Abstract

Metabolomics is defined as the quantitative measurement of the dynamic multiparametric metabolic response of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli or genetic modification. It is an “omics” technique that is situated downstream of genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics. Metabolomics is recognized as a promising technique in the field of systems biology for the evaluation of global metabolic changes. During the last decade, metabolomics approaches have become widely used in the study of liver diseases for the detection of early biomarkers and altered metabolic pathways. It is a powerful technique to improve our pathophysiological knowledge of various liver diseases. It can be a useful tool to help clinicians in the diagnostic process especially to distinguish malignant and non-malignant liver disease as well as to determine the etiology or severity of the liver disease. It can also assess therapeutic response or predict drug induced liver injury. Nevertheless, the usefulness of metabolomics is often not understood by clinicians, especially the concept of metabolomics profiling or fingerprinting. In the present work, after a concise description of the different techniques and processes used in metabolomics, we will review the main research on this subject by focusing specifically on in vitro proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy based metabolomics approaches in human studies. We will first consider the clinical point of view enlighten physicians on this new approach and emphasis its future use in clinical “routine”.

Keywords: Metabolomics, In vitro nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, Liver diseases, Cirrhosis

Core tip: Metabolomics is a powerful technique to improve our pathophysiological knowledge of various liver diseases, to help clinicians in the diagnostic process as well as in the prognosis or therapeutic response assessment. Nevertheless, the usefulness of metabolomics is often not understood by clinicians. In the present work, after a concise description of the different techniques and processes used in metabolomics, we will review the main research on this subject by focusing specifically on proton nuclear magnetic resonance based metabolomics in human studies. Three major themes will be enlightened: acute liver disease, chronic liver disease and liver transplantation.

INTRODUCTION

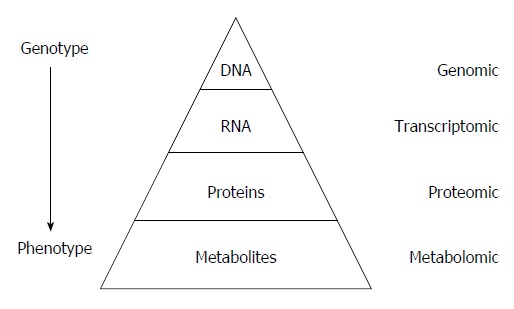

Metabolomics is an “omics” technique that is situated downstream of genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics (Figure 1)[1]. Metabolomics is the study (and by the way the monitoring) of metabolic changes in an integrated biological system related to (patho-) physiological stimuli or genetic modification, using multiparametric analyses.

Figure 1.

“Omic” techniques. Schematic representation in biological system: Each functional level from the DNA, RNAs, Proteins and metabolites who constitute respectively the genome, transcriptome, proteome and metabolome, have bidirectional flow of information and complex interactions together and with the environment (diseases, drug, lifestyle, genre, habit, diet, etc.). Those interactions produce the phenotype that represents the final output of the system measured in metabolomics.

The fundamental of metabolomics is that disease (or therapeutic response) can be reflected by changes in metabolite concentrations in biological fluids or tissues. This concept is not really new. More than 500 years ago, the “urine wheel” was published by Ullrich Pinder in his book (the Epiphanie Medicorum, 1506). The wheel described color, taste and smell of urine to help physicians in making-diagnoses. In other words, the phenotype of the urine was used to help the clinician. Now analytical tools to measure small-molecule metabolites called biomarkers have become tools in hospital laboratories to assist physicians when diagnosing disease.

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy and mass spectroscopy (MS) based metabolomics approaches are the two most applied experimental methods in this area[2]. They allow identifing and quantifing metabolites within a biological fluid (serum, plasma, urine, ascites, bile…) in a single experiment. Metabolites are small molecules (less than 1 kDa) that participate in general metabolic reactions or pathways in biofluid or tissue. The term metabolome, derived from the word genome, refers to the complete set of metabolites in a biofluid, cell, tissue or organism[3]. For example, the human serum metabolome is composed of around 4200 metabolites, half of which are phospholipids and over a thousand glycerolipids (triglycerides, diglycerides, and monoacylglycerols). Amino acids, peptides, carbohydrates, amines, and carboxylic acids are other metabolites being part of serum metabolome[4].

