In middle-aged persons without knee osteoarthritis but with risk factors for it, linear intrameniscal signal intensity on MR images of the medial meniscus was highly unlikely to resolve and should be considered a risk factor for a degenerative medial meniscal tear.

Abstract

Purpose

To assess the natural history of intrameniscal signal intensity on magnetic resonance (MR) images of the medial compartment.

Materials and Methods

Both knees of 269 participants (55% women, aged 45–55 years) in the Osteoarthritis Initiative without radiographic knee osteoarthritis (OA) and without medial meniscal tear at baseline were studied. One radiologist assessed 3-T MR images from baseline and 24-, 48-, and 72-month follow-up for intrameniscal signal intensity and tears. A complementary log-log model with random effect was used to evaluate the risk of medial meniscal tear, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and knee side.

Results

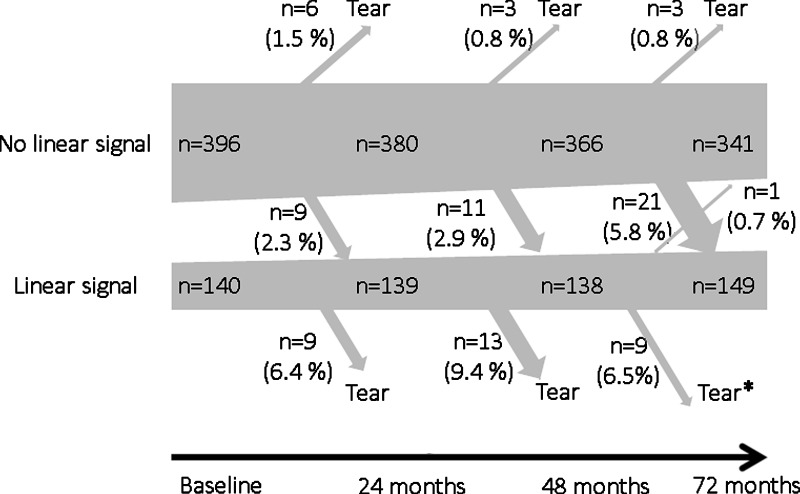

At baseline, linear intrameniscal signal intensity in the medial compartment was present in 140 knees (26%). Once present, regression only in a single knee was observed. In 31 knees (19%) with linear intrameniscal signal intensity at any of the first three time points, the signal intensity progressed to a tear in the same segment, and in a single knee, the tear occurred in an adjacent segment. The corresponding number of tears without prior finding of intrameniscal signal intensities was 11 (3%). In the adjusted model, the hazard ratio for developing medial meniscal tear was 18.2 (95% confidence interval: 8.3, 39.8) if linear intrameniscal signal intensity was present, compared when there was no linear signal intensity. There was only one of 43 knees with injury reported in conjunction with the incident tear.

Conclusion

In middle-aged persons without OA, linear intrameniscal signal intensity on MR images is highly unlikely to resolve and should be considered a risk factor for medial degenerative meniscal tear.

© RSNA, 2015

Introduction

The main function of the menisci is load distribution (1–3). The medial meniscus has less mobility and absorbs more force during weight bearing compared with the lateral meniscus (4,5). Pathologic abnormalities of the medial meniscus are commonly observed on magnetic resonance (MR) images in persons with or those without knee osteoarthritis (OA) (6–11). Generally, longitudinal meniscal tears are considered to be of traumatic origin (12,13), whereas horizontal, oblique, and complex tears are mostly categorized as degenerative (12,14). In recent years, evidence has emerged that degenerative tears are strongly associated with OA and seem to represent an early preradiographic disease (15–18). Increased intrameniscal signal intensity, not fulfilling the criteria for a meniscal tear according to the “two-slice-touch” rule, is also a frequent finding on MR images (19,20). There is still substantial paucity of scientific evidence of the natural history of such intrameniscal signal intensity (19). Hence, we need to improve our knowledge about the nature of these commonly encountered meniscal changes. These may hypothetically be part of an early OA process leading to meniscal tear and other OA-related changes such as subchondral bone marrow lesions (18,21). Knee OA is a rapidly growing threat to public health and burden on health care (22,23).

