Abstract

Bullying perpetration and sexual harassment perpetration among adolescents are major public health issues. However, few studies have addressed the empirical link between being a perpetrator of bullying and subsequent sexual harassment perpetration among early adolescents in the literature. Homophobic teasing has been shown to be common among middle school youth and was tested as a moderator of the link between bullying and sexual harassment perpetration in this 2-year longitudinal study. More specifically, the present study tests the Bully–Sexual Violence Pathway theory, which posits that adolescent bullies who also participate in homophobic name-calling toward peers are more likely to perpetrate sexual harassment over time. Findings from logistical regression analyses (n = 979, 5th–7th graders) reveal an association between bullying in early middle school and sexual harassment in later middle school, and results support the Bully–Sexual Violence Pathway model, with homophobic teasing as a moderator, for boys only. Results suggest that to prevent bully perpetration and its later association with sexual harassment perpetration, prevention programs should address the use of homophobic epithets.

Keywords: bullying, sexual harassment, adolescents

Introduction

Two separate literatures on youth bullying and sexual violence have established that both these forms of violence are widespread public health issues with negative consequences for victims (Basile, 2005; Basile et al., 2006; Black et al., 2011; Espelage, 2012; Espelage, Low, & De La Rue, 2012; Gruber & Fineran, 2008; Nansel, Overpeck, et al., 2001; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Both bullying and sexual violence start in later childhood (Borowsky, Hogan, & Ireland, 1997; Espelage, 2012) and share some conceptual and empirical developmental correlates, but also have unique predictors (Basile, Espelage, Rivers, McMahon, & Simon, 2009; DeSouza & Ribeiro, 2005; Pepler et al., 2006; Pellegrini, 2001). However, very few studies have examined the association between bullying and sexual violence perpetration across adolescence. Given the recognition that bullying perpetration has been linked to the use of homophobic epithets during early adolescence (Basile et al., 2009; Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012; Poteat & Espelage, 2005), this study directly examines the moderating role of homophobic name-calling between bullying and sexual harassment perpetration (one form of sexual violence), among a middle school sample using a longitudinal design.

This study specifically tests the Bully–Sexual Violence Pathway theory proposed by Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger (2012), in which bully perpetration and homophobic teasing perpetration were direct predictors of perpetration of sexual harassment over a 6-month period among middle school youth. This study extends this work using the same sample to evaluate bullying perpetration as having an indirect association to later sexual harassment perpetration through the moderating effect of homophobic name-calling across a 2-year period. More specifically, a moderating effect of homophobic teasing implies that the association between bullying and sexual harassment perpetration would be stronger for higher levels of homophobic teasing perpetration.

Definitions of Bullying, Sexual Harassment, and Homophobic Teasing

For the purpose of this article, bullying perpetration includes verbal and social aggression directed at other students repeatedly over the last month (Espelage & Holt, 2001). Sexual harassment perpetration is defined as directing unwanted sexual commentary, sexual rumor spreading, and touching (e.g., groping or fondling) toward other peers (Basile & Saltzman, 2002; Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012). Homophobic teasing or name-calling perpetration is a particular form of gender-based name-calling (e.g., calling others “gay,” “fag”) that friends and non-friends engage in (Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012). Given these three constructs are all measuring verbal aggression, there is likely to be some overlap, but they have emerged as distinct constructs in previous studies (e.g., low to moderate correlations; Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012; Poteat & Espelage, 2005, 2007). For example, in a review of sexual violence and bullying, Basile et al. (2009) found that sexual violence had some correlates that had not been previously related to bullying, such as use of pornography (Jensen, 1995; Malamuth, Addison, & Koss, 2000) and deviant sexual arousal (Hall & Barongan, 1997; Malamuth, 1986). Thus, we examine the association among bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment separately.

Magnitude of Bullying, Sexual Harassment, and Homophobic Teasing

A recent U.S. nationally representative study found that approximately 28% of 12- to 18-year-old students reported they had been bullied at school during the school year, and victimization was highest among sixth graders (37%), compared with seventh or eighth graders (30% and 31% respectively; Robers, Kemp, & Truman, 2013). Also, approximately 9% to 11% of youth report being called hate-related words having to do with their race, religion, ethnic background, and/or sexual orientation (Robers et al., 2013).

Surveys conducted by the American Association of University Women (AAUW; AAUW Educational Foundation, 2001) reveal that sexual harassment is widespread among youth. Of the students surveyed, about half (48%) of the students in Grades 7 to 12 experienced some form of sexual harassment at school, including unwelcome sexual comments, jokes, and gestures (33%); being shown sexual pictures they did not want to see (13%); being touched in an unwelcome sexual way (8%); or being physically intimidated in a sexual way (6%; AAUW, 2001). While girls are more often the victims of sexual harassment, boys also experience this type of victimization (56% vs. 40%, respectively). Despite the prevalence of sexual harassment in schools, the etiology of sexually harassing behaviors among early adolescence is not well understood.

