Abstract

Background

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) has emerged as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality since 2002 on tribal lands in Arizona. The explosive nature of this outbreak and the recognition of an unexpected tick vector, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, prompted an investigation to characterize RMSF in this unique setting and compare RMSF cases to similar illnesses.

Methods

We compared medical records of 205 patients with RMSF and 175 with non-RMSF illnesses that prompted RMSF testing during 2002–2011 from 2 Indian reservations in Arizona.

Results

RMSF cases in Arizona occurred year-round and peaked later (July–September) than RMSF cases reported from other US regions. Cases were younger (median age, 11 years) and reported fever and rash less frequently, compared to cases from other US regions. Fever was present in 81% of cases but not significantly different from that in patients with non-RMSF illnesses. Classic laboratory abnormalities such as low sodium and platelet counts had small and subtle differences between cases and patients with non-RMSF illnesses. Imaging studies reflected the variability and complexity of the illness but proved unhelpful in clarifying the early diagnosis.

Conclusions

RMSF epidemiology in this region appears different than RMSF elsewhere in the United States. No specific pattern of signs, symptoms, or laboratory findings occurred with enough frequency to consistently differentiate RMSF from other illnesses. Due to the nonspecific and variable nature of RMSF presentations, clinicians in this region should aggressively treat febrile illnesses and sepsis with doxycycline for suspected RMSF.

Keywords: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, American Indians, AIAN, tick-borne, Rhipicephalus sanguineus

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), caused by the tick-borne pathogen Rickettsia rickettsii, was sporadically reported in Arizona prior to confirmation of a fatal case on an American Indian reservation in 2003, linked to an unexpected vector, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (the brown dog tick) [1, 2]. Through 2011, 219 human RMSF cases and 16 fatalities (case fatality rate, 7.3%) were reported from 4 Arizona reservations, and 2 additional reservations reported RMSF exposure in humans and/or dogs during 2012 [3, 4]. Affected tribes reported R. sanguineus infestation and large populations of free-roaming dogs [1, 2]. During the last decade, RMSF outbreaks caused by R. sanguineus have been documented in Mexico and South America [5, 6]. However, R. sanguineus ticks and the R. rickettsii organism found in Arizona are genetically distinct from those in Mexico, and the origin of the Arizona outbreak and reasons for its recent emergence remain unclear [5, 7, 8].

RMSF is easily treated with tetracyclines early in the illness, but other broad-spectrum antibiotics are not effective and doxycycline is the treatment of choice in patients of all ages [9–11]. The nonspecific clinical presentation of RMSF, lack of a sensitive early diagnostic test, and necessity of choosing an antibiotic not typically used for other common illnesses or sepsis make identification and management of cases challenging. Physicians need key information to guide early clinical decisions. Geographic patterns of infection and epidemiologic risk factors are important variables in these decisions.

The Arizona RMSF outbreak is unusual because it occurred in association with a previously unrecognized tick vector in the United States, and emerged rapidly in a region where RMSF was not previously recognized. Its recent detection in tribal communities where multiple documented underlying health disparities exist [12, 13] lends importance and urgency to characterizing the epidemiology of this outbreak. The unique combination of host, vector, pathogen, and environmental variables within this outbreak suggest that important differences in the clinical manifestations and RMSF epidemiology may exist compared to the broader US experience [9, 14–17]. This study describes RMSF in this emerging setting to aid in differentiation of this potentially deadly disease from similar illnesses.

METHODS

Data, Definitions, and Analysis

We performed a retrospective medical record review of patients prompting R. rickettsii testing from 1 June 2002 through 30 September 2011 in community A, and 1 January 2005 through 30 September 2011 in community B at community Indian Health Service health facilities and 11 referral hospitals. At least 1 illness symptom prompted RMSF testing; individuals tested without symptoms following a tick bite or exposures were excluded. This broad definition was intended to capture a complete spectrum of illness in patients tested for RMSF, considering that RMSF illnesses may be atypical or nonspecific.

A confirmed RMSF case was defined as a person reporting illness and a 4-fold change in immunoglobulin G (IgG)– or immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody titer reactive with R. rickettsii antigen by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) between paired serum specimens taken after the onset of symptoms with at least 1 titer of ≥1:128 dilution, or detection of R. rickettsii DNA in a clinical specimen via amplification of a specific target by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, or demonstration of spotted fever group antigen in a biopsy or autopsy specimen by immunohistochemical staining.

A probable RMSF case was defined as a person reporting illness and who did not meet criteria for a confirmed case, and had serologic evidence of elevated IgG or IgM antibody reactive with R. rickettsii antigen by IFA with at least 1 titer of ≥1:128 dilution.

A non-RMSF illness was defined as a person reporting illness and had at least 2 negative serologic R. rickettsii antigen titers (<1:64) and the second titer drawn no earlier than day 14 after symptom onset.

All patients who met 1 of these definitions were included in this review. A subset of case samples underwent sequencing and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis targeting rickettsial DNA, to confirm R. rickettsii as the pathogen. The nucleic acid sequence of this outbreak strain was published previously [5, 7]. Patients with titers of 1:64 that did not increase were excluded from the review, because this low-level reactivity was considered insufficient evidence to confidently confirm or rule out recent infection.

