Abstract

Inhabitants of Túquerres in the Colombian Andes have a 25-fold higher risk of gastric cancer than inhabitants of the coastal town Tumaco, despite similar H. pylori prevalences. The gastric microbiota was recently shown in animal models to accelerate the development of H. pylori-induced precancerous lesions. 20 individuals from each town, matched for age and sex, were selected, and gastric microbiota analyses were performed by deep sequencing of amplified 16S rDNA. In parallel, analyses of H. pylori status, carriage of the cag pathogenicity island and assignment of H. pylori to phylogeographic groups were performed to test for correlations between H. pylori strain properties and microbiota composition. The gastric microbiota composition was highly variable between individuals, but showed a significant correlation with the town of origin. Multiple OTUs were detected exclusively in either Tumaco or Túquerres. Two operational taxonomic units (OTUs), Leptotrichia wadei and a Veillonella sp., were significantly more abundant in Túquerres, and 16 OTUs, including a Staphylococcus sp. were significantly more abundant in Tumaco. There was no significant correlation of H. pylori phylogeographic population or carriage of the cagPAI with microbiota composition. From these data, testable hypotheses can be generated and examined in suitable animal models and prospective clinical trials.

With an estimated 1 million new cases per year, and 720,000 deaths, gastric cancer is a leading cause of morbidity worldwide, and the third most common cause of cancer-related death1. Helicobacter pylori infection is the best-studied risk factor for gastric cancer, and 89% of non-cardia gastric cancer cases are estimated to be attributable to H. pylori infection1. However, cancer risk can vary dramatically between populations with relatively similar prevalence of H. pylori infection. The Colombian department of Nariño in the southwest of the country includes both coastal regions, where stomach cancer is comparatively rare (6 cases per 100 000 inhabitants in 1976), and high-altitude parts of the Andes, where gastric cancer rates are strikingly high (150 cases/100,000 inhabitants in 1976)2. The contrasting rates of gastric cancer are associated with very similar rates of H. pylori infection between regions, with 95% of inhabitants testing seropositive for the pathogen both in coastal and in high-altitude regions3.

Despite four decades of research, the reasons for this “altitude enigma” remain incompletely understood. It has been suggested that altitude is a surrogate for multifactorial influences of host and bacterial genotypes, as well as dietary and environmental variables which may all contribute to the effect2,4,5,6. We and others have demonstrated the high incidence of helminthiasis in select Colombian populations, particularly children3. Our studies3 suggest that the immune response to H. pylori infection in the low-risk coastal population is predominantly type Th2 and that it may be related to intestinal helminthiasis. This observation is consistent with our report that intestinal helminthiasis reduced gastric atrophy, a premalignant lesion, in the C57BL/6 mouse model of Helicobacter gastritis7. Our recent studies in insulin-gastrin (INS-GAS) mice demonstrating a H. pylori- associated attenuation of premalignant lesions in these mice coinfected with the nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus also support this hypothesis8.

Recently, Kodaman et al.9 demonstrated that cancer risk was highest in individuals whose host and bacterial ancestries were mismatched, possibly disrupting a balance generated by thousands of years of host-microbe coevolution. Cancer risk was particularly high when individuals of Amerindian descent carried H. pylori with largely African ancestry, while individuals with matching host ancestry and H. pylori strain had a lower risk.

After a period where H. pylori was thought to be the only physiologically relevant bacterial colonizer of the human gastric mucosa, several studies provided evidence that bacteria other than H. pylori can regularly be detected in gastric biopsies, although the ecological role of these bacteria remains unclear. However, several lines of evidence point at a potential role of the microbiota in gastrointestinal carcinogenesis. We have recently shown in a transgenic mouse model of gastric carcinogenesis, the INS-GAS mouse, that the presence of a gastrointestinal microbiota strongly accelerated the induction of gastric preneoplasic lesions by Helicobacter pylori10. This study was further supported in the INS-GAS mono-associated H. pylori model where the addition of a select intestinal microflora accelerated gastric cancer11. These studies raise the possibility that the non-H. pylori gastric microbiota contributes to gastric carcinogenesis, and that components of the gastric microbiota may play a role in causation and/or serve as biomarkers of gastric cancer risk.

In this study, we have analyzed the composition of the gastric microbiota of individuals from the Colombian high-risk and low-risk areas of Túquerres and Tumaco, respectively. The data show significant differences between towns, and permitted us to identify bacterial species that only occurred in either region, generating testable hypotheses for future clinical and experimental studies.

Results

Gastric microbiota composition in individuals from Tumaco and Túquerres (Colombia)

Antral gastric biopsies from two groups of 20 individuals each from two cities in Colombia, Tumaco, a coastal town with low gastric cancer risk, or Túquerres, a town in the Andes mountains with high gastric cancer risk, were subjected to gastric microbiota analysis. Individuals were matched by age and sex (Table 1), and intentionally selected with similar assignment of gastric disease.

