Abstract

Background

Long-course preoperative chemoradiotherapy (chemo-RT) improves outcomes for rectal cancer patients, but acute side effects during treatment may cause considerable patient discomfort and may compromise treatment compliance. We developed a dose-response model for acute urinary toxicity based on a large, single-institution series.

Materials and Methods

345 patients were treated with (chemo-)RT for primary rectal cancer from Jan ‘07 to May ‘12. Urinary toxicity during RT was scored prospectively using the CTCAE v 3.0 cystitis score (grade 0 to 5). Clinical variables and radiation dose to the bladder were related to graded toxicity using multivariate ordinal logistic regression. Three models were optimized, each containing all available clinical variables and one of three dose metrics: Mean dose (Dmean), equivalent uniform dose (EUD), or relative volume given x Gy or above (dose cutoff model, Vx). The optimal dose metric was chosen using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Results

Grade 1 cystitis was experienced by 138 (40%), grade 2 by 39 (11%) and grade 3 by 2 (1%) patients, respectively. Dose metrics were significantly correlated with toxicity in all models, but the dose cutoff model provided the best AIC value. The only significant clinical risk factors in the Vx model were male gender (p=0.006) and brachytherapy boost (p=0.02). Reducing the model to include gender, brachytherapy boost and Vx yielded odds ratios ORmale = 1.82 (1.17 to 2.80), ORbrachy = 1.36 (1.02 to 1.80 for each 5 Gy), x = 35.1 Gy (28.6 to 41.5 Gy). The predicted risk of grade 2 and above cystitis ranged from 2% to 26%.

Conclusion

Acute cystitis correlated significantly with radiation dose to the bladder; the dose-cutoff model (V35Gy) was superior to Dmean and EUD models. Male gender and brachytherapy boost increased the risk of toxicity. Wide variation in predicted risks suggests room for treatment optimization using individual dose constraints.

Introduction

Patients undergoing radiotherapy (RT) for pelvic malignancies will frequently have their bladder partially or fully irradiated to substantial doses, with a resulting risk of acute and late radiation induced urinary toxicity [1,2]. This risk is relatively well-studied in patients treated for bladder [2], prostate [3] and gynaecological [4] cancers, but much less so in rectal cancer patients, despite long-course, preoperative (chemo-)RT being part of the standard treatment regimen for locally advanced rectal cancer [5]. Urinary toxicity is, nevertheless, a genuine concern for this patient group [6]. If estimates of the dose-response relationship for urinary toxicity are improved, modern RT planning techniques may allow for optimizations of dose distributions to minimize the risk of toxicity [7].

To carry out dose plan optimization, relevant dose constraints and the nature of volume effects in organs at risk have to be established. This has long been the focus of extensive research efforts in other cancer sites [8], but limited work has been performed for preoperative RT of rectal cancer – and what little that has been done has mainly focused on gastrointestinal toxicity. This study examined the relationship between dose to the bladder and the risk of acute toxicity for a large single-institution cohort of patients receiving long-course neoadjuvant RT for locally advanced rectal cancer. Furthermore, we also investigated clinical factors that may affect this dose-response.

Materials and Methods

This study included patients treated at our institution from January 2007 to May 2012 with long-course (chemo-)RT for rectal cancer. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were treated post-operatively, were treated for local recurrence of primarily operated tumours, did not have available dose or toxicity data, or received fever than 5 fractions of the planned treatment.

Acute urinary toxicity (cystitis by CTCAE v3.0) was scored prospectively by trained RT nurses during the course of the treatment, with at least weekly evaluation. Grade 1 cystitis is mainly asymptomatic; grade 2 is defined by increased frequency, dysuria, or macroscopic hematuria; and grade 3 indicates a need for IV pain medications, bladder irrigation, or transfusions. All toxicity scores were retrospectively compared with treatment charts and notes from the responsible physicians to ensure the accuracy of the scoring. The highest toxicity score registered during treatment was used for subsequent analysis.

Patient characteristics were extracted retrospectively from patient charts. Disease stage, gender, age, as well as details of chemotherapy, if given, were recorded. Details of RT treatment, including dose/fractions prescribed and delivered, were extracted from the record and verification system in the radiotherapy clinic and confirmed by chart review. Treatment technique and positioning (prone/supine) were verified by individual plan review.

