Summary

OprG is an outer membrane protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa whose function as an antibiotic-sensitive porin has been controversial and not well defined. Circumstantial evidence led to the proposal that OprG might transport hydrophobic compounds by using a lateral gate in the barrel wall thought to be lined by three conserved prolines. In order to test this hypothesis and to find the physiological substrates of OprG, we reconstituted the purified protein into liposomes and found it to facilitate the transport of small amino acids like glycine, alanine, valine, and serine, which was confirmed by Pseudomonas growth assays. The structures of wild-type and a critical proline mutant were determined by NMR in dihexanoylphosphatidylcholine micellar solutions. Both proteins formed 8-stranded β-barrels with flexible extracellular loops. The interfacial prolines did not form a lateral gate in these structures, but loop 3 exhibited restricted motions in the inactive P92A mutant but not in wild-type OprG.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium commonly found in many natural and man-made environments. It can utilize various sources of carbon, which contributes to its ecological success. P. aeruginosa is also a serious opportunistic human pathogen and the most common cause of lung infections in cystic fibrosis patients (Govan et al., 2007; Rajan and Saiman, 2002). Moreover, P. aeruginosa is responsible for staggering numbers of nosocomial infections in hospital environments, including urinary tract, burn, and wound infections. Pseudomonal infections are difficult to treat because of the bacterium's ability to form biofilms that are highly resistant to many common antibiotics. This extraordinary antibiotic resistance is partially imparted by a very stable outer membrane (OM) with a permeability to small molecules that is much lower than that of most other Gram-negative bacteria (Delcour, 2009). Complex lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in the OM and divalent cation-mediated LPS interactions contribute to the extraordinary stability of pseudomonal OMs towards adverse environmental conditions.

About 30 different outer membrane proteins (OMPs) transport a variety of substrates across the OM of P. aeruginosa (Hancock and Brinkman, 2002; Tamber et al., 2006). Unlike in E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria, no general non-specific porins appear to exist in the OM of Pseudomonas. Rather, specific porins (named Opr in Pseudomonas) for the required substrates have evolved. Owing to the highly polar saccharide layer of LPS, the OM forms an efficient barrier not only to water-soluble substrates, but also to hydrophobic compounds. Because Pseudomonas can grow on a variety of different substrates, it has developed transport methods for polar, apolar, and charged molecules (Mesaros et al., 2007).

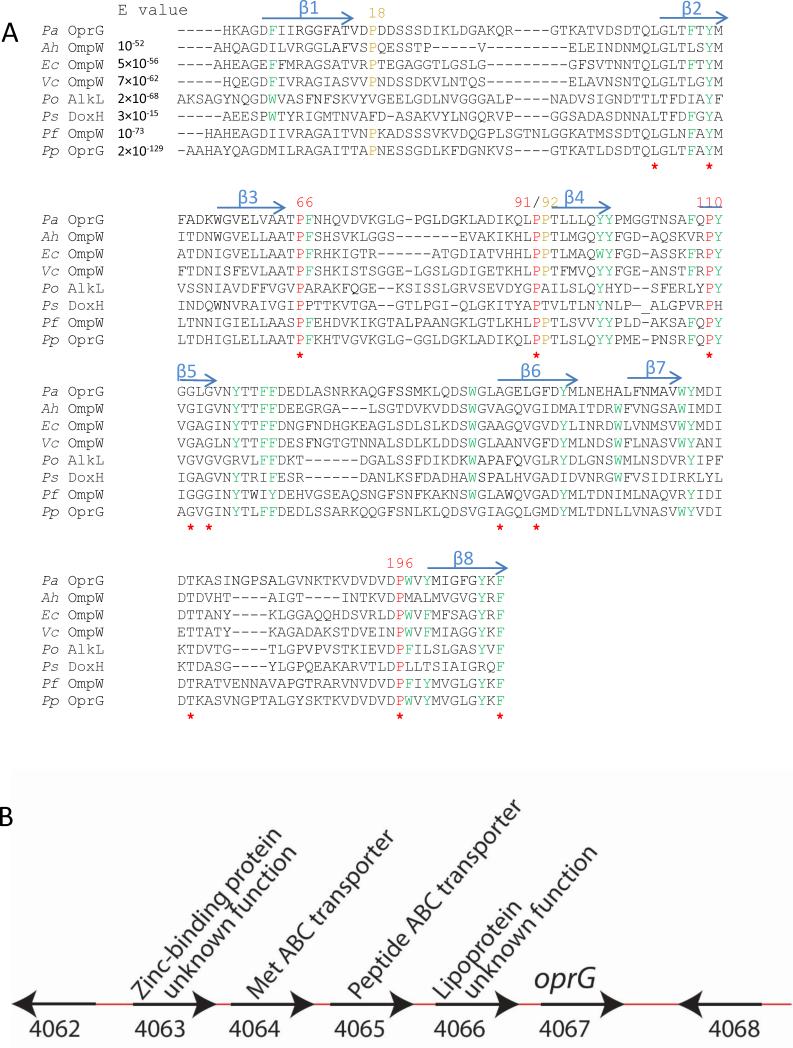

One of the smaller Pseudomonas porins is OprG, which forms an 8-stranded β-barrel in the OM (McPhee et al., 2009; Touw et al., 2010). OprG is a member of the widely distributed, but still poorly characterized OmpW family of OMPs. Possible functions of OmpW family members include osmoregulation (Wu et al., 2006), adaptive responses to environmental conditions (Nandi et al., 2005), and uptake of naphthalene and other polycyclic aromatic compounds (Neher and Lueking, 2009). Even though the substrate specificity of OprG has not been previously characterized in much detail, an analysis of close homologs (Figure 1A) suggests possible functions. OprG from P. putida, which is 70% identical to P. aeruginosa OprG, is a protein of high emulsifying activity and may be involved in the transport of hydrocarbons (Walzer et al., 2009). OprG has 23% sequence homology with NahQ, a protein involved in dibenzothiophene and naphthalene catabolism in several species of Pseudomonas (Denome et al., 1993). OprG has also been hypothesized to facilitate Pseudomonas infections. For example, oprG-deficient strains of P. aeruginosa are significantly less cytotoxic to human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells than wild-type strains (McPhee et al., 2009). Wild-type P. aeruginosa causes 42% HBE cells to lyse after a 4 hour incubation, while an oprG-deficient strain shows only 1% cell lysis, suggesting that OprG plays a role at some early stage of pathogen-cell interaction.

Figure 1. ClustalW alignment of OprG and closely related OmpW family members (A) and genomic context of oprG (B).

A: The observed β-strands of OprG are shown above the alignment as blue arrows. All completely conserved residues are marked with a red star, fully conserved prolines are colored red, partially conserved prolines are colored orange, fully and partially conserved aromatic residues are colored green. The following OmpW family members have been used: Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa OprG; Ah, Aeromonas hydrophila OmpW; Ec, E. coli OmpW; Vc, Vibrio cholerae OmpW; Po, Pseudomonas oleovorans AlkL; Ps, Pseudomonas sp. (strain C18) DoxH; Pf, Pseudomonas fluorescens OmpW; Pp, Pseudomonas putida OprG. The expect values (E) were calculated using The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). B: Functional genes are indicated by the black arrows. Numbers below the graph indicate gene locus tags. Predicted function of the genes are indicated above the graph. See also Figure S1.