Table 1. Samples used in this study, with characteristics of the corresponding study participants.

| Sample ID | Sample pair | Sex of participant | Age of participant | Location | Histo-pathological diagnosis | Histo-pathological score | H. pylori status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT5106 | 1 | F | 40 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT2108 | 1 | F | 41 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT5136 | 2 | F | 41 | Tumaco | NAG | 3 | Positive |

| MT2118 | 2 | F | 41 | Túquerres | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT5176 | 3 | M | 42 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT2120 | 3 | M | 41 | Túquerres | NAG | 3 | Positive |

| MT5139 | 4 | F | 43 | Tumaco | NAG | 1 | Positive |

| MT2131 | 4 | F | 41 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT5117 | 5 | F | 44 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.75 | Positive |

| MT2133 | 5 | F | 42 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.75 | Positive |

| MT5124 | 6 | F | 46 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT2124 | 6 | F | 43 | Túquerres | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT5135 | 7 | M | 45 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT2130 | 7 | M | 46 | Túquerres | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT5101 | 8 | F | 47 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT2102 | 8 | F | 44 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT5105 | 9 | F | 47 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT2122 | 9 | F | 45 | Túquerres | NAG | 3 | Positive |

| MT5119 | 10 | F | 48 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT2115 | 10 | F | 50 | Túquerres | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT5120 | 11 | F | 48 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT2127 | 11 | F | 50 | Túquerres | MAG | 4 | Positive |

| MT5111 | 12 | M | 50 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT2156 | 12 | M | 50 | Túquerres | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT5126 | 13 | M | 51 | Tumaco | NAG | 3 | Positive |

| MT2136 | 13 | M | 52 | Túquerres | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT5116 | 14 | F | 51 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.33 | Positive |

| MT2129 | 14 | F | 51 | Túquerres | NAG | 2 | Positive |

| MT5155 | 15 | M | 52 | Tumaco | NAG | 2 | Positive |

| MT2160 | 15 | M | 52 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.75 | Positive |

| MT5174 | 16 | M | 52 | Tumaco | MAG-IM | 4.8 | Negative |

| MT2113 | 16 | M | 52 | Túquerres | NAG | 1.67 | Positive |

| MT5107 | 17 | F | 55 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT2114 | 17 | F | 55 | Túquerres | MAG-IM | 4.6 | Positive |

| MT5114 | 18 | M | 56 | Tumaco | MAG | 3.75 | Positive |

| MT2109 | 18 | M | 57 | Túquerres | MAG-IM | 4.4 | Positive |

| MT5113 | 19 | M | 59 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT2112 | 19 | M | 57 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

| MT5131 | 20 | F | 59 | Tumaco | NAG | 2.67 | Positive |

| MT2106 | 20 | F | 60 | Túquerres | MAG | 3.5 | Positive |

NAG, non-atrophic gastritis; MAG, multifocal atrophic gastritis without intestinal metaplasia; MAG-IM: multifocal atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia. H. pylori status according to Steiner stain.

DNA was purified from the biopsies using a DNA extraction protocol optimized for efficient lysis of diverse bacterial taxa, a fragment of the conserved 16S rDNA gene was amplified with a set of broad range primers recognizing highly conserved sequence motifs, and the amplicons were then sequenced with high coverage using Roche 454 FLX + technology.

The full dataset (before subsampling) consisted of a total of 647,914 sequences, with 6960 to 32,147 sequences per sample (Supplementary Dataset S1). 555,430 of these sequences could be identified to species level (85.7%), resulting in a total of 187 species and 575 97% identity clusters of sequences not identified to the species level. For the purpose of this study, both identified species and 97% identity clusters were considered as operative taxonomic units (OTUs).

Where not noted otherwise, analyses were based on a rarefied version of this dataset, which consisted of 6960 sequences per sample (total number of sequences, 278,400; for rarefaction curves see Supplementary Fig. 1). Within this subsampled dataset, 229,384 sequences (82%) were identified to species level; it contained 125 identifiable species and 299 other OTUs (Supplementary Dataset S2). Individual samples contained 4 to 199 OTUs (Supplementary Dataset S2), which included 1 to 6952 sequences identified as members of the Helicobacteraceae (Supplementary Dataset S2, Supplementary Table S1). Helicobacteraceae sequences not identified to species were treated as potential members of the species H. pylori.

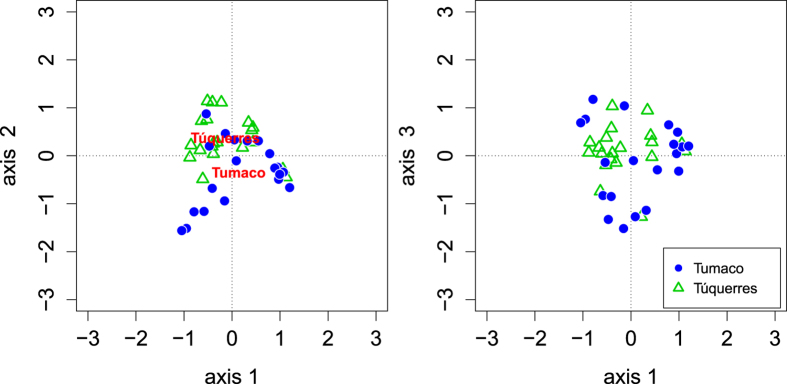

We first asked whether the microbiota composition differed between the two towns, and whether the microbiota composition was correlated with patient characteristics such as histological diagnosis. To accomplish this, we used Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of the microbiota data and fitted patient characteristics and town of origin onto the resulting graphs. This analysis was based on unweighted UniFrac distances (Fig. 1), which incorporate the phylogenetic relatedness of the OTUs in the dataset when comparing the similarity between samples. The town of origin was found to be significantly correlated with the pattern of microbiota composition (envfit factor fitting, confirmed by Analysis of Molecular Variance AMOVA based on Jaccard index dissimilarities, p = 0.004, n = 40). No significant correlations were obtained between the microbiota composition and histological score, diagnosis, patient sex or patient age, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 1. PCoA analysis of the subsampled microbiota data, based on UniFrac distances, with significantly correlated sample characteristics fitted to the graph (p < = 0.05; for p values see table 2).

