Abstract

In adults, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) has been shown to out-perform S100β in detecting intracranial lesions on computed tomography (CT) in mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). This study examined the ability of GFAP and S100β to detect intracranial lesions on CT in children and youth involved in trauma. This prospective cohort study enrolled a convenience sample of children and youth at two pediatric and one adult Level 1 trauma centers following trauma, including both those with and without head trauma. Serum samples were obtained within 6 h of injury. The primary outcome was the presence of traumatic intracranial lesions on CT scan. There were 155 pediatric trauma patients enrolled, 114 (74%) had head trauma and 41 (26%) had no head trauma. Out of the 92 patients who had a head CT, eight (9%) had intracranial lesions. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for distinguishing head trauma from no head trauma for GFAP was 0.84 (0.77-0.91) and for S100β was 0.64 (0.55-0.74; p<0.001). Similarly, the AUC for predicting intracranial lesions on CT for GFAP was 0.85 (0.72-0.98) versus 0.67 (0.50-0.85) for S100β (p=0.013). Additionally, we assessed the performance of GFAP and S100β in predicting intracranial lesions in children ages 10 years or younger and found the AUC for GFAP was 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.86-1.00) and for S100β was 0.72 (0.36-1.00). In children younger than 5 years old, the AUC for GFAP was 1.00 (95% CI 0.99-1.00) and for S100β 0.62 (0.15-1.00). In this population with mild TBI, GFAP out-performed S100β in detecting head trauma and predicting intracranial lesions on head CT. This study is among the first published to date to prospectively compare these two biomarkers in children and youth with mild TBI.

Key words: : computed tomography (CT), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), head trauma, mild traumatic brain injury, S100B

Introduction

A recent systematic review of the literature of clinical research on biomarkers for pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) revealed a flurry of research in the area over the last decade.1 Despite the 99 different biomarkers assessed in over 49 published studies, there is still a lack of any U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved biomarkers for clinical use in children.1 Many of the studies reviewed assessed biomarkers that were not brain specific, collected samples over inconsistent time-points, did not use clinically important outcome measures, and did not report common data elements.

The ability to detect children with intracranial lesions on computed tomography (CT) would contribute significantly to the acute management of children with head trauma and suspected TBI by reducing exposure to ionizing radiation.2,3 Of the markers studied to date, S100β is the most frequently studied in pediatric TBI. S100β is the major low-affinity calcium binding protein in astrocytes that helps regulate intracellular levels of calcium. Pediatric biomarker studies examining serum S100β for intracranial lesions in mild TBI have shown conflicting results. Some have found no association between S100β and intracranial lesions on CT4,5 while others have shown a weak association, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.66 and 0.68.6,7 Although S100β remains promising as an adjunctive marker, its utility in the setting of multiple trauma remains controversial because it is also elevated in trauma patients without head injuries.8–12 This is because it also can be found in non-neural cells, such as adipocytes, chondrocytes, and melanocytes.13,14

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) has been shown to be a promising brain-specific biomarker for mild TBI.15–18 GFAP is a monomeric intermediate protein that was first isolated by Eng and colleagues in 1971 and found in astroglial skeleton in both white and gray brain matter.19 A recently published study in 397 adult trauma patients compared the performance of S100β with GFAP in predicting intracranial lesions on CT in the presence of torso and limb fractures.18 Overall, GFAP out-performed S100β in detecting CT lesions and did considerably better in detecting such lesion in multiple trauma when extracranial fractures were present. GFAP is detectable in serum in less than 1 h after a mild TBI and can distinguish mild TBI patients from other trauma patients.15,18

This study compared the ability of GFAP and S100β to detect intracranial lesions on CT in children and youth with head trauma and also assessed their performance in trauma controls.

Methods

This prospective cohort study enrolled a convenience sample of children and youth (birth to 21 years old) with and without head trauma (Glasgow Coma Scale [GSC] score of 9 to 15) presenting to the emergency department (ED) within 6 h of trauma. The study sites included three EDs: a pediatric Level 1 trauma center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a pediatric Level 1 trauma center in Orlando, Florida, and an affiliated adult Level 1 trauma center in Orlando, Florida. This study was approved by the institutional review board of each institution. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and/or their legal authorized representative prior to enrollment.

Eligibility for the study was determined by the treating physician based on the history of blunt head trauma presenting to the ED within 6 h of injury with an initial GCS score of 9 to 15. Eligibility also was prospectively verified by the research team prior to enrollment. Head trauma patients were further categorized into children with TBI symptoms (loss of consciousness, amnesia, disorientation, or change in behavior) and children without TBI symptoms. Head CT scans were performed at the discretion of the treating physician. Patients were excluded if they: 1) had syncope or seizure prior to their head trauma; 2) had known chronic psychosis, neurological disorder, or active central nervous system pathology; 3) were pregnant; 4) were incarcerated; 5) had spinal cord injury; or 6) had hemodynamic instability.