The crystal structure of P. aeruginosa OprG reveals an 8-stranded β-barrel with four long extracellular loops, three short periplasmic turns, and an internal core lined with many apolar residues (Touw et al., 2010), i.e., its architecture closely resembles that of its E. coli homolog OmpW (Hong et al., 2006). OprG features an interesting lateral opening in the barrel wall that is formed by three conserved prolines, Pro66, Pro91, and Pro92, which are all placed near the extracellular hydrophilic-hydrophobic interface of the OM (Figure S1A). Touw et al (Touw et al., 2010) hypothesized that this opening may serve as a lateral gate for the escape of small hydrophobic molecules from the polar LPS-penetrating portion of OprG into the hydrocarbon layer of the OM in a fashion similar to a mechanism that has been proposed for the FadL-mediated transport of fatty acids in E. coli (Hearn et al., 2009; van den Berg, 2005). However, the transport of apolar compounds by OprG has so far not been demonstrated.

To investigate the substrate specificity of OprG and to test the lateral gate hypothesis of apolar substrate release into the lipid bilayer, we conducted comprehensive liposome-swelling and bacterial growth assays with a large panel of potential substrates. Despite previous claims that OprG might function as a transporter for hydrophobic compounds, we discovered that it forms a channel for the transport and uptake of small amino acids including glycine, alanine, valine, serine, and threonine. The mutation of the conserved Pro92 to an alanine resulted in a loss of the transport function, while mutations of Pro66 and Pro91 affected the ability of the protein to insert into membranes. In order to obtain insight into the mechanistic and structural roles of these conserved prolines, we solved by NMR spectroscopy the dynamic structure of the P92A mutant of OprG and compared it with the dynamic structure of wild-type OprG in dihexanoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DHPC) micelles. We found that the loops are dynamically disordered in the mutant and wild-type proteins, but that the height of the barrel wall and the loop dynamics are much more asymmetric in the mutant than in wild-type OprG. Possible roles for the function of the proline-rich cluster of OprG to facilitate transport of small amino acids across the OM are discussed.

Results

OprG expression and refolding

OprG was overexpressed in E. coli with a C-terminal His-tag and with its signal sequence deleted as described in Experimental Procedures. This protein, which expressed into inclusion bodies in high yields, was purified by affinity chromatography in a urea-denatured form and refolded by dilution of the denaturant in the presence of DHPC micelles. Wild-type OprG was quantitatively refolded as seen from the shift of its apparent molecular mass (Figure S1B). To investigate the properties of the proline-rich putative lateral gate we mutated prolines 66, 91, and 92 to alanines to obtain the single mutants P66A, P91A, and P92A and the double mutant PP91/92AA. All mutants showed good expression and their refolding was as efficient as that of wild-type OprG (Figure S1B).

Liposome-swelling assay

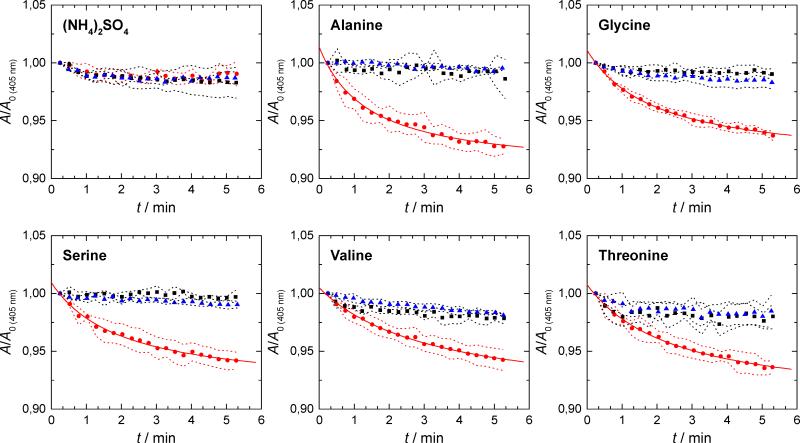

A liposome-swelling assay was used to test the OprG-mediated permeation of small molecules across the liposomal membrane. A wide range of low-molecular weight compounds was tested, including sugars, amino acids, aliphatic alcohols and fatty acids, some other apolar compounds, several common antibiotics, and inorganic salts, but liposome swelling was only observed with the small amino acids glycine, alanine, serine, threonine and valine (Figure 2, Table S1). The swelling assay showed that the OprG-mediated permeation of alanine (relative rate 1.00) was most efficient and that of valine (0.43) was least efficient, while threonine (0.77), glycine (0.82), and serine (0.53) exhibited intermediate permeation rates. No liposome swelling was observed in the absence of OprG and, hence, these same amino acids do not permeate through pure lipid bilayers (black squares in Figure 2). Although the P92A mutant was well folded and readily incorporated into liposomes as demonstrated by SDS-PAGE, it did not facilitate the permeation of any of the tested substrates into the liposomes (blue triangles in Figure 2). The P66A, P91A and PP91/92AA mutants refolded well in DHPC, but these proteins did not insert in sufficient amounts into the liposomes. Therefore, these mutants could not be tested for amino acid permeation using the liposome-swelling assay.

Figure 2. Liposome-swelling assay of OprG.

Liposome-swelling assay with reconstituted wild-type (red dots) and P92A OprG (blue triangles) in the presence of ammonium sulfate and various amino acids. Substrate uptake was observed for alanine, glycine, valine, serine, and threonine, but not for (NH4)2SO4. Pure lipid liposomes (black squares) were used as controls. Data is presented as mean ± SD (dashed line) of at least three independent preparations. Solid lines denote fits of theoretical swelling function where applicable (Bangham et al., 1967). See also Table S1.

Cell growth

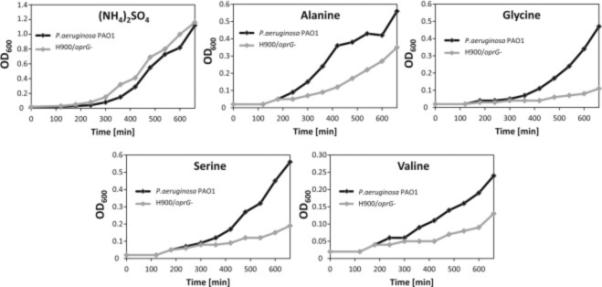

To confirm the results of the liposome-swelling assay, we tested the growth of P. aeruginosa with wild-type OprG and a strain of P. aeruginosa (H900), in which the oprG-gene was disrupted, under conditions where the selected small amino acids provided the only sources of nitrogen. P. aeruginosa can utilize alanine as the source of nitrogen and carbon, but glycine, valine, serine and threonine can be used as sources of nitrogen only (Johnson et al., 2008). To this end, we measured cell growth in minimal media that were supplemented with the amino acids of interest at 2-50 mM concentrations. Optimal substrate concentrations, at which the loss of OprG would compromise growth most, were determined for each amino acid. Although the growth kinetics in these cultures were somewhat variable from day to day, differences between OprG+ and OprG− strains were always observed as reported. Representative growth curves of three separate experiments for each tested amino acid are shown in Figure 3. The difference in growth between OprG+ and OprG− strains appears greatest for glycine and serine and a little less pronounced for valine and alanine. However, in the wild-type strain, growth is most efficient when alanine is used as the single nitrogen source, which is consistent with alanine permeating best through OprG in the liposome-swelling assay (Table S2). No growth defect of the OprG− strain was observed when ammonium sulfate was used as the sole source of nitrogen, confirming that the facilitation of uptake of the tested amino acids by OprG is physiological. Growth on threonine was extremely slow, even when threonine was supplied in concentrations greater than 50 mM. Therefore, threonine may not be a physiological substrate for OprG-mediated permeation although utilization of threonine as a sole nitrogen source could also be metabolically inefficient.

Figure 3. Growth phenotypes of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and an OprG- mutant.

