Abstract

Objectives

Changes in cognitive function have been identified in and reported by many cancer survivors. These changes have the potential to impact patient quality of life and functional ability. This prospective longitudinal study was designed to quantify the incidence of change in cognitive function in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients throughout and following primary chemotherapy.

Methods

Eligible patients had newly diagnosed, untreated ovarian cancer and had planned to receive chemotherapy. Web-based and patient reported cognitive assessments and quality of life questionnaires were conducted prior to chemotherapy, prior to cycle four, after cycle six, and six months after completion of primary therapy.

Results

Two-hundred-thirty-one evaluable patients entered this study between May 2010 and October 2011. At the cycle 4 time point, 25.2% (55/218) of patients exhibited cognitive impairment in at least one domain. At the post-cycle 6 and 6-month follow up time points, 21.1% (44/208) and 17.8% (30/169) of patients, respectively, demonstrated impairment in at least one domain of cognitive function. There were statistically significant, but clinically small, improvements in processing speed (p < 0.001) and attention (p < 0.001) but not in motor response time (p = 0.066), from baseline through the six-month follow up time period.

Conclusions

This was a large, prospective study designed to measure cognitive function in ovarian cancer. A subset of patients had evidence of cognitive decline from baseline during chemotherapy treatment in this study as measured by the web-based assessment; however, changes were generally limited to no more than one domain.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Cognitive function, Prospective trial

1. Introduction

Many cancer patients report, and a growing body of literature supports persistent changes in cognitive function, which are characterized by impairment in memory, visuospatial ability, attention, and other executive functions (functions responsible for the management of cognitive processes) during and following cancer treatment. Neurocognitive symptoms may be associated with discrete or multiple etiologies, including direct or indirect effects of cancer on the central nervous system, co-morbid neurologic or psychiatric diagnoses, and diffuse and specific effects of cancer treatment, including radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy. Although the perception of neurocognitive decline is common among oncology patients, it is poorly understood. The potential impact of chemotherapy treatment on cognitive function is an important concern for cancer survivors. It has been documented to affect work and social functioning in many diseases [1–3]. In breast cancer, cognitive decline has been found to impact between 16 and 50% of all patients treated with chemotherapy [4,5]. A 2012 meta-analysis of 17 studies of breast cancer patients found that breast cancer patients experienced lower scores than controls on various cognitive function assessments but the declines were not large in magnitude. However, as has been learned from other conditions, even small declines in cognitive function can impact one’s ability to perform complex tasks, and noticing these declines may result in reduced confidence and further declines in performance of those tasks [6–8].

While much of what is known about changes in cognitive function in oncology has been learned from breast cancer patients, little is known about cognitive function in many other cancer populations, such as among women with ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer death and the fifth leading cause of all cancer deaths among women [9]. In 2014, it is estimated that approximately 21,980 women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and 14,270 will die of the disease [9]. Despite advances in surgical and chemotherapy intervention, most women (e.g., more than 75%) who are diagnosed with ovarian cancer will not be cured; these women will experience disease recurrence and will spend the duration of their lives undergoing periods of chemotherapy treatment to battle disease recurrence [10]. Therefore, changes in cognitive function that could impact both functional ability and quality of life are a key concern for patients who are exposed to many courses of chemotherapy. Unfortunately, in a review of research in ovarian cancer, only four published longitudinal studies were identified that evaluated the neurocognitive effects of treatment among patients with ovarian cancer [11]. These studies were small (less than 30 patients each) and all used different instruments to measure cognitive function. As a result, there were varied results with reports ranging from 80% of ovarian patients experiencing some form of cognitive problem during chemotherapy in one study to no patients in another study [12,13]. In order to better understand the magnitude of this problem in ovarian cancer, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) initiated a large prospective study to quantify the incidence of change in cognitive function in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients throughout and following primary chemotherapy.