Homophobic teasing or name-calling is a commonly reported experience, particularly by students who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. Rivers (2001) reported that gay and lesbian students frequently experienced incidents of name-calling (82%) and being teased (58%), and had incidents of assaults (60%). These students also experienced rumor spreading (59%) and social isolation (27%). But homophobic teasing is not only directed at sexual minority students. In California, a large-scale survey of students in Grades 7 to 11 found that 7.5% reported being bullied at school because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation, with two thirds of those students who identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender reporting victimization (California Safe Schools Coalition & 4-H Center for Youth Development, University of California, Davis, 2004). Further, Poteat and Rivers (2010) found among a sample of 253 high school students the use of homophobic epithets was significantly associated with the primary bully role and the supportive roles of reinforcing and assisting the bully for boys and girls. Remaining uninvolved was associated with less use of homophobic language only for girls.

Linking Bullying and Homophobic Teasing With Sexual Harassment Perpetration Through a Gendered Lens

Bullying is in many ways a gendered phenomenon, which could explain why bullying perpetration might be associated with later sexual harassment perpetration. Bullying perpetration can be a means of gaining status among same- and other-sex peers (Faris & Felmlee, 2011; Hanish, Sallquist, DiDonato, Fabes, & Martin, 2012; Rodkin & Berger, 2008). Also, at least for heterosexuals, cross-gender bullying can be an attempt to express interest in a peer as a dating partner (Pellegrini et al., 2010); indeed bullying involvement has been linked to later teen dating violence perpetration (Espelage, Low, Anderson, & De La Rue, 2014; Holt & Espelage, 2005; Miller et al., 2013). When bullying involves homophobic slurs, this serves to marginalize sexual minority youth (Birkett & Espelage, 2014; Espelage, Aragon, Birkett, & Koenig, 2008; Robinson & Espelage, 2011; Robinson, Espelage, & Rivers, 2013) and serves to promote heterosexual masculinity (Herek, 2000). Heterosexual masculinity is the norm in most middle schools, and youth behave in ways to affirm their heterosexuality publicly, and this can include sexual harassment perpetration. This is what we believe underlies the Bully–Sexual Violence pathway; sexual harassment perpetration is a way to combat against perceptions of gender non-conformity (Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012).

Often times, scholars want to equate these three constructs, but it is important to view bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual harassment as aggressive behaviors that are motivated by different factors. Sexual harassment is about gender and power, and is more directly related to hegemonic masculinity and the structural and culturally sanctioned gender role expectations (masculine–feminine) provided to young people (Gruber & Fineran, 2008). In contrast, bullying behaviors include aggression that is done repeatedly but does not always include a gendered component, and more frequently includes boys as perpetrators and as victims (Espelage & De La Rue, 2013). So, both bullying and sexual harassment can include a power dynamic, and bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment are characterized by the gendered nature of the aggression. But while these behaviors share some of the same antecedents, they likely have some unique predictors as well. Basile et al. (2009) summarize a set of correlates related to promiscuity, deviant arousal, and gender rigidity that have been related to sexual violence but not bullying. It is likely that these and other influences unique to these different kinds of aggression propel a young person to engage in some combination of bullying, homophobic teasing, and/or sexually harassing behaviors. We hypothesize that, consistent with the Bully–Sexual Violence pathway, the relation between bullying perpetration and sexual harassment would be strongest for youth who engage in high rates of homophobic teasing than youth who report less homophobic name-calling.

Although substantial information is available about the risk factors for both bullying and sexual harassment, there is relatively little empirical data demonstrating an association between bullying and later sexual harassment perpetration. Researchers have suggested that bullying may be a precursor to sexual harassment (Pellegrini, 2001; Stein, 1995), but these two problems are recognized, even by students themselves, as related but distinct phenomena (Land, 2003). Only a handful of studies have reported an association between bullying and some form of sexual harassment. One study, by Gruber and Fineran (2008), focused on bullying and sexual harassment victimization, and the other studies focused on bullying and sexual harassment perpetration (DeSouza & Ribeiro, 2005; Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012; Pepler et al., 2006; Pellegrini, 2001); a more recent study examined bullying, sexual harassment, and teen dating violence (Miller et al., 2013). Links between sexual harassment and bullying demonstrated in these studies suggest that youth who engage in one type of aggression (i.e., bullying) may be more likely to engage in the other (i.e., sexual harassment), and that bullying perpetration may lead to sexual harassment perpetration (Miller et al., 2013). No studies to our knowledge have tested homophobic teasing as a potential moderator of the relation between bullying perpetration and later sexual violence perpetration. Thus, the purpose of this article is twofold: (a) to replicate and expand previous research by examining the relation between bullying perpetration at sixth grade and sexual harassment perpetration at eighth grade using a longitudinal design with a large sample of students, and (b) to test the moderating effect of homophobic teasing on the association between middle school bullying and sexual harassment perpetration over time. It is hypothesized that bully perpetration will be more strongly associated with sexual harassment perpetration among adolescents who engage in homophobic teasing. Given the limited literature on the impact of grade and race on this association, these two demographics are treated as covariates in the analyses reported here.