Using a longitudinal study design, we aimed to gain new insights into the natural history of intrameniscal signal intensity on MR images in the medial compartment in a large cohort of middle-aged subjects without OA followed for more than 6 years. The main objectives were to determine (a) whether medial linear intrameniscal signal intensity is mainly unidirectional, that is, progressive in nature and (b) if the medial menisci with intrameniscal linear signal intensity are more likely to develop a tear over time compared with menisci without intrameniscal signal intensity, as the reference.

Materials and Methods

Study Sample

Subjects were drawn from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) database. Details for this multicenter longitudinal observational study are available for public access at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu/. Our criteria for sampling were (a) age 45–55 years; (b) no evidence of radiographic tibiofemoral OA based on the central readings performed at the study entry (weight-bearing fixed-flexion posterior-anterior knee radiographs, Kellgren and Lawrence grade 0 in both knees); and (c) available MR images at baseline and at 24-, 48-, and 72-month follow-up for both knees. The subjects were drawn from the OAI incidence, progression, and the “non-exposed” reference cohorts. The subjects in the incidence and progression cohort have the presence of risk factors for OA such as overweight, previous knee trauma and/or surgery, family history of total knee joint replacement, presence of Heberden nodes, and repetitive knee bending. The reference cohort had no risk factors, knee pain, or stiffness in the past year before the baseline examination.

A total of 340 subjects met the criteria. However, we wanted to study subjects who were free of meniscal pathologies in medial compartment in both knees at baseline. Based on our readings, 71 subjects had medial meniscal tear in either knee at baseline and were therefore excluded. Hence, 269 subjects were included for analysis (220 subjects from the incidence cohort, nine from the progression cohort, and 40 from the reference cohort). Due to the relatively low frequency of meniscal changes in the lateral compartment, our present report deals only with the medial meniscus, but we include key descriptive statistics for changes in the lateral meniscus in Appendix E1 (online).

The OAI has been approved by the institutional review boards for the University of California, San Francisco and the four OAI clinical centers (University of Pittsburgh, Ohio State University, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island). All subjects have given informed consent to participate in the study.

MR Imaging Protocol and Meniscal Assessment

The baseline (enrolment 2004 to 2006) and 24-, 48-, and 72-month follow-up images of subjects’ both knees were obtained at the four clinical study centers by using a 3.0-T MR imaging system (Siemens Trio; Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) and quadrature transmit-receive extremity radiofrequency coils. For meniscal assessment, we used coronal intermediate-weighted turbo spin-echo (repetition time msec/echo time msec, 3700/29; echo train length, seven; section thickness, 3 mm; in-plane resolution, 0.37 × 0.46 mm) and sagittal intermediate-weighted fat-saturated (3200/30; echo train length, five; section thickness, 3 mm; in-plane resolution, 0.36 × 0.51 mm) images (24).

