Abstract

Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is an inflammatory and angiogenic disease. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has an important effect on the pathological progression of CSDH. The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and VEGF also play a significant role in pathological angiogenesis. Our research was to investigate the level of MMPs and VEGF in serum and hematoma fluid. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) shows the characteristics of different stages of CSDH. We also analyzed the relationship between the level of VEGF in subdural hematoma fluid and the appearances of the patients' MRI. We performed a study comparing serum and hematoma fluid in 37 consecutive patients with primary CSDHs using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity was assayed by the gelatin zymography method. The patients were divided into five groups according to the appearance of the hematomas on MRI: group 1 (T1-weighted low, T2-weighted low, n=4), group 2 (T1-weighted high, T2-weighted low, n=11), group 3 (T1-weighted mixed, T2-weighted mixed, n=9), group 4 (T1-weighted high, T2-weighted high, n=5), and group 5 (T1-weighted low, T2-weighted high, n=8). Neurological status was assessed by Markwalder score on admission and at follow-up. The mean age, sex, and Markwalder score were not significantly different among groups. The mean concentration of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 were significantly higher in hematoma fluid than in serum (p<0.01). The level of pro-MMP-2 was higher in hematoma fluid (p<0.01). Measurement of MMP-9 showed both pro and active forms in both groups, but levels were higher in hematoma fluid (p<0.01 and p<0.01, respectively). Mean VEGF concentration was highest in group 1 (21,979.3±1387.3 pg/mL), followed by group 2 (20,060.1±1677.2 pg/mL), group 3 (13,746.5±3529.7 pg/mL), group 4 (7523.2±764.9 pg/mL), and lowest in group 5 (6801.9±618.7 pg/mL). There was a significant correlation between VEGF concentrations and MRI type (r=0.854). The present investigation is the first report showing that the concentrations of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are significantly elevated in hematoma fluid, suggesting that the MMPs/VEGF system may be involved in the angiogenesis of CSDH. We also demonstrate a significant correlation between the concentrations of VEGF and MRI appearance. This finding supports the hypothesis that high VEGF concentration in the hematoma fluid is of major pathophysiological importance in the generation and steady increase of the hematoma volume, as well as the determination of MRI appearance.

Key words: : CSDH, MMP-2, MMP-9, MRI, VEGF

Introduction

Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is a post-traumatic disease frequently treated by neurosurgery.1 However, the formation and enlargement mechanism of CSDH still remains inconclusive. It is generally thought that CSDH is an inflammatory and angiogenic disease, Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in angiogenesis, and in CSDH patients its concentration in the subdural hematoma fluid is higher than its concentration in serum.2,3 Additionally, several studies have found the pathway of VEGF to be active in CSDH patients.4–7 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and VEGF also play a significant role in normal and pathological angiogenesis.8,9 Until now, the levels of MMPs in hematoma fluid and serum from patients with CSDH have not been studied. In the present study, we measured the concentration of MMP-2, MMP-9, and VEGF in the serum and hematoma fluid using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We also examined the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the two groups by gelatin zymography. Weigel and coworkers reported that CT scan appearances of CSDHs related to the concentration of VEGF in the hematoma cavity. MRI has an advantage over CT scan with respect to the quality of the image.10 Therefore, MRI could better predict the progression and recurrence of CSDH than CT scan.11,12 In our study, we investigated the relationship between the concentration of VEGF in hematoma fluid and MRI type.

Methods

Patients

The study included 42 consecutive patients who were treated for CSDH by surgery at the First Hospital of Jilin University between March 2013 and April 2014. Five patients were excluded because of long-term use of thrombolytics or anticoagulant drugs (n=3), or hepatic and hematological disease (n=2). There were 25 males and 12 females ranging in age from 45 to 83 years (mean age 61.4±9.7 years). All of the patients had a history of brain injury diagnosed >21 days after the initial injury. All patients required operation based on the appearance of CSDH proved by CT and MRI. All patients received single burr-hole irrigation under general anesthesia. Serum samples were drawn preoperatively into a serum separator tube (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, USA) and allowed to stand for 30 min at room temperature to ensure full clotting. Hematoma fluid was collected into the vacuum tube after opening of the outer hematoma membrane. All samples were centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min and supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until assayed. Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all participants or their guardians. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The First Hospital of Jilin University (IRB00008484).