Method

This study is part of a larger, longitudinal research project investigating the intersection of youth bullying experiences and sexual violence perpetration, and evaluating individual and contextual influences on these phenomena.

Participants

The participants in the current study were 979 students from four middle schools (Grades 5 to 7; M Age = 12.61; SD = 0.95 years) in Illinois. The participants include 50.9% females and 49.1% males with approximately 62.3% identifying as African American and 37.7% as White. Sixty percent of the sample was considered low-income students, defined as families receiving public aid or eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunch. No socio-economic status data were available at the individual student level, so this could not be included in the models. For the data utilized in this article, students completed two surveys across 18 months of middle school: once in spring 2008 (Time 1; students were in fifth-seventh grade) and spring 2010 (Time 2; students were in sixth-ninth grades).

Measures

Demographics

Student survey

Participants reported their sex, race/ethnicity, grade, and age in years.

Outcome Measures

Bullying perpetration

The nine-item Illinois Bully Scale assessed the frequency of teasing, name-calling, social exclusion, and rumor spreading (Espelage & Holt, 2001). Students were asked how often in the past 30 days they teased other students, upset other students for the fun of it, excluded others from their group of friends, helped harass other students, and so on. Response options include never, 1 or 2 times, 3 or 4 times, 5 or 6 times, or 7 or more times. Higher scores indicate greater bullying perpetration. The construct validity of this scale has been supported via exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, which has been previously published, scale scores have been strongly correlated with peer nominations of bullying (Espelage, Holt, & Henkel, 2003), and had internal consistency (Time 1 α = .86; Time 2 α = .86) in this study.

Sexual harassment perpetration

The Sexual Harassment/Groping subscale of a modified version of the AAUW Sexual Harassment Survey was used to measure the frequency with which students perpetrated sexual harassment behaviors within the last year (Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012). This subscale contains nine items and assessed perpetration of sexual harassment/groping in the past year (e.g., making sexual comments, spreading rumors, and pulling at clothing of another student). Response options included not sure (1), never (2), rarely (3), sometimes (4), and often (5). Higher scores indicated greater sexual harassment/groping perpetration. We refer to this scale as sexual harassment perpetration throughout the remainder of the manuscript. Alpha coefficients of .72 and .83 were found for Times 1 and 2 in the current study, respectively.

Homophobic teasing perpetration

This five-item agent scale assesses homo-phobic teasing perpetration epithets during the previous 30 days. Students read the following sentence: “Some kids call each other names like homo, gay, lesbo, fag, or dyke. How many times in the last 30 days did YOU say these words to . . . ” and then were asked how often they said these words to a friend, someone you did not like, someone you did not know well, someone you thought was gay, and someone you did not think was gay. Response options include never, 1 or 2 times, 3 or 4 times, 5 or 6 times, or 7 or more times. Construct validity of this scale was supported through factor analyses, and convergence and divergence validity, which have been previously published (Poteat & Espelage, 2005, 2007). Higher scores indicate more homo-phobic teasing, and the scale demonstrated internal consistency at Times 1 and 2 (a = .80).

Procedure

Parental consent

A waiver of active parental consent was approved by the institutional review board and school district administration. Parents of all students enrolled in the school were sent letters informing them about the purpose of the study. Several meetings were held to inform parents of the study in each community. In the early spring of 2008, investigators attended Parent–Teacher conference meetings and staff meetings, and the study was announced in school newsletters and emails from the principals. Furthermore, parents were asked to sign the form and return it only if they were unwilling to have their child participate in the investigation. At the beginning of each survey administration, teachers removed students from the room if they were not allowed to participate, and researchers also reminded students that they should not complete the survey if their parents had returned a form. A 95% participation rate was achieved. Students were asked to consent to participate in the study through an assent procedure included on the cover-sheet of the survey.

Multiple safeguards were implemented to prevent students from becoming upset by the content of the surveys. First, an assent script was read to students that emphasized that completing the task was voluntary and they could skip any question or stop participating at any point. After this script was read, students indicated their assent by signing their name on the survey coversheet. Second, an appropriately trained doctoral-level psychology student was present at every survey administration to provide immediate support for a student, if necessary, and direct him/her to appropriate resources. Third, students were given a card with researcher contact information in case more information about the study or a referral was needed. Multiple self-help resource numbers and websites were included on the card. Fourth, students were reminded verbally about school-based resources available (e.g., guidance counselors) in the beginning and end of survey administration.

