Summary

Background

DNA profiling with sets of highly polymorphic autosomal short tandem repeat (STR) markers has been applied in various aspects of human identification in forensic casework for nearly 20 years. However, in some cases of complex kinship investigation, the information provided by the conventionally used STR markers is not enough, often resulting in low likelihood ratio (LR) calculations. In these cases, it becomes necessary to increment the number of loci under analysis to reach adequate LRs. Recently, it has been proposed that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) could be used as a supportive tool to STR typing, eventually even replacing the methods/markers now employed.

Methods

In this work, we describe the results obtained in 7 revised complex paternity cases when applying a battery of STRs, as well as 52 human identification SNPs (SNPforID 52plex identification panel) using a SNaPshot methodology followed by capillary electrophoresis.

Results

Our results show that the analysis of SNPs, as complement to STR typing in forensic casework applications, would at least increase by a factor of 4 total PI values and correspondent Essen-Möller's W value.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that SNP genotyping could be a key complement to STR information in challenging casework of disputed paternity, such as close relative individualization or complex pedigrees subject to endogamous relations.

Keywords: Forensic genetics, Paternity testing, STRs, SNP markers

Introduction

In forensic genetics, DNA samples are analyzed through the comparison of a combination of variants from a particular group of polymorphisms, resulting in a highly unlikely probability of being reproduced in a second individual within the population. In fact, although more than 99% of the genome is invariable across the human population, polymorphic variations in DNA sequence can be used to both differentiate and correlate individuals. This DNA feature allows the resolution of many problems related with paternity testing and identification cases, including disaster victim identification (DVI). Moreover, it can be used to solve some criminal cases.

Short tandem repeats (STRs) have been the first-choice genetic markers of forensic scientists all over the world, since their use enables a satisfactory answer for almost all the requested cases, mainly due to their high degree of polymorphism and consequent discrimination power. Lately, however, another type of genetic markers called SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms), which consists in DNA sequence variations that results from single base changes in the genome sequence, has been considered [1,2] as additional informative markers, providing reliable likelihood ratios (LRs). Some reports go even further, considering that SNPs will replace STRs in forensic investigation [3]. In spite of almost all SNPs are bi-allelic, and consequently less polymorphic than multi-allelic STRs, they have several known advantages over STRs: SNPs are more stable genetic markers, with low mutation rates and so less likely changes over generations which is crucial concerning paternity cases. They also will probably allow a cheaper, easier and faster analysis and demand a much lower DNA consumption due to the high degree of multiplexing and automation of the genotyping methodologies [4,5]. Moreover, as single base markers, they can be typed with extremely short amplicons (around 50-90 bp) and since the typing reaction is independent from PCR amplification, a large number of markers can be amplified with similar amplicon lengths without any effect over genotyping [3]. This last property becomes critical when dealing with degraded DNA samples which display highly fragmented DNA. However, SNP analysis also presents some limitations. In fact, using statistic simulations to compare STRs and SNPs effectiveness in kinship studies, it has been reported that the possibility of inconclusive results is much higher when using only SNPs [2,6]. Furthermore, these authors discuss the validity of using exclusively SNP polymorphisms in routine paternity investigations. It is generally accepted that SNPs are individually less informative than STRs; however, their simplicity allows a multiplexing level so high that a single SNP typing multiplex could pile up a number of markers large enough to compensate this limitation [7].

In this work we present some paternity testing results, using conventional STR markers and the 52 SNP multiplex reported by the SNPforID consortium, that was locally validated using the SNaPshot® reaction mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) and capillary electrophoresis.