2. Methods

All study procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the GOG and the respective Institutional Review Board of each participating institution. Eligible participants included women age 18 years or older who had a confirmed diagnosis of ovarian, primary peritoneal or fallopian tube cancer and were prescribed six courses of chemotherapy. Women were not eligible if they had ever received chemotherapy or radiation therapy or if they had any prior cancer diagnosis other than non-melanoma skin cancer. Patients were excluded if they were unable to use a keyboard, if the patient had a history of head trauma impacting cognitive ability, severe cardiovascular disease, or if they had received any form of erythropoietin in an effort to reduce the risk of baseline cognitive problems in the study population. Study enrollment took place prior to the initiation of any chemotherapy. Following provision of written informed consent, study participants completed a quality of life questionnaire (FACT-O) with a neuropathy subscale (FACT-Ntx), a survey to assess anxiety and depression (HADS), a computerized cognitive function test (HeadMinder Clinical Research Tool, CRT), and a self-report survey of patients’ perceptions of their own cognitive function (PAF) [14–18]. Participants were asked to rate on a 6-point scale, from almost always to almost never, how often they experience a particular kind of difficulty in their everyday lives on the PAF. Each response was coded from 0 to 5 and was averaged to create a summary level of cognitive impairment: low (0.0–1.25); medium (1.26–1.92); and high (1.93–4.0). For the HADS, a score of 0–7 in respective subscales is considered within normal range, scores of 8–10 are borderline, and 11 or over indicate clinical depression or anxiety, respectively. A six-point change on the FACT-O is clinically meaningful [14].

This assessment battery was completed at four time points during the study: at baseline (before chemotherapy), prior to the fourth cycle of chemotherapy, after completion of six cycles of chemotherapy, and at 6 months following completion of primary chemotherapy.

The HeadMinder CRT web-based cognitive screening test was used to objectively measure cognitive function. Three primary cognitive domains were assessed using the CRT test: processing speed (measured in seconds), motor reaction time (measured in seconds), and attention (measured as number correct or number correctly recalled). A summary score for each cognitive domain was recorded at each assessment time point. A higher score indicates slower processing or reaction time (declined performance) or increased accuracy in attention (improved performance). An impaired cognitive domain of each patient at an assessment time was defined as the increased cognitive domain score from baseline for processing speed or motor reaction and was defined as a decreased score for attention domain) ≥1.5 standard error of measurement (SEM), where and st1 is the standard deviation of the baseline value and r is the reliability coefficient for the measurement. The reliability coefficients used in this study are r = 0.8 for reaction time, r = 0.78 for processing speed, and r = 0.73 for attention.

A Cognitive Index Score (CIS) for each patient was determined by the number of impaired cognitive domains at an assessment time, which ranges 0–3 [12]. Patients with two or more cognitive domain impairments (CIS ≥ 2) during chemotherapy (prior to cycle 4 or 3 weeks post cycle 6) were considered as having possible or probable acute cognitive function impairment. If the acute cognitive function impairment is retained at 6-months post cycle 6, the impairment is considered persistent.

A sample size of 200 patients was planned to produce a two-sided 99% confidence interval (a Dunn–Sidak correction was applied to make sure the confidence level was at least 95% for all estimated intervals) for the changes in three cognitive domains during and post chemotherapy. The association between the patient-reported outcomes (cognitive function measured by the PAF, quality of life measured by the FACT-O, and depression and anxiety measured by the HADS) and cognitive function (CIS > 0 vs CIS = 0) as measured with web-based assessment (HeadMinder Clinical Research Tool, CRT) was explored by fitting a linear mixed model with the patient-reported outcomes as the dependent variable (for each test, respectively) and cognitive function (CIS score) as an exploratory variable. The relationship between patient-reported QOL (FACT-O), anxiety and depression (HADS), and patient-reported cognitive function (PAF) was explored with a linear mixed model with the FACT-O and HADS score in follow-up assessments as the dependent variables, respectively, and PAF score as an exploratory variable. Covariates included baseline patient-reported outcome scores, patient age, education, baseline ECOG performance status, and route of chemotherapy (intravenous versus intraperitoneal).