Measurements of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 by ELISA

We measured the concentration of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in hematoma fluid and serum using commercially available solid phase ELISA kits (R&D Systems Inc, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were performed in duplicates. The experimenter was blinded to the patients' clinical data.

Measurements of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity by gelatin zymography

A zymography technique with the use of NOVEX 10% zymogram (Gelatin) Protein Gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was employed.13 For each sample, 300 μg of total protein was applied to the gel and submitted to electrophoresis in Tris/glycine/sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) running buffer at a constant current of 15 mA. After electrophoresis, the gel was submitted to extraction of SDS with 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, at 37°C for 30 min. After extraction, the gel was transferred into 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.02% NaN3, and 1% Triton X-100, and incubated at 37°C for 72 h. The protease bands appeared as clear bands on a blue background. MMP-2 and MMP-9 standards were run concurrently for determining the molecular weight of MMP bands. Samples all were analyzed in duplicate. Gels were scanned and quantification of the bands was determined using ImageJ software version 1.48 (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean±SD. The paired t test was applied to assess possible differences in the levels of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 between hematoma fluid and serum. Nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was assessed to examine the differences of VEGF mean concentrations among the MRI type groups. Correlations among the various measured parameters were calculated by Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. For all statistical tests, the level of significance was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software version 17.0.0 (SPSS, IBM Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

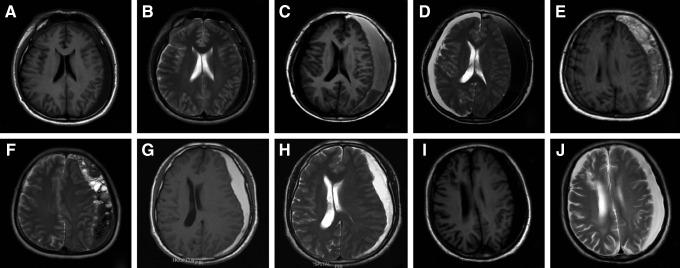

Epidemiological and clinical data of the patients included are shown in Table 1. MRI scans were analyzed and categorized into the five groups by radiologists blinded to the VEGF levels: group 1 (T1-weighted low, T2-weighted low, n=4), group 2 (T1-weighted high, T2-weighted low, n=11), group 3 (T1-weighted mixed, T2-weighted mixed, n=9), group 4 (T1-weighted high, T2-weighted high, (n=5), and group 5 (T1-weighted low, T2-weighted high, n=8) (Fig. 1). There was a predominance of males, with a sex ratio of 2.2/1. The mean age, sex ratio, and Markwalder scores were not significantly different among groups.

Table 1.

MRI Classification and Clinical Features

| Clinical Data | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | 4 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 8 | >0.05 |

| Age (yrs) | 67.3±4.8 | 64.7±10.5 | 69.9±8.1 | 63.6±10.7 | 62.4±8.7 | >0.05 |

| Gender (F/M) | 1/4 | 4/7 | 2/7 | 2/3 | 3/5 | >0.05 |

| Pre Markwalder score | 1.7±0.2 | 1.6±0.3 | 1.6±0.2 | 1.7±0.1 | 1.6±0.2 | >0.05 |

| Post Markwalder score | 0.7±0.2 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.7±0.3 | >0.05 |

| MRI T1-weighted | Low | High | Mixed | High | Low | |

| MRI T2-weighted | Low | Low | Mixed | High | High |

p<0.05.

Pre, preoperation; Post, postoperation.

FIG. 1.

Classification of hematomas by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI scans were categorized into the five groups. Group 1 (A) T1-weighted low, (B) T2-weighted low; group 2 (C) T1-weighted high, (D) T2-weighted low; group 3 (E) T1-weighted mixed, (F) T2-weighted mixed; group 4 (G) T1-weighted high, (H) T2-weighted high; group 5 (I) T1-weighted low, (J) T2-weighted high.

ELISA analysis of VEGF, MMP-2 and MMP-9

The mean concentrations of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in hematoma fluid and serum acquired in the patients are shown in Table 2. Levels of all factors were significantly higher in hematoma fluid than in serum (p<0.01). Spearman's correlation analysis showed that concentrations of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were correlated with the concentrations of VEGF in hematoma fluid (MMP-2, r=0.833, p<0.01; MMP-9, r=0.879, p<0.01).