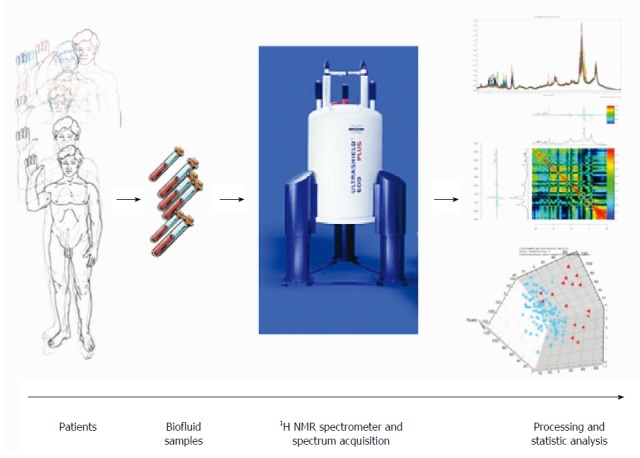

Data analysis in metabolomics and the process between, patients biofluid or tissue collection and the final interpretation have been well standardized[5]. The principal steps to achieve this approach are: collection of fluid or tissues, sample conservation, sample preparation before signal acquisition, signal acquisition in NMR (or MS) platform, data processing and analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic view of workflow for metabolomic studies: From bedside to bench. Proposed standards for metabolomic approach are presented in this schematic view. Clinical question, selection of the population, standardized biofluid collection and conservation, biofluid preparation and spectra acquisition, pre-processing to clean the data for data processing, pre-treatment (i.e., scaling, centering, etc.) to transform the clean data to make them ready for data processing, data analysis (multivariate analysis, unsupervised and supervised analysis), metabolite identification and interpretation.

Technically, each approach is grounded in different theoretical principles. MS spectroscopy is based on the separation of the metabolites using chemical and physical properties and NMR is based on the magnetic properties of some atoms. In MS spectroscopy, after specific preparation in function of the kind of metabolite analyzed (lipids or amino-acid or other type of metabolite), the sample is ionized and different metabolites are separated by their charges and mass.

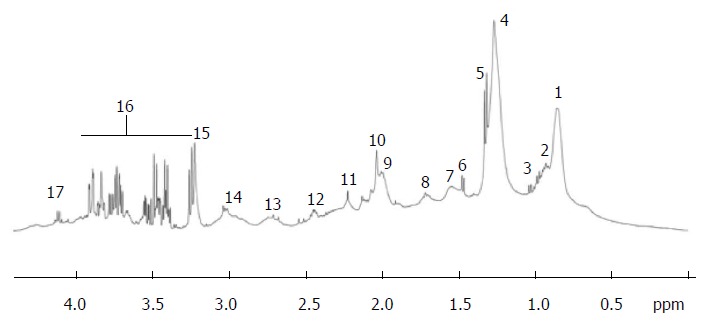

NMR spectroscopy is often easier to understand for the physician because using exactly the same principle than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that is largely used daily in medicine. The principle behind NMR is that many nuclei have a nuclear spin value (for example: hydrogen, 31phosphorus or 13carbon) and all nuclei are electrically charged. If an external magnetic field is applied, transitions are possible between the ground and excited spin states (i.e., energy transfert between the baseline to a higher energy level). The energy transfer takes place at a wavelength that corresponds to radio frequencies and when the spin returns to its base level, energy is emitted at the same frequency. The signal that matches this transfer is measured in many ways and processed in order to yield an NMR spectrum. Then instead to obtain an image like in MRI, in 1H NMR spectroscopy the signal is transformed in one or two dimensions spectra (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Typical proton nuclear magnetic resonance (500 MHz) spectra of the region between 0 and 6 ppm from cirrhotic patient. Region between 4.5 and 5.0 ppm corresponding to the water and urea was suppressed. Peak assignment: 1: Fatty acids (-CH2-CH2-CH2-CH3); 2: Isoleucine; 3: Valine; 4: Fatty acids (-CH2-CH2-CH2-); 5: Lactate; 6: Alanine; 7: Fatty acids (-CH2-CH2-CO-); 8: Fatty acids (-CH2-CH2-CH=); 9: Fatty acids (=CH-CH2-CH2-); 10: Acetyl signals from α1-acid glycoprotein; 11: Fatty acids (-CH2-CO-); 12: Glutamine; 13: Fatty acids (=CH-CH2-CH=); 14: Albumin lysyl; 15: Choline; 16: Glucose; 17: Lactate; 18: Fatty acids (-CH=CH-). Adapted from Nahon et al[29].

In 1H NMR spectroscopy, metabolites are identified by peaks shape, peaks multiplicity and peaks correlations. Large databases as the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) are available to find out all the metabolite characteristics[6,7].

Those techniques have advantages and disadvantages but are often complementary (Table 1).

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectroscopy

| NMR | MS | |

| Sensitivity (detection limit) | Usually micromolar (nanomolar with cryosonde) | Picomolar |

| Reproducibility | High | Low |

| Detected | Non targeted approach | Targeted approach |

| Metabolite | Detect metabolite Only if contain proton on the molecule | Need specific preparation to well detected some metabolites (Lipids…) |

| Metabolite identification | Easy, using 1D and/or 2D spectra and databases | More difficult, need sometime complementary analysis |

| Number of know identifiable metabolites | More than 200 | More than 4000 |

| Sample | Simple preparation (minimal add of D2O, Buffer and sometime reference) | Preparation more complex (protein extraction, etc.) |

| Non destructive method | Destructive method | |

| Need 400 μL (less than 10 μL with microprobe) | Need few microliters | |

| Type of sample | Liquid (urine, whole blood, serum, plasma, etc.) and intact tissue | Liquid |

| Cost of machine | Very high | High |

| Cost of sample analysis | Lower | Higher |

| Signal acquisition time | 5 to 15 min for 1D spectra | Around 10 min |

| More longer for 2D spectra (few hours) |

NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance; MS: Mass spectroscopy.