Material and Methods

Samples and Pedigree Description

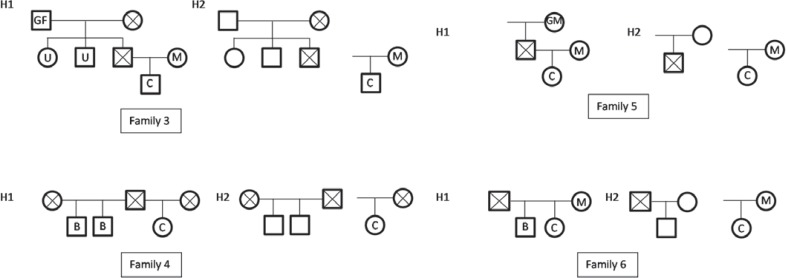

The samples were selected from 7 complex families that were already typed using conventional STR markers included in the Identifiler (Applied Biosystems) and in the PowerPlex 16 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) kits. The first three reported families concerned trios that had shown incompatibilities in one or two STR, suspected to be single step mutations (Family 1(F1), Family 2 (F2) and Family 7 (F7)), leading to reduced paternity indexes. In the other studied families instead of the alleged father we had other relatives from the paternal line: the alleged paternal grandfather and alleged uncle (Family 3 (F3)), two confirmed sons of the alleged father from a different mother (Family 4 (F4)), the alleged paternal grandmother (Family 5 (F5)) and a single confirmed son of the alleged father (Family 6 (F6)) (fig. 1). All these families were analyzed after typing with all markers included in the above mentioned commercial kits, totalizing 17 STRs.

Fig. 1.

Pedigrees of complex studied families: family 3, 4, 5, and 6.

DNA Extraction and Quantification

DNA was extracted using a slightly modified version of the Chelex extraction method [8]. Quantification was achieved by real-time PCR using the Quantifiler™ Human DNA Quantification Kit (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI PRISM® 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems).

PCR and Genotyping

A total of 52 autosomal SNPs were amplified by PCR in 12.5 µl reactions containing DNA ranging from 0.40 to 3 ng. The PCR procedures were performed as previously described [7]. Two single base extension (SBE) reactions were performed as previously described with slight modifications [7]: 2.5 µl SNaPshot reaction mix (Applied Biosystems), 1.5 µl SBE primer mix (0.01-0.27 µmol/l) and 2 µl of purified PCR product (with exonuclease I / shrimp alkaline phosphatase (ExoI-SAP)), 6 µl in total. Excess nucleotides were then removed by the addition of 1 µl SAP (1 U/µl) to the SBE mix. SBE products separation was performed by capillary electrophoresis, using an ABI Prism 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosciences), with 36 cm capillary arrays and POP-4 polymer (Applied Biosystems). Analysis was made using GeneMapper ID-X. Allele calls were made manually.

Statistical Analysis

After applying the SNPforID 52plex assay, calculations of paternity indexes (PI) were made using the software Familias [9] considering the information of STRs and of the 52 SNPs as stand-alone assays. The two assays were joined on a single genetic profile (table 1), using the previously published frequencies for those markers in a population sample of the North of Portugal [10] and assuming that all markers are independent.

Table 1.

Complex studied families: comparison of the calculated PI values using STR, SNPs, or a combined STR/SNP

| Family | PI (STRs) | W | PI (SNPs) | Total PI (STRs + SNPs) | Total W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 2,198.0 | 0.9995 | 1.29 × 102 | 2.83 × 105 | 0.9999929475 | 1 Mut D2S1338 |

| F2 | 2,955.0 | 0.9996 | 1.18 × 101 | 3.49 × 104 | 0.9999713948 | 2 Mut FGA and SE33 |

| F3 | 1,195.0 | 0.9992 | 4.12 | 4.92 × 103 | 0.9997969296 | GF + 2U+ C + M |

| F4 | 241.0 | 0.9959 | 7.31 | 1.75 × 103 | 0.9994319150 | 2 S (M1) + C (M2) |

| F5 | 1553.0 | 0.9994 | 9.43 × 102 | 1.46 × 106 | 0.9999993171 | GM + C + M |

| F6 | 3,865.0 | 0.9997 | 1.76 × 101 | 6.81 × 104 | 0.9999853163 | Brother + C +M |

| F7 | 6,133.0 | 0.9998 | 9.71 × 105 | 5.95 × 109 | 0.9999999998 | 1Mut D16S539 |

PI = Paternity index; W = Essen-Möller's probability value; GF = alleged paternal grandfather; U = alleged paternal uncle; C = child; M = mother; S = son of the alleged father; GM = alleged paternal grandmother; Mut = inconsistency in STR transmission.