Table 2. Results of envfit analyses testing for correlation of patient characteristics with microbiota composition patterns detected in PCoA graph.

| p value of correlation with PCoA plane |

||

|---|---|---|

| axis 1-axis 2 | axis 1-axis 3 | |

| all samples included (n = 40) | ||

| histological diagnosis | 0.14 | 0.29 |

| histopathology score | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| patient age | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| patient sex | 0.55 | 0.19 |

| town | 0.0012 | 0.24 |

| samples with available cagPAI status (n = 38) | ||

| cagPAI status | 0.25 | 0.77 |

| samples with H. pylori population data (n = 33) | ||

| % AA1 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| % AA1 > 20%? | 0.39 | 0.39 |

| % AA1 > 50%? | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| modern H. pylori population | 0.47 | 0.42 |

P values were based on 10,000 permutations. P values ≤ 0.05 (bold text) are considered significant.

Distribution patterns of individual microbiota components between towns

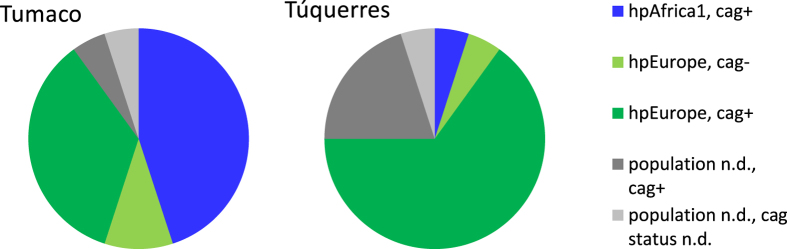

We next analysed whether the individual bacterial OTUs occurred more abundantly in individuals from either Tumaco or Túquerres. The presence and abundance of individual OTUs was highly variable between individuals (Fig. 2, Supplementary Dataset S2). Nevertheless, Metastats-based analysis of differential abundances12 identified 2 OTUs that were significantly more abundant in Túquerres and 16 OTUs significantly more abundant in Tumaco individuals (false discovery rate q < 0.05, 20 samples per town, sample-specific OTUs excluded; Table 3). The OTUs significantly more abundant in Túquerres were identified as Leptotrichia wadei and as a member of the genus Veillonella, respectively. While the OTUs that were significantly more abundant in the Túquerres group could also be detected in individual samples from Tumaco, the OTUs significantly more abundant in the Tumaco patient group were not identified in the samples from Túquerres (in the subsampled dataset). The Tumaco-specific bacteria included an OTU identified as a member of the genus Staphylococcus which was found in 35% of the Tumaco samples (7 of 20 samples), the species Neisseria flavescens (4 samples), a member of the family Porphyromonadaceae (4 samples), an OTU of the genus Flavobacterium (4 samples), and an OTU belonging to the candidate division TM7 (3 samples).

Figure 2. Venn diagram visualizing the number of town-specific and shared OTUs.

Numbers of sample-specific OTUs indicated.

Table 3. OTUs with significantly different occurrence among towns (according to Metastats analysis), with false discovery rate q. Excluding OTUs found in one sample only.

| OTU name | OTU counts in sample sets |

Number of samples containing OTU |

q | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumaco | Túquerres | Tumaco | Túquerres | ||

| significantly more in Túquerres | |||||

| Leptotrichia wadei | 1 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 0.017 |

| OTU 508 (Veillonella sp.) | 1 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 0.007 |

| significantly more in Tumaco | |||||

| OTU 566 (Staphylococcus sp.) | 4068 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0.007 |

| Neisseria flavescens | 113 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0.007 |

| OTU 359 (“Porphyromonadaceae” gen. sp.) | 42 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0.007 |

| OTU 438 (Flavobacterium sp.) | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0.047 |

| OTU 549 (TM7-genera incertae sedis) | 18 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.003 |

| OTU 430 (Rothia sp.) | 136 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.007 |

| Prevotella oris | 39 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.007 |

| Capnocytophaga gingivalis | 33 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.007 |

| OTU 541 (Actinomyces sp.) | 31 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.007 |

| OTU 486 (Haematobacter sp.) | 25 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.007 |

| OTU 362 (Flavobacteriaceae gen. sp.) | 23 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.007 |

| OTU 515 (Actinomyces sp.) | 18 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.003 |

| OTU 506 (Sphingomonadaceae gen. sp.) | 18 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.003 |

| Streptococcus oralis | 14 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.008 |

| OTU 440 (Porphyromonas sp.) | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.015 |

| OTU 491 (Neisseria sp.) | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.015 |

Based on the rooted phylogenetic tree that had been constructed for the calculation of UniFrac distances (Supplementary Fig. S2), we next tested whether additional phylogenetic groups above the OTU level were differently abundant between the Tumaco and Túquerres individuals. We used the phylogenetic tree to calculate the branch length difference (cophenetic distance) between the individual OTUs (using cophenetic.phylo of the R package phyloseq). We examined clades at the distance levels commonly used as proxy for the difference between species (cophenetic distance 0.03), genera (cophenetic distance 0.05) and families (cophenetic distance 0.1). The dataset’s OTUs were merged at these three distance levels (using tip_glom of the phyloseq package), and the resulting merged OTUs were examined using Metastats. While most clades identified as being significantly different in abundance between Tumaco and Túquerres contained individual OTUs that had already been identified as being different in abundance in the first analysis, some additional clades were identified as differently abundant between towns: At a cophenetic distance of 0.03 (“approximate species level”), 4 additional multi-OTU-clades were found to be significantly more abundant in Tumaco. This included two Tumaco-specific clades of OTUs classified as Actinomyces spp., one clade consisting of Streptomyces spp. and another clade of OTUs identified as Catonella spp. (Supplementary Dataset S3). No additional significantly different clade was identified at a cophenetic distance of 0.05 (“approximate genus level”) (Supplementary Dataset S4). At a cophenetic distance of 0.1 (“approximate family level”), three additional clades were identified as significantly more abundant in Tumaco. These were identified as a clade of Flavobacteriaceae, members of the genus Prevotella, and members of the genus Mycoplasma, respectively (Supplementary Dataset S5).