Table 2.

Concentration of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in Serum and Hematoma Fluid in 37 Patients with CSDHs

| Factor | VEGF (pg/mL) | MMP-2 (ng/mL) | MMP-9 (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | 339.7±62.5 | 69.4±8.5 | 131.7±7.1 |

| Hematoma fluid | 14,171.1±6282.8* | 2252.2±807.7* | 3074.8±1381.3* |

p<0.01.

VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; CSDH, chronic subdural hematoma.

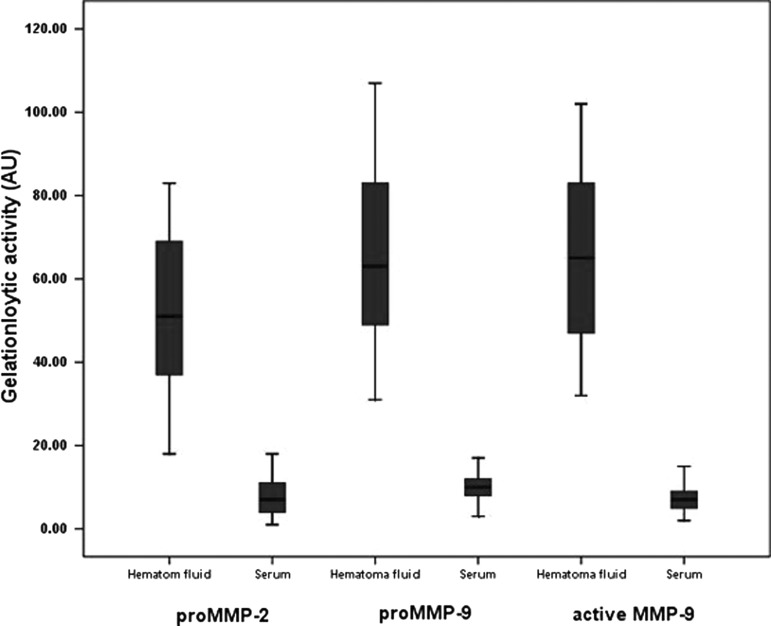

Gelatin zymography analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9

The drawback to measuring MMP-2 and MMP-9 concentrations by ELISA is that it is not possible to distinguish between pro and active MMP-2 and MMP-9. To identify different activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 forms, we performed quantitative zymography. The level of pro-MMP-2 was higher in hematoma fluid (p<0.01). Active MMP-2 was not found in either group. Measurement of MMP-9 showed both pro and active forms in both groups, but levels were higher in hematoma fluid (p<0.01 and p<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2). MMP-9 levels measured by ELISA correlated significantly with active MMP-9 forms identified by the zymography in hematoma fluid (p<0.001).

FIG. 2.

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 activity in hematoma fluid and serum. Horizontal lines represent means (±SD) of the integrated density obtained from the gelatinolytic bands. Values, expressed as arbitary units (AU), were significantly different between hematoma fluid and serum in the chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) patients (p<0.01).

