Abstract

Trypanosoma rangeli is a nonpathogenic parasite for humans; however, its medical importance relies in its similarity and overlapping distribution with Trypanosoma cruzi, causal agent of Chagas disease in the Americas. The genetic diversity of T. rangeli and its association with host species (triatomines and mammals) has been identified along Central and the South America; however, it has not included data of isolates from Ecuador. This study reports infection with T. rangeli in 18 genera of mammal hosts and five species of triatomines in three environments (domestic, peridomestic, and sylvatic). Higher infection rates were found in the sylvatic environment, in close association with Rhodnius ecuadoriensis. The results of this study extend the range of hosts infected with this parasite and the geographic range of the T. rangeli genotype KP1(−)/lineage C in South America. It was not possible to detect variation on T. rangeli from the central coastal region and southern Ecuador with the analysis of the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU-rRNA) gene, even though these areas are ecologically different and a phenotypic subdivision of R. ecuadoriensis has been found. R. ecuadoriensis is considered one of the most important vectors for Chagas disease transmission in Ecuador due to its wide distribution and adaptability to diverse environments. An extensive knowledge of the trypanosomes circulating in this species of triatomine, and associated mammal hosts, is important for delineating transmission dynamics and preventive measures in the endemic areas of Ecuador and Northern Peru.

Key Words: : Trypanosoma rangeli characterization, Rhodnius ecuadoriensis, KP1(−), Lineage C, SSU-rRNA, Loja Province, Manabí Province, Ecuador

Introduction

The parasite Trypanosoma rangeli has been reported as being distributed extensively in Central and South America (Vallejo et al. 2009). Although it is considered nonpathogenic for humans, its medical relevance is related to its morphological and genetic similarity with Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease. T. rangeli is a member of the T. cruzi clade, a group of ≈18 species of trypanosomes that includes T. cruzi and its closest relatives (Cottontail et al. 2014). Moreover, both T. cruzi and T. rangeli overlap their geographic distribution and share the same invertebrate (triatomines) and vertebrate (mammals) hosts. Mixed infection with both parasites has been reported (Vallejo et al. 1988, Pinto et al. 2006, Grijalva et al. 2011, 2012, Villacis et al. 2015). Chagas disease is listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the Neglected Topical Diseases that requires intensified research for integrated measures to improve health and social well-being of the affected populations (World Health Organization 2010). Within this scope, it is necessary to understand the host associations and genetic variation of T. rangeli, a parasite that could be misidentified as T. cruzi, resulting in confounding the diagnosis of Chagas disease (Guhl et al. 1985, Saldana et al. 2005, de Sousa et al. 2008).

T. rangeli is mainly transmitted by salivary inoculation, although oral transmission by ingestion of triatomines has also been proposed as an important epidemiological route of infection with trypanosomes (T. rangeli and T. cruzi) of mammalian hosts such as dogs (Montenegro et al. 2002, Pineda et al. 2011) and other mammals with grooming behavior. Distribution of T. rangeli is related to the distribution of the triatomines; however, it depends on the capacity of triatomines to harbor the infective stage of the parasite in the salivary glands (Guhl and Vallejo 2003). Most species of triatomines can transmit T. cruzi, but the transmission of T. rangeli has been more restricted to the triatomines of the genus Rhodnius (D'Alessandro and de Hincapie 1986, Vallejo et al. 2009). Experimental infection has been conducted in Triatoma, Panstrongylus, and Rhodnius, but only Rhodnius has demonstrated the presence of the infective forms of T. rangeli in the salivary glands (De Stefani Marquez et al. 2006). Natural or experimental infection has been demonstrated in 12 out of the 15 species of Rhodnius (Guhl and Vallejo 2003), although natural infection of the salivary glands has also been reported in the genus Triatoma (Marinkelle 1968).

Biochemical, immunological, and molecular characteristics have identified polymorphisms in T. rangeli strains isolated from different hosts (Grisard et al. 1999). However, the close association with the genus Rhodnius has defined the distribution of the different genotypes (Machado et al. 2001, Urrea et al. 2011). Two main groups (KP1[+] and KP1[−]) have been defined based on the presence/absence of the KP1 minicircle in the kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) (Vallejo et al. 2002). Additionally, analysis of the small subunit of ribosomal RNA (SSU-rRNA) has also identified the presence of five lineages (A, B, C, D, and E) in Central and South America (Maia Da Silva et al. 2007, 2009). Further analysis of the splice leader intergenic region (SL) confirmed that the different genotypes of T. rangeli circulate in association with vectors of the same evolutionary line, independently of the geographic distance (Urrea et al. 2011). Most recently, subdivision in KP1(−) has been detected by microsatellite typing (Sincero et al. 2015). Moreover, with the publication of the genome of T. rangeli (Stoco et al. 2014), the complexity of this parasite could be further addressed.

Multiple studies have evaluated the genetic diversity of T. rangeli along Central and South America. However, none of those have included samples from Ecuador. Even though the presence of T. rangeli has been reported previously in triatomines and mammals from central coastal and southern Ecuador (Pinto et al. 2006, Grijalva et al. 2011, 2012, Villacis et al. 2015), a detailed picture of its distribution and prevalence in these areas has not been assessed. The aim of this study was to contribute information about the diversity of the T. rangeli populations that are circulating in mammals and triatomines in the southern province of Loja and the central coastal province of Manabí, both considered as endemic areas for Chagas disease (Black et al. 2007, 2009).

Materials and Methods

This study was carried out with DNA samples previously collected as part of the Chagas disease projects of the Center for Infectious and Chronic Disease Research (CIDCR) from 2004 to 2012. Samples of this study were collected in 50 rural communities (19 counties) from central coastal Ecuador (Manabí Province) and 53 rural communities (11 counties) from southern Ecuador (Loja Province) (Table 1). DNA was obtained from intestinal contents (Grijalva et al. 2012) of triatomines and blood samples from mammals (Pinto et al. 2006). An aliquot of each sample was inoculated in culture for in vitro trypanosomes isolation (Chiari et al. 1989, Yeo et al. 2007), and DNA was isolated from cultures that presented growth of parasites. All samples were obtained in strict accordance with the protocol approved by the Ohio University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Table 1.