The trauma control patients included patients presenting to the ED with a traumatic mechanism of injury not involving the head and were hemodynamically stable. The mechanisms of injury were similar to the head trauma group and included orthopedic injuries and motor vehicle collisions (MVCs). The purpose of enrolling trauma controls was to assess the biomarkers against a comparable control group, thereby simulating a real-world setting of trauma.

All initial patient assessments were made by board-certified emergency medicine physicians (mostly pediatric) trained by a formal 1-h session on evaluating patient eligibility. At the time of enrollment, the study team carefully reassessed every patient to ensure that each patient met inclusion criteria and verified any exclusion. Blood samples were obtained from each head trauma and trauma control patient within 6 h of the reported time of injury. A single vial of approximately 5 mL of blood was collected and placed in a serum separator tube and allowed to clot at room temperature before being centrifuged. The serum was placed in bar-coded aliquot containers and stored in a freezer at −70°C until it was transported to a central laboratory where samples were analyzed in batches using sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for GFAP and S100β. After assessment and treatment in the ED, patients were either discharged home or admitted to hospital based on severity of their injuries, and patient management was not altered by the study.

Trauma patients underwent standard CT scan of the head according to the judgment of the treating physician. CT examinations were interpreted by board-certified radiologists who recorded location, extent, and type of brain injury. Radiologists were blinded to the study protocol but had the usual clinical information. Lab personnel running the samples were blinded to the clinical data.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the presence of intracranial lesions on initial CT scan. Intracranial lesions on CT included any acute traumatic intracranial lesions visualized on CT scan such hemorrhages (epidural, subdural, subarachnoid, ventricular, and parenchymal), contusions, edema, and pneumocephalus but excluded facial fractures and isolated skull fractures without intracranial lesions. The secondary outcome measure included the performance of the biomarkers in trauma controls versus head trauma patients.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics with means and proportions were used to describe the data. For statistical analysis, biomarker levels were treated as continuous data, measured in ng/mL, and expressed as medians with interquartile range. Data were assessed for equality of variance and distribution. Logarithmic transformations were conducted on non-normally distributed data. Group comparisons for different CT categories were performed using analysis of variance with multiple comparisons using least significant difference correction. ROC curves were created to explore the ability of the biomarkers to detect intracranial lesions on CT scan. Comparison between dichotomous groups was performed using Mann Whitney U. Estimates of the area under these curves (AUC) were obtained (AUC=0.5 indicates no discrimination and an AUC=1.0 indicates a perfect diagnostic test). Classification performance was assessed by sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). GFAP and S100β cutpoints were selected based on the ROC curve to maximize the sensitivity and correctly identify as many patients with CT lesions as possible. All analyses were performed using the statistical software package PASW 17.0 (IBM Corporation®, Somers NY).

Biomarker analysis

Serum GFAP levels were measured in duplicate for each sample using a validated ELISA platform (Banyan Biomakers Inc., Alachua, FL). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for this assay is 0.030 ng/mL and the upper limit of quantification is 50 ng/mL. The limit of detection LOD is 0.008 pg/mL. Serum S100β levels were measured in duplicate for each sample using an ELISA platform that is for research purposes only (Banyan Biomakers Inc.). The assay calibrators range from 0.016 ng/mL to 2 ng/mL. LOD of the S100β assay at 0.017 ng/mL and the LLOQ at 0.083 ng/mL. Any samples yielding a signal over the quantification or calibrator range were diluted and re-assayed.