Demographic information, medical history, illness history, and clinical information were anonymously recorded. Symptoms or exposures were excluded from analysis if there was no documentation of their presence or absence. Data were analyzed using EpiInfo [18]. Statistical differences in categorical variables were evaluated using a χ2 test, and when the expected value of a cell was <5, Fisher exact test was used. Statistical differences in continuous variables were evaluated using an analysis of variance test or the Mann–Whitney/Wilcoxon 2-sample test when a nonparametric test was more appropriate. Statistical significance was set at α = .05.

Health Facilities and Service Populations

Community A and B health facilities are, respectively, rural 40-bed and 8-bed Indian Health Service hospital and outpatient facilities on tribal reservations in Arizona, with user populations of >16 100 and >11 900 persons. Neither facility has an intensive care unit, resulting in patient transfers for specialized care to referral facilities.

Definitions of Terms

A case is a confirmed or probable RMSF case; dog contact is any documentation of dog interaction, including dog ownership or feeding strays; fever is a temperature ≥38°C (100.4°F) or reported fever by the patient or caretaker. Tick exposure includes tick bites and ticks observed on pets or in frequented environments. Abnormal laboratory values are those outside standard range; liver tests were based on age-adjusted standards.

Ethics Review

The project was intended to prevent disease in response to an immediate public health threat and was therefore judged exempt by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s institutional review board on a nonresearch basis. The study was approved by the community A and B tribal councils through resolutions 11-2010-302 and AU-11-223, respectively.