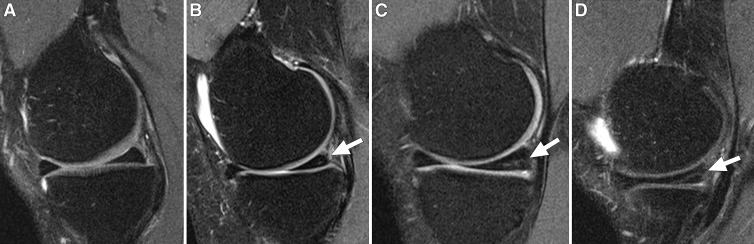

One radiologist (J.K., with 7 years of experience with musculoskeletal MR imaging) who was blinded to subject characteristics, read the images with known time sequence for meniscal integrity in the anterior horn, body, and posterior horn of both knees. The intrameniscal signal intensity was classified as follows: grade 0, no intrameniscal signal intensity; grade 1, one or several areas of punctuate or globular intrameniscal signal intensity; grade 2, linear intrameniscal signal intensity that does not reach the meniscal surface; grade 3, linear signal intensity that reaches the surface on one image section only (Fig 1) (25,26). We considered a definite linear intrameniscal signal intensity to be present if it was graded as 2 or 3. The increased meniscal signal intensity was classified as meniscal tear when it communicated with the superior, inferior, or free edge of the meniscal surface on at least two consecutive images (20). Tears were further classified as longitudinal (including bucket-handle tears), radial, horizontal, oblique (parrot-beak), or complex (27). We considered linear intrameniscal signal intensity to have progressed to meniscal tear if the incident tear occurred in the same subsegment (anterior horn, body, and/or posterior horn) as the preceeding linear intrameniscal signal intensity. The anterior horn, body, and posterior horn were differentiated as anterior one-third, middle one-third, and posterior one-third of the meniscus.

Figure 1:

Sagittal intermediate-weighted fat-saturated MR images of the medial meniscus from four study participants demonstrate different grades of intrameniscal signal intensity in the posterior horn. A, Normal morphology of the medial meniscus. B, Focal grade 1 signal intensity (arrow) in the posterior horn of medial meniscus. C, Linear grade 2 signal intensity (arrow) not extending to the surface of the meniscus. D, Linear grade 3 signal intensity (arrow) involving the inferior surface of the posterior horn on only one image section.

For determination of interobserver reliability, both knees of 30 randomly selected subjects were reassessed by a second reader (F.W.R.), who is an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist with 13 years of experience in standardized semiquantitative assessment. Intraobserver reliability (weighted-κ coefficient) for the meniscal signal intensity and tear at 72 months was 0.91 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.84, 0.96). The interobserver reliability for the readings of the meniscal signal intensity and tear on the segment level (weighted κ) was 0.68 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.80).

Knee Injury Assessment and Knee Surgeries

At each follow-up visit, patients completed self-reported questionnaires. To assess knee injury and/or surgery during follow-up, we used an affirmative answer (yes) to either of the following questions: “Since your last annual visit to the OAI clinic about 12 months ago, have you injured your right (left) knee badly enough to limit your ability to walk for at least two days?” and “Since your last annual visit to the OAI clinic about 12 months ago, did you have surgery or arthroscopy on your right (left) knee?”

Statistics

We present the descriptive data as numbers and percentages for meniscal signal intensity and tear separately for study subjects and the studied knees. To estimate the hazard ratio of developing meniscal tear with and without previous intrameniscal signal intensity, we used the random-effect complementary log-log model. The analysis unit was meniscus segment (body or posterior horn). The anterior horn was excluded from the analysis due to very low number with intrameniscal signal intensity during the course of the study (n = 6 and no incident meniscal tears). Although the anatomic changes in the knee are continuous in nature, their presence was assessed at discrete time points (with 2 years between assessments). Thus, we used the complementary log-log model for discrete time to estimate the hazard ratio. The outcome (tear) was assessed at three follow-up times: 24, 48, and 72 months. The end of the follow-up time was either the development of meniscal tear in the same meniscal subsegment or a 72-month follow-up. The linear intrameniscal signal intensity was included in the model as time-dependent covariate, as in some meniscal segments the linear signal intensity was first present after the baseline examination (at 24 or 48 months). We adjusted the analysis for age, sex, body mass index, and knee side. The random intercept on individual level was included in the model to account for the correlation between measurements made in the same person. The result is presented with 95% CIs. The analyses were performed by using statistical software (Stata 2013; Stata, College Station, Tex).