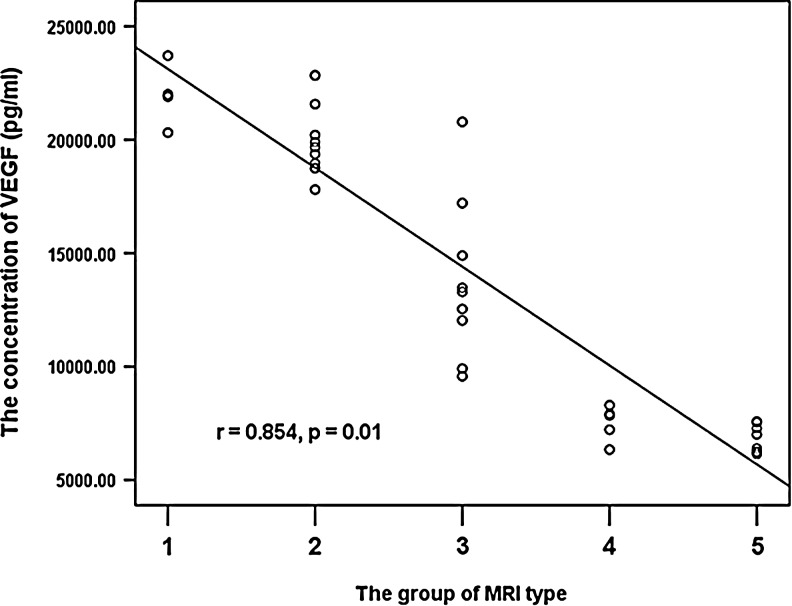

Concentration of VEGF in the different MRI groups

The average concentration of VEGF was highest in group 1 (21,979.3±1387.3 pg/mL). The group 2 and group 3 patients had a comparably high level of VEGF in hematoma fluid. The concentration of VEGF was markedly lower group 4 and was lowest in group 5 (7523.2±764.9 pg/mL and 6801.9±618.7 pg/mL; Table 3). We then related VEGF concentrations in hematoma fluid of the different MRI classes to the re-bleeding described by Kaminogo and coworkers.11 Respective data for all patients are shown in Figure 3. Re-bleeding and VEGF concentrations proved to be clearly related, yielding significant correlation (r=0.854; p<0.01; Fig. 3).

Table 3.

The Relationship between VEGF Concentration and MRI Type

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF (pg/mL) | 21,979.3±1387.3 | 20,060.1±1677.2 | 13,746.5±3529.7 | 7523.2±764.9 | 6801.9±618.7 |

| Group 2 | |||||

| Group 3 | |||||

| Group 4 | |||||

| Group 5 |

Dark gray box: p<0.05; light gray box: p>0.05.

VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

FIG. 3.

Patients were classified into five groups according to the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of the hematoma. The correlation coefficient for the concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF and MRI-type is highly significant (r=0.854; p<0.01).

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the levels of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in patients with CSDH to investigate the difference between hematoma fluid and serum. The concentrations of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 were markedly higher in hematoma fluid compared with serum in patients. An increased level of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in the hematoma fluid of the patients with CSDH is consistent with a large body of clinical and experimental evidence indicating enhanced expression of these factors under conditions that favor pathological angiogenesis.

The cause and mechanism of enlargement of hematomas remains unclear in CSDH patients. Most studies agreed that the continuous formation of immature, fragile blood vessels, which are prone to hemorrhagic events, contributes to progressive enlargement of the lesions. The formation of new blood vessels is a highly regulated process that depends upon mitogenic and non-mitogenic angiogenic, factors and involves matrix remodeling, cell migration, and regulated adhesive interactions between vascular cells and the matrix. Moreover, unlike normal vessels, blood vessels within the cavity of CSDHs are immature and inflammatory in nature.

VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 play critical roles in the initiation and progression of vascular pathology.14 MMP-2 and MMP-9 are critical pro-angiogenic molecules that trigger15 the “angiogenic switch” in the quiescent vasculature.16 MMP-9 have been shown to be crucial for the development of the tumor angiogenic vasculature in models of pancreatic, ovarian and skin cancer.17–19 MMP-2 also shows a significant role in normal and tumor angiogenesis.20,21 They mobilize the recruitment of bone marrow-derived angiogenic precursors to the tumor stroma, enhancing the tumor angiogenic and vasculargenic process.8,22 MMP-9 also triggers the “angiogenic switch” facilitated by the release of TIMP-1-free gelatinase MMP-9 from neutrophils, which acts as an exceptionally potent nanomolar angiogenic factor, releasing both fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and VEGF from matrices.23 MMP-9 recruits bone marrow-derived leukocytes and support cells to tumor vessels, regulating vessel maturation in human neuroblastomas.24 The MMP-9/VEGF system has also been implicated in the robust angiogenic response associated with TrkAIII oncogene promotion of neuroblastoma tumorigenicity.9