RESULTS

Demographics

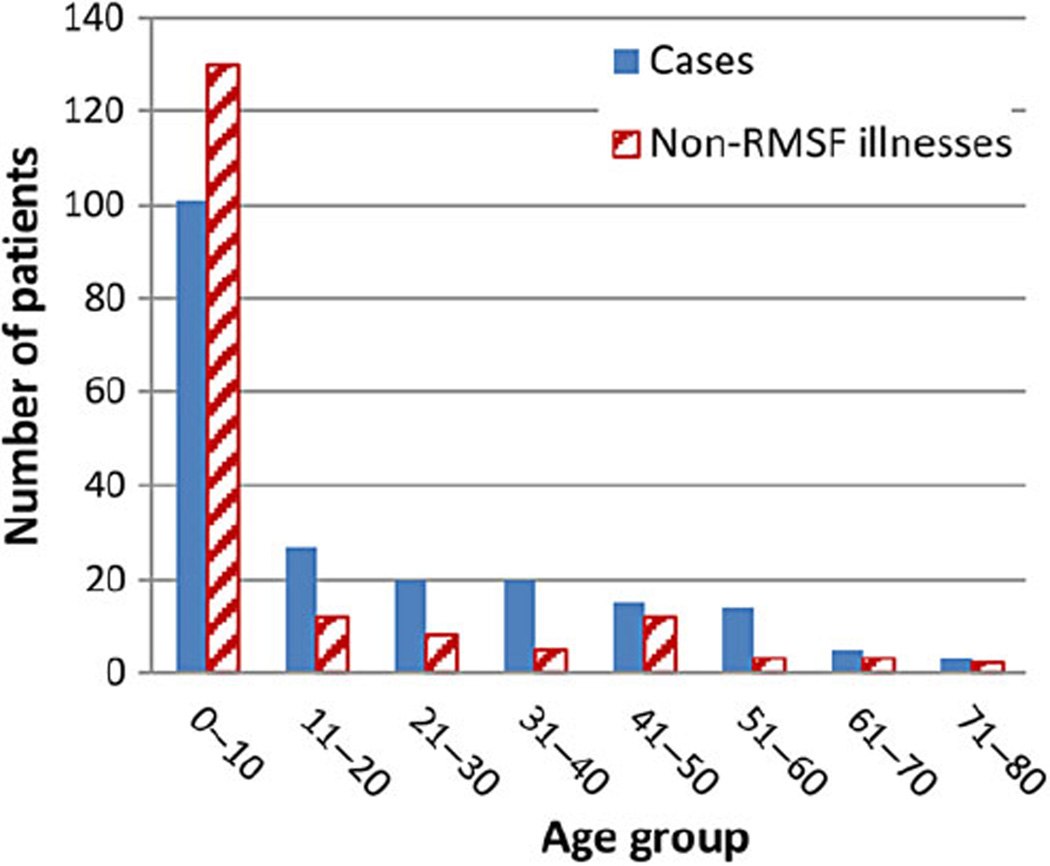

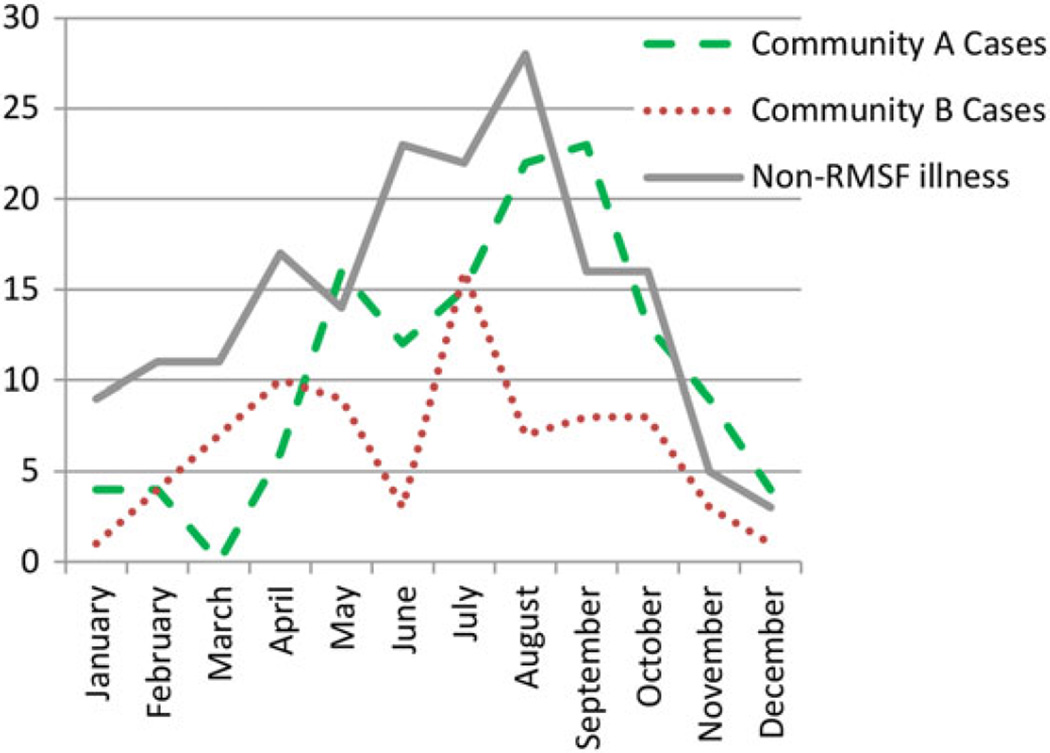

We identified 205 patients with RMSF (cases) and 175 with non-RMSF illnesses (Table 1). Among all subjects, 52% were male and all were American Indians except 1 person who worked on tribal lands. The median age among cases was 11 years, significantly higher than that of patients with non-RMSF illnesses (median, 2 years; Figure 1). Among cases, 85 had confirmed RMSF and 120 had probable RMSF. Cases occurred in each month, with seasonal differences in different peak months in communities A and B (September and July, respectively; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Demographics, Exposures, and Past Medical History Among Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) Cases and Patients With Non-RMSF Illness From 2 Tribal Communities in Arizona

| Demographic | Cases, No. (%) | Non-RMSF Illness, No. (%) | Risk Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 205 | 175 | ||

| Age, y, median/mean (range)* | 11/19.8 (7 mo–78 y) | 2/11.0 (2 mo–79 y) | P = .000 | |

| Race | 204 American Indian, 1 white | 175 American Indian | NA | NA |

| Male sex | 106/205 (52) | 92/174 (53) | 0.97 | .80–1.18 |

| Exposures | ||||

| Dog contact* | 77/90 (86) | 60/87 (69) | 1.73 | 1.08–2.77 |

| Tick exposure* | 73/132 (55) | 48/118 (41) | 1.32 | 1.04–1.67 |

| Sick contacts* | 17/43 (40) | 8/39 (21) | 1.50 | 1.01–2.20 |

| Travel* | 6/37 (16) | 1/35 (3) | 1.80 | 1.21–2.67 |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Alcoholism (age >17 y) | 22/81 (27) | 8/35 (23) | 1.07 | .83–1.38 |

| Asthma* | 17/205 (8) | 2/174 (1) | 1.71 | 1.43–2.06 |

| Autoimmune disorder | 2/205 (1) | 3/174 (2) | 0.74 | .25–2.16 |

| Diabetes (age >17 y) | 18/82 (22) | 7/35 (20) | 1.04 | .78–1.37 |

| Heart disease | 4/205 (13) | 3/174 (2) | 1.05 | .55–2.02 |

| Hepatitis | 3/204 (2) | 3/173 (2) | 0.92 | .41–2.10 |

| Hypertension | 26/205 (13) | 13/174 (8) | 1.27 | .99–1.62 |

| Lung disease, chronic | 4/205 (2) | 5/174 (3) | 0.82 | .39–1.71 |

| Renal insufficiency/failure | 0/204 (0) | 3/174 (2) | 0 | 0–1.65 |

| Thyroid disease | 6/205 (3) | 4/174 (2) | 1.11 | .66–1.86 |

| Tuberculosis | 2/204 (1) | 2/174 (1) | 0.93 | .35–2.48 |

The following conditions were not present in any subjects included in this study: AIDS/human immunodeficiency virus, transplant recipients, asplenia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

The following conditions were present in 1 case and 1 patient with non-RMSF illness: cancer, cerebrovascular accident/stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and sickle cell disease.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; RMSF, Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Statistically significant difference.

Figure 1.

Number of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) cases and non-RMSF illnesses by age group in 2 tribal communities in Arizona.

Figure 2.

Month of symptom onset of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) cases and non-RMSF illnesses in 2 tribal communities in Arizona.

