Abstract

Background:

One of the reported obstacles to the achievement of universal access to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) prevention, treatment, care, and support programs includes stigma and discrimination from health workers, particularly nurses. Since nursing students would become future practising nurses and are most likely exposed to caring for people living with HIV/AIDS (PL WHA) during their training, it is of great importance to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of student nurses toward the reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive survey research design was used. A total of 150 nursing students were selected using the simple random sampling technique of fish bowl method with replacement. Data were obtained using a self-administered (33-item) validated questionnaire to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of student nurses with regard to HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination reduction strategies. Reliability of the tool was tested using Cronbach alpha (R) yielding a reliability value of 0.72. Data collected were analyzed with descriptive statistics of frequencies and percentages.

Results:

Majority (76.0%) of the respondents were females and 82.7% were married. Respondents were found to have high knowledge (94.0%) of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Also, 64% had moderate discriminatory attitude, 74% engaged in low discriminatory practice, while 26% engaged in high discriminatory practice.

Conclusions:

Student nurses had adequate knowledge about strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination; negative discriminatory attitude toward PLWHA and some form of discriminatory practices exist in participants’ training schools. It is, therefore, recommended that an educational package on reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination be developed and implemented for the participants.

Keywords: Attitude, discrimination, HIV, HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination, knowledge, Nigeria, nursing, practice, stigma, students

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 35 million people live with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) globally with more than two-thirds (70%) of these people residing in sub-Saharan Africa.[1] As the most populous country in Africa, Nigeria accounts for about 10% of the world's total AIDS population and has 3.2 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).[1]

Stigma is a common human reaction to disease and is described as a social process that involves identifying and using “differences” between groups of people to create and legitimize social hierarchies and inequalities.[2] Throughout history, many diseases have carried considerable stigma, including leprosy, tuberculosis, cancer, mental illness, and many sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS. Some of the characteristics shared by HIV/AIDS with other diseases that are highly stigmatized include its perception to be untreatable, degenerative, and fatal, its contagiousness and transmissibility, and the repellent, ugly, and upsetting appearance of the infected individual at the advanced stages of the disease.[3] Many international agencies including the World Health Organiz ation (WHO), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health have made combating HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination a top priority, as this phenomenon undermines public health efforts to combat the pandemic.[4,5,6,7,8] The phenomenon also negatively affects preventive behaviors such as condom use, HIV/AIDS test-seeking behavior, care-seeking behavior upon diagnosis, quality of care given to HIV/AIDS-positive patients, and perceptions and treatment of PLWHA by partners, families, and communities.[4]

One of the major settings in which stigmatization needs to be urgently addressed is the health care setting. In Nigeria, many people have been maltreated by health care providers or denied access to care because of the health care providers’ negative attitude to PLWHA. PLWHA have also been found to be subject of discrimination and stigmatization in the workplace by families and communities in the country.[9] This discriminatory behavior interferes with effective prevention and treatment by discouraging individuals from being tested or seeking information on how to protect themselves and others from HIV/AIDS.

Various studies have identified compromising and discriminatory attitudes of nurses toward patients with HIV/AIDS.[10,11,12,13] Nurses are the largest health care providers in the health sector and have a significant role to play in the prevention, care, support, and reduction of stigma and discrimination of PLWHA. It is, therefore, of great importance to assess the gaps in nursing students’ knowledge, attitude, and practice of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in order to improve their nursing training, since they will have an important role to play in halting this epidemic in the coming years.

The strategies for reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination require special skills and attitudinal changes. The strategies include acquiring in-depth knowledge about all aspects of HIV/AIDS, application of universal safety precautions, and care, support, and treatment for specific clinical problems. Therefore, health care personnel caring for HIV/AIDS patients need to acquire new knowledge, skills, and positive attitudes in practice as they become immersed in the multidisciplinary problems of HIV/AIDS care and reduction of stigma and discrimination. The knowledge and attitude of student nurses in relation to HIV is an important determinant of their willingness to care and the quality of the care they would render to HIV patients. Student nurses are the ones who would bear the mantle of nursing care in the nearest future. Their knowledge and attitude toward PLWHA during the course of their training can have a significant influence on them when they become registered nurses and possibly get involved in the care of HIV patients. Most notably, it is important to remember that student nurses are not excluded from harboring and delivering the devastating acts of stigma and discrimination. Insufficient knowledge might cause negative attitude and poor practice of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.