Infection Rates with Trypanosoma rangeli of Mammal Host Species from Three Orders (Chiroptera, Didelphimorphia, and Rodentia) and Triatomines Vectors in Loja Province (Southern Ecuador) and Manabí Province (Central Coastal Ecuador) 2004–2012

| Domicile | Peridomicile | Sylvatic | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region/host/species | No. samples | T. rangeli (%) | No. samples | T. rangeli (%) | No. samples | T. rangeli (%) | No. samples | T. rangeli (%) |

| Southern Ecuador (Loja) | 668 | 12 (2) | 882 | 42 (5) | 584 | 92 (16) | 2134 | 146 (7) |

| Chiropteraa | — | — | — | — | 49 | 1 (2) | 49 | 1 (2) |

| Didelphimorphiab | 1 | 0 (0) | 57 | 0 (0) | 85 | 6 (7) | 143 | 6 (4) |

| Rodentiac | 139 | 0 (0) | 37 | 0 (0) | 90 | 17 (19) | 266 | 17 (6) |

| Triatomine | 528 | 12 (2) | 788 | 42 (5) | 360 | 68 (19) | 1676 | 122 (7) |

| Panstrongylus chinai | 149 | 5 (3) | 33 | 2 (6) | — | — | 182 | 7 (4) |

| Panstrongylus rufotuberculatus | 12 | 0 (0) | — | — | — | — | 12 | 0 (0) |

| Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | 167 | 5 (3) | 617 | 39 (6) | 360 | 68 (19) | 1144 | 112 (10) |

| Triatoma carrioni | 200 | 2 (1) | 138 | 1 (1) | — | — | 338 | 3 (1) |

| Western Ecuador (Manabí) | 106 | 3 (3) | 591 | 66 (11) | 775 | 136 (18) | 1472 | 205 (14) |

| Didelphimorphiad | — | — | 35 | 1 (3) | 12 | 0 (0) | 47 | 1 (2) |

| Rodentiae | 43 | 0 (0) | 31 | 0 (0) | 29 | 0 (0) | 103 | 0 (0) |

| Triatomine | 63 | 3 (5) | 525 | 65 (12) | 734 | 136 (19) | 1322 | 204 (15) |

| Panstrongylus howardi | 7 | 0 (0) | 74 | 4 (5) | 1 | 0 (0) | 82 | 4 (5) |

| Panstrongylus rufotuberculatus | 18 | 0 (0) | 17 | 2 (12) | 14 | 0 (0) | 49 | 2 (4) |

| Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | 38 | 3 (8) | 434 | 59 (14) | 719 | 136 (19) | 1191 | 198 (17) |

| Total | 774 | 15 (2) | 1473 | 108 (7) | 1359 | 228 (17) | 3606 | 351 (10) |

Includes species from the genera Artibeus, Desmodus, and Glossophaga.

Includes species from the genera Didelphis, Marmosa, and Micoureus.

Includes species from the genera Aegialomys, Akodon, Cavia, Mus, Rattus, Rhipidomys, and Sciurus.

Includes species from the genera Didelphis, Marmosa, and Philander.

Includes species from the genera Handleyomys, Hoplomys, Mus, Proechimys, Rattus, Rhipidomys, Sciurus, and Transandinomys.

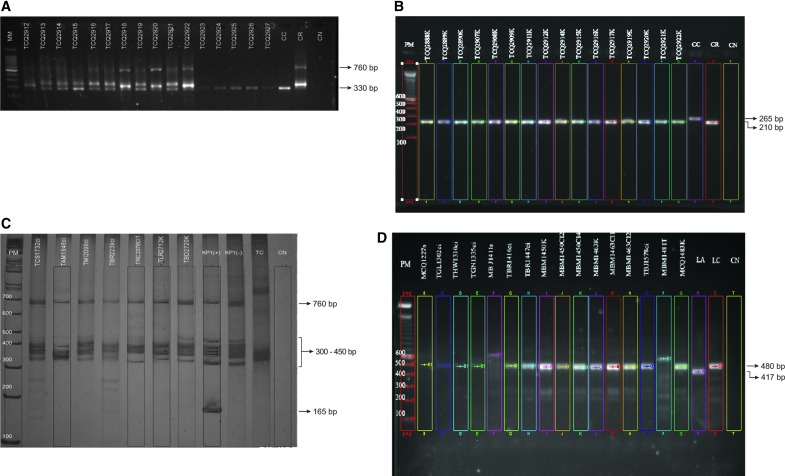

Differential PCR for T. rangeli identification

Initial screening for detection of natural infection with T. rangeli was carried out on 3606 DNA samples obtained from the intestinal contents of triatomines and blood from mammals (Table 1). Samples were amplified for the conserved domain of the minicircle of kDNA, as previously described by Vallejo et al. (1999) for the samples from 2004–2010 and Virreira et al. (2006) for the samples from 2011–2012. Differential detection between T. cruzi and T. rangeli was determined based on the size of the PCR products. A band of 330 bp was expected for T. cruzi, whereas a band of 760 bp together with bands of 300–450 bp defined T. rangeli. Confirmation of T. rangeli infection was carried out with further amplification of the D7a divergent region of the large subunit rRNA gene, as previously described (Souto et al. 1999). A band of 210 bp was expected for T. rangeli, whereas T. cruzi presented a band of 265 bp. A negative control (without DNA) and control DNA for T. cruzi and T. rangeli were used to validate the gels. Bands were detected in a 2% agarose gel.

Selection of T. rangeli samples for genotyping

Genotyping was carried out in a subset of 111 samples. From them, 68 were genotyped from the DNA obtained from intestinal contents/blood samples and 43 from DNA obtained from T. rangeli isolates in culture. This subset is representative of the geographic origin of the samples and includes a diversity of hosts (seven species of triatomines, and four species of mammals) (Table 2). The geographic area included 12 and 27 rural communities in Loja and Manabí Province, respectively.

Table 2.

Percentage of Trypanosoma rangeli Samples Genotyped As KP1(−)/Lineage C Isolated from Triatomines and Mammalian Hosts in Loja Province (Southern Ecuador) and Manabí Province (Central Coastal Ecuador)

| T. rangeli group | T. rangeli lineage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region/host/species | No. samples analyzed | KP1(−) (%) | N.D. (%) | C (%) | N.D. (%) |

| Southern Ecuador (Loja) | 49 | 48 (98) | 1 (2) | 35 (71) | 14 (29) |

| Mammal | |||||

| Desmodus rotundus | 1 | 1 (100) | — | — | 1 (100) |

| Didelphis marsupialis | 4 | 4 (100) | — | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

| Rhipidomys spp. | 3 | 3 (100) | — | 2 (67) | 1 (33) |

| Sciurus stramineus | 3 | 3 (100) | — | 2 (67) | 1 (33) |

| Triatomine | |||||

| Panstrongylus chinai | 5 | 5 (100) | — | 2 (40) | 3 (60) |

| Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | 31 | 30 (97) | 1 (3) | 24 (77) | 7 (23) |

| Triatoma carrioni | 2 | 2 (100) | — | 2 (100) | — |

| Western Ecuador (Manabí) | 62 | 62 (100) | — | 54 (87) | 8 (13) |

| Mammal | |||||

| Didelphis marsupialis | 1 | 1 (100) | — | — | 1 (100) |

| Triatomine | |||||

| Panstrongylus howardi | 3 | 3 (100) | — | 1 (33) | 2 (67) |

| Panstongylus rufotuberculatus | 1 | 1 (100) | — | 1 (100) | — |

| Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | 57 | 57 (100) | — | 52 (91) | 5 (9) |

| Total | 111 | 110 (99) | 1 (1) | 89 (80) | 22 (20) |

N.D., not determined.

