Abstract

Despite progress in the development of drugs efficiently targeting cancer cells, treatments of metastatic tumours are often ineffective. The now well established dependency of cancer cells on their microenvironment1 suggests that targeting the non-cancer cell component of the tumour might form the basis for the development of novel therapeutic approaches. However, the as yet poorly characterised contribution of host responses during tumour growth and metastatic progression represents a limitation to exploiting this approach. Here we identify neutrophils as the main component and driver of metastatic establishment within the (pre-)metastatic lung microenvironment in mouse breast cancer models. Neutrophils have a fundamental role in inflammatory responses and their contribution to tumourigenesis is still controversial2-4. Using various strategies to block neutrophil recruitment to the pre-metastatic site, we demonstrate that neutrophils specifically support metastatic initiation. Importantly, we find that neutrophil-derived leukotrienes aid the colonization of distant tissue by selectively expanding the sub-pool of cancer cells that retain high tumorigenic potential. Genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of the leukotriene-generating enzyme arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (Alox5) abrogates neutrophil pro-metastatic activity and consequently reduces metastasis. Our results reveal the efficacy of using targeted therapy against a specific tumour microenvironment component and indicate that neutrophil Alox5 inhibition may limit metastatic progression.

In the presence of a growing tumour, subclinical changes in the leukocyte composition at distant sites have been reported to favour metastatic growth5-7. Cancer cells within a tumour are heterogeneous and retain different tumorigenic potentials. Nonetheless, metastasis-initiating cells (MICs) depend on a favourable microenvironment to efficiently grow at the distant site8-10. We therefore reasoned that an altered presence of leukocytes within distant tissue of tumour-bearing hosts might influence specific subsets of disseminating cancer cells. We investigated this hypothesis using the lung metastatic MMTV-polyoma middle T antigen (PyMT) mammary tumour mouse model, which allows monitoring of the cell sub-population functionally-defined by a higher metastasis initiation ability (CD24+CD90+ MICs)8.

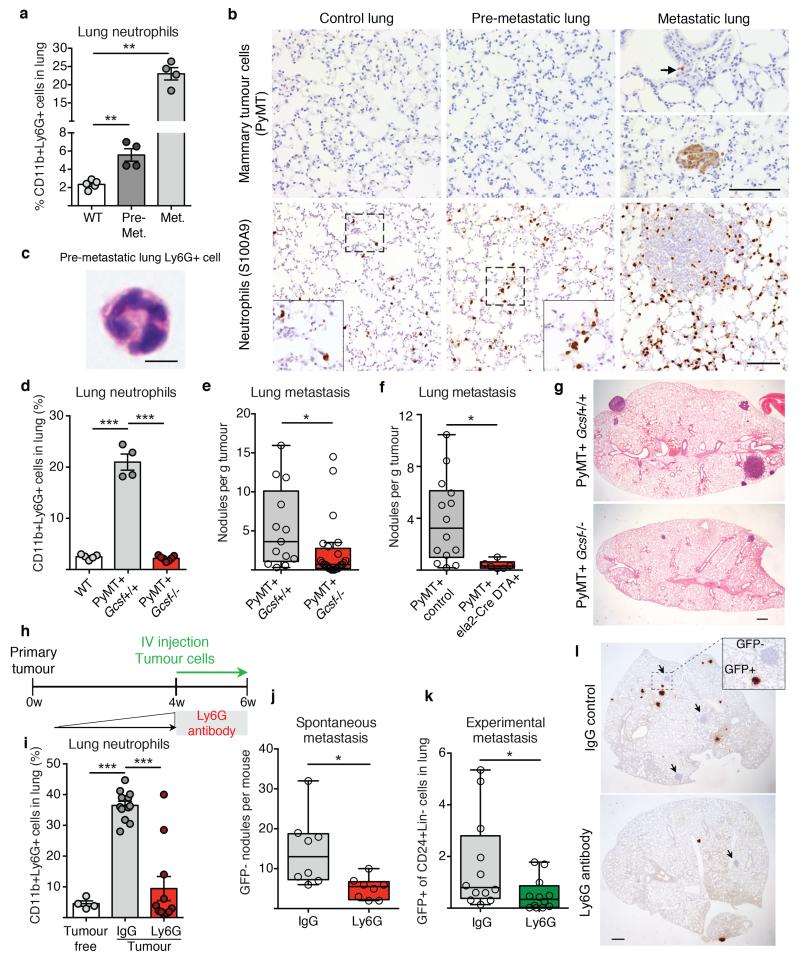

In accordance with previous reports11, we found CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils to be systemically mobilised in MMTV-PyMT tumour-bearing mice and, despite their low frequency within the primary tumour microenvironment, they they were the main immune component that increased in metastatic lungs (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a-l). Importantly, CD11b+Ly6G+ cells accumulated in the lung before cancer cells infiltrated the tissue (pre-metastatic lung) and their numbers increased during metastatic progression (metastatic lung) (Fig. 1a,b). We addressed the functional relevance of high CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophil numbers by analysing metastatic progression of MMTV-PyMT tumour-bearing mice in a neutropenic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (Gcsf)-null background. Mice deficient in G-CSF expression developing mammary tumours failed to accumulate neutrophils in the lungs (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Notably, genetic neutropenia resulted in a robust reduction of spontaneous lung metastasis, despite not affecting primary tumour growth (Fig. 1e,g and Extended Data Fig. 2b). No differences in lung macrophages compared to wild-type mice were detected (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Lack of G-CSF expression by cancer cells altered neither lung neutrophil accumulation nor metastasis (Extended Data Fig. 2d). In an alternative genetic strategy for neutrophil depletion, we crossed MMTV-PyMT+ mice with neutrophil elastase (Ela2)-Cre and with ROSA-Flox-STOP-Flox diphtheria toxin (DTA) mice. Here, neutrophil-specific Cre expression led to DTA-mediated reduction of lung neutrophils in tumour-bearing mice, without altering lung macrophages and circulating myeloid cells or activating bone marrow natural killer (NK) and cytotoxic T cells (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f,h-j). Importantly, metastatic progression was impaired in MMTV-PyMT+-Ela2-Cre-DTA+ mice without affecting primary tumour growth (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 2f,g).

Figure 1. Neutrophils infiltrate pre-metastatic lungs and favour metastasis.

a, b, Analysis of wild-type (WT) or MMTV-PyMT+ mice. a, Lung neutrophils frequencies determined by flow cytometry (n = 5 (wild-type), n = 4 (pre-metastatic lung), n = 4 (metastatic lung)). Met., metastatic. b, Lung neutrophils or cancer cells determined by histology staining for S100A9 or PyMT (brown). Scale bars, 100 μm. Magnifications in inserts. c, Haematoxylin & eosin (H&E)-stained neutrophil. Scale bar, 5 μm. d, Lung neutrophil quantification by flow cytometry (n = 5 (wild-type), n = 4 (PyMT+ Gcsf+/+), n = 7 (PyMT+ Gcsf−/−)). e, f, Spontaneous metastasis of MMTV-PyMT+ Gcsf+/+ (n = 13) or MMTV-PyMT+ Gcsf−/− (n = 24) (e) and MMTV-PyMT+ control (n = 14) or MMTV-PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+ (n = 6) mice (f). g, Representative H&E-stained sections of lung. Scale bar, 500 μm. h, Experimental setup for neutrophil depletion. i, Flow cytometric lung neutrophil quantification (n = 4 (tumour-free), n = 12 (IgG tumour), n = 11 (Ly6G tumour)). j, k, Spontaneous (n = 8 per group) (j) and experimental metastasis (n = 12 per group) (k). Lin, CD45 CD31 TER119. l, Histological GFP-stained lung sections including close-up on spontaneous (arrow) and experimental metastases (brown). Scale bar, 500μm. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Since lung neutrophil increase precedes cancer cell infiltration (Fig. 1b), we focused on the CD11b+Ly6G+ cells accumulating in the early phase of lung colonization. We established mammary gland tumours by orthotopic transplantation to synchronize tumour growth, distant neutrophil accumulation and metastatic progression (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The comparison of tumour-induced CD11b+Ly6G+ cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils from healthy lungs revealed minor variations as messenger RNA expression of only two of seven tested neutrophil-secreted factors showed changes (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Tumour-mobilized lung neutrophils appeared morphologically mature (Fig. 1c) and the upregulation of CD31 suggests increased lung infiltration12 (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Together, these data indicate that, at this time point, the tumour-induced CD11b+Ly6G+ cells in the lung are mature neutrophils similar to the ones found in healthy lungs. As neutrophils in the tumour context are reported to act as myeloid derived suppressor cells13, we investigated the presence of an anticancer immune environment within the pre-metastatic lung of immune-competent mice. We used anti-Ly6G blocking antibody to deplete neutrophils during the pre-metastatic stage (Extended Data Fig. 4a). No significant differences were found in the frequencies and activation of various immune components as consequence of neutrophil depletion, in particular in cytotoxic T and NK cells (Extended Data Fig. 4b-o and 5a-i). To explore further the functional contribution of lung neutrophils to metastasis independently of potential immunosuppression, we performed time-controlled neutrophil depletion with anti-Ly6G antibody in immune-compromised mice (Rag1-null) harbouring primary tumours. Remarkably, pre-metastatic neutrophil depletion during metastatic colonization caused a decrease of spontaneous metastasis (Fig. 1h-j,l). Concomitantly, lungs of the same mice were synchronously seeded with cancer cells isolated from MMTV-PyMT+ actin-green fluorescent protein (GFP) tumours by intravenous injection to initiate lung colonization (Fig. 1h). Notably, GFP+ cancer cells colonizing neutrophil-depleted lungs were significantly reduced, revealing the relevance of lung neutrophils specifically during metastatic initiation (Fig. 1k,l). No alterations were found in extravasation efficiency of labelled cancer cells (data not shown). Although we cannot exclude a contribution of other cells to a favourable pre-metastatic environment5-7, such as monocytes14, these results reveal that the breast tumour-induced systemic accumulation of neutrophils coincidentally acts as a pre-metastatic niche in tissue targeted for metastatic dissemination.

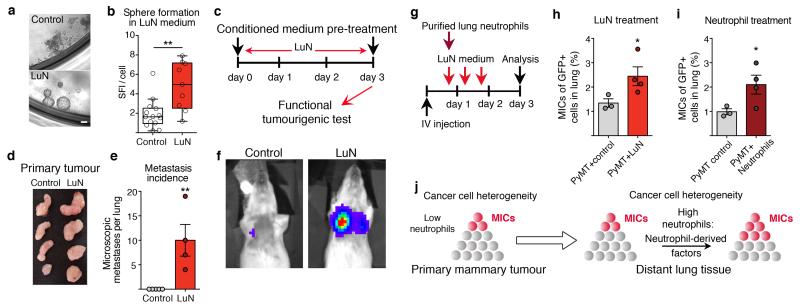

Next, we investigated a potential direct effect of neutrophil-secreted factors on tumour cells. Pre-metastatic lung neutrophils (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b) were used to condition cell culture medium for 14h (LuN medium). Primary MMTV-PyMT tumour cells cultured in LuN medium in non-adherent culture showed enhanced sphere growth (Fig. 2a,b). Furthermore, short-term exposure to LuN medium in adherent culture boosted tumorigenic potential of cancer cells in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). Importantly, short-term culture in LuN medium also increased the metastatic initiation potential of total cancer cells (Fig. 2e,f).

