Abstract

Context

Several widely held beliefs about child abuse and neglect may be incorrect. It is most commonly assumed that some forms of abuse (e.g., physical and sexual abuse) are more harmful than others (e.g., emotional abuse and neglect); other assumptions are that each form of abuse has specific consequences, and that the effects of abuse differ across sex and race.

Objective

To determine whether these assumptions are valid by testing the hypothesis that different types of child maltreatment actually have equivalent, broad, and universal effects.

Design

Large, diverse sample collected over 27 years.

Setting

Research summer camp program for low-income, school-aged children.

Participants

Participants were 2,292 racially and ethnically diverse boys (55%) and girls (45%), aged 5–13 years. Of these, 1,193 (52%) had a well-documented history of child maltreatment.

Main Outcome Measures

Various forms of internalizing and externalizing personality and psychopathology were assessed using multiple informant ratings on the California Child Q-set and Teacher Report Form, as well as child self-reported depression and peer ratings of aggression and disruptive behavior.

Results

Using a structural analysis, we found that different forms of child maltreatment have equivalent psychiatric effects. We also found that maltreatment alters two broad vulnerability factors, Internalizing (β = .185, p < .001) and Externalizing (β = .283, p < .001), that underlie multiple forms of psychiatric disturbance, and that maltreatment has equal consequences for boys and girls of different races. Finally, our results allowed us to describe a base rate and co-occurrence issue that makes it difficult to identify the unique effects of child sexual abuse.

Conclusions

Our findings challenge widely held beliefs about how child abuse should be recognized and treated—a responsibility that often lies with the clinician. Because different types of child abuse have equivalent, broad, and universal effects, effective treatments for maltreatment of any sort are likely to have comprehensive psychological benefits. Population-level prevention and intervention strategies should emphasize emotional abuse, a widespread cruelty far less punishable than other types of child maltreatment.

Worldwide prevalence estimates suggest that child physical abuse (8.0%), sexual abuse (1.6%), emotional abuse (36.3%), and neglect (4.4%) are common cruelties.1,2 These forms of abuse and neglect are collectively referred to as child maltreatment (CM). At least four assumptions pervade the scientific literature on CM: 1. harmfulness, CM causes substantial harm; 2. non-equivalence, some forms of CM are more harmful than others; 3. specificity, each form of CM has specific consequences; and 4. non-universality, the effects of CM differ across sex and race.

The strongest assumption is that CM causes harm. In a meta-analysis, non-sexual forms of CM (physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect) were associated with a wide range of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance use, and suicidal behavior.3 Evidence from research on sexual abuse is less consistent. Although early literature reviews concluded that child sexual abuse predicts a range of psychiatric outcomes,4–6 more recent meta-analyses based on community samples7 and college samples8 suggest that child sexual abuse is weakly associated with later adjustment problems. Unsurprisingly, these findings are controversial9, and have been criticized10,11 and defended12,13 on several occasions.

The non-equivalence assumption is evident in the legal system, where some forms of CM are felonies but others are legal, and in the scientific literature, which focuses predominantly on sexual and physical abuse.14 However, meta-analytic data do not show appreciable differences in harm across types of CM.3 Furthermore, study-level comparisons are confounded by differences in samples and methods, and individual-level comparisons are rare and usually fail to model patterns of CM co-occurrence. The ubiquity of the non-equivalence assumption must therefore be based on factors other than comparative evidence of harm, such as cultural mores and differences in the ability to measure and document maltreatment.

The specificity assumption is based on early studies suggesting that particular exposures may be linked to particular mental health outcomes.15,16 However, subsequent evidence suggests that various forms of CM may have non-specific, widespread effects on mental health.13,16,17 An unanswered question is whether such widespread effects are the result of CM affecting common factors that underlie multiple psychiatric disorders.

The non-universality assumption has received occasional support from research showing sex differences18 and racial differences19 in CM-related outcomes, motivating some to recommend treatments tailored to sex and race.21 However, research in this area is scarce and few studies have directly (statistically) tested sex or race as a moderator. Prevalence rates may differ between populations, as might various risk factors and service response variables, but the question of whether the effects of CM generalize across populations remains unanswered.