Basically, 1H NMR metabolomics approach has the advantage of efficiently obtaining information on large numbers of metabolites in biofluids in vitro as well as in various tissues ex vivo (using HR-MAS: high-resolution magic angle spinning) and in vivo (using Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging). 1H NMR is a highly reproducible, rapid and non-destructive technique. Analysis can be performed with a minimal of sample preparation. Its sensitivity is far lower (microgram vs picogram) than mass spectrometry but sufficient to detect most of changes in biological fluid. MS needs more sample preparation and is a destructive technique. Well-conducted reviews provide larges understanding details on the different platforms especially concerning the technical aspect, physical based-mechanism and analytical method use in metabolomics[1,3,8].

Thus these approaches offer high-throughput analyses at relatively low cost per sample. Multiparameter datasets contain huge quantity of information concerning metabolites in the form of complex spectrum data. Many computer-based processing and statistical tools have been developed to facilitate analysis and interpretation of the data. Statistical models applied to metabolomics data can determine biomarkers or metabolomics profiles[9]. They may help identify biomarkers or the metabolic profile that characterize a disease, and/or evaluate metabolic modifications after treatment has been initiated[3]. The metabolite analysis provides information on the “metabolic phenotype” of the patient in response to various endogenous or exogenous stimuli. Then that may contribute to a better understanding of pathophysiology, to aid diagnosis, in decision-making process in choosing therapy or predicting outcome of therapeutic intervention. In the other hand, in the near future, these tools permit us to give our patients a more personalized approach in medicine[10].

Metabolomics approach showed sometime better diagnosis performance than usual biomarkers. Nevertheless, at the beginning, metabolomics approach should be considered more than complementary tool, helping clinician to diagnose disease, evaluate disease stage or follow treatment that substitution technic.

This review focuses on the recent human metabolomics data in the field of liver disease and their complications using in vitro 1H NMR metabolomics approaches. MS based metabolomics approaches and in vivo MR studies are excluded from this review.

APPLICATIONS OF 1H NMR METABOLOMICS APPROACHES IN LIVER DISEASES

The liver is a major organ with several intensive metabolic activities. The metabolic activities are distributed in different zones of the liver parenchyma. Hepatocytes metabolism varies according to its position in the liver: for example, oxidative phosphorylation, glucose output, urea synthesis, and bile acid synthesis is higher in the periportal area, whereas glucose uptake, glutamine formation, and xenobiotic metabolism are greater in the perivenous area[11]. Acute, chronic, and acute-on-chronic conditions perturb regulation of liver metabolism. From this point of view, the blood or urine metabolome should represent the final outcome of liver cellular regulation at many different levels, and for this reason represent the phenotype of a disease or a therapeutic response.

We divided the following parts into three domains: acute liver disease, chronic liver disease and liver transplantation. Major studies and biomarkers examples for each part are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of metabolite changes involved in liver diseases in nuclear magnetic resonance based metabolomics approaches

| Metabolites | Variation | Model/pathology | Sample | Ref. |

| 2OH butyrate | - | HBV vs HEV | Plasma | [36] |

| 3OH butyrate | + | ximelagatran toxicity | Plasma | [37] |

| 3OH butyrate | + | Cirrhosis (HBV/alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| Acetate | + | acetaminophen toxicity | Urine | [14] |

| Acetate | + | HCC vs cirrhosis | Serum | [29] |

| Acetate | - | Cirrhosis severity | Serum | [20] |

| Acetoacetate | - | Cirrhosis and encephalopathy | Serum | [26] |

| Acetoacetate | + | Cirrhosis (HBV/alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| Acetoacetate | - | HBV vs alcohol cirrhosis | Serum | [24] |

| Acetoacetate | - | HBV vs control | Urine | [36] |

| Acetoacetate | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Acetone | - | HEV vs control | Plasma | [36] |

| Acetone | + | Cirrhosis (HBV/alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| Acetone | - | Decompensated vs compensated cirrhosis | Serum | [25] |

| acetone | - | HCC vs Cirrhosis vs controls | Urine | [31] |

| Acetone | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| bile acids | + | Cholangicarcinoma vs other causes | Bile | [38] |

| Bile acids | + | HCC vs adjacent tissue | Liver tissue | [39] |

| Carnitine | - | HBV vs control | Plasma | [36] |

| Citrate | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Choline | - | fibrosis vs cirrhosis | liver tissue | [21] |

| Choline | + | HCC vs adjacent tissue | liver tissue | [39] |

| Choline, P-choline | - | Cirrhosis severity | serum | [20] |

| Creatine | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Creatine | + | high grade HCC vs low grade HCC | Liver tissue | [39] |

| Dimethylamine | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Fatty acids | - | Biliary tract cancer | Bile | [33] |

| Fatty acids | - | Non fonctionnal vs fonctionnal graft after liver transplantation | Blood (extraction) | [34] |

| fatty acids | - | Cirrhosis and encephalopathy | Serum | [26] |

| fatty acids (HDL) | - | Cirrhosis severity | Serum | [20] |

| fatty acids (HDL) | - | HCC vs cirrhosis | Serum | [29] |

| Glutamine | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Glycerol | + | HEV vs control | Plasma | [36] |