Three of the studied cases involved incompatibilities, two (F1, F7) with one suspected single step mutation and the other one (F2) with two suspected single step mutations. In Familias software it is possible to take the mutation rates (mr) into consideration for those loci in order to obtain a value of probability for the alleged kinship relation. In the case of STRs we have inserted mr values from the STRbase with different values according to the marker with the observed incompatibility. The STRbase website lists a wide range of observed STR mutation rates(www.cstl.nist.gov/biotech/strbase/mutation.htm) based on data from the most extensive recent AABB survey on typing trios with standard STRs (www.aabb.org/sa/facilities/Documents/ptannrpt03.pdf). A universal mutation rate of mr = 2.5 × 10-8 was used for all SNPs [11,12]. Silent alleles were also assumed. The silent allele frequencies were calculated according the equation 1 / (n + 1), were n corresponds to the total number of observed alleles.

Quality Control

The recommendations of the International Society of Forensic Genetics (ISFG) on the analysis of DNA polymorphisms were strictly followed which included the use of recommended nomenclature and guidelines regarding quality control and statistical calculations [13]. The SNPforID 52plex assay was validated locally and through inter-laboratory collaborative exercises, prior to sample typing, promoted by the Spanish and Portuguese Working Group from ISFG (GHEP-ISFG group).

Results and Discussion

In table 1 the studied families and the respective PI calculations with STRs, SNPs, and both markers are resumed. Concerning genetic data interpretation, STR PI results range from 241 to 6,133, SNP PI results range from 4 to 971,396, whereas using the combined STR/SNP PI results range from 1,759 to 5,957,575,011. Our results are in agreement with previous reports from other authors stating that in most families the PI value obtained analyzing just SNPs was lower than with STRs analysis [2]. These authors propose that the use of SNPs, in some cases, will lead to a PI lower than the one obtained with STR information, returning an inconclusive statistic calculation [2]. However, our results show that, by gathering the information of these two types of markers together, it was possible to achieve an increased PI in all revised cases. In 4 out of the 7 cases, SNPs were not very informative, with PI < 20. This was expected, since these are the most difficult cases that can emerge from the routine work in which it is very common to lack sufficient information for a kinship investigation, since in one case there are two incompatibilities in STR analysis (F2) and in the others we dispose of far relatives of the child, as is the case of grandparents, uncles or brothers (F3, F4, and F6). Inview of these data it is demonstrated that studying SNPs as a complement to STRs resulted in an at least fourfold increased total PI values, while in the remaining cases the PI improvement is several magnitude orders greater. Special attention is given to the case F7 displaying a mutation on D16S539 across generations in which the application of SNP typing and ignoring STR data increase the PI by two magnitude orders. These results may be explained by the fact that the applied SNP typing multiplex, SNPforID 52plex, in European populations provides a higher statistical power than the 15 human identity STRs contained on the employed amplification kit [7]. Furthermore, since the mutation rate of SNPs is on average five magnitude orders lower than that of STRs, it is highly unlikely that any parent-to-child mutation will be spotted. Moreover, the combined STR/SNP increased PI results, leading to a strongly supported hypothesis of paternity and an accurate conclusion. Similar results when applied to complex casework resolution have been obtained with SNP typing by other authors [6,13,14,15] – hardly a surprise, since this methodology accomplishes the single-tube-reaction study of a great number of markers. Additionally, these markers show an extremely low mutation rate, and those on the SNPforID 52plex have been selected to cover all chromosomes with an ample distribution across the genome in order to ensure the discovery of recombination-born differences even among members of complex inbred pedigrees [6].

Human identity testing using DNA has undergone an evolution from multilocus restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and less polymorphic single-locus RFLP probes to even less polymorphic STR systems, mostly to achieve laboratory automation [3]. Recently, SNPs offered a further possibility for this purpose. Future identity typing laboratories will undoubtedly utilize simpler test systems involving SNPs in order to more easily automate the laboratory process. The SNPforID 52plex assay was developed by the SNP consortium for identification purposes. Many authors have confirmed the utility of these markers; namely in severely degraded samples like bones and in other applications [16,17].

Conclusion

After revisiting some complex paternity cases and complementing the information achieved by the study of the conventional STR markers, by using the 52 SNP markers included in the SNPforID 52plex assay developed by the SNPforID Consortium, we found greatly increased PI values and a significantly reduced uncertainty in all cases investigated. SNP typing represents an extremely useful tool to complement STR information in deficient cases of disputed paternity regardless of the cause of the deficiency. However, even if the methodology used in this study is perfectly fitting for forensic casework requirements, it has its drawbacks. SNaPshot is a laborious technique if it is accomplished without some degree of automation, and, above all, the data analysis process requires a significant level of expertise to be properly held. Moreover, it is very difficult to resolve mixtures when using these markers [18]. In fact, mixture interpretation is a major drawback or limitation of forensic SNP typing ‘with the currently available typing techniques’ [3]. This remains true even if better technologies allow for enhancing mixture resolution with SNPs.