3. Results

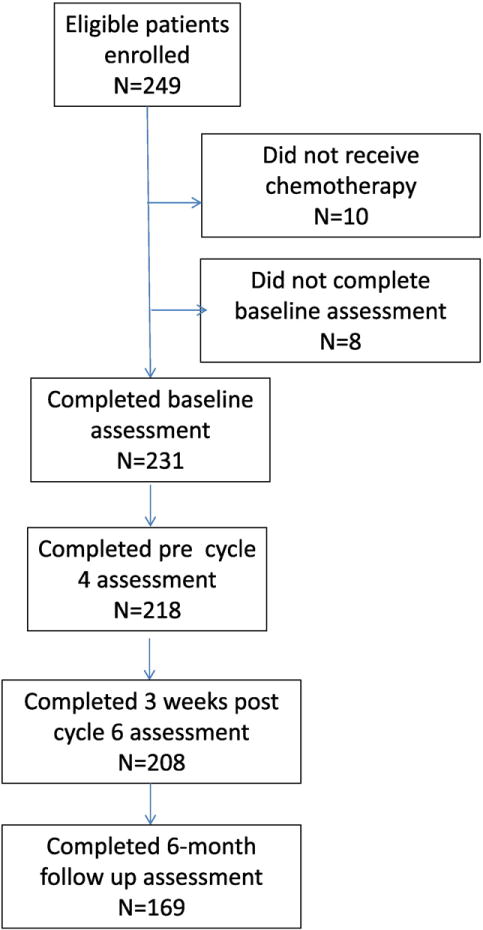

There were 249 eligible patients enrolled to this study between April 12, 2010 and October 11, 2011. Ten patients did not receive chemotherapy and were therefore excluded from the study. An additional eight patients did not complete the baseline web-based cognitive assessments and were not included in the analysis. The characteristics of the remaining 231 evaluable patients are presented in Table 1 and the patient flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible patients included in the analysis (N = 231).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 40–49 | 43 (18.6) |

| 50–59 | 90 (39.0) |

| 60–69 | 57 (24.7) |

| 70–79 | 41 (17.8) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 7 (3.0) |

| White | 195 (84.4) |

| Hispanic | 9 (3.9) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (1.3) |

| Other | 17 (7.7) |

| ECOG Performance Status | |

| 0 | 155 (67.1) |

| 1 | 71 (30.7) |

| 2 | 5 (2.2) |

| Education | |

| ≤11th grade | 9 (3.9) |

| High School | 144 (62.3) |

| Bachelor Degree | 41 (17.7) |

| Graduate Degree | 36 (15.6) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) |

| Stage | |

| I | 37 (16.0) |

| II | 20 (8.7) |

| III | 150 (64.9) |

| IV | 21 (9.1) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.3) |

| Route of administration of primary chemotherapy | |

| Intravenous | 172 (74.5) |

| Intraperitoneal | 59 (25.5) |

Fig. 1.

CONSORT patient flow diagram.

3.1. Web-based cognitive assessment

The web-based cognitive assessment data (CRT scores) at each time point are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Over time, fewer participants completed the web-based assessment, primarily due to missed visits. The raw scores for the entire study population are presented in Table 2. Overall, mean processing time (p < 0.001) and attention (p < 0.001) showed a statistically significant, but not clinically meaningful, improvement over time (Table 2). There were no significant changes over time in reaction speed.

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviation (SD) CRT scores and mean change (99% confidence interval, CI) from baseline, by cognitive domain.

| Assessment time point | Cognitive domain

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Time (seconds)a

|

Attention (# correctly recalled)b

|

Motor reaction time (seconds)a

|

|||||||

| N | Mean ± SD | Mean change (99% CI) | N | Mean ± SD | Mean change (99% CI) | N | Mean ± SD | Mean change (99% CI) | |

| Baseline | 212 | 3.80 ± 1.11 | – | 205 | 11.62 ± 3.82 | – | 229 | 0.65 ± 0.16 | – |

| Pre cycle 4 | 191 | 3.47 ± 0.80 | −0.22 (−0.35–−0.09) | 183 | 12.30 ± 3.92 | 0.39 (−0.23–1.02) | 216 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 0.013 (−0.03–0.08) |

| 3 weeks post cycle 6 | 187 | 3.45 ± 0.90 | −0.25 (−0.37–−0.12) | 171 | 12.69 ± 4.25 | 0.82 (0.15–1.49) | 206 | 0.65 ± 0.17 | 0.002 (−0.03–0.03) |

| 26 weeks post cycle 6 | 159 | 3.23 ± 0.70 | −0.45 (−0.57–−0.32) | 152 | 13.73 ± 3.93 | 1.55 (0.84–2.29) | 168 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | −0.003 (−0.03–0.02) |

| p-value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.062 | ||||||

Lower scores reflect lower performance.

Increasing scores reflect lower performance.

Additionally, the web-based CRT cognitive assessment scores were significantly associated with patient’s age. For every ten years of increasing age, processing time became slower by 0.51 seconds (s) on average (99% CI: 0.38–0.64), attention was reduced by recalling 1.23 fewer numbers correctly recalled (99% CI: −1.84–−0.61), and reaction time was slowed by 0.037 s (99% CI: 0.015–0.058). However, these changes may not be clinically meaningful.