We further tested for direct associations of patient characteristics with individual non-H. pylori OTUs (Supplementary Dataset S6). This analysis was based on three versions of the OTU dataset: an abundance-based and a binary version of the subsampled dataset as well as an abundance-based non-subsampled version of the full OTU dataset. From all three versions, all Helicobacteraceae OTUs were removed. While no OTU was correlated with the histopathology score, a number of OTUs were correlated with the diagnosis of MAG-IM (categorical factor regression; false discovery rate ≤0.05). Most of these were identified as members of oral and respiratory tract groups, including several OTUs classified as Actinomyces, Prevotella and Streptococcus. Correlation analysis based on Spearman’s rank correlation (false discovery rate ≤0.05) identified one Streptococcus OTU positively correlated with the number of Helicobacteraceae sequences in the subsampled abundance-based dataset. The species Actinomyces odontolyticus, which was also one of the OTUs associated with MAG-IM, was identified as positively correlated with patient age in both the abundance-based and the binary subsampled dataset; it occurred both in the Tumaco and the Túquerres groups. In the non-subsampled dataset, a Pseudomonas OTU, an OTU identified as a member of Xanthomonadaceae and an OTU of the genus Prevotella were found to be correlated with age (Supplementary Dataset S6).

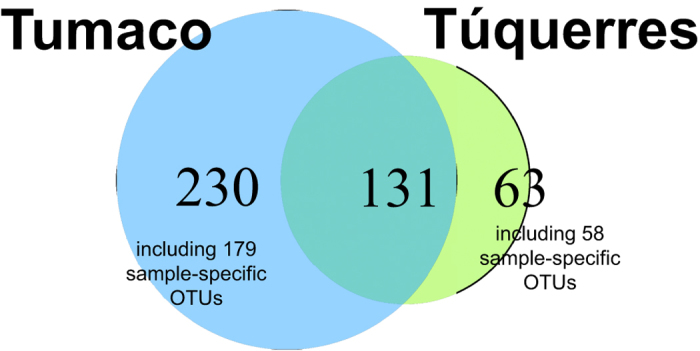

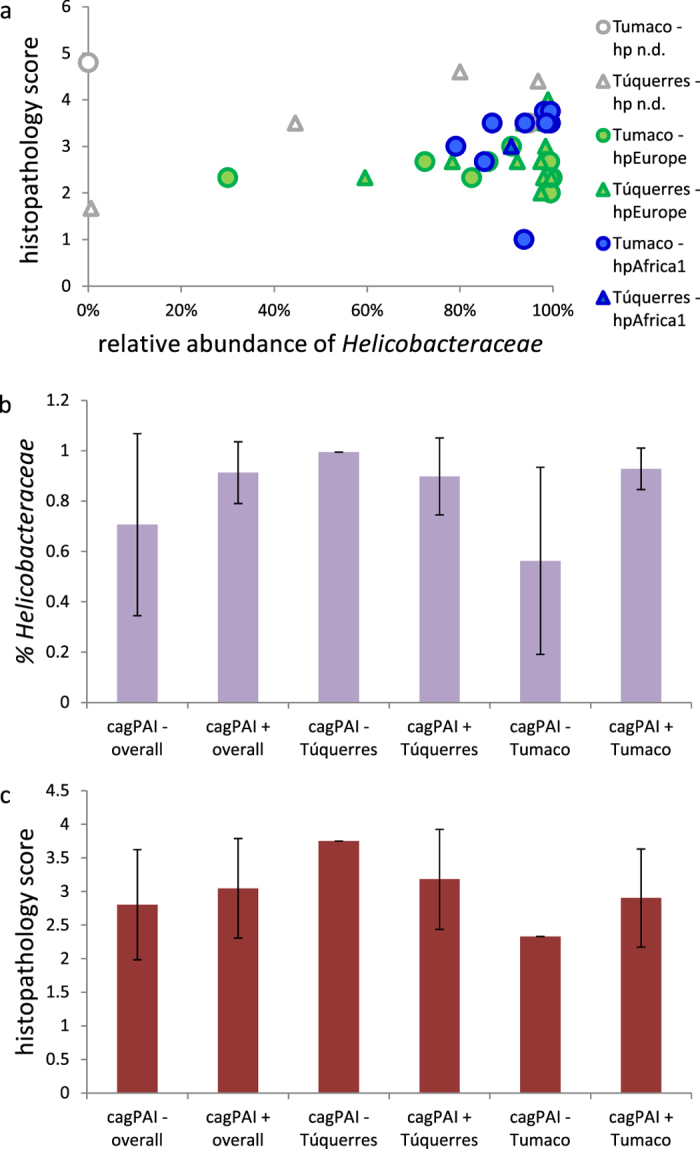

H. pylori and the gastric microbiota composition

The presence of H. pylori infection alters gastric physiology and is thus likely to affect the gastric microbiota. While all but one individual included in this study were initially tested as H. pylori-positive by histology, and while H. pylori sequences could be identified from all samples, infecting H. pylori strains were diverse. H. pylori can be subdivided into phylogeographic populations with distinct geographic distribution and differential carriage of virulence factors. Specific combinations of host ancestry and H. pylori populations were recently shown to be associated with more severe gastric lesions in individuals from a Colombian patient cohort similar to our cohort9. In order to evaluate a potential influence of H. pylori phylogeography on the gastric microbiota composition, we performed multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) for H. pylori strains isolated from biopsy samples from the same individuals for whom the microbiota analysis had been performed. H. pylori isolates were available for 15 samples from Túquerres and 18 samples from Tumaco. One H. pylori isolate from Túquerres and 9 isolates from Tumaco were assigned to the H. pylori population hpAfrica1 (Túquerres isolate: subpopulation hspSAfrica; the 9 hpAfrica1 Tumaco isolates: subpopulation hspWAfrica); the remaining isolates were all identified as hpEurope (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2). In our dataset, a difference in gastric lesions associated with hpAfrica1 and hpEurope strains could only be detected for Tumaco samples, in which hpAfrica1 strains were associated with significantly higher histopathology scores (3.13 ± 0.87 vs. 2.48 ± 0.30, p = 0.012, Wilcoxon rank sum test, see Supplementary Dataset S7, Fig. 4a). When comparing samples associated with hpEurope strains between towns, histopathology scores from Túquerres were significantly higher than those from Tumaco (2.98 ± 0.63 vs. 2.48 ± 0.30, mean ± standard deviation; p = 0.019, Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction, Supplementary Dataset S7). This difference was not detected between the complete sample sets of the two towns. Modern H. pylori strains are mosaics that have arisen by recombination between members of six known ancestral H. pylori populations. The composition of the H. pylori isolates from the six know ancestral H. pylori populations was investigated with an additional STRUCTURE analysis assuming recombination of the 6 known ancestral H. pylori populations according to the linkage model. Among the samples from Túquerres, the maximum proportion of Ancestral Africa 1 (AA1) ancestry (32.9%) was found in the strain identified as hspSAfrica; four other Túquerres strains had more than 20% AA1 ancestry (22.5–24.1%). Among the Tumaco isolates, 8 of the 18 isolates were predominantly (>50%) of AA1 ancestry, and a total of 12 samples were identified as more than 20% AA1 (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Table S3). A significant correlation between histopathology scores and proportion of AA1 ancestry was detected for Tumaco samples (rho = 0.53, p = 0.022), but not for the samples from Túquerres (Supplementary Dataset S7).