| Glycerol | + | Cirrhosis and encephalopathy | Serum | [26] |

| GPC | - | mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| GPC | + | HCC vs adjacent tissue | Liver tissue | [39] |

| GPC/P-choline | - | Cirrhosis (HBV/alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| Histidine | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Isobutyrate | + | Cirrhosis (HBV/alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| Isobutyrate | + | HBV vs alcohol cirrhosis | Serum | [24] |

| LDL | - | Cirrhosis (HBV/alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| LDL | - | decompensated vs compensated cirrhosis | Serum | [25] |

| lipids | - | HCC vs adjacent tissue | Liver tissue | [39] |

| lipids | - | high grade HCC vs low grade HCC | Liver tissue | [39] |

| OH-butyrate | - | Cirrhosis severity | Serum | [20] |

| P-choline | + | Fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [21] |

| P-choline | - | Mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| P-choline | + | HCC vs adjacent tissue | Liver tissue | [39] |

| P-choline | + | Cirrhosis and encephalopathy | Serum | [26] |

| P-choline/GPC | - | High grade HCC vs low grade HCC | Liver tissue | [39] |

| Pdt-choline | + | Cholangicarcinoma vs non cancer | Bile | [38] |

| Pdt-choline | - | Mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| P-ethanolamine | + | HCC vs adjacent tissue | Liver tissue | [39] |

| P-ethanolamine | + | High grade HCC vs low grade HCC | Liver tissue | [39] |

| P-ethanolamine | + | Fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [21] |

| PUFA | - | Mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| Pyruvate | + | AIH vs healthy, PBC, OS and DILI | Plasma | [17] |

| Saturation index | + | Mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| Total lipids | +, - | Mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| Total choline/lipids | - | Mild vs moderate fibrosis vs cirrhosis | Liver tissue | [40] |

| Unsaturated FA | + | Fibrose vs cirrhose | Liver tissue | [21] |

| Unsaturated FA | + | Cirrhosis (HBV/Alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| VLDL | - | Cirrhosis (HBV/Alcohol) vs controls | Serum | [24] |

| VLDL | - | Decompensated vs compensated cirrhosis | Serum | [25] |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HBE: Hepatitis E virus; HBC: Hepatitis C virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; OS: Overleap syndrome; PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis; DILI: Drug induced liver injury; FA: Fatty acid; HDL: High density lipoproteins; LDL: Low density lipoproteins; VLDL: Very low density lipoproteins; P-choline: Phospho-choline; GPC: Glycerol-phospho-choline; P-ethanolamine: Phosphor-ethanolamine; PUFA: Polyunsaturated fatty acids; Pdt-choline: Phosphatidylcholine.

Acute liver disease

Drug induced liver injury: Metabolomics have been used since decennia in toxicological studies principally in animal models[12]. Some recent studies have shown that metabolomics can be a powerful tool in human toxicology. Clayton et al[13] have used NMR metabolomics to study the secondary metabolism of acetaminophen in urine. The goal was to identify urine biomarkers that might be predictive of the manner in which that individual metabolizes the acetaminophen. In this study, results suggested a mechanism whereby p-cresol and acetaminophen would compete for sulfation. Then higher p-cresol levels would lead to lower levels of sulfated acetaminophen and increase toxicity. More interestingly metabolome analysis have been in evidence the interplay between gut bacteria and secondary drug metabolism because p-cresol is a product of bacterial metabolism of tyrosine in the gut. Winnike et al[14] used a pharmaco-metabolomics approach to predict acetaminophen induced liver injury with a therapeutic dose (4 g per day for 7 d). In human healthy volunteers and earlier after the beginning of the treatment, they were able to identify patterns of urinary metabolites that distinguished subjects susceptible to acetaminophen-hepatotoxicity from those who were not susceptible.

Those examples represent a major advance in personalized medicine. A NMR based metabolomics approach could be a practical method for identifying susceptible patients shortly after starting drug treatment and with high risk of developing DILI.

Liver injury and liver failure: Acute hepatic liver failure is a very severe condition with a high risk of mortality. Predictability of survival without liver transplantation is often difficult. Using 1H NMR on serum and urine, Saxena et al[15] has shown the potential to predict an unfavorable outcome from a metabolomic profile-evaluation in patients with fulminant hepatic failure. In this study, metabolomics profiles of patients with Fulminant Hepatic failure and favorable (n = 20) or unfavorable (n = 10) outcomes were compared. The results of this pilot study showed that one single biomarker (Glutamine) could permit to predict unfavorable outcome with a high sensitivity.

In another area of acute liver injury, Ranjan et al[16] examined serum in patients of liver injury to explore the possible clinical application of new metabolites as a biomarker to detect traumatic liver damage in blunt abdominal trauma. In this study, 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed only two amino acids, phenylalanine and tyrosine, in the sera of the subjects with liver injury, irrespective of the extent and type of injury gauged by radiology or laparotomy. The author concluded that these biomarkers detected by NMR spectroscopy could get a relevant clinical importance in establishing liver injury in patients with blunt abdominal trauma.