Figure 2. Neutrophil-derived signals promote tumorigenicity and increase the metastatic cell sub-pool.

a, b, Images and quantification (technical replicate n = 14 (control), n = 9 (LuN) of biological triplicates) of primary MMTV-PyMT spheres in indicated medium. SFI, sphere formation index. Scale bar, 10μm. c–f, Medium pre-treated luciferase+MMTV-PyMT cells (c) grafted onto the mammary gland (d) or intravenously injected (e, f) into Rag1-null mice. Lung metastases quantified by histological sectioning (n = 5 (control), n = 4 (LuN)). f, Representative bioluminescence signal. g, Experimental setup. h, i, Flow cytometric quantification of MICs in lungs of LuN-treated (n = 3 (PyMT control), n = 4 (PyMT+LuN)) (h) or neutrophil-treated mice (n = 3 (PyMT control) n = 4 (PyMT+neutrophils)) (i). j, Representation of cell heterogeneity change. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (b), Mann–Whitney test (e) and one representative experiment of two analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) (h, i). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Cancer cells are also heterogeneous when disseminated into the circulation15 and might respond differently to environmental stimulations16. We therefore probed whether neutrophil-secreted factors influence the relative amount of highly metastatic cells. We monitored the previously described MIC population (CD24+CD90+)8 after exposing tumour cells seeded into the lung to either LuN medium or freshly isolated pre-metastatic lung neutrophils (Fig. 2g). Notably, both settings induced a doubling of MIC frequencies among the total cancer cell population (Fig. 2h,i and Extended Data Fig. 6e-h) and partially increased metastatic growth (Extended Data Fig. 6i-k). Collectively, we observe that neutrophil-derived factors alter the heterogeneity of cancer cells favouring MICs and lead to increased metastatic competence of total cancer cells (Fig. 2j).

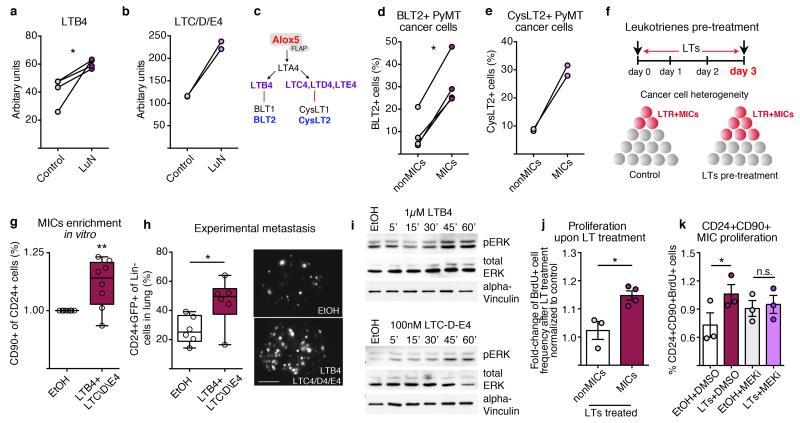

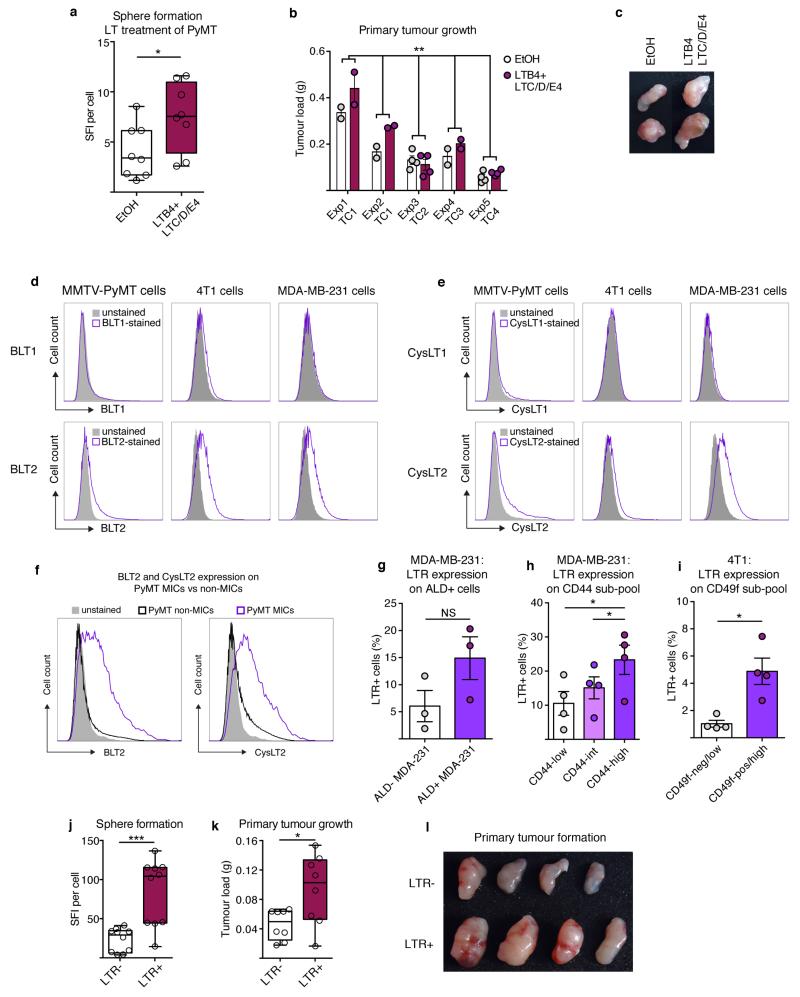

We aimed to identify neutrophil-secreted factors mediating this activity. LuN medium contains many factors (data not shown) including CCL2, MMP9, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1 that might alter inflammatory responses and increase pro-tumorigenic behaviour17-19. Various cells in the tumour microenvironment can secrete these mediators, so we concentrated on specific innate leukocyte-derived factors. We detected high levels of the lipids leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and cysteinyl leukotrienes C4, D4 and E4 (LTC/D/E4), products of the Alox5 enzyme20 (Fig. 3a-c). Importantly, direct leukotriene (LT) stimulation boosted sphere formation and a short 3-day LT-exposure of total cancer cells enhanced their tumour initiation potential (Extended Data Fig. 7a-c). Notably, cells expressing LT receptors (LTRs; LTB4 receptor 2 (BLT2) and LTC/E/D4 receptor 2 (CysLT2))21,22 appeared to be enriched among MICs within total MMTV-PyMT cancer cells as well as among known tumorigenic subpopulations of breast cancer cell lines23-25 (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 7d-i). Indeed, LTRs themselves identified MMTV-PyMT cancer cells with high sphere and tumour formation abilities (Extended Data Fig. 7j-l).

Figure 3. LTs enrich for MICs and tumorigenicity.

a, b, Enzyme immunoassay detecting LTB4 (n = 4 per group) (a) or LTC/D/E4 (n = 2 per group) (b). c, Overview of LTs and LTRs. d, e, Flow cytometric quantification of BLT2+ (n = 4 tumours) (d) and CysLT2+ cells (n = 2 tumours) (e) among indicated sub-pools. f–h, Representation of LT treatment (f): frequency of MICs (n = 8 per group) (g); and experimental lung metastasis (n = 6 per group) with representative images of GFP+ colonies. Scale bar, 3 mm. Lin, CD45 CD31 TER119. i, Western blot of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and total ERK1/2 levels of LTB4- or LTC/D/E4-treated cells for indicated minutes. Loading control: α -vinculin. j–k, 5-Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation comparing LT-treated MICs with non-MICs (n = 3 (non-MICs), n = 4 (MICs)) (j) or MICs treated with LTs and/or PD0325901 MEK inhibitor (MEKi; n = 3 per group) (k) DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide treated; EtOH, ethanol treated. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (a, d, h, j, k) and one-sample t-test (g). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Blot source data are in Supplementary Fig. 1.

In accordance with LTR expression on MICs, we found that 3-day LT stimulation of MMTV-PyMT tumour cells in vitro increased MIC frequency and metastatic initiation capacity in vivo (Fig. 3f-h), similar to neutrophil-derived mediators (Fig. 2g-j). LT stimulation also enriched the CD49fhigh sub-pool among 4T1 cells (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Other cells such as macrophages and eosinophils respond to LTs, but no broader inflammatory reaction was detected at this stage (Extended Data Fig. 4 and 5). In summary, LTs appear to shift heterogeneous cancer cell populations in favour of highly metastatic cells and enhance metastatic competence.

In line with previous reports on LTB4 signalling21,26, cancer cells responded to both LTB4 and LTC/D/E4, with increases in extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERK)1 and 2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 8c,d). LTR+ cells were required to detect a LT-dependent phosphorylated (p)ERK1/2 increase (Extended Data Fig. 8e-g) and inhibitors for BLT2 and CysLT2 interfered with ERK1/2 activation (Extended Data Fig. 8h-k). Finally, 3-day LTC/D/E4 treatment increased frequency of LTR+ cancer cells, suggesting a functional boost in proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 8l). Indeed, LT treatment specifically increased the proliferation of MICs in a MAPK/ERK kinases (MEK)1 and 2-mediated, pERK1/2-dependent manner (Fig. 3j,k and Extended Data Fig. 8m). These results indicate that LTs provide a selective proliferative advantage to cancer cells with intrinsically higher tumorigenicity (Extended Data Fig. 8a).