Identification of T. rangeli groups (KP1[+] and KP1[−]) by amplification of the conserved regions of the minicircles of kDNA

The conserved regions of the minicircle of kDNA were amplified with the primers S35 (5′-AAA TAA TGT ACG GGT GGA GAT GCA TGA-3′), S36 (5′-GGG TTC GAT TGG GGT TGG TGT-3′), and KP1L (5′-ATA CAA CAC TCT CTA TAT CAG G-3′), as previously described (Vallejo et al. 2002). A band at 760 bp and fragments between 300 and 450 bp were expected in all samples. KP1(+) was identified by the presence of an additional band at 165 bp, whereas KP1(−) was identified by the absence of this fragment. Additionally, samples that could not be classified by the previous markers were amplified for the specific variable region KP1 using the primers KP1U (5′-GTA GAA AGA TCC GAA AAA ATG C-3′) and KP1L (5′-ATA CAA CAC TCT CTA TAT CAG G-3′) (Vallejo et al. 1994). A band of 280 bp was visible in KP1(+) group and was absent in KP1(−). A negative control and positive DNA for KP1(+) and KP1(−) were used to validate the gels. Bands for both molecular markers were detected in a 6% polyacrylamide gel.

Identification of T. rangeli lineages by the intergenic-spacer of the SL gene

T. rangeli lineages were identified by differential amplification of the SL intergenic spacer using the primers TraSL1 (5′-GAA CGG TCG TGT TCT G-3′) and TraSL2 (5′-GAC GGG ATG TGG TGC-3′), as previously described (Maia Da Silva et al. 2007). The expected band sizes for the different lineages are: lineage A (417 bp), lineage B (380 bp), lineage C (480 bp), lineage D (500 bp), and lineage E (987 bp) (Maia Da Silva et al. 2007, 2009).

Sequencing of the SSU-rRNA (18S rRNA) gene

From the samples that were able to be characterized by both the conserved region of the minicircle of kDNA and the intergenic-spacer of the SL gene, a representative subset of samples (n = 17), which represents the geographic and host diversity, were selected for sequencing of a fragment of the SSU-rRNA gene (Table 3). PCR amplifications were conducted with the newly designed primers SSU4_F (5′-GTG CCA GCA CCC GCG GTA AT-3′) and 18Sq1R (5′-CCA CCG ACC AAA AGC GGC CA-3′), using a touchdown PCR profile (Murphy and O'Brien 2007). The PCR products were cleaned with ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and sequencing reactions for both ends were performed with the ABI BigDye chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA) for the external primers mentioned above and the internal primers SSU561F (5′-TGG GAT AAC AAA GGA GCA-3′) and SSU561R (5′-CTG AGA CTG TAA CCT CAA AGC-3′) (Noyes et al. 1996, 1999).

Table 3.

Samples Used for Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Analyses and Respective GenBank Accession Numbers for the 18S rRNA Sequences

| Isolatea | Host | Locality | 18S rRNA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage A | ||||

| San Augustin | Human | Homo sapiens | Colombia | AJ012417 |

| Macias | Human | Homo sapiens | Colombia | AJ012415 |

| H8GS | Human | Homo sapiens | Honduras | AY491744 |

| SMH-03 | Human | Homo sapiens | Guatemala | AY491739 |

| SMH-79 | Human | Homo sapiens | Guatemala | AY491740 |

| MHOM/VE/99/CH-99 | Human | Homo sapiens | Venezuela (Barinas) | AY491742 |

| TryCC_533; MAN/VE/00/LOBITA | Dog | Canis familiaris | Venezuela (Barinas) | EF071572 |

| 220; AT-AEI | Monkey | Saimiri sciureus | Brazil (PA) Marajó | AY491747 |

| 202; AT-ADS | Monkey | Saimiri sciureus | Brazil (PA) Marajó | AY491746 |

| 353; Maloch-05 | Monkey | Callicebus m. cupreus | Brazil (AC) P. de Castro | AY491750 |

| 369; ROma 01 | Opossum | Didelphis marsupialis | Brazil (RO) Monte Negro | AY491748 |

| 382; ROma 06 | Opossum | Didelphis marsupialis | Brazil (RO) Monte Negro | AY491749 |

| P19 | Opossum | Didelphis marsupialis | Brazil (MG) Uberaba | EF071573 |

| P21 | Opossum | Didelphis marsupialis | Brazil (MG) Uberaba | EF071574 |

| Choachi | Triatomine | Rhodnius prolixus | Venezuela | AJ012414 |

| Palma-2 | Triatomine | Rhodnius prolixus | Venezuela | AY491741 |

| TryCC_775; VE/9 | Triatomine | Rhodnius prolixus | Venezuela (Barinas) | EF071575 |

| TryCC_795; VE/3 | Triatomine | Rhodnius robustus I | Venezuela (Trujillo) | EF071576 |

| TryCC_677; ROR-20 | Triatomine | Rhodnius robustus II | Brazil (RO) Monte Negro | EF071577 |

| TryCC_701; ROR-62 | Triatomine | Rhodnius robustus II | Brazil (RO) Monte Negro | EF071578 |

| TryCC_704; ROR-85 | Triatomine | Rhodnius robustus II | Brazil (RO) Monte Negro | EF071579 |

| Lineage B | ||||

| AM80 | Human | Homo sapiens | Brazil (AM) Rio Negro | AY491766 |

| AM11 | Human | Homo sapiens | Brazil (AM) Rio Negro | AY491758 |

| 207; AE-AAA | Monkey | Cebuella pygmaea | Brazil (AC) Rio Branco | AY491752 |

| 194; AE-AAB | Monkey | Cebuella pygmaea | Brazil (AC) Rio Branco | AY491753 |

| 233; 4–30 | Monkey | Saguinus l. labiatus | Brazil (AC) Rio Branco | AY491756 |

| 238; 5–31 | Monkey | Saguinus l. labiatus | Brazil (AC) Rio Branco | AY491754 |

| 236; 8–34 | Monkey | Saguinus f. weddelli | Brazil (AC) Rio Branco | AY491755 |