Cells were grown in BM2 minimal media supplemented with putative substrates of OprG as the sole nitrogen sources. The nitrogen sources include 10 mM (NH4)2SO4 (control), 2 mM alanine, 10 mM glycine, 10 mM serine, or 50 mM valine. Data shown are representatives of at least three independent experiments. See also Table S2.

Solution structures of wild-type and P92A OprG in DHPC micelles

To determine the solution structures of wild-type and P92A OprG, 2H,13C,15N-labeled proteins were overexpressed in E. coli, purified, and refolded in DHPC micelles as described in Experimental Procedures. The 15N-1H TROSY-HSQC spectrum of 2H-,13C-,15N-labeled wild-type OprG shown in Figure 4 displayed good dispersion in the proton dimension from 8.5 to 9.5 ppm, indicating well-formed secondary structure. A larger number of cross-peaks overlapped in the 7.8 to 8.5 ppm region suggesting the additional presence of significant regions of disordered residues in the protein. P92A OprG also showed very high quality TROSY spectra and a 2H,13C,15N-labeled sample was used for assignment and structure determination (Figure S2A). However, the 15N-1H TROSY spectra of the other 15N-labeled proline mutant samples were of substantially poorer quality. In the case of P66A, only a few high-field peaks of very low intensity were visible (Figure S2B). Analysis of the TROSY spectrum of P91A revealed no visible high-field peaks, even when increasing the contour scale (Figure S2C). Compared to P92A (Figure S2D), only approximately 40 cross-peaks were present in the PP91/92AA spectrum (Figure S2E).

Figure 4. 15N-1H TROSY spectrum of 2H-,13C-,15N-labeled OprG in DHPC micelles collected at 800 MHz and 45 °C.

The refolded protein sample was exchanged into 25 mm NaPO4 at pH 6.0, 50 mm KCl, 0.05% NaN3, and 5% D2O before being concentrated to ~1.0 mM for NMR experiments. See also Figure S2.

In order to assign the H, N, Cα, Cβ, and CO resonances TROSY-based triple resonance NMR experiments were performed on the 2H-,13C-,15N-labeled wild-type and P92A samples to establish their through-bond connectivities. For wild-type HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(CA)CB, HN(COCA)CB, HNCO, and HN(CA)CO and for P92A HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCB and HNCO spectra were collected. To help the assignment process we also prepared specifically 15N-labeled Phe and Ile samples of wild-type and specifically 15N-labeled Asp, Phe, Val, Leu, and Ile samples of P92A OprG. Using this approach, 90% (77%) of the N and H, 93% (81%) of the Cα, 92% (81%) of the Cβ, and 92% (81%) of the CO resonances of wild-type (and P92A) OprG were assigned. The larger numbers of missing resonances in P92A are presumably due to more line broadening by intermediate exchange in P92A compared to wild-type. Several residues, which showed weak cross-peaks in the wild-type were missing in the P92A 15N-1H TROSY spectrum, including A14, T15, G34-K36, T43, N68-K74, G77, G79, G82-L90, E124, S128, N129, K139-Q141, K174-S176, S181, T188, K89, V194, D195, I201. The lack of these resonances gives the impression of a better dispersion in the 6.8 to 7.5 ppm region of the P92A compared to the wild-type spectrum. On the other hand, several residues that remained unassigned in wild-type could be assigned in P92A. These include Y118, T119, L146-G148, W167-I171. In summary, complete backbone chemical shift assignments were obtained for 181 of the 209 residues of wild-type OprG. Partial assignments were obtained for 14 additional residues, including 6 of the 7 prolines. 14 residues remained unassigned. In the case of P92A, complete backbone assignments were obtained for 152 residues, partial assignments for 19 residues including 4 of the 7 prolines, and 38 residues remained unassigned.

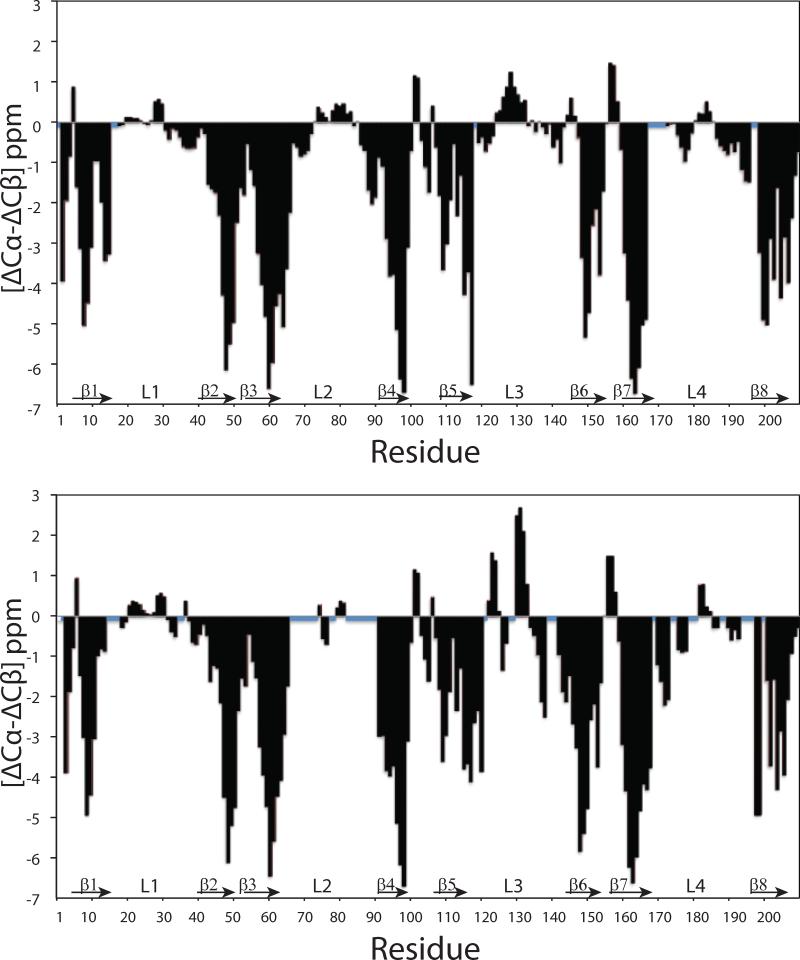

Figure 5 shows the secondary Cα and Cβ chemical shifts along the sequences of both proteins. Eight distinct regions of large negative values typical of β-strands (Metzler et al., 1993) are clearly evident in both cases. These eight putative β-strands are separated by regions with values around zero that are typical for turns and disordered structures. 15N-edited 15N-1H-1H NOESY-TROSY and 15N-1H-15N HSQC-NOESY-HSQC experiments were performed to measure NOEs and to generate structural distance constraints. Acquisition of the two types of NOESY spectra helped reduce ambiguities resulting from peak overlaps. For wild-type (P92A) OprG 232 (145) and 263 (154) peaks were assigned and integrated in the 15N-1H-1H NOESY-TROSY and 15N-15N-1H HSQC-NOESY-HSQC spectra, respectively. Characteristic HN–HN inter-strand NOEs identified the antiparallel orientation of the strands and established the closed β-barrel topology of both proteins. The topologies of the two proteins derived from chemical shifts and observed long-range NOEs leading to inter-strand hydrogen bonds as well as a representation of their assigned residues are summarized in Figures 6A and B. In summary, wild-type and P92A OprG displayed similar patterns of long-range NOEs confirming their similar overall β-barrel structures.

Figure 5. Three-bond averaged secondary chemical shifts of OprG (A) and P92A OprG (B) in DHPC micelles.