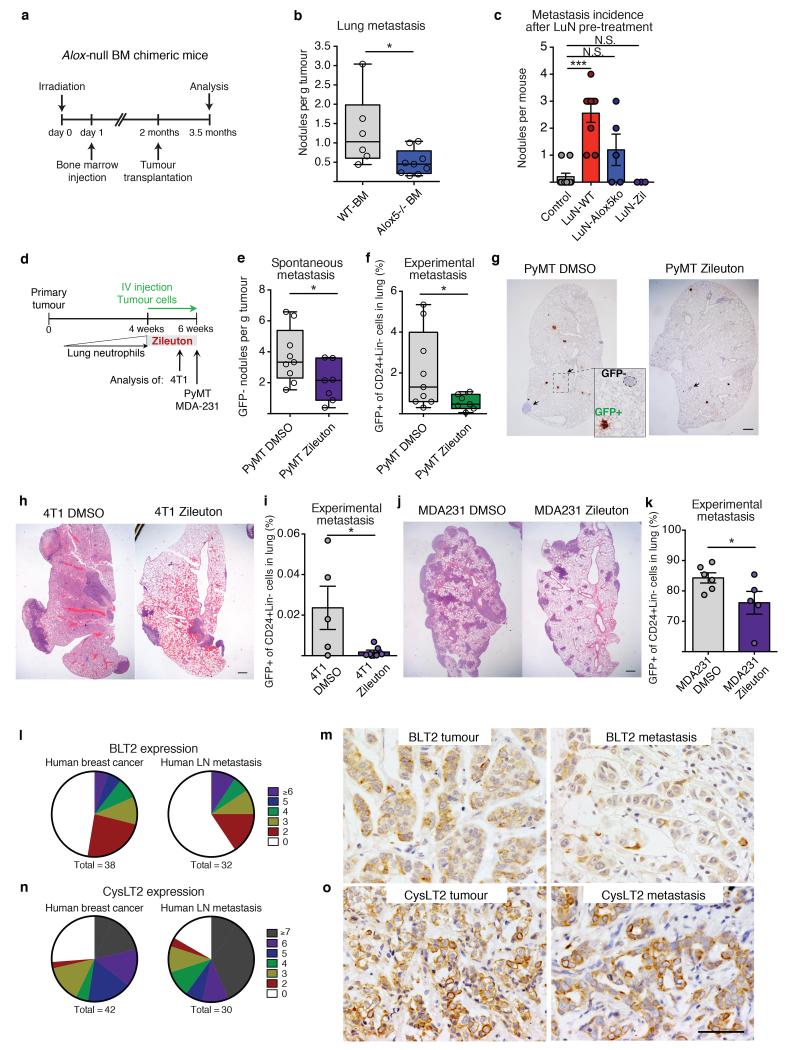

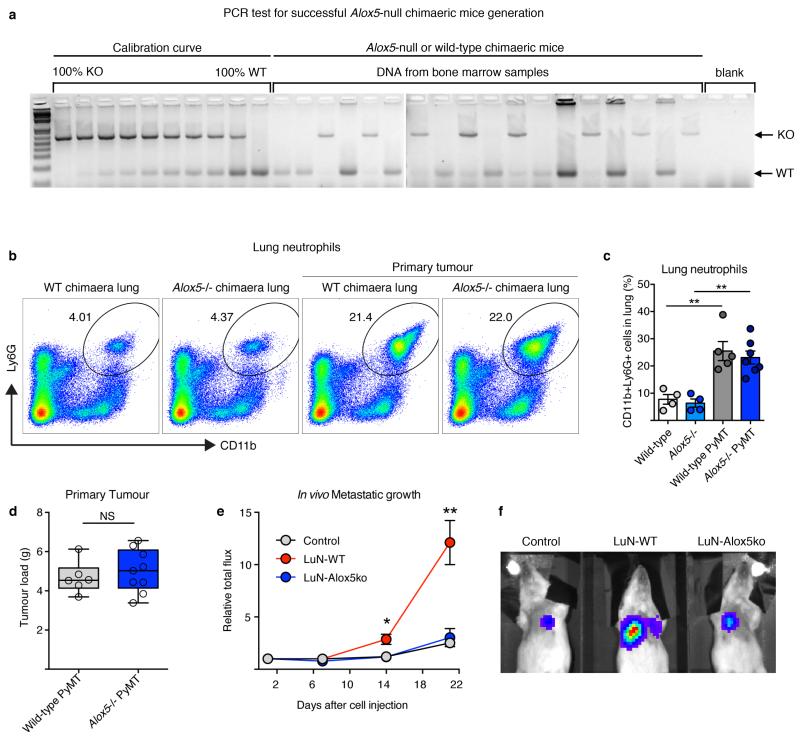

To confirm the functional relevance of LTs in vivo, we took advantage of an Alox5-null mouse model (Fig. 3c). We generated bone marrow chimaeric mice in which Alox5 is genetically depleted in the radiosensitive immune cell compartment. Bone marrow Alox5-null mice grafted with MMTV-PyMT cells showed unaltered primary tumour growth and neutrophil lung accumulation (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 9a-d), yet the efficiency of spontaneous metastasis was reduced (Fig. 4b). Next, we generated LT-deficient LuN (LuN-Alox5ko) medium from Alox5-null pre-metastatic lung neutrophils. Importantly, LuN-Alox5ko medium failed to boost the metastatic potential of luciferase-expressing MMTV-PyMT cells after 3-day pre-treatment (Fig. 2c, Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 9e,f). Taken together, these data confirm Alox5 products to be crucial for neutrophil pro-metastatic activity.

Figure 4. Alox5 inhibition decreases lung metastasis initiation.

a, b, Alox5-null bone marrow (BM) chimaera experimental setup (a) and spontaneous metastasis (n = 6 (wild-type bone marrow), n = 9 (Alox5−/− bone marrow)) (b). WT, wild-type. c, Surface metastases of medium pre-treated cancer cells (n = 10 (control), n = 9 (LuN wild-type), n = 5 (LuN Alox5ko), n = 3 (LuN-Zil)). d, Experimental setup for Zil treatment. e–k, Spontaneous (e) and experimental (f, i, k) metastasis of MMTVPyMT cells (n = 9 (PyMT DMSO), n = 7 (PyMT Zil)) (e–g), 4T1 cells (n = 5 (4T1 DMSO), n = 7 (4T1 Zil)) (h, i) or MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 6 (MDA231 DMSO), n = 5 (MDA231 Zil)) (j, k). Lin, CD45 CD31 TER119. Representative histological lung sections GFP stained with close-up on spontaneous (arrows) and experimental metastases (brown) (g) or H&E stained (h, k). Scale bars, 500μm. l–o, BLT2 (l, m) or CysLT2 (n, o) staining (brown) of human breast cancer and matched lymph node (LN) metastases (n ≥ 30 per group). Quantification of staining intensity and frequency (l, n) and representative images (m, o). Scale bar, 50μm. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (b, e, f, i), Mann–Whitney test (c) and one-sided t-test (k). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

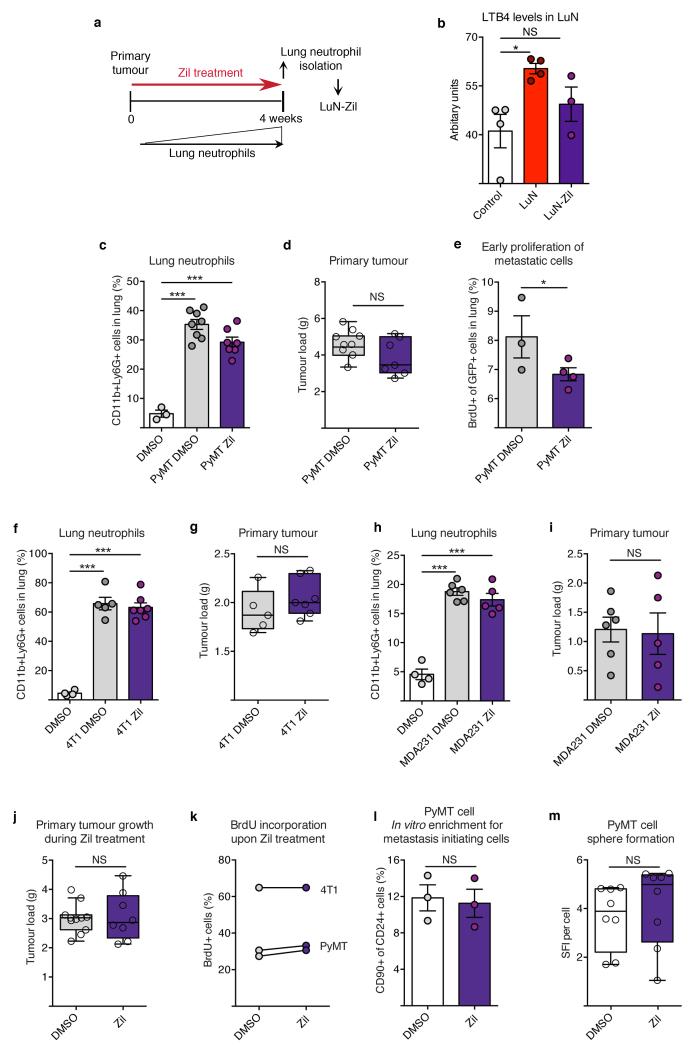

LTs are important mediators during inflammatory asthma and targeted by the specific Alox5 inhibitor zileuton (Zil)27. We explored Zil-mediated inhibition of LT synthesis to treat metastatic breast cancer in mice. Zil blocked LT production in vivo, detected by decreased LTB4 levels in LuN medium (LuN-Zil) (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b) and, consequently, LuN-Zil medium failed to enhance metastasis (Fig. 4c). Importantly, in a therapeutic setting (Fig. 4d), treatment of MMTV-PyMT tumour-harbouring mice with Zil reduced spontaneous metastasis (Fig. 4e,g), without altering primary tumours or lung neutrophil levels (Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). Additionally, colonization capacity of GFP+ MMTV-PyMT cancer cells seeded into lungs of Zil-treated mice was reduced (Fig. 4f,g). We confirmed that metastatic cancer cells showed reduced proliferation very early after infiltrating Zil-treated lungs (Extended Data Fig. 10e). Taken together, these data represent a potential therapeutic approach to target this novel LT/Alox5-dependet neutrophil pro-metastatic activity.

Importantly, similar results on the efficacy of Zil treatment in limiting metastatic progression were confirmed in two metastatic breast cancer cell lines, mouse 4T1 cells and human MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4h-k and Extended Data Fig. 10f-i). As Zil treatment had no effect on long-term primary tumour growth in vivo or on cancer cell behaviour in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 10j-m), we exclude involvement of Alox5 products in a cancer-cell autocrine loop.

Clinical data correlating high neutrophil levels with poorer prognosis28,29, together with detected LTR expression in human metastatic ductal and lobular breast carcinoma and their lymph-node metastases (Fig. 4l-o), suggests that a similar neutrophil pro-metastatic mechanism might boost human breast cancer progression to the lung.

We have identified a novel LT/Alox5-dependent pro-metastatic activity of neutrophils supporting highly metastatic cells that can be targeted by Zil, offering hope for new cancer therapeutics.