| 205; M-12229 | Monkey | Aotus sp. | Brazil (AM) Manaus | AY491757 |

| 416; 2495 | Monkey | Alouatta stramineus | Brazil (AM) Rio Negro | AY491760 |

| 427; 2570 | Monkey | Callicebus lugens | Brazil (AM) Rio Negro | AY491751 |

| Saimiri | Monkey | Saimiri sciureus | Brazil (AM) Manaus | AY491768 |

| Preguici | Sloth | Choloepus didactylus | Brazil (PA) Belém | AY491767 |

| Legeri_10 | Anteater | Tamandua tetradactyla | Brazil (PA) Belém | AY491769 |

| Legeri_32 | Anteater | Tamandua tetradactyla | Brazil (PA) Belém | AY491759 |

| 4176 | Triatomine | Rhodnius brethesi | Brazil (AM) Rio Negro | EF071580 |

| Lineage C | ||||

| PG | Human | Homo sapiens | Panama | AJ012416 |

| 1625 | Human | Homo sapiens | El Salvador | AY491738 |

| T. leeuwenhoeki | Sloth | Choloepus didactylus | Panama | AJ012412 |

| RGB | Dog | Canis familiaris | Colombia | AJ009160 |

| SO29 | Triatomine | Rhodnius pallescens | Colombia (Sucre) | EF071581 |

| G5 | Triatomine | Rhodnius pallescens | Colombia (Sucre) | EF071582 |

| TCE_694ci | Triatomine | Panstrongylus chinai | Ecuador (Coamine, Paltas) Loja | |

| TJQ_941ci | Triatomine | Triatoma carrioni | Ecuador (Jacapo, Quilanga) Loja | |

| TCQ_991ci | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Chaquizhca, Calvas) Loja | |

| MBJ_1411s | Opossum | Didelphis marsupialis | Ecuador (El Bejuco, Portoviejo) Manabi | |

| MCQ_1483k | Rodent | Rhipidomys spp. | Ecuador (Chaquizhca, Calvas) Loja | |

| MCQ_1487k | Rodent | Sciurus stramineus | Ecuador (Chaquizhca, Calvas) Loja | |

| MCQ_1516k | Opossum | Didelphis marsupialis | Ecuador (Chaquizhca, Calvas) Loja | |

| TBJ_1540ci | Triatomine | Panstrongylus howardi | Ecuador (El Bejuco, Portoviejo) Manabi | |

| TTO_2151ci | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Tablada del Algodón, Junin) Manabi | |

| TBJ_2239k | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (El Bejuco, Portoviejo) Manabi | |

| TBJ_2268ci | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (El Bejuco, Portoviejo) Manabi | |

| TCI_2307ci | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Chita, San Vicente) Manabi | |

| TLG_2345k | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Liguiqui, Manta) Manabi | |

| TET_2388k | Triatomine | Panstrongylus rufotuberculatus | Ecuador (Estero Seco, Jama) Manabi | |

| TGA_2552ci | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Guara, Calvas) Loja | |

| TCQ_2915k | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Chaquizhca, Calvas) Loja | |

| TCQ_3086k | Triatomine | Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (Chaquizhca, Calvas) Loja | |

| Lineage D | ||||

| SC58 | Rodent | Echimys dasythrix | Brazil (SC) | AY491745 |

| Lineage E | ||||

| TryCC_643; Tra643 | Bat | Platyrrhinus lineatus | Brazil (MS) Miranda | EU867803 |

| Outgroups | ||||

| Trypanosoma sp. | Bat | Rousettus aegyptiacus | Gabon | AJ012418 |

| 1_EA_2008; Trypanosoma sp. | Civet | Nandinia binotata | Cameroon | FM202492 |

| P14; Trypanosoma vespertilionis | Bat | Pipistrellus pipistrellus | England | AJ009166 |

| 2_EA_2008; Trypanosoma sp. | Monkey | Cercopithecus nictitans | Cameroon | FM202493 |

| USP; Trypanosoma conorhini | Rodent | Rattus rattus | Brazil | AJ012411 |

Samples in bold indicate the sequences newly generated for this study.

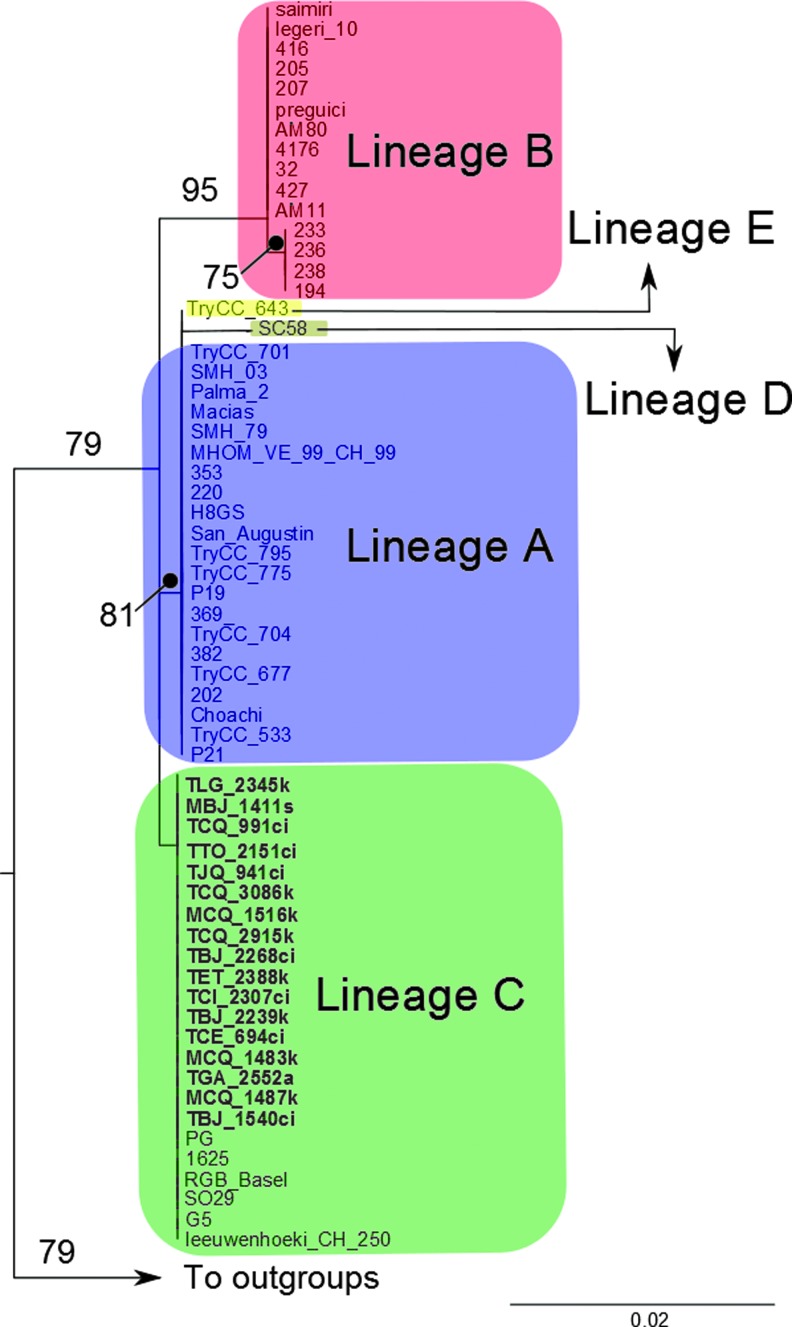

Sequencing of DNA fragments was conducted on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA). Contigs for each trypanosome sample were assembled using Geneious version 8.0.3 (Biomatters 2014) with untrimmed sequences with a percentage of high quality bases (HQ%) higher than 50%, resulting in trimmed sequences with a HQ% higher than 90%; consensus sequences were extracted from each contig. The sequences obtained were aligned with T. rangeli representatives of lineages A to E (Maia Da Silva et al. 2007, 2009) and selected species of the T. cruzi clade as outgroups (Table 3) using the MUSCLE (Edgar 2004) plugin in Geneious. The alignment was checked manually for misplacements and trimmed to 816 bp to ensure completeness of 100% of the sequence length of representatives of all T. rangeli lineages. A phylogenetic analysis using maximum likelihood was performed in RAxML v. 8 (Stamatakis 2014) using the GTRGAMMA model and 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Results