Treatment planning was performed using Oncentra Masterplan (Nucletron, An Elekta Company, Netherlands). Plans consisted of either 3D conformal (3D-CRT) plans, typically using a 3-field technique with combined 6 MV posterior fields and lateral 18 MV wedge fields, or intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) plans using a 5- or 7-field technique with 6 MV photon beams. Dose distributions were calculated using a pencil beam convolution algorithm taking tissue heterogeneity into account. 3 patients were re-planned with IMRT a few fractions into the treatment; for those patients a weighted sum of the plans were used for the study, and the patients were coded as receiving IMRT. A fraction of the patients received an external boost to the tumour only using conformal beams (see Table 1); in that case the sum of the external treatment plans was used. Another fraction of patients received an intracavitary brachytherapy boost to the tumour, using an endorectal applicator [9,10]. Dose distributions for organs at risk were not available for brachytherapy, and hence brachytherapy dose was included as a separate factor in the analysis (see modelling details below). Treatment plans for patients who did not complete the full course of treatment (typically due to GI toxicity) were altered to reflect the actual dose delivered. No bladder preparation protocol was employed.

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics

| Clinical disease stage: | |

| - T | T1-2: 17 (5) |

| T3: 247 (72) | |

| T4: 81 (23) | |

| - N | N0: 44 (13) |

| N1: 138 (40) | |

| N2: 159 (46) | |

| ND: 4 (1) | |

| - M | M0: 327 (95) |

| M1: 17 (5) | |

| ND: 1 (0) | |

| Gender | Female: 135 (39) |

| Male: 210 (61) | |

| Median age (range) | 67 years (26 – 87 years) |

| Median tumor dose primary external treatment (range) | 50.4 Gy (27.0 – 62.0 Gy) |

| Median lymph node dose (range) | 50.4 Gy (27.0 – 50.4 Gy) |

| Sequential external boost dose (38 pts) | 6.0 Gy: 29 (8) |

| 10 Gy: 2 (1) | |

| 12 Gy: 7 (2) | |

| Intracavitary brachytherapy boost dose (137 pts) | 5 Gy: 91 (26) |

| 10 Gy: 46 (13) | |

| Treatment technique | 3D-CRT: 229 (66) |

| IMRT: 116 (34) | |

| Treatment position | Prone: 88 (26) |

| Supine: 257 (74) | |

| Chemotherapy (285 pts) | UFT: 270 (78) |

| Other: 15 (4) | |

| Median bladder volume (range) | 177 cm2 (35 – 902 cm2) |

| Median Dmean for the bladder (range) | 41.4 Gy (14.1 – 61.9 Gy) |

| Median relative V35Gy for the bladder (range) | 0.71 (0.00 – 1.00) |

| Acute urinary toxicity | |

| - Grade 0 | - 166 (48) |

| - Grade 1 | - 138 (40) |

| - Grade 2 | - 39 (11) |

| - Grade 3 | - 2 (1) |

3D-CRT: 3D conformal radiotherapy. IMRT: intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Numbers are absolute number of patients, with percentages of entire cohort (345 patients) in brackets, where nothing else is indicated.

Bladder delineation was performed by experienced radiation oncologists. The entire bladder, including both the bladder wall and the urine compartment, was delineated as one single structure. Plans, structure sets and dose distributions were imported into the Computational Environment for Radiotherapy Research (CERR) [11], and dose volume histograms (DVHs) were extracted. No correction for the effect of local fraction size was used in the primary fit; however, see details below for secondary testing for model sensitivity to fraction-size correction.

Multivariate ordinal logistic modelling was used to correlate dose and clinical or treatment related factors to graded toxicity scores. The risk p of toxicity of grade i or above was given by

| (1) |

where ORj = exp(bj) are odds ratios for toxicity in patients with or without clinical variable Yj, and D is a dose metric. Three DVH reduction methods, each producing a single dose metric, were used: Mean dose (Dmean), equivalent uniform dose (EUD), or relative organ volume exposed to x Gy or above (dose cutoff model, Vx). This allowed for examination of dose-volume effects for the bladder. Specifically, the EUD for a dose distribution {vi,di} was calculated as [12]:

| (2) |

where a is a parameter describing the relative importance of high doses: EUD→Dmean for a→1 and EUD→Dmax for a→∞. The following clinical or treatment related variables were considered: Gender, use of chemotherapy, planning technique (IMRT vs 3D-CRT) and positioning (prone vs supine) were included as binary variables; age and prescribed brachytherapy boost dose as continuous variables. Three multivariate ordinal logistic models, each containing all available clinical variables and a single dose metric (Dmean, EUD or Vx) were optimized separately. For the EUD and dose cutoff models, the DVH reduction method (i.e. the value of the a and x parameters) was optimized as part of the full model optimization.