Methods

Mouse strains

The MMTV-PyMT mice were a gift from E. Sahai, MMTV-PyMT actin-GFP (mice expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of the actin promoter), Gcsf-null and Rag1-null mice were a gift from J. Huelsken, MMTV-PyMT actin-luciferase (mice expressing firefly luciferase under the control of the actin promoter) transgenic line was a gift from D. Bonnet, Rosa26R-eGFP-DTA mice were a gift from C. Reis e Sousa. Ela2-Cre knock-in mice and Alox5-null mice were purchased from European Mouse Mutant Archive (EMMA) and Jackson Laboratory, respectively. All mouse strains have been described previously30-37. All strains of mice were in >10 generations FVB/N and/or C57BL/6 background except Gcsf-null, Ela2-Cre and Rosa26R-eGFP-DTA mice that were used in mixed background with littermate controls. Female mice were used between 6–9 weeks of age, except spontaneous cancer models. Breeding and all animal procedures were performed in accordance with UK Home Office regulations under project license PPL/80/2531.

Mouse experiments

Where applicable, mice were anaesthetized with IsoFlo (isoflurane, Abbott Animal Health) and temporally treated with the analgesics Vetergesic (Alstoe Animal Health) and/or Rimadyl (Pfizer Animal Health). For tumour studies under the project licence PPL/80/2531, the overruling determinant was animal welfare. The National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Guidelines for the Welfare and Use of Animals in Cancer Research were followed. When assessing primary tumour growth, a mean diameter of 1.5 cm for single tumours was not exceeded. However, for multifocal disease such as MMTV-PyMT cancer, provided that there were no additional adverse welfare consequences for the animal, the total superficial tumour burden was allowed to exceed these dimensions when essential for the achievement of the scientific objective, namely spontaneous metastasis. Mice were monitored daily for signs of adverse effects. The source data for primary tumour growth are in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Tumour cell transplantations and induction of experimental metastasis

FVB/N wild-type mice were used for MMTV-PyMT tumour cell transplantations to isolate lung neutrophils. Rag1-null mice were used when using human or mouse GFP or luciferase-expressing tumour cells. Primary MMTV-PyMT, MMTV-PyMT actin-GFP or MMTV-PyMT actin-luciferase cells (105-106 cells per injection), the unmarked or stably mouse phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK) promoter-GFP-expressing mouse mammary cancer cell line 4T1 (105 cells per injection) and the unmarked or stably actin-GFP-expressing human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 (1-2×106 cells per injection) were used. For experimental metastasis, tumour cells were re-suspended in 100μl PBS and tail vein injected. For orthotopic transplantations, tumour cells were re-suspended in 50μl growth-factor-reduced Matrigel (Costar) and transplanted within the fourth mammary fat pad on both flanks (MMTV-PyMT and MDA-MB-231 cells) or one flank only (4T1 cells).

Neutrophilia and lung immune cell infiltration in MMTV-PyMT+ mice

MMTV-PyMT+mice that spontaneously developed a primary tumour and had visible lung metastasis were used to determine immune cell presence in the lung and neutrophil presence in other organs together with tumour-free littermate controls. For determination of timing and dynamics of lung infiltration by neutrophils and cancer cells, MMTV-PyMT+ mice harbouring 1.5-2 g spontaneously developed tumours were used. Neutrophil infiltration was quantified by flow cytometry and histological staining of lung sections for S100A9 and cancer cell presence by examination of six histological lung sections (100μm apart) for PyMT staining to confirm the pre-metastatic state. The timing of neutrophil infiltration into the pre-metastatic lung before cancer cells was confirmed in FVB/N wild-type mice carrying two primary tumours originating from orthotopic injection of primary MMTV-PyMT cancer cells and used for analysis (daily treated with anti-Ly6G or control IgG antibody starting 24 h before tumour cell implantation).

Analysis of MMTV-PyMT+ G-CSF and MMTV-PyMT+ Ela2-DTA mice

Mice were culled and analysed about 6 weeks after spontaneous primary tumour onset; no differences were observed in tumour onset among the different genotypes.

Treatments with neutrophil-blocking antibody anti-Ly6G or Zil

Rat anti-Ly6G antibody38,39 (12.5 μg/mouse; clone 1A8 from BioXcell) or rat IgG isotype control (provided by the Cell Services Unit of The Crick Institute) in 100μl saline were administered daily via intra-peritoneal injection. Zil (LKT Laboratories) dissolved in DMSO (Sigma) or DMSO alone was fed to mice by pipetting on the back of the tongue once a day at a dosage of 100μg Zil per g mouse weight.

Lung colonization by cancer cells after neutrophil depletion or Zil treatment

Rag1-null mice were orthotopically transplanted with unlabelled mammary tumour cells 4 weeks before labelled tumour cell injection via the tail vein (MMTV-PyMT and 4T1 105 cells, MDA-MB-231 106 cells). Anti-Ly6G or Zil treatment for 2 weeks (except 4T1, 10 days) started 1 day before intravenous injection of cancer cells. Then, total primary tumour burden, neutrophil presence in the lung, spontaneous lung metastasis incidence from the transplanted primary tumour and/or experimentally induced lung metastasis originating from the intravenously injected cancer cells was analysed.

Of note, exclusively experimental metastasis are present in lung harbouring MDA-MB-231 cells, while predominantly spontaneous metastases are visible in lung harbouring 4T1 cells due to the high spontaneous metastasis rate of primary 4T1 tumours. Only GFP+ experimental metastasis induced by cancer cell injection was quantified in these experiments.

Tumour/metastasis initiation potential assay in vivo

Primary MMTV-PyMT cells were either cell sorted for BLT2 and/or CysLT2 presence or absence, or treated for 3 days on collagen-coated dishes with either neutrophil-conditioned medium or LTB4 and LTC/D/E4. Subsequently, 103-104 cells were orthotopically transplanted into the mammary gland or 106 cells injected via the tail vein into Rag1-null mice and mammary tumour growth or lung metastasis incidence analysed about 3 weeks thereafter.

MIC or metastasis quantification after neutrophil/LuN injection

To analyse total cancer cells at early stages, Rag1-null mice were injected with 0.5-1×106 MMTV-PyMT actin-GFP cells via the tail vein followed 12 h later by intravenous injection of 25×106 neutrophils (freshly isolated from MMTV-PyMT tumour-transplanted mice) or 12, 24 and 36 h later by intravenous injection of 200μl lung neutrophil-conditioned or control sphere medium (described later). Cancer cells in the lung were analysed 3 days after the initial tumour cell injection for frequencies of CD90+ MICs among GFP+CD24+ (non-MIC) cancer cells. For determination of effects of neutrophils or neutrophil-conditioned medium on metastatic burden, Rag1-null mice were intravenously injected with 1-10×105 MMTV-PyMT actin-GFP or actin-luciferase cells followed immediately, 2 and 4 days later, by injection of 25×106 neutrophils or 3-5 times every 12 h by injection of 200μl lung neutrophil-conditioned medium. Metastatic burden was determined by flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ cancer cells 1 week or bioluminescence imaging of luciferase+ cancer cells 2-4 weeks thereafter, respectively.

Analysis of functional effects of G-CSF-deficiency in MMTV-PyMT cancer cells

Rag1-null mice were transplanted with 106 Gcsf-null primary MMTV-PyMT cancer cells into two mammary glands and tumour growth, spontaneous metastatic incidence and neutrophil presence in the lung were analysed 4 weeks thereafter.

Bone marrow transplantation and semi-quantitative PCR

C57BL/6 wild-type mice were lethally irradiated (dosage: 2× 600rad, 4 h apart) and 24 h later injected via the tail vein with 2×106 bone marrow cells freshly isolated from C57BL/6 or Alox5-null donor mice. Bone marrow chimaeric mice were orthotopically transplanted with 106 MMTV-PyMT cells into the fourth mammary fat pad on both sides 8 weeks after bone marrow reconstitution and primary tumour size, neutrophil infiltration into the lung and lung metastasis analysed 6 weeks later. Chimaeric mice were generated in a pure C57BL/6 background, therefore MMTV-PyMT cells from the same background were used to generate primary tumours. In this lower tumorigenic background, metastasis only occurs in about 50% of the mice. No alteration in this penetrance was observed between wild-type and Alox5-null BM chimaeric mice. Figure 4b quantifies animals harbouring metastatic disease.

Percentage of bone marrow reconstitution was calculated by isolating total DNA from bone marrow of chimaeras and semi-quantitative PCR with a calibration curve from 100% wild-type DNA mixed at defined ratios with 100% Alox5-null DNA. PCR was performed using Redtag reagents (Sigma) (primers are listed in Supplementary Information) and 25 amplification cycles before loading an agarose gel. Ratio between wild-type and Alox5-null band was calculated for every mouse and percentage chimaerism determined by comparison with calibration curve. Chimaerism was consistently between 80-96%.

Tumour and metastasis burden evaluation

In vivo luciferase-activity detection

Mice inoculated with actin-luciferase-expressing MMTV-PyMT cells were shaved around the chest area and injected with 3mg XenoLight D-luciferin potassium salt (PerkinElmer) in PBS into the peritoneum 5 min before imaging for at least 45 min using the IVIS Spectrum Pre-clinical In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer). The maximum bioluminescence intensity signal for the lung of every mouse was determined using Living Image 4.3.1 software.

Tissue staining, immunohistochemistry and light microscopy

Mouse lung tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h and embedded in paraffin blocks. Four-micrometre sections were stained. The breast cancer tissue array paired with metastatic tumours, 96 samples (1.5mm), was purchased from Abcam (ab178118). H&E staining was performed according to standard procedures.

For immunohistochemistry, either secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies were used in combination with DAP Peroxidase substrate or the VECTASTAIN ABC kit (all Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primary antibodies were used (see Supplementary Information), visualization of cell nuclei was performed with haematoxylin and analysis employed the Nikon Eclipse 90i light microscope and NIS-elements software.

Scoring of LTR expression in breast cancer tissue and lymph node metastasis

Tissue digestion for cell isolation or analysis

MMTV-PyMT cell isolation was described in detail previously8. In brief, primary MMTV-PyMT tumours, liver, spleen and lung were dissected, minced, digested with Liberase (Roche) and DNaseI (Sigma) in HBSS and passed through a 100μm cell strainer. Some tumour cells were used for cell culture at this point. Bone marrow cells were isolated by crushing the femur and tibia and blood collected via bleeding from the tail vein with Heparin (Sigma) as a coagulant. For flow cytometric analysis or further purification, single cell suspensions of tumour, liver, spleen, lung, bone marrow and blood were subjected to hypotonic lysis (Red Blood Cell Lysis Solution, Miltenyi) to remove erythrocytes and washed with 1×PBS/2mM EDTA/0.5% BSA.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Prepared single cell suspensions of mouse tissues and in vitro treated cancer cells were incubated with mouse FcR Blocking Reagent (Miltenyi) followed by incubation with (a combination) of specific pre-labelled antibodies or in combination with fluorescently-labelled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) (see Supplementary Information). Dead cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or propidium iodide (PI; both Sigma). The LSRFortessa cell analyser running FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software was used. Tumour cells were flow-sorted using the Influx cell sorter running FACS Sortware sorter software (BD Biosciences). MMTV-PyMT cells were used in experiments immediately after sorting and sorted 4T1 cells cultured in adherent conditions for 3 days prior to western blot analysis.

