Abstract

Ischiospinal dysostosis (ISD) is a polytopic dysostosis characterized by ischial hypoplasia, multiple segmental anomalies of the cervicothoracic spine, hypoplasia of the lumbrosacral spine and occasionally associated with nephroblastomatosis. ISD is similar to, but milder than the lethal/semilethal condition termed diaphanospondylodysostosis (DSD), which is associated with homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations of bone morphogenetic protein-binding endothelial regulator protein (BMPER) gene. Here we report for the first time biallelic BMPER mutations in two patients with ISD, neither of whom had renal abnormalities. Our data supports and further extends the phenotypic variability of BMPER-related skeletal disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13023-015-0380-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ischiospinal dysostosis, Diaphanospondylodysostosis, BMPER, Vertebral anomaly, Ischial hypoplasia

Ischiospinal dysostosis (ISD) is a polytopic dysostosis characterized by minor facial dysmorphism, ischial hypoplasia and short stature with a short spine caused by vertebral anomalies including hypoplasia of the lumbosacral spine, scoliosis and segmental defects of the cervicothoracic spine [1]. Eight patients have been reported so far [2–4] (Additional file 1: Table S1). Some of them showed mono- or polycystic kidneys with or without nephroblastomatosis [3, 4], neurogenic bladder and neurological deficits of the lower extremities [2]. Parental consanguinity in one patient suggested autosomal recessive inheritance, but the causative gene has been hitherto unknown [2]. Diaphanospondylodysostosis (DSD) is a lethal/semilethal skeletal dysplasia, the phenotype of which is similar to, but more severe than, that of ISD [5–12] (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2). Funari et al. identified mutations in the BMPER in four patients with DSD [13], and since then two additional DSD patients and three siblings with so-called attenuated form of DSD with BMPER mutations have been published [9, 12] (Table 1, Fig. 1). We report two ISD patients with biallelic mutations (three novel variants) in the BMPER gene, extending the spectrum of BMPER-related skeletal disorders.

Table 1.

List of mutations of BMPER reported previously and in the current study

| Numbera | cDNA | Protein | Frequency in ExAC | In-silico analysisb | Zygosity in proband | Diagnosis | Reference and comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.925C>T | p.Gln309* | NR | NS | Homozygous | DSD | [13] |

| 2 | c.26_35del10ins14 | p.Ala9Glufs*4 | NR | NS | Compound heterozygous | DSD | [8, 10, 11, 13]; same patient in four articles |

| 3 | c.1032+5G>A | NR | Splice | ||||

| 4 | c.514C>T | p.Gln172* | NR | NS | Heterozygousc | DSD | [13] |

| 5 | c.1109C>T | p.Pro370Leu | NR | Deleterious | Compound heterozygous | DSD | [13] |

| 6 | c.1638T>A | p.Cys546* | NR | NS | |||

| 7 | c.310C>T | p.Gln104* | NR | NS | Homozygous | DSD | [9]; two patients |

| 8 | c.251G>T | p.Cys84Phe | NR | Deleterious | Compound heterozygous | attenuated DSDd | [12] |

| 9 | c.1078+5G>A | NR | Splice | ||||

| 10 | c.416C>G | p.Thr139Arg | NR | Deleterious | Compound heterozygous | ISD | Current study |

| 11 | c.942G>A | p.Trp314* | NR | NS | |||

| 12 | c.1672C>T | p.Arg558* | 0.00004119e | NS | Homozygous | ISD | Current study |

| 13f | c.1988G>A | p.Cys663Tyr | 0.0000082 | Deleterious | Heterozygous | Current study |

NR not reported; NS nonsense mutation; DSD diaphanospondylodysostosis; ISD ischiospinal dysostosis

a Mutation number is also used in Fig. 1

b Prediction according to SIFT (http://sift-dna.org), AlignGVGD (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org) and PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2)

c Only one mutation identified in this patient

d It was described as attenuated DSD in the reference, but we consider them more likely to be ISD

e Not present in 2,040 normal alleles from a Korean population (in-house data)

f Variant of unknown clinical significance, found in patient with mutation No. 12

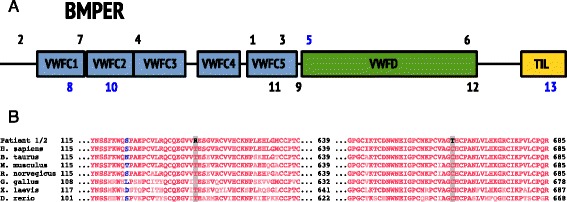

Fig. 1.