Model parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The three models were compared using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [13]: AIC = 2*k – 2*ln(L), where k is the number of parameters in the model, ln(L) is the log-likelihood function, and inclusion of dose-volume effects, by either a dose cutoff x or the EUD parameter a, increased the number of variables by one. The preferred model, i.e. the model which provided the optimal compromise between best fit to data and least complexity, was taken as the one resulting in the lowest AIC value. This model was subsequently refitted with only the clinical variables found to be significant (as estimated using likelihood ratio tests) in the full multivariate model. Model calibration was checked by binning patients into 6 equally sized risk groups, based on predicted risk of toxicity, and plotting mean predicted risk versus mean observed risk for each group. Goodness-of-fit was examined using the Fagerland-Hosmer test [14], with 6 risk groups for each response level.

To test model sensitivity to fraction-size effects, the final model was re-fitted, limiting the fit to patients with no external boost, and converting all doses to equieffective dose in 2 Gy fractions, with α/β = 10 Gy, the EQD2α/β=10Gy according to the linear-quadratic model. Dependence of the dose cutoff on RT technique was examined by comparing fit quality for a range of dose cutoff values (x) for patients with IMRT and 3D-CRT treatment plans. Furthermore, optimal dose cutoffs were found for IMRT and 3D-CRT, respectively, and the predictive value for an optimal cutoff found for IMRT on 3D-CRT treatments (and visa versa) were examined graphically and by Fagerland-Hosmer test statistics.

All statistical analyses were performed in MATLAB® (2010b, The MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA). Two-sided p-values of 0.05 or less were considered significant. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for fitted parameter values were obtained from a bootstrapping procedure drawing 104 random samples with replacement from the original dataset and estimating the CI as the range from the 2.5 to the 97.5 percentile of the bootstrap estimates.

Results

A total of 407 patients were treated in the time period considered, out of which 345 patients were included in the analysis. See Figure A1 in the supplementary material (available online at http//www.informahealthcare.com) for details of patients excluded from the study. Patient and treatment characteristics can be found in Table 1. The majority of patients were treated with one of two external beam radiotherapy schedules: Either 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions to both tumour and elective lymph nodes, or 60 Gy to the tumour and 50 Gy to the lymph nodes in 30 fractions, using a concomitant boost technique. Concomitant chemotherapy, administered to 285 patients, was primarily peroral UFT (300 mg/m2) and L-leucovorin (7.5 mg) daily on RT treatment days. The mean dose to the bladder ranged from 14 Gy to 62 Gy, with a fairly wide variation in organ dose distributions (see Figure A2 in the supplementary material). Urinary toxicity was generally mild; with almost half of the patients experiencing no toxicity at all, and only 12% of cases had a score of 2 or higher. Only 2 patients experienced grade 3 urinary toxicity, and scores were consequently binned as grade 0, grade 1, and grade 2 and above.