The cognitive index score (CIS) was used to assess the number of domains that were impaired for each study participant using the web-based cognitive assessment tool (CRT). Approximately 25% (55/218) of patients had evidence of cognitive decline from baseline during chemotherapy treatment in this study (CIS ≥ 1), with only about 17% (30/169) demonstrating cognitive decline at the six-month follow up (Table 4). Patients with cognitive impairments were most likely to experience a decline in only one domain (CIS = 1), primarily attention (Table 3). Only six patients experienced declines in more than one domain (Table 4) at any point during the study.

Table 4.

Cognitive index scores (CIS).

| Time point | No. Evaluable | CIS = 0 N (%) | CIS = 1 N (%) | CIS ≥ 2 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre cycle 4 | 218 | 163 (74.8%) | 49 (22.5%) | 6 (2.7%) |

| 3 weeks post cycle 6 | 208 | 164 (78.9%) | 39 (18.8%) | 5 (1.9%) |

| 26 weeks post cycle 6 | 169 | 139 (82.3%) | 28 (16.0%) | 2 (1.2%) |

Table 3.

Number and percent of patients with impaired cognitive function, by domain.

| Time point | Processing

|

Attention

|

Motor

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluable N | Impaired N (%) | Evaluable N | Impaired N (%) | Evaluable N | Impaired N (%) | |

| Pre-cycle 4 | 191 | 9 (4.7%) | 183 | 36 (19.7%) | 216 | 16 (7.4%) |

| 3 wks post cycle 6 | 187 | 5 (2.7%) | 171 | 23 (13.5%) | 206 | 22 (10.7%) |

| 26 wks post cycle 6 | 159 | 2 (1.3%) | 152 | 18 (11.8%) | 168 | 12 (7.1%) |

There were 89 patients who exhibited cognitive impairment (CIS ≥ 1) at any of the assessment points. The exploratory analysis was found that the chemotherapy induced cognitive impairment was more likely associated with patient’s age (p = 0.011) and education level (p = 0.002). Specifically, impairment in the processing speed (p = 0.005) and motor reaction time (p = 0.0005) were associated with patient’s age, and impairment in attention was related with education level (p = 0.033). Disease stage, performance status prior to chemotherapy, and the administration route of chemotherapy (IV vs IP) were not associated with measured impairment.

3.2. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs)

Patient-reported outcome measure scores (PAF, FACT-O, and HADS) at each assessment time points by cognitive function impairment (CIS ≥ 1 vs CIS = 0) are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviations of patient-reported outcomes at each assessment time point, by cognitive index score (CIS).

| Patient reported outcome scale | Assessment time point | CIS = 0

|

CIS ≥ 1

|

p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||

| Patient assessment of own functioning (PAF)a | Pre-cycle 4 | 149 | 17.2 | 13.3 | 49 | 17.1 | 10.1 | 0.69 |

| 3 weeks post-cycle 6 | 151 | 18.7 | 13.3 | 43 | 17.8 | 13.7 | ||

| 26 weeks post-cycle 6 | 132 | 15.9 | 11.8 | 29 | 18.0 | 15.0 | ||

| Functional assessment of cancer outcomes, ovarian (FACT-O)b | Pre-cycle 4 | 147 | 103.6 | 14.6 | 49 | 104.9 | 15.8 | 0.55 |

| 3 weeks post-cycle 6 | 150 | 107.2 | 16.3 | 43 | 105.0 | 14.1 | ||

| 26 weeks post-cycle 6 | 129 | 115.9 | 13.8 | 28 | 111.4 | 14.1 | ||

| Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)a | Pre-cycle 4 | 148 | 10.1 | 6.0 | 49 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 0.56 |

| 3 weeks post-cycle 6 | 150 | 10.1 | 6.4 | 41 | 11.1 | 6.3 | ||

| 26 weeks post-cycle 6 | 131 | 8.2 | 5.3 | 29 | 9.4 | 6.2 | ||

Lower scores reflect better outcomes.

Higher scores reflect better outcomes.

