Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the remaining life expectancy with and without polypharmacy for Swedish women and men aged 65 years and older.

Design

Age-specific prevalence of polypharmacy from the nationwide Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (SPDR) combined with life tables from Statistics Sweden was used to calculate the survival function and remaining life expectancy with and without polypharmacy according to the Sullivan method.

Setting

Nationwide register-based study.

Participants

A total of 1,347,564 individuals aged 65 years and older who had been prescribed and dispensed a drug from July 1 to September 30, 2008.

Measurements

Polypharmacy was defined as the concurrent use of 5 or more drugs.

Results

At age 65 years, approximately 8 years of the 20 remaining years of life (41%) can be expected to be lived with polypharmacy. More than half of the remaining life expectancy will be spent with polypharmacy after the age of 75 years. Women had a longer life expectancy, but also lived more years with polypharmacy than men.

Discussion

Older women and men spend a considerable proportion of their lives with polypharmacy.

Conclusion

Given the negative health outcomes associated with polypharmacy, efforts should be made to reduce the number of years older adults spend with polypharmacy to minimize the risk of unwanted consequences.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, aged, life expectancy, sex difference, drug use

Polypharmacy is common among older adults and has been linked to an increased risk of drug-drug interactions, inappropriate prescribing, adverse drug reactions, lower adherence to drug regimens, hospitalization, and even mortality.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Polypharmacy can be defined as the concurrent use of multiple medications1 (often with the cutoff of 5 or more drugs; a cutpoint that has been shown to have good discriminative properties6). The prevalence of polypharmacy is often found to increase with age.7 This can be problematic given that the altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in old age, together with increasing number of comorbidities, make older people more sensitive to the effects of drugs.8

Older adults have been found to use an increasing number of drugs as they age,7 and longitudinal studies show an increasing proportion of persons with polypharmacy over time.9 Earlier studies have highlighted the importance of considering life expectancy in relation to prescribing, especially for patients with limited life expectancy.5, 10 In persons with limited life expectancy, the time needed to have the potential benefits of a treatment will in some cases be longer than their expected remaining life. However, little is known about how long time older adults spend with polypharmacy.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the estimated time older people are exposed to polypharmacy. By combining information on length of life and information on polypharmacy by age and sex, we can estimate the time spent with polypharmacy in older women and men in Sweden in relation to life expectancy. Thus, the aim of the study was to investigate the proportion of remaining life, and number of years, spent with polypharmacy after age 65 years among Swedish women and men.

Methods

Data Source

The Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (SPDR) was used to measure the prevalence of polypharmacy in the Swedish population aged 65 years and older. The SPDR contains individual-level information on all drugs prescribed and filled at pharmacies by Swedish citizens (including prescribed vitamins, minerals, dermatological and eye preparations, and as-needed used drugs), but not over-the-counter drugs and drugs used in hospitals.11

Sample

Among persons aged 80 years and older, approximately 90% of the total population is covered by the SPDR,12 the coverage in the younger age groups was lower, approximately 80%. Persons that were not covered by the SPDR have not dispensed a drug during the study period. For each individual alive at the end of the study period, we had information on all prescription drugs dispensed from July 1 to September 30, 2008 (n = 1,347,564).

Drug Use and Polypharmacy

The dispensed drugs were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic and Chemical (ATC) classification system. If a person was prescribed 2 drugs with the same ATC code (5th level, chemical substance) during the study period, it was counted as one dispensing. By combining the information on date of dispensing, the amount of drug and dosage, we could calculate the number of drugs that should be used on September 30, 2008 (for a more detailed description of the calculations, see Wastesson et al12). Polypharmacy was defined as the concurrent use of 5 or more drugs, calculated as a 1-day-point prevalence, for September 30, 2008.

Statistical Analysis

The Sullivan method13 is usually used for dividing life expectancy into disabled and disability-free years of life. We propose a novel use of the Sullivan method to calculate the survival function and the remaining years of life spent with and without polypharmacy at different ages. Information on period life tables for 2008 were available from Statistics Sweden.14 Mortality data were available by single age groups for ages 65 to 99 years, and with an open-ended age interval for centenarians (100+ years). The calculations were done for the total population aged 65 years and older, and given the gender differences in drug use,15 for women and men separately. A more detailed description on the calculations used in the Sullivan method can be found elsewhere.16 The study was approved by the ethical board in Stockholm (Dnr 2009/477–31/3).