Neutrophil isolation and neutrophil-conditioned medium

Freshly isolated lung cells from wild-type mice orthotopically transplanted with MMTV-PyMT tumours were incubated with mouse FcR Blocking Reagent (Miltenyi), APC-coupled anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8) antibody (BD Bioscience) followed by incubation with magnetic anti-APC microbeads (Miltenyi). Magnetically labelled neutrophils were isolated using LS columns (Miltenyi) according to manufacturers instructions. Neutrophil purity and viability was measured by flow cytometry. Some isolated Ly6G+ cells were smeared onto a glass slide and air-dried overnight followed by H&E staining to evaluate cell morphology. Remaining neutrophils were kept in sphere medium at a concentration of 106 neutrophils per 150μl medium for 14 h to allow conditioning. Neutrophils and cell debris were removed by centrifugation and conditioned medium occasionally snap-frozen before use.

Cell culture and in vitro cancer cell treatments

All used cell lines were provided by the Cell Services Unit of The Crick Institute, which routinely tests for Mycoplasma contamination and were not further authenticated in our laboratory. Cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (DMEM/FCS, both Invitrogen). Freshly isolated MMTV-PyMT cells were cultured overnight on PureCol collagen (Advanced Biomatrix)-coated dishes in growth medium DMEM/F12 with 2% FBS, 20 ng ml−1 EGF (Invitrogen) and 10 μg ml−1 insulin (Sigma) before use in experiments. All in vitro and in vivo experiments involving primary MMTV-PyMT cells were performed with at least two primary tumour cell preparations from different spontaneous MMTV-PyMT+ mice. Unless otherwise specified, each in vitro and in vivo experiment was performed with a different tumour cell preparation.

Primary MMTV-PyMT cells were cultured in sphere medium on collagen-coated dishes, 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells in DMEM/FCS on uncoated dishes or in non-attachment conditions for the indicated periods of time under presence of (as indicated for every experiment): control sphere medium, neutrophil-conditioned medium, 100% ethanol control (EtOH, Sigma), DMSO control, 1μM LTB4, 100nM LTC/D/E4 (Cysteinyl Leukotriene HPLC Mixture I), 3μM BLT2 inhibitor LY255283, 0.3μM CysLT2 inhibitor BAY-u9773 (all Cayman Chemical), 1μM Zil and/or 1nM pan-MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (provided by J. Downward) followed by further tests or analysis.

Sphere formation assay

The sphere formation assay was described previously8. In brief, 104 total MMTV-PyMT or flow-sorted cells per well were plated in ultra-low-attachment 96-well plates (Costar) in 100μl sphere medium DMEM/F12 supplemented with B-27, 20 ng ml−1 EGF, 20 ng ml−1 FGF (all Invitrogen) and 4 μg ml−1 heparin (Sigma) or neutrophil-conditioned medium. After 7-10 days, if not otherwise indicated, all formed spheres were quantified from images taken with the inverted Leica DM IRBE light and fluorescence microscope. The area of the plane passing through the sphere-centre was measured for every sphere (sphere size) using ImageJ software and the areas of all formed spheres were summed up. The obtained number was divided by total number of plated cells. This value represents the sphere formation index (SFI) per cell for every experimental group. Freshly isolated MMTV-PyMT cells were either only treated for 3 days in adherent conditions before sphere assay or directly treated during the sphere assay with neutrophil-conditioned medium or LTB4 and/or LTC/D/E4 or Zil, as indicated. When cells were passaged, cells were quantified by cell counting and re-plated in equal numbers per well for the next passage approximately every 7 to 10 days.

In vitro and in vivo BrdU incorporation assay

Rag1-null mice carrying MMTV-PyMT tumours were treated daily for 3 days with Zil and intravenously injected with 105 GFP-expressing MMTV-PyMT cancer cells. BrdU (1mg per mouse) was intraperitoneally injected 18 h after GFP+ cancer cells and lungs harvested and digested 6 h later. In vitro 3-day MMTV-PyMT or 4T1 cells treated as indicated in adherent conditions were pulsed with 30μM BrdU (Sigma) for 3 hours and harvested. Cells were incubated with fluorescently labelled anti-CD24 and/or anti-CD90.1 antibody if indicated. BrdU Flow Kit (BD Bioscience) was used for staining followed by analysis by flow cytometry.

In vitro quantification of primary MICs and sub-pools of cancer cell lines

Primary MMTV-PyMT cells were cultured on collagen-coated dishes for 3 days supplemented with either LTB4 and LTC/D/E4 or Zil followed by incubation with fluorescently labelled anti-CD90.1 and anti-CD24 antibodies and analysis by flow cytometry. 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were cultured in DMEM/FCS supplemented with LTB4 and LTC/D/E4 for 3 days in adherent conditions followed by either staining with fluorescently labelled anti-CD49f, anti-BLT2, anti-CysLT2 and/or anti-CD44 antibodies or using the ALDEFLUOR kit (Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and analysed by flow cytometry.

RNA expression/quantitative real-time PCR

Neutrophils were freshly isolated from the lungs of wild-type or MMTV-PyMT tumour-bearing mice. RNA isolation was performed using MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit and cDNA synthesis using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase. Quantitative PCR reactions were performed using EXPRESS SYBR GreenER reagents with the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (all Invitrogen) and specific primers (see Supplementary Information).

Enzyme immunoassay and parameter enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Ethanol was used to precipitate protein from cell culture medium before analysis using either the enzyme immuno-assays (EIAs) LTC/D/E4 Biotrak EIA System (Amersham) or the LTB4 EIA Kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis and protein detection

Primary MMTV-PyMT cells grown on collagen-coated dishes were cultured overnight in DMEM/F12 with B-27, and 4 μg ml−1 heparin (Sigma) before treatment with 1μM LTB4 or 100nM LTC/D/E4. Unsorted or sorted LTR-reduced 4T1 cells were stimulated with LTB4, LTC/D/E4, BLT2 inhibitor LY255283 and/or CysLT2 inhibitor BAY-u9773 as indicated. Cells were washed and protein isolated using RIPA buffer (25mM Tris-hydrogen chloride pH7.6, 50mM sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% soduim dodecyl sulphate) freshly supplemented with 1μM sodium pyrophosphate, 1μM B-glycerophosphate, 1μM sodium vanadiumoxide, 1μM sodium fluoride, 1μM sodium molybdate (all Sigma) and cOmplete ULTRA Tablets (Roche), and processed by standard western blot techniques. Membranes were blocked with 5%BSA in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma) and incubated with specific primary antibodies (see Supplementary Information). ECL Western Blotting System including secondary antibodies and Hyperfilm ECL (both Amersham) were used. Protein lysates of 3 h LTB4-stimulated MDA-MB-231 cells were analysed using the Proteome Profiler Human Phospho-Kinase Array Kit (R&D systems) according to themanufacturer’s instructions. Western blot quantification was performed on scanned films using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses used GraphPad Prism version 7. The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean, individual values, “scatter plot with Tukey box & whiskers” and/or “scatter plot with column bar” graphs and were analysed using Student’s t-tests (paired or unpaired according to the experimental setting), Mann-Whitney tests, one-sample t-tests and two-way ANOVA as indicated in the legends. Data were pooled from at least two experiments, except Fig. 4c,i,k and Extended Data Figs 2d, 4d-m, 5a,b,f,h, 6k, 10e in which data are at least biological triplicates generated in parallel. Two-way ANOVA was performed when the control groups between experiments were significantly different. Western blot in Extended Data Fig. 8i,k, the Proteome Profiler dot blot in Extended Data Fig. 8d and BrdU incorporation of 4T1 cells in Extended Data Fig. 10k were performed once. Extended Data Fig. 3b (mRNA expression) compares biological triplicates of the pre-metastatic to a representative control (wild-type) value. The experiments were not randomized and there was no blinding as animals or samples were marked. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes. Sample sizes were based on previous experience with the models8,14. n values represent biological replicates, with the exception of the sphere assays, for which both technical and biological replicates are shown. Differences were considered significant when P<0.05 and are indicated as NS, not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data

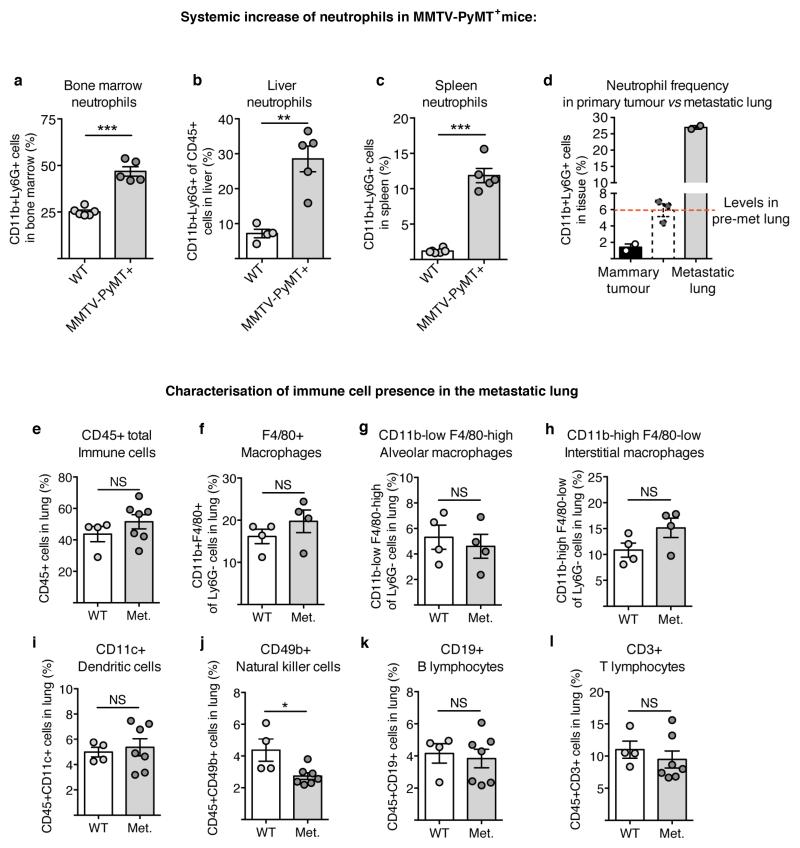

Extended Data Figure 1. Mammary tumour-bearing MMTV-PyMT+ mice show specifically neutrophilia in the metastatic lung.