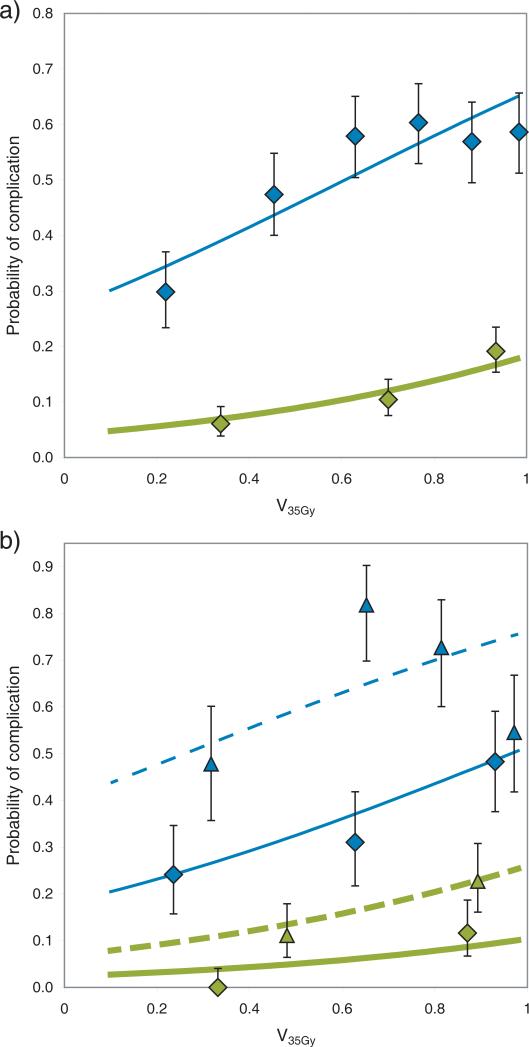

All tested models demonstrated a significant relationship between dose to the bladder and toxicity. Table 2 contains the results for model optimization for each of the three dose-volume metrics. The dose cutoff model, with x = 35 Gy, had the lowest AIC value, and was hence selected for investigation of the effect of clinical factors. Figure 1a shows the relationship between V35Gy and the risk of at least grade 1 or at least grade 2 toxicity (for the sake of illustration, other risk factors have been disregarded so that the figure represents the dose-volume-only model).

Table 2.

Model fit quality for different dose metrics

| Dose metric | ln(L) | k | AIC | Volume parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean dose, Dmean | −319.9 | 9 | 657.7 | - |

| EUD | −319.9 | 10 | 659.7 | a = 1.27 (−8.49 – 4.12) |

| Dose cutoff, Vx | −318.4 | 10 | 656.8 | x = 35.4 Gy (30.2 – 41.5 Gy) |

Results of ordinal logistic model fits relating dose metrics to the risk of acute urinary toxicity. All models included 6 clinical variables (brachytherapy dose, gender, age, chemotherapy, treatment technique, and treatment position).

EUD: Equivalent Uniform Dose. ln(L): the natural logarithm of the likelihood of the model fit. k: total number of parameters in model. AIC: Akaikes Information Criterion. Numbers in brackets represent 95% confidence intervals for the volume parameters.

Figure 1.

Relationship between relative volume of the bladder receiving at least 35 Gy (V35Gy) and the risk of grade 1 or above (thin line, blue) or grade 2 and above (thick line, green) acute urinary toxicity. Data points represent observed toxicity (with 68% confidence intervals), fitted lines represent fit to the logistic model (Eq 1). a) Dose-response taking only the dose metric, and no additional risk factors, into account. b) Dose-response for patients with the highest risk (male patients receiving a brachy therapy boost, dashed line / triangles), and dose-response for patients with the lowest risk (female, no brachytherapy, full line / diamonds). The fit to the logistic model takes V35Gy, gender and brachytherapy (as a binary variable) into account.

Table 3 provides the parameter values for the dose cutoff model fit. Only brachytherapy dose (p=0.02, OR=1.41 per 5 Gy) and male gender (p=0.006, OR=1.86) significantly increased the risk of urinary toxicity, while age (p=0.63, OR=0.95 per 10 years), chemotherapy (p=0.40, OR=0.76), treatment planning technique (p=0.86, OR=0.95 for IMRT) and positioning (p=0.11, OR=0.61) had no significant effect on the dose-response. A reduced model fit taking only V35Gy, brachytherapy dose and gender into account is provided in Table 3 as well. Figure 1b shows the additional effects of patient and treatment related risk factors, by comparing the response functions for patients with highest risk (male, brachytherapy boost) and lowest risk (female, no brachytherapy boost). In contrast to the model in Table 3, patients were classified as receiving/not receiving brachytherapy, rather than considering brachytherapy dose as continuous variable, for clarity.

Table 3.

Ordinal logistic model fits for dose cut-off model

| Parameter | All clinical factors | Only significant clinical factors |

|---|---|---|

| b0,1 | −0.62 (−2.47;1.17) | −1.55 (−2.22;−0.86) |

| b0,2 | −2.84 (−4.67;−1.02) | −3.75 (−4.48;−2.99) |

| b1 | 1.30 (0.29;2.25) | 1.68 (0.80;2.49) |

| bbrachy-dose | 0.069 (0.008; 0.129) | 0.061 (0.004;0.118) |

| bmale | 0.62 (0.16;1.06) | 0.60 (0.16;1.03) |

| bage | −0.005 (−0.026;0.018) | - |

| bchemo | −0.27 (−0.89;0.39) | - |

| bIMRT | −0.05 (−0.56;0.48) | - |

| bprone | −0.49 (−1.10;0.08) | - |

Ordinal logistic model fits for the dose cutoff (Vx) model. Optimal fit was found for ~35 Gy cutoff (35.4 Gy, 95% CI 30.2–41.5, for model with all factors, and 35.1 Gy, 95% CI 28.6–41.5, for significant factors only). Numbers indicate parameter values (Eq 1), numbers in brackets represent 95% confidence intervals.