Few studies assessing the involvement of nursing students with regard to reduction of HIV/AIDS related-stigma and discrimination have been documented. Stavropoulou et al. explored nursing students’ perception about caring and communicating with HIV people in Greece and found discriminatory attitude to be prevalent among them.[14] In India, a study conducted to reduce HIV stigma among nursing students reported 87% and 95% demonstrating intent to discriminate while dispensing medications and drawing blood, respectively.[15] Furthermore, discriminatory attitude was found to be common among student nurses in Russia.[16] A lack of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination reduction studies in the literature among student nurses in Nigeria has resulted in a knowledge gap. This study, therefore, focuses on knowledge, attitude, and practice of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination reduction among student nurses in southwest Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used descriptive survey research design. The population for this study consisted of student nurses in their second and third year of nursing program from three schools of nursing in southwestern region of Nigeria. The second and third year nursing students were chosen because they had almost completed the nursing program and would thus provide a good indication of the knowledge, attitude, and practice of student nurses toward the reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. A total of 150 nursing students were selected from the three schools of nursing. The simple random sampling technique of fish bowl method with replacement was used to select 25 participants each from the second and third year of each school of nursing. Thus, 50 participants were selected from each school.

The instrument for data collection was a self-developed structured questionnaire that consisted of 33 items assessing socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitude, and practice of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. The questionnaire was pretested on 20 nursing students of another school of nursing in a different state in the southwestern region of Nigeria. The data collected was used to estimate the reliability of the instrument using Cronbach alpha (R) in order to bring out the internal consistency and construct validity of the instrument. The global Cronbach alpha value was found to be 0.72. The Cronbach alpha values for knowledge, attitude, and practice subscales were 0.703, 0.819, and 0.733, respectively. After the selection of respondents using simple random technique, the selected students were given the questionnaire and the same collected on the spot.

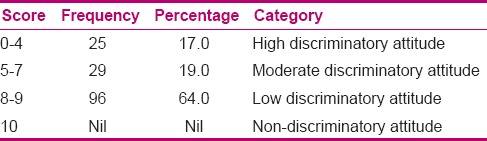

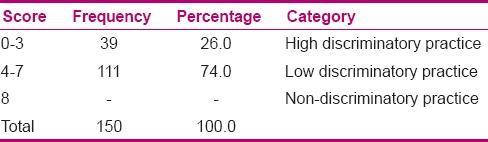

For the knowledge of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination, the correct responses were scored as 1 while the incorrect responses were scored as 0. The maximum obtainable knowledge score was 9; scores 0–4 was classified as low knowledge, 5–7 as moderate knowledge, while the scores 8–9 were classified as high knowledge. For attitudinal outcome, the correct responses were scored as 1 while the incorrect responses were scored as 0. The maximum obtainable attitudinal score was 10; scores 0–4 were classified as high discriminatory attitude, 5–7 as moderate discriminatory attitude, 8–9 as low discriminatory attitude, and 10 as non-discriminatory attitude. To calculate the practice score, the correct responses were scored as 1 while the incorrect responses were scored as 0. The maximum obtainable participation score was 8. A participation score of 0–3 was classified as high discriminatory practice, 4–7 as low discriminatory practice, and 8 as non-discriminatory practice. Tables, frequencies, and percentages were used to present data. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ethical committee of the nursing schools. After giving full explanation of the purpose of the study to the nursing students, their consent was taken and confidentiality was ensured. This allowed the researchers to have access to the school register of the second and third year nursing students.

RESULTS

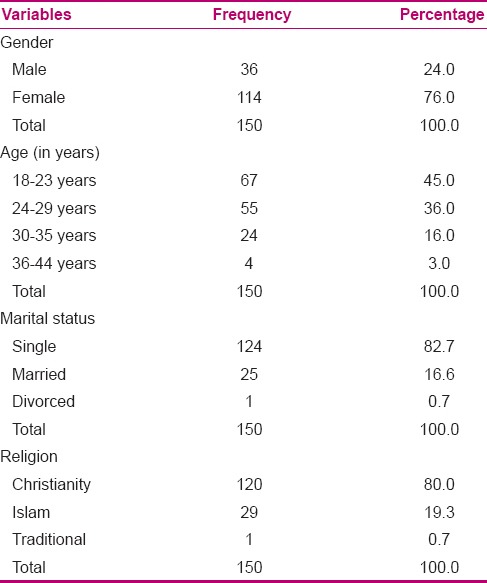

The socio-demographic characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1. Of the 150 respondents interviewed, 114 (76.0%) were females and 36 (24.0%) were males. Sixty-seven (45.0%) of the respondents were within 18–23 years age group. Majority 124 (82.7%) were single and 120 (80.0%) were Christians.