Results

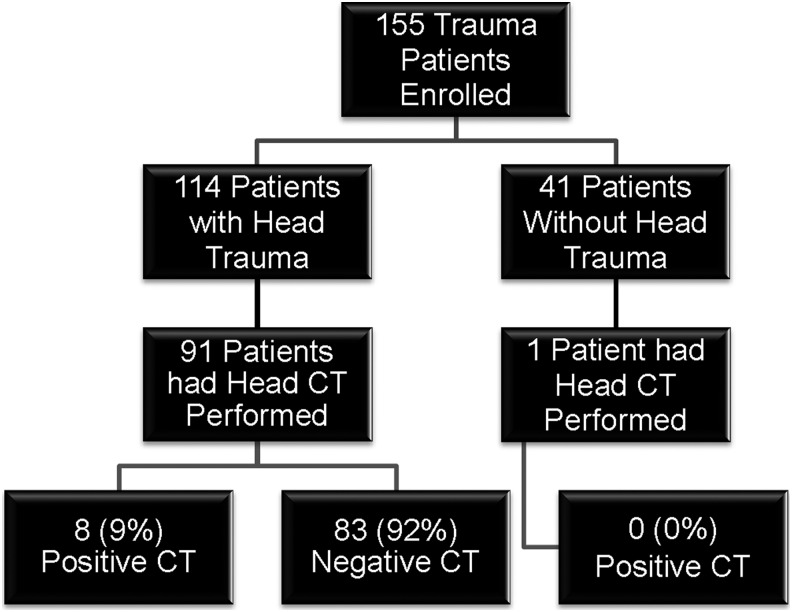

There were 155 children and youth enrolled; 114 (74%) had a head trauma and 41 (26%) were trauma controls. Of the 114 subjects with head trauma, 112 (98%) had a GCS score of 13-15 and two had a GCS score of 9-12. The flow diagram in Figure 1 describes the characteristics and distribution of enrolled patients. CT scan of the head was performed in 92 patients and traumatic intracranial lesions on CT scan were evident in eight (9%), all of whom had a GCS score of 13-15: one had a GCS score of 13, two had a GCS score of 14, and five had a GCS score of 15. A CT scan also was performed in one trauma patient without head injury and it was negative. The mean age of enrolled patients was 13 years, with a range from six months to 21 years, and 65% were male. The distribution of clinical characteristics in each group is presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in the age, gender, race, mechanism of injury, or admission rate between head trauma patients and trauma controls (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of enrolled patients. Flow diagram showing the number of enrolled trauma patients with and without head trauma.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Enrolled Children and Youths

| Characteristics | Head trauma n=114 | Trauma controls n=41 | Total n=155 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years±SD) | 13 (±7) | 13 (±5) | 13 (±7) | 0.824 |

| Range | (0.6-21) | (3-21) | (0.6-21) | |

| Gender (%) male | 76 (67) | 24 (59) | 100 (65) | 0.350 |

| Race (%) | 0.362 | |||

| Asian | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Black | 32 (28) | 18 (44) | 50 (32) | |

| Hispanic | 24 (21) | 5 (12) | 29 (19) | |

| White | 55 (48) | 17 (42) | 72 (46) | |

| Other | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | |

| GCS score in ED (%) | 0.001 | |||

| GCS 9-12 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| GCS 13 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| GCS 14 | 9 (8) | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | |

| GCS 15 | 102 (89) | 41 (100) | 146 (94) | |

| Mechanism of injury (%) | 0.085 | |||

| Motor vehicle crash | 28 (24) | 10 (24) | 38 (24) | |

| Fall | 37 (33) | 23 (56) | 60 (39) | |

| Motorcycle | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Pedestrian struck | 9 (8) | 0 (0) | 9 (6) | |

| Bicycle | 14 (12) | 0 (0) | 14 (9) | |

| Assault | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Sports | 10 (9) | 5 (12) | 15 (10) | |

| Other | 13 (11) | 3 (7) | 16 (10) | |

| Admitted to hospital (%) | 34 (30) | 9 (22) | 43 (28) | 0.408 |

| Lesion types on head CT (%)* | 0.007 | |||

| Epidural hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| Contusion | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (3) | |

| Pneumocephalus | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Skull or basal skull fracture | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | |

| Facial fractures | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) |

Demographic and clinical data for all subjects included in the study. The table describes data from enrolled trauma patients with and without head trauma. Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100

Some patients had a combination of lesions listed.

SD, standard deviation; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ED, emergency department; CT, computed tomography.