Exposures and Historical Medical Conditions

Dog contact and tick exposure were significantly more frequent among cases than among patients with non-RMSF illnesses (86% vs 69% and 55% vs 41%, respectively; Table 1). Sick contacts and travel frequency differed significantly between cases and patients with non-RMSF illnesses, but tick exposure was infrequently reported in both. The only medical history significantly more frequent among RMSF cases than patients with non-RMSF illnesses was asthma, occurring in 8% of cases. Alcoholism and diabetes among adults were the most common underlying health conditions among cases; the frequency did not differ significantly from non-RMSF illnesses (27% vs 23% and 22% vs 20%, respectively).

Medical Care and Treatment

Cases and patients with non-RMSF illnesses both presented to health facilities a median of 2 times during illness (cases: range, 0–9 and mean = 1.87; non-RMSF illness: range, 0–7 and mean = 1.94). Both first presented for care on median day 2 (cases: range, 1–11; non-RMSF illness: range, 1–12). Cases were significantly more likely to be treated with doxycycline than were patients with non-RMSF illnesses (87% vs 78%, respectively; risk ratio [RR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–2.62), and children more often than adults (91% vs 81%, respectively; RR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.05–4.37).

Fifteen fatalities (7.3%) and 86 (42.0%) hospitalizations (including 29 ICU admissions [14.1%]) occurred among cases. There were no deaths and 29 (16.6%) hospitalizations (7 ICU admissions [4.0%]) among patients with non-RMSF illnesses. Cases were significantly more likely to result in fatality (RR undefined; P = .0007), hospitalization (RR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.75–3.66; P < .0001), and ICU admission (RR, 3.53; 95% CI, 1.59–7.87; P < .0001) compared with patients with non-RMSF illnesses.

Signs and Symptoms

Fever was frequent but not universal among cases (81%; Table 2). Temperature maximum and range did not differ significantly between cases and patients with non-RMSF illnesses (38.8°C [range, 35.8°C–41.3°C] vs 38.4°C [range, 35.4°C–41.3°C]; Table 2). Although fever was present in all fatalities [11], no fever was documented in 8 of 85 (9%) confirmed cases (3 of whom were hospitalized) and 30 of 117 (26%) probable cases (4 of whom were hospitalized). Twenty cases without documented fever had a rash, and 14 reported a tick bite and other symptoms. One afebrile patient presented 5 days after symptom onset, required intensive care, suffered digit necrosis, and had a maximum temperature of 37.7°C. Patients without documented fever averaged 1.4 outpatient visits (range, 1–4). Rash occurred in 130 of 192 (68%) cases and 92 of 166 (55%) non-RMSF illnesses. Twenty of 119 cases with rash descriptions reported pruritic rash (17%); another 4% were vesicular and 2% were urticarial, descriptions not usually associated with RMSF.

Table 2.

Symptoms Among Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) Cases and Non-RMSF Illnesses From 2 Tribal Communities in Arizona

| Symptom | Cases, No. (%) | Non-RMSF Illness, No. (%) | Risk Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General and skin | ||||

| Fever | 164/202 (81) | 142/169 (84) | 0.92 | .73–1.15 |

| Tmax, median (range) | 38.2°C (35.8–41.3) | 38.3°C (35.4–41.3) | P = .896 | |

| Rash* | 130/192 (68) | 92/166 (55) | 1.28 | 1.04–1.59 |

| Fever and rash* | 108/190 (57) | 71/164 (43) | 1.29 | 1.06–1.57 |

| Fever and tick exposure | 58/131 (44) | 40/117 (34) | 1.22 | .96–1.53 |

| Rash and tick exposure* | 48/128 (38) | 23/114 (20) | 1.44 | 1.15–1.81 |

| Triad (fever/rash/tick exposure)* | 41/127 (32) | 18/113 (16) | 1.46 | 1.16–1.84 |

| Headache | 78/135 (58) | 37/77 (48) | 1.15 | .94–1.42 |

| Fatigue | 60/130 (46) | 23/65 (35) | 1.16 | .95–1.41 |

| Myalgia | 53/129 (41) | 28/61 (46) | 0.94 | .77–1.15 |

| Chills | 47/133 (35) | 24/69 (35) | 1.01 | .82–1.24 |

| Lethargy | 24/121 (20) | 12/57 (21) | 0.98 | .75–1.26 |

| Irritability | 20/123 (16) | 38/87 (44)* | 0.51 | .35–.74 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 5/129 (4) | 7/92 (8) | 0.70 | .36–1.38 |

| Head/eyes/ears/nose/throat | ||||

| Nasal congestion* | 43/155 (28) | 66/136 (49) | 0.64 | .49–.83 |

| Sore throat | 27/134 (20) | 12/76 (16) | 1.11 | .87–1.41 |

| Red or draining eyes* | 22/148 (15) | 9/111 (8) | 1.28 | 1.01–1.65 |

| Ear pain | 13/126 (10) | 15/69 (22) | 0.69 | .45–1.04 |

| Periorbital edema | 7/147 (5) | 3/105 (3) | 1.21 | .80–1.84 |

| Pulmonary/cardiovascular | ||||

| Cough* | 68/169 (40) | 73/138 (53) | 0.79 | .64–.98 |

| Peripheral edema* | 18/147 (12) | 3/120 (3) | 1.63 | 1.32–2.02 |

| Chest pain | 12/129 (9) | 4/65 (6) | 1.17 | .86–1.58 |

| Wheezing | 9/164 (6) | 14/147 (10) | 0.73 | .43–1.22 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Nausea* | 74/156 (47) | 38/109 (35) | 1.23 | 1.01–1.50 |

