Abstract

Objectives

Head lice infestation is one of the most important health problems, generally involving children aged 5–13 years. This study aims to estimate the prevalence of head lice infestation and its associated factors among primary school children using systematic review and meta-analysis methods.

Methods

Different national and international databases were searched for selecting the relevant studies using appropriate keywords, Medical Subject Heading terms, and references. Relevant studies with acceptable quality for meta-analysis were selected having excluded duplicate and irrelevant articles, quality assessment, and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria. With calculating standard errors according to binomial distribution and also considering the Cochrane's Q test as well as I-squared index for heterogeneity, pediculosis prevalence rate was estimated using Stata SE V.11 software.

Results

Forty studies met the inclusion criteria of this review and entered into the meta-analysis including 200,306 individuals. Using a random effect model, the prevalence (95% confidence interval) of head lice infestation among primary school children was estimated as 1.6% (1.2–2.05), 8.8% (7.6–9.9), and 7.4% (6.6–8.2) for boys, girls, and all the students, respectively. The infestation rate was found to be associated with low educational level of parents, long hair, family size, mother's job (housewife), father's job (worker/unemployed), using a common comb, lack of bathrooms in the house, and a low frequency of bathing.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of head lice infestation among Iranian primary school children is relatively high with more prevalence among girls. We also found that economic, social, cultural, behavioral, and hygienic factors are associated with this infestation.

Keywords: head lice, infestation, pediculosis, primary students, prevalence

1. Introduction

Public health is a main factor of development in each community [1]. Despite the promotions in health and medical education, external parasitic infestation is a threat for community health development which is still considered as a public health concern [2]. Head lice are insects living as external parasites on humans and animals body. Human infestations occur as head lice (the most common type), body lice, and pubic lice [3].

Head lice infestation is a main public health problem and a great threat for personal hygiene involving children aged between 5 years and 13 years [4]. The disease is widespread around the world but is more common in developing countries, among school age children, and in crowded places with low socio-economic and poor hygiene conditions 5, 6, 7. Indicators concerning the infestation of head lice are used to assess the health, cultural, and economic situation of rural and urban communities [8].

Epidemic relapsing fever and epidemic typhus can be transmitted by lice. Because of frequent blood feeding and saliva injection, fatigue, psychological irritability, paranoia, and weakness can also occur. Other related complications are as follows: depression, hyperthermia, headache, feeling of heaviness in the body, muscle rigidity, attention deficit in the class and educational failure, insomnia, lack of social status, developing secondary infections, hair loss, and allergies 7, 8, 9.

Different prevalences of head lice among primary school children in the world have been reported. According to the results of a study [10], head lice prevalence was estimated as 4.8% (The Netherlands), 35% (Brazil), 1.2% (Turkey), 28.8% (Venezuela), and 29.7% (Argentina). Such variations have been observed in different provinces of Iran such as 4% in Urmia [10], 13.5% in Hamedan [8], 1.8% in Kerman [11], and 4.7% in Sanandaj [12].

The initial search results showed that different studies have been carried out to estimate the prevalence of head lice infestation among Iranian primary school children. There are remarkable variations in the results of these studies limiting their application for decision making and policy making. To provide reliable evidence, combining the findings of different studies using systematic review and meta-analytic methods is considered as an appropriate solution. This study aims to estimate the prevalence of pediculosis among Iranian primary school children using meta-analysis techniques.

2. Materials and methods

The current study is a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of head lice (Pediculosis capitis) among primary school children in Iran.

2.1. Search strategy

Different national (SID, Iranmedex, Magiran, and Irandoc) and international (PubMed, Google scholar, Scopus, and ScienceDirect) databases were investigated to provide articles published from January 1, 2000 until January 20, 2015. The search strategy was performed using keywords including: “epidemiology”, “prevalence”, “infestation”, “head louse”, “head lice”, “Pediculus humans capitis”, “pediculosis”, “primary school students”, “primary students”, “school children”, and “Iran”, as well as their Farsi equivalents.

Searching was conducted from January 21, 2015 to February 10, 2015. To increase the search sensitivity and to investigate more evidence, references of published articles were hand searched. Two researchers independently reviewed the studies for a possible inclusion in the review using an eligibility form. In addition, to find the results of unpublished studies, we interviewed some related experts and research centers.

2.2. Study selection

First the titles, then the abstract, and finally the full text of the articles were consulted to retrieve the studies fit for the review. The relevant studies were selected independently by two researchers. It should be noted that in order to prevent reprint bias, the findings of all studies were carefully reviewed and any duplicated research was excluded.

2.3. Quality assessment

Selected articles were assessed for quality using a standard checklist applied in previous studies [13]. Based on the components used in the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology checklist [14], a checklist was designed and used in the current systematic review including 12 questions about different methodological aspects of a study such as sample size estimation and selection, type of study, study population, data collection method and instrument, variable definition, diagnostic method of pediculosis infestation, statistical tests, objectives of the study, appropriate illustration, and presentation of findings according to the objectives. Studies obtaining at least eight quality scores [13] were entered in the final meta-analysis.

2.4. Inclusion criteria

All Persian and English written papers that passed the necessary assessment steps, received the required quality scores, and also estimated the infestation rate for all students or boys or girls, were entered in the meta-analysis.