To test each assumption and overcome the limitations of previous research, this study rigorously assesses multiple forms of CM, relates them structurally, and uses them to predict a broad range of ensuing maladjustment in a large, racially diverse sample of boys and girls aggregated over 27 years. We hypothesize that our results will correspond to meta-analytic evidence supporting the assumption of harm; otherwise, our results will contradict the other assumptions, including non-equivalence, specificity, and non-universality. That is, we hypothesize that different forms of CM will have equivalent, broad, and universal consequences. Such findings would have substantial etiological, clinical, and legal implications.

Method

Participants

The participants in this investigation included 2,292 children aged 5 to 13 (M=9.05, SD=2.04) who attended a summer camp research program designed for school-aged low income children. Data were collected each year from 1986 to 2012. Some children attended the camp for multiple years, and the data from their first year of attendance were used in the current study. The study design specified recruitment of both maltreated children (n=1193) and nonmaltreated children (n=1099). Among the participants, 54.7% were boys. The maltreated and nonmaltreated children were comparable in terms of racial/ethnic diversity and family demographic characteristics22. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health system for coding race and ethnicity was used.23 The sample was 60.4% African American (5.3% Hispanic), 31.0% White (36.8% Hispanic), and 8.6% from other racial groups (3.2% Hispanic). The families of the children were low income, with 95.1% of the families having a history of receiving public assistance. Single mothers headed 62.9% of the families.

Recruitment, Classification of CM, and Procedure

This research was reviewed and approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board. Full details regarding the recruitment of participants, classification of CM, and study procedure are provided in the Supplement. Briefly, parents of all maltreated and nonmaltreated children provided informed consent for their child’s participation, as well as consent for examination of any Department of Human Services (DHS) records pertaining to the family. Comprehensive searches of DHS records were completed, and maltreatment information was coded utilizing operational criteria from maltreatment nosology specified in the Maltreatment Classification System (MCS24). The whole sample was representative of the children in families receiving services from the DHS.

Consistent with national demographic characteristics of maltreating families,25 the maltreated children were predominantly from low-SES families. Consequently, demographically comparable nonmaltreated children were recruited from families receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. To verify the absence of child maltreatment in these families, DHS records were searched, mothers were interviewed using the Maternal Maltreatment Classification Interview,26 and record searches were conducted in the year following camp attendance to verify that all available information had been accessed. Only children from families without any history of documented abuse or neglect were retained in the nonmaltreatment group.

The MCS is a reliable and valid method for classifying maltreatment that utilizes DHS records detailing investigations and findings involving maltreatment in identified families over time. Rather than relying on official designations and case dispositions, the MCS codes all available information from DHS records, making independent determinations of maltreatment experiences. Coding of the DHS records was conducted by trained raters who demonstrated acceptable reliability with the criterion (weighted kappas with the criterion ranging from 0.86 to 0.98). Reliabilities for the presence versus absence of maltreatment subtypes ranged from 0.90 to 1.00.

Children attended a week-long day camp program, where they were assigned to groups of eight to ten same-age and same-sex peers; half of the children assigned to each group were maltreated.27 Each group was conducted by three trained camp counselors, who were unaware of the maltreatment status of children and the hypotheses of the study. Over the week, camp provided 35 hours of interaction between children and counselors. In addition to the recreational activities, after providing assent, children participated in various research assessments. Clinical consultation and intervention occurred if any concerns over danger to self or others emerged during research sessions. At the end of the week, children in each group completed sociometric ratings of their peers. The counselors, who had been trained extensively for 2 weeks prior to the camp, also completed assessment measures on individual children, based on their observations and interactions with children in their respective groups.

Measures

The camp context and associated measurement battery provided a multiple-informant view of child adaptive functioning. Measures included child self-report, peer nominations, and counselor-reports. These measures provided emotional, behavioral, and temperament indicators of the internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) spectra, the two broad factors that underlie common psychiatric disorders.28

Child report

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI29) is a widely used self-report questionnaire to assess depressive symptomatology in school-age children. Internal consistency for the total scale has ranged from 0.71 to 0.89, and validity has been well established.29 In the current sample, scores on the CDI ranged from 0 to 42 (M=8.93, SD=7.51).

Peer reports

On the last day of summer camp, children evaluated the characteristics of their peers in their respective camp groups. Children were given behavioral descriptors characterizing different types of social behavior and asked to select one peer from the group who best fit the behavioral description. Descriptors included a child who was disruptive, and a child who was a fighter. The total number of nominations that each individual child received from peers in both categories was determined, and these totals were converted to proportions of the possible nominations in each category. Scores in each category were standardized within each year of camp.