a: Locations of the mutations in the BMPER protein, previously reported (1–7) and identified in this study (8–11). Truncating mutations in black; missense in blue. b: Evolutionary comparison of the amino acids affected by novel missense mutations in this study. Blue and red colours indicate weakly and strongly conserved amino acids respectively

Patients

Patient 1 was a 2-year-old girl, a second child born to a healthy non-consanguineous Swedish couple after an uncomplicated pregnancy. The older brother was healthy. The patient was born in week 41+0 after an uncomplicated delivery with BW 2590 g (z = −1.9), BL 46 cm (z = −1.9), OFC 33 cm (z =−1.0). The neonatal period and psychomotor development were unremarkable. At age 14 months, she had short stature with short trunk, hypoplastic thorax, protruding abdomen, and mild facial dysmorphism. Extremities were normal. At age two years her height was 76.2 cm (z = −3.3), she had hearing loss, mechanism of which is still under investigation, delayed speech development, and wheezing upon cold exposure and physical exercise. Repeated renal ultrasonography did not show nephrogenic rests or cysts, but will continue until age 7 years.

Patient 2 was a 19-year-old male, a second child of a healthy non-consanguineous Korean couple. He was born after an uncomplicated full-term pregnancy with BW 3190 g (z = −0.43), BL 46 cm (z = −1.42), and OFC 35 cm (z = 0.20). Respiratory distress immediately after birth required oxygen therapy. Abdominal distension, hydronephrosis and urethral stricture were noted during the neonatal period, but neither nephrogenic rests nor cysts. He showed mild facial dysmorphic features, a short trunk and pectus carinatum. At age three months, he required brief mechanical ventilation due to pneumonia and suffered from seasonal asthma attacks thereafter. Lack of urination control required intermittent catheterization from two years of age. He suffered from fecal incontinence and impaction. He stood with assistance and spoke only single words at age two years. Progressive right pes equinus deformity developed along with deterioration of lower extremity motor function, which limited outdoor ambulation to about five minutes at age 19 years. Untethering of the spical cord was considered but the patient was not compliant. His height was 143 cm (z = −5.67) and weight 27.6 kg (z = −9.23), and his school performance is normal. The radiographic phenotypes are summarized in Figs. 2 and 3 and clinical characteristics in Additional file 1: Table S1.

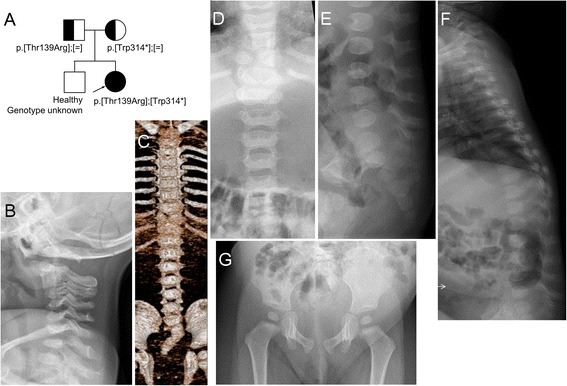

Fig. 2.

a: Pedigree and mutations in patient 1. b: Radiological examination at age 15 months shows narrowing of the intervertebral spaces of C2/3 and C3/4 presumably due to nonosseous synostosis. c-f: Radiological examinations at age 11 months. Butterfly vertebra is evident in T9. Only ten pairs of the ribs and 11th rib of the right are seen. The lumbar vertebral bodies are small, and ossification of the neural arches is defective. Caudal narrowing of the lumbar interpedicular distance is seen. The sacrum is hypoplastic and deviated rightward. g: Ossification of the ischial rami is defective, and the ischiopubic synchondroses are wide

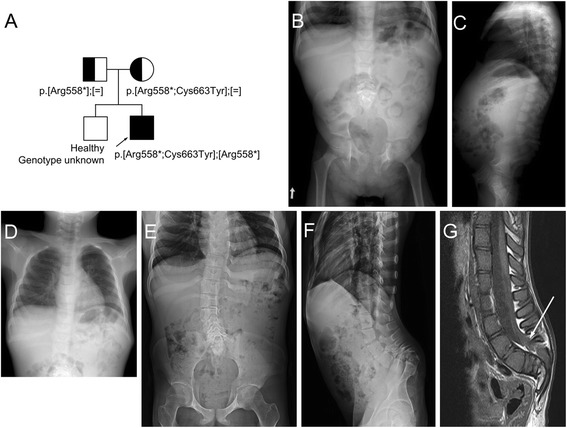

Fig. 3.