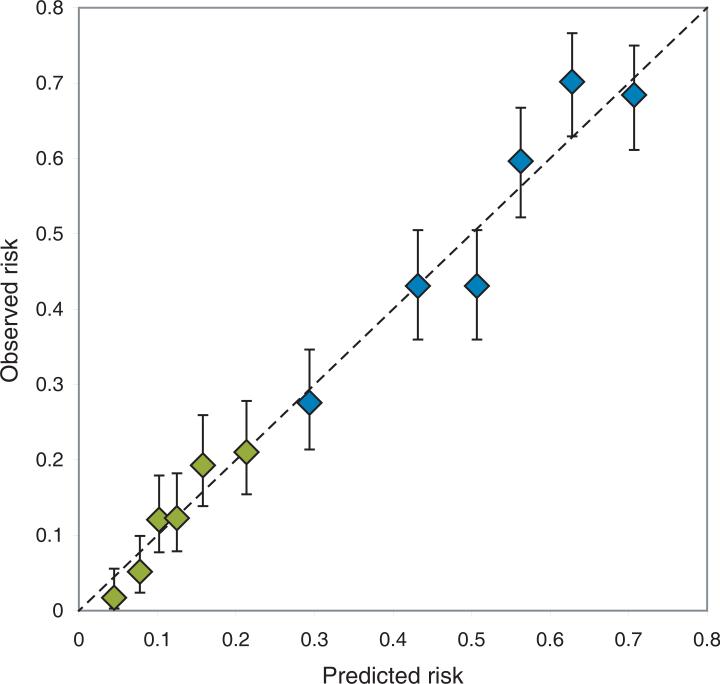

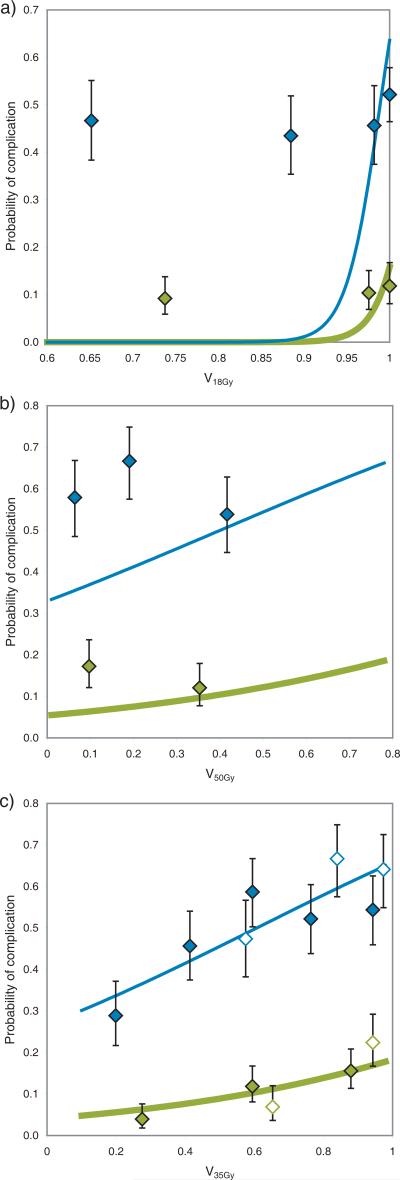

Model performance for the reduced model (V35Gy, gender and brachytherapy dose) is illustrated in Figure 2, comparing predicted and observed toxicity for increasing levels of predicted risk. The p-value for goodness-of-fit was 0.71, suggesting good agreement between predicted and observed number of events. Adjusting for fraction-size effects did not improve or alter the model: Optimal dose cutoff was found to be x = 33 Gy when correcting all doses to equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) with α/β = 10 Gy, which is almost exactly EQD2α/β=10Gy for 35 Gy in 28 fractions. Dependence of the dose cutoff value on treatment technique turned out to be strong: Figure 3 demonstrates model fit quality of the Vx model for a range of dose levels (x), for both the full patient cohort and for 3D-CRT and IMRT treated patients separately. Model fit quality is estimated by the log likelihood divided by the number of patients in the model fit; i.e. higher values indicate better fit to the clinical data. As seen, the optimal dose cutoff found for patients treated with 3D-CRT alone is ~50 Gy, while the optimal cutoff for IMRT patients is ~18 Gy. Figures 4a and 4b illustrate the poor performance of a model based on an optimal cutoff found in one group for predicting toxicity for patients treated with the alternative technique. The Fagerland-Hosmer test using each model on the other group resulted in p<0.001, indicating clear disagreement between predicted and observed toxicity. Figure 4c shows an apparent improvement of the generalizability of the model based on both treatment techniques (p=0.49).