Results

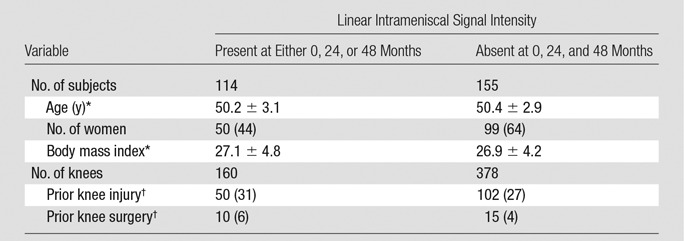

The mean age ± standard deviation of the 269 study subjects (120 men and 149 women) at baseline was 50.3 years ± 3.0, and the mean body mass index was 27.0 ± 4.6. Subjects who had linear intrameniscal signal intensity in one or both knees were more often men, but had similar age and body mass index compared with those without linear intrameniscal signal intensity. There were no essential differences in the frequency of self-reported knee injury or surgery between the knees with and those without linear intrameniscal signal intensity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Study Subjects According to Presence of Linear Intrameniscal Signal Intensity in the Medial Meniscus at 0-, 24-, or 48-month Assessment

Note.—Descriptive data include information from all three meniscal segments (anterior horn, body, and posterior horn). Data in parentheses are percentages.

*Data are means ± standard deviation.

†Data about self-reported prior knee injuryand/or surgery have been collected at baseline and during follow-up until the development of intrameniscal signal intensity.

Linear Intrameniscal Signal Intensity in Medial Meniscus

At baseline, linear intrameniscal signal intensity in the body or posterior horn of the medial meniscus was present in 102 of the 269 subjects (38% of the study sample) and in 140 of all studied knees (n = 538, 26%). Thirty-eight participants (14%) had linear intrameniscal signal intensity in both knees at baseline.

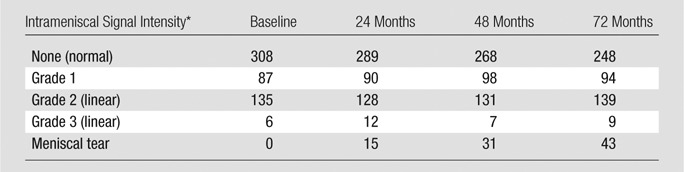

At 72-month follow-up, a total of 114 subjects (42%) and 155 knees (29%) had evidence of linear intrameniscal signal intensity. During follow-up, fewer knees remained free of intrameniscal signal intensity and more knees developed a medial meniscal tear (Table 2, Fig 2). Altogether, 128 of 269 subjects (48%) and 181 of 538 knees (34%) had evidence of linear intrameniscal signal intensity at baseline or 24-, 48-, or 72-month follow-up. Of the knees with linear intrameniscal signal intensity (at any time point), 97% involved the posterior horn and 29% additionally involved the meniscus body. During the 6-year study, we only observed a single medial meniscus (two segments), with regression of linear intrameniscal signal intensity (from grade 2 to 0). Further, there were only 25 medial menisci with linear signal intensity grade 3 at baseline, 24 months, or 48 months. None of these regressed to grade 2 linear signal intensity.

Table 2.

Distribution of the Highest Grade of Increased Intrameniscal Signal Intensity in the Medial Meniscus of Each Knee in 269 Study Subjects

Note.—Data on intrameniscal signal are missing due to poor image quality for two knees at baseline and for four, three, and five knees at 24-, 48-, and 72-month follow-up, respectively.

*Grade 1 = one or several areas of punctuate or globular intrameniscal signal intensities; grade 2 = linear intrameniscal intensity that does not reach to the meniscal surface; grade 3 = linear intensity that reaches the surface on one image section only; meniscal tear = signal that reaches the surface on two or more image sections.

Figure 2:

Schematic of the natural history of linear intrameniscal signal intensity in medial compartment of knees on MR images over 6 years in 269 middle-aged subjects. Linear signal = increased intrameniscal signal intensity on MR images of the knees and is classified as grade 2 or 3, that is, linear signal intensity that does not reach the meniscal surface or reaches the surface only in a single section, respectively. Data on intrameniscal signal intensity is missing for two knees at baseline and for four, three, and five knees at 24-, 48-, and 72-month follow-up, respectively, due to poor image quality. * = One knee with linear intrameniscal signal in the medial compartment developed a meniscal tear in an adjacent subsegment (ie, not connected to the linear signal).