| Emesis | 77/169 (46) | 58/144 (40) | 1.10 | .90–1.35 |

| Anorexia | 51/125 (41) | 51/106 (48) | 0.87 | .68–1.11 |

| Diarrhea | 52/163 (32) | 45/137 (33) | 0.98 | .78–1.23 |

| Abdominal pain | 48/154 (31) | 25/115 (22) | 1.22 | .99–1.50 |

| Hepatomegaly* | 7/145 (5) | 1/124 (1) | 1.65 | 1.24–2.20 |

| Jaundice | 6/149 (4) | 3/113 (3) | 1.18 | .73–1.90 |

| Dysphagia | 3/120 (3) | 1/51 (2) | 1.07 | .60–1.90 |

| Splenomegaly | 2/143 (1) | 4/125 (3) | 0.62 | .20–1.93 |

| Neurologic | ||||

| Dizziness | 21/110 (19) | 5/48 (10) | 1.20 | .96–1.50 |

| Mental status change* | 29/169 (17) | 5/137 (4) | 1.66 | 1.38–1.99 |

| Neck pain* | 16/141 (11) | 2/74 (3) | 1.40 | 1.15–1.70 |

| Seizure | 7/142 (5) | 3/78 (4) | 1.09 | .72–1.65 |

| Photophobia | 5/117 (4) | 1/45 (2) | 1.16 | .80–1.68 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RMSF, Rocky Mountain spotted fever; Tmax, maximum documented temperature.

Statistically significant difference.

The triad of fever, rash, and tick exposure was significantly more frequent among cases than patients with non-RMSF illnesses (32% vs 16%, respectively; RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.16–1.84), but represented a minority of cases.

Headache occurred in a majority of cases, but was not statistically more frequent than among patients with non-RMSF illnesses (58% vs 48%). Nausea (47%), red or draining eyes (15%), mental status change (17%), peripheral edema (12%), hepatomegaly (5%), and neck pain (11%) were all significantly more frequent among cases than patients with non-RMSF illnesses, but occurred in a minority of patients.

Initial Laboratory Findings

The initial mean serum sodium level was significantly lower among cases than among patients with non-RMSF illnesses (Table 3), but only by 2 mEq/L (136 vs 138, respectively); chloride and potassium were similar (101 vs 103 and 3.9 vs 4.2, respectively). Initial platelet count mean was significantly lower among cases than among patients with non-RMSF illnesses, although not abnormally low for either group (269 × 103 platelets/µL vs 350 × 103 platelets/µL, respectively). However, initial platelet counts were low (<130 × 103 platelets/µL) in 17 of 141 (12%) cases, compared to only 2 of 144 (1.4%) among patients with non-RMSF illnesses. White blood cell counts were similar, but neutrophil count was significantly higher (67% vs 56%) and lymphocyte and monocyte counts significantly lower (20% vs 32% and 7% vs 8%, respectively) among cases vs patients with non-RMSF illnesses.

Table 3.

Initial Laboratory Findings for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) Cases and Non-RMSF Illnesses From 2 Tribal Communities in Arizona

| Laboratory Test | Mean Laboratory Values for Casesa |

No. | Mean Laboratory Values for Patients With Non-RMSF Illnessa |

No. | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count, ×103 cells/µL | 11H | 183 | 11H | 144 | .587 |

| WBC differential | |||||

| Neutrophils, %* | 67 | 181 | 56 | 143 | .000 |

| Bands, % | 10 | 83 | 6 | 43 | .975 |

| Lymphocytes, %** | 20L | 179 | 32 | 139 | .000 |

| Monocytes, %** | 7 | 179 | 8 | 140 | .003 |

| Eosinophils, % | 1.2 | 179 | 1.4 | 139 | .45 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL* | 13.9 | 140 | 12.8 | 134 | .000 |

| Hematocrit, %* | 40.4 | 141 | 38.4 | 134 | .002 |

| Platelet count, ×103 platelets/µL** | 269 | 141 | 350 | 144 | .000 |

| Sodium, mEq/L** | 136L | 173 | 138 | 135 | .043 |

| Potassium, mEq/L** | 3.9 | 134 | 4.2 | 126 | .001 |

| Chloride, mEq/L** | 101 | 128 | 103 | 125 | .030 |

| Bicarbonate, mEq/L | 22 | 135 | 22 | 125 | .371 |

| Creatinine, mEq/L | 1.0 | 134 | 0.7 | 126 | .084 |

| BUN, mEq/L | 14 | 134 | 11 | 125 | .174 |

| Glucose, mEq/L | 114H | 147 | 108H | 120 | .786 |

| Adult SGPT/ALT, IU/L* | 57.1H | 70 | 29.7 | 27 | .017 |

| Child SGPT/ALT, IU/L | 38.5H | 92 | 27.1 | 90 | .590 |

| Adult SGOT/AST, IU/L* | 140.1H | 70 | 58.0H | 27 | .052 |

| Child SGOT/AST, IU/L | 91.0H | 93 | 56.4H | 91 | .441 |

| Adult ALP, IU/L | 130.2H | 69 | 132.2H | 26 | .862 |

| Child ALP, IU/L | 223.9 | 92 | 225.6 | 90 | .876 |

| Adult GGT | 147.1H | 13 | 223.0H | 11 | .415 |

| Child GGT | 35.8H | 16 | 25.7 | 24 | .478 |

| Adult total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.1 | 57 | 0.7 | 27 | .083 |