Results

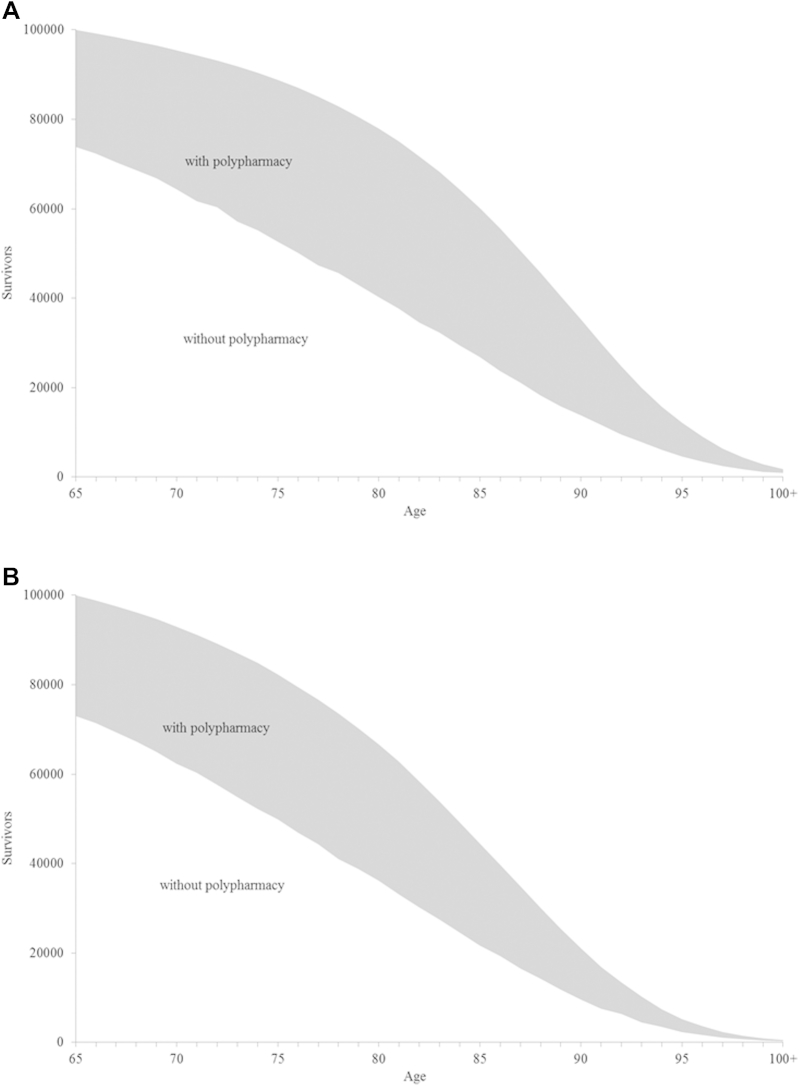

A total of 1,347,564 individuals (775,109 women; 572,455 men) aged 65 years or older had a record in the SPDR. The use of drugs ranged from 0 to 40 drugs concomitantly, with a median of 4 drugs (interquartile range 2–6). The survival function for Swedish women and men, partitioned into survivors with and without polypharmacy (≥5 drugs) are depicted in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Survival function separated by polypharmacy (with and without), Swedish female (A) and male (B) population 2008.

The overall survival for female and male Swedes after age 65 years is represented by the outer contour line in Figure 1 (A and B). The higher longevity of women as opposed to men can be perceived in women's more rectangular survival function; with half of the women surviving to the age of 87 years compared with 84 years for men. The shaded area under the curve separates the number of survivors into those with and without polypharmacy at each age. Women have a larger shaded area, indicating a larger proportion of women with polypharmacy at each age.

