Abstract

Background

Myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock is frequently complicated by acute kidney injury. We examined the influence of acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) on risk of chronic dialysis and mortality, and assessed the role of comorbidity in patients with cardiogenic shock.

Methods

In this Danish cohort study conducted during 2005–2012, we used population-based medical registries to identify patients diagnosed with first-time myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock and assessed their AKI-RRT status. We computed the in-hospital mortality risk and adjusted relative risk. For hospital survivors, we computed 5-year cumulative risk of chronic dialysis accounting for competing risk of death. Mortality after discharge was computed with use of Kaplan-Meier methods. We computed 5-year hazard ratios for chronic dialysis and death after discharge, comparing AKI-RRT with non-AKI-RRT patients using a propensity score-adjusted Cox regression model.

Results

We identified 5079 patients with cardiogenic shock, among whom 13 % had AKI-RRT. The in-hospital mortality was 62 % for AKI-RRT patients, and 36 % for non-AKI-RRT patients. AKI-RRT remained associated with increased in-hospital mortality after adjustment for confounders (relative risk = 1.70, 95 % confidence interval (CI): 1.59–1.81). Among the 3059 hospital survivors, the 5-year risk of chronic dialysis was 11 % (95 % CI: 8–16 %) for AKI-RRT patients, and 1 % (95 % CI: 0.5–1 %) for non-AKI-RRT patients (adjusted hazard ratio: 15.9 (95 % CI: 8.7–29.3). The 5-year mortality was 43 % (95 % CI: 37–53 %) for AKI-RRT patients compared with 29 % (95 % CI: 29–31 %) for non-AKI-RRT patients. The adjusted 5-year hazard ratio for death was 1.55 (95 % CI: 1.22–1.96) for AKI-RRT patients compared with non-AKI-RRT patients. In patients with comorbidity, absolute mortality increased while relative impact of AKI-RRT on mortality decreased.

Conclusion

AKI-RRT following myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock predicted elevated short-term mortality and long-term risk of chronic dialysis and mortality. The impact of AKI-RRT declined with increasing comorbidity suggesting that intensive treatment of AKI-RRT should be accompanied with optimized treatment of comorbidity when possible.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13054-015-1170-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Epidemiology, Mortality, Myocardial infarction, Shock

Background

Despite considerable improvement in treatment, acute myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of death worldwide [1, 2]. The predominant cause of death in patients hospitalized for MI is cardiogenic shock [3, 4]. The risk of this complication is approximately 5–9 % [3, 5–7]. Subsequent in-hospital mortality is as high as 45–65 % [4, 6], i.e., almost ten times higher than in MI patients without cardiogenic shock [4, 8, 9].

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined as an abrupt decrease in kidney function, ranging from mild kidney dysfunction to severe AKI with need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) [10]. AKI is a complication observed in half of patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock and is associated with a marked elevation of in-hospital mortality risk [11, 12]. In a prospective single-center study, 25 % of cardiogenic shock patients with AKI required dialysis [12], which was associated with an excess in-hospital mortality risk of 16 % compared with patients without need for dialysis (62 % vs. 46 %) [12]. However, the clinical significance of AKI treated with RRT (AKI-RRT) for long-term mortality following MI-related cardiogenic shock and the influence of comorbidity are unknown.

Our aim was to examine the prognostic importance of AKI-RRT with regard to mortality in-hospital and up to 5 years after first-time MI-related cardiogenic shock. Furthermore, we assessed the influence of AKI-RRT in subgroups stratified by comorbid conditions among patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock. Finally, we examined the risk of chronic dialysis after hospitalization with MI-related cardiogenic shock, and we described causes of death among patients surviving the MI-hospitalization.

Methods

Design and setting

We conducted this nationwide population-based cohort study using data from medical registries in Denmark. The Danish National Health Service provides universal tax-supported health care, guaranteeing free access to general practitioners and hospitals, and partial reimbursement of prescribed medications [13]. The unique 10-digit Danish Civil Personal Registry number, assigned to all Danish citizens at birth and to residents upon immigration, allows unambiguous linkage of registries [14].

First-time myocardial infarction patients with cardiogenic shock

We used the Danish National Patient Registry to identify all persons with a first-time admission for MI-related cardiogenic shock from 2005 through 2012. The Danish National Patient Registry contains data on all non-psychiatric hospital admissions since 1977 and on all hospital outpatient specialist clinic and emergency room contacts since 1995 [15]. Each admission is assigned one primary diagnosis code and up to 19 secondary codes classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision (ICD-8) until the end of 1993 and 10th revision (ICD-10) thereafter [15]. Important components of critical care, including dialysis, treatment with inotropes/vasopressors and mechanical ventilation, have been coded routinely with high validity since 2005 [16]. The study cohort included only patients with first-time MI events, i.e., patients without a previous diagnosis of MI since 1977. The cohort was further restricted to MI patients with cardiogenic shock, defined either by a concurrent diagnosis code of cardiogenic shock and/or by medical treatment with inotropes or vasopressors during the MI admission. Patients treated with inotropes or vasopressors, but without a diagnosis code for cardiogenic shock, were excluded if they had a diagnosis code for septic shock, hypovolemic shock, or shock without further specification during the admission. A flowchart of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Additional file 1 (Figure e1). The MI admission period was defined as the initial admission for MI, including transfers to other departments and hospitals.

Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy

Data on any treatment with acute RRT during the hospitalization was obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry, which provides accurate data on treatment with acute RRT [15]. To restrict the cohort to patients with first-time dialysis related to the MI under study, patients with prior RRT treatment for acute or chronic kidney disease were excluded.