New promising technologies are being developed that hopefully would lead to the construction of SNP typing forensic kits in the near future that could provide a more user-friendly alternative to the current SNP typing methods. With regard to findings like those presented in this paper, we sincerely hope that, after implementing these more user-friendly SNP typing technologies, these markers will be included in the everyday forensic toolbox.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Butler JM, Coble MD, Vallone PM. STRs vs. SNPs: thoughts on the future of forensic DNA testing. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2007;3:200–205. doi: 10.1007/s12024-007-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amorim A, Pereira L. Pros and cons in the use of SNPs in forensic kinship investigation: a comparative analysis with STRs. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;150:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kayser M, de Knijff P. Improving human forensics through advances in genetics, genomics and molecular biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nrg2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobrino B Brión M, Carracedo A. SNPs in forensic genetics: a review on SNP typing methodologies. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;154:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pui-Yan K, Xiangning C. Detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2003;5:43–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Børsting C, Mikkelsen M, Morling N. Kinship analysis with diallelic SNPs – experiences with the SNPforID multiplex in an ISO17025 accreditated laboratory. Transfus Med Hemother. 2012;39:195–201. doi: 10.1159/000338957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez JJ, Phillips C, Børsting C, et al. A multiplex assay with 52 single nucleotide polymorphisms for human identification. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:1713–1724. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh PS, Metzer DA, Higuchi R. CHELEX® 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques. 1991;10:506–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egeland T, Mostad PF, Mevag B, Stenersen M. Beyond traditional paternity and identification cases: selecting the most probable pedigree. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;110:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pontes ML, Pinheiro MF. Autosomal SNPs study of a population sample from North of Portugal and a sample of immigrants from the Eastern Europe living in Portugal. Legal Med. 2014;16:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips C, Fang R, Ballard D, Fondevila M, Harrison C, Hyland F, Musgrave-Brown E, Proff C, Ramos-Luis E, Sobrino B, Furtado M, Syndercombe Court D, Carracedo A, Schneider PM, SNPforID Consortium Evaluation of the Genplex SNP typing system and a 49plex forensic marker panel. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2007;1:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Børsting C, Sanchez JJ, Birk AH, Bruun HQ, Hallenberg C, Hansen AJ, Hansen HE, Simonsen BT, Morling N. Comparison of paternity indices based on typing 15 STRs, 7 VNTRs and 52 SNPs in 50 Danish mother-child-father trios. Prog Forensic Genet. 2006;11:436–438. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips C, Fondevila M, García-Magariños M, Rodriguez A, Salas A, Carracedo A, Laréu MV. Resolving relationship testes that show ambiguous STR results using autosomal SNPs as supplementary markers. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2008;2:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibarra A, Martinez M, Freire-Aradas A, Fondevila M, Carracedo A, Porras L, Gusmão L. Using STR, MiniSTR and SNP markers to solve complex cases of kinship analysis. Forensic Sci Int Genet Suppl Ser. 2013;4:e91–e92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindner I, Wurmb-Schwark N von, Meier P, Fimmers R, Büttner A. Usefulness of SNPs as supplementary markers in a paternity case with 3 genetic incompatibilities at autosomal and Y chromosomal loci. Transfus Med Hemother. 2014;41:117–121. doi: 10.1159/000357989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fondevila M, Phillips C, Naveran N, Fernandez L, Salas A, Carracedo A, Laréu MV. Case report: Identification of skeletal remains using short-amplicon marker analysis of severely degraded DNA extracted from a decomposed and charred femur. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2008;2:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Børsting C, Mogensen HS, Morling N. Forensic genetic SNP typing of low-template DNA and highly degraded DNA from crime case samples. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2013;7:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butler JM, Coble MD, Vallone PM. STRs vs. SNPs: thoughts on the future of forensic DNA testing. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2007;3:200–205. doi: 10.1007/s12024-007-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]