Meniscal Tears

At 72-month follow-up, 34 subjects (13%; 13 women and 21 men) had developed an incident medial meniscal tear in 43 knees (n = 538; 8%). The following tear types were found: 28 knees with horizontal tear, eight knees with oblique tear, six knees with complex tear, and four knees with radial tear. In two knees with a horizontal tear, meniscal destruction (partial loss of the meniscal tissue) was also observed. In three of the 34 subjects, two different types of tears were observed in different parts of the same meniscus. Of the menisci with tears, 25 (58%) were located in the posterior horn only, 17 (40%) involved the posterior horn and the body, and one tear (2%) was confined to the meniscus body.

Meniscal Tears in Relation to Prior Intrameniscal Signal Intensity Change

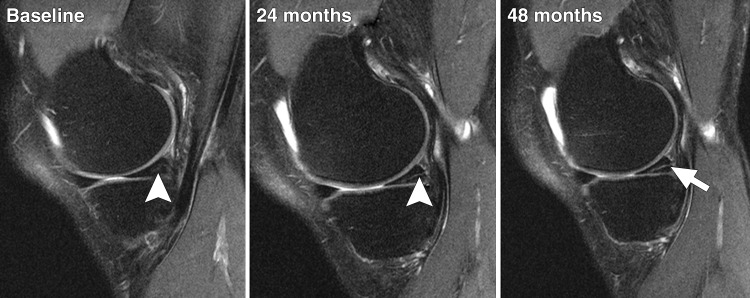

Among knees with linear intrameniscal signal intensity, 31 knees (n = 155; 19%) in 25 subjects (n = 114; 22%) developed a meniscal tear involving the same meniscal segment (Figs 2, 3). In those 31 torn menisci, the following tear types were represented: 25 horizontal, five oblique, and three complex tears (two menisci had multiple tears). One knee with linear intrameniscal signal intensity developed a radial tear in an adjacent segment. Of the 43 knees with meniscal tear, 27 (63%) had linear signal intensity at baseline.

Figure 3:

Longitudinal series of sagittal intermediate-weighted fat-saturated MR images from a study subject exemplify progression of linear intrameniscal signal intensity into a medial meniscal tear over 48 months. Images show intrameniscal signal intensity grade 2 (arrowhead) at baseline, having progressed to grade 3 (arrowhead) at 24-month follow-up. At 48 months, the signal is visible on several sections and indicates a horizontal meniscal tear in the posterior horn (arrow).

On the knee level, there were 31 tears preceded by linear signal intensity, 14 from grade 3 and 17 from grade 2. Eleven knees (3%) in 10 subjects (6%) developed medial meniscal tear without being preceded by linear intrameniscal signal intensity, whereof eight of these knees had grade 1 intrameniscal signal intensity and four knees had no intrameniscal signal intensity in the preceding examination (Fig 2). Among these, we observed three horizontal, three oblique, three complex, and three radial tears (one meniscus had multiple tears).

The incidence of medial meniscal tears during the 24, 48, and 72 months of follow-up in subjects with and those without the preceding linear intrameniscal signal intensity is presented in detail in Appendix E2 (online).

In the multivariable model, the hazard ratio for developing meniscal tear was 18.2 (95% CI: 8.3, 39.8) if linear intrameniscal signal intensity was present, compared with no linear signal intensity.

Knee Injuries and Surgeries

Between baseline and 72-month follow-up, there were 51 persons (n = 269; 19%) with 61 (n = 538; 11%) knees with self-report of knee injury. Of the 43 knees with incidental medial meniscal tear during follow-up, there was only a single knee (2%) for which the subject reported injury in the interval between the MR imaging assessments, when the tear was first observed, and 24 months before.

During follow-up, nine knees (2%) in nine persons (3%) were reported to have had surgery. These knees were primarily not censored as details of the exact type of surgery (procedure and compartment) are unknown. To evaluate the robustness of our results, we performed two sensitivity analyses. First, when these nine knees that underwent surgery were all censored in the multivariable model (from last evaluation before the surgery), the hazard ratio for developing meniscal tear was 18.2 (95% CI: 8.1, 40.8) if intrameniscal signal intensity was present, compared with no linear signal intensity. Second, in the sensitivity analysis, by assuming that all nine knees that underwent surgery did have partial medial meniscectomy due to a tear, the corresponding hazard ratio for developing a tear was 12.0 (95% CI: 6.0, 23.9).