Figure 3. Overview over H. pylori population assignment and sample cagPAI status.

N = 20 for each town.

Figure 4. Histopathology score and relative abundance of Helicobacteraceae in the full dataset in relation to H. pylori population and cagPAI status.

(a), histopathology score vs. abundance of Helicobacteraceae, plotted by H. pylori population. (b), abundance of Helicobacteraceae by cagPAI status and town. (c), histopathology score by cagPAI status and town. For p values see Supplementary Dataset S7.

We next tested for correlations between population and ancestry of the infecting H. pylori strains and the respective stomach microbiota (factor fitting on the PCoA ordination). Neither the H. pylori population nor the proportion of AA1 ancestry was found to be significantly correlated with the microbiota composition (Table 2). In addition, no individual OTU was found to be correlated with H. pylori population or the proportion of AA1 ancestry.

Independently of the H. pylori population, presence of the cag pathogenicity island (cagPAI) is an important determinant of H. pylori virulence. Using several PCR assays on both biopsy samples and individual H. pylori strains for each patient, we could assign a cagPAI status to 19 samples for each location (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2). While most samples (35) tested positive, one sample from Túquerres and two samples from Tumaco were cagPAI-negative. All three cagPAI-negative strains were assigned to the H. pylori population hpEurope (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2). Both in the full dataset and in the Tumaco samples, the cagPAI-negative status was associated with lower abundances of Helicobacteraceae sequences and histopathology scores. Due to the low number of cagPAI-negative samples and non-normality of the data, significance of these differences could not be assessed (Fig. 4b,c; Supplementary Dataset S7). While factor fitting on the PCoA analysis identified no correlation of cagPAI status with the overall microbiota composition (Table 2), regression analysis identified 9 OTUs of the non-subsampled abundance-based dataset as correlated with a negative cagPAI status (Supplementary Dataset S6).

Discussion

Human populations with similarly high H. pylori prevalence can display strong differences of gastric cancer risk. This has motivated intensive studies of both, differences of carcinogenic potential between H. pylori strains and diverse co-carcinogenic factors including host susceptibility and environmental conditions. In this study, we have analyzed the composition of the gastric microbiota of two human populations in Colombia with starkly different gastric cancer risks, with the aim to identify microbiota components that might be involved in the development of gastric cancer initiated by chronic H. pylori infection, or serve as biomarkers of gastric cancer risk.

Recent studies in animal models have provided evidence of a potential role of the non-H. pylori microbiota in H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis10,11,13. The gastric microbiota was shown to accelerate and enhance the development of preneoplastic lesions and adenocarcinoma in the transgenic INS-GAS mouse model10,11. The complete microbiota or individual microbiota components were reported to add additional noxious effects by formation of carcinogenic nitrosamines in hypochlorhydric stomachs14, or beneficial effects, by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines15,16,17,18, increasing gastric ulcer healing13,19, or inhibiting H. pylori growth and colonization15,20. The stomach microbiota in turn can be influenced by H. pylori infection, at least in gerbils and mice10,21,22. Also, the presence of intestinal helminths in the H. pylori INS-GAS mouse model ameliorated gastric atrophy and dysplasia which are important precursor lesions to gastrointestinal intraepithelial neoplasia (GIN). Helminth co-infection resulted in increased Foxp3 cells in the corpus and inhibited gastric colonization with enteric bacteria8.