The secondary chemical shifts, where the deviation (Δ) of each residue-specific Cα and Cβ chemical shift from random coil values was determined as (ΔCα − ΔCβ) = 1/3 (ΔCαi−1 + ΔCα + ΔCαi+1 − ΔCβi−1 − ΔCβi − ΔCαi+1), are plotted as a function of the amino acid sequence. Large negative values indicate β-sheet secondary structure, while large positive values indicate α-helical structure. Blue squares denote unassigned residues. Chemical shifts were corrected for both deuteration and TROSY effects prior to analysis.

Figure 6. Schematic topologies of OprG (A) and P92A OprG (B) and 2H/1H exchange experiments of OprG (C) and P92A OprG (D).

A and B: Residues that were partially assigned are colored light gray, and residues that were completely unassigned are colored dark gray. For all other residues, complete nitrogen, hydrogen, Cα, Cβ, and CO assignments were obtained. Residues that face the lumen of the barrel are colored light blue. β-strand residues are denoted as squares and were determined from the solution structure using the Kabsch and Sander secondary structure algorithm provided with the MOLMOL software package. Loop and turn residues are denoted as circles. Inter-residue lines represent long- and medium-range NOEs observed in NOESY experiments. Hydrogen bond constraints that were identified through 2H/1H exchange experiments are denoted as black inter-residue lines. C and D: D2O was added to lyophilized protein/DHPC samples and 15N-1H TROSY spectra were recorded at 800 MHz and 45°C, 20 min, 4 hours, 1 day, and 1 week after addition of D2O. Resonances that disappeared before recording the first spectra are colored red, resonances present 20 min after D2O addition (but not 1 hour) are colored yellow, resonances present after 4 hours, 1 day, and 1 week are colored green, light blue, and dark blue, respectively. Unassigned residues are colored gray.

Despite their generally similar topologies, there are significant differences between the two proteins. For example, strong NOEs were observed connecting strands 5 to 7 in the upper part of the P92A barrel that were absent in the wild-type. These include NOEs between residues A92-Y118, L94-V116, N117-G145, G115-A147, G148-Y168. Most unassigned residues are found at the barrel-to-loop transitions in the wild-type while they are primarily located in loop 2 and scattered through some of the other loops in P92A. To confirm the presence of inter-strand hydrogen bonds, we performed H/D exchange experiments (Figures 6C and D). The graded H/D exchange revealed very stable β-sheets and highly exchangeable loops for both proteins. The H/D exchange experiments also highlight additional differences between wild-type and P92A OprG. Several residues that were unassigned in the wild-type, but assigned in P92A, proved to be resistant to H/D exchange with 1H signals persisting for at least 20 min (Y118-T120, L146, M169, D170) or even a week (V116, G145, A147, G148, A165, W167, Y168) after transfer into D2O buffer. Some of the additionally assigned residues formed hydrogen bonds between strands 4, 5, 6 and 7 (Figures 6C and D). The H/D exchange data combined with inter-strand NOEs allowed us to generate a total of 106 and 116 hydrogen bond constraints for wild-type and P92A OprG, respectively (Figures 6A and B).

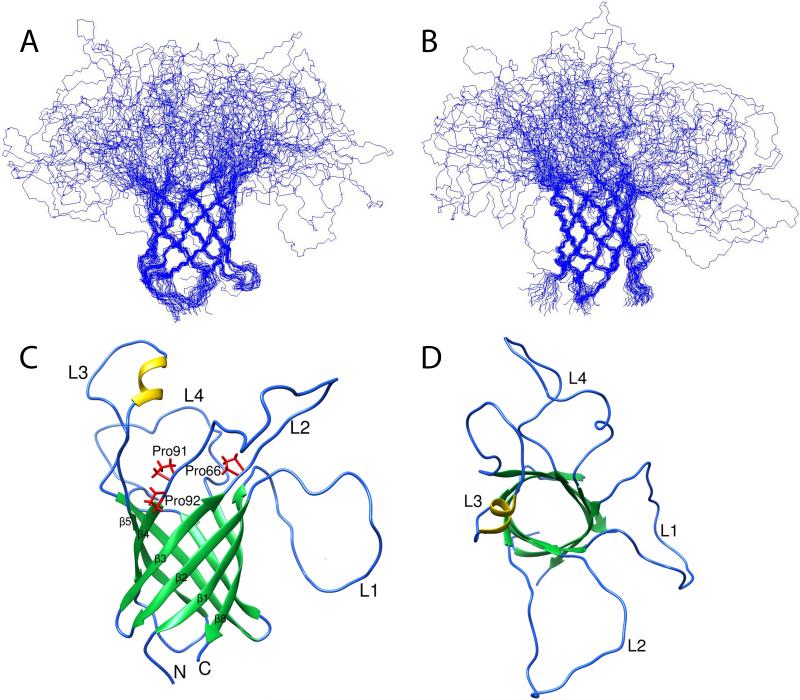

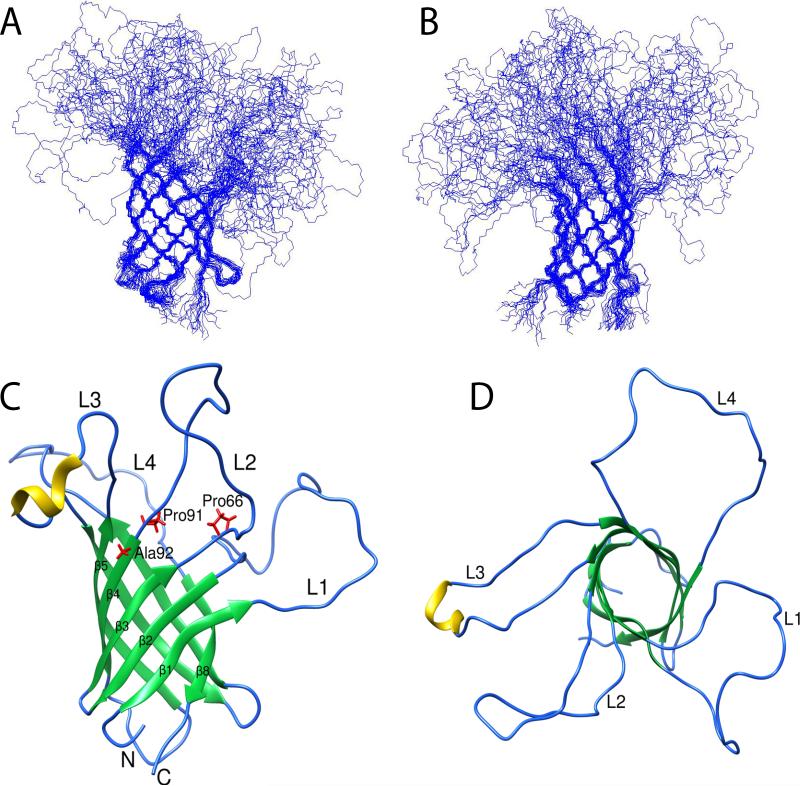

The structures of wild-type (and P92A) OprG in DHPC micelles were calculated based on 185 (139) NOE-derived distance constraints, 180 (224) chemical shift-derived backbone dihedral angle constraints (Cornilescu et al., 1999), and 106 (116) hydrogen bond constraints. As expected, the overall folds of the 20 lowest energy conformers were similar for both proteins. Both formed closed eight-stranded β-barrel structures (Figures 7 and 8). The barrel backbone root mean square deviations (r.m.s.d.'s) of the NMR ensembles were 0.98 ± 0.21 Å for wild-type and 0.89 ± 0.18 Å for the P92A β-barrels (Table 1). When the periplasmic turns are included, the r.m.s.d.'s are 1.19 ± 0.28 Å for wild-type and 1.19 ± 0.32 Å for P92A OprG. The average pairwise r.m.s.d. between the two barrel backbone ensembles is 2.07 ± 0.41 Å. The shear numbers (Schulz, 2002) of both β-barrels are 10 and the β-strand tilt angles to the membrane normal are 43°. The wild-type β-barrel has an average length of 7.9 residues and that of P92A 8.6 residues. Despite these overall similar folds, the two structures showed several significant differences in their local hydrogen bonding patterns and β-barrel lengths. The increased lengths of β-strands 5, 6, and 7 in P92A resulted in a highly asymmetrical barrel wall with a 9.3 residue average length of strands 5 to 7 compared to an average length of 7.3 residues for strands 8 to 4 (Figure 8C). The longer β-strands on taller side of the barrel wall likely also restrict the motions of the loops that are connected to these strands to a greater extent than the motions of the loops that are connected to the shorter side of the barrel wall. In marked contrast, the height of the barrel wall of wild-type OprG is much more uniform (Figure 7C), presumably leading to more similar mobilities of the residues in the four extracellular loops of the wild-type protein.

