Abstract

With the development of endoscopic techniques, the treatment of tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) has made marked progress. As surgical intervention is often not an advisable option due to advanced malignancy and poor performance status of the patients, bronchoscopic intervention provides a good choice to palliate symptoms and reconstruct the airway and esophagus. In this review, we focus on the application of interventional therapy of TEF, especially the application of airway stenting, and highlight some representative cases referred to our department for treatment.

Keywords: Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), interventional therapy, airway stenting, esophageal stenting, efficacy

Introduction

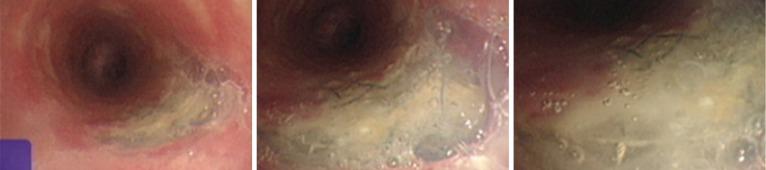

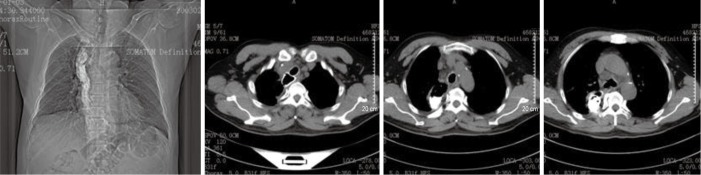

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) occurs as a common congenital deformity or secondary to pathologic injury from diseases such as carcinoma (1,2). TEF is identified by an abnormal connection (fistula) between the esophagus and trachea and is the most common type of airway fistula. Typical symptoms in case of TEF are choking following food intake, severe coughing, feeding disorders, and unmanageable pneumonia (1,3). The quality of life of patients with TEF is poor. Moreover, the life expectancy of the patients without proper treatment may be measured in weeks. Esophageal malignancy is the main cause of TEF (4,5), with tumor invasion through the wall of the esophagus and trachea leading to formation of a fistula. TEF usually develops during or after completing radiation and chemotherapy with subsequent tumor necrosis (6) (Figure 1). In addition, the persistent pressure to the wall of esophagus and airway after esophageal stenting is also an important cause (7) (Figure 2).

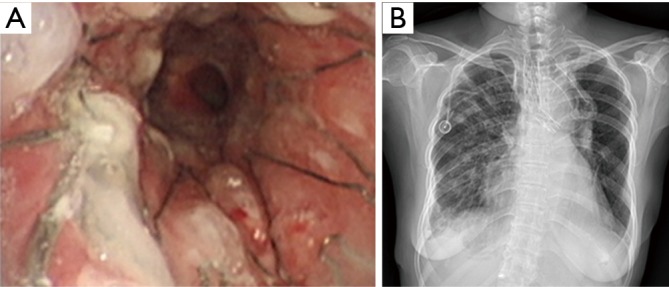

Figure 1.

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) developed after completing radiotherapy for esophageal carcinoma.

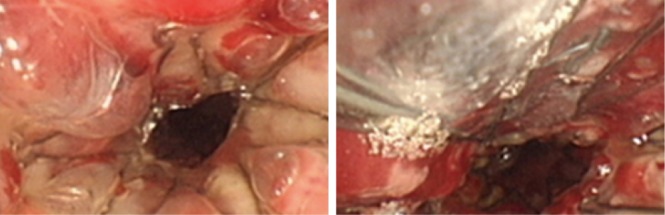

Figure 2.

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) developed after completing esophageal stenting.

The diagnosis of TEF is not difficult based on medical history, clinical manifestations, radiographic examination, and endoscopy (8). Thin-section chest computed tomography (CT) scan and three-dimensional reconstruction, as well as, radiographic examination with oral or intravenous contrast medium aids in the exact localization of the fistula orifice. Bronchoscopy and endoscopy, as the main methods to diagnose TEF, are able to identify the fistulas in most cases. However, recognition of the tracheal or bronchial opening in smaller fistulas can be challenging. Both orally administered Methylene Blue before bronchoscopy and observation of bubbles leaked from the airway are helpful to identify small fistulas (9).