Discussion

We examined the natural history of intrameniscal signal intensity on knee MR images in the medial compartment in subjects aged 45 to 55 years without radiographic evidence of knee OA at baseline. The majority of the study subjects had risk factors for knee OA. The study provides new knowledge that linear intrameniscal signal intensity in this age category is very unlikely to regress. Instead it is associated with increased risk of developing a degenerative meniscal tear in the same meniscal segment. Our study provides evidence in strong support of the fact that most meniscal tears in this cohort were not caused by acute knee trauma but due to slow degradation weakening the meniscus structure into typically a horizontal cleavage or flap tear.

Histologically, intrameniscal signal intensity may represent foci or bands of mucoid degeneration or microcyst formation and separation of collagen bundles (28,29). These changes may weaken the meniscal structure and serve as a risk factor for degenerative meniscal tears (28). According to the prospective MR imaging study conducted by Dillon et al on 27 younger subjects (mean age of 34 years), the intrameniscal signal intensity change remained stable or decreased in size during the mean follow-up period of 27 months (30). Although it is unclear in the report, these subjects may have had knee trauma, which suggests another origin of the signal than degeneration. In another longitudinal study no association was reported between intrameniscal signal intensity and incident meniscal tears over 12 months in 161 women aged 40 years or older (19). The few previous studies have not supported the hypothesis that intrameniscal signal intensity progresses to a tear. However, the smaller sample sizes, subject selection that included younger subjects after knee trauma, and short follow-up intervals might have influenced the results, as that time frame might not have been enough to fully assess the natural history of meniscal signal for incident degenerative tears.

We observed that linear intrameniscal signal intensity was frequently encountered in subjects between 45 and 55 years of age. At baseline, linear intrameniscal signal intensity was present in 26% of knees. The high prevalence is in line with that in earlier reports of subjects of about the same age (19). With use of a much longer follow-up period than in earlier studies, the linear intrameniscal signal intensity was not likely to resolve over time but was prone to progress to a meniscal tear. Of the 160 knees with linear intrameniscal signal intensity until 48 months of follow-up, 19% (31 knees) developed an incident meniscal tear in the same segment. The majority of those tears were horizontal or oblique tears in the posterior horn and/or body, thus considered being of degenerative character. The corresponding number of knees with incident meniscal tears over 6-year follow-up without previous intrameniscal signal intensity was only 3% (11 knees). We found that the hazard ratio for developing an incident medial meniscal tear over time was 18 times higher if there was previous intrameniscal signal intensity present at the same segment. There was only one subject reporting knee trauma prior to tear detection. Altogether, these findings provide new strong evidence in support that meniscal tears were not typically the consequence of acute traumatic events, but rather a slow degenerative process. The exact time frame for the development of an actual degenerative tear from no intrameniscal signal intensity remains unclear as most subjects who developed a tear had intrameniscal signal intensity already at baseline.

Degenerative meniscal tears are common in persons over 45 years of age, both with or without radiographic knee OA (10,11). Such tears are highly associated with increased risk of developing radiographic knee OA (18,21). Hence, we hypothesize that intrameniscal signal intensity may signal a degenerative process in the knee long before the disease is evident radiographically. The present study has limitations. We focused on the medial compartment since meniscus damage is two to three times as frequent there than in the lateral compartment (7). Still, we include lateral compartment data in Appendix E1 (online). There was neither arthroscopic nor pathologic correlation available for the verification of the MR imaging–detected meniscal tears. However, arthroscopy is not ethical and feasible in large population-based studies. Nevertheless, the use of the two-slice touch rule has been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity (20). The meniscal integrity was assessed on MR images with known time sequence for the reader, which might have created a potential bias. However, it has been shown that the sensitivity of recognizing the relatively minor changes in OA-affected tissues over time is substantially increased if the temporal sequence is known and has been recommended as a preferred approach for longitudinal OA studies (31–33). We selected OAI study subjects without radiographic knee OA as we were interested in capturing early morphologic changes in the meniscus before radiographic manifestation of OA. Although we find it highly likely that increased risk of degenerative tear (if linear intrameniscal signal intensity is present) will hold true also for knees with radiographic OA, it still remains to be proven. Finally, further validation studies would be useful to verify our results.