Survey administration

Six trained research assistants, the primary researcher, and a faculty member collected data. At least two of these individuals administered surveys to classes ranging in size from 10 to 25 students. Students were first informed about the general nature of the investigation. Next, researchers made certain that students were sitting far enough from one another to ensure confidentiality. Students were then given survey packets and the survey was read aloud to them. It took students approximately 45 minutes on average to complete the survey.

Results

Means and standard deviations for all variables by gender and race are presented in Table 1 and correlations among variables are presented in Table 2. Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine the nature and extent of missing data. To address the issue of missing data for the current sample, a multiple imputation procedure was executed using the PROC MI function in SAS 9.2 (Graham, Cumsille, & Elek-Fisk, 2003). Overall, missingness per item ranged from 0% to 4.7%, with a mean percentage of missing data across all measured variables of 1.7%. Although Luengo, García, and Herrera (2010) suggest that missing data between 1% and 5% are generally manageable, a multiple imputation procedure was employed to preserve the integrity of each group of respondents and create one parsimonious data set.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables.

| Grade Time 1 | Sexual Harassment Perpetration Time 1 | Homophobic Teasing Perpetration Time 1 | Bullying Perpetration Time 1 | Sexual Harassment Perpetration Time 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | |||||

| African American (n = 313) | 6.70 (0.78) | 1.41 (0.49) | 0.10 (1.02) | 0.25 (1.01) | 1.45 (0.50) |

| White (n = 143) | 6.46 (0.77) | 1.22 (0.42) | −0.37 (0.84) | −0.33 (0.88) | 1.44 (0.50) |

| Male | |||||

| African American (n = 327) | 6.65 (0.80) | 1.54 (0.50) | 0.31 (1.03) | 0.27 (1.13) | 1.36 ( .48) |

| White (n = 196) | 6.65 (0.67) | 1.49 (0.50) | −0.05 (1.05) | −0.24 (1.00) | 1.29 (0.45) |

Note. Means are presented with standard deviations in parenthesis. Homophobic teasing and bullying perpetration are presented in z-scores.

Table 2.

Correlations of Study Variables.

| Female | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Grade Time 1 | — | ||||

| 2. Sexual harassment perpetration Time 1 | .12* | — | |||

| 3. Homophobic teasing perpetration Time 1 | .10* | .45** | — | ||

| 4. Bullying perpetration Time 1 | .17** | .41** | .70** | — | |

| 5. Sexual harassment perpetration Time 2 | .17** | .21** | .28** | .35** | — |

| Male | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Grade Time 1 | — | ||||

| 2. Sexual harassment perpetration Time 1 | .14** | — | |||

| 3. Homophobic teasing perpetration Time 1 | .05 | .48** | — | ||

| 4. Bullying perpetration Time 1 | .08 | .40** | .72** | — | |

| 5. Sexual harassment perpetration Time 2 | .04 | .25** | .37** | .39** | — |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

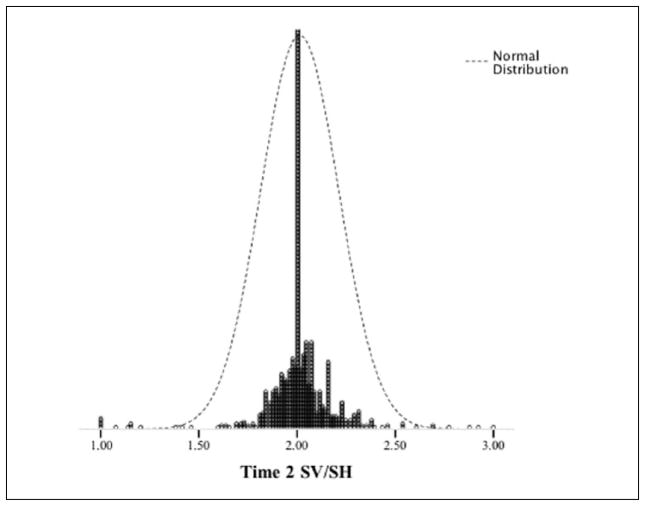

Preliminary examination of the outcome distribution revealed a severe positive skew for the sexual harassment perpetration outcome variable at Time 2 (see Figure 1; skew test statistic = 35; Cramer, 1997) and leptokurtic (kurtosis test statistic = 377; Cramer, 1997). Therefore, this outcome variable was recoded to binary responses based on theoretically driven cut points rather than the observed sample distribution. Thus, this variable was converted to a dichotomous criterion variable, with no perpetration group coded as 0 and a perpetrator group coded as 1 (youth who reported any sexual harassment perpetration). Hierarchical logistic regressions were conducted to model students’ engagement in Time 2 sexual harassment perpetration. In the first step, race (dichotomized with a value of 1 for African American youth and 2 for Caucasian youth) was included as a covariate given the lack of extant literature on race and sexual harassment perpetration. In addition, because this study did not examine ethnic identity or any other race/ethnicity variables beyond students identifying as White or Black, it would be premature to explore race/ethnic differences. Grade was entered as sexual harassment tends to increase as youth age. As the development and refinement of this model continues, it will become important to more fully explore potential differences across race and ethnicity and across the developmental life span. In the second step, predictors measured at Time 1 were utilized, including sexual harassment perpetration, homophobic teasing, bullying, and the interaction between homophobic teasing and bullying. Analyses were conducted separately for females and males.