Table 1.

Frequencies and percentages of the demographic data of the participants

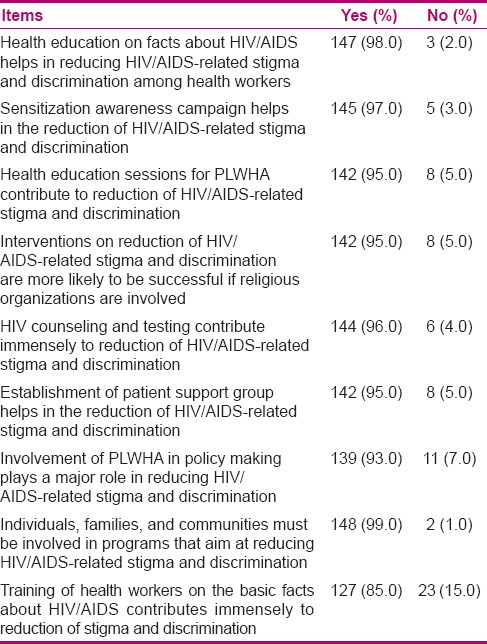

Table 2 shows the responses of participants on the knowledge of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. One hundred and forty-seven participants (98%) agreed that health education on facts about HIV/AIDS helps in reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination among health workers, and 145 participants (97%) agreed that sensitization awareness campaigns help to reduce HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Furthermore, 148 participants (99%) agreed that individuals, families, and communities must be involved in programs that aim at reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Overall, the knowledge of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination revealed that 94% of respondents had high knowledge [Table 3].

Table 2.

Participants’ knowledge about strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination (N=150)

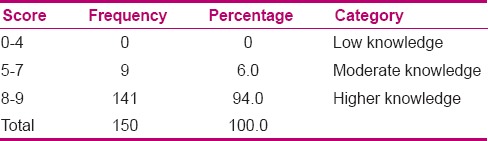

Table 3.

Frequency and percentage distribution of participants’ scores on knowledge about strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination

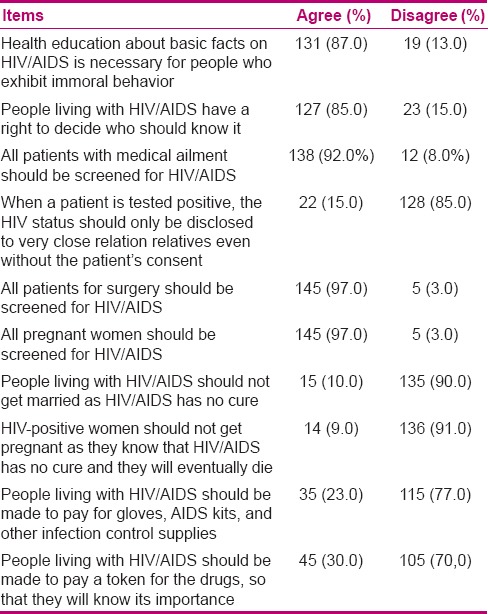

Table 4 shows the attitudes of participants toward PLWHA. One hundred and forty-five (97%) participants agreed that all pregnant women and all patients for surgery should be screened for HIV/AIDS. Majority of the participants (92%) also agreed that all patients with medical ailment should be screened for HIV/AIDS. One hundred and twenty-seven (85%) participants agreed that PLWHA have a right to decide who should know their status, and 91% agreed that HIV-positive women should not be pregnant as they know that HIV/AIDS has no cure and they will eventually die. Overall, the attitude toward strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination revealed that 64% of respondents had low discriminatory attitude and 19% had moderate discriminatory attitude [Table 5].

Table 4.

Attitudes of participants toward strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination (N=150)

Table 5.