a: Pedigree and mutation in patient 2. b, c, d: Radiographs obtained at age 6 years show hypoplastic lumbar vertebral bodies, narrow interpedicular distance through the lumbar spine due to hypoplastic pedicles. Note absent coccygeal bones on the lateral spine, flared iliac wings, flat acetabulum and mild coxa valga. Short and tapering appearance of the bilateral ischial bones and wide ischiopubic junction is noted. Chest radiograph shows dysplastic and partly unossifed right upper ribs. e, f, g: Radiographs and MR imaging of the lumbosacral spine taken at age 19 years show mild thoracic and lumbar scoliosis with vertebral rotation, remarkable narrowing of the spinal canal with touching of the vertebral bodies to the posterior neural arch owing to absent/hypoplastic pedicles through lumbosacral vertebrae, and reveal lower lying spinal cord tethered to the lumbosacral junction (arrow). Pelvis AP radiograph shows hypoplastic ischium and inferior pubic rami, resulting in persistent gap between ischiopubic junction. Hip joint space is narrow

For patient 1, whole exome, subsequent Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis of the family revealed compound heterozygous mutations in the BMPER: NM_133468_4:c.[416C>G];[942G>A], p.[Thr139Arg];[Trp314*] (Fig. 3a). The amino acid substituted by the missense mutation is highly conserved among species (Fig. 3b). For patient 2, Sanger sequencing of the BMPER showed three sequence variants: NM_133468_4: c.[1672C>T;1988G>A];[c.1672C>T], p.[Arg588*;Cys662Tyr];[Arg588*]. The two variants on the same allele were inherited from the mother and the single mutation from the father (Fig. 3a). The variant NM_133468.4:c.1988G>A; p.Cys663Tyr is rare and predicted to be pathogenic (Table 1), but as the truncating mutation p.Arg558* is located upstream, p.Cys663Tyr substitution is most probably not involved in pathogenesis of this patient’s ISD.

Discussion

Previous reports ascertained biallelic BMPER mutations in six patients with DSD [9, 13] and three siblings with attenuated DSD [12]. In this report we show that ISD a disorder phenotypically similar, but much milder, than DSD is also caused by biallelic mutations in the BMPER gene.

The BMPER encodes a 658 amino acid protein, which regulates organogenesis through the BMP signaling pathway. It is highly expressed in lungs, brain and chondrocytes. The knockout mice for the Bmp-binding protein crossveinless 2 (Bmper) show defects of vertebral and cartilage development, renal hypoplasia, as well as abnormal lung alveoli [14]. The knockout mouse phenotype is recapitulated by the manifestations in patients with BMPER mutations. The most prominent features are vertebral segmentation anomalies and kidney abnormalities [2–4, 7–9, 11]. Kidney abnormalities (cysts and nephroblastomatosis) have been reported in most patients with DSD [7–11], but only in some patients with ISD [3, 4]. Patient 2 has hydronephrosis due to neurogenic bladder. However, neither renal cysts nor nephroblastomatosis were present in our patients. Our observation indicates that kidney abnormalities are not necessarily a feature in mildly affected patients with BMPER mutations.

Patient 1 is compound heterozygous for a missense variant p.Thr139Arg and for a nonsense mutation p.Trp314*, which could explain her milder phenotype. Patient 2 is homozygous for the nonsense mutation p.Arg558*, which is predicted to result in a stop codon in the von-Willebrand factor D domain and loss of Trypsin-inhibitor like domain (Fig. 1a). With the available data, it is impossible to predict which mutations cause DSD and which cause ISD. It may be that some nonsense mutations undergo nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, while others do not and that the latter may retain some residual function. Also, other genetic factors might modify the clinical phenotype. Further molecular studies are needed to elucidate the molecular impact of the different mutations in BMPER.

In conclusion, our report extends the phenotypic variabilities in BMPER-related skeletal disorders. This dysostosis family encompasses phenotypes from mild ISD to lethal DSD.

Consent statement

The cases are reported with informed parental and patients consents and with permission from the regional Ethical Boards of the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden and Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Acknowledgement

The families are acknowledged for participation. The authors thank Dr Emma Tham for English revision of this manuscript, Prof. Woong Yang Park for his in-house genomic data of normal Korean population, and Prof. Sung Soo Kim for the neonatal history of patient 2. Financial support was provided through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet; by grants from Kronprinsessan Lovisas and Axel Tiellmans Minnesfond, Samariten, Sällskapet Barnavård and Promobilia Foundations; and through Genome Technology to Business Translation Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning of the government of Republic of Korea (NRF-2014M3C9A2064684). The study sponsors had no role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Abbreviations