Study outcomes

Information on migration and all-cause mortality was obtained through linkage to the Danish Civil Registration System [14]. This registry was established in 1968 and contains information on date of birth, residence, immigration, and vital status, updated daily [14].

We obtained information on causes of death for patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock from the Danish Register of Causes of Death [17]. This registry contains information from all Danish death certificates coded according to the ICD-10 from 1994–2011 [17]. Codes obtained from the Danish Register of Causes of Death are provided in Additional file 1 (Table e1).

We obtained data on date of first chronic dialysis after hospitalization from the Danish National Patient Register [15].

Covariates

The Danish Civil Registration System was used to obtain data on the gender and age of patients [14]. Data on comorbidities were obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry using primary and secondary inpatient diagnoses and outpatient hospital diagnoses during a fixed period of 10 years preceding the current admission for MI. We included comorbidities that could act as potential risk factors for AKI-RRT and have a potential impact on mortality: congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation/flutter, venous thromboembolism, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes, obesity, and cancer. All diagnosis codes used in the study are provided in Additional file 1 (Table e2).

The Danish Health Service Prescription Registry [18] provided information on filled preadmission prescriptions for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin-II antagonists, anti-diabetics, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). We identified prescriptions filled within 100 days before the MI admission because most drugs are sold in packages containing no more than 100 tablets. The Danish Health Service Prescription Registry, established in 2004, includes virtually complete individual-level data on all filled prescriptions for reimbursed drugs in Denmark [18].

We defined diabetes mellitus from its diagnosis code or filled prescriptions for anti-diabetic drugs within 100 days before the MI admission (Additional file 1: Table e2) [18]. Coronary arteriography (CAG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) during admission were identified from procedure codes in the Danish National Patient Registry.

Statistical analyses

We tabulated patient characteristics for the entire study population and for the cohort of patients surviving until hospital discharge (denoted as hospital survivors), including gender, age group, comorbidity, use of medication, and procedures during admission, according to AKI-RRT status.

We first calculated the in-hospital mortality risk in AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients for all patients with complete follow-up on their hospitalization for MI, i.e., patients discharged before the end of the study period on 31 December 2012. Next, we computed the propensity score-adjusted relative risk of death during hospitalization, comparing AKI-RRT patients with non-AKI-RRT patients, using a generalized linear model with a log-link function and a binomial error distribution [19, 20]. We used a propensity score in the adjusted analysis to include more variables than a standard multivariate analysis would allow [21]. The propensity score was defined as the probability of developing AKI-RRT during hospitalization conditioned on the observed baseline covariates and computed using a logistic regression model [21]. The covariates included in the propensity score were gender, age group (<60, 60–69, 70–79, ≥80 years), comorbidities (congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation/flutter, venous thromboembolism, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and obesity), use of medications (ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, NSAIDs), and PCI or CABG status. The equal distribution of propensity scores is visualized in Additional file 1 (Figure e2).

We followed hospital survivors for up to 5 years following their hospital discharge date or until death, emigration, or the end of the study period, whichever came first. We used the 1 minus Kaplan-Meier method to compute cumulative mortality following hospital discharge. Crude and propensity score-adjusted hazard ratios were computed using a Cox regression model. The distribution of propensity scores is shown in Additional file 1 (Figure e3).

To examine the potential differential impact of AKI-RRT within subgroups, we repeated the Cox regression analyses stratified by gender, age groups, comorbidity, PCI or CABG status, and subgroups of MI (ST-elevation MI (STEMI), non-STEMI, and unspecified MI). We adjusted for propensity score. The propensity score calculated within each subgroup included the same baseline variables as in the overall propensity score except for the subgroup variable itself [21].

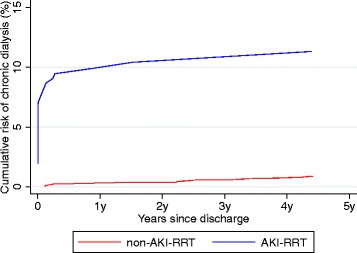

We computed the cumulative risk of chronic dialysis after MI admission by AKI-RRT status accounting for competing risk of death [22]. We visualized the results graphically as a cumulative incidence plot. Crude and propensity score-adjusted hazard ratios were computed with use of a Cox regression model [23].

Proportional hazards assumptions in all of the Cox regression analyses were assessed graphically by plotting log(−log(survival function)) against time for patients with and without AKI-RRT and were found to be satisfactory.

For all MI patients surviving until hospital discharge we tabulated cause of death according to AKI-RRT status. The following causes of immediate death occurred most frequently: cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, pulmonary disease and cancer.

We used STATA statistical software version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA) for all statistical analyses. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, record number 2014-41-3658. Data in the Danish registries are available to researchers, and their use does not require informed consent or ethics approval.