Frequency and percentage distribution of participants’ scores on strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in PLWHA

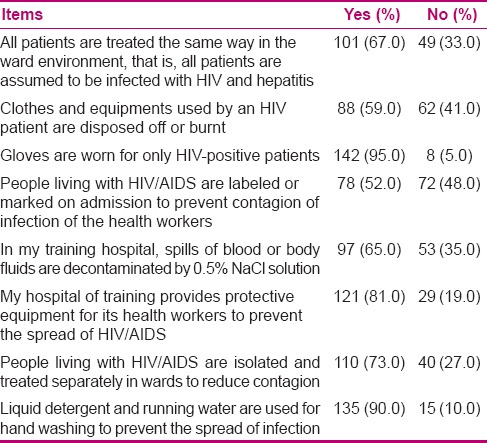

Table 6 shows the strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination as practised by the participants. Majority (95%) of the participants wore gloves alone for HIV-positive patients. One hundred and twenty-one (81%) participants agreed that their hospital of training provided protective equipment for its health workers to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS, and 90% agreed that liquid detergent and running water should be used for hand washing to prevent the spread of infection. Overall, the practice of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination revealed that 74% of respondents had low discriminatory practice while 26% had high discriminatory practice [Table 7].

Table 6.

Practice of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination (N=150)

Table 7.

Frequency and percentage distribution of participants’ scores on the practice of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination

DISCUSSION

In caring for people with AIDS, nursing students have to cope with their fear of contagion and their feelings of having not learned enough about HIV/AIDS to safely create an impact in the lives of the patients. Knowledge of strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination was high among nursing students. For example, majority (98%) of the participants in the study reported that health education on facts about HIV/AIDS helps in reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination among health workers. This is similar to previous findings in the literature which identified poor knowledge in regards to HIV/AIDS as a predictor of stigmatizing views about PLWHA.[17,18,19,20] Furthermore, previous findings among final year medical students also reported that greater knowledge about HIV/AIDS led to more positive attitudes toward HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.[21,22] This is why it is important to focus on improving educational platform in order to provide sufficient HIV education for nursing students during their training.

It has been noted that poor knowledge of HIV/AIDS is a predictor of stigmatizing views toward PLWHA. Therefore, several literature reports have emphasized that HIV training helps reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination.[22] For example, a study conducted among student nurses revealed that a specialized training course led to increased knowledge of HIV, which, in turn, led to positive attitudes toward PLWHA.[19] Educational programs have been reported to be highly effective in reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. These programs should provide accurate knowledge of the modes of transmission and the ways in which HIV is not transmitted, skills to interact with HIV-positive individ uals, human right laws which protect the infected persons, and values and norms in the society which contribute to stigmatizing and discriminatory behavior.[23] Similarly, increased sympathy and willingness to care for PLWHA was reported after a successful training intervention among Chinese health care providers.[18] These previous findings support the findings of this study which revealed that 85% of participants reported that training of health workers on basic facts about HIV/AIDS reduces HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.

This study revealed the existence of stigmatization of patients with HIV/AIDS among student nurses in Nigeria. Despite the National Policy on HIV/AIDS testing which states that “HIV testing of patients before or during their stay in hospital solely for the benefits of health worker's safety shall be prohibited,” majority of the student nurses agreed that all patients with medical ailment should be screened for HIV/AIDS. This is similar to the findings of another study conducted among doctors and nurses in Belize.[5] Knowledge, gender, and marital status have been reported to be associated with the acceptance of HIV testing.[24] Furthermore, majority of the participants in the study agreed that all pregnant women and all patients for surgery should be screened for HIV/AIDS. This is similar to the findings of a previous survey in Nigeria which revealed that a greater proportion of the participants reported that regardless of consent, routine HIV testing of all women attending antenatal care clinics and patients scheduled for surgery took place at their facilities and that there are circumstances where it is appropriate to test a patient for HIV/AIDS without the patient's knowledge or permission.[25] Majority of participants in this study also disagreed that relatives of patients with HIV/AIDS should be notified of the patient's status even without the patient's consent. However, they supported that PLWHA have a right to decide who should know their status. This is in contrast to the findings of a previous study conducted in Nigeria which revealed that majority of health care professionals believed that relatives/sexual partners of patients with HIV/AIDS should be notified of the patient's status even without the patient's consent, and also staff and health care professionals in the institution should be notified.[25] Nigeria is a signatory to numerous international and regional human rights declarations. One of these declarations of human rights set out Nigeria's obligations to protect the rights of PLWHA, including the right to marry and found a family, the right to non-discrimination, and the right to privacy. This is supported by findings of this study showing that 90% and 91% of participants disagreed that PLWHA should not get married or get pregnant, respectively.