| Child total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.8 | 86 | 0.5 | 82 | .068 |

| LDH, IU/L | 849H | 5 | 401H | 4 | .364 |

| C-reactive protein, IU/L | 50.0H | 11 | 50.0H | 16 | .983 |

| Albumin, g/dL** | 3.9 | 117 | 4.7 | 98 | .010 |

| PT, sec** | 15.8H | 27 | 42.3H | 15 | .022 |

| PTT, sec | 41.8H | 28 | 37.3H | 24 | .869 |

| INR** | 1.4 | 32 | 5.2H | 25 | .001 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 199H | 9 | 102H | 1 | .602 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL* | 1701H | 8 | 98.3 | 5 | .019 |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; INR, international normalized ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RMSF, Rocky Mountain spotted fever; SGOT/AST, serum glutamic oxalacetic transaminase/aspartate aminotransferase; SGPT/ALT, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase/alanine aminotransferase; WBC, white blood cell.

The superscript H indicates above normal limits; superscript L indicates below normal limits.

Significantly higher in cases than in patients with non-RMSF illness.

Significantly lower in cases than in patients with non-RMSF illness.

Initial liver test means were often elevated among both adults and children, but only alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase among adult cases were significantly higher among cases than among patients with non-RMSF illnesses. Among children, no liver tests were significantly more elevated among cases than among patients with non-RMSF illnesses. Tests evaluating inflammatory and coagulation status (C-reactive protein, D-dimer, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, international normalized ratio [INR], fibrinogen levels) were infrequently performed and usually conducted late in the illness course. When performed, prothrombin time, INR, and D-dimer differed significantly between cases and patients with non-RMSF illnesses.

Imaging Studies

Eighty-five (41.5%) confirmed or probable cases underwent at least 1 chest radiograph. Of these, 50 (59%) were interpreted as abnormal, and 19 (22%) specifically suggested pneumonia as a diagnosis. Head computed tomography (CT) scans were performed in 28 (13.6%) patients, and 9 chest (4.4%), 11 abdominal (5.4%), and 4 pelvic CTs (2.0%) were documented. Magnetic resonance imaging studies were performed in 6 cases (5 head and 1 extremity image). Ultrasound studies were performed in 21 (10.2%) cases including 17 abdominal, 4 chest or cardiac, and 2 extremity studies. Nine of 17 (52.9%) abdominal ultrasounds were abnormal, including abnormal gallbladders, pericholecystic fluid, gallstone pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, hepatosplenomegaly, and hepatic steatosis.

Non-RMSF Illnesses

Non-RMSF illnesses were not always ascribed to a specific pathogen, as is true for many nonspecific febrile illnesses that are diagnosed and treated routinely in primary care settings. In this cohort, illness cause was occasionally confirmed as another bacteria or virus through diagnostic testing (bacterial cultures, rapid viral tests).

DISCUSSION

This review characterizes RMSF clinical characteristics and epidemiology since its 2002 emergence in Arizona American Indian communities. In this series, RMSF disease patterns differed from US aggregate reports [19]. Although RMSF in most US regions peaks in June and July, consistent with seasonal activity of Dermacentor variabilis and Dermacentor andersoni ticks, in Arizona human cases peaked in July and September in community B and community A, respectively (Figure 2). Both communities exhibited a bimodal pattern of disease onset, with declines during June, the driest month in both communities. Aggregate cases peaked during July–October (54.6%), corresponding with seasonal monsoons and indicating that climatic factors such as moisture may contribute to the ecology of tick populations and RMSF transmission in this region. Seasonal analysis also indicates that human RMSF infection exists year-round.

Although fever was frequent among both cases and patients with non-RMSF illnesses (81% and 84%, respectively), it was not universally detected in all RMSF cases, and fever among cases was less frequent than reported in other studies, ranging from 94% to 100% [20–26]. While this finding contrasts with much of the reported literature, it should be noted that presence of fever is a required symptom for national RMSF reporting [27], likely resulting in an inclusion bias for fever frequency among US reported cases and also likely causing physicians to discount RMSF consideration for patients without fever. Thirty-eight cases (19%) in our series lacked documented fever during the course of illness, including 8 of 85 (9.4%) confirmed cases and 30 of 117 (25.6%) probable cases, suggesting that non-febrile RMSF illness occurs in this patient population, or that fever may not always be detected at the time a patient presents for care. For example, patients with sepsis or multiorgan system failure may exhibit hypothermia rather than fever, as occurred in late-presenting patients in this review. Probable cases only require 1 titer ≥1:128, allowing that an elevated titer may represent prior undetected RMSF illness with persistently elevated titer. However, a serosurvey conducted among children in the same communities during 2003–2004 revealed that only 10 of 215 (4.7%) children had R. rickettsii titers ≥1:128 [8]. The non-febrile probable cases, therefore, represent an RMSF infection that was either atypical because no fever was present or reported during patient evaluation, or a prior RMSF illness that was likely atypical or mild as it did not get tested for RMSF or come to medical attention at that time. Therefore, lack of fever should not exclude suspicion of RMSF in highly endemic areas such as this.