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 5079 patients admitted with MI-related cardiogenic shock. The in-hospital study population consisted of 677 (13 %) patients with AKI-RRT and 4417 (87 %) non-AKI-RRT patients. Patient characteristics for the entire study population are provided in Table 1. Among the 3059 hospital survivors, 254 (8 %) had AKI-RRT during their admission while 2805 (92 %) did not. Patients with AKI-RRT were of similar age as non-AKI-RRT patients and had more comorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the entire study population and of hospital survivors, by AKI-RRT status

| Entire study population | Hospital survivors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical featuresa | Total | No AKI-RRT | AKI-RRT | Total | No AKI-RRT | AKI-RRT |

| n = 5079 (100)b | n = 4417 (100)b | n = 662 (100)b | n = 3059 (100)b | n = 2805 (100)b | n = 254 (100)b | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 3388 (66.7) | 2916 (66.0) | 472 (71.3) | 2164 (70.7) | 1979 (70.6) | 185 (72.8) |

| Female | 1691 (33.3) | 1501 (34.0) | 190 (28.7) | 895 (29.3) | 826 (29.4) | 69 (27.2) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 71 (62–78) | 70 (62–78) | 72 (65–77) | 68 (60–75) | 68 (60–75) | 69 (60–74) |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| < 60 | 1006 (19.8) | 898 (20.3) | 108 (16.3) | 766 (25.0) | 703 (25.1) | 63 (24.8) |

| 60–69 | 1435 (28.3) | 1247 (28.2) | 188 (28.4) | 966 (31.6) | 886 (31.6) | 80 (31.5) |

| 70–79 | 1724 (34.0) | 1440 (32.6) | 284 (42.9) | 989 (32.3) | 899 (32.1) | 90 (35.4) |

| ≥ 80 | 914 (18.0) | 832 (18.8) | 82 (12.4) | 338 (11.1) | 317 (11.3) | 21 (8.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 330 (6.5) | 281 (6.4) | 49 (7.4) | 166 (5.4) | 145 (5.2) | 21 (8.3) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 556 (11.0) | 475 (10.8) | 81 (12.2) | 299 (9.8) | 268 (9.6) | 31 (12.2) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 585 (11.5) | 504 (11.4) | 81 (12.2) | 307 (10.0) | 284 (10.1) | 23 (9.1) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 531 (10.5) | 468 (10.6) | 63 (9.5) | 257 (8.4) | 232 (8.3) | 25 (9.8) |

| Hypertension | 1134 (22.3) | 962 (21.8) | 172 (26.0) | 633 (20.7) | 559 (19.9) | 74 (29.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 393 (7.7) | 342 (7.7) | 51 (7.7) | 185 (6.1) | 166 (5.9) | 19 (7.5) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 79 (1.6) | 69 (1.6) | 10 (1.5) | 36 (1.2) | 31 (1.1) | 5 (2.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 177 (3.5) | 129 (2.9) | 48 (7.3) | 95 (3.1) | 67 (2.4) | 28 (11.0) |

| Liver disease | 55 (1.1) | 49 (1.1) | 6 (0.9) | 21 (0.7) | 19 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) |

| Diabetes mellitusc | 901 (17.7) | 756 (17.1) | 145 (22.0) | 497 (16.3) | 441 (15.7) | 56 (22.1) |

| Cancer | 436 (8.6) | 389 (8.8) | 47 (7.1) | 214 (7.0) | 202 (7.2) | 12 (4.7) |

| Obesity | 143 (2.8) | 116 (2.6) | 27 (4.1) | 81 (2.7) | 70 (2.5) | 11 (4.3) |

| Medication used | ||||||

| ACE inhibitors | 1019 (20.1) | 874 (19.8) | 145 (21.9) | 589 (19.3) | 526 (18.8) | 63 (24.8) |

| Angiotensin II antagonists | 666 (13.1) | 578 (13.1) | 88 (13.2) | 413 (13.5) | 379 (13.5) | 34 (13.4) |

| NSAIDS | 654 (12.9) | 551 (12.5) | 103 (15.6) | 383 (12.5) | 346 (12.3) | 37 (14.6) |

| In-hospital procedures | ||||||

| CAG | 3473 (68.4) | 2979 (67.4) | 494 (74.6) | 2489 (81.4) | 2290 (81.6) | 199 (78.4) |

| PCI | 1873 (36.9) | 1568 (35.5) | 305 (46.1) | 1185 (38.7) | 1065 (38.0) | 120 (47.2) |

| CABG | 1520 (29.9) | 1334 (30.2) | 186 (28.1) | 1334 (43.6) | 1251 (44.6) | 82 (32.7) |

a Comorbidities registered as primary or secondary hospital inpatient and outpatient diagnoses within 10 years preceding current admission

b Values are expressed as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated

c Defined as either a diagnosis code for diabetes or a prescription redemption for anti-diabetics within 100 days before MI admission

d Prescription redemption within 100 days before admission

ACE Angiotensin-converting enzyme, AKI-RRT Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, CAG Coronary arteriography, IQR inter quartile range, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, PCI percutaneous coronary arteriography

Mortality

Among 677 patients with AKI-RRT, 408 died during admission, yielding an in-hospital mortality of 62 %, while 1612 out of 4417 patients without AKI-RRT died during admission, yielding an in-hospital mortality of 36 %. The corresponding propensity score-adjusted relative risk of in-hospital death was 1.70 (95 % confidence interval (CI): 1.59–1.81) for patients with AKI-RRT compared with non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

In-hospital mortality by AKI-RRT status

| Exposure | No. of deaths | No. of hospitalized patientsa | Absolute mortality risk (95 % CI) | Relative risk (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (95 % CI) | Adjustedb (95 % CI) | ||||

| No AKI-RRT | 1612 | 4417 | 36 % (35–38) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| AKI-RRT | 408 | 662 | 60 % (56–64) | 1.69 (1.57–1.81) | 1.70 (1.59–1.81) |

a Patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock

b Adjusted using a propensity score based on sex, age group, and presence/absence of congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation/flutter, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, cancer, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II antagonists, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery bypass graft status

AKI-RRT Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy, CI confidence interval

Total follow-up time for hospital survivors was 8838 person-years. Six patients without AKI-RRT emigrated during follow-up. AKI-RRT patients had a median follow-up time of 2.2 years (interquartile range (IQR): 0.9–4.6 years) and non-AKI-RRT patients had a median follow-up time of 3.0 years (IQR: 1.2–5.2 years).