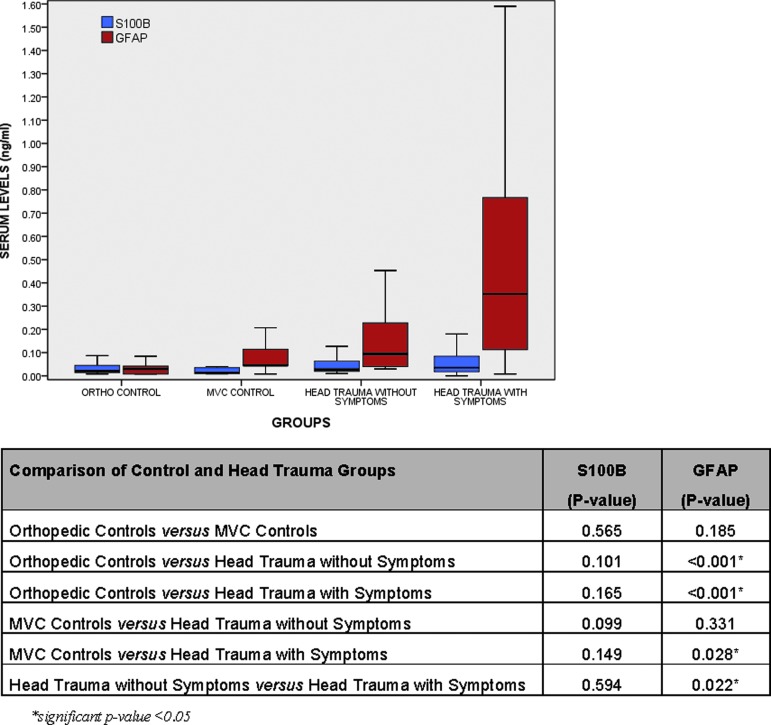

Of the 114 subjects with head trauma, 78 (68%) had TBI symptoms and 36 (32%) had no TBI symptoms. In Figure 2, levels of GFAP and S100β are compared in four groups of trauma patients: 1) orthopedic controls without head trauma; 2) MVC controls without head trauma; 3) head trauma patients without TBI symptoms; and 4) head trauma patients with TBI symptoms. Levels of serum GFAP were significantly different between each of the groups except for MVC controls and head injury without TBI symptoms. Levels of S100β showed no significant differences between the any of the four groups.

FIG. 2.

Boxplot of levels of serum levels of S100β and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) measured within 6 h of trauma in four groups of patients: 1) orthopedic controls without head trauma; 2) motor vehicle collision (MVC) controls without head trauma; 3) head trauma patients without traumatic brain injury (TBI) symptoms; and 4) head trauma patients with TBI symptoms. The median levels for GFAP in each of the groups was 0.03 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.008 - 0.042); 0.05 (IQR 0.05 - 0.16); 0.09 (IQR 0.04 - 0.24); and 0.35 (IQR 0.11 - 0.77), respectively. The median levels for S100β in each of the groups was 0.02 (IQR 0.01 - 0.05); 0.02 (IQR 0.01 - 0.04); 0.03 (IQR 0.02 - 0.07); and 0.03 (IQR 0.02 - 0.08), respectively. Bars represent median serum levels with IQRs of S100β and GFAP (ng/mL; n=32, 9, 36, and 78, respectively). Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