By now, the main treatments for TEF are as follow: (I) interventional treatment with bronchoscopy and endoscopy are the primary therapeutic options, which can alleviate symptoms and prolong survival (4,10); (II) surgery, which is performed rarely on patients with benign TEF (bTEF) because of the risk and the difficulty. The surgical procedures including fistula repair, fistula closure with pedicled muscle flap or omentum major, esophageal bypass surgery and lesion resection (11); (III) general treatment, such as gastrostomy, jejunostomy, indwelling gastric-tube, or jejunal-tube, antibiotics, elimination of airway secretions, and intravenous hyperalimentation.

The main interventional therapy of TEF

The interventional therapy technique

Currently, the treatment of TEF is predominantly interventional and not surgical. The main techniques are: (I) esophageal and/or airway stenting, which is effective to seal the fistula and prevent the leakage of liquid or gas. Meanwhile, it is helpful for healing the fistula in patients with bTEF, and therefore, has been the most common approach (12); (II) closure with local injection of biologic glue or chemical glue can be used in fistulae with a small orifice or combined with stenting, however, the method is uncommonly used owing to its temporary effect and dissolution of coagulum after 2 weeks which leads to recanalization of the fistula (13); (III) laser and argon plasma coagulation (APC) thermal ablation, which are only applied to small fistula orifice. Considering the possibility to cause enlargement of the fistula, the technique should be used with caution (14,15).

Taken together, esophageal and/or airway stenting via endoscopic techniques is by far the optimal clinical option.

Stenting strategy in TEF

Esophageal stenting

Esophageal stenting alone is a good choice to close the fistula orifice in the lower esophagus of TEF patients, especially for those with esophageal stenosis but without airway stenosis. Preoperative endoscopy is used to evaluate the area of lesion, size of fistula, and degree of stenosis. Based on the endoscopic images, the stent length and diameter can be determined. The stent should cover beyond proximal and distal fistula margins, and be wide enough to press firmly against the esophageal wall. Basically, the guidance techniques of esophageal stenting using endoscopic or radiologic approach are simple. In general, most patients can benefit from esophageal stenting and resume their diet after the operation (16,17). However, both displacement of the esophageal stent and expansion of orifice adversely affect closure of the fistula. Esophageal stent replacement or airway stenting should be considered under this circumstance.

Esophageal stent combined with airway stent

Double stenting of the trachea and esophagus is recommended under some conditions. These situations include: (I) esophageal stenting, which might lead to exacerbation of the airway stenosis. In this case, airway stenting should be placed first and followed by esophageal stenting; (II) TEF induced by esophageal stenting is common and we prefer airway stenting first, and then, placement of a new esophageal stent; (III) for the TEF without obvious esophageal stenosis, stent migration is a common complication after esophageal stent placement. To avoid stent displacement, the upper margin of esophageal stent should be placed higher than airway stent’s upper margin; (IV) in those with a huge fistula, whose diameter is larger than 20 mm, esophageal stenting only is not sufficient for therapy. Besides, the stent is likely to migrate into tracheal lumen. Dual stenting is necessary to prevent dislocation and achieve a therapeutic effect.

Airway stenting

In patients where esophageal stents are not indicated or are unable to be placed, airway stenting alone should be considered. The main indications are as follow: (I) the TEF sits in the upper esophageal, especially for those proximal to esophageal entrance; (II) in cases where the distal end of fistula completely occludes the esophageal lumen and the guide wire cannot be placed into gastric cavity; (III) esophageal disease, which might lead to esophageal rupture after esophageal stenting.