Figure 2.

Plot of predicted versus observed toxicity, illustrating the model calibration. Patients have been grouped by increasing risk, as predicted by a logistic model including V35Gy, gender and brachytherapy dose. Blue diamonds (upper 6 points): Grade 1 and above cystitis. Green diamonds (lower 6 points): Grade 2 and above cystitis. Lack of calibration is indicated by deviance from the identity line (dotted line). Error bars show 68% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Model fit quality of Vx model for all dose levels (x), estimated by the log likelihood divided by the number of patients in the model fit. Higher values indicate better fit to the clinical data. Black line: All patients in cohort. Dashed, blue line: Patients treated with 3D conformal (3D-CRT) treatment plans. Dotted, green line: Patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) treatment plans.

Figure 4.

Optimal dose cutoff model for acute toxicity for patients treated with a) intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT, V18Gy), b) 3D conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT, V50Gy ), and c) the total patient cohort (V35Gy). Figures a) and b) additionally show the observed response for the other patient group (3D-CRT in a) and IMRT in b)). Figure c) shows observed response for all patients (solid diamonds: 3D-CRT, empty diamonds: IMRT). Thin, blue lines and diamonds: Risk of grade 1 or above acute cystitis. Thick, green lines and diamonds: Risk of grade 2 and above acute cystitis. Uncertainty bars indicate 68% confidence levels.

Discussion

We have presented the results of dose-response modelling for acute urinary toxicity for a large series of rectal cancer patients treated with long-course (chemo-)RT. We additionally studied dose-volume effects for acute urinary toxicity by examining various DVH reduction methods, and studied patient and treatment related factors influencing the dose-response estimations. A dose cut-off of ~35 Gy yielded the closest correlation with the observed toxicity; male gender and brachytherapy boost increased the risk of side effects.

Dose-volume effects for urinary toxicity have, to the best of our knowledge, not previously been studied for rectal cancer patients. In general, studies of prostate cancer and gynaecological cancer patients have struggled to establish dose-response relationships for the bladder [1,15], but those who have succeeded predominantly propose volumes exposed to high doses (>75 Gy) as the main factor in the development of late toxicity [16]. This may, however, be related to the type of injury (typically focal bladder injury, rather than global injury) which is observed and reported in those dose ranges. A few studies of prostate cancer patients [17,18] have indicated a relationship between low dose levels (V20Gy-V30Gy) and acute and late toxicity, while studies of RT for bladder cancer, where the disease itself may affect the scoring of toxicity, have shown ~50 Gy to be the limiting dose range for large bladder volumes [2]. The present study included dose distributions with volumes receiving up to 66 Gy, but no influence of those high dose levels was seen.

Clinical factors may hamper the establishment of dose-response relationships for normal tissue toxicity, such as the effects of patient and treatment related factors [19]. We found a clear effect of male gender on the observed levels of toxicity, independently of the dose to the bladder. This is in contrast to Bruheim et al [6], who found a significantly increased level of late urinary toxicity in females after RT for rectal cancer compared to non-irradiated patients; they did not, however, correct for the actual dose delivered to the bladder. We found no interaction between gender and brachytherapy dose (data not shown), hence this is unlikely to explain the increased levels of acute toxicity observed in males in our patient cohort.

Inclusion of a brachytherapy boost in the RT regimen was also found to increase the risk of acute toxicity. Brachytherapy was included as a treatment related variable, rather than as a contributing factor to the total dose to the bladder. Based on very preliminary experiences from MRI based brachytherapy at our institution, a 5 Gy brachytherapy fraction will contribute on average ~1 Gy to the Dmean and ~2 Gy to the hottest 1 cm3 of the bladder wall. It seems unlikely that the observed OR=1.4 for each 5 Gy brachytherapy dose can be explained purely by this contribution to the bladder dose. We therefore speculate that irradiation of other sensitive structures, such as the urethra, may play a role.