Counselor reports

Behavioral symptomatology was evaluated at the end of each week by counselors’ completion of the Teacher Report Form (TRF)30 and the California Child Q-set (CCQ).31 The TRF is a widely used and validated instrument to assess child symptomology from the perspective of teachers; the TRF was used in the present study because camp counselors are able to observe similar behaviors to that of teachers. The CCQ consists of statements about traits that represent major facets of personality, including those from the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality. Counselors’ scores on the TRF and CCQ were averaged to obtain individual child scores. Interrater reliability across all scales, based on average intraclass correlations among pairs of raters, ranged from 0.56 to 0.88 (M=0.76).

Results

Subgroup Comparisons

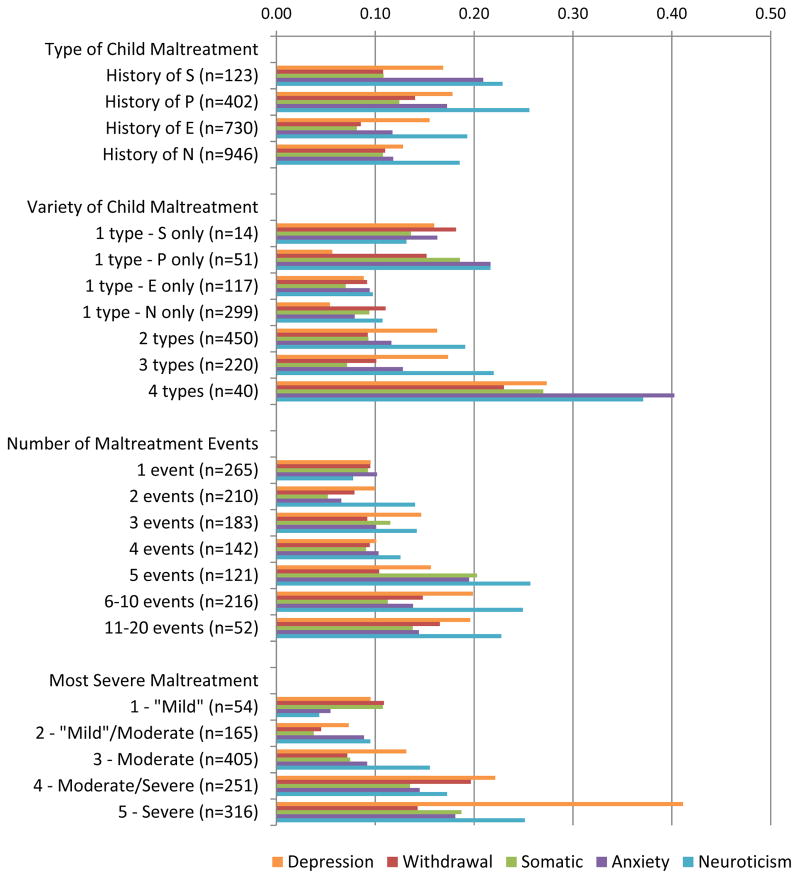

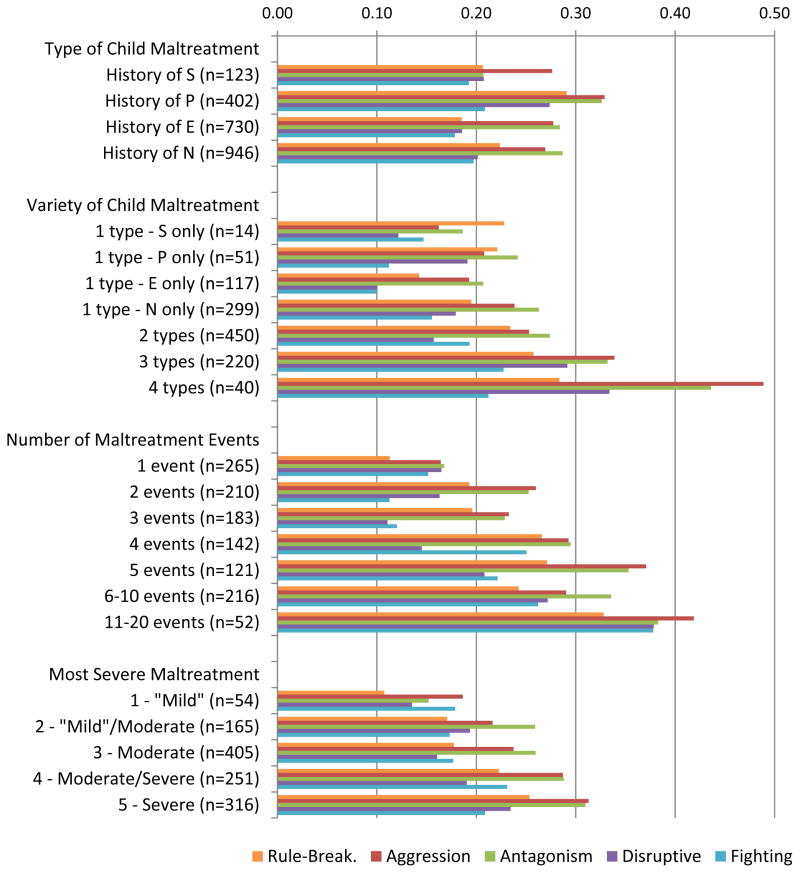

Figures 1 and 2 display differences between nonmaltreated children and specific subgroups of maltreated children. Because some psychiatric outcomes are skewed, differences between groups are represented using the nonparametric success rate difference (SRD) effect size; values of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.4 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively.32 Also displayed is the number of cases per CM category, as well as the effect sizes for CM type, variety, frequency, and severity across psychological outcomes. Figures 1 and 2 distinguish between measures of internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT), two broad factors that underlie personality and psychopathology20. Overall, these subgroup comparisons show that abused and neglected children experience all types of maladjustment at significantly higher rates than their non-maltreated counterparts, and that this maladjustment increases as CM grows more diverse, frequent, and severe.

Figure 1.

Internalizing effect sizes for type, variety, frequency, and severity of child maltreatment (CM). Each bar reflects an effect size (Success Rate Difference) from comparing different CM groups to the non-CM group.