Figure 1.

The distribution of sexual harassment perpetration with a normal distribution curve imposed (the dotted line).

Note. Response options: 1 = not sure, 2 = never, 3 = rarely, 4 = occasionally, 5 = often.

Logistical Regression Results

For the logistic regression that included girls, the first block of predictors including race and grade was significant, χ2(2, N = 455) = 13.63, p < .01. The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 indicated that these variables accounted for 4% of the total variance. Grade was a significant predictor; specifically, those girls who were older at Time 1 were 1.58 times more likely to be in the sexual harassment perpetrator group at Time 2. The predictors included in the second block provided a statistically significant improvement over the constant-only model in predicting the criterion variable of sexual harassment perpetration, χ2(4, N = 455) = 68.29, p < .01. The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 was .21. Those girls who engaged in bullying behaviors at Time 1 were 3.21 times more likely to engage in sexual harassment perpetration 2 years later. Previous sexual harassment perpetration or the interaction between homophobic teasing and bullying was not significant. The overall prediction rate was 70.5%, with the model doing better predicting non-sexual harassment perpetrators (80.4%) as compared with the sexual harassment perpetration group (58.5%). The regression coefficients for each predictor for the female model are presented in Table 3, and the corresponding coefficients for the male model are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Results for Females, Predicting Sexual Harassment Perpetration at Time 2.

| Variable Entered | B | Wald | Significance | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Block 1 | ||||||

| Grade Time 1 | 0.45 | 13.12 | .00 | 1.58 | 1.23 | 2.01 |

| Race (White) | 0.05 | 0.05 | .83 | 1.05 | 0.70 | 1.58 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| Sexual harassment perpetration Time 1 | 0.25 | 1.01 | .31 | 1.28 | 0.80 | 2.07 |

| Homophobic teasing perpetration Time 1 | 0.22 | 1.99 | .16 | 1.25 | 0.92 | 1.71 |

| Bullying perpetration Time 1 | 1.17 | 11.97 | .00 | 3.21 | 1.66 | 6.22 |

| Homophobic teasing perpetration Time 1 × Bullying perpetration Time 1 | −0.16 | 1.54 | .22 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 1.10 |

Note. The criterion variable of sexual harassment at Time 2 was coded as 0 for not being a perpetrator (no perpetration) and 1 for perpetrators (any perpetration). Race was dichotomized with 1 as African American and 2 as White. CI = confidence interval.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Results for Males, Predicting Sexual Harassment Perpetration at Time 2.

| Variable Entered | B | Wald | Significance | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Block 1 | ||||||

| Grade Time 1 | 0.11 | 0.81 | .37 | 1.11 | 0.88 | 1.42 |

| Race (White) | −0.31 | 2.48 | .12 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 1.08 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| Sexual harassment perpetration Time 1 | 0.19 | 0.24 | .63 | 1.13 | 0.69 | 1.81 |

| Homophobic teasing perpetration Time 1 | 0.51 | 10.95 | .00 | 1.66 | 1.23 | 2.24 |

| Bullying perpetration Time 1 | 1.52 | 25.11 | .00 | 4.58 | 2.52 | 8.30 |

| Homophobic teasing perpetration Time 1 × Bullying perpetration Time 1 | −0.36 | 14.46 | .00 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.84 |

Note. The criterion variable of sexual harassment perpetration at Time 2 was coded as 0 for not being a perpetrator (no perpetration) and 1 for perpetrators (any perpetration). Race was dichotomized with 1 as African American and 2 as White. CI = confidence interval.

For boys, the first block of predictors was not statically significant, indicating that race and grade did not distinguish between sexual harassment perpetration levels at Time 2. While boys of color have been disproportionally represented in rates of bullying perpetration in extant literature (Carlyle & Steinman, 2007; Low & Espelage, 2013), our findings did not support this.