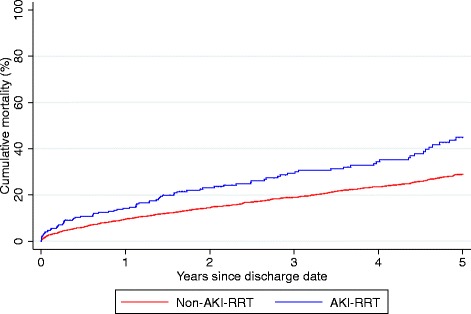

For patients with AKI-RRT, the mortality risks within 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years after discharge were 5 %, 14 %, and 45 %, respectively. For patients without AKI-RRT the corresponding mortality risks were 3 %, 10 %, and 29 % (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The propensity score-adjusted hazard ratio for death within 5 years after discharge was 1.55 (95 % CI: 1.22–1.96) for patients with AKI-RRT compared with non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Five-year mortality estimates for patients with and without AKI-RRT following first-time hospital admission with myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock

| Exposure | No. of deaths | No. of hospital survivorsa | Cumulative mortality % (95 % CI) | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day | 1-year | 5-year | Crude | Adjustedb | |||

| No AKI-RRT | 589 | 2805 | 2.5 (2.0–3.2) | 9.6 (8.5–10.8) | 28.9 (26.8–31.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| AKI-RRT | 81 | 254 | 4.7 (2.7–8.2) | 14.2 (10.4–19.3) | 44.9 (37.2–53.4) | 1.67 (1.32–2.11) | 1.55 (1.22–1.96) |

a Patients surviving until hospital discharge

b Cox proportional hazards regression model adjusted using a propensity score

AKI-RRT Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy, CI confidence intervals

Fig. 1.

Five-year cumulative mortality by acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) status

The association between AKI-RRT and mortality differed by gender. Among males, AKI-RRT increased the 5-year mortality risk after 5 years from 26 % to 45 %, with a corresponding propensity score-adjusted hazard ratio of 1.85 (95 % CI: 1.41–2.43) (Table 4). Among females, AKI-RRT increased the 5-year mortality risk from 35 % to 45 %, with a corresponding 5-year propensity score-adjusted hazard ratio of 1.04 (95 % CI: 0.64–1.68) (Table 4). Non-AKI-RRT patients with comorbidity had a higher absolute mortality risk compared to non-AKI-RRT patients without comorbidity (Table 4). Despite high mortality in AKI-RRT patients, the relative importance of AKI-RRT for 5-year mortality was thereby attenuated among patients with comorbidities (Table 4). This was most predominant in patients with chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, liver disease, and patients who did not undergo CAG, PCI, or CABG (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of 5-year cumulative mortality following first-time admission with myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock comparing patients with and without AKI-RRT

| Exposure | No. of deaths | No. of hospital survivorsa | No AKI-RRT 5-year risk % (95 % CI) |

AKI-RTT 5-year risk % (95 % CI) |

Hazard ratiob

(95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 479 | 2164 | 26.3 (24.0–28.9) | 44.7 (36.1–54.3) | 1.85 (1.41–2.43) |

| Female | 264 | 895 | 34.9 (31.0–39.1) | 45.3 (30.2–63.7) | 1.04 (0.64–1.68) |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| <60 | 80 | 766 | 12.1 (9.3–15.5) | 32.4 (20.0–49.8) | 3.00 (1.67–5.40) |

| 60–69 | 185 | 966 | 23.0 (19.8–26.6) | 30.1 (20.5–44.7) | 1.24 (0.76–2.02) |

| 70–79 | 309 | 989 | 37.1 (33.2–41.3) | 60.6 (45.5–76.1) | 1.47 (0.82–2.57) |

| ≥ 80 | 169 | 338 | 58.7 (51.7–65.7) | 77.6 (51.9–95.3) | 1.45 (0.82–2.57) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | |||||

| No | 658 | 2893 | 27.0 (24.9–29.2) | 43.2 (35.2–52.1) | 1.64 (1.28–2.11) |

| Yes | 85 | 166 | 62.9 (52.9–73.0) | 62.3 (36.6–87.6) | 0.67 (0.33–1.25) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |||||

| No | 613 | 2760 | 26.4 (24.3–28.7) | 43.5 (25.2–52.7) | 1.69 (1.31–2.19) |

| Yes | 130 | 299 | 52.5 (44.9–60.4) | 55.8 (36.2–77.3) | 1.11 (0.33–1.35) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||||

| No | 631 | 2752 | 26.8 (24.7–29.1) | 42.8 (34.8–51.7) | 1.54 (1.20–1.98) |

| Yes | 112 | 307 | 50.0 (42.0–58.7) | 60.9 (39.6–82.6) | 2.23 (1.16–4.28) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | |||||

| No | 632 | 2802 | 26.6 (24.5–28.8) | 46.1 (37.9–55.1) | 1.86 (1.45–2.28) |

| Yes | 111 | 257 | 52.7 (45.1–60.7) | 33.4 (17.3–58.1) | 0.56 (0.26–1.21) |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 668 | 2874 | 27.8 (25.7–30.0) | 42.5 (34.6–51.4) | 1.76 (1.33–2.32) |