Figure 7. Solution structure of OprG in DHPC micelles.

A and B: NMR ensemble of the 20 calculated lowest energy structures. Side view (C) and top-down view (D) of the lowest energy conformer of OprG from the ensemble of 20 lowest energy structures. The β-barrel, loop/turn and α-helix regions are colored green, blue, and yellow, respectively, in C and D.

Figure 8. Solution structure of P92A OprG in DHPC micelles.

A and B: NMR ensemble of the 20 calculated lowest energy structures. Side view (C) and top-down view (D) of the lowest energy conformer of P92A OprG from the ensemble of 20 lowest energy structures. The β-barrel, loop/turn and α-helix regions are colored green, blue, and yellow, respectively, in C and D.

Table 1.

NMR and Refinement Statistics for wild-type and P92A OprG Structures in DHPC micellesa

| A. NMR distance and dihedral angle restraints | ||

|---|---|---|

| OprG | P92A | |

| Structure Calculation | ||

| Unique HN-HN NOE distances | 185 | 139 |

| Sequential | 109 | 73 |

| Medium range | 13 | 12 |

| Long Range | 63 | 54 |

| Intramolecular | 0 | 0 |

| Hydrogen bond restraints | 106 | 116 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | 180 | 224 |

| B. Violations | ||

| Distance constraints (Å) | 0.0043± 0.0006 | 0.0081± 0.001 |

| Dihedral angle restraints (°) | 0.0415± 0.0093 | 0.0737± 0.018 |

| Max. distance constraint (>0.2 Å) | 0 | 0 |

| Max dihedral angle (>2.0 Å) | 0 | 0 |

| Deviations from idealized geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.00053±0.00005 | 0.00061±0.00003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.253±0.00086 | 0.257±0.0022 |

| Impropers | 0.0872±0.0031 | 0.0898±0.0066 |

| Ramachandran map analysisb | ||

| Most favored regions | 64.1% | 65.7% |

| Additionally allowed regions | 29.8% | 29.1% |

| Generously allowed regions | 4.0% | 3.2% |

| Disallowed regions | 2.1% | 2.1% |

| C. Ensemble RMSD | ||

| Mean global backbone r.m.s. deviation (Å) | ||

| B-sheet residuesc | 0.98±0.21 | 0.89±0.18 |

| B-sheet and turn residues | 1.19±0.26 | 1.19±0.32 |

| All residues | 10.81±2.05 | 9.76±1.91 |

| Mean global heavy atom r.m.s. deviation (Å) | ||

| B-sheet residues | 1.99±0.27 | 2.16±0.29 |

| B-sheet and turn residues | 2.13±0.31 | 2.30±0.32 |

| All residues | 11.13±1.96 | 10.05±1.77 |

Calculated from the 20 lowest-energy CNS conformers of each of the structures in DHPC micelles

Calculated using PROCHECK-NMR

β-sheet residues defined as 6-15,46-53,57-64,93-98,109-115,147-155,161-166,199-207 for wild-type OprG and 6-13,46-53,57-63,92-98,109-118,145-155,161-170,199-206 for P92A OprG from the mean of the 20 conformers.

An inspection of the wild-type and P92A OprG structures also shows two girdles of aromatic residues positioned at the rims of the β-barrel with their side chains facing outwards toward the hydrophilic/hydrophobic interface of the lipid bilayer. The girdle on the periplasmic side is very well defined and consists of F6, F53, W57, Y98, F108, Y154, F162, and F207. The girdle on the extracellular side is more incomplete with only F13, Y168, and Y199 contributing. The presence of aromatic residues at the membrane interface is typical for many membrane proteins and particularly well pronounced in β-barrel OMPs. Aromatic side-chains anchor membrane proteins in the membrane and help to define the boundaries of the membrane-embedded portions of membrane proteins (Hong et al., 2007; Schulz, 2002).

Dynamics of wild-type and P92A OprG in DHPC micelles

The overall rotational correlation times of the protein-micelle complexes were determined by one-dimensional 1H-TRACT experiments (Lee et al., 2006). They were 9 and 13 ns for wild-type and P92A OprG, respectively, when measured at 45°C in the 6.5-10.5 ppm regions (Figures S3A and C). For comparison, the overall correlation times of two 8-stranded β-barrels of similar size, OprH and OmpX, were 22 and 21 ns, respectively (Edrington et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2006). The low overall correlation times of both OprGs are probably the result of their relatively long disordered loops that tumble faster than the micelle-embedded barrel portions of both proteins. When only β-barrel peaks are included in the calculation (region 8.9-9.9 ppm), the overall rotational correlation times are 38 and 40 ns, for wild-type and P92A OprG, respectively (Figures S3B and D). The longer correlation times of the P92A mutant compared to the wild-type protein likely reflects the different lengths of β-strands 5, 6 and 7 and loops 3 in the two proteins.