AutoImmune hepatitis: Diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is often difficult because of lack of specificity of biological and clinical signs. Moreover, diagnosis of AIH might be confounded with other acute liver conditions like DILI or primary biliary cirrhosis or overload from other diseases. Wang et al[17] assessed the utility of metabolomics in the diagnosis of the disease. Plasma metabolomics profiles of patients with AIH, PBC, DILI, PBC and healthy subjects were compared. Nine biomarkers showed great sensitivity in discriminating AIH from other disease were identified. The utility for the diagnosis of the biomarker panel was assessed and they achieved good sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing AIH from other diseases.

Chronic liver disease

Chronic viral hepatitis: Different viruses cause hepatitis infection. Hepatitis C virus is one of the most important and has infected about 150 million people worldwide[18]. Expensive biological methods to diagnosis HVC infection are problematic, especially in developing countries.

Several studies using metabolomics approaches in the field of viral hepatitis have been done. One of the most relevant is the study ran by Godoy et al[19]. In a metabolomics model based on 1H NMR spectra of urine they discriminated patients with HCV infection with high sensitivity (94%), specificity (97%) and accuracy (95%). These findings reveal the potential of metabolomics as a low cost, noninvasive diagnosis of HCV related hepatitis using urine samples.

Assessment of cirrhosis and its complications: Studies have shown a close relationship between metabolic abnormalities and the severity of the disease in sera and tissues[20-23]. In those studies, a metabolomics approach was a powerful tool in assessing the severity of chronic liver failure in alcohol-induced cirrhosis within a cohort of patients without acute decompensation. For instance, in our previous study, the severity of chronic liver failure was evaluated using the MELD score, and correlated well with impairment of lipid, glucose, and amino acid metabolism[20]. Other studies show that metabolomics can fingerprint the differences between compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, and between cirrhosis caused by alcohol or viruses[24,25].

Assessments of complication in patients with chronic liver disease, especially with cirrhosis, were performed using metabolomics approaches.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a well-known complication of liver cirrhosis. Its diagnosis is currently performed at the bedside using clinical examination. Unfortunately low grade or “sub-clinical” HE (also called minimal hepatic encephalopathy) is more difficult to diagnose and request using more complex psychometric tests that are time consuming and not realized in routine. In this case, biomarkers could be easier to use and helpful. Jiménez et al[26] have shown that using 1H-NMR to assess the metabolomics of sera from patients with cirrhosis could discriminate between patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy and those with no encephalopathy.

Recently, we described a serum metabolite fingerprint for acute-on-chronic liver failure, obtained with 1H-NMR[27]. The hypothesis in this study was that cirrhotic patients with acute event (acute-on-chronic liver failure or ACLF group) have had a specific metabolic response as compared to cirrhotic patients with stable cirrhosis (chronic liver failure or CLF group). Both groups were distinguished using multivariable statistical methods and specific metabolomics fingerprint of ACLF patients in intensive care unit was identified. Several metabolites were identified and reflected major change in liver function such as energy metabolism, urea metabolism or amino-acid metabolism but also major extra-liver function change such as renal impairment or related to inflammation and/or necrosis.