The airway stent in the treatment of TEF

Selection of airway stent

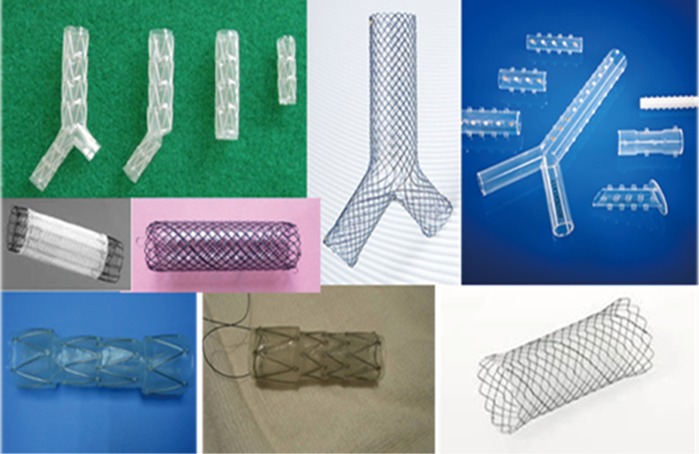

There are a variety of airway stent types that are available to the treatment of TEF (Figure 3). The ideal stent should meet the following requirement: (I) cover the fistula orifice completely and fit perfectly in the tracheal wall; (II) press firmly against the tracheal wall to prevent dislocation; (III) the membrane of the metallic stent is secure and durable; (IV) the stent is able to keep a certain tension for a long period; (V) can be placed and withdrawn easily.

Figure 3.

Various kinds of airway stenting for tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF).

In general, the stents can be divided into two groups according to the material they are made of: membrane-covered metallic stent and silicone stent. The former often has self-expandable properties, which can adapt very well to kinked airways and be suitable for almost all types of TEF. It can be inserted easily with good efficacy, however esophageal secretions tend to spill into the tracheal lumen resulting in an irritating cough. Long-term complications include: membrane damage or dislocation, metal fatigue, and granulation tissue formation. The most commonly used silicone stent is the Dumon stent (18). The Dumon stent is characterized by durability, lasting effect, and good fistula closure. Furthermore, the esophageal secretions are relatively difficult to spill into airway compared to the metallic stent. However, drawbacks include that the silicone stent is specially designed with outer studs (to prevent migration), which may influence the sealing effect. Secondly, the Dumon stents are harder to insert than the metallic stent. Thirdly, the size of fistula orifice might be increased when the stent is released.

Based on the above, the following recommendations should be considered when choosing a stent: (I) if the Dumon stent fits well to surrounding wall, this silicone stent will be the best choice for sealing a longer time and achieving better efficacy; (II) as such, the TEF which is attributed to metal stenting or combined with benign airway stenosis are indications for silicon stenting; (III) in conditions where the silicone stent is difficult to insert or the insertion might enlarge the orifice, use of a metal stent is the better option; (IV) for those where the orifice sits in the upper airway and its’ diameter is more than 18 mm, the metallic stent is the best choice.

Personalizing the design choice of the airway stent

Dependent upon the site of the fistula orifice, the types of airway stents should be chosen for the individual: straight and hourglass-shaped stents are commonly used in high proximal TEF while Y-shaped or L-shaped stents are usually used in lower airway fistula. The length of stent is determined according to the lesion area. The stent should cover at least 20 mm beyond the lesion, and even cover more than 20 mm of proximal and distal margins of the fistula for large orifice. The stent diameter depends on the internal diameter (average of across and vertical diameter) of the normal airway. The stent should be 10–20% larger in diameter than the internal airway adjacent to fistula orifice. To avoid stent displacement, about 5 mm of the both upper and lower margins of straight stents usually remain uncovered. The Y-shaped and L-shaped stents will be preferred in those without obvious airway stenosis.

Post-interventional management

The metallic stent is placed using the flexible or rigid bronchoscope via a special introducer. For silicone stents, deployment under general anesthesia and with rigid bronchoscopy is usually necessary. Long-term complications of stenting, such as stent migration, granulation tissue formation, and retained secretions, are reported. Therefore, it’s essential to perform maintenance bronchoscopy when indicated. Timely elimination of secretions, repositioning the stent after migration, and treating granulation tissue with forceps, laser, or cryotherapy are effective measures to improve complicated conditions. As most of fistula orifices cannot be closed completely, stent replacement and maintenance is sometimes necessary for sealing the fistulae orifice. Therefore, the original stent often must be replaced in time if the following conditions occur: original stent leads to severe complications; tension of stent decreased; or stent failure to work because of enlarged fistulae.

Assessing the efficacy of airway stent

For TEF, the primary goal of therapy is closure of fistula between digestive and respiratory fistulas. Most of the fistula cannot be approached surgically. Moreover, medication treatment is unable to cure the disease. The therapy of TEF is always a challenge in medicine. By far, closure of the fistula with stenting is the ideal method. Airway stenting is indispensable for almost all TEF, except for those where the fistula orifice is located in middle and distal esophagus and without main airway stenosis (esophageal covered stent only is adequate).