The frequency of polypharmacy increased with age, from 27% at age 65 years to approximately 60% among nonagenarians (Table 1). However, in the centenarian group (100+), the frequency of polypharmacy was lower (52%) than among nonagenarians (59%). Women and men had a similar frequency of polypharmacy until age 80 years, but women had a higher prevalence of polypharmacy between ages 80 and 99 years. The gender difference declined in the centenarian group.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Polypharmacy (PP) and Life Expectancy (LE) for Selected Ages Above 65 Total LE and divided into years with and without polypharmacy of the total remaining LE. Swedish total, female and male population 2008.

| Age | Total Population |

Female Population |

Male Population |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypharmacy, % | LE, y |

Polypharmacy, % | LE, y |

Polypharmacy, % | LE, y |

|||||||

| Total | Without PP | With PP | Total | Without PP | With PP | Total | Without PP | With PP | ||||

| 65 | 26.6 | 19.7 | 11.6 | 8.1 | 26.2 | 21.0 | 12.1 | 8.9 | 27.0 | 18.1 | 11.0 | 7.1 |

| 70 | 32.8 | 15.7 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 32.6 | 16.9 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 33.0 | 14.3 | 8.1 | 6.2 |

| 75 | 40.1 | 12.0 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 40.8 | 13.0 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 39.4 | 10.8 | 5.8 | 5.1 |

| 80 | 47.3 | 8.7 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 48.4 | 9.4 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 45.8 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| 85 | 53.9 | 6.0 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 55.4 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 51.3 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| 90 | 58.9 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 60.9 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 54.6 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| 95 | 60.7 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 62.2 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 55.9 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| 100+ | 52.4 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 48.1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 48.1 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

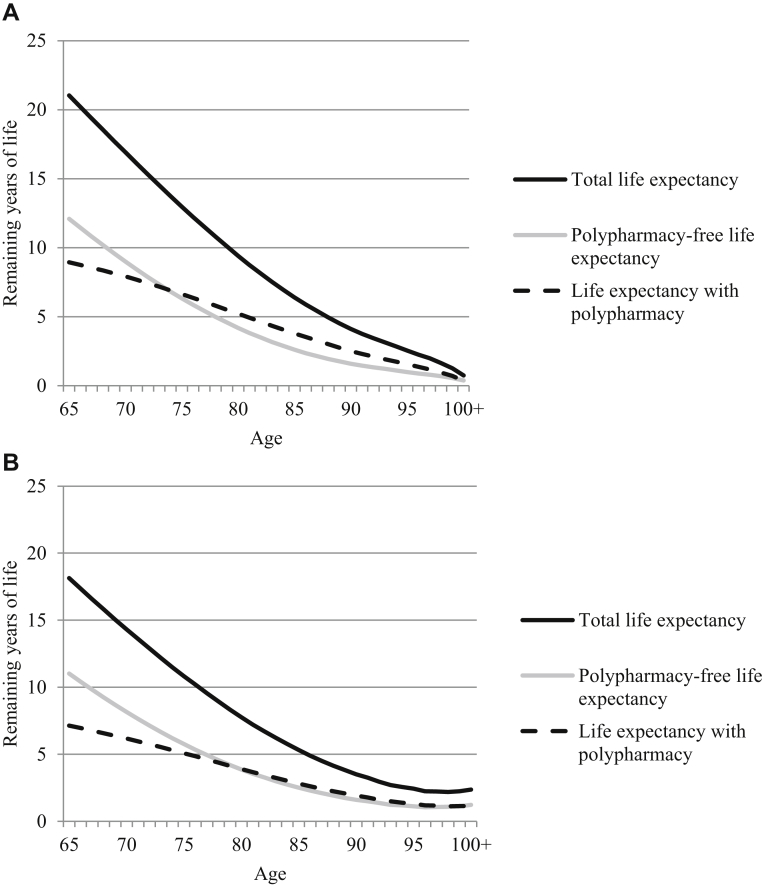

In Table 1, the polypharmacy-free life expectancies for the total population and for women and men are shown. In the total study population, the remaining years of life were 20 at age 65 years, 10 years at age 78, and 5 years at age 87. At age 65 years, approximately 8 of the 20 remaining years of life could be expected to be lived with polypharmacy (41.2%). After the age of 75 years, more than half of the remaining life expectancy was spent with polypharmacy.