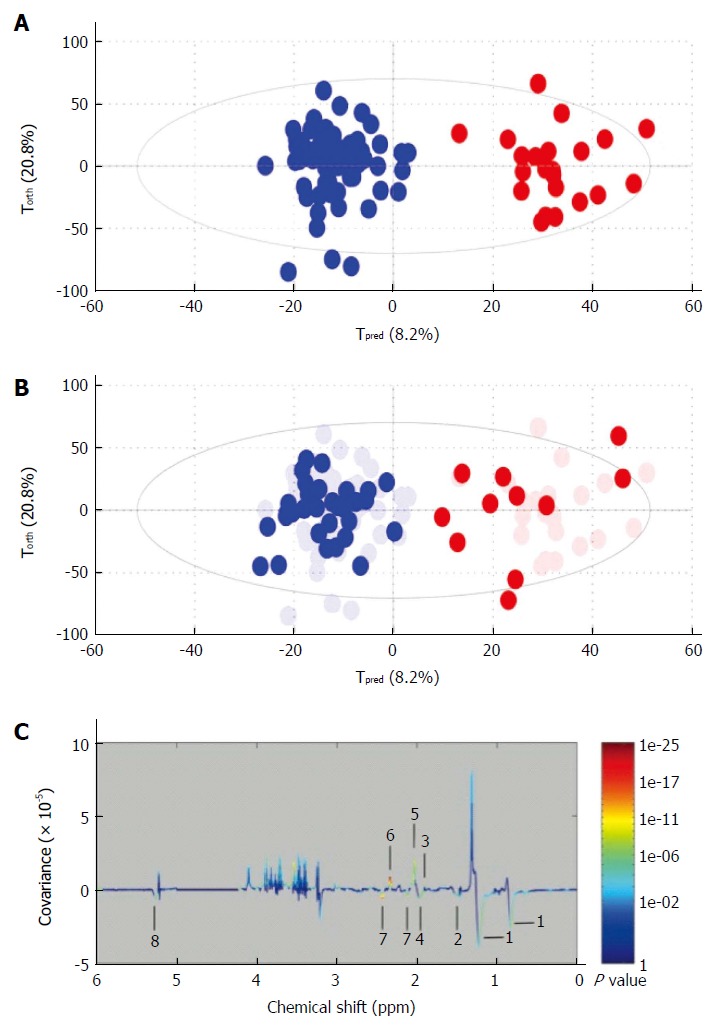

Liver cancer: Recent studies have attempted to describe the metabolic phenotype of liver cancer in heterogeneous populations of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using 1H NMR. This has led to the identification of various metabolically impaired pathways in serum and urine[28-31]. Goa et al[28] have shown that metabolite profiles obtained from 1H NMR-based metabolomics analysis of blood serum may be different in healthy volunteers compared to patients with liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Major changes to metabolites within the sera include lipids, ketone bodies, and amino-acid metabolism. Soper et al[32] have performed an in vitro 1H NMR spectroscopy study to characterize liver biopsy samples into normal, cirrhotic or hepatocellular carcinoma on the basis of a computer-based statistical classification strategy with changes in lipids, choline and creatine identified. Ninety-eight percent of hepatocellular carcinomas in this series were distinguished from non-malignant tissue on the basis of reduced lipid and increased choline content. We used this approach to assesse the metabolomic profiles of serum from alcoholic cirrhotic patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma[29]. This study included 154 consecutive patients with compensated biopsy-proven cirrhosis. Among these, 93 had cirrhosis without HCC, 28 had biopsy-proven HCC eligible for curative treatment (“small” HCC) and 33 had HCC outside the curative treatment criteria (“large” HCC). The first step in this study was to create a diagnostic model with “large” HCC population and validate it (Figure 4A and B). In this model, discriminant metabolites that increased with large HCC were, glutamate, acetate and N-acetyl glycoproteins, whereas metabolites that correlated with cirrhosis were lipids and glutamine (Figure 4C). The second step was to assess the diagnostic performance of the model using the “small HCC” population. Unfortunately projection of small HCC samples into the first model showed a heterogeneous distribution between large HCC and cirrhotic samples. Nevertheless, small HCC patients with metabolomic profiles similar to those of large HCC group had higher incidences of recurrence or death during follow-up (63% vs 47%). Serum NMR-based metabolomics identified metabolic fingerprints that could be specific to large HCC in cirrhotic livers. From a metabolomic standpoint, some patients with small HCC, who are eligible for curative treatments, seem to behave as patients with advanced cancerous disease. This finding indicates the usefulness of the monitoring by this approach during the follow-up of those patients before and after treatment.

Figure 4.

Example of metabolomic study using a training and test set to validate the model. A: Creation of the model. On this Figure called score plot, each point represented the projection of an NMR spectrum (and thus one patient is sample) on both axes of the model. On this score plot, each dot corresponds to a spectrum colored according to the absence (blue) or the presence (red) of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The constructed model provides a good distinction between the spectrum of cirrhotic patients without HCC and those with HCC; B: Validation of the model. Each new spectrum was projected in the score plot using the previously constructed model to enable prediction of the presence or absence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Each dot corresponds to a spectrum coloured depending on the absence (blue) or presence (red) of HCC; C: Discriminant metabolites. On this Figure called loading plot, variations of bucket intensities are represented using a line plot between 0 to 6 ppm. Positive signals correspond to the metabolites present at increased concentrations in patients with large HCC. Conversely, negative signals correspond to the metabolites present at increased concentrations in patients without HCC. 1: HDL; 2: Fatty acids; 3: Acetate; 4: Fatty acids; 5: N-acetyl-glycoprotein; 6: Glutamate; 7: Glutamine; 8: Fatty acids. Adapted from Nahon et al[29].

Biliary tract cancer is an uncommon type of liver cancer with high mortality and which is difficult to diagnosis. Wen et al[33] used metabolomics profile of bile to distinguish patients with biliary cancer from patients with benign biliary duct diseases. This approach provides a good performance to discriminate cancer from benign diseases. Moreover, metabolomics approach has shown higher diagnostic performance (sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 81%) than conventional tests (CA19-9; CEA and bile cytology).

Liver transplantation

Clinical course after liver transplantation is sometimes chaotic and life threatening Unfortunately, bad outcomes are unpredictable, especially immediately after the transplant. One of the major concerns for the transplant team immediately after the surgery is to know whether the graft works. Failure of graft function remains an important cause of mortality. Some serial reports using metabolomics approaches have shown interesting results concerning the follow-up of patients. Serkova et al[34] described the blood metabolomics profile, which permits early detection of graft failure. In this case report, they were able to identify several metabolites in case of graft failure using sequential approach with multiple samples in the same patient: lactate, uric acid, glutamine, methionine increase and total fatty acids, citrate decrease. Thus, they have shown that metabolomics profiling can be a additional tool in clinical decision making. Unfortunately, validation on this interesting work is not available.

To assess the quality of the liver before transplantation, Melendez et al[35] analyzed metabolomic profiles of hepatic bile in vitro 1H NMR spectroscopy. They included bile samples from donors and recipients. The main result showed a greater phosphatidylcholine signal in bile from steatotic graft compared with normal grafts.