Note. S = sexual abuse, P = physical abuse, E = emotional abuse, N = neglect. Effect sizes of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.4 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively. With the exception of the 1 type – S only (n = 14) bars, all displayed bars are significant at p<.01. Even the most “mild” form of CM was serious enough to reach the threshold for documentation.

Figure 2.

Externalizing effect sizes for type, variety, frequency, and severity of child maltreatment (CM). Each bar reflects an effect size (Success Rate Difference) from comparing different CM groups to the non-CM group.

Note. S = sexual abuse, P = physical abuse, E = emotional abuse, N = neglect. Effect sizes of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.4 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively. With the exception of the 1 type – S only (n = 14) bars, all displayed bars are significant at p<.01. Even the most “mild” form of CM was serious enough to reach the threshold for documentation.

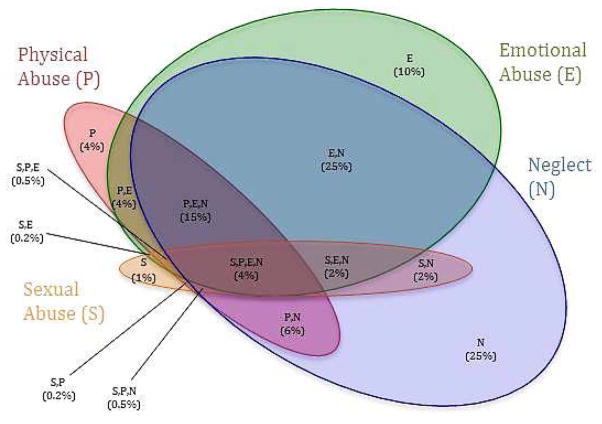

Co-Occurrence of CM

Figure 3 displays the rate of co-occurrence between the different types of CM. The size of the circles in Figure 3 is proportional to the number of children who experienced each type of CM, and the amount of overlap between circles is proportional to the co-occurrence of CM types. It is important to note that almost all sexual abuse cases (99%) occurred in the presence of another type of CM.

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence between different types of child maltreatment.

Note: The size of the circles is proportional to the number of children who experienced each type of maltreatment, and the amount of overlap between the circles is proportional to the co-occurrence of maltreatment types.

Multivariate Associations

Although subgroup comparisons support the assumption that CM is psychologically harmful, overlap among CM types and psychiatric outcomes is substantial. Thus, structural modeling is needed to disentangle these effects and directly test assumptions of non-equivalence, specificity, and non-universality.