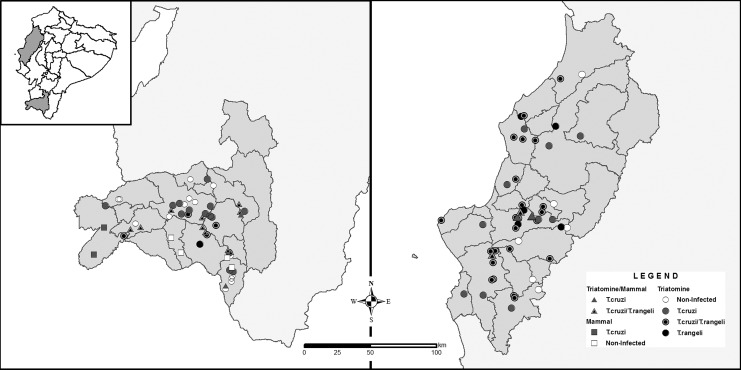

Diversity and distribution of hosts infected by T. rangeli

A total of 3606 samples from triatomines and mammals were screened for the presence of trypanosomatids. Of those, 351 (10%) presented infection for T. rangeli, and from them, 1.25% corresponded to mixed infections with T. cruzi. A higher infection rate was found in Manabí Province than in Loja Province, 14% and 7%, respectively (Table 1) (Fig. 1A, B). T. rangeli had a wide distribution in both regions and was present in more than 60% of the counties included in this study. Along this geographic distribution, mixed infections with T. cruzi were also reported (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Differential detection of T. cruzi and T. rangeli infection of triatomine's intestinal contents by (A) amplification of the conserved regions of the minicircle of kDNA and (B) D7a divergent region of the large subunit ribosomal RNA gene. CC, T. cruzi control; CR, T. rangeli control; CN, negative control. Genotyping of T. rangeli was carried out by (C) the amplification of the conserved regions of the minicircle of kDNA to identify among the groups KP1(+) and KP1(−) and (D) the intergenic spacer of the splice leader (SL) gene to characterize the lineage. TC, T. cruzi control; LA, lineage A control of T. rangeli; LC, lineage C control of T. rangeli; CN, negative control. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/vbz

FIG. 2.

Geographic distribution of T. rangeli and T. cruzi infection in invertebrate (triatomines) and vertebrate (mammal) hosts in southern Ecuador, Loja Province (left), and central coastal Ecuador, Manabí Province (right). Lines indicate county division.

Regarding the mammalian hosts, 18 genera from the order Chiroptera (Artibeus, Desmodus, Glossophaga), Didelphimorphia (Didelphis, Marmosa, Micoureus, Philander), and Rodentia (Aegialomys, Akodon, Cavia, Mus, Rattus, Rhipidomys, Sciurus, Handleyomys, Hoplomys, Proechimys, Transandinomys) were found to be infected with T. rangeli. However, infection rates were <6% (Table 1). With respect to the triatomine hosts, five species were found infected: Panstrongylus chinai, P. rufotuberculatus, P. howardi, Triatoma carrioni, and Rhodnius ecuadoriensis. The species R. ecuadoriensis showed the highest infection rates in both regions (10% and 17%), whereas the other species presented infection rates <5% (Table 1).

T. rangeli was found circulating in all the three habitats (domicile, peridomicile, and sylvatic). Nevertheless, a notably higher infection rate was found in the sylvatic environment (17%) compared with the peridomicile and domestic environments, which presented 7% and 2%, respectively (Table 1).

Genotyping of T. rangeli circulating in vertebrate and invertebrate host

From the 351 samples that were determined to be positive for T. rangeli infection, a representative subset of 111 was characterized by the conserved region of the minicircle of kDNA and the intergenic-spacer of the SL gene. Ninety-nine percent of the samples were classified as KP1(−), independent from the geographic or host origin (Fig. 1C). It was not possible to genotype one sample from R. ecuadoriensis due to the presence of nonspecific bands (Table 2). On the other hand, 80% (n = 89) of the samples (including triatomines and mammals) were determined as lineage C (Fig. 1D), while 20% (n = 22) did not amplify any of the expected bands or amplified bands of not expected size (Table 2).

Sequencing of the SSU-rRNA (18S rRNA) gene

Of the 89 samples that were able to be characterized as KP1(−)/lineage C, a subset of 17 samples were sequenced. Within this subset, we included samples that could not be characterized by PCR of the kDNA (TCQ991) or SL (MBJ1411, TCE694). All samples in this study were identical, and the phylogenetic analysis grouped the sequences with lineage C of T. rangeli (Fig. 3). In the phylogenetic tree, lineage E does not differentiate from lineage A, and there is little differentiation between lineages D and A (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Maximum likelihood tree of isolates of T. rangeli with representatives of five lineages (A–E). Names of isolates in bold represent the Ecuadorian isolates sequenced in this study. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap support values. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/vbz

Discussion

Manabí and Loja Provinces are considered as endemic areas for Chagas disease in Ecuador, and active transmission due to the presence of the parasite T. cruzi and its hosts (triatomines vectors and mammal hosts) has been confirmed (Grijalva et al. 2003, 2005, Pinto et al. 2006, Black et al. 2009). Moreover, the presence of the nonpathogenic T. rangeli has also been reported as overlapping T. cruzi distribution (Pinto et al. 2006, Grijalva et al. 2011, 2012, Villacis et al. 2015). This study confirmed the presence of both species of trypanosomes in 1.25% of the samples. However, it is important to consider that the infection rate reported may be underestimated due to the fact that screening of T. rangeli was carried out in intestinal contents and not in salivary glands or hemolymph. Nevertheless, a broad delineation of the distribution and genetic diversity of T. rangeli circulating in these areas has not been reported until now.