| Yes | 75 | 185 | 47.8 (38.2–58.3) | 68.4 (43.5–90.3) | 1.18 (0.77–1.80) |

| Atrial fibrillation | |||||

| No | 629 | 2938 | 28.1 (26.1–30.4) | 44.4 (36.7–52.9) | 1.56 (1.21–2.01) |

| Yes | 74 | 195 | 50.1 (40.7–60.3) | 70.0 (45.5–90.7) | 1.53 (0.79–2.98) |

| VTE | |||||

| No | 726 | 3023 | 28.7 (26.6–30.8) | 45.2 (37.3–53.8) | 1.60 (1.26–2.03) |

| Yes | 17 | 36 | 46.8 (30.1–67.2) | 40.0 (11.8–87.4) | 1.22 (0.27–5.46) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||

| No | 694 | 2964 | 28.0 (25.9–30.2) | 41.9 (34.0–50.8) | 1.60 (1.24–2.06) |

| Yes | 49 | 95 | 67.9 (53.7–81.3) | 75.5 (48.5–95.0) | 0.94 (0.49–1.79) |

| Liver disease | |||||

| No | 729 | 3038 | 28.6 (26.5–30.8) | 44.6 (36.9–53.2) | 1.60 (1.26–2.03) |

| Yes | 14 | 21 | 70.2 (45.3–91.2) | – | 0.73 (0.08–6.48) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 590 | 2562 | 26.8 (24.6–29.1) | 42.2 (33.9–51.5) | 1.71 (1.31–2.24) |

| Yes | 153 | 497 | 41.6 (35.6–48.3) | 58.0 (38.7–78.5) | 1.22 (0.75–1.99) |

| Cancer | |||||

| No | 661 | 2845 | 27.5 (25.4–29.7) | 44.7 (36.8–53.5) | 1.62 (1.27–2.07) |

| Yes | 82 | 214 | 47.2 (38.8–56.5) | 49.2 (23.4–82.2) | 1.03 (0.41–2.58) |

| Obesity | |||||

| No | 724 | 2978 | 28.8 (26.7–31.0) | 44.7 (36.9–53.3) | 1.60 (1.26–2.03) |

| Yes | 19 | 81 | 31.7 (19.9–48.0) | 60.2 (17.9–98.7) | 1.19 (0.33–4.28) |

| In-hospital procedures | |||||

| No CAG, PCI or CABG | 264 | 481 | 63.1 (57.5–68.6) | 51.3 (36.7–67.8) | 0.71 (1.26–2.03) |

| PCI | 220 | 1185 | 22.7 (19.7–26.2) | 46.8 (35.7–60.8) | 2.26 (1.57–3.25) |

| CABG | 217 | 1334 | 17.5 (15.0–20.2) | 37.7 (25.8–52.7) | 2.18 (1.38–3.44) |

| MI subgroups | |||||

| STEMI | 252 | 1199 | 25.8 (22.6–29.3) | 39.8 (29.3–52.4) | 1.70 (1.17–2.47) |

| Non-STEMI | 282 | 1138 | 29.2 (26.0–37.8) | 47.9 (30.9–68.3) | 1.74 (1.07–2.83) |

| MI unspecified | 209 | 722 | 33.5 (29.2–38.3) | 48.7 (36.0–63.1) | 1.27 (0.84–1.91) |

a Patients surviving until hospital discharge

b Adjusted for propensity score; the propensity score was calculated within each subgroup including the same baseline variables as in the overall propensity score except for the subgroup variable itself. The hazard ratio is based on AKI-RRT patients compared with non-AKI-RRT patients

AKI acute kidney injury, AKI-RRT Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy, CABG coronary arterial bypass graft, CAG coronary angiography, CI confidence interval, MI myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, STEMI ST-elevation myocardial infarction, VTE venous thromboembolism

AKI-RRT patients with STEMI and non-STEMI had a 5-year risk of death of 40 % and 48 %, respectively. The propensity score-adjusted hazard ratios did not differ between STEMI (1.70 (95 % CI: 1.17–2.47) and non-STEMI (1.74 (95 % CI: 1.07–2.83)) (Table 4).

Cardiovascular diseases were leading causes of death among patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock (61 % of causes for AKI-RRT patients and 51 % for non-AKI-RRT patients) (Table 5). Myocardial infarction and chronic ischemic heart disease were the most influential individual causes of death comprising each around 20 % for AKI-RRT patients and 15 % for non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 5). Chronic kidney disease as cause of death accounted for 5 % for AKI-RRT patients and 2 % for non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cause of death among 573 patients dying during follow-up after admission with myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock, by AKI-RRT status

| Cause of death (immediate) | Total n = 573 (100)a |

No AKI-RRT n = 512 (100)a |

AKI-RRT n = 61 (100)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 297 (51.8) | 260 (50.8) | 37 (60.7) |

| Chronic ischemic disease | 23 (4.0) | 19 (3.7) | 4 (6.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 88 (15.4) | 76 (14.8) | 12 (19.7) |

| Chronic ischemic heart disease | 93 (16.2) | 82 (16.0) | 11 (18.0) |

| Stroke, ischemic | 21 (3.7) | 19 (3.7) | 2 (3.3) |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 72 (12.5) | 64 (12.5) | 8 (13.1) |

| Kidney disease | 13 (2.3) | 9 (1.8) | 4 (6.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12 (2.1) | 9 (1.8) | 3 (4.9) |

| Chronic dialysis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other kidney disease | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) |

| Pulmonary disease | 54 (9.4) | 47 (9.2) | 7 (11.5) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 37 (6.5) | 31 (6.1) | 6 (9.8) |

| Pneumonia | 10 (1.8) | 9 (1.8) | 1 (1.6) |

| Other respiratory disease | 7 (1.2) | 7 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Cancer | 75 (13.1) | 73 (14.3) | 2 (3.3) |

| Other cause of death | 134 (23.4) | 123 (24.0) | 11 (18.0) |

a Values are expressed as number (percentage)

AKI-RRT Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy, CI confidence interval

Need for chronic dialysis

The 5-year cumulative risk of chronic dialysis after admission with MI-related cardiogenic shock for AKI-RRT patients was 11.3 % (95 % CI: 7.6–15.9 %) compared with 0.9 % (95 % CI: 0.5–1.4 %) for non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 6 and Fig. 2). The propensity score-adjusted hazard ratio for need of chronic dialysis after MI-related cardiogenic shock was 15.9 (95 % CI: 8.7–29.3) for AKI-RRT patients compared with non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 6).