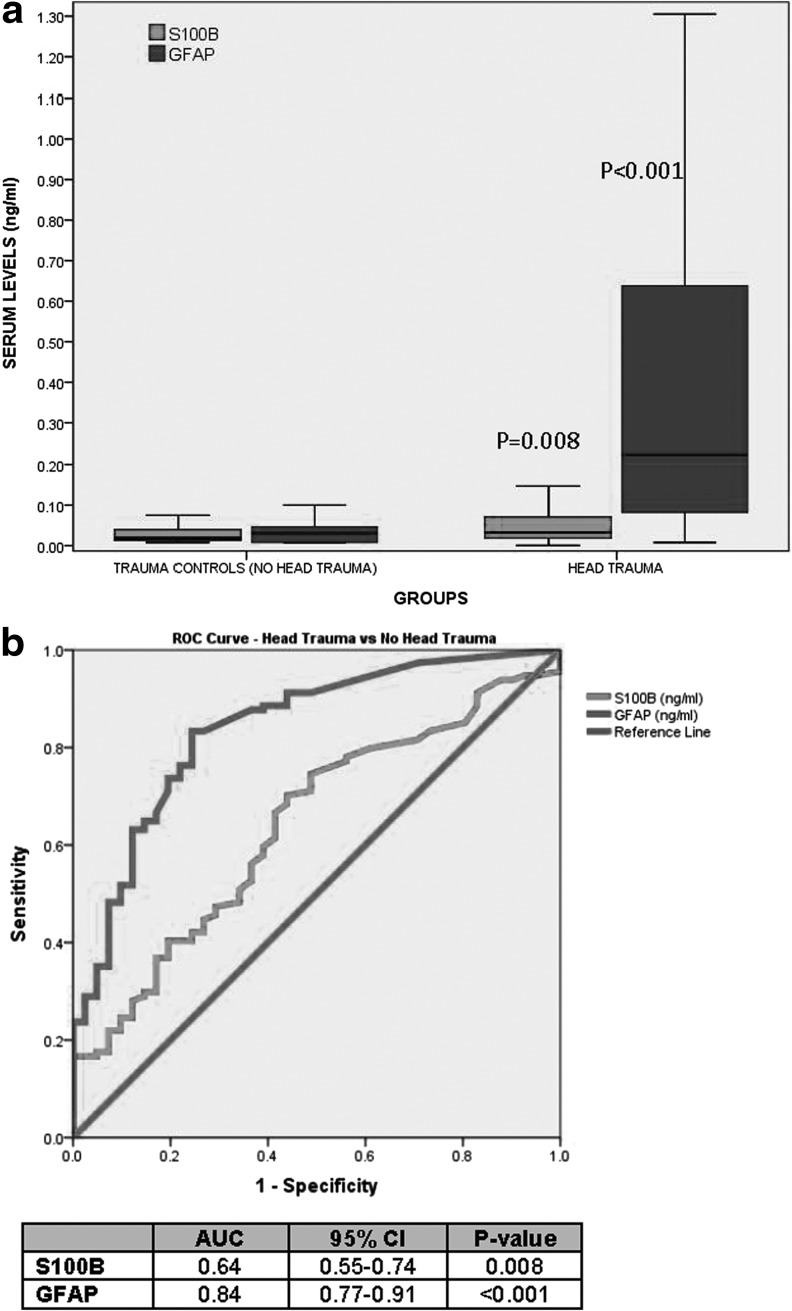

We further compared all head trauma patients versus all trauma controls and found that both GFAP and S100β were significantly higher in patients with head trauma versus no head trauma (p<0.001 and p=0.008 respectively; Fig, 3A). However, the AUC was significantly larger for GFAP 0.84 (95% CI 0.77-0.91), compared with S100β 0.64 (95% CI 0.55-0.74; Fig. 3B). The likelihood ratio for distinguishing head trauma from controls was 5.0 (95% CI 2.2-11.4) for GFAP and 1.5 (1.1-2.1) for S100β.

FIG. 3.

(A) Boxplot of levels of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) versus S100β in children and youths with (n=114) and without head trauma (n=41). The median levels for GFAP in those with and without head trauma was 0.22 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.08 – 0.64) versus 0.03 (IQR 0.01 - 0.06), respectively (p<0.001). The median levels for S100β in those with and without head trauma was 0.03 (IQR 0.02 - 0.07) versus 0.02 (IQR 0.01 - 0.04), respectively (p=0.008). Bars represent median serum levels, with IQRs of S100β and GFAP (ng/mL) measured within 6 h of injury. Both biomarkers were significantly higher in head trauma versus trauma controls. (B) Receiver operating characteristic curve assessing the performance of serum levels of GFAP and S100β in distinguishing trauma patients with and without head trauma. The area under the curve for GFAP was significantly higher than for S100β (p<0.001).