- ISD

Ischiospinal dysostosis

- DSD

Diaphanospondylodysostosis

- BMPER

Bone morphogenetic protein-binding endothelial regulator protein

- BW

Birth weight

- BL

Birth length

- OFC

Occipitofrontal circumference

- VWFC

Von Willebrand factor type C domain

- VWFD

Von Willebrand factor type D domain

- TIL

Trypsin inhibitor-like domain

Additional files

Summary of the patients with ISD and DSD, previously reported and in the current study. (DOCX 31 kb)

Fetuses reported in the literature suspected to have DSD (DOCX 23 kb)

Footnotes

Ekaterina Kuchinskaya and Giedre Grigelioniene contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EK, LH, TJC recruited the subjects, gathered patient history and clinical information. GG1 and AH performed the molecular analysis of patient 1, and TJC and HL of patient 2. OHK and GN analyzed radiological images. GG2 performed evolutionary comparison of the known BMPER variants, and prepared Fig. 1. GG1, EK, and TJC wrote the manuscript, which was read, corrected and approved by all coauthors.

Authors’ information

EK, GG1 are geneticists; AH a PhD candidate; LH a pediatrician; GG2 a bioinformatician/programmer; HL a lab technician; OHK and GN radiologists; and TJC a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon.

Contributor Information

Giedre Grigelioniene, Phone: +46(0)8-517 739 21, Email: Giedre.Grigelioniene@ki.se.

Tae-Joon Cho, Phone: +82-2-2072-2878, Email: tjcho@snu.ac.k.

References

- 1.Spranger JW, Brill PW, Nishimura G, Superti-Furga A, Unger S. Bone dysplasias; an atlas of genetic disorders of skeletal development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 732–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishimura G, Kimizuka M, Shiro R, Nii E, Nishiyama M, Kawano T, et al. Ischio-spinal dysostosis: a previously unrecognised combination of malformations. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29(3):212–7. doi: 10.1007/s002470050574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spranger J, Self S, Clarkson KB, Pai GS. Ischiospinal dysostosis with rib gaps and nephroblastomatosis. Clin Dysmorphol. 2001;10(1):19–23. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura G, Kim OH, Sato S, Hasegawa T. Ischiospinal dysostosis with cystic kidney disease: report of two cases. Clin Dysmorphol. 2003;12(2):101–4. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nisbet DL, Chitty LS, Rodeck CH, Scott RJ. A new syndrome comprising vertebral anomalies and multicystic kidneys. Clin Dysmorphol. 1999;8(3):173–8. doi: 10.1097/00019605-199907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prefumo F, Homfray T, Jeffrey I, Moore I, Thilaganathan B. A newly recognized autosomal recessive syndrome with abnormal vertebral ossification, rib abnormalities, and nephrogenic rests. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A(3):386–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales M, Verloes A, Saint Frison MH, Perrotez C, Bourdet O, Encha-Razavi F, et al. Diaphanospondylodysostosis (DSD): confirmation of a recessive disorder with abnormal vertebral ossification and nephroblastomatosis. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;136A(4):373–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatanavicharn N, Graham JM, Jr, Curry CJ, Pepkowitz S, Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, et al. Diaphanospondylodysostosis: six new cases and exclusion of the candidate genes, PAX1 and MEOX1. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(19):2292–302. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Neriah Z, Michaelson-Cohen R, Inbar-Feigenberg M, Nadjari M, Zeligson S, Shaag A, et al. A deleterious founder mutation in the BMPER gene causes diaphanospondylodysostosis (DSD) Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(11):2801–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scottoline B, Rosenthal S, Keisari R, Kirpekar R, Angell C, Wallerstein R. Long-term survival with diaphanospondylodysostosis (DSD): survival to 5 years and further phenotypic characteristics. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(6):1447–51. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tasian SK, Kim GE, Miniati DN, DuBois SG. Development of anaplastic Wilms tumor and subsequent relapse in a child with diaphanospondylodysostosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(7):548–51. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182465b58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zong Z, Tees S, Miyanji F, Fauth C, Reilly C, Lopez E, et al. BMPER variants associated with a novel, attenuated subtype of diaphanospondylodysostosis. J Hum Genet. 2015;60(12):743–7. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funari VA, Krakow D, Nevarez L, Chen Z, Funari TL, Vatanavicharn N, et al. BMPER mutation in diaphanospondylodysostosis identified by ancestral autozygosity mapping and targeted high-throughput sequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(4):532–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeya M, Kawada M, Kiyonari H, Sasai N, Nakao K, Furuta Y, et al. Essential pro-Bmp roles of crossveinless 2 in mouse organogenesis. Development. 2006;133(22):4463–73. doi: 10.1242/dev.02647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]