2.5. Exclusion criteria

Studies without prevalence results for all students or according to both sex, those without definite sample size, abstracts presented in congresses without full text, and case–control studies and clinical trials that could not report a correct estimate of prevalence were excluded from the meta-analysis step.

2.6. Data extraction

All necessary information such as title, first author name, date of the study conduction, sample size (total, boys and girls), type of the study, sampling method, study area, language, prevalence of infestation according to gender, p value for the association between infestation and potential risk factors (educational levels and parents' profession, hair length, shared use of personal cosmetics, family size, easy access to bathroom or having bathroom in the house, and number of bathing occasions per week) were extracted from each study and entered into an excel spreadsheet. Meanwhile, two researchers independently extracted the data.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All collected data were entered into STATA version 11 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Standard error of the prevalence in each study was calculated according to binomial distribution. Cochrane test (Q) and I2 indices were applied to determine the heterogeneity of the study results. Due to the significant heterogeneity, a random effect model was used to estimate the total and gender specific prevalence's of pediculosis. In addition, to minimize the random variations between the point estimates, results of the studies were adjusted using Bayesian analysis methods. Finally, we assessed the potential effects of different variables on the mentioned heterogeneity using met regression methods. Having conducted a sensitivity analysis, studies influencing the heterogeneity were determined. The forest plot was designed to illustrate the point prevalence's of the selected studies as well as their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In this graph, the size of each box indicated the study weight, while the CI was illustrated by the lines crossing the boxes.

3. Results

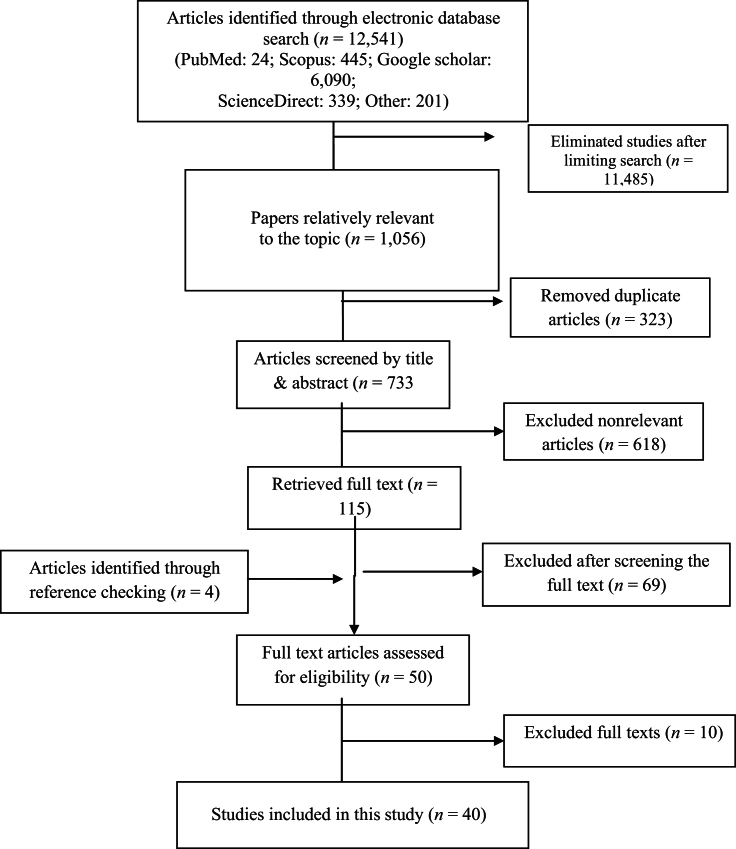

In the first phase of study search, 12,541 records were identified. Restricting the search strategy, the relatively relevant studies were reduced to 1,056. In the next steps, 323 duplicate papers and 618 irrelevant articles (during the title or abstract review) were excluded. During the quality assessment, 69 studies were removed, while four papers were added after review of references. Finally, 40 studies 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 were determined eligible to enter into the meta-analysis (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search and review flowchart for selection of primary studies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis of prevalence of head lice in primary school students in Iran.

| ID | First author | Publication y | Language of publication | Place of study | Sample size (N) |

Prevalence (%) |

Association between prevalence of head lice with variables of: (P-value) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Hair sizea | Sharing personal items | Education of mother | Education of father | Job of mother | Job of father | Family size | Bathing facilities in the house | Bathing frequency | |||||

| 1 | Hazrati Tappeh [4] | 2012 | EN | West Azarbaijan | 2,040 | 866 | 1,174 | 4 | 1.8 | 5.5 | <0.05 | — | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | NS |

| 2 | Kamiabi [7] | 2005 | EN | Kerman | 1,200 | 564 | 636 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 6.8 | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | — |

| 3 | Mohammadi-Azni [15] | 2014 | EN | Semnan | 2,700 | — | 2,700 | 3.6 | — | 3.6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | Moradi [16] | 2009 | EN | Hamadan | 900 | 450 | 450 | 1.3 | 0.44 | 2.2 | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | — | NS | — | — |

| 5 | Motevalli Haghi [17] | 2014 | EN | Golestan | 1,510 | — | 1,510 | 3.6 | — | 3.6 | — | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | — |

| 6 | Nazari [18] | 2007 | EN | Hamadan | 847 | 440 | 407 | 6.85 | 0.7 | 13.5 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | NS | <0.05 | — | — |

| 7 | Salehi [19] | 2014 | EN | Khoozestan | 624 | 302 | 322 | 4.3 | 0 | 8.4 | — | — | NS | NS | — | NS | — | — | — |

| 8 | Alempour-Salemi [20] | 2003 | EN | Sistan and Baluchestan | 918 | — | 918 | 27 | — | 27 | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | Sayyadi [21] | 2013 | EN | Kermanshah | 358 | — | 358 | 15.8 | — | 15.8 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | <0.05 | — | <0.05 |

| 10 | Shayeghi [22] | 2010 | EN | East Azerbaijan | 500 | 200 | 300 | 4.8 | 2 | 6.7 | — | — | NS | <0.05 | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | |

| 11 | Soleimani [23] | 2007 | EN | Hormozgan | 515 | 246 | 269 | 23.9 | 11.1 | 35.3 | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | — |

| 12 | Vahabi [12] | 2012 | EN | Kurdistan | 810 | — | 810 | 4.7 | — | 4.7 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | — | — | NS |

| 13 | Vahabi [24] | 2013 | EN | Kermanshah | 750 | — | 750 | 8 | — | 8 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | — | — | NS |

| 14 | Yousefi [25] | 2012 | EN | Kerman | 1,772 | 926 | 846 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.6 | NS | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | — | <0.05 | — | <0.05 |

| 15 | Motovali-Emami [11] | 2008 | EN | Kerman | 40,586 | 19,774 | 20,812 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.9 | — | — | <0.05 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 16 | Afshari [26] | 2013 | Persian | Tehran | 10,000 | — | 10,000 | 1.25 | — | 1.25 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | NS | NS |

| 17 | Arjomanzadeh [27] | 2001 | Persian | Booshehr | 3,913 | 1,962 | 1,951 | 12 | 2 | 22 | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | — |

| 18 | Bashiribod [28] | 2001 | Persian | Tehran | 1,921 | — | — | 15.8 | — | — | <0.05 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 19 | Davari [29] | 2005 | Persian | Kurdistan | 1,195 | — | — | 19.7 | — | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| 20 | Doroodgar [30] | 2010 | Persian | Esfahan | 3,589 | 2,096 | 1,493 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.1 | — | — | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | — |

| 21 | Farzinnia [31] | 2004 | Persian | Qom | 1,650 | — | 1,650 | 4.5 | — | 4.5 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | <0.05 | NS | — |

| 22 | Ghaderi [32] | 2010 | Persian | South Khorasan | 1,226 | — | — | 4.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 23 | Gholami parizad [33] | 2001 | Persian | Ilam | 658 | 315 | 343 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | — |

| 24 | Hosseini [34] | 2014 | Persian | North Khorasan | 250 | 120 | 130 | 10 | 4.2 | 15.4 | NS | NS | — | — | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 25 | Javidi [35] | 2004 | Persian | Razavi Khorasan | 769 | — | 769 | 7.6 | — | 7.6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 26 | Modarresi [36] | 2013 | Persian | Mazandaran | 1,846 | 889 | 957 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 8.8 | — | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | — | NS | — | — |

| 27 | Moradi [37] | 2012 | Persian | Hamadan | 8,568 | — | — | 8.2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 28 | Motalebi [38] | 2000 | Persian | Gonabad | 846 | — | — | 10.3 | — | — | — | <0.05 | — | — | — | — | — | — | <0.05 |

| 29 | Motevalli-Emami [39] | 2003 | Persian | Esfahan | 26,421 | — | — | 0.8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 30 | Motevalli-Haghi [40] | 2014 | Persian | Mazandaran | 45,237 | 9,213 | 36,024 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.9 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | — |

| 31 | Noroozi [41] | 2013 | Persian | Gom | 900 | — | 900 | 13.3 | — | 13.3 | — | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| 32 | Poorbaba [42] | 2004 | Persian | Guilan | 2,893 | 1,493 | 1,400 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 5.7 | — | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | — | — | — |

| 33 | Rafie [43] | 2009 | Persian | Khoozestan | 810 | — | 810 | 11 | — | 11 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| 34 | Rafinejad [44] | 2006 | Persian | Guilan | 4,244 | 2,115 | 2,129 | 9.2 | 4.7 | 13.7 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| 35 | Saghafipour [45] | 2012 | Persian | Gom | 1,725 | — | 1,725 | 7.6 | — | 7.6 | — | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| 36 | Shahraki [46] | 2001 | Persian | Kohgiluyeh and Boyer–Ahmad | 12,247 | 6,438 | 5,809 | 11 | 1.3 | 21.8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 37 | Soleimanizadeh [47] | 2002 | Persian | Bandarabbas | 3,249 | — | — | 12.3 | — | — | <0.05 | — | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | — |

| 38 | Yaghmaie [48] | 2007 | Persian | Kurdistan | 600 | — | 600 | 7.7 | — | 7.7 | NS | — | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — |

| 39 | Zabihi [49] | 2005 | Persian | Mazandaran | 2,300 | 1,150 | 1,150 | 2.2 | 0.96 | 3.5 | — | — | NS | <0.05 | NS | NS | <0.05 | — | — |

| 40 | Zahirnia [8] | 2005 | Persian | Hamadan | 7,219 | — | 7,219 | 13.5 | — | 13.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

EN = English; NS = not significant.

