D.K. Reduction of dopamine beta-monooxygenase. A unified model for apparent negative cooperativity and fumarate activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26032–26043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ju-Nam Y., Allen D.W., Gardiner P.H.E., Bricklebank N. ω-Thioacetylalkylphosphonium salts: precursors for the preparation of phosphonium-functionalised gold nanoparticles. J. Organometal. Chem. 2008;693:3504–3508. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowski T., Drescher S., Meister A., Hause G., Blume A., Dobner B. Synthesis of optically pure diglycerol tetra-ether model lipids with non-natural branching pattern. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011;29:5894–5904. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grotjahn D.B., Larsen C.R., Gustafson J.L., Nair R., Sharma A. Extensive isomerization of alkenes using a bifunctional catalyst: an alkene zipper. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9592–9593. doi: 10.1021/ja073457i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark T.D., Dugan E.C. Preparation of oligo(ethylene glycol)-terminated icosanedisulfides. Synthesis. 2006:1083–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asin-Cayuela J., Manas A.R., James A.M., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Fine-tuning the hydrophobicity of a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant. FEBS Letts. 2004;571:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. Reaction of linoleic acid hydroperoxide with thiobarbituric acid. J. Lipid Res. 1978;19:1053–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brand M.D. Measurement of mitochondrial protonmotive force. In: Brown G.C., Cooper C.E., editors. Bioenergetics-a practical approach. IRL; Oxford: 1995. pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beer S.M., Taylor E.R., Brown S.E., Dahm C.C., Costa N.J., Runswick M.J., Murphy M.P. Glutaredoxin 2 catalyzes the reversible oxidation and glutathionylation of mitochondrial membrane thiol proteins: implications for mitochondrial redox regulation and antioxidant defense. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47939–47951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurd T.R., Collins Y., Abakumova I., Chouchani E.T., Baranowski B., Fearnley I.M., Prime T.A., Murphy M.P., James A.M. Inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2 by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:35153–35160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James A.M., Cochemé H.M., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Interactions of mitochondria-targeted and untargeted ubiquinones with the mitochondrial respiratory chain and reactive oxygen species. Implications for the use of exogenous ubiquinones as therapies and experimental tools. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21295–21312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross M.F., Da Ros T., Blaikie F.H., Prime T.A., Porteous C.M., Severina I.I., Skulachev V.P., Kjaergaard H.G., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Accumulation of lipophilic dications by mitochondria and cells. Biochem. J. 2006;400:199–208. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lillig C.H., Berndt C., Holmgren A. Glutaredoxin systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1780:1304–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmgren A., Johansson C., Berndt C., Lonn M.E., Hudemann C., Lillig C.H. Thiol redox control via thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:1375–1377. doi: 10.1042/BST0331375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.May J.M., Mendiratta S., Hill K.E., Burk R.F. Reduction of dehydroascorbate to ascorbate by the selenoenzyme thioredoxin reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22607–22610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prime T.A., Forkink M., Logan A., Finichiu P.G., McLachlan J., Li Pun P.B., Koopman W.J., Larsen L., Latter M.J., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. A ratiometric fluorescent probe for assessing mitochondrial phospholipid peroxidation within living cells. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2012;53:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cochemé H.M., Murphy M.P. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1786–1798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toth I., Bridges K.R. Ascorbic acid enhances ferritin mRNA translation by an IRP/aconitase switch. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:19540–19544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toth I., Rogers J.T., McPhee J.A., Elliott S.M., Abramson S.L., Bridges K.R. Ascorbic acid enhances iron-induced ferritin translation in human leukemia and hepatoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:2846–2852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material