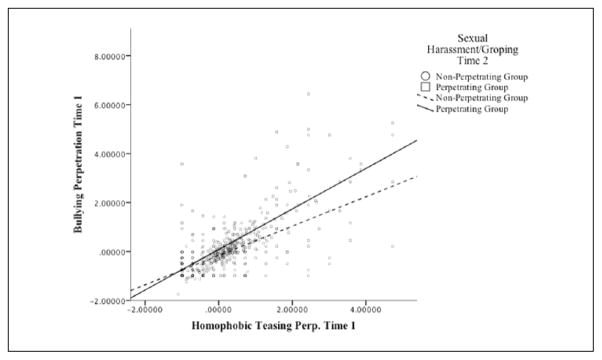

The predictors utilized in the second block significantly predicted the criterion variable of sexual harassment perpetration, χ2(4, N = 523) = 103.69, p < .01. The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 indicated the model accounted for 26% of the total variance. The overall prediction rate was 73.4%, with the model doing better predicting non-sexual harassment perpetrators (90.3%) as compared with the sexual harassment perpetration group (39.7%). Boys who engaged in homophobic teasing were 1.66 times more likely to engage in sexual harassment perpetration at Time 2, and those boys who engaged in bullying behaviors were 4.60 times more likely to engage in sexually harassing behaviors 2 years later. The interaction between homophobic teasing and bullying at Time 1 was also significant, which supported our hypothesis that youth would be less likely to engage in later sexual harassment if they had low levels of homophobic teasing (β = .70). The interaction was plotted in an effort to better understand this relationship (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction between homophobic teasing perpetration and bullying perpetration at Time 1 on sexual harassment perpetration at Time 2 for males.

The graph displayed in Figure 2 provides a visual description of the interaction between bully perpetration and homophobic name-calling, and classification of non-perpetrator or perpetrator of sexual harassment (none vs. some). The lines cross just below the mean values for bullying and homophobic teasing, suggesting that those youth who engage in both of these behaviors at lower levels at Time 1 are less at-risk of being in the sexual harassment perpetrator group 2 years later. However, as hypothesized, high levels of bullying perpetration and high levels of homophobic name-calling at Time 1 was associated with greater risk of being a perpetrator of sexual harassment at Time 2.

Discussion

The literature has documented numerous negative health impacts from both bullying (Espelage & Holt, 2013) and sexual harassment (AAUW Educational Foundation, 2011; Fineran & Bennett, 1998). Homophobic teasing perpetration is commonplace in middle schools and creates an environment that promotes hegemonic masculinity. The fact that there is a dearth of literature examining the links between common behaviors among school age youth—bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment perpetration—may be a function of the fact that researchers in each field have not examined all three constructs in the same study. In addition, only a few bullying prevention programs address sexual harassment components for middle school youth (Second Step, Committee for Children, 2008). As such, this study addresses an important gap in the literature by examining how bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment are related. These findings inform school-level bully prevention efforts to prevent the onset of sexual harassment perpetration.

Sexual harassment was the outcome of focus for this study rather than forced contact acts of sexual violence like rape, mainly because those more severe forms of sexual violence were less likely to be endorsed by middle school students in the sample. We tested the Bully–Sexual Violence Pathway, which posits that youth who engage in high levels of bullying and homophobic teasing perpetration would report perpetrating sexual harassment over time as they progress through middle school, a time when these phenomena increase (Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012). The current findings provide support for the Bully–Sexual Violence Pathway theory for middle school boys, but not girls. Boys who reported bully perpetration at Time 1 were more likely to report sexual harassment measured 2 years later. In addition, homophobic teasing moderated the relation between bullying perpetration and later sexual harassment perpetration, such that boys who reported high levels of bullying behaviors and also reported concurrent high levels of homophobic teasing were more likely to report sexual harassment over time in comparison with boys who engage in both low levels of bullying and homophobic name-calling. When boys are elevated on both of these domains, they are at an increased risk of later sexual harassment perpetration, suggesting that to prevent sexual harassment, homophobic name-calling must be addressed. Of note, Time 1 sexual harassment was not a significant predictor of Time 2 sexual harassment when Time 1 bullying and homophobic teasing was included in the model. This finding is not surprising and suggests that explaining sexual harassment perpetration at Time 2 should consider both bullying and homophobic teasing perpetration rather than simply considering prior levels of sexual harassment perpetration.

The gendered nature and relations among bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment behaviors is worthy of note. For adolescents, particularly for males, there is more pressure to adhere to a restricted range of gender expression. Attacks against perceived deviations from this standard, or implications that such deviations are worthy of ridicule, take the form of homophobic teasing for younger students (Poteat, Kimmel, & Wilchins, 2010). This teasing, which can be sexual in nature, may then elevate to sexual harassment behavior later when coupled with bullying behaviors. When this bullying behavior occurs with concurrent homophobic teasing among boys, the escalation of this as they get older is likely to present as sexual harassment. The current study’s findings highlight the need for prevention efforts to specifically target biased-based teasing behaviors and gender-based bullying, particularly for male adolescents for whom homophobic teasing, and the interaction between homophobic teasing and bullying, was related to later sexual harassment behaviors.

Although homophobic teasing was not a moderator of the association between bullying perpetration and sexual harassment for girls, there was a direct effect between these two variables. Consistent with Pellegrini’s (2001) study, bully perpetration was associated with sexual harassment perpetration over the 2-year study period for girls after controlling for grade and race. Further, girls also reported less engagement in homophobic teasing perpetration in comparison with boys, which may explain why it is moderating the association between bullying and sexual harassment for boys only. However, it is plausible that these girls are hearing the homophobic epithets among the boys and are engaging in sexual harassment perpetration as a reaction. Thus, future studies should examine not only self-reports of homophobic teasing perpetration and victimization, but the extent to which youth hear this language and how this impacts the development of sexual harassment.