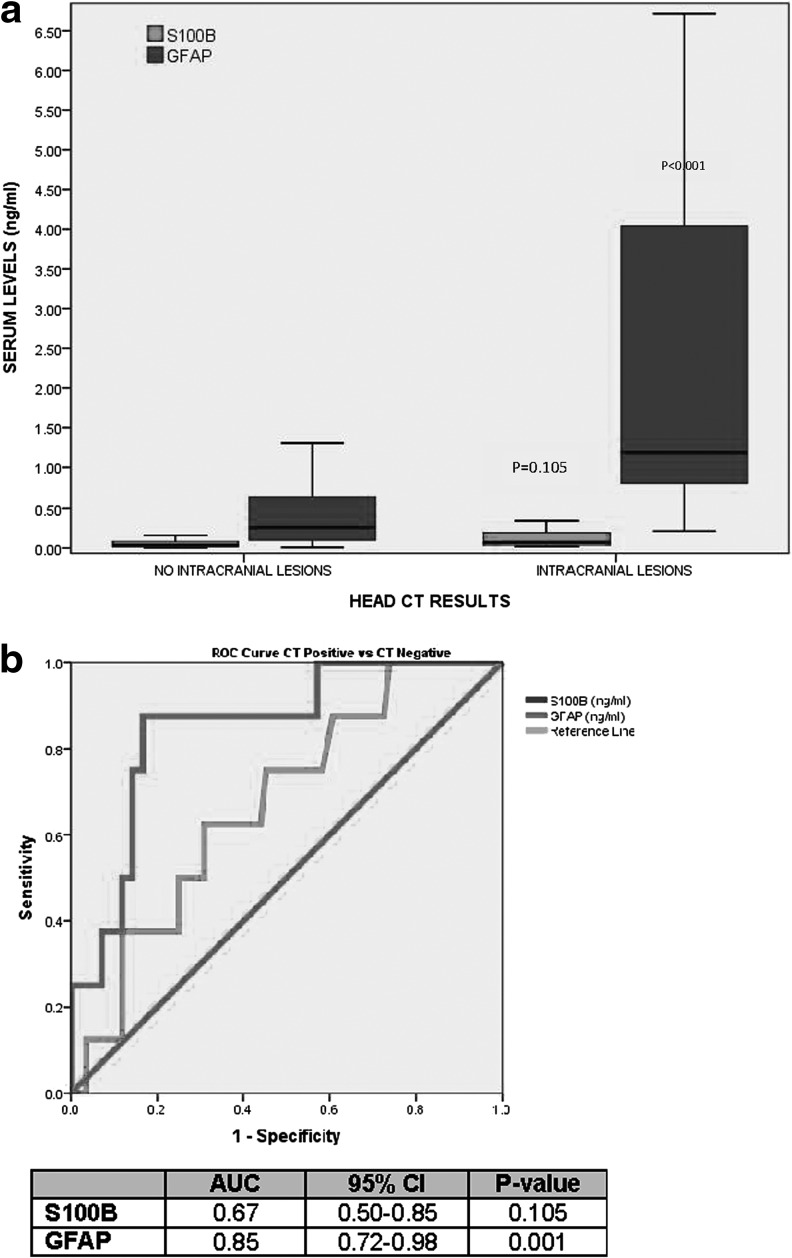

When serum levels of GFAP and S100β were compared in children and youth with traumatic intracranial lesions on CT scan (CT positive) to those without CT lesions (CT negative), GFAP levels were significantly higher in those with lesions than without lesions (p<0.001; Fig. 4A). The AUC for discriminating between CT scan positive and CT scan negative intracranial lesions was 0.85 (95% CI 0.72-0.98) for GFAP versus 0.67 (95% CI 0.50-0.85) for S100β (p=0.013; Fig. 4B). Additionally, we assessed the performance of GFAP and S100β in predicting intracranial lesions in children ages 10 years old or younger (n=25; two with lesions) and found the AUC for GFAP was 0.96 (95% CI 0.86-1.00) and for S100β was 0.72 (0.36-1.00). In children younger than 5 years old (n=15; two with lesions) the AUC for GFAP was 1.00 (95% CI 0.99-1.00) and for S100β was 0.62 (0.15-1.00).

FIG. 4.

(A) Boxplot of levels of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) versus S100β in children and youths with (n=8) and without traumatic intracranial lesions on computed tomography (CT; n=84). The median levels for GFAP in those with and without lesions was 1.19 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.78 - 5.13) versus 0.25 (IQR 0.10 - 0.63), respectively (p=0.001). The median levels for S100β in those with and without lesions was 0.08 (IQR 0.03 - 0.19) versus 0.04 (IQR 0.02 - 0.08), respectively (p=0.105). Bars represent median serum levels with IQRs of S100β and GFAP (ng/mL) measured within 6 h of injury. (B) Receiver operating characteristic curve assessing the performance of serum levels of GFAP and S100β in distinguishing those with and without intracranial lesions on CT. The area under the curve for GFAP was significantly higher than for S100β (p<0.013).

Cutoff points for GFAP and S100β were derived from the ROC curves for detecting intracranial lesions on CT scan to maximize the sensitivity and correctly classify all CT positive lesions. Classification performance for detecting intracranial lesions on CT at a GFAP cutoff level of 0.15 ng/mL yielded a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 60-100), a specificity of 36% (95% CI 26-47), and a likelihood ratio 1.6 (95% CI 1.3-1.8; Table 2A). Classification performance for detecting intracranial lesions on CT at a S100β cutoff level of 0.020 ng/mL yielded a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 60-100), a specificity of 26% (95% CI 5-22), and a likelihood ratio 1.4 (95% CI 1.2-1.5; Table 2B).

Table 2.

Contingency Table and Classification Performance of Serum GFAP and S100β in Detecting Intracranial Lesions on CT

| A. Classification Performance of Serum GFAP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT positive | CT negative | Sensitivity | 100% (60-100) | |

|

GFAP positive >0.15 ng/mL |

8 | 54 | Specificity | 36% (26-47) |

|

GFAP negative ≤0.15 ng/mL |

0 | 30 | NPV | 100% (86-100) |

| PPV | 13% (6-24) | |||

| B. Classification Performance of Serum S100β | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT positive | CT negative | Sensitivity | 100% (60-100) | |

|

S100β positive ≥0.02 ng/mL |

8 | 62 | Specificity | 26% (17-37) |

|

S100β negative <0.02 ng/mL |

0 | 22 | NPV | 100% (82-100) |

| PPV | 11% (5-22) | |||

GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; CT, computed tomography; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Discussion

This prospective study compared the performance of GFAP and S100β in head trauma in a cohort of children and youth presenting to two pediatric and one adult Level 1 trauma centers. The use of trauma controls in place of uninjured controls allowed the biomarkers to be assessed in a population that has been exposed to trauma, resembling a typical clinical setting. Further, we elected to include head trauma patients with and without TBI symptoms, as young children cannot always express TBI symptoms. In this young population of primarily mild traumatic brain injury patients with GCS scores of 13-15, GFAP out-performed S100β both in distinguishing head trauma from no head trauma and in detecting traumatic intracranial lesions on head CT. This study is an important addition to the current pediatric biomarker literature and a natural extension of the adult literature that compares and contrasts a novel marker (GFAP) to a more established one (S100β) in the setting of acute trauma.