Up until recently, dose-volume constraints for organs at risk have been of little relevance for rectal cancer dose planning, since even standard 3D-CRT techniques allow for very limited optimization of dose to normal tissue. The introduction of IMRT [20] and similar modern techniques offers possibilities to alter the distribution of dose in the normal tissue [7]. This may prove to be of additional relevance if dose intensification [21] or adaptive treatments [22] are to be attempted. Our patient cohort had predicted incidences of grade 2 and above toxicity ranging from <5% up to >20%, which suggests that there could be room for more individual optimization of the planned dose to organs at risk. The modelling results indicate that this could be achieved by minimizing the relative V35Gy to the bladder, potentially with dose constraints stratified for clinical risk groups.

It is worth noting, however, that the current study questions the generalizability of optimization constraints for IMRT based on data from patient populations treated with more traditional techniques. This is in line with the findings of studies in head and neck cancer [23] and lung cancer [24]. As demonstrated in Figures 4a and 4b, dose cutoffs from 3D-CRT only are not necessarily applicable for IMRT treatments (and visa versa) in our patient cohorts. A larger variation in planning techniques and resulting dose distributions in a dataset allows for better model optimization as well as results that appear more generalizable (Figure 4c). (Note, however, that Figures 4a-b represent true independent validation sets, whereas the patient population (i.e. the data points) in Fig 4c is also the one used in the optimization of the depicted model.) The observed differences between models optimized for for 3D-CRT and for IMRT may be due to strong correlations between high and intermediate dose levels for the 3D-CRT treatments (which complicates model optimization). Alternatively, the observations could possibly reflect differences in the interaction between dose distributions and variations in bladder filling and positioning during treatment for the two planning techniques. Thus the results may indicate that the reduction of 3D dose distributions to DVH's, which is performed in almost all studies, is in itself problematic.

In the same vein, the difficulty in establishing dose-response models for urinary toxicity [1] has partly been attributed to the doses derived from the planning CT scan not being representative for actual dose delivered during the treatment course due to inter- and intra-fraction bladder motion and variation in filling [15]. The present study only considered dose to the bladder as estimated from the planning CT scan. While this is probably a limitation of the ability to accurately understand the dose-response, it will likely reflect the information available at the time of treatment planning in routine clinical practice for many years to come.

Acute toxicity is usually manageable and self limiting, and the clinical relevance of dose constraints based on acute, low grade urinary toxicity might not be obvious. However, strong correlations have been observed between early and late urinary toxicity, at least in part due to consequential late effects [18,25,26]. Thus examination of acute urinary toxicity may be valuable in providing insight into the factors affecting the organ response to radiation, such as dose-volume effects and the impact of patient and treatment related factors. This approach may be even more relevant for rectal cancer patients, where the intervening surgery masks observation and scoring of late complications [27]. From a research perspective, attempting validation of early urinary toxicity as a surrogate marker for late bladder side effects should be considered in series of rectal cancer patients with reliable late toxicity data. Additionally, the impact of treatment-induced urinary toxicity on patient reported quality of life needs closer study in rectal cancer patient cohorts.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a significant dose-volume relationship for acute urinary toxicity; among the dose-volume metrics considered the best fit was provided by a V35Gy dose cutoff model. The results are based on a large patient cohort (345 patients), with a good variation in dose distributions to the bladder (including doses >60 Gy) and with careful toxicity scoring. While the findings should be validated in a prospectively collected, independent cohort – where also the dose-response for late toxicity should be examined – the results represent the current best data for urinary toxicity dose-volume dependence for this patient group. The wide variation in predicted toxicity in our patient cohort leaves ample room for more individualized risk prediction and treatment optimization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ALA is supported by CIRRO - The Lundbeck Foundation Center for Interventional Research in Radiation Oncology and The Danish Council for Strategic Research, and by the Region of Southern Denmark. IRV is supported by the Global Excellence in Health program of the Capital Region of Denmark. SMB is supported in part by grant no. P30 CA 134274-04 from the NCI. The authors are thankful for the assistance of Finn Laursen with collection of radiotherapy treatment plans.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Notification

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplementary figures A1-2 to be found online, at http://www.informahealthcare.com.