Infection of T. rangeli has been detected in mammals of at least five orders (Didelphimorphia, Chiroptera, Rodentia, Pilosa, and Primates) (Ramirez et al. 2002, Maia da Silva et al. 2004a, b, Cabrine-Santos et al. 2009, Maia da Silva et al. 2009, Ramirez et al. 2014). This study confirmed the presence of T. rangeli in three mammalian orders: Didelphimorphia, Chiroptera, and Rodentia, and in 18 genera, thus extending the report of host diversity for this parasite (Maia da Silva et al. 2004a, b, Pinto et al. 2006, Gurgel-Goncalves et al. 2012). However, infection rates reported in this study are low compared with others previously reported in Didelphimorphia and Chiroptera (Ramirez et al. 2002, Ramirez et al. 2014).

Extensive research of the vector–parasite relationships between T. rangeli and triatomine insects supports that the distribution of T. rangeli is closely related to the distribution of triatomines of the genus Rhodnius (Gaunt and Miles 2000, Machado et al. 2001, Urrea et al. 2005, Vallejo et al. 2007, Pulido et al. 2008, Salazar-Anton et al. 2009, Vallejo et al. 2009, Garcia et al. 2012). Even though the species of the genus Rhodnius are particularly susceptible to infection of salivary glands by T. rangeli, such infection has been also reported in Triatoma dimidiata (Marinkelle 1968, D'Alessandro-Bacigalupo and Gore Saravia 1991). However, the vector capacity due to the presence of infective stages of T. rangeli has only been proven in Rhodnius (Guhl and Vallejo 2003). While other triatomines species of the genera Triatoma and Panstrongylus have also reported to be naturally infected with T. rangeli, these reports are restricted to infection in the intestines (D'Alessandro-Bacigalupo and Gore Saravia 1991, Vallejo et al. 2002, Villacis et al. 2015). This study extends the species of triatomines naturally infected with T. rangeli to P. chinai, P. rufotuberculatus, and T. carrioni. Although, finding other species than Rhodnius infected with this parasite is feasible, our results do not imply the capacity of transmission of these species because the samples came from intestinal contents isolates and not from salivary glands.

R. ecuadoriensis was the species of triatomine with the highest infection rates. Although this study reports T. rangeli infecting intestinal contents, the natural and experimental infection of salivary glands has been previously reported in this species of triatomine (Cuba 1975, Guhl and Vallejo 2003, Urrea et al. 2005). However, its capacity to transmit T. rangeli has not been evaluated yet. Recent studies have demonstrated that R. ecuadoriensis is an important threat for Chagas disease transmission due to its wide geographical distribution, high infection rates with T. cruzi, good vector efficiency, and capacity of adaptation to different habitats (Villacis et al. 2008, Grijalva and Villacis 2009, Suarez-Davalos et al. 2010, Grijalva et al. 2012, 2014). In this regard, the presence of R. ecuadoriensis, infected with T. rangeli, constitutes an important element to consider when the distribution of trypanosomes is evaluated in Chagas disease endemic areas. Although the infection rates in the domestic and peridomestic environments were low (<7%), the high infection rates of T. rangeli in R. ecuadoriensis from sylvatic environments (17%) and the proven synanthropic tendency of the sylvatic populations of this species (Grijalva and Villacis 2009, Suarez-Davalos et al. 2010) indicate a risk for an increase of T. rangeli in domestic/peridomestic environments with its well-known consequences of being a confounding factor for Chagas disease diagnosis (Saldana and Sousa 1996a, b). The characteristics of R. ecuadoriensis and its important percentage of infection with T. rangeli, together with the morphological and genetic similarities that it shares with the pathogenic T. cruzi, need to be addressed when the biological and epidemiological scenarios are assessed, especially considering that infections of T. rangeli in humans have been previously reported in South America (Guhl and Vallejo 2003, Saldana et al. 2005).

Only T. rangeli KP1(−)/lineage C was found, even though the samples came from a variety of host species (triatomines and mammals) and two geographical regions that are ecologically different. This study complements the geographic range for KP1(−) in the Andean region, which has been previously described in Colombia and Peru (Vallejo et al. 2009, Urrea et al. 2011) and also for lineage C, which has been previously reported in Central America and Colombia (Maia da Silva et al. 2004a, b). It was not possible to identify the lineage of 22 out of 111 samples with the SL gene. However, two of these samples (MBJ1411 and TCE694) were included in the subset for sequencing, and they were characterized as lineage C. We relate this gap of information with the source of DNA. These samples were obtained directly from the hosts (intestinal contents or blood), and the amount of T. rangeli DNA was difficult to assess. Although some previous attempts have been carried out to detect Trypanosoma from field samples, especially T. cruzi (Hamano et al. 2001, Marcet et al. 2006), all of them rely on the highly repetitive regions as the kDNA.

The distribution of the different genotypes of T. rangeli is affected by the trypanolytic capability of the species of Rhodnius (Pulido et al. 2008, Vallejo et al. 2009). Indeed, T. rangeli distribution is not associated with the vertebrate host but with the biogeographical distribution of Rhodnius species, even in areas where sympatric Rhodnius species coexist (Machado et al. 2001, Salazar-Anton et al. 2009, Urrea et al. 2011). The presence of the genotype T. rangeli KP1(−) associated with R. ecuadoriensis is in total accordance with what has been previously described for this species of triatomine (Urrea et al. 2005, 2011) and with what is expected regarding lineage C (Vallejo et al. 2009). Thus, the predominantly presence of R. ecuadoriensis in the study area also explains the presence of T. rangeli KP1(−)/lineage C in the samples from mammal hosts.

A phenotypic analysis of antennas and wings from R. ecuadoriensis demonstrated differences between the triatomine population of Loja and Manabí that suggest a speciation process (Villacis et al. 2010), especially considering that both geographic areas are separated by the Andes mountains, which constitute a natural barrier. An effect of triatomine subdivision was not evident in the T. rangeli samples of this study with the SSU-rRNA gene. However, detection of population structure among the T. rangeli KP1 (−/lineage C isolates with other molecular markers is possible, especially in light of the recent subdivision found by microsatellite typing on T. rangeli KP1(−) that was related to geographical location or co-evolution of parasites and hosts (Sincero et al. 2015). The access to the recently published complete genome of T. rangeli (Stoco et al. 2014) will provide new tools for elucidating the complex biology of this parasite and its interaction with its hosts.

Conclusions

This work reports the natural infection by T. rangeli in species of three mammalian orders (Didelphimorphia, Chiroptera, Rodentia) and four triatomine insect species (P. chinai, P. rufotuberculatus, R. ecuadoriensis, and T. carrioni) in southern (Loja) and central coastal (Manabí) Ecuador. Despite its presence in all the three habitats (domestic, peridomestic, and sylvatic), a higher infection rate was found in the sylvatic habitat and related to the presence of R. ecuadoriensis. A representative subset of T. rangeli that includes samples from a wide geographic area and a variety of host species (triatomines and mammals) was classified as KP1(−) and to the lineage C. No diversity was found among the SSU-rRNA gene, even though the samples came from ecologically different areas where subdivision of R. ecuadoriensis populations has been detected by phenotypic analysis.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was received from the Global Infectious Diseases Training Grant–Fogarty International Center–National Institutes of Health (D43TW008261); the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (DMID/NIAID/NIH (1 R15 AI077896-01); the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)–United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)/World Bank/World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases Research Capability Strengthening Group (grant ID A20785 and A60655); the European Union Seventh Framework Programme, contract number 223034 (ChagasEpiNet); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine; PEW Latin American Fellows Program in the Biomedical Sciences (ID:00026195); and Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (I13048).