Structural model

Structural equation modeling and measurement invariance models were fit using Mplus.33 In the structural model, independent variables were four types of previously documented CM, each with three indicators representing the number of documented CM events committed by three different perpetrators (mother, father, and other). Dependent variables were self-, peer-, and counselor-rated psychological factors, modeled as indicative of latent INT and EXT factors. Because the threshold for legal documentation of CM was high, maltreatment indicators were modeled as censored from below. For this type of analysis, the default Mplus estimator is maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR). Initially, the four types of CM were modeled separately. However, under this initial model there were extremely high correlations among physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect (average correlation = .82). Multicollinearity among these variables produced partial regression coefficients that were in the opposite direction of theory and of implausible magnitude (e.g., physical and emotional abuse were strongly predictive of positive outcomes); this is a typical consequence of multicollinearity34. Therefore, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect were modeled as indicators of a single “Non-Sexual CM” variable.

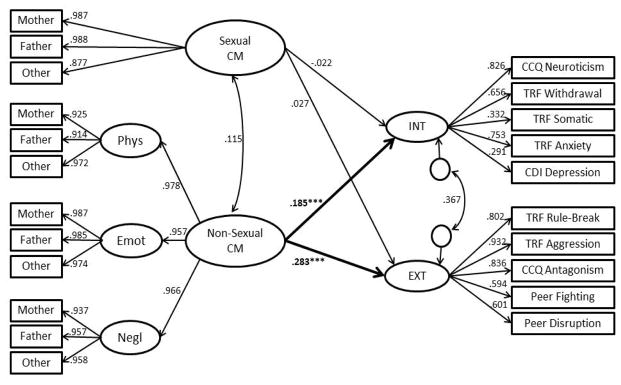

Displayed in Figure 4 is the final structural model, with prospectively assessed CM variables on the left side and psychological outcome variables on the right side. Arrows leading from the CM variables to the psychological variables represent regression paths, the predictive portion of the model. The child’s age and year of camp attendance were statistically controlled, though for the sake of clarity these two controls were omitted from the figure. Two INT factor loadings were of modest size, including the loadings for the TRF Somatic Complaints scale and the CDI Depression scale. However, the TRF Somatic Complaints scale has the lowest co-occurrence rates with the other TRF syndromes,35 and the correspondence between child self-reported depression and parent/teacher reports of child depression is typically low.36 Both scales were retained because somatic complaints are a common feature of adult internalizing disorders, and childhood depressive symptoms are not easily detected by an informant; the latent variable (INT) captures shared variance across sources, thus mitigating informant discrepancies.37

Figure 4.

Structural model predicting psychiatric outcomes from child sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect after controlling for age and year of camp attendance.

*** p < .001. CM = child maltreatment, Phys = physical abuse, Emot = emotional abuse, Negl = neglect, INT = internalizing, EXT = externalizing, CCQ = California Child Q-set, TRF = Teacher Report Form, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory, Peer = peer ratings.

The full structural model was used to examine each of the four assumptions regarding the effects of CM, including whether CM significantly predicts psychopathology (harmfulness), whether some types of CM more strongly predict psychopathology than others (non-equivalence), whether CM predicts specific types of psychopathology incremental to the underlying INT and EXT factors (specificity), and whether the full structural model varies across sex and race (non-generalizability).

Harmfulness assumption

In support of the harmfulness assumption, non-sexual forms of CM, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect, significantly predicted both INT (β =.22, p <.001) and EXT (β = .30, p <.001) after accounting for age and year of camp attendance. In line with previous meta-analytic evidence, sexual CM was not significantly related to INT or EXT.

Non-equivalence assumption

Contrary to the non-equivalence assumption, the structural model indicates equivalence between different forms of CM. With the exception of sexual CM, which was not predictive of psychiatric outcomes, non-sexual forms of CM load heavily on a single factor (factor loadings ranged from .96–.98).

Specificity assumption

Contrary to the specificity assumption, the structural model indicates non-specificity. Greater frequency of non-sexual CM predicts greater rates of INT and EXT, but beyond these effects, CM does not predict specific psychiatric outcomes. In each of 20 analyses, the structural model in Figure 2 was altered to add a direct pathway between CM and a specific psychiatric outcome (e.g., Anxiety). In all 20 cases (2 CM predictors, 10 psychiatric outcomes), the specific regression coefficient was very small in size (all βs < .02) and not significant.