Several studies have found that MMPs and VEGF were increased in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), but were significantly decreased over time.25–27 Our patients were seen >21 days after injury; therefore, the impact of elevations in MMPs/VEGF occurring in TBI patients on the research is limited. Several studies have reported that the concentration of VEGF was higher in hematoma fluid than in serum in CSDH patients.4,28–31 However, concentrations of MMPs in hematoma fluid and serum from patients with CSDH have not been reported until now. Our study showed that in patients with CSDH, the levels of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 are significantly higher in hematoma fluid than in serum by ELISA. However, because the ELISA measured both the pro and the active forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9, these observations have only a limited value. Therefore, MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity was tested by gelatin zymography. The level of pro-MMP-2 was higher in hematoma fluid than serum (p<0.01). Active MMP-2 was not found in either group. It is known that MMP-2 lacks a promoter sequence, which is linked with its constitutive expression and its less prominent responsiveness to most stimuli.32 MMP-9 activity was higher in hematoma fluid than serum (p<0.01). A higher MMP-9 activation could be the result of a higher MMP-9 expression. MMP-9 levels measured by ELISA correlated significantly with active MMP-9 form identified by gelatin zymography in hematoma fluid (p<0.001). Moreover, the significant correlation was found between the concentration of VEGF in hematoma fluid and either MMP-2 concentration or MMP-9 concentration. This supports the body of evidence that shows the MMPs/VEGF system playing an important role in the formation of pathological blood vessels. Recently, Zhang and coworkers reported that atorvastatin, a VEGF inhibitor, is effective in reducing CSDH by promoting membrane neovascularization, which facilitates blood drainage and reduces inflammation in CSDH.33 Given our finding regarding the levels of MMPs in hematoma fluid, using MMP inhibitors as a possible treatment for CSDH patients could be an important area of future research.

VEGF is known to play an important role in the initiation and progression of vascular pathology. Weigel and coworkers first reported a pathophysiological link between VEGF concentration and the exudation rate underlying the steady increase of hematoma volume and CT appearance.10 Considering the advantages of MRI over CT scanning in the evaluation of CSDHs, especially in cases of isodense CSDHs,34 we wanted to investigate the relationship between VEGF levels and MRI type in CSDH patients. MRI can reveal low signal on T2-weighted in CSDH with fresh re-bleeding. Imaizumi and coworkers found that T2-weighted MRI images are important for predicting the enlargement and recurrence of a CSDH.35 When fresh re-bleeding develops in patients with CSDH, the fresh component is demonstrated as low on a T1-weighted MRI. Tsutsumi and coworkers reported that CSDHs in the high-intensity group may be less prone to recur than those in non-high-intensity group.36

In our research, the level of VEGF was the highest in T1-weighted low and T2-weighted low patients (group 1). These VEGF levels of the T2-weighted low patients (group 2) were significantly higher than in T2-weighted high patients (group 4 and group 5). There were different stages of hematoma in group 3, producing MRI both high and low in density. The concentration of VEGF was moderate in group 3 compared with the other groups. These MRI data correspond to the CT results previously presented by Weigel and coworkers.10

CSDHs are presumed to have a pathological progression extending from a proliferative to a degenerative stage, as shown by histological analysis of the hematoma membrane and periodic follow-up CT scans showing spontaneously resolving CSDHs.37 The driving factor in the early proliferative stage seems to be repeated microhemorrhaging from microvessels of the neomembrane. In this stage, microvessels of the neomembrane may be more vulnerable, and more susceptible to re-bleeding. If fresh re-bleeding develops, this fresh component is demonstrated as “low” on a T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI. During the late proliferative stage, exudation from macrocapillaries in the outer membrane of CSDHs may play an important role in the lesion's enlargement when the hematoma membrane is more mature and less likely to re-bleed.38 The present data support the idea that CSDHs categorized as high intensity on T2-weighted images might enlarge by exudation mechanism. Our findings align with the previous work by Weigel and coworkers, who reported a pathophysiological link between the VEGF concentration and the exudation rate underlying the steady increase of hematoma volume and CT appearance.10

Conclusion

In summary, the present investigation characterizes the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in CSDH patients. These novel findings demonstrate that the concentrations of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are significantly elevated in hematoma fluid over serum, suggesting that the MMPs/VEGF system may be involved in the angiogenesis of CSDH. Further studies using inhibitors of the signaling pathway may help to treat CSDH.