The superior performance of GFAP over S100β in diagnosing TBI on neuroimaging has been shown in studies of severe TBI in adults.20-22 More importantly, the results of this study are consistent with recent adult studies of GFAP in mild TBI. In 2012, Papa and colleagues examined GFAP in mild TBI adult patients and found that serum GFAP distinguished mild TBI patients from orthopedic controls and motor vehicle crash controls.15 Similarly, Metting and colleagues found that GFAP was increased in patients with an abnormal CT, compared with normal CT acutely after injury, and also noted that GFAP was elevated in patients with axonal injury on magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) at three months post-injury. However, S100β did not perform as well and was not associated with findings on either CT or MRI.16 Accordingly, in 2014, another adult mild TBI study showed how GFAP out-performed S100β in a general trauma population, particularly in those with fractures, appropriately distinguishing extracranial from intracranial lesions.18

Overall, GFAP had a greater AUC for detecting traumatic intracranial lesions on CT scan than S100β (0.85 vs. 0.67). This difference was maintained when younger patients were examined, such as children younger than 10 years old (0.96 vs. 0.72) and children younger than 5 years old (1.00 vs. 0.62). It is very important that brain injury biomarkers accurately classify young children, as they are least able to express themselves and are at highest risk of the ill effects of ionizing radiation.2,3 Taken together, these findings suggest that GFAP has better specificity for brain injury acutely than S100β.

A number of clinical decision rules have been developed to help guide clinical decision making for ordering head CT in children with head trauma: the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network rule,23 Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head Injury,24 and the Children's Head Injury Algorithm for the Prediction of Important Clinical Events.25 These rules have recently been compared in a separate cohort of children with head trauma and have shown considerable variability in their sensitivities and specificities for detecting brain injury.26 Further, some of the rules missed intracranial lesions and performed worse than clinical judgment. The problem with clinical decision rules is that they are inconsistently applied among physicians and their use is subject to interpretation and bias. A blood test for children is more appealing because it is objective and devoid of bias and interpretation. Assuming that reproducible results in rigorous multicenter studies can be attained, some of the barriers foreseen to the implementation of biomarkers such as GFAP in the clinical setting include physician acceptance and preferences, concerns for litigation, and cost.

The authors recognize that there are limitations to our study. This study addressed severity of injury in the acute care setting and did not describe long-term outcome in these patients. Outcome data will be assessed as these data become available in our ongoing studies. All patients presented to two pediatric and one adult Level 1 trauma centers in order to assess their performance in a multiple trauma setting. Since this study was conducted at specialty trauma centers, the generalizability to community settings would have to be further examined. However, the demographics of the trauma patients included here is comparable to academic medical centers across the country. Although the sample size is considerably larger than many pediatric TBI biomarker studies, a larger multicenter sample will be needed to validate these results before clinical use.

Conclusion

In a pediatric trauma population with and without head trauma, GFAP out-performed S100β in detecting head trauma and predicting traumatic intracranial lesions on head CT. This study is among the first published to date to prospectively compare these two biomarkers in children and youth with mild TBI. These results support the brain-specific nature of GFAP, compared with S100β, and the need to study GFAP in a larger sample of children and youth. These findings will require further validation in a larger multicenter sample before clinical application.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported in part by Award Number R01NS057676 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