On the other hand, some of the participants revealed non-discriminatory attitude to PLWHA by agreeing that PLWHA should not be made to pay for their drugs, gloves, AIDS kit, and other infection control supplies. However, it should be noted that in order for health care professionals to carry out their jobs effectively, they should be provided with adequate supplies of essential protective materials and basic medications. Therefore, when health care professionals are provided with adequate equipments, stigma and discrimination of PLWHA reduces.

With regards to acts of stigma and discrimination, more than half (52%) of the respondents agreed that charts/beds of patients with HIV/AIDS should be marked, so that clinic/hospital workers will know the patient's status. This is similar to the findings of this study showing that 73% of the participants agreed that HIV patients should be managed a separate ward and 78% agreed that PLWHA should be labelled on admission to prevent contagion of infection by health workers. Unusual attitudes such as “isolation of HIV patients in quarantine”, “discomfort for use of gloves” and assuming that “reporting of accidental exposure is not important” were reported by Hentgen et al.[26] Le Pont et al.,[27] and Shriyan et al.,[28] in their studies among healthcare workers, respectively. HIV/AIDS policy should also be extended abroad to enhance international collaboration in dealing with all aspects related to the disease [29]

Almost all (92%) the nursing students wanted HIV testing for every patient with medical ailments. Execution of discriminatory measures of safety precautions based on the serostatus of the individual could be the rationale for such opinion which is in line with the findings of Shivalli (2014)[30] who observed that majority of the nursing students wanted all inpatients to be tested for HIV. Lack of protective and other materials needed to treat and prevent the spread of HIV and related conditions have been reported to contribute to discriminatory behaviour. Therefore, the presence of these materials will reduce discriminatory acts. Although nursing students’ knowledge was satisfactory, there is a need of capacity building of nursing students to change their attitudes and reinforce universal precaution practices in work settings.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that it surveyed only a small group of all nursing students in Nigeria. However, the demographic characteristics of the participants are similar to those of other nursing students in other state. Unfortunately, the actual sample size of the study group was less than the sample size calculated before the start of this study. Additional studies of nursing students would be helpful to determine whether the results are generalizable.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