This study has a few limitations. First, the sexual harassment outcome examined in this study included mostly non-contact harassing behaviors with some touching or groping items and unwanted sexual commentary. We could not include more severe types of sexual violence, such as forced sexual activity. Three such items were included in the larger study this article was drawn from; however, only 1% to 3% of the population reported engaging in forced sexual contact (e.g., forcing others to kiss or touch one’s body parts). We suspect reporting of these items will increase for males as they age, based on previous studies showing that males are more likely than females to perpetrate these more severe types of sexual violence and that sexual violence perpetration is occurring in late adolescence and early adulthood (Gruber & Fineran, 2008). Second, our sampling relied on single-informants for constructs, which introduces mono-informant bias, and in turn, increases the risks of over-attributing relationships among key constructs. Finally, the way in which the Bully/Sexual Violence pathway theory is conceptualized in this study is heteronormative given that the majority of youth identified as heterosexual. Thus, the same- and opposite-sex gendered dynamics of this theory are an avenue ripe for research. Future research that includes some of the unique correlates of sexual violence (e.g., deviant sexual arousal) in models examining the relationship between bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment/violence may be helpful to further tease out the factors that lead some youth to begin sexual harassing behavior.

While additional research is needed to fully understand the relations among these forms of aggression among more ethnically and racially diverse populations, these findings suggest a promising strategy to prevent sexual harassment may be to focus on the gendered aggressive acts that precede it. As found in previous research, negative peer relationships, characterized by bullying and homophobic teasing, set the stage for later difficulties in opposite-sex relationships (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000). This study may be demonstrating the beginning of a developmental trajectory for some bullies is associated with sexual harassment perpetration 2 years later. Early adolescence, when young people are beginning to form peer relationships and their sexual identities, is good timing for primary prevention efforts. This study suggests that primary prevention efforts might even need to start before middle school, given the adolescents in this study reported perpetrating sexually harassing behaviors in Time 1 data collection at the beginning of middle school.

This study extends the work of Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger (2012) by examining the association between bullying and sexual harassment over 2 years of middle school, and also demonstrating a moderating effect of homo-phobic teasing on the relation between bullying and sexual harassment perpetration of boys. These results provide support for the Bully/Sexual Violence Pathway theory to explain male adolescents’ use of bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment in middle school and their relationship to each other over time. Future research should seek to replicate these findings among racially and ethnically diverse and same-sex attracted populations. It would be useful to follow adolescents into teenage and young adult years, to examine the characteristics of adolescent bullies and homophobic teasers for whom sexually harassing behaviors are sustained over time. Future studies should also consider the sex of the perpetrator and victim. For example, males who bully only female victims may be more likely to go on to perpetrate sexual harassment or other forms of sexual violence against girls/women than those males who bully only males or both males and females. As we continue to refine our understanding of how these forms of gendered aggression are related to one another, this study suggests prevention efforts for bullying and sexual harassment should address the overlapping role of homophobic teasing to better link prevention messages for these forms of aggression.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) declared receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funded by Centers for Disease Control #1U01/CE001677 (Espelage, PI)

The authors acknowledge the passing of their co-author Merle E. Hamburger who passed away when this article was under preparation. This article is dedicated to his memory for his dedication and contributions to youth violence and sexual violence research and prevention.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Association of University Women Educational Foundation. Hostile hallways: Bullying, teasing and sexual harassment in school. Washington, DC: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC. Sexual violence in the lives of girls and women. In: Kendall-Tackett K, editor. Handbook of women, stress, and trauma. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2005. pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Black MC, Simon TR, Arias I, Brener ND, Saltzman LE. The association between self-reported lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse and recent health-risk behaviors: Findings from the 2003 national youth risk behavior survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.001. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Espelage DL, Rivers I, McMahon PM, Simon TR. The theoretical and empirical links between bullying behavior and male sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:336–347. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.06.001. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Saltzman LE. Sexual violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Espelage DL. Homophobic name-calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents. Social Development. 2014 Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Hogan M, Ireland M. Adolescent sexual aggression: Risk and protective factors. Pediatrics. 1997;100:e7. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.e7. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/100/6/e7.full.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Safe Schools Coalition & 4-H Center for Youth Development, University of California, Davis. Consequences of harassment based on actual or perceived sexual orientation and gender non-conformity and step to making schools safer. Davis, CA: Authors; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE, Steinman KJ. Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. Journal of School Health. 2007;9:623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Children. Second Step: Student success through prevention program. Seattle, WA: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Furman W, Konarski R. The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescents. Child Development. 2000;7:1395–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer D. Basic statistics for social research: Step-by-step calculations and computer techniques using minitab. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza ER, Ribeiro J. Bullying and sexual harassment among Brazilian high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1018–1038. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL. Bullying prevention: A research dialogue with Dorothy Espelage. Prevention Researcher. 2012;19:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Aragon SR, Birkett M, Koenig BW. Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: What influence do parents and schools have? School Psychology Review. 2008;37:202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, Hamburger ME. Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, De La Rue L. Examining predictors of bullying and sexual violence perpetration among middle school female students. In: Russell B, editor. Perceptions of female offenders: How stereotypes and social norms affect criminal justice responses. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2:123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK. Suicidal ideation and school bullying experiences after controlling for depression and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK, Henkel RR. Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development. 2003;74:205–220. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00531. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Low S, De La Rue L. Relations between peer victimization subtypes, family violence, and psychological outcomes during adolescence. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Low SK, Anderson C, De La Rue L. Bullying, sexual, and dating violence trajectories from early to late adolescence. 2014. Report submitted to the National Institute of Justice Grant #2011-MU-FX-0022. [Google Scholar]