Women had a longer life expectancy than men until advanced ages. Women also tended to live more years, and have a larger share of life with polypharmacy, than men. Women could expect to spend 50% or more of their remaining life with polypharmacy after age 73 years, whereas men could expect to spend 50% or more with polypharmacy at age 79 years (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Life expectancy, total, with and without polypharmacy. Swedish female (A) and male (B) population, 2008.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate polypharmacy-free life expectancy. A 65-year-old in Sweden can expect to live 20 more years. Of these, 8 years will be spent with polypharmacy. Women have a longer life expectancy than men, but can expect to live half of the remaining life with polypharmacy after the age of 73 years compared with 79 years for men. Thus, women live more years, and a larger share of their remaining life, with polypharmacy than men. Polypharmacy is not necessarily inappropriate, but given the risk of drug-drug interactions, inappropriate prescribing, adverse drug reactions, lower adherence to drug regimens, hospitalization, and mortality,1, 2 it should be avoided if possible. Our results suggest that a large proportion of older adults will spend many years exposed to polypharmacy. Based on our calculations, more than two-fifths of the remaining life was expected to be lived with polypharmacy for Swedes aged 65 years in 2008 if they were to follow the regimen of medication and mortality observed in 2008.

The use of drugs in general, as well as the use of multiple medications, is increasing year-by-year in the older population.7, 17, 18 Older adults with comorbidities are rarely included in drug trials.19, 20 Thus, the use of drugs among older adults can to a large extent be considered experimental. The increased use of drugs is partly driven by the use of single disease guidelines,21 and it has been suggested that drug treatment in complex older adults should focus more on the deliberate avoidance of polypharmacy.10 Conceptual frameworks have been developed to include deprescribing in the prescribing process.22 In fact, there is emerging evidence that deprescribing can have positive health effects for older adults with complex health problems.23, 24 Thus, our finding that older adults spend extensive periods with polypharmacy should be a case of concern.

Especially among older adults with a very limited life expectancy, where the time needed before a treatment will have a potentially beneficial effect can be longer than their remaining life expectancy, deprescribing could be warranted.5, 10 However, we find that people can expect to spend more than half of their remaining life expectancy exposed to polypharmacy all the way up to 100 years of age. Given that a centenarian on average can expect to live only 1 more year, their limited life expectancy should be taken into account when clinical decisions are made. In line with this, we found that centenarians actually had a lower prevalence of polypharmacy than nonagenarians.

The prevalence of polypharmacy in our study increased from approximately 30% at age 65 years, to approximately 65% at age 95 years. The prevalence of polypharmacy has been found to range between 27% and 59% in a systematic review of nonhospitalized older adults living at home,25 and between 38% and 91%, in a review of older adults in long-term care facilities.26 Our results are in line with the range presented in the reviews, given that we both include home-dwelling and persons living in long-term care facilities. Ideally, our results should have been presented for persons living at home and long-term care facilities separately. But data on life expectancy in long-term care facilities are not available in Sweden.

Women have a longer life expectancy, but also experience more health problems than men; the so called male-female health paradox.27, 28, 29, 30 We found that women have longer life expectancy, and spend a larger proportion and more years, with polypharmacy. Thus, women spend more time exposed to the risks of polypharmacy both in absolute years and as a proportion of their life. The similarity in results between drug use and health are expected because drug use is considered as a valid proximate measure of health status.31, 32 Hence, polypharmacy-free life expectancy could potentially be used to study health differentials between groups.

The present study has some limitations. By using the Sullivan method, we assume that people with polypharmacy (based on our 1-day-point prevalence) stay on polypharmacy. The validity of this assumption should ideally be studied within a longitudinal framework. In general, polypharmacy increases with age7, 9; thus, people transitioning out of polypharmacy should not pose a major limitation to this study. However, it might be problematic in the centenarian group where the prevalence of polypharmacy was lower than in the younger age groups. The low use of drugs among centenarians12, 33, 34 could reflect a transition out of polypharmacy as an end-of-life approach when discontinuation of drug therapy is warranted.33 Further, we do not have information about over-the-counter drugs, which leads to an underestimation of the total consumption of drugs. A more general limitation with the Sullivan method is that it assumes the same mortality pattern in both the group with and without polypharmacy. Because drug use also can be used as a health measure, the group with polypharmacy will probably have higher mortality. The strengths of this study are the complete drug use data available from Swedish registers, and the method used for calculating the 1-day-point prevalence of drug use. The 1-day-point prevalence is conservative compared with other studies that have summarized drug use from a longer time period. If the persons are adherent to their drug regimens, all the prescribed drugs should have been consumed concomitantly on the day of the study.

Conclusion

This study highlights the extensive proportion of their remaining lives older adults spend exposed to polypharmacy. On average, a 65-year-old Swede will spend 8 years of his or her remaining 20 years of life with polypharmacy. Given the negative health outcomes associated with polypharmacy, efforts should be made to reduce the number of years older adults spend with polypharmacy to minimize the risk of unwanted consequences. The remaining life expectancy of the patient should be taken into consideration when managing the drug treatment of older patients.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant 2012–1503) and the European Research Council (grant 240795). The financial sponsors played no part in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing of the study.