a–c, Flow cytometric quantification of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in the bone marrow (n = 6 (wild-type), n = 5 (MMTV-PyMT+)) (a), liver (n = 4 (wild-type), n = 5 (MMTV-PyMT+)) (b) and spleen (n = 6 (wild-type), n = 5 (MMTV-PyMT+)) (c) of wild-type (WT) and tumour-bearing MMTV-PyMT+ mice. d, Quantification of neutrophils in the tumour and metastatic lung of MMTV-PyMT+ mice (n = 2 per group), pre-metastatic lung neutrophil levels depicted in Fig. 1a are shown for comparison in dashed lines. Met., metastatic. e–l, Flow cytometric quantification of immune cell frequencies in wild-type and metastatic lungs of MMTV-PyMT+ mice (n = 4 (wild-type), n = 7 (metastatic) if not otherwise indicated) including CD45+ total immune cells (e), total CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages (f) (n = 4 (wild-type), n = 4 (metastatic)), the CD11blow F4/80high alveolar macrophage subpopulation (n = 4 (wild-type), n = 4 (metastatic)) (g), the CD11bhigh F4/80low interstitial macrophage subpopulation (n = 4 (wild-type), n = 4 (metastatic)) (h), CD45+CD11c+ dendritic cells (i), CD45+CD49b+ NK cells (j), CD45+CD19+ B lymphocytes (k) and CD45+CD3+ T lymphocytes (l). Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

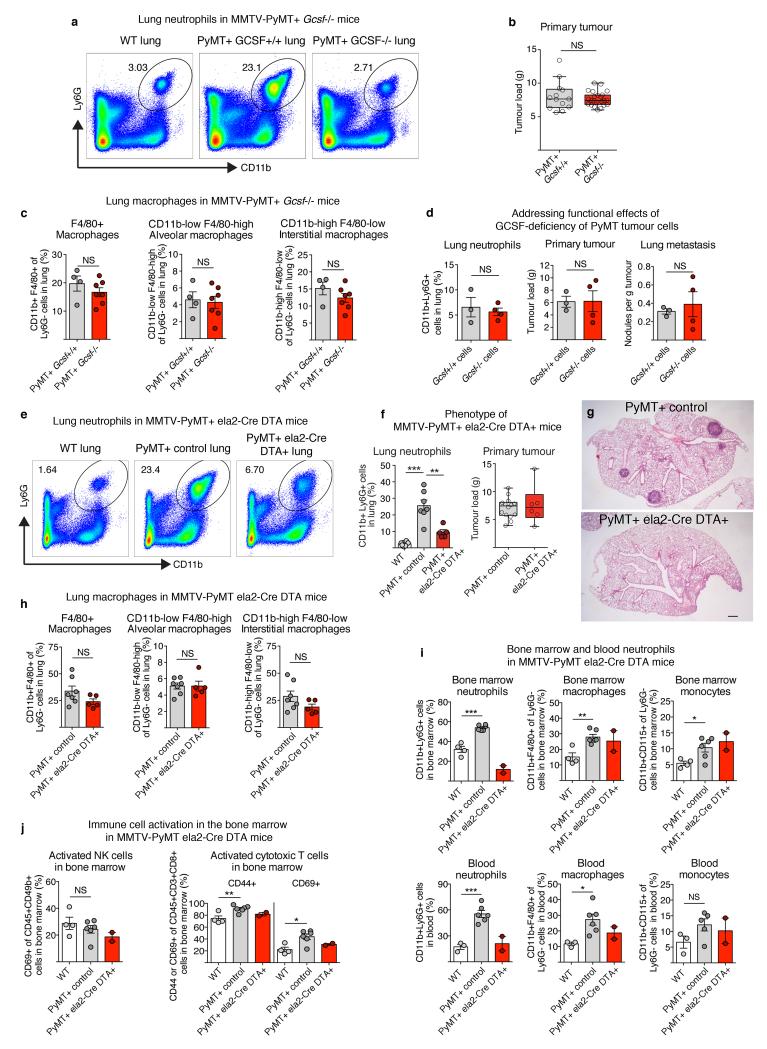

Extended Data Figure 2. Analysis of MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf−/− mice, G-CSF-deficient MMTV-PyMT cancer cells and MMTV-PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+ mice.

a, Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in the lung of wild-type and tumour-bearing MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf+/+ and MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf−/− mice. b, Primary mammary tumour burden of MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf+/+ (n = 13) or MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf−/− (n = 24) mice. c, Flow cytometric quantification of frequencies of total CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages (left), the CD11blowF4/80high alveolar macrophage subpopulation (middle) and the CD11bhighF4/80low interstitial macrophage subpopulation (right) in the lung of tumour-bearing MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf+/+ (n = 4) and MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf−/− (n = 7) mice. d, MMTV-PyMT+Gcsf−/− primary cancer cells were freshly isolated and grafted onto two mammary glands of Rag1-null mice (106 cells per injection) and analysed 5 weeks thereafter. CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophil presence in the lung was assessed by flow cytometry (left), primary tumour burden was assessed by weighing (middle) and spontaneous lung metastasis incidence was assessed by quantification of visible surface lung metastases relative to tumour load (right) (n = 3 (Gcsf+/+), n = 4 (Gcsf−/−)). e–g, Analysis of tumour-bearing MMTV-PyMT+ control and MMTV-PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+ mice. Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in the lung (e). Lung neutrophil quantification (n = 8 (wild-type), n = 7 (PyMT+ control), n = 5 (PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+)) (f, left) and primary mammary tumour burden (n = 14 (PyMT+ control), n = 6 (PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+)) (f, right) with representative H&E-stained histological lung sections (g). Scale bar, 500μm. h, Flow cytometric quantification of frequencies of total CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages (left), the CD11blowF4/80high alveolar macrophage subpopulation (middle) and the CD11bhighF4/80low interstitial macrophage subpopulation (right) in the lung of tumour-bearing MMTV-PyMT+ control (n = 7) and MMTVPyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+ (n = 5) mice. i, Frequencies of bone marrow (top) and blood (bottom) CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils (left; blood n = 3 (wild-type), n = 6 (PyMT+ control)), CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages (middle; blood n = 3 (wild-type), n = 6 (PyMT+ control)) and CD11b+CD115+ monocytes (right; blood n = 3 (wild-type), n = 5 (PyMT+ control)) in wild-type, MMTV-PyMT+ control and MMTV-PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+ mice analysed by flow cytometry (n = 4 (wild type), n = 6 (PyMT+ control), n = 2 (PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+) if not otherwise indicated). j, Exclusion of immune responses against DTA expression in the bone marrow by analysis of NK-cell (left) and cytotoxic T-cell (right) activation. Flow cytometric quantification of activated CD69+ among total CD45+CD49b+ NK cells as well as activated CD44+ or CD69+ among total CD45+CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the bone marrow of wild-type (n = 4), MMTV-PyMT+ control (n = 6) and MMTV-PyMT+Ela2-Cre-DTA+ (n = 2) mice. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

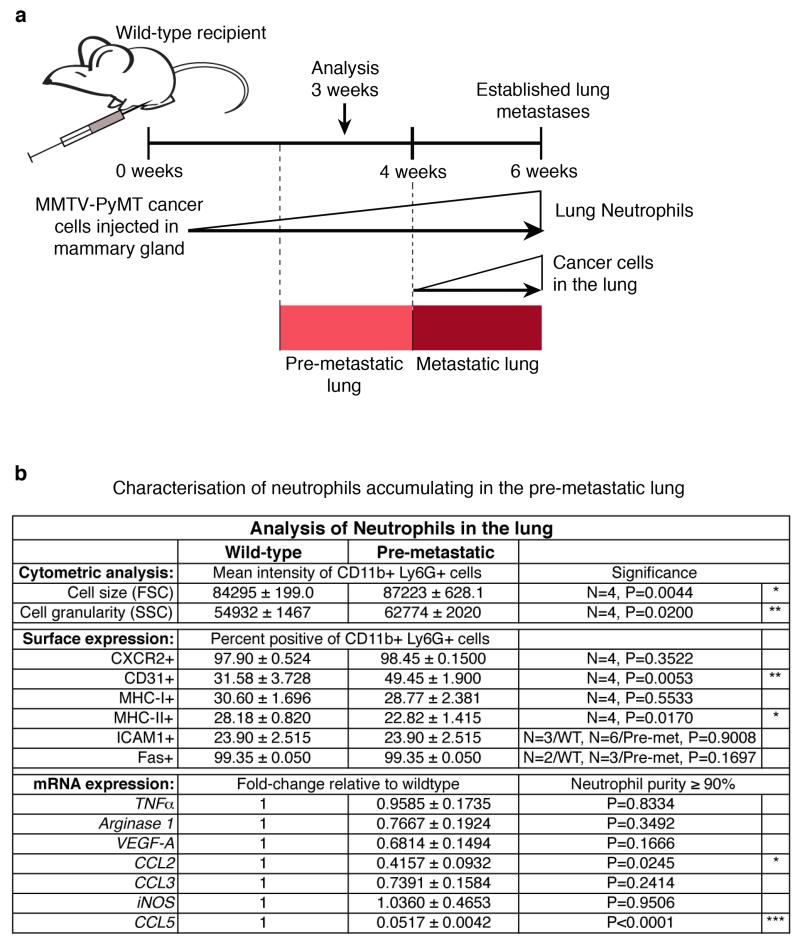

Extended Data Figure 3. Comparison of wild-type lung neutrophils with tumour-induced, pre-metastatic lung neutrophils.

a, Representation of timing and dynamics of neutrophil and cancer cell infiltration into the lung of mice grafted with two mammary tumours by orthotopic injection of 106 MMTV-PyMT tumour cells. b, Flow cytometric analysis for cell size (forward scatter (FSC)), granularity (side scatter (SSC)) and expression of surface markers CXCR2, CD31, MHC-I, MHC-II, ICAM1 and Fas (n is indicated) as well as mRNA expression analysis of Tnfa, arginase 1, Vegfa, Ccl2, Ccl3, iNOS (also known as Nos2) and Ccl5 by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of CD11b+Ly6G+ wild-type (WT) or pre-metastatic (Pre-met.) lung neutrophils 3 weeks after primary tumour graft (n = 3 (pre-metastatic compared with one normal lung reference)). Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (flow cytometry) and one-sample t-test (mRNA). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