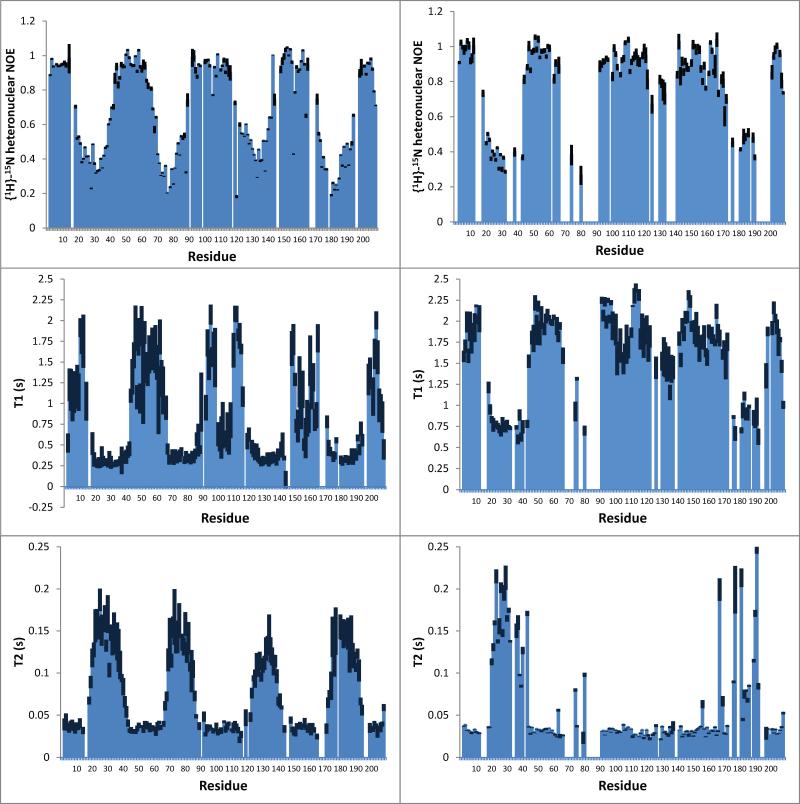

To examine the internal backbone dynamics on the ps to ns time scale, we measured the longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times and the {1H}-15N NOEs of both proteins. As shown in Figure 9 (top panels), the heteronuclear NOEs are largest for the residues in the β-barrel, indicating their restricted motions, and much smaller in the loops and turns, indicating increased flexibilities of these structural elements. Similarly, residues in the well-ordered barrel region have relatively long T1 and short T2 values in comparison with the much more flexible loop residues (Figure 9, middle and bottom panels). The {1H}-15N NOE, T1 and T2 values generally follow the topology of wild-type and mutant OprG, confirming that the barrel portions are well structured and that the loops are largely disordered. Some significant differences between wild-type and P92A OprG are also evident. Loop 3 appears to be quite ordered in P92A, but highly flexible in wild-type OprG. The data show that loop 3 of wild-type undergoes large-scale motions on the ps to ns time scale, while it is rather rigid in P92A OprG. Although Pro92 is at the top of β-strand 4, it influences the flexibility of loop 3 that is attached to β-strands 5 and 6, presumably through a modified hydrogen bonding pattern that surrounds Pro 92 in wild-type, but not in mutant OprG (Figures 6C and D).

Figure 9. Backbone dynamics of OprG.

{1H}-15N heteronuclear NOEs (upper panels), longitudinal relaxation times (middle panels), and transverse relaxation times (lower panels) of OprG (left side) and P92A OprG (right side) in DHPC micelles determined at 800 MHz and 45°C are plotted as a function of the amino acid sequence. Black bars in the T1 and T2 plots are the upper limits of the standard deviations. Black bars in the NOE plots represent the upper limits of the standard errors. See also Figure S3.

Discussion

The function of OprG in the OM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa has remained enigmatic since an early report on its potential physiological role as a low-affinity iron transporter (Yates et al., 1989). Other previous studies suggested possible roles as diverse as a cation channel (McPhee et al., 2009), a transporter of hydrophobic molecules via a lateral gating mechanism (Touw et al., 2010), or a facilitator of the inhibitory action of some antibiotics such as norflaxin, kanamycin, or tetracyclin on the growth of P. aeruginosa (Chamberland et al., 1989; Peng et al., 2005). Like McPhee et al (McPhee et al., 2009), we attempted to determine the electrophysiological activity of reconstituted OprG in black lipid membranes. Despite repeated efforts, we were unable to reproduce the large channel pores seen by these authors, but we did observe small broadly distributed OprG-related currents, which however were independent of any of the Pro mutations or any potential substrates or antibiotics that we added (data not shown). On the other hand, the combination of the liposome-swelling assay and cell growth experiments proved to be excellent for identifying new physiological substrates of OprG-mediated transport through the OM. These approaches indicated for the first time that OprG forms a pore for the permeation of small amino acids through lipid bilayers. Therefore, OmpW family proteins (Figure 1A) appear to have quite diverse functions with some homologs such as OmpW from P. fluorescens contributing to the uptake of polycyclic aromatic compounds (Neher and Lueking, 2009), OprG from P. putida facilitating transport of hydrocarbons through the OM (Walzer et al., 2009), and OprG from P. aeruginosa facilitating the uptake of small amino acids (this work). However, it should be kept in mind that the previous assignments of function in the other Pseudomonas species were not confirmed by protein purification and in vitro transport assays like we have done here for P. aeruginosa OprG.

Our finding that OprG functions as a transporter for small amino acids may not be totally unexpected. Genes involved in a common metabolic pathway are usually organized into operons and even higher order organizations in bacterial genomes (Lathe et al., 2000). Therefore, possible functions of the oprG gene may be guessed by examining functions of neighboring genes. Although the exact functions of genes located next to oprG are presently unknown, BLAST searches of two neighboring gene loci of oprG in P. aeruginosa reveal that these genes may be involved in amino acid and peptide transport through the inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (Figure 1B). This interesting coincidence lends further indirect support that OprG may indeed be a facilitator of amino acid transport across the OM of P. aeruginosa.

How can this protein possibly facilitate the diffusion of small amino acids through the outer membrane? OprG forms a narrow channel, with both polar and apolar side chains facing the inside of the 8-stranded β-barrel. The channel is probably too narrow to accommodate even the smallest amino acid, glycine that we found can be translocated by OprG. Alanine, serine, threonine, and valine would be even more difficult to fit into the small pore of OprG. A strong alternative possibility that has yet to be tested is that OprG may function as an oligomer in membranes and that the relevant amino acids are translocated along a yet to be defined interface between OprG protomers or OprG and the lipid bilayer. Our result that the P92A is unable to facilitate amino acid permeation through lipid bilayers in our liposome-swelling assay indicates that the unusual barrel wall in the region of the interfacial proline cluster likely contributes to the mechanism of amino acid transport by OprG.

The solution structure of wild-type OprG in DHPC micelles exhibits extracellular loops that are much more flexible than in the previously determined crystal structure (Touw et al., 2010). The average length of β-strands in the crystal structure is 15.3 residues, extending well above the polar-apolar interface of the OM, while in solution it is 7.9 for wild-type and 8.6 for P92A OprG, i.e. about 24 to 26 Å, which approximately matches the hydrophobic thickness of the OM lipid bilayer (Wu et al., 2014). Different lengths of well-structured β-barrels are commonly observed when crystal and solution structures of the same OMPs are compared. For example, the β-barrels of OmpA (Cierpicki et al., 2006; Pautsch and Schulz, 2000), OmpG (Liang and Tamm, 2007; Yildiz et al., 2006), and OmpX (Fernandez et al., 2004; Vogt and Schulz, 1999) are longer in crystals than in lipid micelles. The lengths of the β-barrels in the solution structures typically match the hydrophobic lengths of their outer perimeters (~24 Å) (Lomize et al., 2006), whereas those of the crystal structures are often considerably longer with hydrophilic β-barrels extending into hydrophilic regions above the hydrophobic portions. The β-barrel in the NMR structural ensemble of OprG is also more circular in cross-section compared with the more elliptical β-barrel observed in the crystal structure. Apart from the different environments that may be responsible for this difference, it is also possible that the crystallization conditions favor just one of the multiple allowed conformations of the NMR structural ensemble. Regardless, it should be recognized that none of these structures were determined in their natural environments, i.e. in an asymmetric LPS-containing lipid bilayer. Crystal structures are determined in close-packed protein samples in which the extracellular loops often make multiple contacts to neighboring proteins, which could impart additional β-structure on them. Most NMR structures of OMPs, like the ones of OprG here, have been determined in lipid micelles, which are not physiological environments either. However, some were also determined in lipid nanodiscs (Hagn et al., 2013), which provide more natural bilayer-like environments. Even in nanodiscs, the lengths of the β-barrels are still shorter than in the crystals. An interesting intermediate case is the E. coli protein OmpW, which showed concerted hinge motions of partially β-structured loops as measured by solution NMR in 30-Fos micelles (Horst et al., 2014). We have recently made good progress with reconstituting OprG into different kinds of lipid nanodiscs that proved suitable for further NMR studies on this protein in a more bilayer-like and hence more physiological environment (Kucharska et al., 2015). Although the spectra are not yet resolved well enough to allow for a structure determination of OprG in nanodiscs, it is already clear that the loops of OprG are also disordered in this more bilayer-like environment.