References

- 1.Hajjar E.R., Cafiero A.C., Hanlon J.T. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher R.L., Hanlon J., Hajjar E.R. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57–65. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sergi G., De Rui M., Sarti S. Polypharmacy in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:509–518. doi: 10.2165/11592010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried T.R., O'Leary J., Towle V. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2261–2272. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onder G., Liperoti R., Foebel A. Polypharmacy and mortality among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment: Results from the SHELTER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:450.e7–450.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnjidic D., Hilmer S.N., Blyth F.M. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hovstadius B., Hovstadius K., Åstrand B. Increasing polypharmacy—an individual-based study of the Swedish population 2005–2008. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2010;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turnheim K. When drug therapy gets old: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:843–854. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veehof L., Stewart R., Haaijer-Ruskamp F. The development of polypharmacy. A longitudinal study. Fam Pract. 2000;17:261–267. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Mahony D., O'Connor M.N. Pharmacotherapy at the end-of-life. Age Ageing. 2011;40:419–422. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wettermark B., Hammar N., Michael Fored C. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:726–735. doi: 10.1002/pds.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wastesson J.W., Parker M.G., Fastbom J. Drug use in centenarians compared with nonagenarians and octogenarians in Sweden: A nationwide register-based study. Age Ageing. 2012;41:218–224. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan D.F. A single index of mortality and morbidity. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:347–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Sweden. Population statistics. Available at: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/. Accessed December 3, 2014.

- 15.Johnell K., Weitoft G., Fastbom J. Sex differences in inappropriate drug use: A register-based study of over 600,000 older people. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1233–1238. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagger C. Nihon University; Tokyo, Japan: 1999. Health expectancy calculation by the Sullivan Method: A practical guide. Nihon University Population Research Institute Research Paper Series No 68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melzer D., Tavakoly B., Winder R.E. Much more medicine for the oldest old: Trends in UK electronic clinical records. Age Ageing. 2015;44:46–53. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlesworth C.J., Smit E., Lee D.S. Polypharmacy among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States: 1988–2010. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:989–995. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherubini A., Signore S.D., Ouslander J. Fighting against age discrimination in clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1791–1796. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinetti M.E. The gap between clinical trials and the real world: Extrapolating treatment effects from younger to older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:397–398. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gnjidic D., Le Couteur D.G., Hilmer S.N. Discontinuing drug treatments. BMJ. 2014;349:g7013. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bain K.T., Holmes H.M., Beers M.H. Discontinuing medications: A novel approach for revising the prescribing stage of the medication-use process. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1946–1952. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garfinkel D., Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: Addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1648–1654. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Cammen T.J., Rajkumar C., Onder G. Drug cessation in complex older adults: Time for action. Age Ageing. 2014;43:20–25. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elmståhl S., Linder H. Polypharmacy and inappropriate drug use among older people: A systematic review. Healthy Aging Clin Care Elder. 2013;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jokanovic N., Tan E.C., Dooley M.J. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:535.e1–535.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oksuzyan A., Juel K., Vaupel J.W. Men: Good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:91–102. doi: 10.1007/bf03324754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero-Ortuno R., Fouweather T., Jagger C. Cross-national disparities in sex differences in life expectancy with and without frailty. Age Ageing. 2014;43:222–228. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Oyen H., Nusselder W., Jagger C. Gender differences in healthy life years within the EU: An exploration of the “health–survival” paradox. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:143–155. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0361-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jagger C., Weston C., Cambois E. Inequalities in health expectancies at older ages in the European Union: Findings from the Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:1030–1035. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.117705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneeweiss S., Seeger J.D., Maclure M. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:854–864. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madsen M., Andersen P.K., Gerster M. Are familial factors underlying the association between socioeconomic position and prescription medicine? A register-based study on Danish twins. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003292. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi S., Mörike K., Klotz U. The clinical implications of ageing for rational drug therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:183–199. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simiand-Erdociain E., Lapeyre-Mestre M., Bagheri-Charabiani H. Drug consumption in a very elderly community-dwelling population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:691–692. doi: 10.1007/s002280100344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]