Our data clearly show that the gastric microbiota composition differed between the two towns. Most of the OTUs that we identified as significantly more abundant in either high-risk Túquerres or low-risk Tumaco (Table 3) were classified as taxa previously identified in “healthy” human microbiomes, and in stomach samples23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Nevertheless, one of the OTUs significantly more abundant in Túquerres, the fusobacterium Leptorichia wadei, can be associated with necrotizing enterocolitis and bacteremia in chemotherapy patients34. Among the OTUs that might be associated with the lower cancer risk of the Tumaco inhabitants, Staphylococcus OTU 566 occurred in 9 Tumaco samples and in one of the samples from Túquerres (non-subsampled full dataset). The genus Staphylococcus is part of the human normal microbiota, and several species of this genus were previously reported in stomach samples30,31,33. Another Tumaco-associated OTU is the species Streptococcus oralis, an oral cavity commensal35,36, which was found to be significantly less abundant in endodontic infections than in other parts of oral cavity37. These two OTUs might warrant further investigation regarding a possible involvement in protection against inflammatory processes and cancer development.

Further interesting OTUs include the Tumaco-specific OTU 486, which was classified as belonging to the genus Haematobacter, a recently described genus that is most often isolated from human blood, although the type strain was isolated from the nose of a patient with aspiration pneumonia38. Among the few available studies on this genus is a case report of endocarditis possibly caused by a Haematobacter-like organism39. OTU 430, classified as Rothia sp., and Capnocytophaga gingivalis were both associated with the town of Tumaco, and OTU 430 was additionally correlated with a diagnosis of MAG-IM. Both the genus Rothia and the species Capnocytophaga gingivalis are otherwise associated with healthy oral surfaces29,35,36,37,40, and the genus Rothia is regularly found in stomach samples24,28,30,31,33. As both these taxa are not normally linked to exacerbation of inflammatory or carcinogenic processes, both probably represent mainly swallowed organisms that can survive longer or bloom in more physiologically compromised (and probably less acidic) stomachs.

Similarly to the town-associated OTUs, most of the OTUs identified as correlated with a diagnosis of MAG-IM (Supplementary Dataset S6) were identified as taxa previously identified from stomach samples23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,41. All but one belong to taxa that are part of the normal flora of the human mouth29,35,36,37,40,42,43,44, and many are also found in intestinal samples29; the exception to this is OTU 319, a member of the genus Pelomonas that is otherwise associated with water samples45,46. In spite of their occurrence in healthy microbiome samples, several MAG-IM-associated OTUs are known to be linked to inflammatory pathologies, albeit in the mouth37,47. This includes two representatives (OTU 492 and P. oris) of the genus Prevotella, which contains several periodontal pathogens. The genus Granulicatella, which is represented by G. adiacens and OTU 336, has been linked to root canal infections37; Mogibacterium timidum and Anaeroglobus geminatus are periodontal pathogens47, and the genus Eubacterium (OTU 461) contains a newly identified oral pathogen, the species Eubacterium saphenum. Additionally, four members of the genus Streptococcus were correlated with MAG-IM: OTU 327 and the species S. infantis, S. salivarius and S. sanguinis. Finding such a high number of Streptococcus OTUs to be associated with pathological lesions was surprising, but is probably due to the high abundance and diversity of this genus in our samples: the subsampled dataset contains 61 OTUs classified as Streptococcus spp. (Supplementary Dataset S2). Conversely, although streptococci are members of the healthy human oral microbiota that are regularly found in stomach samples24,28,30,31,33, an increased abundance of this genus in antral gastritis and in peptic ulcer disease has been reported28,33. Interestingly, many of the Streptococcus species are urease positive, as are several Staphylococcus species, and their presence in the stomach, in part, may be attributed to the enzyme which provides a protective advantage for survival in an acidic environment. In our dataset, the only non-Helicobacteraceae OTU that significantly increased in abundance with increasing dominance of Helicobacteraceae was also classified as Streptococcus sp. (OTU 568). An unidentified member of this genus was previously reported to be part of a probiotic mix that accelerated gastric ulcer healing in rats by inducing the expression of growth factors which enhance processes such as epithelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis19. On the other hand, the species S. sinensis was found to be more abundant in NAG than in MAG-IM and even less abundant in gastric cancer48.

The low pH of the gastric lumen, together with the activity of pepsins, is the major reason why the stomach is relatively poor in bacteria. Conditions affecting gastric acidity are likely to have a major influence on the gastric microbiota. Overgrowth of the stomach microbiota is a known complication of acid-suppressive therapy. As mentioned above, we thus cannot exclude that the increased occurrence of the MAG-IM-correlated OTUs might result from increased survival in MAG-IM damaged stomachs which have an elevated pH. Nevertheless, they represent candidates that might be of interest for targeted studies on the influence of individual taxa on the development of gastric pathology.

We note that the ecology of the gastric microbiota has been studied very little. Open questions include the stability of the gastric microbiota over time and the differentiation between passing bacteria and bacteria causing a stable colonization. A comparative analysis of saliva and mucosal gastric microbiota samples from individuals from a cohort with contrasting gastric cancer risks might help to resolve these questions.

The differences in stomach cancer risk in high vs. low altitude regions in Colombia have been linked to a variety of factors, including differences of the colonizing H. pylori strains. In order to evaluate whether the microbiota composition was independent of H. pylori type, or rather reflected differences of the colonizing H. pylori strain, we also characterized one H. pylori isolate per sample and tested DNA extracted from biopsies for selected genes of the cagPAI. In agreement with previous studies from the region, 50% of H. pylori strains isolated from low-risk Tumaco were assigned to the H. pylori biogeographic population hpAfrica1, while the remainder of the Tumaco strains and almost all strains from the high-risk region around Túquerres were hpEurope49. However, no significant correlations of the overall gastric microbiota composition with either H. pylori population type or carriage of the cagPAI were detected, indicating that the differences of gastric microbiota composition in our analysis were largely independent of the colonizing H. pylori strains. We note that cagPAI-deficient H. pylori were present in the respective individuals in lower abundance than cagPAI positive bacteria, although significance of this finding could not be assessed statistically. The cagPAI has been suggested to provide a fitness benefit to H. pylori, but different densities of H. pylori for cagPAI-positive vs. -negative bacteria had not been reported before, an observation that warrants further investigations.