Strikingly, almost 50% of the cases in this review occurred in patients aged ≤10 years. The mean and median age among these cases (19.8 and 11 years, respectively) is lower than those of RMSF among the general US population (46 and 42 years, respectively) [28] and is lower than the mean age of 33 years reported among American Indians nationwide [29]. The younger age observed among these cases may reflect the unique vector and environmental factors in this region. The dog plays a central role in the RMSF transmission cycle in Arizona by harboring infected ticks [3, 8, 30]. Children may interact with dogs and their habitats more frequently than adults, resulting in greater exposure. In this series, the median age of those with non-RMSF illnesses was significantly lower than that of cases (2 vs 11 years, respectively), likely because fever was considered an important indicator for RMSF testing, and fever occurs commonly in young children.

The variability of symptom frequency in this population makes a presumptive diagnosis of RMSF difficult for the clinician. Fever, present in 81% of patients and 100% of fatalities, was the most reliable indicator to guide timely, effective, and optimal treatment, although fever was a late symptom in some fatalities [11]. No other signs or symptoms, either alone or in combination, were frequent enough to consistently identify at least two-thirds of RMSF cases. Rash was significantly more frequent among cases than among patients non-RMSF illnesses (68% vs 55%) but less common than that reported in numerous other studies [19–22, 24–26]. Although rash is often considered a hallmark of RMSF, 60% of RMSF cases in this review lacked a demonstrable rash initially and 32% failed to develop any rash while ill. Fever and rash together occurred in significantly more cases (57%) than in patients with non-RMSF illnesses (41%), but this combination is too infrequent to exclude RMSF from consideration if both are not present. Cough, nasal congestion, ear pain, and irritability occurred significantly more frequently among patients with non-RMSF illnesses than cases, but could not be used reliably to rule out RMSF as they also often occurred in cases. This series also demonstrates that presence or absence of abnormal laboratory values is not reliable for early treatment decisions, since in many cases values were only slightly abnormal or did not turn abnormal until disease was advanced.

In this study, imaging procedures reflect widespread vasculitis and organ involvement that accompanies most RMSF cases. Abnormal findings indicating nonspecific inflammation may unfortunately lead the clinician away from an underlying diagnosis of RMSF. Because 22% of chest radiographs in this series suggested pneumonia and 59% were abnormal, RMSF should be viewed as a potential etiology of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in this region. National guidelines for CAP treatment include doxycycline alone or paired with a β-lactam antibiotic [31], and clinicians should consider using doxycycline as part of standard treatment for CAP in patients from Arizona Indian reservations.

This review is subject to several limitations. Patients with titers <1:128 or with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing alone are included in the national case definition for reporting, but were excluded from this analysis to minimize false positives due to cross-reactivity from non-rickettsial antigens. Because RMSF serology cross-reacts with other species of Rickettsia (including Rickettsia massiliae, which was detected in at least 1 tick from the region and has been reported to cause human illness in international settings [32, 33]), patients diagnosed by serology alone could in theory be infected with other spotted fever group rickettsiae; however, R. massiliae patients typically have eschars [33, 34], which were lacking among these patients. Furthermore, PCR and nucleic acid testing of human specimens demonstrate R. rickettsii as the only detectable circulating Rickettsia species causing patient illness in this region.

In conclusion, this review characterizes RMSF during the first decade of emergence on tribal lands in Arizona. We found significant differences in the clinical presentation and epidemiology of disease compared to other parts of the United States, highlighting the need for region-specific medical education in this area. Providers in this region must remain vigilant for RMSF year-round and among younger ages than previously reported. The central role the dog plays in human exposure to rickettsial-containing R. sanguineus ticks emphasizes the importance of community-wide animal control and pet health programs, including tick prevention. The lack of a timely diagnostic RMSF test and the high fatality rate that occurs when RMSF treatment is delayed advocates that doxycycline be used aggressively among patients in this region presenting with a febrile illness and/or sepsis. Additional analysis investigating the high fatality rate in this population is published elsewhere [11].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank tribal health officials who wish to remain anonymous, as well as the Indian Health Service and private healthcare providers who care for this patient population every day. The study was approved by Community A and B tribal councils through resolutions 11-2010-302 and AU-11-223 respectively.

Footnotes

Author contributions. J. J. R. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Indian Health Service or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Reference to specific commercial products, manufacturers, companies, or trademarks do not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the US government, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Indian Health Service, or the CDC.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No potential conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Demma LJ, Traeger MS, Nicholson WL, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever from an unexpected tick vector in Arizona. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:587–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demma LJ, Eremeeva M, Nicholson WL, et al. An outbreak of Rocky Mountain spotted fever associated with a novel tick vector, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, in Arizona, 2004: preliminary report. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:342–343. doi: 10.1196/annals.1374.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maricopa County Department of Public Health. [Accessed 24 February 2015];Rocky Mountain spotted fever fact sheet. Available at: http://www.maricopa.gov/publichealth/Services/EPI/Diseases/rmsf/pdf/FactSheet.pdf.