Unlike in the crystal structure (Figure S1A), Pro61, Pro91, and Pro92 do not form a lateral gate and are not part of the β-barrel in the solution structures (Figures 7 and 8). However, the barrel-to-loop transitions in the proline-rich region and elsewhere were differently affected by the proline-to-alanine mutation in the mutant compared to the wild-type solution structure. Therefore, and based on our activity measurements with many potential substrates, we consider it unlikely that hydrophobic substrates escape through a lateral gate into the hydrocarbon portion of the bilayer as has been proposed simply based on the crystal structure and in analogy with the fatty acid transporter FadL (Touw et al., 2010). Rather than forming a lateral gate, the prolines contribute to the transitions of the barrel into loop 2 in both the wild-type and P92A structures (Figures 7 and 8). However, the longer strands 4 and 5 in the mutant compared to the wild-type give rise to a highly asymmetric barrel rim in the mutant, but a more even and horizontal barrel rim in the wild-type protein. At the same time, loop 3 is much more ordered in P92A and more dynamic on the ps to ns time-scale in the wild-type protein (Figure 9). Therefore, it seems likely that the symmetric barrel structure, the configuration of the Pro92 in the highly conserved proline cluster region, and/or the flexibility of loop 3 all contribute to the amino acid translocation activity of OprG. For comparison, it is interesting that loop flexibility of the Neisseria β-barrel protein Opa60 was also important for receptor recognition of this protein (Fox et al., 2014). If OprG indeed forms a functional oligomer in the membrane, mutation of Pro92 could very well hamper or prevent oligomerization by direct Pro interaction, changes of the barrel shape, or altered loop dynamics. Alternatively or in addition, the observed dynamics of extracellular loops 2 and 3 may contribute to amino acid translocation by providing chaperoning environments in the membrane. Concerted loop motions have been shown to contribute to the function of another β-barrel OM protein (Zhuang et al., 2013).

Unfortunately the P66A, P91A, and double Pro mutants did not stably insert into lipid bilayers to assess the effects of these potentially interesting mutations on the amino acid translocation activity of OprG. These proteins also gave NMR spectra of much poorer quality, which prevented us from determining changes in their dynamic structures, which might have offered additional clues on the mechanism of amino acid transport by OprG. Despite these limitations, these experiments informed us that the proline cluster region is critically important for obtaining stable and functional proteins in micelles and lipid bilayers. It will therefore be interesting to further examine the critical role that this region plays in the mechanism of small amino acid transport across the OM of P. aeruginosa.

In conclusion, the results of this work provide a structural and dynamic framework to formulate new hypotheses on how OprG-facilitated amino acid transport across the outer membrane might work. It will be interesting to test and distinguish between such hypotheses in future work and it will be particularly interesting to see if any of the proposed mechanisms might affect the antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its cytotoxic effects on epithelial cells in the lungs of infected patients.

Experimental Procedures

Expression and Purification of OprG in Escherichia coli

The P. aeruginosa strain PA01 OprG expression construct was designed without the N-terminal signal sequence, i.e. residues 1 to 26 were replaced with Met1 so that His27 becomes His2 in our numbering system. Wild-type and mutant proteins were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) cells and purified and refolded from inclusion bodies in the present of detergent as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Liposome swelling assay

The assay was performed as described previously (Nikaido and Rosenberg, 1983) with the following modifications. Liposomes were made by suspending a dried film of 3 μmoles egg phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Al) and 0.15 μmoles egg L-α-phosphatidic acid (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Al) in 20 μL of a 1.875 mM micellar solution of n-dodecylphosphocholine (Anatrace, Maumee, OH) in water containing 2 (protein-to-lipid ratio 1:1575) or 6 (protein-to-lipid ratio 1:525) nmoles OprG, sonicated for 15 min, and completely dehydrated in vacuo. After rehydration in assay buffer (12 mM stachyose, 10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5) under vigorous shaking and 2 times 15 min sonication, a suspension of multilamellar vesicles containing OprG in their membranes was obtained. Reconstitution of OprG was quantitative as far as detectable on Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gels (data now shown).

In a 96 well plate (Corning #3631), 5 μL OprG liposomes were diluted with 200 μL of an equiosmolar analyte solution in 10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, and absorbance was monitored at 405 nm using a Perkin-Elmer HTS 7000 plate reader over a period of 5 min. Data was analyzed following published procedures (Bangham et al., 1967; Nikaido and Rosenberg, 1983) and swelling rates were reported relative to L-alanine.

Growth assays

The wild-type PA01 (H899) and oprG-deficient H900 strains of P. aeruginosa (McPhee et al., 2009) were kind gifts from Dr. Robert Hancock (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada). Growth assays with wild-type PA01 and mutant H900 strains were performed following a described protocol (Tamber et al., 2006) with some small changes. The bacteria were grown overnight in BM2 media supplemented with several desired nitrogen sources as indicated in Results. The overnight cultures were sub-cultured to a starting optical density of 0.01 at 600 nm in pre-warmed fresh BM2 media containing the specific nitrogen sources. These cultures were grown at 37°C in an orbital shaker shaking at 250 rpm. To ensure sufficient aeration, 50 ml cultures were grown in 1-L flasks. Aliquots of the cultures were taken at specified time intervals and the turbidity at 600 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer.

NMR Spectroscopy

All NMR experiments were recorded at 45 °C on a Bruker Avance III 800 spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryoprobe. All double- and triple-resonance experiments were performed using the Bruker Topspin version 2.1.6 software suite. Sequential backbone assignments were obtained by recording TROSY versions of HNCA, HNCB, HNCO and HNCACO experiments. 15N-edited 15N-1H-1H NOESY-TROSY and 15N-1H-15N HSQC-NOESY-HSQC experiments with mixing times of 200 ms were recorded to obtain nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs). T1, T2, and {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOEs were measured using two-dimensional 15N-1H TROSY-based experiments. NMR data were processed with NMRPipe and analyzed with Sparky software (Goddard and Kneller).

H/D Exchange Experiments

15N-labeled NMR samples of refolded wild-type and P92A OprG were dried overnight by lyophilization. D2O was added to ~1 mM protein, the samples were mixed by vortexing, and 15N-TROSY spectra were collected after 20 min, 1 hour, 4 hours, 1 day and 1 week after D2O addition. Hydrogen bonds were identified by the presence of corresponding resonances in the 15N-TROSY spectra.

Structure Calculation

Distance constraints were calibrated and calculated manually based upon an average distance of 3.3 Å between β-strands. Backbone dihedral angle constraints were determined from chemical shifts corrected for deuterium and TROSY effects using TALOS+ (Shen et al., 2009). Hydrogen bond constraints derived from H/D exchange experiments were set at 2.5 and 3.5 Å for HN-O and N-O distances, respectively. Structure calculations were performed using CNS version 1.2 (Brunger et al., 1998) using 4,000 high temperature, 8,000 torsion slow-cool, and 8,000 Cartesian slow-cool annealing steps. A total of 100 structures were calculated, and the 20 lowest energy structures were selected for ensemble analysis. Ramachandran map analysis was performed with PROCHECK-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996).

Data Deposition

NMR chemical shifts and other data have been deposited in the Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance Data Bank and the structural coordinates of wild-type and P92A OprG have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 2NGL and 2N6P, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

P. aeruginosa OprG is a porin for small amino acid and related compound transport

Solution NMR structures of OprG and a Pro mutant do not show a lateral Pro gate

Extracellular loops are disordered to different levels in wt and mutant OprG

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 GM051329. We thank Dr. R. Hancock for PA strains H899 and H900 and Drs. Mollie Hughes, Brad Bennett, and Tiandi Zhuang for numerous helpful discussions. We also thank Dr. Luiz Salay (Ilhéus, Brazil), Dr. Min Chen (Amherst, MA), and Dr. Mahendran Radhakrishnan (Oxford, UK) for their great efforts to characterize the electrophysiological behavior of OprG.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: All authors designed experiments, IK performed most experiments, PS performed the liposome swelling assays, TE performed the initial NMR experiments, BL helped with all NMR experiments, all authors evaluated data, IK and LKT wrote the paper.