When comparing patients with CIS = 0 versus those with a CIS ≥ 1 at any follow up time point (controlling for age, baseline score, assessment time, IP vs IV therapy, performance status, disease stage, and education), none of the patient-reported outcomes were found to be associated with impairment in cognitive function as defined by the CIS. In addition, the patient-reported outcomes were not associated with changes in cognitive function except for the FACT-O score, which was associated with web-based reaction time. The FACT-O score decreased an average of 10.4 points for each second of longer reaction time. While the change in FACT-O is considered a clinically meaningful difference, the associated reaction time changes were small. The mean reaction time difference was 0.65 s (Supplementary Table 2) and demonstrated little change over time. There was also no relationship between reaction time and neuropathy as reported on the FACT-Ntx. While patient-reported neuropathy symptoms increased during treatment, this was not associated with longer reaction times.

A pre-planned, exploratory analysis of the association (controlling for age, baseline score, assessment time, IP vs IV therapy, performance status, disease stage, and education) of self-reported cognitive function (PAF score) with other patient-reported outcomes, the FACT-O and HADS scores were significantly associated with the patient self-assessment of cognitive function (PAF score). For every one point of increment in PAF score, the FACT-O score declined 0.34 points (95% CI: −0.44–−0.23; p < 0.001) and HADS increased 0.15 points (95% CI: 0.11–0.19; p < 0.001). However, it is unknown how many points of change on the PAF are necessary to be clinically meaningful, and the changes in the FACT-O and HADS are small (a 6-point change on the FACT-O and change to a higher group of scores on the HADS are considered to be clinically meaningful).

4. Discussion

This was a large, prospective study designed to document objective changes in cognitive function in the ovarian cancer survivor population. There were impairments noted in at least one domain in approximately 25% of patients during the course of chemotherapy. However, only 17% demonstrated impairment at the six month follow-up. This is consistent with what has been shown in previous research among women with breast cancer treated with chemotherapy [4,5]. While this study lends support for the existence of cognitive changes for women who undergo chemotherapy, there continues to be difficulty identifying the subset of women who are at greatest risk. There does appear to be some relationship with increasing age. However, relatively low incidence of cognitive impairment in this study limits the ability to conduct research to identify strategies to reduce the risk of experiencing this problem. Without the ability to identify those likely to experience cognitive decline, the design of intervention studies need to be quite large in order to be sufficiently powered to detect a reduction in risk. At this time, research in other cancers is focused on the development of treatment strategies for patients reporting cognitive problems, but there is a need for earlier detection of patients who may be at risk of cognitive decline to minimize the impact on patient well-being.

There was no significant relationship between cognitive function and quality of life beyond the FACT-O score changes, which were not clinically meaningful. It is unclear if this relationship was limited to any particular aspect of quality of life that is measured by the FACT-O (emotional, physical, functional, social wellbeing or symptomatology).

Adding to the challenges associated with chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment is the issue of measurement. In this study, the HeadMinder screening battery of tests was used, which is far from a comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. It only assesses three functional domains. While the instrument has been shown to be correlated with other neurocognitive assessment tests, such as the TrailMaking A and B test and Digit Span test, this is a general cognitive screen only. There may be other domains of cognition affected that were not evaluated in this study. There is no objective cognitive assessment test designed to address the setting of cognitive declines associated with chemotherapy treatment. Therefore, many existing tools that were developed for other conditions may not have the sensitivity or the specificity to the problems experienced in cancer [19]. As a result, the problems faced by patients remain difficult to measure or to evaluate over time.

Despite these limitations, this study identified a subset of patients who experience changes in cognitive function during chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. Additional work must be conducted to better understand which patients experience decline, to control for potential confounding effects of concomitant medication use, and to develop strategies to minimize the impact of these problems in daily life.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

GOG-0256 prospectively evaluated changes in cognitive function and quality of life.

25% of patients experience some cognitive decline during treatment.

The changes in cognitive function were associated with age and education level.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Administrative Office (CA 27469), the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical Office (CA 37517), NRG Oncology SDMC (1 U10 CA 180822) and NRG Oncology Operations (U10CA 180868). Harrington Cancer Center provided funding for all cognitive testing and other nonstandard aspects of the study. The following Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions participated in the primary treatment studies: Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Duke University, University of Minnesota Medical Center, Northwestern University, University of Mississippi Medical Center, University of Colorado Cancer Center, University of California at Los Angeles, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Indiana University Hospital, University of Arizona Cancer Center, University of California Medical Center at Irvine, Cooper Hospital University Medical Center, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, University of Virginia, Cast Western Reserve University, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Women and Infants Hospital, Central Connecticut, Georgia Center for Oncology Research and Education, Aurora Women’s Pavilion of Aurora West Allis Medical Center, and CCOP.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.10.003.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Lisa Hess was an employee of Indiana University during the conduct and completion of this study. After completion of this work she accepted a position at Eli Lilly and Co. Dr. Robert Mannel received per capita funding for performing research through the Gynecologic Oncology Group, NCI. He also served on the Advisory Board for clinical trial development with Amgen, Advaxis, MedImmune, Astra Zeneca, Oxigene and Endocyte.