In conclusion, we found that linear intrameniscal signal intensity is a frequent finding in the medial meniscus on knee MR images in subjects between 45 and 55 years of age without radiographic knee OA but with risk factors for OA. Such intrameniscal signal is highly unlikely to resolve with time. On the contrary, linear signal intensity is prone to progress to a degenerative meniscal tear and may therefore play a crucial part in the early preradiographic knee OA (18).

Advances in Knowledge

■ The presence of intrameniscal linear signal intensity on MR images of the medial meniscus in middle-aged persons (the majority with risk factors for knee osteoarthritis [OA]) is likely to evolve into a degenerative meniscal tear (hazard ratio, 18.2; 95% confidence interval: 8.3, 39.8) compared with no linear signal intensity.

■ Medial meniscal tear in middle-aged persons (the majority with risk factors for knee OA) is often a result of slowly developing meniscal degradation rather than acute knee trauma.

■ In our prospective sample of subjects without radiographic evidence of OA followed for more than 6 years (with knee MR imaging performed at four time points), only one of the 43 incident medial meniscal tears was associated with a self-report of acute knee injury.

■ Our findings are in strong support of prior reports that degenerative meniscal tears are often incidental findings on knee MR images.

Implication for Patient Care

■ In middle-aged and elderly patients with risk factors for knee OA, linear intrameniscal signal intensity may be considered a risk factor for medial degenerative meniscal tear and thus signal intensity may be considered a risk factor of future OA development.

APPENDIX

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the OAI for the free use of public access data. We would also like to acknowledge the support from Osteoarthritis Research Society International and the scholarship which made it possible for Jaanika Kumm to come to Lund University to perform the study. The OAI is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258, N01-AR-2-2259, N01-AR-2-2260, N01-AR-2-2261, N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public use data set and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners.

Received December 17, 2014; revision requested February 24, 2015; revision received April 25; accepted May 5; final version accepted May 8.

Supported by the Swedish Research Council, Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI, young investigator travel award), Kock Foundations, Region Skåne, and the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants N01-AR-2-2258, N01-AR-2-2259, N01-AR-2-2260, N01-AR-2-2261, and N01-AR-2-2262).

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: J.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. F.W.R. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: CMO and shareholder in Boston Imaging Core Lab. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. A.G. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: personal fees from Boston Imaging Core Lab, MerckSerono, TissueGene, OrthoTrophix, and Genzyme. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. A.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.E. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: received payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from Ossur and payment for travel expenses as board member of OARSI. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- OA