A recent study has demonstrated enhanced virulence of H. pylori strains with higher proportion of Ancestral Africa 1 (AA1) ancestry in human hosts with predominantly Amerindian ancestry9. This is concordant with the observed difference between high- and low-risk regions, because the inhabitants of high-risk Andean regions are mainly of Amerindian and European ancestry, while the inhabitants of the coastal low-risk region are mainly of African ancestry with significant proportions of Amerindian and European ancestry. Although human genetic data are not available for the individuals of our cohort, based on the published data, we expected a correlation between biopsy histopathology score and the fraction of AA1 ancestry in the H. pylori strains for samples from Túquerres only. In our data however, such a correlation was only detected in Tumaco (Supplementary Dataset S7). This might be due to the relatively small number of Túquerres subjects harbouring H. pylori with increased AA1 ancestry within this study, which was designed to test differences of microbiota composition in subjects matched for age, sex, and pathology scores.

Our study shows differences of microbiota composition between the two populations. From these data, testable hypotheses can be generated that can be examined in suitable animal models (e.g. the INS-GAS model) where candidate strains can be examined for their accelerating or protective effect on the development of H. pylori-induced preneoplastic lesions. Such studies are now under way in our laboratories. Even if our current study does not permit us to infer causality between microbiota components and pathology, microbiota composition data may prove informative about environmental factors that contribute to gastric cancer risk. As one example, dietary differences between the regions include higher consumption of fresh vegetables, fruit and seafood in the low-risk regions and higher consumption of potatoes and fava beans in the high-risk region4, which may contribute to differences in both microbiota and stomach pathologies.

Methods

Study participants, samples and histopathology

Subjects between 40 and 60 years old with dyspeptic symptoms that warranted upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy were recruited in Tumaco and Túquerres in 2010. Subjects that had received proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, or antimicrobials during the 30 day period previous to the endoscopic procedure were excluded from this study. Other exclusion criteria were major diseases or previous gastrectomy. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Ethics Committees of the participating hospitals in Nariño and the Universidad del Valle in Cali, Colombia and the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University approved all study protocols, and all experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. See Supplemental Methods for details.

DNA techniques and H. pylori multilocus haplotype analysis

See Supplemental Methods for details

Microbiota analysis and bioinformatics analysis

The microbiota composition was analysed as described in Yang et al.50, with slight modifications. 16S rDNA amplicon reads were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive under study accession number PRJEB11763. See Supplemental Methods for details.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yang, I. et al. Different gastric microbiota compositions in two human populations with high and low gastric cancer risk in Colombia. Sci. Rep. 6, 18594; doi: 10.1038/srep18594 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Nell for help with assignment of H. pylori strains to phylogeographic populations, and Zharah Fiebig, Birgit Brenneke, Friederike Kops, Yvonne Speidel and Kerstin Ellrott for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants DFG SFB 900/A1 and DFG SFB 900/Z1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to S.S., grant DFG SFB 900/B6 from the DFG to C.J., BMBF grant HELDIVPAT in the framework of the ERA-NET PathoGenoMics to S.S. and C.J., and grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health P01 CA28842 (to P.C., K.T.W. and J.G.F), P30 ES002109 (to J.G.F), R01 CA77955 (to R.M.P.), P01 CA116087 (to R.M.P. and K.T.W.), P30 DK058404 (to R.M.P.), R01 DK058587 (to R.M.P.), R01 DK053620 (to K.T.W.) and R01 CA190612 (to K.T.W.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions I.Y., M.B.P., P.C., C.J., J.G.F. and S.S. designed the study. S.W. and J.R.-G. performed DNA sequencing and H. pylori culture, respectively. I.Y., C.J. and S.S. analyzed the data. M.B.P., L.E.B., M.C.Y., J.R.-G., A.G.D., K.T.W. and R.M.P. provided patient samples and clinical information. I.Y. and S.S. wrote the first version of the manuscript with text input from M.B.P., C.J. and J.G.F. All authors commented on the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- IARC Helicobacter pylori Working Group. Helicobacter pylori eradication as a strategy for preventing gastric cancer. 8, (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014).