Table 6.

Need for chronic dialysis for patients with and without AKI-RRT in 5 years following first-time hospital admission with MI-related cardiogenic shock

| Exposure | Chronic dialysis | No. of hospital survivorsa | Cumulative mortality % (95 % CI) | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjustedb | ||||

| No AKI-RRT | 18 | 2,805 | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| AKI-RRT | 27 | 254 | 11.3 (7.6–15.9) | 18.7 (10.3–33.9) | 15.9 (8.7–29.3) |

a Patients surviving until hospital discharge

b Cox proportional hazards regression model adjusted using a propensity score

AKI-RRT Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy, CI confidence intervals, MI myocardial infarction

Fig. 2.

Five-year cumulative risk of chronic dialysis by acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) status

Discussion

This study demonstrated an almost twofold increase in in-hospital mortality in cardiogenic shock patients with AKI-RRT compared with non-AKI-RRT patients. While no previous studies examined the prognostic impact after hospital discharge, we found an approximate 50 % increased mortality up to 5 years after discharge. The relative impact of AKI-RRT was most pronounced among younger patients without comorbidity, a finding possibly explained by the lower absolute mortality in this subgroup of patients. We found the presence of comorbidities itself to be associated with a poor prognosis.

AKI-RRT increased the risk of chronic dialysis almost 16 times compared with non-AKI-RRT patients during the 5-year follow-up and may contribute to the increased long-term mortality among AKI-RRT patients. In addition, three times as many AKI-RRT patients were registered with chronic kidney disease as the cause of death compared with non-AKI-RRT patients.

Not surprisingly, cardiovascular disease explained the majority of deaths among patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock.

Existing studies

Consistent with our findings, two previous studies [11, 12] reported markedly increased in-hospital mortality among cardiogenic shock patients with AKI compared with cardiogenic shock patients without AKI. In a cohort study of 97 patients hospitalized with STEMI and cardiogenic shock, 52 patients (55 %) developed AKI (defined as a 25 % rise in serum creatinine from baseline) [12]. Thirteen of the 52 patients with AKI (25 %) required dialysis. In-hospital mortality risk increased with rising AKI severity from 2 % among patients without AKI, to 46 % among patients with non-AKI-RRT, and to 62 % among patients with AKI-RRT [12]. In contrast to our study of patient data from all Danish hospitals, that study consisted of a study population admitted to an intensive care unit at a University Cardiology Center in Italy. No clear international recommendation exists for initiation of RRT [10], which may explain the difference in AKI-RRT prevalence (25 % compared with 13 % in our study).

Another study of 118 patients with cardiogenic shock following acute coronary syndrome between 1993 and 2000 revealed an AKI risk of 33 %, with an in-hospital mortality risk of 87 % among patients with AKI and 53 % among patients without AKI [11]. AKI thus remains a serious complication of cardiogenic shock, with poor in-hospital outcome despite aggressive interventional reperfusion treatments.

Cardiogenic shock has been reported as a complication in 5–10 % of STEMI cases and in 2–4 % of non-STEMI cases [24, 25]. Nevertheless, non-STEMI complicated with cardiogenic shock has been reported to be associated with higher in-hospital mortality than STEMI complicated with cardiogenic shock [25], presumably due to more comorbidity [26] and more severe coronary artery disease [27]. We did not find any differences in the impact of AKI-RRT on long-term mortality between subgroups of patients with non-STEMI and STEMI among MI patients with cardiogenic shock.

Another Danish cohort study examined the risk of end-stage renal disease after dialysis-requiring AKI among 107,937 patients admitted to an intensive care unit [28]. Consistent with our results, the cumulative risk of chronic dialysis in the study was 8.5 % 91–180 days after admission and 3.8 % 181 days to 5 years after admission for dialysis-requiring AKI patients [28]. For patients without dialysis-requiring AKI, the cumulative risk of chronic dialysis was 0.1 % 91–180 days after admission and 0.3 % 181 days to 5 years after admission [28].

Potential mechanisms

The mechanisms underlying our findings are not well understood. Cardiorenal crosstalk in acute MI involves multifactorial systems and has recently been classified as a cardiorenal syndrome type 1 [29]. Classical mechanisms include low cardiac output and neurohormonal activation, release of vasoactive substances resulting in low renal perfusion, and possible renal ischemia with AKI [29]. In addition, a marked alteration of immune and somatic cell signaling has been implicated as an important contributor to kidney injury [29].

Coronary intervention was frequent in our population, so the potential for contrast-induced AKI-RRT must be considered in some patients [30]. Moreover, cardiac surgery is a known risk factor for development of AKI among CABG patients [31, 32].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are its nationwide population-based cohort design with a well-defined study population in a country providing tax-financed universal healthcare. This design minimizes selection bias. In addition, follow-up for mortality was virtually complete.