References

- Bangham AD, De Gier J, Greville GD. Osmotic properties and water permeability of phospholipid liquid crystals. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 1. 1967;5:225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland S, Bayer AS, Schollaardt T, Wong SA, Bryan LE. Characterization of mechanisms of quinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated in vitro and in vivo during experimental endocarditis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1989;33:624–634. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.5.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cierpicki T, Liang B, Tamm LK, Bushweller JH. Increasing the accuracy of solution NMR structures of membrane proteins by application of residual dipolar couplings. High-resolution structure of outer membrane protein A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:6947–6951. doi: 10.1021/ja0608343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcour AH. Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1794:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denome SA, Stanley DC, Olson ES, Young KD. Metabolism of dibenzothiophene and naphthalene in Pseudomonas strains: complete DNA sequence of an upper naphthalene catabolic pathway. Journal of bacteriology. 1993;175:6890–6901. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6890-6901.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrington TC, Kintz E, Goldberg JB, Tamm LK. Structural basis for the interaction of lipopolysaccharide with outer membrane protein H (OprH) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:39211–39223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, Hilty C, Wider G, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. NMR structure of the integral membrane protein OmpX. Journal of molecular biology. 2004;336:1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DA, Larsson P, Lo RH, Kroncke BM, Kasson PM, Columbus L. Structure of the Neisserial outer membrane protein Opa(6)(0): loop flexibility essential to receptor recognition and bacterial engulfment. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2014;136:9938–9946. doi: 10.1021/ja503093y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. University of California; San Francisco: [Google Scholar]

- Govan JR, Brown AR, Jones AM. Evolving epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the Burkholderia cepacia complex in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Future Microbiol. 2007;2:153–164. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagn F, Etzkorn M, Raschle T, Wagner G. Optimized phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs facilitate high-resolution structure determination of membrane proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:1919–1925. doi: 10.1021/ja310901f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock RE, Brinkman FS. Function of pseudomonas porins in uptake and efflux. Annual review of microbiology. 2002;56:17–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn EM, Patel DR, Lepore BW, Indic M, van den Berg B. Transmembrane passage of hydrophobic compounds through a protein channel wall. Nature. 2009;458:367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature07678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, Park S, Jimenez RH, Rinehart D, Tamm LK. Role of aromatic side chains in the folding and thermodynamic stability of integral membrane proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:8320–8327. doi: 10.1021/ja068849o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, Patel DR, Tamm LK, van den Berg B. The outer membrane protein OmpW forms an eight-stranded beta-barrel with a hydrophobic channel. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:7568–7577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst R, Stanczak P, Wuthrich K. NMR polypeptide backbone conformation of the E. coli outer membrane protein W. Structure. 2014;22:1204–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DA, Tetu SG, Phillippy K, Chen J, Ren Q, Paulsen IT. High-throughput phenotypic characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa membrane transport genes. PLoS genetics. 2008;4:e1000211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska I, Edrington TC, Liang B, Tamm LK. Optimizing nanodiscs and bicelles for solution NMR studies of two beta-barrel membrane proteins. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2015;61:261–274. doi: 10.1007/s10858-015-9905-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathe WC, 3rd, Snel B, Bork P. Gene context conservation of a higher order than operons. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2000;25:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Hilty C, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Effective rotational correlation times of proteins from NMR relaxation interference. Journal of magnetic resonance. 2006;178:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Tamm LK. Structure of outer membrane protein G by solution NMR spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:16140–16145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705466104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomize AL, Pogozheva ID, Lomize MA, Mosberg HI. Positioning of proteins in membranes: a computational approach. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society. 2006;15:1318–1333. doi: 10.1110/ps.062126106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JB, Tamber S, Bains M, Maier E, Gellatly S, Lo A, Benz R, Hancock RE. The major outer membrane protein OprG of Pseudomonas aeruginosa contributes to cytotoxicity and forms an anaerobically regulated, cation-selective channel. FEMS microbiology letters. 2009;296:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesaros N, Nordmann P, Plesiat P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Van Eldere J, Glupczynski Y, Van Laethem Y, Jacobs F, Lebecque P, Malfroot A, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance and therapeutic options at the turn of the new millennium. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:560–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler WJ, Constantine KL, Friedrichs MS, Bell AJ, Ernst EG, Lavoie TB, Mueller L. Characterization of the three-dimensional solution structure of human profilin: 1H, 13C, and 15N NMR assignments and global folding pattern. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13818–13829. doi: 10.1021/bi00213a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi B, Nandy RK, Sarkar A, Ghose AC. Structural features, properties and regulation of the outer-membrane protein W (OmpW) of Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology. 2005;151:2975–2986. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27995-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher TM, Lueking DR. Pseudomonas fluorescens ompW: plasmid localization and requirement for naphthalene uptake. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:553–563. doi: 10.1139/w09-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H, Rosenberg EY. Porin channels in Escherichia coli: studies with liposomes reconstituted from purified proteins. Journal of bacteriology. 1983;153:241–252. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.241-252.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautsch A, Schulz GE. High-resolution structure of the OmpA membrane domain. Journal of molecular biology. 2000;298:273–282. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Xu C, Ren H, Lin X, Wu L, Wang S. Proteomic analysis of the sarcosine-insoluble outer membrane fraction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa responding to ampicilin, kanamycin, and tetracycline resistance. Journal of proteome research. 2005;4:2257–2265. doi: 10.1021/pr050159g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan S, Saiman L. Pulmonary infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Semin Respir Infect. 2002;17:47–56. doi: 10.1053/srin.2002.31690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz GE. The structure of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2002;1565:308–317. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamber S, Ochs MM, Hancock RE. Role of the novel OprD family of porins in nutrient uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of bacteriology. 2006;188:45–54. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.45-54.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touw DS, Patel DR, van den Berg B. The crystal structure of OprG from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a potential channel for transport of hydrophobic molecules across the outer membrane. PloS one. 2010;5:e15016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg B. The FadL family: unusual transporters for unusual substrates. Current opinion in structural biology. 2005;15:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt J, Schulz GE. The structure of the outer membrane protein OmpX from Escherichia coli reveals possible mechanisms of virulence. Structure. 1999;7:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walzer G, Rosenberg E, Ron EZ. Identification of outer membrane proteins with emulsifying activity by prediction of beta-barrel regions. Journal of microbiological methods. 2009;76:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu EL, Fleming PJ, Yeom MS, Widmalm G, Klauda JB, Fleming KG, Im W. E. coli outer membrane and interactions with OmpLA. Biophysical journal. 2014;106:2493–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Lin X, Wang F, Ye D, Xiao X, Wang S, Peng X. OmpW and OmpV are required for NaCl regulation in Photobacterium damsela. Journal of proteome research. 2006;5:2250–2257. doi: 10.1021/pr060046c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JM, Morris G, Brown MR. Effect of iron concentration and growth rate on the expression of protein G in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS microbiology letters. 1989;49:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz O, Vinothkumar KR, Goswami P, Kuhlbrandt W. Structure of the monomeric outer-membrane porin OmpG in the open and closed conformation. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:3702–3713. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang T, Chisholm C, Chen M, Tamm LK. NMR-based conformational ensembles explain pH-gated opening and closing of OmpG channel. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:15101–15113. doi: 10.1021/ja408206e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.