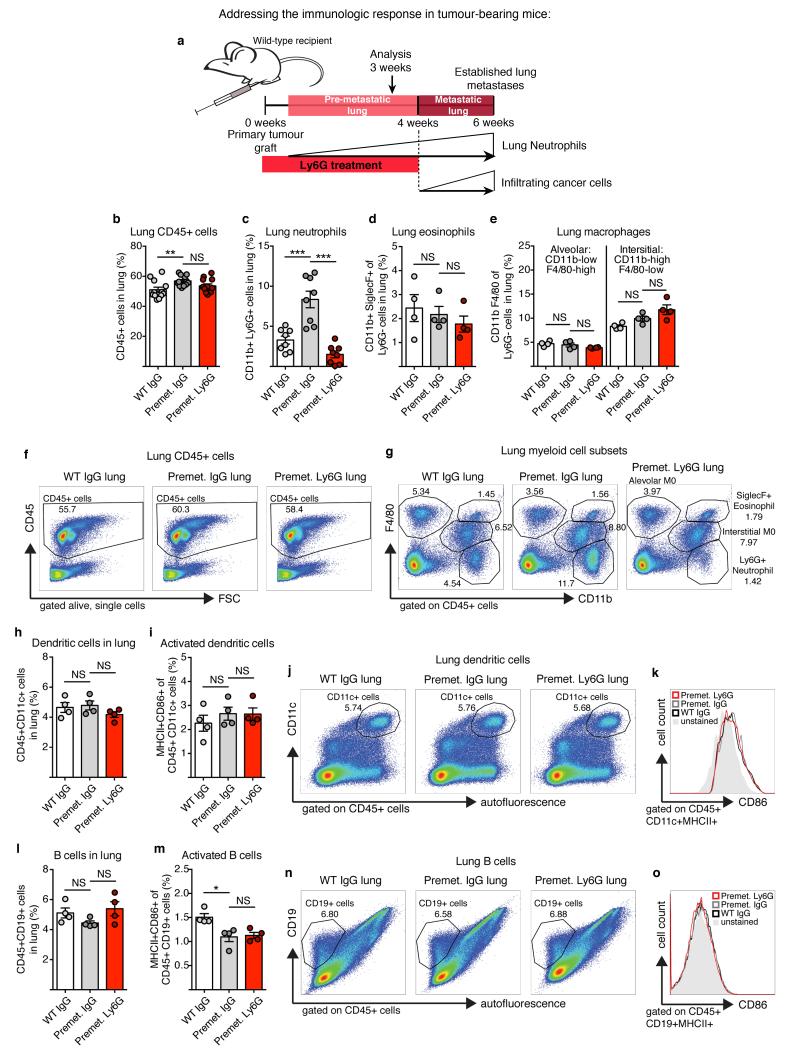

Extended Data Figure 4. Immune cell frequencies and activation in the pre-metastatic lung of MMTV-PyMT tumour-bearing mice is not dependent on neutrophil presence (part 1).

a, Representation of timing and dynamics of neutrophil and cancer cell infiltration into the lung of mice grafted with two mammary tumours by orthotopic injection of 106 MMTV-PyMT tumour cells. b–o, Flow cytometric quantification and representative analysis of the following immune cell types in wild-type (WT) or pre-metastatic (Pre-met.) lungs treated daily with either control IgG or anti-Ly6G (1A8) neutrophil-blocking antibody from tumour onset onwards (n = 4 per group if not otherwise indicated): b, f, total CD45+ immune cells (n = 12 per group); c, g, CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils (n = 8 per group); d, g, CD11b+SiglecF+ eosinophils; e, g, CD11blowF4/80high alveolar macrophages and CD11bhighF4/80low interstitial macrophages; h, j, CD45+CD11c+ dendritic cells; i, k, MHC-II+CD86+ activated dendritic cells; l, n, CD45+CD19+ B cells; and m, o, MHC-II+CD86+ activated B cells. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Extended Data Figure 5. Immune cell frequencies and activation in the pre-metastatic lung of MMTV-PyMT tumour-bearing mice is not dependent on neutrophil presence (part 2).

a–i, Flow cytometric quantification and representative analysis of the following immune cell types in wild-type (WT) or pre-metastatic (Pre-met.) lungs treated daily with either control IgG or anti-Ly6G (1A8) neutrophil-blocking antibody from tumour onset onwards (n = 4 per group if not otherwise indicated): a, c, CD45+CD49b+ NK cells; b, c, CD69+ activated NK cells; d, e, CD45+CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (n = 8 per group); f, g, CD44+ or CD69+ activated T cells; and h, i, the ratio of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells per activated T cell. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant.

Extended Data Figure 6. Neutrophil isolation from the lung of MMTVPyMT+ mice and effect of neutrophil-derived factors on tumour formation potential.

a, Representative flow cytometric analysis of neutrophil purity after isolation from the pre-metastatic lung compared to total lung tissue. Only neutrophil purity of ≥90% was used for further experiments. b, Neutrophil viability was assessed by flow cytometry for propidium iodide (PI) negativity after isolation (n = 10). c, d, MMTVPyMT cells grown in control or LuN medium for 3 days in adherent conditions were plated in non-attachment conditions followed by sphere quantification at day 10 post-seeding (technical replicate n = 17 (control), n = 21 (LuN) of biological triplicates) (c) or 104 cells grafted onto the mammary gland of Rag1-null mice for analysis of tumour formation potential (d). Tumour burden was determined by weighing about 3 weeks after (n = 12 per group), complementary to Fig. 2d. e–h, Flow cytometric quantification of frequencies of total present GFP-labelled MMTV-PyMT cells (e, g) and frequencies of CD24+CD90+ MICs among total GFP-labelled MMTV-PyMT cells (f, h) in the lung of Rag1-null mice 3 days after intravenous injection of 5×105 total GFP-labelled MMTV-PyMT cells followed by either three intravenous injections with control or LuN medium (n = 6 (PyMT+control), n = 8 (PyMT+LuN)) (e, f) or by one intravenous injection with 25×106 neutrophils freshly isolated from a pre-metastatic lung (n = 7 (PyMT control), n = 8 (PyMT+neutrophils) (g, h). f, h, Two independent experiments are shown to complement Fig. 2h, i. Exp, experiment. i–k, Experimental setup (i): Rag1-null mice were intravenously injected with 1–10×105 (j) or 0.5×106 total GFP-labelled MMTV-PyMT cells (k) followed by either 3-5 intravenous injections with 200μl control or LuN medium (j) or by three intravenous injections with 25×106 neutrophils (k) freshly isolated from a pre-metastatic lung. Quantification of experimental metastatic incidence by determination of bioluminescence intensity (n = 7 (control), n = 9 (LuN)) (j) or flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ cancer cells in the lung (n = 5 (control), n = 4 (neutrophil)) (k) is shown. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (c, j, k) and two-way ANOVA (d–h). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Extended Data Figure 7. LTRs are expressed on mouse and human breast cancer cells and enriched on metastasis-initiating and highly tumorigenic cancer cell sub-pools.

a, Sphere formation potential of MMTV-PyMT cells under presence of LTB4 or LTC/D/E4 (technical replicate n = 8 per group of biological triplicates). b, c, Three-day LTB4 and LTC/D/E4-treated MMTVPyMT cells in adherent culture were analysed for primary tumour initiation potential by orthotopic transplantation of 104 cells in Rag1-null mice (n = 14 per group) (b). Exp, experiment; TC, tumour cell isolation. Representative image of tumours is shown (c). d, e, Flow cytometric analysis of primary MMTV-PyMT cancer cells, the mouse mammary cancer cell line 4T1 and the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 for expression of BLT1 or BLT2 (d) as well as CysLT1 or CysLT2 (e). f, Representative flow cytometric analysis of BLT2+ and CysLT2+ cells among MMTV-PyMT non-MICs and MICs. g–i, Flow cytometric quantification of LTR expression on Aldefluor (ALD)+ (n = 3 per group) (g) or CD44high MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 4 per group) (h) as well as CD49f+/high 4T1 cells (n = 4 per group) (i). j–l, Sorted LTR+ or LTR− MMTV-PyMT tumour cells were plated in non-attachment conditions followed by sphere quantification at day 10 post-seeding (technical replicate n = 10 per group of biological duplicates) (j) or 103 cells grafted onto the mammary gland of Rag1-null mice for analysis of tumour formation potential. Tumour burden was determined by weighing (n = 8 per group) after 3 weeks (k) and representative image of tumours is shown (l). Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (a, h–k) and two-way ANOVA (b). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

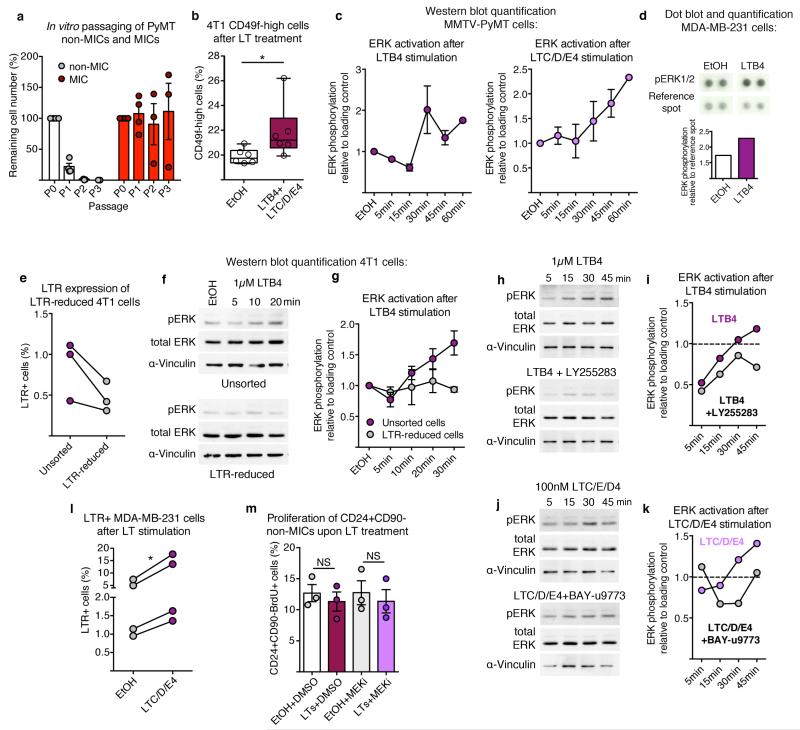

Extended Data Figure 8. LTs promote stemness within the total cancer cell population by specifically promoting proliferation of MICs.