The positive predictive value of MI as a primary diagnosis in the Danish National Patient Registry is 94 % [33], and the positive predictive value of cardiogenic shock in the Danish National Patient Registry was found to be equally high in a validation study [34]. In this study, we included treatment with inotropes/vasopressors that we expect to be a valid proxy for shock. As the positive predictive value of acute dialysis is 98 % [16], we assume that the potential for information bias was small. Any such information bias is expected to be caused by non-differential misclassification, because registration of AKI-RRT is unlikely to be dependent on mortality status and vice versa. Non-differential misclassification would have biased the association towards the null [35].

A study limitation was lack of creatinine measurements. Consequently, we could only discriminate between patients with and without the most severe form of AKI, namely AKI-RRT.

We have no information about the initiation of RRT relative to the AKI onset. Delayed initiation of RRT may be associated with increased mortality among AKI patients [36], and might have affected our results.

Availability and validity of variables to measure potential confounding factors are crucial, and unmeasured and residual confounding must be considered. In observational studies the impact of uncontrolled confounding is a major concern [37]. Since the propensity score method and multivariate adjustment only include known confounders, the potential for some unmeasured confounding exists. In this study we had no information on smoking [38], and the potential for residual confounding exists for the registration of comorbidities, e.g. hypertension.

Heart failure has an impact on long-term-mortality risk after MI [39, 40], but we lacked data to examine whether the impact of AKI was influenced by reduced left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge. However, even if the data were available, it would be inappropriate to adjust for a factor in the causal pathway between AKI-RRT and mortality.

A high absolute mortality risk was seen for subgroups of patients with chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and liver disease, and those who did not undergo CAG, PCI, or CABG, independent of AKI-RRT status. Clinical guidelines recommend that all patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock are treated with either PCI or CABG, if the patient is considered suitable for the procedure [41, 42]. A potential for confounding by indication is apparent in this setting when the most severely affected patients with comorbid diseases are not offered dialysis or PCI/CABG due to their expected high mortality.

Since registration of causes of death is based on subjective clinical judgment and first-time and recurrent MI may to some extent overlap, caution is warranted in the interpretation of cause of death data.

Clinical significance

AKI-RRT is an important clinical predictor of elevated in-hospital and long-term mortality among patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock. Potential causes of increased mortality may be increased risk of end-stage renal disease [28] and/or cardiovascular disease [43]. However, more studies are needed to further examine the cause of increased long-term mortality, e.g., increased risk of a second cardiovascular event.

Conclusion

In a large population-based setting, this study found that AKI-RRT was associated with a substantially increased in-hospital mortality, 5-year risk of chronic dialysis, and 5-year mortality. While, comorbidity increased the absolute mortality risk for all MI patients with cardiogenic shock, the relative effect of AKI-RRT for 5-year mortality was most pronounced among patients without comorbidity.

Key messages

Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) is an important predictor of elevated in-hospital and long-term mortality among patients with MI-related cardiogenic shock.

AKI-RRT is associated with substantially increased risk of chronic dialysis.

In patients with comorbidity, absolute mortality increased while relative impact of AKI-RRT on mortality decreased.

Future studies are needed to examine the cause of increased long-term mortality, e.g., increased risk of a second cardiovascular event.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences (FSS) (DFF – 1333–00014), the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure (PROCRIN) established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Aarhus University Research Foundation, Oticon Foundation, and Master cabinetmaker Sophus Jacobsen and Wife Astrid Jacobsen Foundation. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of the study.

Abbreviations

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- AKI-RRT

Acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

- CAG

Coronary arteriography

- CI

Confidence interval

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- RRT

Renal replacement therapy

- STEMI

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Additional file

Flowchart of study population. Figure e2. Distribution of propensity scores for the entire study population. Figure e3. Distribution of propensity scores for the cohort of patients surviving until hospital discharge. Table e1. Codes used to identify the study population, comorbidity, use of medicine, and in-hospital procedures. Table e2. Causes of immediate death. (PDF 194 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors had access to the data, and have all seen and approved the manuscript and have contributed significantly to the work. MDL, HG, MS, and CFC conceived of the study idea and designed the study. TBR collected the data. MDL, HG, MS, RES, HEB, HTS, and CFC reviewed the literature. MDL, HG and TBR performed the statistical analyses. MDL organized the writing, and wrote the initial draft. All authors participated in the discussion and interpretation of the results, critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the final version before submission. CFC is the guarantor.

Contributor Information

Marie Dam Lauridsen, Phone: +45 8716 8063, Email: mala_mdl@hotmail.com.

Henrik Gammelager, Email: hg@clin.au.dk.

Morten Schmidt, Email: morten.schmidt@clin.au.dk.

Thomas Bøjer Rasmussen, Email: tbr@clin.au.dk.

Richard E. Shaw, Email: ShawR@sutterhealth.org

Hans Erik Bøtker, Email: heb@dadlnet.dk.

Henrik Toft Sørensen, Email: hts@clin.au.dk.

Christian Fynbo Christiansen, Email: cfc@clin.au.dk.

References

- 1.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Lash TL, Botker HE, Sorensen HT. 25 year trends in first time hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, subsequent short and long term mortality, and the prognostic impact of sex and comorbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubey L, Sharma S, Gautam M, Gautam S, Guruprasad S, Subramanyam G. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction—a review. Acta Cardiol. 2011;66(6):691–9. doi: 10.1080/ac.66.6.2136951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation. 2009;119(9):1211–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation. 2008;117(5):686–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babaev A, Frederick PD, Pasta DJ, Every N, Sichrovsky T, Hochman JS, et al. Trends in management and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA. 2005;294(4):448–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awad HH, Anderson FA, Jr, Gore JM, Goodman SG, Goldberg RJ. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute coronary syndromes: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):963–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang J, Mensah GA, Alderman MH, Croft JB. Trends in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock, 1979–2003, United States. Am Heart J. 2006;152(6):1035–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.OECD . Health at a Glance: Europe 2012. 2. Washington DC: OECD; 2012. In-hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction; pp. 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO%20AKI%20Guideline.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed 15 Nov 2013.