Airway stenting has become the most effective palliative treatment method. It not only may prevent or reduce abnormal communications, but also relieve the airway stenosis. These techniques have improved patients’ quality of life dramatically with most patients able to resume liquid or semi-liquid diets after airway stenting. The insertion and removal of stents are not limited by patients’ physical condition or age, and the process is highly safe. Therefore, patients are able to have new stents placed as required.

The airway covered metallic stent is applied in TEF earlier and its’ efficacy in fistula closure has been confirmed in several studies around the world (19,20). Additionally, satisfactory clinical value of double stenting (combined airway metallic stent and esophagus stent) has been reported in several clinical studies (21). Although the application of the Dumon stent in TEF was reported in some small cases studies, the technique did improve symptoms and achieve good clinical outcome (22,23). There was no significant difference in average survival time between the patients with TEF and airway stenosis (23).

From July 2013 to June 2015, our department conducted airway stenting in 61 patients, including 43 metallic stenting and 18 Dumon stents. To our knowledge, there is no uniform standard for assessing the efficacy. We evaluated the clinical efficacy based on following criteria: (I) complete response: no leakage of contrast medium after digital radiography, clinical symptoms resolved without recurrence for more than 2 weeks; (II) partial response: minor leakage of contrast medium, clinical symptoms were relived effectively and maintained for more than 2 weeks; (III) failed treatment: severe leakage of contrast medium, no improvement in clinical symptoms. Our data was divided into two groups according to the material of stent. In metallic stent group, there were 28 cases (65.1%) which achieved complete response and 15 cases (34.9%) with a partial response. Among the group, 24 of the 25 cases (96%) who underwent double stenting achieved a complete response. In the silicone stent group, 13 cases (72.2%) obtained a complete response while 5 cases (27.8%) were a partial response. All 10 cases that received double stenting reached complete response. In total, all 61 cases achieved complete response or partial response, which suggested the superiority of airway stenting in TEF treatment. According to our results, double stenting of the trachea and esophagus can achieve the best clinical benefit (rate of complete response approached 100%). Metallic stents and silicone stents show equivalent clinical effects. However, the rate of complete response is slightly higher in silicone stent group (P>0.05).

In conclusion, the closure effect of airway stent is associated with various factors. The apposition between the stent and tracheal wall around the fistula, adequacy of the length of stent, associated coughing that might influence the seal between the stent and airway wall, the complication of airway stenosis, as well as, the presence of an esophageal stent, are all factors that determine the clinical outcome. Therefore, the key to achieve better clinical efficacy is selecting the appropriate stent type, choice and placement of the stent dependent upon the individual patients, and combining with esophageal stenting as possible.

The typical cases

As mentioned above, a total of 61 cases underwent airway stenting in our department. Following are some representative cases, which were referred to our service.

Case 1: A 57-year-old woman, with a history of esophageal carcinoma operation more than three years prior to being seen had esophageal stenting after tumor recurrence. Eight months after esophageal stenting the patient complained of choking after eating for 10 days. The TEF at the upper margin of esophageal stent was found via bronchoscopy (Figure 4). The patient then received an L-shape stainless steel covered stent in trachea and left main bronchus (Figure 5). After airway stenting, the patient resumed a normal diet and achieved complete response. However, seven months after airway stenting, she died from systemic metastases.

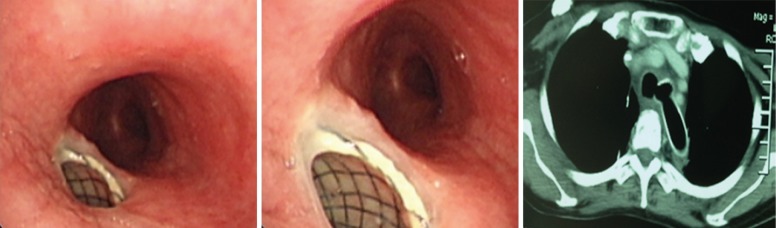

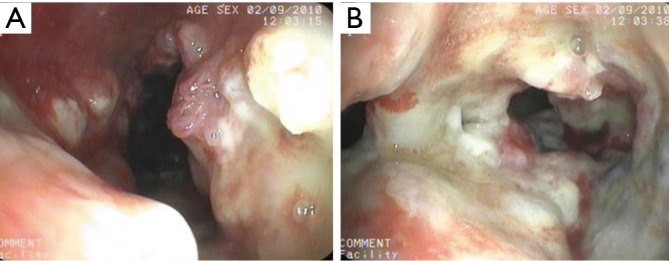

Figure 4.

The tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) caused by esophagus stenting.

Figure 5.

Endoscopic manifestation (A) and chest-radiography finding (B) after L-shaped stainless steel covered stent.

Case 2: A 62-year-old man, with history of radiotherapy for esophageal carcinoma for 11 years, complained of choking while eating for a month prior to being seen by our service. Bronchoscopy revealed that the neoplasm in middle and distal tracheal airway and bilateral main bronchus was observed to have granulation tissue in the wall of the airway, irregular distortion of the lumen, and absence of the normal tracheal carina (Figure 6). Owing to the patient’s condition, we decided to perform airway stenting. The patient received a straight nitinol covered stent in the upper and middle trachea, an L-shaped stainless steel covered stent in lower of trachea and left main bronchus, and a straight stainless steel covered sent in right main bronchus (Figure 7). Upon further investigation of the esophagus by endoscopy, a fistula orifice with a length of 45mm was detected in the middle of esophagus (Figure 8). We therefore placed an esophageal stainless steel covered stent to seal the fistula (Figure 9). After multiple stenting, the airway reconstruction and closure of fistula were achieved (Figure 10). After treatment, the patient could resume a semi-liquid diet with relief from coughing with control of the pulmonary infection. According to our criteria, he achieved a partial response and eventually succumbed from systemic failure three months after treatment.

Figure 6.

The neoplasm in middle and distal of the airway and bilateral main bronchus, fester in wall of the airway, irregular distortion of airway lumen and tracheal carina disappeared.

Figure 7.

A straight nitinol covered stent, a L-shaped stainless steel covered stent and straight stainless steel covered sent were inserted into trachea and bilateral main bronchus, respectively.

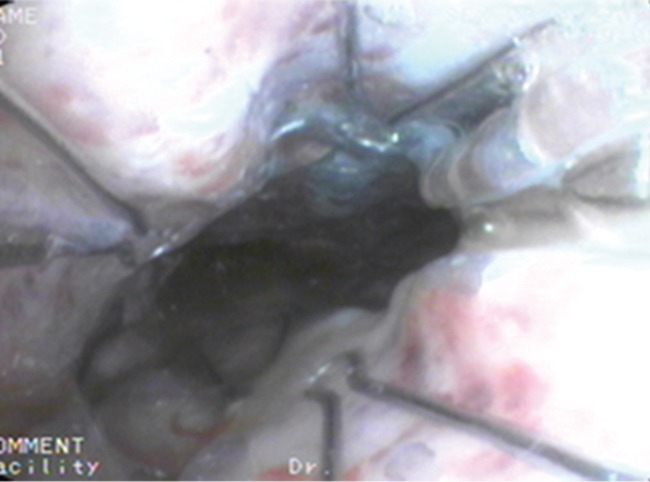

Figure 8.

The tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) in middle of fistula orifice, the airway stent could be seen from the fistula.

Figure 9.

The fistula orifice was covered completely after esophagus stenting.

Figure 10.

The chest imaging after double tracheal and esophageal stenting.