- 4.Arizona Department of Health. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. [Accessed 24 February 2015];Arizona statistics. Available at: http://www.azdhs.gov/phs/oids/vector/rmsf/stats.htm.

- 5.Eremeeva ME, Zambrano ML, Anaya L, et al. Rickettsia rickettsii in Rhipicephalus ticks, Mexicali, Mexico. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:418–421. doi: 10.1603/me10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacheco RC, Moraes-Filho J, Guedes E, et al. Rickettsial infections of dogs, horses and ticks in Juiz de Fora, southeastern Brazil, and isolation of Rickettsia rickettsii from Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks. Med Vet Entomol. 2011;25:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2010.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eremeeva ME, Bosserman E, Zambrano M, Demma L, Dasch GA. Molecular typing of novel Rickettsia rickettsii isolates from Arizona. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:573–577. doi: 10.1196/annals.1374.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demma LJ, Traeger M, Blau D, et al. Serologic evidence for exposure to Rickettsia rickettsii in eastern Arizona and recent emergence of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in this region. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2006;6:423–429. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holman RC, Paddock CD, Curns AT, Krebs JW, McQuiston JH, Childs JE. Analysis of risk factors for fatal Rocky Mountain spotted fever: evidence for superiority of tetracyclines for therapy. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1437–1444. doi: 10.1086/324372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman AS, Bakken JS, Folk SM, et al. Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis—United States: a practical guide for physicians and other health-care and public health professionals. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-4):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan JJ, Traeger M, Humpherys D. Risk factors for fatal outcome from Rocky Mountain spotted fever in a highly endemic area—Arizona, 2002–2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1659–1666. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2010 final review. [Accessed 24 February 2015];2012 Dec; O-19. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2010/hp2010_final_review.pdf.

- 13.Keppel K, Garcia T, Hallquist S, Ryskuklova A, Agress L. Comparing racial and ethnic populations based on Healthy People 2010 objectives. Healthy People Stat Notes. 2008;26:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DuPont HL, Hornick RB, Dawkins AT, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever: a comparative study of the active immunity induced by inactivated and viable pathogenic Rickettsia rickettsii. J Infect Dis. 1973;128:340–344. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes SF, Burgdorfer W. Reactivation of Rickettsia rickettsii in Dermacentor andersoni ticks: an ultrastructural analysis. Infect Immun. 1982;37:779–785. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.779-785.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilford JH, Price WH. Virulent-avirulent conversions of Rickettsia rickettsii in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1955;41:870–873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.41.11.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Childs JE, Paddock CD. Passive surveillance as an instrument to identify risk factors for fatal Rocky Mountain spotted fever: is there more to learn? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:450–457. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dean AG, Dean JA, Coulombier D, et al. Epi Info, Version 3.5.3: a word processing, database, and statistic program for epidemiology on microcomputers. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalton MJ, Clarke MJ, Holman RC, et al. National surveillance for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, 1981–1992: epidemiologic summary and evaluation of risk factors for fatal outcome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:405–413. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmick CG, Bernard KW, D’Angelo LJ. Rocky Mountain spotted fever: clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological features of 262 cases. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:480–488. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, Schutze GE, et al. Clinical and laboratory features, hospital course, and outcome of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children. J Pediatr. 2007;150:180–184. 184.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayden AM, Marshall GS. Rocky Mountain spotted fever at Koair Children’s Hospital, 1990–2002. J Ky Med Assoc. 2004;102:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkland KB, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. Therapeutic delay and mortality in cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1118–1121. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirk JL, Fine DP, Sexton DJ, Muchmore HG. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. A clinical review based on 48 confirmed cases, 1943–1986. Medicine. 1990;69:35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilfert CM, MacCormack JN, Kleeman K, et al. Epidemiology of Rocky Mountain spotted fever as determined by active surveillance. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:469–479. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linnemann CC, Jr, Janson PJ. The clinical presentations of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Comments on recognition and management based on a study of 63 patients. Clin Pediatr. 1978;17:673–679. doi: 10.1177/000992287801700901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) (Rickettsia rickettsii) [Accessed 24 February 2015];2008 case definition. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/NNDSS/script/casedef.aspx?CondYrID=828&DatePub=1/1/2008.

- 28.Openshaw JJ, Swerdlow DL, Krebs JW, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 2000–2007: interpreting contemporary increases in incidence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:174–182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holman RC, McQuiston JH, Haberling DL, Cheek JE. Increasing incidence of Rocky Mountain spotted fever among the American Indian population in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:601–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dantas-Torres F. The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latreille, 1806) (Acari: Ixodidae): from taxonomy to control. Vet Parasitol. 2008;152:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eremeeva ME, Bosserman EA, Demma LJ, et al. Isolation and identification of Rickettsia massiliae from Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks collected in Arizona. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5569–5577. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00122-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Garcia JC, Portillo A, Nunez MJ, et al. A patient from Argentina infected with Rickettsia massiliae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:691–692. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitale G, Mansueto S, Rolain J-M, Raoult D. Rickettsia massiliae human isolation [letter] [Accessed 24 February 2015];Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050850. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1201.050850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]