- 11.Koreny M, Delle Karth G, Geppert A, Neunteufl T, Priglinger U, Heinz G, et al. Prognosis of patients who develop acute renal failure during the first 24 hours of cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2002;112(2):115–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)01070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, De Metrio M, Lauri G, Marana I, et al. Acute kidney injury in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock at admission. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):438–44. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9eb3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National board of health. Health care in Denmark. http://tyskland.um.dk/de/~/media/Tyskland/Germansite/Documents/Reise%20und%20Aufenthalt/Health%20Care%20in%20Denmark.pdf. Accessed 24 Dec 2015.

- 14.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt M, Schmidt S, Sandegaard J. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–90. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blichert-Hansen L, Nielsson MS, Nielsen RB, Christiansen CF, Norgaard M. Validity of the coding for intensive care admission, mechanical ventilation, and acute dialysis in the Danish National Patient Registry: a short report. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:9–12. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):26–9. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannesdottir SA, Horvath-Puho E, Ehrenstein V, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish national database of reimbursed prescriptions. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:303–13. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wacholder S. Binomial regression in GLIM: estimating risk ratios and risk differences. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123(1):174–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindquist K. Stata FAQ. How can I estimate relative risk using glm for common outcomes in cohort studies? UCLA: Statistical consulting group. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/faq/relative_risk.htm. Accessed April 2014.

- 21.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coviello V. Cumulative incidence estimation in the presence of competing risks. Stata J. 2004;4(2):103. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):861–70. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westaby S, Kharbanda R, Banning AP. Cardiogenic shock in ACS. Part 1: prediction, presentation and medical therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;9(3):158–71. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson ML, Peterson ED, Peng SA, Wang TY, Ohman EM, Bhatt DL, et al. Differences in the profile, treatment, and prognosis of patients with cardiogenic shock by myocardial infarction classification: a report from NCDR. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(6):708–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terkelsen CJ, Lassen JF, Norgaard BL, Gerdes JC, Jensen T, Gotzsche LB, et al. Mortality rates in patients with ST-elevation vs. non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: observations from an unselected cohort. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(1):18–26. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg RJ, Steg PG, Sadiq I, Granger CB, Jackson EA, Budaj A, et al. Extent of, and factors associated with, delay to hospital presentation in patients with acute coronary disease (the GRACE registry) Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(7):791–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gammelager H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, Tonnesen E, Jespersen B, Sorensen HT. Five-year risk of end-stage renal disease among intensive care patients surviving dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury: a nationwide cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17(4):R145. doi: 10.1186/cc12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haase M, Muller C, Damman K, Murray PT, Kellum JA, Ronco C, et al. Pathogenesis of cardiorenal syndrome type 1 in acute decompensated heart failure: workgroup statements from the eleventh consensus conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Contrib Nephrol. 2013;182:99–116. doi: 10.1159/000349969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tehrani S, Laing C, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury following PCI. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43(5):483–90. doi: 10.1111/eci.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen MK, Gammelager H, Mikkelsen MM, Hjortdal VE, Layton JB, Johnsen SP, et al. Post-operative acute kidney injury and five-year risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke among elective cardiac surgical patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):R292. doi: 10.1186/cc13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert AM, Kramer RS, Dacey LJ, Charlesworth DC, Leavitt BJ, Helm RE, et al. Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a comparison of two consensus criteria. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(6):1939–43. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madsen M, Davidsen M, Rasmussen S, Abildstrom SZ, Osler M. The validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in routine statistics: a comparison of mortality and hospital discharge data with the Danish MONICA registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(2):124–30. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauridsen M, Gammelager H, Schmidt M, Nielsen H, Christiansen C. Positive predictive value of International Classification of Disease, 10th revision, diagnosis code for cardiogenic, hypovolemic, and septic shock in the Danish National Patient Registry. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology. An introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seabra VF, Balk EM, Liangos O, Sosa MA, Cendoroglo M, Jaber BL. Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation in acute renal failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):272–84. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorensen HT, Lash TL, Rothman KJ. Beyond randomized controlled trials: a critical comparison of trials with nonrandomized studies. Hepatology. 2006;44(5):1075–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.21404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Himbert D, Golmard JL, Juliard JM, Feldman LJ, Steg PG. Impact of smoking on the incidence and survival of cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction treated with reperfusion therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(1):73–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksson SV, Caidahl K, Hamsten A, de Faire U, Rehnqvist N, Lindvall K. Long-term prognostic significance of M mode echocardiography in young men after myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995;74(2):124–30. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng VG, Lansky AJ, Meller S, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, et al. The prognostic importance of left ventricular function in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2014;3(1):67–77. doi: 10.1177/2048872613507149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(4):529–55. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, Califf RM, Cheitlin MD, Hochman JS, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary and recommendations. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (committee on the management of patients with unstable angina) Circulation. 2000;102(10):1193–209. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.10.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drakos SG, Bonios MJ, Anastasiou-Nana MI, Tsagalou EP, Terrovitis JV, Kaldara E, et al. Long-term survival and outcomes after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(8):E4–8. doi: 10.1002/clc.20488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]