HIV/AIDS related stigma has been identified as a major barrier to HIV prevention efforts and an impediment to mitigating its impact on individuals and communities. Findings of this study revealed that majority of the participants’ have knowledge about strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination but there was existence of discriminatory attitude towards PLWHA and some form of discriminatory practices in participants’ training schools. Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that educational package on strategies for reducing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination for the student nurses be developed and implemented. Also, the Student nurses should be followed--up to ensure that what has been taught is put into practice. Registered nurses should be actively involved in mentoring student nurses by displaying positive attitude toward PLWHA and involving in AIDS stigma research and interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are very thankful to all the participants who willingly devoted their time for this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker R, Aggleton P, Attawell K, Pulerwitz J, Brown L. HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma and Discrimination: A Conceptual Framework and Agenda for Action: Horizons Programme. Washington, DC: Population Council; 2002. p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herek GM, Mitnick L, Buris S, Chesney M, Devine P, Fullilove MT, et al. Workshop report. AIDS and stigma: A conceptual framework and research agenda. AIDS Public Policy J. 1998;13:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. HIV and AIDS-Related Stigmatization, Discrimination and Denial: Forms, Contexts and Determinants. Research Studies from Uganda and India (Prepared for UNAIDS by Peter Aggleton) Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2000. pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrewin A, Chien LY. Stigmatization of patients with HIV/AIDS among doctors and nurses in Belize. AIDS Patients Care STDS. 2008;22:897–906. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation. Global Programme on AIDS: Report of a WHO Consultation in the Prevention of HIV and Hepatitis B Virus Transmission in the Health Care Setting. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1991. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Update: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and human immunodeficiency virus infection amonghealth-care workers. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:229–34. 239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FMOH/NMA. Handbook on HIV Infection and AIDS for Health Workers. Lagos: Gabumo Press; 1992. Federal Ministry of Health and Social Services Nigerian Association Guidelines; pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olowokere A. Ethical Issues on HIV/AIDS with Emphasis on Integrating the Care of People Affected by AIDS (PABA) into Reproductive Health Programme. Being a Paper Presented at the 2006 Conference of Heads of Schools of Nursing, Psychiatry and Midwifery at General Abdul Salami Youth Centre Minna, Niger State; Nigeria. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aisen AO, Shobowale MO. Health care workers’ knowledge on HIV/AIDS: Universal precautions and attitude towards PLWHA in Benin-City, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2005;8:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann U, Zulu J. How nurses in Cape Town clinics experience the HIV epidemic. AIDS Bulletin. 2005;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delobelle P, Rawlinson JL, Ntuli S, Malatsi I, Decock R, Depoorter AM. HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, practices and perceptions of rural nurses in South Africa. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:1061–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saob AE, Fawole AO, Sadoh WE, Oladimeji AO, Sotiloye OS. Attitude of health-care workers to HIV/AIDS. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006;10:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stavropoulou A, Stroubouki T, Lionaki A, Lionaki S, Bakogiorga H, Zidianakis Z. Student Nurses’ perception on caring for people living with HIV. Health Sci J. 2011;5:288–96. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah SM, Heylen E, Srinivasan K, Perumpi S, Ekstrand ML. Reducing HIV Stigma among nursing students: A brief intervention. West J Nurs Res. 2014;36:1323–37. doi: 10.1177/0193945914523685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suominen T, Laakkonen L, Lioznov D, Polukova M, Nikolaenko S, Lipiäinen L, et al. Russian nursing students’ knowledge level and attitudes in the context of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-a descriptive study. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12912-014-0053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao X, Sullivan SG, Xu J, Wu Z. China CIPRA Project 2 Team. Understanding HIV-related stigma and discrimination on a “blameless” population. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:518–28. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.6.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webber GC. Chinese health care providers’ attitudes about HIV: A review. AIDS care (Other) 2007;19:685–91. doi: 10.1080/09540120601084340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickles D, King L, Belan I. Attitudes of nursing students towards caring for people living with HIV/AIDS: Thematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:2262–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sengputa S, Banks B, Jonas D, Miles MS, Smith GC. HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS Stigma: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1075–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesić V, Kolarić B, Begovac J. Attitudes towards HIV/AIDS among final year medical students at the University of Zagreb Medical School-Better in 2002 than in 1993 but still unfavourable. Coll Antropol. 2006;30(Suppl 2):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platten M, Pham HN, Nguyen HV, Nguyen NT, Le GM. Knowledge of HIV and factors associated with attitudes towards HIV among final-year medical students at Hanoi Medical University in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HIVS/AIDS Stigma: Finding Solutions to Strengthen HIV/AIDS Programs. Washington DC: USA. International Center for Research on Women (ICRW); 2006. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 13]. International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) Available from: http://www.icrw.org/publications/hivaids-stigma-finding-solutions-strengthenhivaids-programs . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nwozichi CU, Farotimi AA. Knowledge and acceptance of HIV counselling and testing (HCT) among non-teaching staff of a private university in south-west Nigeria: The case of Babcock University. Asian J Nurs Educ Res. 2014;4:352–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reis C, Heisler M, Amowitz LL, Moreland RS, Mafeni JO, Anyamele C, et al. Discriminatory attitudes and practices by health workers towards patients with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hentgen V, Jaureguiberry S, Ramiliarisoa A, Andrianantoandro V, Belec M. Knowledge, attitude and practices of health personnel with regard to HIV-AIDS in Tamatave (Madagascar) Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2002;95:103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Pont F, Hatungimana V, Guiguet M, Ndayiragije A, Ndoricimpa J, Niyongabo T, et al. Assessment of occupational exposure to human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus in a referral hospital in Burundi, Central Africa. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:717–8. doi: 10.1086/502908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shriyan A, Roche R, Annamma Incidence of occupational exposures in a tertiary health care center. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2012;33:91–7. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.102111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nwozichi CU. Extending HIV/AIDS policy abroad through international collaboration aimed at promoting positive sexual behaviours of African students schooling in foreign countries”. Afr J AIDS Res. 2015;14:iii. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2015.1016990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shivalli S. Occupational exposure to HIV: Perceptions and preventive practices of Indian nursing students. Adv Prev Med. 2014;2014:296148. doi: 10.1155/2014/296148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]