Special thanks are directed to the personnel of the National Chagas Control Program–National Vector Borne–Disease Control Service, Ecuadorian Ministry of Health; to Francisco J. Ayala for the critical review of the manuscript; and to María Augusta Chávez and Freddy Proaño from the University of the Army Force–ESPE for their academic assistance. Technical assistance was provided by Anita Villacís, César Yumiseva, Fernanda Latorre, and Andrea Zurita from the Center of Infectious Disease Research at Pontifical Catholic University and Uriel Alvarado and Daniel Zabala from the Laboratorio de de Investigaciones en Parasitología Tropical at Universidad de Tolima.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Biomatters. Geneious v.8.0.3. 2014. Available at www.geneious.com

- Black CL, Ocana S, Riner D, Costales JA, et al. Household risk factors for Trypanosoma cruzi seropositivity in two geographic regions of Ecuador. J Parasitol 2007; 93:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CL, Ocana-Mayorga S, Riner DK, Costales JA, et al. Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi in rural Ecuador and clustering of seropositivity within households. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 81:1035–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrine-Santos M, Ferreira KA, Tosi LR, Lages-Silva E, et al. Karyotype variability in KP1(+) and KP1(−) strains of Trypanosoma rangeli isolated in Brazil and Colombia. Acta Trop 2009; 110:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiari E, Dias JC, Lana M, Chiari CA. Hemocultures for the parasitological diagnosis of human chronic Chagas' disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 1989; 22:19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottontail VM, Kalko EK, Cottontail I, Wellinghausen N, et al. High local diversity of Trypanosoma in a common bat species, and implications for the biogeography and taxonomy of the T. cruzi clade. PLoS One 2014; 9:e108603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuba CA. [Peruvian strain of Trypanosoma rangeli. IV. Observations on its development and morphogenesis in the hemocele and salivary glands of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis]. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 1975; 17:283–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandro A, de Hincapie O. Rhodnius neivai: A new experimental vector of Trypanosoma rangeli. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1986; 35:512–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandro-Bacigalupo A, Gore Saravia N. Trypanosoma rangeli. In: Kreier JP, Baker JR, eds. Parasitic Protozoa. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991:v. <1–10> [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa MA, da Silva Fonseca T, Dos Santos BN, Dos Santos Pereira SM, et al. Trypanosoma rangeli Tejera, 1920, in chronic Chagas' disease patients under ambulatory care at the Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute (IPEC-Fiocruz, Brazil). Parasitol Res 2008; 103:697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani Marquez D, Rodrigues-Ottaiano C, Monica Oliveira R, Pedrosa AL, Cabrine-Santos M, et al. Susceptibility of different triatomine species to Trypanosoma rangeli experimental infection. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2006; 6:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia ES, Castro DP, Figueiredo MB, Azambuja P. Parasite-mediated interactions within the insect vector: Trypanosoma rangeli strategies. Parasit Vectors 2012; 5:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt M, Miles M. The ecotopes and evolution of triatomine bugs (triatominae) and their associated trypanosomes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2000; 95:557–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Escalante L, Paredes RA, Costales JA, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors for Trypanosoma cruzi infection in the Amazon region of Ecuador. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 69:380–385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Palomeque-Rodriguez FS, Costales JA, Davila S, et al. High household infestation rates by synanthropic vectors of Chagas disease in southern Ecuador. J Med Entomol 2005; 42:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Villacis AG. Presence of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis in sylvatic habitats in the southern highlands (Loja Province) of Ecuador. J Med Entomol 2009; 46:708–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Villacis AG, Ocana-Mayorga S, Yumiseva CA, et al. Limitations of selective deltamethrin application for triatomine control in central coastal Ecuador. Parasit Vectors 2011; 4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Suarez-Davalos V, Villacis AG, Ocana-Mayorga S, et al. Ecological factors related to the widespread distribution of sylvatic Rhodnius ecuadoriensis populations in southern Ecuador. Parasit Vectors 2012; 5:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Teran D, Dangles O. Dynamics of sylvatic chagas disease vectors in coastal Ecuador is driven by changes in land cover. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisard EC, Steindel M, Guarneri AA, Eger-Mangrich I, et al. Characterization of Trypanosoma rangeli strains isolated in Central and South America: an overview. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1999; 94:203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhl F, Vallejo GA. Trypanosoma (Herpetosoma) rangeli Tejera, 1920: An updated review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003; 98:435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhl F, Hudson L, Marinkelle CJ, Morgan SJ, et al. Antibody response to experimental Trypanosoma rangeli infection and its implications for immunodiagnosis of South American trypanosomiasis. Acta Trop 1985; 42:311–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgel-Goncalves R, Cura C, Schijman AG, Cuba CA. Infestation of Mauritia flexuosa palms by triatomines (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli in the Brazilian savanna. Acta Trop 2012; 121:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamano S, Horio M, Miura S, Higo H, et al. Detection of kinetoplast DNA of Trypanosoma cruzi from dried feces of triatomine bugs by PCR. Parasitol Int 2001; 50:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado PE, Eger-Mangrich I, Rosa G, Koerich LB, et al. Differential susceptibility of triatomines of the genus Rhodnius to Trypanosoma rangeli strains from different geographical origins. Int J Parasitol 2001; 31:632–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia da Silva F, Rodrigues AC, Campaner M, Takata CS, et al. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of Trypanosoma rangeli and allied species from human, monkeys and other sylvatic mammals of the Brazilian Amazon disclosed a new group and a species-specific marker. Parasitology 2004a; 128:283–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia da Silva F, Noyes H, Campaner M, Junqueira AC, et al. Phylogeny, taxonomy and grouping of Trypanosoma rangeli isolates from man, triatomines and sylvatic mammals from widespread geographical origin based on SSU and ITS ribosomal sequences. Parasitology 2004b; 129:549–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia Da Silva F, Junqueira AC, Campaner M, Rodrigues AC, et al. Comparative phylogeography of Trypanosoma rangeli and Rhodnius (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) supports a long coexistence of parasite lineages and their sympatric vectors. Mol Ecol 2007; 16:3361–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia da Silva F, Marcili A, Lima L, Cavazzana M Jr, et al. Trypanosoma rangeli isolates of bats from Central Brazil: genotyping and phylogenetic analysis enable description of a new lineage using spliced-leader gene sequences. Acta Trop 2009; 109:199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcet PL, Duffy T, Cardinal MV, Burgos JM, et al. PCR-based screening and lineage identification of Trypanosoma cruzi directly from faecal samples of triatomine bugs from northwestern Argentina. Parasitology 2006; 132:57–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkelle CJ. Triatoma dimidiata capitata, a natural vector of Trypanosoma rangeli in Colombia. Rev Biol Trop 1968; 15:203–205 [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro VM, Jimenez M, Dias JC, Zeledon R. Chagas disease in dogs from endemic areas of Costa Rica. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2002; 97:491–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy WJ, O'Brien SJ. Designing and optimizing comparative anchor primers for comparative gene mapping and phylogenetic inference. Nat Protoc 2007; 2:3022–3030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes HA, Camps AP, Chance ML. Leishmania herreri (Kinetoplastida; Trypanosomatidae) is more closely related to Endotrypanum (Kinetoplastida; Trypanosomatidae) than to Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1996; 80:119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes HA, Stevens JR, Teixeira M, Phelan J, et al. A nested PCR for the ssrRNA gene detects Trypanosoma binneyi in the platypus and Trypanosoma sp. in wombats and kangaroos in Australia. Int J Parasitol 1999; 29:331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda V, Saldana A, Monfante I, Santamaria A, et al. Prevalence of trypanosome infections in dogs from Chagas disease endemic regions in Panama, Central America. Vet Parasitol 2011; 178:360–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto CM, Ocana-Mayorga S, Lascano MS, Grijalva MJ. Infection by trypanosomes in marsupials and rodents associated with human dwellings in Ecuador. J Parasitol 2006; 92:1251–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulido XC, Perez G, Vallejo GA. Preliminary characterization of a Rhodnius prolixus hemolymph trypanolytic protein, this being a determinant of Trypanosoma rangeli KP1(+) and KP1(−) subpopulations' vectorial ability. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008; 103:172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JD, Tapia-Calle G, Munoz-Cruz G, Poveda C, et al. Trypanosome species in neo-tropical bats: Biological, evolutionary and epidemiological implications. Infect Genet Evol 2014; 22:250–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez LE, Lages-Silva E, Alvarenga-Franco F, Matos A, et al. High prevalence of Trypanosoma rangeli and Trypanosoma cruzi in opossums and triatomids in a formerly-endemic area of Chagas disease in Southeast Brazil. Acta Trop 2002; 84:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Anton F, Urrea DA, Guhl F, Arevalo C, et al. Trypanosoma rangeli genotypes association with Rhodnius prolixus and R. pallescens allopatric distribution in Central America. Infect Genet Evol 2009; 9:1306–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana A, Sousa OE. Trypanosoma rangeli: Epimastigote immunogenicity and cross-reaction with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Parasitol 1996a; 82:363–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana A, Sousa OE. Trypanosoma rangeli and Trypanosoma cruzi: Cross-reaction among their immunogenic components. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1996b; 91:81–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana A, Samudio F, Miranda A, Herrera LM, et al. Predominance of Trypanosoma rangeli infection in children from a Chagas disease endemic area in the west-shore of the Panama canal. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2005; 100:729–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sincero TC, Stoco PH, Steindel M, Vallejo GA, et al. Trypanosoma rangeli displays a clonal population structure, revealing a subdivision of KP1(−) strains and the ancestry of the Amazonian group. Int J Parasitol 2015; 45:225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souto RP, Vargas N, Zingales B. Trypanosoma rangeli: Discrimination from Trypanosoma cruzi based on a variable domain from the large subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Exp Parasitol 1999; 91:306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:1312–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoco PH, Wagner G, Talavera-Lopez C, Gerber A, et al. Genome of the avirulent human-infective trypanosome—Trypanosoma rangeli. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Davalos V, Dangles O, Villacis AG, Grijalva MJ. Microdistribution of sylvatic triatomine populations in central-coastal Ecuador. J Med Entomol 2010; 47:80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urrea DA, Carranza JC, Cuba CA, Gurgel-Goncalves R, et al. Molecular characterisation of Trypanosoma rangeli strains isolated from Rhodnius ecuadoriensis in Peru, R. colombiensis in Colombia and R. pallescens in Panama, supports a co-evolutionary association between parasites and vectors. Infect Genet Evol 2005; 5:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urrea DA, Guhl F, Herrera CP, Falla A, et al. Sequence analysis of the spliced-leader intergenic region (SL-IR) and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) of Trypanosoma rangeli strains isolated from Rhodnius ecuadoriensis, R. colombiensis, R. pallescens and R. prolixus suggests a degree of co-evolution between parasites and vectors. Acta Trop 2011; 120:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo GA, Marinkelle CJ, Guhl F, de Sanchez N. [Behavior of the infection and morphologic differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi and T. rangeli in the intestine of the vector Rhodnius prolixus]. Rev Bras Biol 1988; 48:577–587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo GA, Macedo AM, Chiari E, Pena SD. Kinetoplast DNA from Trypanosoma rangeli contains two distinct classes of minicircles with different size and molecular organization. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1994; 67:245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo GA, Guhl F, Chiari E, Macedo AM. Species specific detection of Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli in vector and mammalian hosts by polymerase chain reaction amplification of kinetoplast minicircle DNA. Acta Trop 1999; 72:203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo GA, Guhl F, Carranza JC, Lozano LE, et al. kDNA markers define two major Trypanosoma rangeli lineages in Latin-America. Acta Trop 2002; 81:77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo GA, Guhl F, Carranza JC, Triana O, et al. [Trypanosoma rangeli parasite-vector-vertebrate interactions and their relationship to the systematics and epidemiology of American trypanosomiasis]. Biomedica 2007; 27(Suppl 1):110–118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo GA, Guhl F, Schaub GA. Triatominae–Trypanosoma cruzi/T. rangeli: Vector–parasite interactions. Acta Trop 2009; 110:137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacis AG, Arcos-Teran L, Grijalva MJ. Life cycle, feeding and defecation patterns of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis (Lent & Leon 1958) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) under laboratory conditions. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008; 103:690–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacis AG, Grijalva MJ, Catala SS. Phenotypic variability of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis populations at the Ecuadorian central and southern Andean region. J Med Entomol 2010; 47:1034–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacis AG, Ocana-Mayorga S, Lascano MS, Yumiseva CA, et al. Abundance, natural infection with trypanosomes, and food source of an endemic species of triatomine, Panstrongylus howardi (Neiva 1911), on the Ecuadorian central coast. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:187–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virreira M, Alonso-Vega C, Solano M, Jijena J, et al. Congenital Chagas disease in Bolivia is not associated with DNA polymorphism of Trypanosoma cruzi. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006; 75:871–879 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases. In: Crompton DWT, ed. First WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases. France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo M, Lewis MD, Carrasco HJ, Acosta N, et al. Resolution of multiclonal infections of Trypanosoma cruzi from naturally infected triatomine bugs and from experimentally infected mice by direct plating on a sensitive solid medium. Int J Parasitol 2007; 37:111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]