Non-universality assumption

Contrary to the non-universality assumption, invariance analyses indicate generalizability of effects across groups in the structural model. For sex and race, Table 1 presents fit statistics for three models that 1. allow factor loadings, intercepts, and regressions to vary across groups; 2. set factor loadings and intercepts equal across groups to evaluate strong measurement invariance; and 3. set regressions equal across groups to evaluate structural invariance. For both sex and race, the improvement in fit (i.e., generally lower values for fit statistics) across models indicates both measurement and structural invariance.

Table 1.

Measurement and structural invariance across sex (female/male) and race (Black/White).

| Parameters | AIC | BIC | aBIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | ||||

| Model 1 - Configural Invariance: Intercepts free, factor loadings free, regression paths free | 160 | 172013 | 171902 | 171410 |

| Model 2 - Strong Measurement Invariance: Intercepts equal across groups, factor loadings equal across groups, regression paths free | 116 | 171090 | 171755 | 171386 |

| Model 3 - Structural Invariance: Intercepts equal across groups, factor loadings equal across groups, regression paths equal across groups | 112 | 171090 | 171732 | 171376 |

| Race (Black vs. White) | ||||

| Model 1 - Configural Invariance: Intercepts free, factor loadings free, regression paths free | 160 | 155781 | 156673 | 156171 |

| Model 2 - Strong Measurement Invariance: Intercepts equal across groups, factor loadings equal across groups, regression paths free | 116 | 155738 | 156393 | 156025 |

| Model 3 - Structural Invariance: Intercepts equal across groups, factor loadings equal across groups, regression paths equal across groups | 112 | 155741 | 156373 | 156017 |

Comment

Our results suggest that physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect are equivalent insults that affect broad psychiatric vulnerabilities. Our results also highlight an important problem—one that may explain mixed findings in the child sexual abuse literature. Specifically, child sexual abuse is an infrequent event that is almost always accompanied by other types of CM. This pattern of rarity and lopsided co-occurrence has several consequences. First, it poses a statistical constraint that severely attenuates the correlation between sexual and non-sexual CM. For example, if nearly all people with Disorder X are men, but very few men have Disorder X, then sex will be nearly uncorrelated with Disorder X (despite the fact that almost all cases are men). This constraint explains why sexual CM and non-sexual CM are weakly correlated factors in our structural model: Whereas 89% of sexual CM cases are accompanied by non-sexual CM, only 9% of non-sexual CM cases are accompanied by sexual CM.

Second, there is no practical way to understand the specific consequences of sexual CM because its correlates may be attributed to other forms of co-occurring CM. Statistically controlling for co-occurring CM partials out what little covariation is left after the attenuation caused by unidirectional redundancy, further gutting the variance in the sexual abuse variable and producing unreliable parameter estimates. Alternatively, samples of “pure” sexual abuse cases (without co-occurring CM) are extremely rare and unrepresentative. This intractable issue may explain why research on sexual CM produces mixed results. The infrequency of sexual CM, combined with its unidirectional redundancy with non-sexual CM, attenuates their correlation and undermines efforts to identify the effects of sexual abuse, which are almost certainly detrimental. As such, previous meta-analyses of the child sexual abuse literature7,8 may produce misleading results.

This study also partially addresses a potentially confounding variable: socioeconomic status (SES). Because factors associated with low SES predict the occurrence of both CM38 and mental illness39, low SES may explain the association between CM and psychopathology. In the current study, all children were sampled from low-SES families, attenuating this potential SES confound. However, it should be noted that a different pattern of results may be found in higher SES populations.

Sexual abuse may be an underreported type of CM that is difficult for child protection agencies to substantiate. Thus, an important limitation to overcome is getting to these missed cases; doing so may also help address the methodological problem of rarity and lopsided co-occurrence. Other limitations of this study include reliance on official documentation, absence of data regarding psychopathology prior to CM, and use of psychological reports from counselors and children who only knew the participants in the camp setting.