Short, Moderate, High.

Selected studies for meta-analysis included a total of 200,306 primary school students, 49,559 boys and 107,321 girls. Type of studies were determined for 31 studies (16 descriptive and 15 descriptive-analytic). Among the 32 studies reporting the sampling method, 19 of which had randomization, five had consensus, and eight had multistage cluster sampling. Publication dates varied between 2000 and 2014.

The total prevalence of infestation varied from 0.47% in the Doroodgar et al [30] study with a sample size of 3,589 conducted in Isfahan (center of Iran) in 2013 to 27% in the study carried out by Alempour-Salemi et al [20]among 918 students in Sistan-Baloochistan province (south-east of Iran). As illustrated in Table 1, infestation prevalences among boys differed from zero in the Salehi et al [19] study to 11.1% in the Soleimani et al [23] study. The corresponding figures for girls were 0.1% (Doroodgar study [30]) and 35.3% (Soleimani study [23]) respectively. Using Bayesian analysis method and adjustment of the effect of studies, the total prevalence modified to 0.5% (95% CI: 0.3–0.7) in the Doroodgar study [30] and 23.1% (95% CI: 20.5–25.6) in the Alempour-Salemi study.

According to the results of the sensitivity analysis, the Motevalli-Haghi et al [40] study and the Motevalli-Emami et al [39] study carried out among 45,237 and 26,421 students respectively affected the amount of heterogeneity more than other studies. However, excluding these studies from the meta-analysis did not remove the heterogeneity (p < 0.0001). Because the heterogeneity did not change after exclusion of six articles, meta-analysis was carried out for all 40 studies using a random effect model to prevent more reduction of the primary studies.

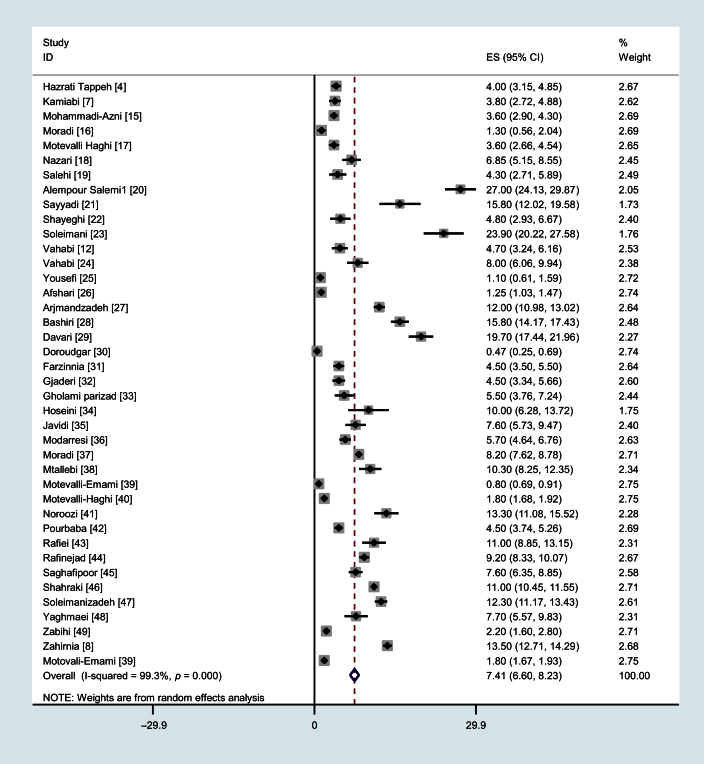

The forest plot (Figure 2) shows the total prevalence of head lice per study and a pooled estimate. Using a random effect model, the total prevalence of head lice among Iranian primary school children was estimated as 7.4% (95% CI: 6.6–8.2). The corresponding estimates for boys and girls were 1.6% (95% CI: 1.2–2.05) and 8.8% (95% CI: 7.6–9.9), respectively (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of head lice in primary school students by included studies in the current meta-analysis and overall estimate. CI = confidence interval; ES = estimate; ID = identification.

Table 2.

Pooled estimated of head lice prevalence in primary school students in Iran, according to the result of the meta-analysis.

| Prevalence by | Sample size | Pooled estimate (%), 95% CI | Heterogeneity test |

Heterogeneity (I2 %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square(Q) | p | ||||

| Boys | 49,559 | 1.6 (1.2–2.05) | 244.9 | <0.001 | 92.6 |

| Girls | 107,321 | 8.8 (7.6–9.9) | 4,636.5 | <0.001 | 99.3 |

| Total | 200,306 | 7.4 (6.6–8.2) | 5,633.7 | <0.001 | 99.3 |

CI = confidence limit.