a, In vitro passaging (P indicates passage number) in non-adherent conditions of sorted CD24+CD90+ MICs and CD24+CD90− non-MICs (n = 4 per group for P0+P1 and n = 3 per group for P2+P3). Quantification was performed by determination of percentage of remaining cell number after 7–10 days. b, Flow cytometric quantification of 3-day LT-treated 4T1 cells for frequency of highly tumorigenic CD49fhigh cells (n = 6). c, Quantification of western blots for ERK1/2 phosphorylation of MMTV-PyMT cells following LTB4 (left) or LTC/D/E4 (right) stimulation relative to α-vinculin as shown in Fig. 3i (n = 2 per time point except n = 9 (30 min LTB4)). d, Dot blot and quantification of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 cells after 3 h stimulation with LTB4 measured by R&D Proteome Profiler Human Phospho-Kinase Array (ARY003B; one-membrane array). e, Flow cytometric quantification of LTR expression of sorted LTR-reduced 4T1 cells (n = 3 per group). f, g, Representative analysis and quantification of western blots for total ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation relative to α-vinculin of unsorted 4T1 cells or 4T1 cells sorted for LTR negativity (n = 2 per group). h–k, Analysis and quantification of western blot for total ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation relative to α-vinculin of 4T1 cells following LTB4 (h, i) or LTC/D/E4 (j, k) stimulation in the presence of BLT2 inhibitor LY255283 or CysLT2 inhibitor BAY-u9773, respectively (one time series). Dotted lines in indicate the control level of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The decrease of ERK1/2 phosphorylation observed after 5–15 min when adding both leukotrienes and their receptor inhibitors is due to the increase in ethanol concentration. Data are shown as ERK1/2 phosphorylation recovery and increase from 5 to 45 min after stimulation (i, k). l, Flow cytometric quantification of 3-day LTC/D/E4-treated MDA-MB-231 cells for frequency of LTR+ cells (n = 4 per group). m, Three-day LT-treated MMTV-PyMT cells in adherent culture were analysed for BrdU incorporation of CD24+CD90− non-MICs in the additional presence of PD0325901 MEK inhibitor (MEKi; n = 3 per group). DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide treated; EtOH, ethanol treated. Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (l, m) and one-sided t-test (b). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05. Blot source data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Extended Data Figure 9. Analysis of Alox5-null bone marrow chimaeric mice transplanted with primary mammary MMTV-PyMT tumours and failure of Alox5-null neutrophils to support cancer cell metastatic initiation potential.

a, Efficiency of chimaeric mice generation was determined by semi-quantitative PCR analysis of DNA isolated from the bone marrow of lethally irradiated wild-type mice reconstituted with wild-type or Alox5-null bone marrow. A calibration curve of the ratio between the PCR band amplified from the wild-type (WT) and Alox5-null (KO) allele was used to calculate the percentage of bone marrow reconstitution efficiency. Tests of 8 representative Alox5−/− chimaeric mice and 10 controls are shown. Only mice with >80% Alox5-null bone marrow reconstitution were used for further experiments. b–d, Analysis of wild-type and Alox5-null bone marrow chimaeric mice 1.5 months after transplantation with 2 mammary MMTV-PyMT tumours (106 PyMT cells) or tumour-free controls. Representative flow cytometric analysis (b) and quantification of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophil presence in the lung (c) (n = 4 (wild-type), n = 4 (Alox5−/−), n = 5 (wild-type PyMT), n = 7 (Alox5−/− PyMT) as well as primary mammary tumour burden (n = 6 (wild-type PyMT), n = 9 (Alox5−/− PyMT)) (d). e, f, 5×105 luciferase-expressing MMTV-PyMT cells treated with control, wild-type LuN (LuN-WT) or Alox5-deficient neutrophil-derived LuN (LuN-Alox5ko) medium for 3 days in adherent culture were intravenously injected into Rag1-null mice. Quantification of cancer-cell-derived bioluminescence in the lung over time (n = 5 (control), n = 5 (LuN-WT), n = 4 (LuNAlox5ko)) (e) and representative image is shown (f). Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Blot source data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Extended Data Figure 10. Breast cancer cell growth, proliferation and self-renewal are not directly affected by treatment with the Alox5 inhibitor Zil.

a, b, Neutrophils were isolated from the lungs of MMTVPyMT mammary tumour-bearing mice treated daily with Zil and used to condition culture medium (LuN-Zil) (a). Enzyme-immunoassay analysis of LTB4 levels in control, LuN or LuN-Zil medium (n = 4 (control), n = 4 (LuN), n = 3 (LuN-Zil)) (b). c, d, f–i, Analysis of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in the lung by flow cytometry (c, f, h) and primary tumour burden (d, g, i) at the time of analysis of Rag1-null mice orthotopically transplanted and intravenously injected with GFP-labelled 105 primary MMTV-PyMT cancer cells (n = 3 (DMSO), n = 9 (PyMT DMSO), n = 7 (PyMT Zil)) (c, d), 105 mouse 4T1 cancer cells (n = 4 (DMSO), n = 5 (4T1 DMSO), n = 7 (4T1 Zil)) (f, g) or 106 human MDA-MB-231 cancer cells (n = 4 (DMSO), n = 6 (MDA231 DMSO), n = 5 (MDA231 Zil)) (h, i), and treated with Zil to complement Fig. 4d–k. e, Determination of in vivo cancer cell proliferation 18 h after intravenous injection of 105 GFP-labelled MMTV-PyMT cancer cells into MMTV-PyMT tumour-bearing, Zil-treated mice by 6 h BrdU pulse and flow cytometric quantification of BrdU+ among GFP+ cancer cells in the lung (n = 3 (PyMT DMSO), n = 4 (PyMT Zil). j, Quantification of mammary tumour load of control (DMSO) or Zil-treated wild-type mice 4–6 weeks after orthotopic transplantation with 106 MMTV-PyMT cells onto the mammary gland. Daily Zil treatment started 1 day prior to mammary tumour engraftment (n = 11 (DMSO), n = 8 (Zil)). k, Flow cytometric quantification of BrdU incorporation after a 3 h pulse of two primary MMTV-PyMT cell preparations and one culture of the mouse 4T1 cell line treated with 1μM Zil for 24 h in adherent conditions. l, Flow cytometric quantification of frequency of CD24+CD90+ MICs in total MMTV-PyMT cells after 3-day treatment with 1μM Zil or control DMSO in adherent culture (n = 3 per group). m, Sphere formation of MMTV-PyMT cancer cells in the presence of 1μM Zil after 7 days (technical replicate n = 8 per group of biological duplicates). Statistical analysis by two-sided t-test (b–d, f–m) and one sided t-test (e). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C. Reis e Sousa, E. Sahai, P. Scaffidi and J. Huelsken for scientific discussions, critical reading of the manuscript and sharing cell lines and mouse strains. We also thank members of the tumour-stroma interactions in cancer development (TSI) laboratory of The Crick Institute for scientific discussions, critical reading of the manuscript and practical support. We thank L. Jones for help in analysing the human breast cancer samples. We are grateful to R. Moore, E. Nye, B. Spencer-Dene and J. Bee for technical support with mice and mouse tissue. We also thank the Flow Cytometry Unit, the Bioinformatics & Biostatistics Unit and the In Vivo Imaging Facility for technical assistance. We are grateful to Cancer Research UK for the funding that has allowed this work.

Footnotes

AUTHOR INFORMATION

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nature medicine. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bald T, et al. Ultraviolet-radiation-induced inflammation promotes angiotropism and metastasis in melanoma. Nature. 2014;507:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galdiero MR, et al. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1402–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finisguerra V, et al. MET is required for the recruitment of anti-tumoural neutrophils. Nature. 2015;522:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature14407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nature cell biology. 2006;8:1369–1375. doi: 10.1038/ncb1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erler JT, et al. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan RN, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malanchi I, et al. Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature. 2012;481:85–89. doi: 10.1038/nature10694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calon A, et al. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-beta-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer cell. 2012;22:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oskarsson T, Batlle E, Massague J. Metastatic stem cells: sources, niches, and vital pathways. Cell stem cell. 2014;14:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffelt SB, et al. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345–348. doi: 10.1038/nature14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luu NT, Rainger GE, Buckley CD, Nash GB. CD31 regulates direction and rate of neutrophil migration over and under endothelial cells. Journal of vascular research. 2003;40:467–479. doi: 10.1159/000074296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condamine T, Ramachandran I, Youn JI, Gabrilovich DI. Regulation of tumor metastasis by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Annual review of medicine. 2015;66:97–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051013-052304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian BZ, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu M, et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013;339:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1228522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korkaya H, Liu S, Wicha MS. Breast cancer stem cells, cytokine networks, and the tumor microenvironment. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:3804–3809. doi: 10.1172/JCI57099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuyada A, et al. CCL2 mediates cross-talk between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts that regulates breast cancer stem cells. Cancer research. 2012;72:2768–2779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan HH, et al. Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells tip the balance of immune protection to tumor promotion in the premetastatic lung. Cancer research. 2010;70:6139–6149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snoussi K, Strosberg AD, Bouaouina N, Ben Ahmed S, Chouchane L. Genetic variation in pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1beta, interleukin-1alpha and interleukin-6) associated with the aggressive forms, survival, and relapse prediction of breast carcinoma. European cytokine network. 2005;16:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2010;10:181–193. doi: 10.1038/nrc2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho NK, Joo YC, Wei JD, Park JI, Kim JH. BLT2 is a pro-tumorigenic mediator during cancer progression and a therapeutic target for anti-cancer drug development. American journal of cancer research. 2013;3:347–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanaoka Y, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and their receptors: cellular distribution and function in immune and inflammatory responses. Journal of immunology. 2004;173:1503–1510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiraga T, Ito S, Nakamura H. Side population in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells exhibits cancer stem cell-like properties without higher bone-metastatic potential. Oncology reports. 2011;25:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheridan C, et al. CD44+/CD24- breast cancer cells exhibit enhanced invasive properties: an early step necessary for metastasis. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2006;8:R59. doi: 10.1186/bcr1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo PK, et al. CD49f and CD61 identify Her2/neu-induced mammary tumor-initiating cells that are potentially derived from luminal progenitors and maintained by the integrin-TGFbeta signaling. Oncogene. 2012;31:2614–2626. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park MK, et al. Novel involvement of leukotriene B(4) receptor 2 through ERK activation by PP2A down-regulation in leukotriene B(4)-induced keratin phosphorylation and reorganization of pancreatic cancer cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1823:2120–2129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenzel SE, Kamada AK. Zileuton: the first 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor for the treatment of asthma. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 1996;30:858–864. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donskov F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials. Seminars in cancer biology. 2013;23:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Y, et al. Prognostic value of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in early-stage breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;131:483–490. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Molecular and cellular biology. 1992;12:954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS letters. 1997;407:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieschke GJ, et al. Mice lacking granulocyte colony-stimulating factor have chronic neutropenia, granulocyte and macrophage progenitor cell deficiency, and impaired neutrophil mobilization. Blood. 1994;84:1737–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mombaerts P, et al. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao YA, et al. Shifting foci of hematopoiesis during reconstitution from single stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:221–226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanova A, et al. In vivo genetic ablation by Cre-mediated expression of diphtheria toxin fragment A. Genesis. 2005;43:129–135. doi: 10.1002/gene.20162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tkalcevic J, et al. Impaired immunity and enhanced resistance to endotoxin in the absence of neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Immunity. 2000;12:201–210. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen XS, Sheller JR, Johnson EN, Funk CD. Role of leukotrienes revealed by targeted disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase gene. Nature. 1994;372:179–182. doi: 10.1038/372179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao Y, Cao X. Revisiting the protective and pathogenic roles of neutrophils: Ly-6G is key! European journal of immunology. 2011;41:2535–2538. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.