All other co-authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Lisa M. Hess, Email: lmhess@iupui.edu.

Helen Q. Huang, Email: hhuang@gogstats.org.

Alexandra L. Hanlon, Email: al_hanlon@comcast.net.

William R. Robinson, Email: wrobinso@tulane.edu.

Rhonda Johnson, Email: rjohnson7@kumc.edu.

Setsuko K. Chambers, Email: schambers@uacc.arizona.edu.

Robert S. Mannel, Email: Robert-mannel@ouhsc.edu.

Larry Puls, Email: lpuls@ghs.org.

Susan A. Davidson, Email: susan.davidson@ucdenver.edu.

Michael Method, Email: mmethod@mhopc.com.

Shashikant Lele, Email: Shashi.lele@roswellpark.org.

Laura Havrilesky, Email: havri001@mc.duke.edu.

Tina Nelson, Email: tina-nelson@ouhsc.edu.

David S. Alberts, Email: dalberts@uacc.arizona.edu.

References

- 1.Hopkins RO, Jackson JC. Long-term neurocognitive function after critical illness. Chest. 2006;130:869–878. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tannock IF, Ahles TA, Ganz PA, Van Dam FS. Cognitive impairment associated with chemotherapy for cancer: report of a workshop. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2233–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Correa DD, Ahles TA. Neurocognitive changes in cancer survivors. Cancer J. 2008;14:396–400. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermelink K, Untch M, Lux MP, Kreienberg R, Beck T, Bauerfeind I, et al. Cognitive function during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: results of a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal study. Cancer. 2007;109:1905–1913. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taillibert S, Voillery D, Bernard-Marty C. Chemobrain: is systemic chemotherapy neurotoxic? Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:623–627. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f0e224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood R, Bandura A. Impact of conceptions of ability on self-regulatory mechanisms and complex decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:407–415. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medalia A, Revheim N. Dealing with cognitive dysfunction associated with psychiatric disabilities. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(1):17–25. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Njegovan V, Hing MM, Mitchell SL, Molnar FJ. The hierarchy of functional loss associated with cognitive decline in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M638–6343. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers SK, Hess LM. Ovarian Cancer Prevention. In: Alberts DS, Hess LM, editors. Fundamentals of Cancer Prevention. Springer Verlag; Heidelberg: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correa DD, Hess LM. Cognitive function and quality of life in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess LM, Chambers SK, Hatch K, Hallum A, Janicek MF, Buscema J, et al. Pilot study of the prospective identification of changes in cognitive function during chemotherapy treatment for advanced ovarian cancer. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hensley ML, Correa DD, Thaler H, Wilton A, Venkatraman E, Sabbatini P, et al. Phase I/II study of weekly paclitaxel plus carboplatin and gemcitabine as first-line treatment of advanced-stage ovarian cancer: pathologic complete response and longitudinal assessment of impact on cognitive functioning. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basen-Engquist K, Bodurka-Bevers D, Fitzgerald MA, Webster K, Cella D, Hu S, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy—ovarian. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1809–1817. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calhoun EA, Welshman EE, Chang CH, Lurain JR, Fishman DA, Hunt TL, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy/gynecologic oncology group—neurotoxicity (Fact/GOG-Ntx) questionnaire for patients receiving systemic chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:741–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2003.13603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erlanger DM, Kaushik T, Broshek D, Freeman J, Feldman D, Festa J. Development and validation of a web-based screening tool for monitoring cognitive status. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2002;17:458–476. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chelune GJ, Heaton RK, Lehman RA. Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients‘ complaints of disability. In: Goldstein G, Tarter RE, editors. Advances in Clinical Neuropsychology. Plenum Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers CA, Wefel JS. The use of the mini-mental state examination to assess cognitive functioning in cancer trials: no ifs, ands, buts, or sensitivity. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3557–3558. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.