- osteoarthritis

- OAI

- Osteoarthritis Initiative

References

- 1.Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A. Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8(7):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seedhom BB, Dowson D, Wright V. Proceedings: functions of the menisci–a preliminary study. Ann Rheum Dis 1974;33(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker PS, Erkman MJ. The role of the menisci in force transmission across the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1975;(109):184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa CR, Morrison WB, Carrino JA. Medial meniscus extrusion on knee MRI: is extent associated with severity of degeneration or type of tear? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vedi V, Williams A, Tennant SJ, Spouse E, Hunt DM, Gedroyc WM. Meniscal movement: an in-vivo study using dynamic MRI. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999;81(1):37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rytter S, Jensen LK, Bonde JP, Jurik AG, Egund N. Occupational kneeling and meniscal tears: a magnetic resonance imaging study in floor layers. J Rheumatol 2009;36(7):1512–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2008;359(11):1108–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaPrade RF, Burnett QM, 2nd, Veenstra MA, Hodgman CG. The prevalence of abnormal magnetic resonance imaging findings in asymptomatic knees: with correlation of magnetic resonance imaging to arthroscopic findings in symptomatic knees. Am J Sports Med 1994;22(6):739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, et al. A prospective and blinded investigation of magnetic resonance imaging of the knee: abnormal findings in asymptomatic subjects. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;(282):177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guermazi A, Niu J, Hayashi D, et al. Prevalence of abnormalities in knees detected by MRI in adults without knee osteoarthritis: population based observational study (Framingham Osteoarthritis Study). BMJ 2012;345:e5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding C, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, et al. Meniscal tear as an osteoarthritis risk factor in a largely non-osteoarthritic cohort: a cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol 2007;34(4):776–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metcalf MH, Barrett GR. Prospective evaluation of 1485 meniscal tear patterns in patients with stable knees. Am J Sports Med 2004;32(3):675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camanho GL, Hernandez AJ, Bitar AC, Demange MK, Camanho LF. Results of meniscectomy for treatment of isolated meniscal injuries: correlation between results and etiology of injury. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2006;61(2):133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poehling GG, Ruch DS, Chabon SJ. The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clin Sports Med 1990;9(3):539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes CW, Jamadar DA, Welch GW, et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee: comparison of MR imaging findings with radiographic severity measurements and pain in middle-aged women. Radiology 2005;237(3):998–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Englund M, Guermazi A, Lohmander SL. The role of the meniscus in knee osteoarthritis: a cause or consequence? Radiol Clin North Am 2009;47(4):703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Englund M. Meniscal tear: a feature of osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 2004;75(312):1–45, backcover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englund M, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, et al. Meniscal tear in knees without surgery and the development of radiographic osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly persons: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60(3):831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crema MD, Hunter DJ, Roemer FW, et al. The relationship between prevalent medial meniscal intrasubstance signal changes and incident medial meniscal tears in women over a 1-year period assessed with 3.0 T MRI. Skeletal Radiol 2011;40(8):1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Smet AA, Tuite MJ. Use of the “two-slice-touch” rule for the MRI diagnosis of meniscal tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187(4):911–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Englund M, Felson DT, Guermazi A, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscal pathology on knee MRI in older US adults: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70(10):1733–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(7):1323–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turkiewicz A, Petersson IF, Björk J, et al. Current and future impact of osteoarthritis on health care: a population-based study with projections to year 2032. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22(11):1826–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16(12):1433–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crues JV, 3rd, Mink J, Levy TL, Lotysch M, Stoller DW. Meniscal tears of the knee: accuracy of MR imaging. Radiology 1987;164(2):445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodler J, Haghighi P, Pathria MN, Trudell D, Resnick D. Meniscal changes in the elderly: correlation of MR imaging and histologic findings. Radiology 1992;184(1):221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jee WH, McCauley TR, Kim JM, et al. Meniscal tear configurations: categorization with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180(1):93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoller DW, Martin C, Crues JV, 3rd, Kaplan L, Mink JH. Meniscal tears: pathologic correlation with MR imaging. Radiology 1987;163(3):731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajek PC, Gylys-Morin VM, Baker LL, Sartoris DJ, Haghighi P, Resnick D. The high signal intensity meniscus of the knee: magnetic resonance evaluation and in vivo correlation. Invest Radiol 1987;22(11):883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillon EH, Pope CF, Jokl P, Lynch JK. Follow-up of grade 2 meniscal abnormalities in the stable knee. Radiology 1991;181(3):849–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross PD, Huang C, Karpf D, et al. Blinded reading of radiographs increases the frequency of errors in vertebral fracture detection. J Bone Miner Res 1996;11(11):1793–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felson DT, Nevitt MC. Blinding images to sequence in osteoarthritis: evidence from other diseases. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009;17(3):281–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roemer FW, Nevitt MC, Felson DT, et al. Predictive validity of within-grade scoring of longitudinal changes of MRI-based cartilage morphology and bone marrow lesion assessment in the tibio-femoral joint: the MOST study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012;20(11):1391–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.