References

- 1.Viswanathan AN, Yorke ED, Marks LB, Eifel PJ, Shipley WU. Radiation dose-volume effects of the urinary bladder. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks LB, Carroll PR, Dugan TC, Anscher MS. The response of the urinary bladder, urethra, and ureter to radiation and chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1257–80. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00431-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelefsky MJ, Levin EJ, Hunt M, Yamada Y, Shippy AM, Jackson A, et al. Incidence of late rectal and urinary toxicities after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1124–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eifel PJ, Levenback C, Wharton JT, Oswald MJ. Time course and incidence of late complications in patients treated with radiation therapy for FIGO stage IB carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:1289–300. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00118-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2479–516. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruheim K, Guren MG, Skovlund E, Hjermstad MJ, Dahl O, Frykholm G, et al. Late side effects and quality of life after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1005–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbea L, Ramos LI, Martínez-Monge R, Moreno M, Aristu J. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) vs. 3D conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT) in locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC): dosimetric comparison and clinical implications. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deasy JO, Muren LP. Advancing our quantitative understanding of radiotherapy normal tissue morbidity. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:577–9. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.907055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen JW, Jakobsen A. The importance of applicator design for intraluminal brachytherapy of rectal cancer. Med Phys. 2006;33:3220–4. doi: 10.1118/1.2207143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakobsen A, Ploen J, Vuong T, Appelt A, Lindebjerg J, Rafaelsen SR. Dose-effect relationship in chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomized trial comparing two radiation doses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:949–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deasy JO, Blanco AI, Clark VH. CERR: a computational environment for radiotherapy research. Med Phys. 2003;30:979–85. doi: 10.1118/1.1568978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niemierko A. A generalized concept of equivalent uniform dose (EUD) Med Phys. 1999;26:1100. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19:716–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagerland MW, Hosmer DW. A goodness-of-fit test for the proportional odds regression model. Stat Med. 2013;32:2235–49. doi: 10.1002/sim.5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosewall T, Catton C, Currie G, Bayley A, Chung P, Wheat J, et al. The relationship between external beam radiotherapy dose and chronic urinary dysfunction--a methodological critique. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorino C, Valdagni R, Rancati T, Sanguineti G. Dose-volume effects for normal tissues in external radiotherapy: pelvis. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:153–67. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlsdóttir A, Johannessen DC, Muren LP, Wentzel-Larsen T, Dahl O. Acute morbidity related to treatment volume during 3D-conformal radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harsolia A, Vargas C, Yan D, Brabbins D, Lockman D, Liang J, et al. Predictors for chronic urinary toxicity after the treatment of prostate cancer with adaptive three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy: dose-volume analysis of a phase II dose-escalation study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appelt AL, Vogelius IR, Farr KP, Khalil A a, Bentzen SM. Towards individualized dose constraints: Adjusting the QUANTEC radiation pneumonitis model for clinical risk factors. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:605–12. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.820341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuelian JM, Callister MD, Ashman JB, Young-Fadok TM, Borad MJ, Gunderson LL. Reduced acute bowel toxicity in patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1981–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appelt AL, Pløen J, Vogelius IR, Bentzen SM, Jakobsen A. Radiation dose-response model for locally advanced rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Passoni P, Fiorino C, Slim N, Ronzoni M, Ricci V, Di Palo S, et al. Feasibility of an adaptive strategy in preoperative radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer with image-guided tomotherapy: boosting the dose to the shrinking tumor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beetz I, Schilstra C, van Luijk P, Christianen MEMC, Doornaert P, Bijl HP, et al. External validation of three dimensional conformal radiotherapy based NTCP models for patient-rated xerostomia and sticky saliva among patients treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2012;105:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker SL, Mohan R, Liengsawangwong R, Martel MK, Liao Z. Predicting pneumonitis risk: a dosimetric alternative to mean lung dose. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:522–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dörr W, Bentzen SM. Late functional response of mouse urinary bladder to fractionated X-irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 1999;75:1307–15. doi: 10.1080/095530099139476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dörr W, Hendry JH. Consequential late effects in normal tissues. Radiother Oncol. 2001;61:223–31. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallner C, Lange MM, Bonsing B a, Maas CP, Wallace CN, Dabhoiwala NF, et al. Causes of fecal and urinary incontinence after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer based on cadaveric surgery: a study from the Cooperative Clinical Investigators of the Dutch total mesorectal excision trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4466–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.