Linda Papa is a scientific consultant of Banyan Biomarkers, Inc. but receives no stocks or royalties from the company and will not benefit financially from this publication. For the remaining authors, no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Papa L., Ramia M.M., Kelly J.M., Burks S.S., Pawlowicz A., and Berger R.P. (2013). Systematic review of clinical research on biomarkers for pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 30, 324–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner D.J. (2002). Estimating cancer risks from pediatric CT: going from the qualitative to the quantitative. Pediatr. Radiol. 32, 228–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner D.J. and Hall E.J. (2007). Computed tomography–an increasing source of radiation exposure. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2277–2284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger R.P., Pierce M.C., Wisniewski S.R., Adelson P.D., and Kochanek P.M. (2002). Serum S100B concentrations are increased after closed head injury in children: a preliminary study. J. Neurotrauma 19, 1405–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson C.A., Burns J.C., and Peterson B.M. (2010). Low plasma D-dimer concentration predicts the absence of traumatic brain injury in children. J. Trauma 68, 1072–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bechtel K., Frasure S., Marshall C., Dziura J., and Simpson C. (2009). Relationship of serum S100B levels and intracranial injury in children with closed head trauma. Pediatrics 124, e697–e704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellani C., Bimbashi P., Ruttenstock E., Sacherer P., Stojakovic T., and Weinberg A.M. (2009). Neuroprotein s-100B—a useful parameter in paediatric patients with mild traumatic brain injury? Acta Paediatr. 98, 1607–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothoerl R.D. and Woertgen C. (2001). High serum S100B levels for trauma patients without head injuries. Neurosurgery 49, 1490–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romner B. and Ingebrigtsen T. (2001). High serum S100B levels for trauma patients without head injuries. Neurosurgery 49, 1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson R.E., Hansson L.O., Nilsson O., Dijlai-Merzoug R., and Settergen G. (2001). High serum S100B levels for trauma patients without head injuries. Neurosurgery 49, 1272–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelinka L.E., Kroepfl A., Schmidhammer R., Krenn M., Buchinger W., Redl H., and Raabe A. (2004). Glial fibrillary acidic protein in serum after traumatic brain injury and multiple trauma. J. Trauma 57, 1006–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unden J., Bellner J., Eneroth M., Alling C., Ingebrigtsen T., and Romner B. (2005). Raised serum S100B levels after acute bone fractures without cerebral injury. J. Trauma 58, 59–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmer D.B., Cornwall E.H., Landar A., and Song W. (1995). The S100 protein family: history, function, and expression. Brain Res. Bull. 37, 417–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsson B., Zetterberg H., Hampel H., and Blennow K. (2011). Biomarker-based dissection of neurodegenerative diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 520–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papa L., Lewis L.M., Falk J.L., Zhang Z., Silvestri S., Giordano P., Brophy G.M., Demery J.A., Dixit N.K., Ferguson I., Liu M.C., Mo J., Akinyi L., Schmid K., Mondello S., Robertson C.S., Tortella F.C., Hayes R.L., and Wang K.K. (2012). Elevated levels of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein breakdown products in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury are associated with intracranial lesions and neurosurgical intervention. Ann. Emerg. Med. 59, 471–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metting Z., Wilczak N., Rodiger L.A., Schaaf J.M., and van der Naalt J. (2012). GFAP and S100B in the acute phase of mild traumatic brain injury. Neurology 78, 1428–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz-Arrastia R., Wang K.K., Papa L., Sorani M.D., Yue J.K., Puccio A.M., McMahon P.J., Inoue T., Yuh E.L, Lingsma H.F., Maas A.I., Valadka A.B., Okonkwo D.O., Manley G.T., Casey I.S., Cheong M., Cooper S.R., Dams-O'Connor K., Gordon W.A., Hricik A.J., Menon D.K., Mukherjee P., Schnyer D.M., Sinha T.K., and Vassar M.J. (2014). Acute biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: relationship between plasma levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. J. Neurotrauma 31, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papa L., Silvestri S., Brophy G.M., Giordano P., Falk J.L., Braga C.F., Tan C.N., Ameli N.J., Demery J.A., Dixit N.K., Mendes M.E., Hayes R.L., Wang K.K., and Robertson C.S. (2014). GFAP out-performs S100beta in detecting traumatic intracranial lesions on computed tomography in trauma patients with mild traumatic brain injury and those with extracranial lesions. J. Neurotrauma 31, 1815–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eng L.F., Vanderhaeghen J.J., Bignami A., and Gerstl B. (1971). An acidic protein isolated from fibrous astrocytes. Brain Res. 28, 351–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda M., Tsuruta R., Kaneko T., Kasaoka S., Yagi T., Todani M., Fujita M., Izumi T., and Maekawa T. (2010). Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein is a highly specific biomarker for traumatic brain injury in humans compared with S-100B and neuron-specific enolase. J. Trauma 69, 104–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelinka L.E., Kroepfl A., Leixnering M., Buchinger W., Raabe A., and Redl H. (2004). GFAP versus S100B in serum after traumatic brain injury: relationship to brain damage and outcome. J. Neurotrauma 21, 1553–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vajtr D., Benada O., Linzer P., Samal F., Springer D., Strejc P., Beran M., Prusa R., and Zima T. (2013). Immunohistochemistry and serum values of S-100B, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and hyperphosphorylated neurofilaments in brain injuries. Soud Lek. 57, 7–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuppermann N., Holmes J.F., Dayan P.S., Hoyle J.D., Jr., Atabaki S.M., Holubkov R., Nadel F.M., Monroe D., Stanley R.M., Borgialli D.A., Badawy M.K., Schunk J.E., Quayle K.S., Mahajan P., Lichenstein R., Lillis K.A., Tunik M.G., Jacobs E.S., Callahan J.M., Gorelick M.H., Glass T.F., Lee L.K., Bachman M.C., Cooper A., Powell E.C., Gerardi M.J., Melville K.A., Muizelaar J.P., Wisner D.H., Zuspan S.J., Dean J.M., and Wootton-Gorges S.L. (2009). Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 374, 1160–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osmond M.H., Klassen T.P., Wells G.A., Correll R., Jarvis A., Joubert G., Bailey B., Chauvin-Kimoff L., Pusic M., McConnell D., Nijssen-Jordan C., Silver N., Taylor B., and Stiell I.G. (2010). CATCH: a clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury. CMAJ 182, 341–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunning J., Daly J.P., Lomas J.P., Lecky F., Batchelor J., and Mackway-Jones K. (2006). Derivation of the children's head injury algorithm for the prediction of important clinical events decision rule for head injury in children. Arch. Dis. Child 91, 885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Easter J.S., Bakes K., Dhaliwal J., Miller M., Caruso E., and Haukoos J.S. (2014). Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE rules for children with minor head injury: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 64, 145–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]