- Faris R, Felmlee D. Status struggles: Network centrality and gender segregation in same- and cross-gender aggression. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:48–73. doi: 10.1177/0003122410396196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran S, Bennett L. Teenage peer sexual harassment: Implications for social work practice in education. Social Work. 1998;43:55–64. doi: 10.1093/sw/43.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fisk E. Methods for handling missing data. In: Schinka JA, Velicer W, editors. Research methods in psychology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 2003. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber JE, Fineran S. Comparing the impact of bullying and sexual harassment victimization on the mental health and physical health of adolescents. Sex Roles. 2008;59:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9431-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GC, Barongan C. Prevention of sexual assault: Sociocultural risk and protective factors. American Psychologist. 1997;52:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Sallquist J, DiDonato M, Fabes RA, Martin CL. Aggression by who-aggression toward whom: Behavioral predictors of same and other-gender aggression in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:1450–1462. doi: 10.1037/a0027510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, Espelage DL. Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R. Pornographic lives. Violence Against Women. 1995;1:32–54. doi: 10.1177/1077801295001001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land D. Teasing apart secondary students’ conceptualizations of peer teasing, bullying and sexual harassment. School Psychology International. 2003;24:147–165. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0143034303024002002. [Google Scholar]

- Low S, Espelage DL. Differentiating cyber bullying perpetration from other forms of peer aggression: Commonalities across race, individual, and family predictors. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3:39–52. doi: 10.1037/a0030308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luengo J, García S, Herrera F. A study on the use of imputation methods for experimentation with radial basis function network classifiers handling missing attribute values: The good synergy between RBFNs and event covering method. Neural Networks. 2010;23:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2009.11.014. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM. Predictors of naturalistic sexual aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:953–962. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Addison T, Koss M. Pornography and sexual aggression: Are there reliable effects and can we understand them? Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:26–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Williams J, Cutbush S, Gibbs D, Clinton-Sherrod M, Jones S. Dating violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: Longitudinal profiles and transitions over time. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:607–618. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9914-8. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD. The roles of dominance and bullying in the development of early heterosexual relationships. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2:63–73. doi: 10.1300/J135v02n02_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Long JD, Solberg D, Roseth C, Dupuis D, Bohn C, Hickey M. Bullying and social status during school transitions. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Craig W, Connolly JA, Yulie A, McMaster L, Jiang D. A developmental perspective on bullying. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:376–384. doi: 10.1002/ab.20136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat PV, Espelage DL. Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) Scale. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:513–528. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.2005.20.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:175–191. doi: 10.1177/0272431606294839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Kimmel MS, Wilchins R. The moderating effects of support for violence beliefs on masculine norms, aggression, and homophobic behavior during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;21:434–447. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Rivers I. The use of homophobic language across bullying roles during adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I. The bullying of sexual minorities at school: Its nature and long-term correlates. Educational and Child Psychology. 2001;18:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Robers S, Kemp J, Truman J. Indicators of school crime and safety: 2012. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, & Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2013. NCES 2013-036/NCJ 241446. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Espelage DL, Rivers I. Does it get better? Developmental trends in peer victimization and mental health in LGB and heterosexual youth—Results from a nationally representative prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013;131:423–430. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JP, Espelage DL. Inequities in educational and psychological outcomes between LGBTQ and straight students in middle and high school. Educational Researcher. 2011;40:315–330. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11422112. [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin PC, Berger C. Who bullies whom? Social status asymmetries by victim gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:473–485. doi: 10.1177/0165025408093667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein N. Sexual harassment in school: The public performance of gendered violence. Harvard Educational Review. 1995;65:145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the national violence against women survey. National Institute of Justice; 2006. NCJ 210346. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/210346.pdf. [Google Scholar]