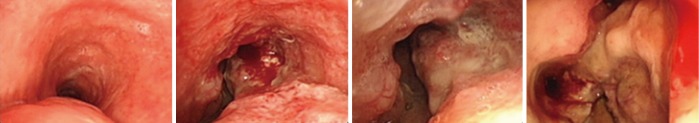

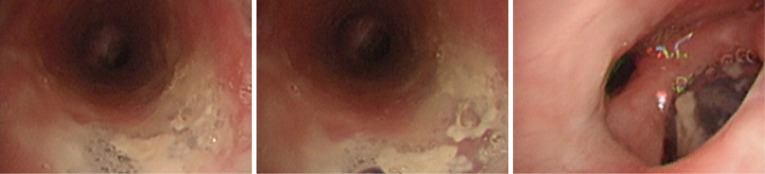

Case 3: A 59-year-old man, with a history of radiotherapy for esophageal carcinoma for 5 years presented with coughing and shortness of breath for 6 months and choking while eating for a month. Bronchoscopy detected the wall of airway was thickened, eroded, and the lumen was irregularly stenotic. The airway communicated with the esophagus through a 30 mm fistula orifice in the left of posterior wall and the carina. The anterior walls of the bilateral main bronchi were distorted, and the remaining bronchi were stenosed by external pressure (Figure 11). We inserted a Y-shaped nitinol covered stent in the trachea and bilateral bronchus under visual control to reconstruct the airway and seal the fistula (Figure 12). The bronchoscope was inserted into esophagus, instead of gastroscopy, and a fistula with the length of 30 mm was detected in the middle of esophagus and the wall of esophagus around it was stiff and stenotic (Figure 13). The patient received a stainless steel covered stent, the diameter of which was 12mm, to seal the orifice dilate the lumen (Figure 14). After stenting, the patient resumed an oral diet. The assessment of him was partial response. However, he finally died from systemic failure 70 days later.

Figure 11.

The airway lumen was stenosis irregularly, the airway was communicated with esophagus through the 30 mm fistula orifice in the left of posterior wall, and the tracheal carina was disappeared.

Figure 12.

The Y-shaped nitinol covered stent was placed in tracheal and bilateral bronchus.

Figure 13.

A fistula 30 mm in the middle of esophagus, through it the airway stent could be detected.

Figure 14.

The esophagus after stainless steel covered esophageal stenting.

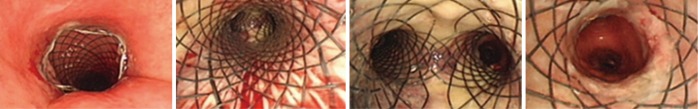

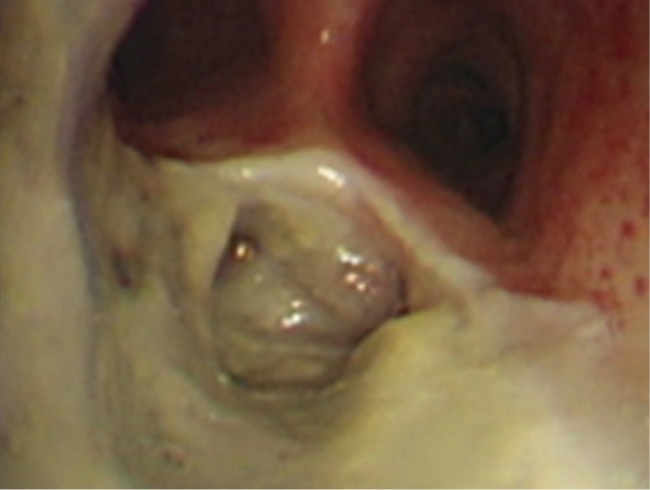

Case 4: A 56-year-old man with an anastomotic stenosis and stenting for 5 months, complained of choking while eating. By bronchoscopy, we could see the fistula in the posterior wall of the middle of the airway and local stenosis by external pressure (Figure 15). The patient underwent Y-shaped silicone stent via rigid bronchoscopy. The stent fit closely to the wall around the fistula orifice (Figure 16). To test the fitness between the stent and airway, the patient was asked to swallow oral contrast and then be investigated as to whether there was leakage. The test result of him is normal and he subsequently resumed a diet (Figure 17). A month after stenting, we could detect that the stent was fit closely with the wall of airway (Figure 18). He achieved complete response based our criteria. The patient has been followed up for eight months and is still eating normally without signs of pulmonary infection.

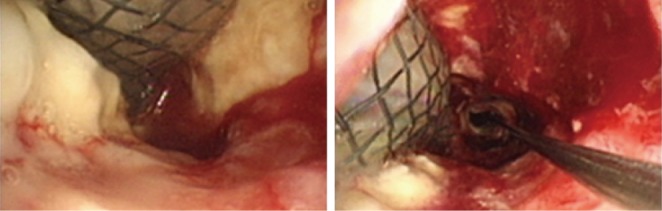

Figure 15.