- Correa P. & Piazuelo M. B. Gastric cancer: The Colombian enigma. Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol. 25, 334–337 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Whary M. T. et al. Intestinal helminthiasis in Colombian children promotes a Th2 response to Helicobacter pylori: possible implications for gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 14, 1464–1469 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo M. C. et al. Plasma selenium measurements in subjects from areas with contrasting gastric cancer risks in Colombia. Arch. Med. Res. 39, 443–451 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J. et al. Gastric cancer incidence and mortality is associated with altitude in the mountainous regions of Pacific Latin America. Cancer Causes Control CCC 24, 249–256 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo L. E., van Doom L.-J., Realpe J. L. & Correa P. Virulence-associated genotypes of Helicobacter pylori: do they explain the African enigma? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 97, 2839–2842 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. G. et al. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat. Med. 6, 536–542 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whary M. T. et al. Helminth co-infection in Helicobacter pylori infected INS-GAS mice attenuates gastric premalignant lesions of epithelial dysplasia and glandular atrophy and preserves colonization resistance of the stomach to lower bowel microbiota. Microbes Infect. Inst. Pasteur 16, 345–355 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodaman N. et al. Human and Helicobacter pylori coevolution shapes the risk of gastric disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 1455–1460 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren J. L. et al. Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori–infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 140, 210–220 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lertpiriyapong K. et al. Gastric colonisation with a restricted commensal microbiota replicates the promotion of neoplastic lesions by diverse intestinal microbiota in the Helicobacter pylori INS-GAS mouse model of gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 63, 54–63 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. R., Nagarajan N. & Pop M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000352 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo F., Linsalata M. & Orlando A. Probiotics against neoplastic transformation of gastric mucosa: effects on cell proliferation and polyamine metabolism. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 20, 13258–13272 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J. O. & Weitzberg E. Biology of nitrogen oxides in the gastrointestinal tract. Gut 62, 616–629 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh P.-S. et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection by the probiotic strains Lactobacillus johnsonii MH-68 and “L. salivarius ssp. salicinius AP-32. Helicobacter 17, 466–477 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiraworawong T. et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of gastric-derived Lactobacillus plantarum XB7 in the context of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 19, 144–155 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Z. et al. Coinfection with enterohepatic Helicobacter species can ameliorate or promote Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric pathology in C57BL/6 mice. Infect. Immun. 79, 3861–3871 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke L. B. et al. Concurrent Helicobacter bilis infection in C57BL/6 mice attenuates proinflammatory H. pylori-induced gastric pathology. Infect. Immun. 77, 2147–2158 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmani P., De Simone C. & Chadee K. The probiotic mixture VSL#3 accelerates gastric ulcer healing by stimulating vascular endothelial growth factor. PloS One 8, e58671 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S., Leite A. M. O., Ruas-Madiedo P. & Mayo B. Probiotic and technological properties of Lactobacillus spp. strains from the human stomach in the search for potential candidates against gastric microbial dysbiosis. Front. Microbiol. 5, 766 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J. C. et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 338, 120–123 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki T. et al. Comparative analysis of gastric bacterial microbiota in Mongolian gerbils after long-term infection with Helicobacter pylori. Microb. Pathog. 53, 12–18 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma B. K. et al. Intragastric bacterial activity and nitrosation before, during, and after treatment with omeprazole. Br. Med. J. Clin. Res. Ed 289, 717–719 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bik E. M. et al. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 732–737 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S. et al. Non-Helicobacter bacterial flora rarely develops in the gastric mucosal layer of children. Dig. Dis. Sci. 51, 641–646 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A. F. et al. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PloS One 3, e2836 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicksved J. et al. Molecular characterization of the stomach microbiota in patients with gastric cancer and in controls. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 509–516 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-X. et al. Bacterial microbiota profiling in gastritis without Helicobacter pylori infection or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. PloS One 4, e7985 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns J. C. et al. Bacterial biogeography of the human digestive tract. Sci. Rep. 1, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. et al. Bacterial flora concurrent with Helicobacter pylori in the stomach of patients with upper gastrointestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 18, 1257–1261 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S., Cabrera-Rubio R., Mira A., Suárez A. & Mayo B. Microbiological survey of the human gastric ecosystem using culturing and pyrosequencing methods. Microb. Ecol. 65, 763–772 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rosenvinge E. C. et al. Immune status, antibiotic medication and pH are associated with changes in the stomach fluid microbiota. ISME J. 7, 1354–1366 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi Y. et al. Culturable bacterial microbiota of the stomach of Helicobacter pylori positive and negative gastric disease patients. ScientificWorldJournal 2014, 610421 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier M. R., Slechta E. S., Goulston C., Fisher M. A. & Hanson K. E. Leptotrichia bacteremia in patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1228–1232 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggio M. P. et al. Molecular identification of bacteria on the tongue dorsum of subjects with and without halitosis. Oral Dis. 14, 251–258 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. et al. The Human Oral Microbiome Database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2010, baq013 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao W. W. et al. Microbial transformation from normal oral microbiota to acute endodontic infections. BMC Genomics 13, 345 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel L. O. et al. Identification of ‘Haematobacter’, a new genus of aerobic Gram-negative rods isolated from clinical specimens, and reclassification of Rhodobacter massiliensis as ‘Haematobacter massiliensis comb. nov.’ J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1238–1243 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher A., Li L., Han X. Y. & Trautner B. W. Aortic valve endocarditis possibly caused by a Haematobacter-like species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 3791–3793 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberstein B. et al. Digestive tract microbiota in healthy volunteers. Clin. São Paulo Braz. 62, 47–54 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse S. M., Ye Y., Zhou Y. & Fodor A. A. A core human microbiome as viewed through 16S rRNA sequence clusters. PloS One 7, e34242 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. Deep sequencing of the oral microbiome reveals signatures of periodontal disease. PloS One 7, e37919 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaddox L. M. et al. Microbiological characterization in children with aggressive periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 91, 927–933 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.-H. & Yokota A. Reclassification of Alcaligenes latus strains IAM 12599T and IAM 12664 and Pseudomonas saccharophila as Azohydromonas lata gen. nov., comb. nov., Azohydromonas australica sp. nov. and Pelomonas saccharophila gen. nov., comb. nov., respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 2419–2425 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomila M., Bowien B., Falsen E., Moore E. R. B. & Lalucat J. Description of Pelomonas aquatica sp. nov. and Pelomonas puraquae sp. nov., isolated from industrial and haemodialysis water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 2629–2635 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Chaparro P. J. et al. Newly identified pathogens associated with periodontitis: a systematic review. J. Dent. Res. 93, 846–858 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviles-Jimenez F., Vazquez-Jimenez F., Medrano-Guzman R., Mantilla A. & Torres J. Stomach microbiota composition varies between patients with non-atrophic gastritis and patients with intestinal type of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 4, 4202 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sablet T. et al. Phylogeographic origin of Helicobacter pylori is a determinant of gastric cancer risk. Gut 60, 1189–1195 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang I. et al. Intestinal microbiota composition of interleukin-10 deficient C57BL/6J mice and susceptibility to Helicobacter hepaticus-induced colitis. PLoS ONE 8, e70783 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.