The effects of publication date and the climate of the study area on the pooled estimate of prevalence were investigated using met regression models. It was noted that only the effect of publication date was statistically significant, i.e., there were four unit decreases per year in the prevalence of pediculosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Related factors with heterogeneity of head lice prevalence in the current meta-analysis.

| Variables | Univariate meta regression |

Multivariate meta regression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | |

| Publication yr | −0.4 | 0.041 | −0.4 | 0.046 |

| The climate of the study area | −0.5 | 0.647 | −0.3 | 0.719 |

The association between hair length and pediculosis was investigated in 14 studies, eight of which reported a significant effect of long hair. Of 15 studies assessing the relationship between pediculosis and shared use of personal hygiene items, eight studies observed significant associations between use of a common comb and developing head lice infestation.

Twenty-seven studies investigated the influence of the level of mother's education, all of which showed that the risk of infestation was significantly higher among children whose mothers had low levels of education. In the case of education of fathers, 21 out of 27 studies reported significant positive associations between low levels of father's education and pediculosis.

The associations between the jobs of mothers and fathers were investigated in 19 studies and 23 studies, respectively. Students whose mothers were housewives (5 studies) as well as those whose fathers were worker or jobless (14 studies) were significantly at higher risk of pediculosis.

Twenty-two studies assessed the relationship between prevalence and family size, 17 of which reported a higher risk of infestation in students living in bigger size families. The effect of having a bathroom in the house on pediculosis was significant in nine out of 14 studies investigating these associations. Of these, seven papers showed higher frequencies of infestation among children without access to a bathroom within their homes and also eight out of 14 studies reported higher rates of infestation among students with a lower frequency of bathing per week.

4. Discussion

The main outcome of this meta-analytic study carried out among 200,306 Iranian elementary school children was that the overall head lice infestation rate was 8.8% with girls infested 5.5 fold higher than boys. We also observed that the infestation was more common among students with low educated parents, long hair, big family size, housewife mothers, worker or jobless fathers, using shared combs, lack of bathrooms, or lower frequency of bathing at home.

According to Table 4, 14 studies showed the prevalence of infestation from 4.1% in the Oh et al [59] study in Korea to 40.3% in the Gazmuri et al [50] study in Chile. Infestation rates in Chile [50], Egypt [51], Turkey 1, 52, 53, 55, Thailand [56], Jordan [57], Argentina [60], Malaysia [61], and Mexico [62] were more than that in Iran. While, the prevalence of infestation was lower in Korea [59], Australia [58], and another Turkish study [54] in comparison with the prevalence in Iran.

Table 4.

Prevalence of head lice in primary school in other countries.

| First author | Country | Publication y | Sample size | Prevalence (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Total | ||||

| Gazmuri [50] | Chile | 2014 | 467 | 23 | 55.2 | 40.3 |

| Abd El Raheem [51] | Egypt | 2015 | 10,935 | — | — | 16.7 |

| Karakuş [1] | Turkey | 2014 | 214 | — | — | 13.5 |

| Gulgun [52] | Turkey | 2013 | 8,122 | 0.9 | 25.2 | 13.1 |

| Değerli [53] | Turkey | 2013 | 342 | 1.1 | 13.7 | 10.2 |

| Değerli [54] | Turkey | 2012 | 772 | 0.2 | 12.9 | 6 |

| Çetinkaya [55] | Turkey | 2011 | 405 | — | — | 10.9 |

| Rassami [56] | Thailand | 2012 | 3,747 | 0 | 47.1 | 23.3 |

| AlBashtawy [57] | Jordan | 2012 | 1,550 | 19.6 | 34.7 | 26.6 |

| Currie [58] | Australia | 2010 | 702 | — | — | 5.3 |

| Oh [59] | Korea | 2010 | 15,373 | 1.9 | 6.5 | 4.1 |

| Toloza [60] | Argentina | 2009 | 1,856 | 26.7 | 36.1 | 29.7 |

| Bachok [61] | Malaysia | 2006 | 463 | — | — | 35 |

| Manrique-Saide [62] | Mexico | 2011 | 140 | — | — | 13.6 |

Among the above foreign studies, eight studies reported sex specific prevalence estimates. The prevalence among girls in Korea [59] was lower than that of the current study, while Chile [50], Turkey 52, 53, 54, Thailand [56], Jordan [57], and Argentina [60] reported more girls contaminated than in Iran. Iranian school boys were less affected than those in Chile [50], Jordan [57], and Argentina [60] and more than boys investigated in Turkey 52, 53, 54 and Thailand [56]. The prevalence of infestation In Iranian boy students was similar to those of Korean students [59].

Comparing the results of different countries with those in Iran showed that the rate of infestation among all Iranian students, as well as among girls, is lower than those in most other countries. Conversely, Iranian boy students were more infested than those in most other countries. Moreover, the reported prevalences in other countries varied greatly. These reports showed that although the infestation rate is distributed worldwide; it is not equal among different countries and seems to be associated with cultural and socioeconomic factors 55, 56, 57, 62. A limitation in this comparison is that the reported prevalence in Iran is based on meta-analytic results while the results of the other countries are according to primary studies. These comparisons could be different if the prevalences of the other countries were estimated with meta-analytic methods.