The bronchoscopy revealed the stenosis, fistula and the upper margin of esophagus stent.

Figure 16.

Y-shaped silicone stent fit closely with the wall around fistula orifice.

Figure 17.

The radiological images showed that no leakage was found after took iodine.

Figure 18.

After esophagus stent dropped off, the silicon stent was fit closely with the wall of airway.

Conclusions

Most TEF is due to malignancy with the patients having a short survival time. The treatment of TEF is a tough challenge. Although the efficacy has been achieved after application of interventional therapy, the treatment strategy should be improved continuously to make the patients live a better and longer time.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Reed MF, Mathisen DJ. Tracheoesophageal fistula. Chest Surg Clin N Am 2003;13:271-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahnoun L, Aloui S, Nouri S, et al. Isolated congenital tracheoesophageal fistula. Arch Pediatr 2013;20:186-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudovsky LM, Koroleva NS, Biryukov YB, et al. Tracheoesophageal fistulas. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;55:868-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hürtgen M, Herber SC. Treatment of malignant tracheoesophageal fistula. Thorac Surg Clin 2014;24:117-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burt M, Diehl W, Martini N, et al. Malignant esophagorespiratory fistula: management options and survival. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;52:1222-8; discussion 1228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balazs A, Kupcsulik PK, Galambos Z. Esophagorespiratory fistulas of tumorous origin. Non-operative management of 264 cases in a 20-year period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:1103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schowengerdt CG. Tracheoesophageal fistula caused by a self-expanding esophageal stent. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filston HC, Rankin JS, Kirks DR. The diagnosis of primary and recurrent tracheoesophageal fistulas: value of selective catheterization. J Pediatr Surg 1982;17:144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott DA. Esophageal Atresia/Tracheoesophageal Fistula Overview. 1993. [PubMed]

- 10.Rodriguez AN, Diaz-Jimenez JP. Malignant respiratory-digestive fistulas. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010;16:329-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, Wain JC, et al. Management of acquired nonmalignant tracheoesophageal fistula. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;52:759-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freitag L, Tekolf E, Steveling H, et al. Management of malignant esophagotracheal fistulas with airway stenting and double stenting. Chest 1996;110:1155-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scappaticci E, Ardissone F, Baldi S, et al. Closure of an iatrogenic tracheo-esophageal fistula with bronchoscopic gluing in a mechanically ventilated adult patient. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rakoczy G, Brown B, Barman D, et al. KTP laser: an important tool in refractory recurrent tracheo-esophageal fistula in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010;74:326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatnagar V, Lal R, Sriniwas M, et al. Endoscopic treatment of tracheoesophageal fistula using electrocautery and the Nd:YAG laser. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang BT, Li GH, Li RH, et al. The value of clinical application of covered esophageal stent in the treatment of malignant esophageal stenosis and esophago-tracheal fistula under endoscope. Modern Digestion & Intervention 2014:222-225. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang TX, Jiang RH. 42 cases observation of covered stent placed by endoscopy to treat tracheoesophageal fistula after esophageal radiotherapy. China Journal of Endoscopy 2014:401-403. [in Chinese].

- 18.Dumon JF. A dedicated tracheobronchial stent. Chest 1990;97:328-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han XW, Li TX, Wang RL, et al. Cancerous esophagotracheal fistula: treatment of placement with covered self-expanding metallic Stent. Chinese Journal of Radiology 1997:18-20. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koeda K, Ishida K, Sato N, et al. Clinical experiences with the insertion of dynamic stent for the patients with esophago-tracheal fistula due to advanced esophageal carcinoma--two case reports. Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1997;45:1169-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi XW, Zhang XL.16 cases analysis of covered esophageal stenting in the treatment of esophago-tracheal fistula. Chinese Journal of Misdiagnostics 2007:833-834. [in Chinese].

- 22.Mitsuoka M, Sakuragi T, Itoh T. Clinical benefits and complications of Dumon stent insertion for the treatment of severe central airway stenosis or airway fistula. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;55:275-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belleguic C, Lena H, Briens E, et al. Tracheobronchial stenting in patients with esophageal cancer involving the central airways. Endoscopy 1999;31:232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]