Additionally, the current data shows a significant correlation between concentrations of VEGF and the different classes of MRI appearance. This suggests that the high VEGF concentration in the hematoma fluid is of major pathophysiological importance, in the generation and steady increase of the hematoma volume, and in determining the MRI appearance. The pathogenic mechanisms involved in hematoma enlargement are repeated bleeding caused by ongoing pathological angiogenesis, and exudation of plasma components resulting from high vessel permeability.

Acknowledgments

This work was worked supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81201980) and Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province, China (No. 20130522028JH).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Cenic A., Bhandari M., and Reddy K. (2005). Management of chronic subdural hematoma: a national survey and literature review. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 32, 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weigel R., Schilling L., and Schmiedek P. (2001). Specific pattern of growth factor distribution in chronic subdural hematoma (CSH): evidence for an angiogenic disease. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 143, 811–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hohenstein A., Erber R., Schilling L., and Weigel R. (2005). Increased mRNA expression of VEGF within the hematoma and imbalance of angiopoietin-1 and -2 mRNA within the neomembranes of chronic subdural hematoma. J. Neurotrauma 22, 518–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanko N., Tanikawa M., Mase M., Fujita M., Tateyama H., Miyati T., and Yamada K. (2009). Involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor in the mechanism of development of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurol. Med. Chir (Tokyo) 49, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funai M., Osuka K., Usuda N., Atsuzawa K., Inukai T., Yasuda M., Watanabe Y., and Takayasu M. Activation of PI3 kinase/Akt signaling in chronic subdural hematoma outer membranes. J. Neurotrauma 28, 1127–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osuka K., Watanabe Y., Usuda N., Atsuzawa K., Aoyama M., Niwa A., Nakura T., and Takayasu M. Activation of Ras/MEK/ERK signaling in chronic subdural hematoma outer membranes. Brain Res. 1489, 98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osuka K., Watanabe Y., Usuda N., Aoyama M., Takeuchi M., and Takayasu M. (2014). Eotaxin-3 activates Smad through the TGF-beta1 pathway in chronic subdural hematoma outer membranes. J. Neurotrauma 31, 1451–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao D., Nolan D., McDonnell K., Vahdat L., Benezra R., Altorki N., and Mittal V. (2009). Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells contribute to the angiogenic switch in tumor growth and metastatic progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1796, 33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tacconelli A., Farina A.R., Cappabianca L., Desantis G., Tessitore A., Vetuschi A., Sferra R., Rucci N., Argenti B., Screpanti I., Gulino A., and Mackay A.R. (2004). TrkA alternative splicing: a regulated tumor-promoting switch in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell 6, 347–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weigel R., Hohenstein A., and Schilling L. Vascular endothelial growth factor concentration in chronic subdural hematoma fluid is related to computed tomography appearance and exudation rate. J. Neurotrauma 31, 670–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminogo M., Moroki J., Ochi A., Ichikura A., Onizuka M., Shibayama A., Miyake H., and Shibata S. (1999). Characteristics of symptomatic chronic subdural haematomas on high-field MRI. Neuroradiology 41, 109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurokawa Y., Ishizaki E., and Inaba K. (2005). Bilateral chronic subdural hematoma cases showing rapid and progressive aggravation. Surg. Neurol. 64, 444–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng Z.S., Shu W.P., Cohen A.M., and Guillem J.G. (2002). Matrix metalloproteinase-7 expression in colorectal cancer liver metastases: evidence for involvement of MMP-7 activation in human cancer metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 144–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmeliet P., and Jain R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473, 298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hinsbergh V.W., Engelse M.A. and Quax P.H. (2006). Pericellular proteases in angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 716–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergers G., and Benjamin L.E. (2003). Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang S., Van Arsdall M., Tedjarati S., McCarty M., Wu W., Langley R., and Fidler I.J. (2002). Contributions of stromal metalloproteinase-9 to angiogenesis and growth of human ovarian carcinoma in mice. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94, 1134–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergers G., Brekken R., McMahon G., Vu T.H., Itoh T., Tamaki K., Tanzawa K., Thorpe P., Itohara S., Werb Z., and Hanahan D. (2000). Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 737–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coussens L.M., Tinkle C.L., Hanahan D., and Werb Z. (2000). MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell 103, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burbridge M.F., Coge F., Galizzi J.P., Boutin J.A., West D.C., and Tucker G.C. (2002). The role of the matrix metalloproteinases during in vitro vessel formation. Angiogenesis 5, 215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh T., Tanioka M., Yoshida H., Yoshioka T., Nishimoto H., and Itohara S. (1998). Reduced angiogenesis and tumor progression in gelatinase A-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 58, 1048–1051 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng X.W., Kuzuya M., Nakamura K., Maeda K., Tsuzuki M., Kim W., Sasaki T., Liu Z., Inoue N., Kondo T., Jin H., Numaguchi Y., Okumura K., Yokota M., Iguchi A., and Murohara T. (2007). Mechanisms underlying the impairment of ischemia-induced neovascularization in matrix metalloproteinase 2-deficient mice. Circ. Res. 100, 904–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ardi V.C., Van den Steen P.E., Opdenakker G., Schweighofer B., Deryugina E.I., and Quigley J.P. (2009). Neutrophil MMP-9 proenzyme, unencumbered by TIMP-1, undergoes efficient activation in vivo and catalytically induces angiogenesis via a basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2)/FGFR-2 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25,854–25,866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jodele S., Chantrain C.F., Blavier L., Lutzko C., Crooks G.M., Shimada H., Coussens L.M., and Declerck Y.A. (2005). The contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to the tumor vasculature in neuroblastoma is matrix metalloproteinase-9 dependent. Cancer Res. 65, 3200–3208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts D.J., Jenne C.N., Leger C., Kramer A.H., Gallagher C.N., Todd S., Parney I.F., Doig C.J., Yong V.W., Kubes P., and Zygun D.A. A prospective evaluation of the temporal matrix metalloproteinase response after severe traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurotrauma 30, 1717–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong D., Hao M., Liu L., Liu C., Dong J., Cui Z., Sun L., Su S., and Zhang J. Prognostic relevance of circulating endothelial progenitor cells for severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 26, 291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu C.L., Chen C.C., Lee H.C., and Cho D.Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the ventricular cerebrospinal fluid correlated with the prognosis of traumatic brain injury. Turk. Neurosurg. 24, 363–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki K., Takano S., Nose T., Doi M., and Ohashi N. (1999). Increased concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in chronic subdural hematoma. J. Trauma 46, 532–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shono T., Inamura T., Morioka T., Matsumoto K., Suzuki S.O., Ikezaki K., Iwaki T., and Fukui M. (2001). Vascular endothelial growth factor in chronic subdural haematomas. J. Clin. Neurosci. 8, 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hara M., Tamaki M., Aoyagi M., and Ohno K. (2009). Possible role of cyclooxygenase-2 in developing chronic subdural hematoma. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 56, 101–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong H.J., Kim Y.J., Yi H.J., Ko Y., Oh S.J., and Kim J.M. (2009). Role of angiogenic growth factors and inflammatory cytokine on recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma. Surg. Neurol. 71, 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manicone A.M., and McGuire J.K. (2008). Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19, 34–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D., Li T., Tian Y., Wang S., Jin C., Wei H., Quan W., Wang J., Chen J., Dong J., Jiang R., and Zhang J. Effects of atorvastatin on chronic subdural hematoma: a preliminary report from three medical centers. J. Neurol. Sci. 336, 237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosoda K., Tamaki N., Masumura M., Matsumoto S., and Maeda F. (1987). Magnetic resonance images of chronic subdural hematomas. J. Neurosurg. 67, 677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imaizumi T., Horita Y., Honma T., and Niwa J. (2003). Association between a black band on the inner membrane of a chronic subdural hematoma on T2*-weighted magnetic resonance images and enlargement of the hematoma. J. Neurosurg. 99, 824–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsutsumi K., Maeda K., Iijima A., Usui M., Okada Y., and Kirino T. (1997). The relationship of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging findings and closed system drainage in the recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma. J. Neurosurg. 87, 870–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parlato C., Guarracino A., and Moraci A. (2000). Spontaneous resolution of chronic subdural hematoma. Surg Neurol 53, 312–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokmak M., Iplikcioglu A.C., Bek S., Gokduman C.A., and Erdal M. (2007). The role of exudation in chronic subdural hematomas. J. Neurosurg. 107, 290–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]