Risk of pediculosis is associated with different factors. Prevalence of infestation is more common in low socioeconomic regions, high density populations, where there is lack of personal hygiene, poor health facilities, and lack of a school health educator. This infestation also occurs when hair and clothes are not regularly washed. In addition, pediculosis is related to educational levels of parents and their attitude to health standards [63]. Our study showed that the frequency of head lice infestation among primary school children is related to different factors. In a study conducted among 2,210 Korean school students, similar to the current study, the infestation was significantly less common among students whose parents were teachers or employees and more common among those with less frequent hair washing per week. However, in contrast to the current study, the prevalence of infestation was contributed to a small family size and no association was observed between infestation and parents' education [64], while more educated Iranian parents increased the risk of pediculosis according to our meta-analysis.

In Egypt [51], primary school girls, in comparison with school boys, were 25.8% more infested and family size and access to enough water supplies were associated with pediculosis infestation. These findings are in accord with the current situation in Iran. Turkish school girls were 3.1 fold more contaminated than boys [1], while this ratio was higher for Iranian students.

In the other study carried out in Turkey [52], female sex, living with three or more siblings, and low educational levels of mothers and fathers, increased the risk of infestation approximately 41 folds, two folds, 73% and 45%, respectively. Such findings are in agreement with the current study.

According to a third Turkish school survey, head lice infestation prevalence was more common among students with a previous personal and family history of infestation. However, frequency of bathing and hair washing, shared use of a comb, towel and bed, family size, and also the number of family members per room had no influence on pediculosis infestation prevalence. Similar to our findings, the rate of infestation among Turkish students with long hair were more than three times higher than those of students with short hair [53].

Çetinkaya et al [55], in a study performed in Turkey, found no association between infestation with parents' level of education, type of house, and lack of bathroom within the house. Based on a cross sectional study in Jordan in 2012 [57], infestation was significantly related to sex (34.7% in girls vs. 19.6% in boys), living in a village (31.2% in rural area vs. 23.5% in urban area), and past history of infestation (57.4% in those with a positive history vs. 11.5% in those without). It was also associated with small family size, low income, long hair, lack of a bathroom, and low frequency of hair washing. In addition, a cross sectional study in Mexico [62] introduced factors such as low income (odds ratio = 9.9) and low frequency of hair washing (odds ratio = 8) as risk factors for head lice infestation.

Comparison of the factors relating to pediculosis infestation demonstrated the common determinant factors were different among countries. Approximately all associated factors had socioeconomic, cultural, behavioral, and health backgrounds. Therefore, we can overcome this global health problem by reasonable planning. The majority of these factors are easily avoidable with minimum cost and simple actions such as keeping the hair neat and short, increase the frequency of hair washing per week, not sharing a personal comb and towel, and effective and prompt treatment of infested students. The main point in the prevention of reinfestation is establishing and maintaining appropriate health behaviors by comprehensive and continued supervision.

The current study represented a comprehensive understanding of pediculosis prevalence and its determinant factors among Iranian elementary school children. Since the results of this study have been estimated based on scientific and statistical procedures and were comprehensively compared with the results of other national and international studies, they can be reasonably used for policymaking.

Many investigated studies during the current systematic review and meta-analysis did not report any significance level (p value) of the associations. Therefore, we could not perform p value meta-analysis for the correlations between pediculosis and other relevant factors. Remarkable heterogeneity between primary studies was another limitation of this study. Therefore, we applied a random effect model to combine the primary results in this meta-analysis.