Conclusions

Complex etiological models of CM effects on mental health may be less illuminating than parsimonious models emphasizing pathways to broad vulnerability factors. Evidence suggests this may also be true of childhood adversity, more generally.40 Thus, treatments tailored to specific types of abuse, populations, or outcomes may be less effective than those aimed at mitigating early changes in the neurobiological and temperamental factors that dispose individuals towards psychopathology. Such treatments are likely to have broad and comprehensive benefits. Finally, population-level prevention and intervention strategies should not ignore the considerable psychological harms imposed by emotional abuse, which rival those of physical abuse and neglect. Taken together with high worldwide prevalence2 and evidence that emotional and physical pain share a common somatosensory representation in the brain41,42, it is clear that emotional abuse is widespread, painful, and destructive.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA036282; Vachon) and (DA12903, DA1774; Cicchetti and Rogosch), the National Institute of Mental Health (MH083979; Cicchetti and Rogosch), and the Spunk Fund, Inc. (Cicchetti). We would like to thank the children, families, counselors, and research staff at the Mt. Hope Family Center, Rochester NY, who participated in this work, and colleagues Jody Todd Manly and Sheree L. Toth.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None. The sponsors had no additional role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Vachon had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:478–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van Ijzendoorn MH. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2012;21(8):870–890. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS med. 2012;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browne A, Finkelhor DA. Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall-Tackett K, Williams L, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:164–180. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polusny M, Follette V. Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: theory and review of the empirical literature. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rind B, Tromovitch P. A meta-analytic review of findings from national samples on psychological correlates of child sexual abuse. J Sex Res. 1997;34:237–255. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rind B, Tromovitch P, Bauserman R. A meta-analytic examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse using college samples. Psychol Bull. 1998;124:22–53. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilienfeld SO. When worlds collide: Social science, politics, and the Rind et al. (1998) child sexual abuse meta-analysis. Am Psychol. 2002;57(3):176–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ondersma SJ, Chaffin M, Berliner L, Cordon I, Goodman GS. Sex with children is abuse: Comment on Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman (1998) Psychol Bull. 2001;127:701–714. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallam SJ, Gleaves DH, Cepeda-Benito A, Silberg JL, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. The effects of child sexual abuse: Comment on Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman (1998) Psychol Bull. 2001;127:715–733. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rind B, Tromovitch P, Bauserman R. The validity and appropriateness of methods, analyses, and conclusions in Rind et al. (1998): A rebuttal of victimological critique from Ondersma et al. (2001) and Dallam et al (2001) Psychol Bull. 2001;127:734–758. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tromovitch P, Rind B. Child sexual abuse definitions, meta-analytic findings, and a response to the methodological concerns raised by Hyde (2003) Int J Sexual Health. 2007;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiecher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown GW, Harris TO. Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. 5. London, England: Routledge; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott J, Varghese D, McGrath J. As the twig is bent, the tree inclines: Adult mental health consequences of childhood adversity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):111–112. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson TL, Miller WR. Concomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems: A review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:27–77. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AB, Cross T. Ethnicity in child maltreatment research: A replication of Behl et al.’s content analysis. Child Maltreat. 2006;11(1):16–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559505278272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Brown K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;37(3):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Arellano MA. The importance of culture in treating abused and neglected children: An empirical review. Child Maltreat. 2001;6(2):148–157. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(4):759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Add Health, The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. [Accessed 11/11/14];Program code for race. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/code/race.

- 24.Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 7–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, et al. Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4): Report to congress, executive summary. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration of Children and Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Manly JT. Maternal maltreatment classification interview. Rochester, NY: 2003. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cicchetti D, Manly JT. A personal perspective on conducting research with maltreating families: Problems and solutions. In: Brody G, Sigel I, editors. Methods of family research: Families at risk. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990. pp. 87–133. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory: A self-rated depression scale for school-aged youngsters. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh; 1982, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Block J, Block JH. The California Child Q-set. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatr. 2006;59(11):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41:673–690. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez R, Vance A. Confirmatory factor analysis, latent profile analysis, and factor mixture modeling of the syndromes of the child behavior checklist and teacher report form. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(4):1307–1316. doi: 10.1037/a0037431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moretti MM, Fine S, Haley G, Marriage K. Childhood and adolescent depression: Child-report versus parent-report information. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24(3):298–302. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slack KS, Holl J, McDaniel M, Yoo J, Bolger K. Understanding the risks of child neglect: An exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreat. 2004;9:395–408. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kross E, Berman MG, Mischel W, Smith EE, Wager TD. Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6270–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102693108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]