CURRENT LIMITATION OF METABOLOMICS AND FUTURE CLINICAL APPLICATION

In this review we have highlighted studies that have advanced our understanding of various liver diseases. The examples above demonstrate that the integration of metabolomics approaches into basic and biomedical research is already improving our understanding of biological mechanism, with important applications in the study of disease and/or therapeutic response. Technological advances have brought metabolomics to the point where these techniques can find general application in medicine.

However, there are several challenges to be overcome before metabolomics approaches can become a valuable clinical tool. It will be necessary to translate the technic in hospital lab, improve, simplify and automatized bioinformatics strategies, automatic recon of biomarker or metabolomics profile, validated the results in large prospective observational and interventional studies with meaningful clinical-end point.

Only after that and probably in a near future, results from metabolomics approach (with analysis and interpretation) will be available to the clinician in less than 1 d.

Metabolomics profiling could be useful in personalized medicine for diagnosis, prognosis and to follow patients-response before and after treatment. Metabolomics has the potential of providing new criteria to risk-stratify patients and develop novel approaches for individualized treatment.

CONCLUSION

Metabolomics is a powerful method that can be used to quantitatively assess the differences in metabolite abundance or to determine metabolic fingerprint discriminating different disease states, the severity of disease extension, drug treatment metabolic impairment or pathophysiological mechanism investigation. The ability to perform such studies in a large range of biological samples, especially urine samples, which are easy to collect and non-invasive, makes it an attractive platform for translation to clinical use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. Virginia Eskridge (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) for her invaluable assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest associated with any of the senior author or other coauthors contributed their efforts in this manuscript.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 31, 2015

First decision: July 14, 2015

Article in press: December 1, 2015

P- Reviewer: Marchesini G S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Lindon JC, Nicholson JK. Spectroscopic and statistical techniques for information recovery in metabonomics and metabolomics. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2008;1:45–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernie AR, Trethewey RN, Krotzky AJ, Willmitzer L. Metabolite profiling: from diagnostics to systems biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nrm1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn WB, Broadhurst DI, Atherton HJ, Goodacre R, Griffin JL. Systems level studies of mammalian metabolomes: the roles of mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:387–426. doi: 10.1039/b906712b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psychogios N, Hau DD, Peng J, Guo AC, Mandal R, Bouatra S, Sinelnikov I, Krishnamurthy R, Eisner R, Gautam B, et al. The human serum metabolome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodacre R, Broadhurst D, Smilde AK, Kristal BS, Baker D, Beger RD, Bessant C, Connor S, Capuani G, Craig A, et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for data analysis in metabolomics. Metabolomics. 2007:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Human Metabolome Database. Available from: http://www.hmdb.ca/