Our study revealed that there is a high prevalence of head lice infestation among Iranian primary school children, particularly girls. We also observed that parents' educational level and profession, shared use of personal hygiene items, hair length, family size, having a bathroom within the house, and frequency of bathing per week, can be considered as determinant factors of infestation among these students.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0) which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Karakuş M., Arıcı A., Toz So. Prevalence of head lice in two socio-economically different schools in the center of Izmir City, Turkey. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2014;38(1):32–36. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2014.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morsy T.A., el-Ela R.G., Mawla M.Y. The prevalence of lice infesting students of primary, preparatory and secondary schools in Cairo, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2001 Apr;31(1):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammed A.L. Head lice infestation in school children and related factors in Mafraq governorate, Jordan. Int J Dermatol. 2012 Feb;51(2):168–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazrati Tappeh K., Chavshin A.R., Mohammadzadeh Hajipirloo H. Pediculosis capitis among primary school children and related risk factors in Urmia, the main city of West Azerbaijan, Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2012 Jun;6(1):79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davarpanah M.A., Rasekhi Kazerouni A., Rahmati H. The prevalence of Pediculus capitis among the middle schoolchildren in Fars Province, southern Iran. Caspian J Intern Med. 2013 Dec;4(1):607–610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapeere H., Brochez L., Verhaeghe E. Efficacy of products to remove eggs of Pediculus humanus capitis (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) from the human hair. J Med Entomol. 2014 Mar;51(2):400–407. doi: 10.1603/me13106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamiabi F., Nakhaei F.H. Prevalence of pediculosis capitis and determination of risk factors in primary school children in Kerman. East Mediterr Health J. 2005 Sep–Nov;11(5–6):988–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zahirneia M., Taherkhani H., Bathaei J. Comparison assessment of three shampoo types in treatment of infestation of head lice in elementary school girl in Hamadan. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2005;49(9–11):16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buczek A., Markowska-Gosik D., Widomska D. Pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in Urban and rural areas of eastern Poland. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:491–495. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000027347.76908.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omidi A., Khodaveisi M., Moghimbeigi A. Pediculosis capitis and relevant factors in secondary school students of Hamadan, West of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2013 Sep;13(2):176–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motovali-Emami M., Aflatoonian M.R., Fekri A. Epidemiological aspects of Pediculosis capitis and treatment evaluation in primary-school children in Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008 Jan;11(2):260–264. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.260.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vahabi A., Shemshad K., Sayyadi M. Prevalence and risk factors of Pediculus (humanus) capitis (Anoplura: Pediculidae), in primary schools in Sanandaj City, Kurdistan Province, Iran. Trop Biomed. 2012 Jun;29(2):207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moosazadeh M., Nekoei-Moghadam M., Emrani Z. Prevalence of unwanted pregnancy in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014 Jul–Sep;29(3):e277–e290. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elm E.V., Altman D.G., Egger M., STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007 Oct;335(7624):806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammadi-Azni S. Prevalence of head lice at the primary schools in Damghan. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2014 Nov;16(11):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moradi A.R., Zahirnia A.H., Alipour A.M. The prevalence of Pediculosis capitis in primary school students in Bahar, Hamadan province, Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2009 Jun;9(1):45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motevalli Haghi F., Golchin M., Yousefi M. Prevalence of Pediculosis and associated risk factors in the girls primary school in Azadshahr City, Golestan Province, 2012–2013. Iran J Health Sci. 2014 Jun;2(2):63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazari M., Saidijam M. Pediculus capitis infestation according to sex and social factors in Hamedan-Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007 Oct;10(19):3473–3475. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.3473.3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salehi Sh, Ban M., Motaghi M. A study of head lice infestation (Pediculosis capitis) among primary school students in the villages of Abadan in 2012. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2014 Jul;2(3):196–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alempour-Salemi J., Shayeghi N., Zeraati H. Some aspects of head lice infestation in Iranshahr area (southeast of Iran) Iran J Public Health. 2003;32:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayyadi M., Vahabi A., Sayyad S. An epidemiological survey of head louse infestation among primary school children in rural areas of Ravansar County, West of Iran. Life Sci J. 2013 Jan;10(12s):869–872. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shayeghi M., Paksa A., Salim Abadi Y. Epidemiology of head lice infestation in primary school pupils, in Khajeh city, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2010 Jun;4(1):42–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soleimani M., Zare S., Hanafi-Bojd A.A. The epidemiological aspect of Pediculusis in primary school of Qeshm, South of Iran. J Med Sci. 2007;7(2):299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vahabi B., Vahabi A., Gharib A. Prevalence of head louse infestations and factors affecting the rate of infestation among primary schoolchildren in Paveh City, Kermanshah Province, Iran in the years 2009 to 2010. Life Sci J. 2013 Jan;10(12s):360–364. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yousefi S., Shamsipoor F., Salim Abadi Y. Epidemiological study of head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) infestation among primary school students in rural areas of Sirjan County, South of Iran. Thrita J Med Sci. 2012 Jun;1(2):53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afshari A., Gholami M., Hagh-Verdi T. Study of prevalence of head lice infestation in female students in primary schools in Robat Karim County during 2008–2009 years. J Toloo-e-behdasht. 2013;12(2):102–111. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arjomanzadeh S., Tahmasebi R., Jokar M. Prevalence of pediculosis and scabies in primary school in Bushehr city. J South Med. 2001;1:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bashiribod H., Eslami G., Fallah F. Prevalence of head lice primary schools in Shahryar and lice-killing effects on pollution. Pajoohandeh J. 2001;6(4):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davari B., Yaghmaie R. Prevalence of head lice and its related factors in the primary school students in Sanandaj 1999. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2005;10(1):39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doroodgar A., Sadr F., Sayyah M. Prevalence and associated factors of head lice infestation among primary schoolchildren in city of Aran and Bidgol (Esfahan Province, Iran), 2008. Payesh J. 2011 Oct;10(4):439–447. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farzinnia B., Hanafi Bojd A., Reis Karami S. Epidemiology of Pediculosis capitis in female primary school pupils Qom. Hormozgan Med J. 2004 May–Jul;8(2):103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghaderi R., Eizadpanah A., Miri M. The prevalence of Pediculosis capitis in school students in Birjand. Modern Care J. 2010 Jan;7(1–2):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gholami Parizad E., Abedzadah S. Studying headlice infestation and factors affecting it among the primary school students in lIam. JIUMS. 2001;8–9(29–30):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosseini S.H., Rajabzadeh R., Shoraka V. Prevalence of Pediculosis and its related factors among primary school students in Maneh-va Semelghan district. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2014 Feb–Apr;6(1):50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Javidi Z., Mashayekhi V., Maleki M. Prevalence of Pediculosis capitis in primary school girls in Mashhad City. Med J Mashhad. 2004;47(85):281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Modarresi M., Mansoori Ghiasi M., Modarresi M. The prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children in Tonekabon, Iran. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2013;18(60):41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moradi A.R., Bathaii S.J., Shojaeian M. Outbreak of Pediculosis capitis in students of Bahar in Hamedan province. J Dermatol Cosmet. 2012 Jul;3(1):26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motalebi M., Minoueian Haghighi M.H. The survey of Pediculosis prevalence on Gonabad primary school students. Ofogh-e-Danesh. 2000;6(1):80–87. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motavalli-Emami M., Shams M., Sadri G. A survey to determine the prevalence of Pediculosis in students of Khomeini-Shahr district in the school year of 2000–2001. J Isfahan Univ Med Sci. 2003;8(4):102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motevalli-Haghi S.F., Rafinejad J., Hosseni M. Prevalence of Pediculosis and associated risk factors in primary-school children of Mazandaran Province, Iran, 2012–2013. J Mazand Univ Med Sci. 2014;23(110):82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noroozi M., Saghafipour A., Akbari A. The prevalence of Pediculosis capitis and its associated risk factors in primary schools of girls in rural district. J Shahrekord Uuniv Med Sci. 2013 May;15(2):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poorbaba R., Moshkbid-Haghighi M., Habibipoor R. Prevalence of Pediculosis capitis in primary school children at Guilan province in 2002–2003. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2004;13:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rafie A., Kasiri H., Mohammadi Z. Pediculosis capitis and its associated factors in girl primary school children in Ahvaz City in 2005–2006. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2009;45:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rafinejad J., Noorollahi A., Javadian A. Epidemiology of Pediculosis capitis and its related factors in primary school children in Amlash, Gilan province in 2003–2004. Iranian Epidemiol J. 2006;2(3–4):51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saghafipour A., Akbari A., Norouzi M. The epidemiology of Pediculus humanus capitis infestation and effective factors in elementary schools of Qom province girls 2010 Qom, Iran. J Qom Univ Med Sci. 2012;6(3):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shahraki G.H., Azizi K., Yousefi A. Head louse infestation rate of primary school students in Yasuj city. J Yasuj Univ Med Sci. 2001;6(21–22):22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soleimanizadeh L., Sharifi K. Study of effective factors on prevalence of head lice in primary school students of Bandar Abbas (1999) Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2002;7(19):79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yaghmaie R., Rad F., Ghaderi A. Prevalence of head lice infestation in girl primary school children in Sanandaj in 2004. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2006;12:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zabihi A., Jafarian Amiri S.R., Rezvani S.M. A study on prevalence of Pediculosis in the primary school students of Babol, 2003–2004. JBUMS. 2005;7(4):88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gazmuri B.P., Arriaza T.B., Castro S.F. Epidemiological study of Pediculosis in elementary schools of Arica, northern Chile. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2014 Jun;85(3):312–318. doi: 10.4067/S0370-41062014000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abd El Raheem T.A., El Sherbiny N.A., Elgameel A. Epidemiological comparative study of pediculosis capitis among primary school children in Fayoum and Minofiya governorates, Egypt. J Community Health. 2015 Aug;40(2):222–226. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gulgun M., Balci E., Karaoğlu A. Pediculosis capitis: prevalence and its associated factors in primary school children living in rural and urban areas in Kayseri, Turkey. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2013 Jun;21(2):104–108. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Değerli S., Malatyalı E., Mumcuoğlu K.Y. Head lice prevalence and associated factors in two boarding schools in Sivas. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2013;37(1):32–35. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2013.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Değerli S., Malatyali E., Çeliksöz A. The prevalence of Pediculus humanus capitis and the coexistence of intestinal parasites in young children in boarding schools in Sivas, Turkey. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Jul–Aug;29(4):426–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Çetinkaya Ü., Hamamcı B., Delice S. The prevalence of Pediculus humanus capitis in two primary schools of Hacılar, Kayseri. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2011;35(3):151–153. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2011.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rassami W., Soonwera M. Epidemiology of Pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in the eastern area of Bangkok, Thailand. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012 Nov;2(11):901–904. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.AlBashtawy M., Hasna F. Pediculosis capitis among primary-school children in Mafraq Governorate, Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2012 Jan;18(1):43–48. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Currie M.J., Reynolds G.J., Glasgow N.J. A pilot study of the use of oral ivermectin to treat head lice in primary school students in Australia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010 Nov–Dec;27(6):595–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oh J.M., Lee I.Y., Lee W.J. Prevalence of Pediculosis capitis among Korean children. Parasitol Res. 2010 Nov;107(6):1415–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toloza A., Vassena C., Gallardo A. Epidemiology of Pediculosis capitis in elementary schools of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Parasitol Res. 2009 Jun;104(6):1295–1298. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bachok N., Nordin R.B., Awang C.W. Prevalence and associated factors of head lice infestation among primary schoolchildren in Kelantan, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006 May;37(3):536–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manrique-Saide P., Pavía-Ruz N., Rodríguez-Buenfil J.C. Prevalence of Pediculosis capitis in children from rural school in Yucatan, Mexico. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2011 Nov–Dec;53(6):325–327. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652011000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva L., Aguiar Alencar R., Goulart Madeira N. Survey assessment of parental perceptions regarding head lice. Int J Dermatol. 2008 Mar;47(3):249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sim S., Lee W.J., Yu J.R. Risk factors associated with head louse infestation in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2011 Mar;49(1):95–98. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]