- 7.Wishart DS, Tzur D, Knox C, Eisner R, Guo AC, Young N, Cheng D, Jewell K, Arndt D, Sawhney S, et al. HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D521–D526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trygg J, Holmes E, Lundstedt T. Chemometrics in metabonomics. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:469–479. doi: 10.1021/pr060594q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn WB, Bailey NJ, Johnson HE. Measuring the metabolome: current analytical technologies. Analyst. 2005;130:606–625. doi: 10.1039/b418288j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes E, Wilson ID, Nicholson JK. Metabolic phenotyping in health and disease. Cell. 2008;134:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jungermann K, Kietzmann T. Oxygen: modulator of metabolic zonation and disease of the liver. Hepatology. 2000;31:255–260. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindon JC, Keun HC, Ebbels TM, Pearce JM, Holmes E, Nicholson JK. The Consortium for Metabonomic Toxicology (COMET): aims, activities and achievements. Pharmacogenomics. 2005;6:691–699. doi: 10.2217/14622416.6.7.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clayton TA, Baker D, Lindon JC, Everett JR, Nicholson JK. Pharmacometabonomic identification of a significant host-microbiome metabolic interaction affecting human drug metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14728–14733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904489106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winnike JH, Li Z, Wright FA, Macdonald JM, O’Connell TM, Watkins PB. Use of pharmaco-metabonomics for early prediction of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:45–51. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxena V, Gupta A, Nagana Gowda GA, Saxena R, Yachha SK, Khetrapal CL. 1H NMR spectroscopy for the prediction of therapeutic outcome in patients with fulminant hepatic failure. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:521–526. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranjan P, Gupta A, Kumar S, Gowda GA, Ranjan A, Sonker AA, Chandra A. Detection of new amino acid markers of liver trauma by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Liver Int. 2006;26:703–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JB, Pu SB, Sun Y, Li ZF, Niu M, Yan XZ, Zhao YL, Wang LF, Qin XM, Ma ZJ, et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Autoimmune Hepatitis: The Diagnostic Utility of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J Proteome Res. 2014:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1021/pr500462f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godoy MM, Lopes EP, Silva RO, Hallwass F, Koury LC, Moura IM, Gonçalves SM, Simas AM. Hepatitis C virus infection diagnosis using metabonomics. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:854–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amathieu R, Nahon P, Triba M, Bouchemal N, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M, Dhonneur G, Le Moyec L. Metabolomic approach by 1H NMR spectroscopy of serum for the assessment of chronic liver failure in patients with cirrhosis. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3239–3245. doi: 10.1021/pr200265z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez-Granados B, Monleón D, Martínez-Bisbal MC, Rodrigo JM, del Olmo J, Lluch P, Ferrández A, Martí-Bonmatí L, Celda B. Metabolite identification in human liver needle biopsies by high-resolution magic angle spinning 1H NMR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:90–100. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-Granados B, Morales JM, Rodrigo JM, Del Olmo J, Serra MA, Ferrández A, Celda B, Monleón D. Metabolic profile of chronic liver disease by NMR spectroscopy of human biopsies. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:111–117. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2010.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu K, Sheng G, Sheng J, Chen Y, Xu W, Liu X, Cao H, Qu H, Cheng Y, Li L. A metabonomic investigation on the biochemical perturbation in liver failure patients caused by hepatitis B virus. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2413–2419. doi: 10.1021/pr060591d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi S, Tu Z, Ouyang X, Wang L, Peng W, Cai A, Dai Y. Comparison of the metabolic profiling of hepatitis B virus-infected cirrhosis and alcoholic cirrhosis patients by using (1) H NMR-based metabonomics. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:677–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi SW, Tu ZG, Peng WJ, Wang LX, Ou-Yang X, Cai AJ, Dai Y. ¹H NMR-based serum metabolic profiling in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:285–290. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i3.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiménez B, Montoliu C, MacIntyre DA, Serra MA, Wassel A, Jover M, Romero-Gomez M, Rodrigo JM, Pineda-Lucena A, Felipo V. Serum metabolic signature of minimal hepatic encephalopathy by (1)H-nuclear magnetic resonance. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:5180–5187. doi: 10.1021/pr100486e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amathieu R, Triba MN, Nahon P, Bouchemal N, Kamoun W, Haouache H, Trinchet JC, Savarin P, Le Moyec L, Dhonneur G. Serum 1H-NMR metabolomic fingerprints of acute-on-chronic liver failure in intensive care unit patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao H, Lu Q, Liu X, Cong H, Zhao L, Wang H, Lin D. Application of 1H NMR-based metabonomics in the study of metabolic profiling of human hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:782–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nahon P, Amathieu R, Triba MN, Bouchemal N, Nault JC, Ziol M, Seror O, Dhonneur G, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M, et al. Identification of serum proton NMR metabolomic fingerprints associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6714–6722. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shariff MI, Gomaa AI, Cox IJ, Patel M, Williams HR, Crossey MM, Thillainayagam AV, Thomas HC, Waked I, Khan SA, et al. Urinary metabolic biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in an Egyptian population: a validation study. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1828–1836. doi: 10.1021/pr101096f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shariff MI, Ladep NG, Cox IJ, Williams HR, Okeke E, Malu A, Thillainayagam AV, Crossey MM, Khan SA, Thomas HC, et al. Characterization of urinary biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma using magnetic resonance spectroscopy in a Nigerian population. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1096–1103. doi: 10.1021/pr901058t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soper R, Himmelreich U, Painter D, Somorjai RL, Lean CL, Dolenko B, Mountford CE, Russell P. Pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma and its precursors using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and a statistical classification strategy. Pathology. 2002;34:417–422. doi: 10.1080/0031302021000009324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wen H, Yoo SS, Kang J, Kim HG, Park JS, Jeong S, Lee JI, Kwon HN, Kang S, Lee DH, et al. A new NMR-based metabolomics approach for the diagnosis of biliary tract cancer. J Hepatol. 2010;52:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serkova NJ, Zhang Y, Coatney JL, Hunter L, Wachs ME, Niemann CU, Mandell MS. Early detection of graft failure using the blood metabolic profile of a liver recipient. Transplantation. 2007;83:517–521. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000251649.01148.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melendez HV, Ahmadi D, Parkes HG, Rela M, Murphy G, Heaton N. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of hepatic bile from donors and recipients in human liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:855–860. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200109150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munshi SU, Taneja S, Bhavesh NS, Shastri J, Aggarwal R, Jameel S. Metabonomic analysis of hepatitis E patients shows deregulated metabolic cycles and abnormalities in amino acid metabolism. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e591–e602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson U, Lindberg J, Wang S, Balasubramanian R, Marcusson-Ståhl M, Hannula M, Zeng C, Juhasz PJ, Kolmert J, Bäckström J, et al. A systems biology approach to understanding elevated serum alanine transaminase levels in a clinical trial with ximelagatran. Biomarkers. 2009;14:572–586. doi: 10.3109/13547500903261354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharif AW, Williams HR, Lampejo T, Khan SA, Bansi DS, Westaby D, Thillainayagam AV, Thomas HC, Cox IJ, Taylor-Robinson SD. Metabolic profiling of bile in cholangiocarcinoma using in vitro magnetic resonance spectroscopy. HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Li C, Nie X, Feng X, Chen W, Yue Y, Tang H, Deng F. Metabonomic studies of human hepatocellular carcinoma using high-resolution magic-angle spinning 1H NMR spectroscopy in conjunction with multivariate data analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2605–2614. doi: 10.1021/pr070063h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cobbold JF, Patel JH, Goldin RD, North BV, Crossey MM, Fitzpatrick J, Wylezinska M, Thomas HC, Cox IJ, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatic lipid profiling in chronic hepatitis C: an in vitro and in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Hepatol. 2010;52:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]